Tong Kim

Since President Lee Myung-bak took office, virtually all official channels of inter-Korean dialogue have been shut down, and it seems that the strained relations between Seoul and Pyongyang are likely to continue for an indefinite period of time. If confrontation replaces dialogue, it would further ratchet up the tension on the Korean Peninsula.

Only a few days after the Seoul government welcomed Washington’s de-listing of North Korea as a terrorist sponsor, Pyongyang issued a renewed warning that it may cut off all ties with the South, unless Seoul withdraws its “hostile policy” toward the North. The warning appeared in an article published by Rodong Shingmun, the DPRK’s Workers’ Party organ, on October 16. The article was full of slander and threats against the Lee administration.

The latest warning came two weeks after a working level inter-Korean military meeting at Panmunjom, in which the North protested balloon drops of propaganda leaflets by a civic group of the South. The North also threatened that if the leaflet dissemination did not halt, it might deny South Korean civilians’ access to the Gaesung Industrial Complex and the Mt. Geumgang resort.

During the days of progressive government in Seoul, there were no leaflet operations targeting the other side of the DMZ, and both sides suspended loud speaker broadcasts designed to demoralize their opponents over the fence. On a higher level, the two Korean authorities agreed to end mutual slander as a necessary step for rapprochement.

According to South Korean press, the leaflets informed North Koreans among other things of the stories regarding the North Korean leader’s troubled health and a doomsday forecast of the Kim Jong-il regime. The North Koreans have always vehemently reacted to any criticism or negative statement of Kim Jong-il. I learned that “no negative mention of the great general” was one of the preliminary preconditions for the first inter-Korean summit.

The Rodong Shinmun’s article said: “Tarnishing our supreme dignity is tantamount to an outright challenge to our system and a declaration of war.” Although this part was not mentioned in the KCNA’s shortened English version, “our supreme dignity” referred to Kim Jong-il himself.

There have been plenty of sources of displeasure to North Korea. Recent talk in the South of Kim Jong-il’s ill health and of a “sudden collapse” of his system, on top of the Lee administration’s tougher policy on the North, is believed to have been the direct cause of Pyongyang’s decision to shun the South and deal only with the United States. The Seoul government’s reported consideration of full participation in the U.S. led Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI) and building a missile defense shield against the North, as well as allowing the talk of a joint U.S.-ROK contingency plan to cope with “a sudden change” in the North upgrading Concept Plan 5029 to Operational Plan 5029 were all touching the nerve of the DPRK leadership.

To Seoul’s dismay, Pyongyang’s harsh rhetoric comes at a time when the DPRK’s relations with the United States seem to be moving forward – by the DPRK’s resumption of nuclear disablement and the likelihood of holding another round of the six-party talks, as well as the growing prospect of Barack Obama becoming the U.S. President, who said he would meet with Kim Jong-il.

The Ministry of Unification immediately tried to play down the significance of Rodong’s provocative threat based on the plausible assumption that the party organ does not necessarily represent the official position of the DPRK government and the North Korean leadership. It is true that the Rodong Shinmun’s priority is to keep the people in unity for loyalty to their leader and system, and it also serves as a tool to try out some policy ideas yet to be approved by the leadership.

But it should be heeded that the same paper had published its first harsh attack on the South in April this year, accusing the Lee administration of pursuing a “confrontation policy from traitorous anti-DPRK sycophancy.”

From all available indications, it is clear that the North does not want to talk to the South, unless the conservative South Korean government accepts the two summit agreements of June 15, 2000 and October 4, 2007. The Rodong article alleged that “the negation” of the two agreements “means denying the ideology and system in the DPRK and seeking confrontation.”

In retrospect, the South should have been more careful in its own rhetoric if it wanted to address the issues of concern through dialogue. After President Lee was elected, the North Koreans had tried to work with his new conservative government, by seeking a meeting with Lee’s people to discuss continued inter-Korean cooperation. They even offered to send a senior DPRK representative to attend President Lee’s inauguration ceremony. The North Korean offers were rejected.

Instead, Lee sent his envoys to Washington, Tokyo, Beijing and Russia to provide them with a preview of what his foreign policy would be like. He sent nobody to Pyongyang. Lee made it no secret that he would be tougher on the North than his two predecessors.

There are a number of instances that Seoul could have avoided if it wanted to prevent the precipitation of decline in its relations with Pyongyang. The first sign of trouble began with the unification minister’s statement in March that the new government would not expand the Gaeseong Industrial Complex at the absence of progress in denuclearization, which led to the immediate expulsion of South Korean officials from the complex.

On the same day, President Lee said his government would not engage the North against the will of the South Korean people, sending a message to Pyongyang that the people in the South did not want him to continue an engagement policy.

The ROK JCS chairman’s March statement that the South Korean military should first locate the sites of North Korean nuclear weapons and “strike them before the enemy uses them,” caused the North Korean military’s demand for apology from Seoul the next day, implicitly threatening to suspend inter-Korean dialogue and contacts.

Neither joint U.S.-ROK pressure on the North Korean human rights issue nor Seoul’s attempt to force an investigation of the incident of a South Korean woman shot to death at Mt. Geumgang through international pressure at the ASEAN Regional Form in July and Lee’s meeting with Bush in August – was helpful to resumption of inter-Korean dialogue.

Since President Lee took office, Pyongyang has been getting mixed signals from Seoul between engagement and confrontation, as it did from the Bush administration during its first six years – between negotiation and regime change. Lee has said more than once that he would be interested in meeting with Kim Jong-il for “genuine dialogue.”

Even during his visit to Washington last April, Lee told The Washington Post that he would propose an exchange of liaison offices between Seoul and Pyongyang as a permanent dialogue channel. On the same visit he told CNN that he wants to cooperate with Kim Jong-il – who Lee said could make a big decision — for “real peace and prosperity.” Pyongyang dismissed Lee’s proposal.

A day earlier he told a Korean American youth group in New York that there would be no talks with the North because it was waging a campaign of insults and bellicose statements against the South.

