By Tony Barrell

Nuclear power stations now produce about 17% of the world’s electricity. In

The one country I know something about is a front line nuclear power –

Although in principle plans were devised in the 1950s, in 1973

Not Blessed by the Gods

The central government, led by METI, has for decades made it a matter of unquestionable logic that

Whatever its origins, in the decades since Japan was stripped of the empire, ‘not blessed by the gods’ has endured and recurred in many documents, which explain Japan’s energy/security problem. This is particularly the case since the late 1960s, Sometimes, it’s in a preface or preamble at the beginning of an official speech or paper to explain and justify whatever assertions follow, and has been repeatedly expressed in various versions of METI’s many instalments of Japan’s ‘Long Term Program’ for energy and in numerous expositions by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The World Energy Race

In recent years

Russian Greenpeace activists hold a banner reading,

“Stop the financing of Sakhalin oil” in June 2005, Moscow.

In all the current discussion about the realities, the prospects, the economics and the environmental impact of nuclear power generators, it’s easy to forget what a reactor is and does. It makes steam and irradiated spent fuel — plutonium — but because the fission process generates temperatures way in excess of the boiling point of water, a great deal of the engineering technology in a power reactor goes into its cooling system.

In the 1970s, a Fast Breeder Reactor (FBR) program, was proclaimed as a means by which Japan could break with the curse of the gods, and make for itself an everlasting supply of ‘indigenous’ fuel. By creating re-usable plutonium in a suite of FBRs Japan could, by burning this material in conventional reactors, become independent of uranium suppliers like

The Genpatsu at Work

I have visited a few genpatsu over the past decade or so, especially on the

Monju reactor was shut down in

1995 after a serious accident.

Corners had been cut in Monju’s construction and the company responsible (the Power Reactor & Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation —a corporatised government body widely known outside

Fukui’s reactor presence is around the coastline of the wide Wakasa Bay — famous all over the country for its many coves, inlets and beaches, oysters, a particular kind of ‘silky’ seaweed and sushi made from mackerel — which now has fifteen genpatsu in all (including Monju). In the centre of

Not many kilometres to the south is

On my visit to

Monju got its name from Monju Bosatsu, or Manjushiri, the bhodisattva who sits on Buddha’s left as the ‘protector of wisdom’. Monju is

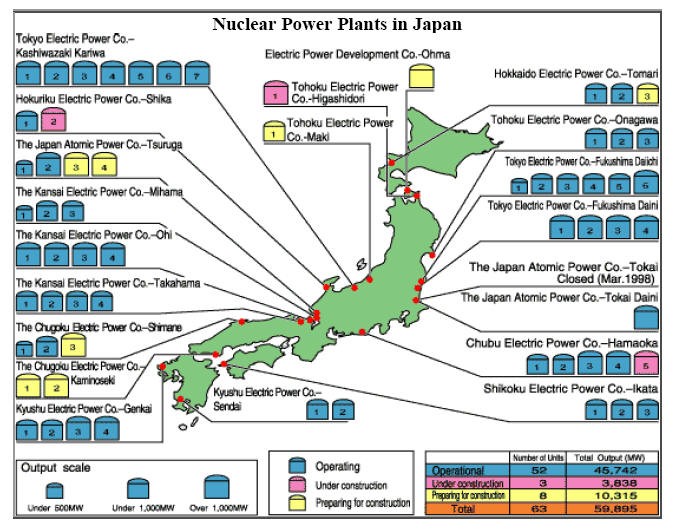

The great spurt of genpatsu-building in

The reason the industry has been tolerated, if not supported with enthusiasm, by many communities is because each nuclear installation has come with generous infrastructural sweeteners, paid for by the central government: schools, roads, bridges, sewerage systems, to persuade local prefectures, to say Yes. Comparatively poor regions, like remote

Saying No to Nuclear Power

However, some

In

On Christmas Eve 2003, the developer, the Tohoku Electric Power Company, abandoned its plans for Maki’s genpatsu. The same then happened at Suzu in the Ishikawa prefecture — on the

Any Japanese town or prefecture can organise a referendum against a development, a dam, a by-pass, even, in the case of Okinawa, an American base, and although the result doesn’t carry any weight in law, politicians are very wary of going against big No votes. Ever since 1999, when the Japanese government admitted it was wrong to use riot police to forcibly evict farmers for the expansion of

Anti-nuclear march in Japan, Aug. 2006.

Kakumihama is a wild spot. Even in summer there are only well wrapped walkers on the beach, but on a clear day, the Kashiwazaki cluster can be seen on the horizon to the south. This coast reminded me of the shores of

The Citizens Anti-Nuclear Movement

Mostly, people who have been opposing the building of new genpatsu over the past couple of decades are loosely described in Japan as ‘citizens groups’, local, one-issue coalitions that form alliances against dams, airports, chemical plants, genpatsu. Some are Green Party members, others are just single-minded individuals like Takashi Hirose who travelled the country, solo, addressing small meetings in school and community halls briefing ordinary people on safety and security issues. One of his main themes: if they are safe why not build them out in the open near big population centres, why hide them away on the

Jacket of Hirose Takashi‘s Tokyo ni

Genpatsu o (Bring the Nukes to Tokyo).

When writer, researcher, translator, Rick Tanaka, and well known Australian documentary film maker Tom Zubricky and I visited the far north eastern corner of the main island of Honshu in January 1989, meeting citizens groups for a film project, we inspected the site of what was to have been a huge ‘enterprise zone’ on the peninsula of Shimokita, one of Japan’s bleakest regions, in the far north east corner of Aomori prefecture. Around the hamlet of Rokkasho, a new town of factories was to have been built, but no commercial investors found this remote opportunity appealing, so the government decided it could be the ideal location for Japan’s nuclear industry to create a fuel-cycle complex: enrichment, reprocessing — Japan would re-process all its spent fuel (instead of sending it to France or Britain by sea) — the production of MOX (a mixture of uranium oxide and spent fuel already used in France, Germany, Belgium and Switzerland), high level waste storage and, planned for 2015, another FBR. The entire project was also the brainchild of METI’s Long Term Vision, and put under the tutelage of Japan Nuclear Fuel Limited, which is owned by the power utilities and the nuclear industry.

Way back when it was just a building site, we met local opponents — organic apple farmers, housewives, students —who hated the idea and we wandered around the vast expanse of frosted mud trying to imagine what the finished complex would look like. The only completed building was a well appointed visitors centre with audio-visual aids, brochures, posters, diagrams, and light boxes, much of the material aimed at school children and, as we browsed, a party of fifty or so ten year olds came by in a coach. Outside there was nothing but ice and snow and the occasional fighter-bomber from nearby Misawa US air base diving out of the clouds with a supersonic bang and then climbing vertically — just testing, or showing off. But things have moved on at Rokkasho: the enrichment plant has been working since 1992, the waste storage facilities have been completed, at a cost of US$ 20 billions the re-processing plant is supposed to start working in 2007 and the MOX mixing plant by 2009.

The plan is that enough of

As with other countries, few of

Growing Demand for Power

Since I started visiting

On the grander, national scale the great user is the train system, urban, suburban and national. Bullet trains use a lot of grid power, but they may eventually be joined by the ultra high speed magnetic levitation train (travelling at 500 kph) now in its R&D phase along a slow-speed version serving nine stations in Aichi prefecture. It’s been calculated by critics (and denied by its promoters) that to run this kind of very, very fast train successfully between Tokyo and Osaka (costing $82 billion to build) a Maglev system might require two or three dedicated nuclear power generators to provide its current.

The Japanese government will have its work cut out for it trying to prove that the Rokkasho complex is dedicated to the creation of ‘indigenous’ energy through ‘plutonium utilisation’, rather than proliferation, that all excess or ‘surplus’ plutonium will be reprocessed. All in all, the government says that Rokkasho can, and will, reprocess 800 tons of spent fuel in a year — the combined output of all nine regional power utilities — and that this will then be blended with MOX and then disposed of completely in reactors around the country. If all works according to METI’s plan, there will be no stockpile for use in nuclear weapons. It will all go up in smoke in genpatsu.

But while government and industry say all Japan’s surplus plutonium (it already has 40 tons) will gradually disappear, critics say even MOX can become weapons-grade material, and around the remote prefectures that host those 55 genpatsu, there are doubts that they can all be adapted to burn MOX, so even the plutonium already in existence may not disappear. The nine power utilities are not all committed to MOX, and several prefectures don’t want it moving through their narrow roads and lanes to reactors on the coast. These doubts and niggles have been there ever since the plan was first announced, years before I trudged around the Rokkasho site in the winter of 1989. Now, says Greenpeace, that reprocessing plant that goes into action next year is, like most nuclear fission planning, ‘a relic’ of 1950s thinking.

Japan’s Quest for Nuclear Weapons

So, the elephant in the tatami room is, of course, nuclear weapons, or at least the capability and capacity that the exponential generation of spent fuel, and its re-processing might enable, if Japan were to make the political decision to become a true nuclear power — closer now than it has been at any time since the Nakasone era of the mid-1980s. Not everyone believes

On the Japan side, the more nationalist politicians have consistently played up the North Korean menace, the more likely their constituents might be to accept the abandonment of the antique but enduring ‘three non-nuclear principles’, first declared by prime minister Sato in 1967, when he decided

It isn’t just

South Korean protesters shout slogans at an

anti-Japan rally in front of the Japanese embassy

in Seoul June 17, 2005. Dozens of civic leaders

demanded that Japan’s Prime Minister Koizumi

Junichiro stop visiting Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo.

I remember first visiting

In those days there was not much obvious waste. Old men would slowly wander around Tokyo neighbourhoods collecting swathes of cardboard piled on to trolleys for recycling, and the only things people threw away were perfectly usable but outmoded TV sets, sound systems and fax machines, neatly arranged next to their pot plants on the pavement.

Traditional attitudes (pre-war if you like) were imbued with the habit of abstemious re-use: recycling paper, glass, everything, was a normal household activity for centuries. Only two Japanese generations have grown up to be unconscious consumers who expect power to be available at the flick of a switch. Despite the collapse of the property bubble and the comparative stagnation of the 1990s, the Japanese became eager consumers and waste-makers; so we now read in the Australian Financial Review that the recent revival in the Japanese economy is mostly due to a significant rise in domestic consumption, and for the USA, China is maligned for dumping cheap exports on the world market.

In

Tony Barrell is a British-born Australian writer and broadcaster who now lives in

Posted at

[1] Figures in this essay come from the Uranium Information Centre, Japan Nuclear Fuels Ltd, and Citizens Nuclear Information Centre.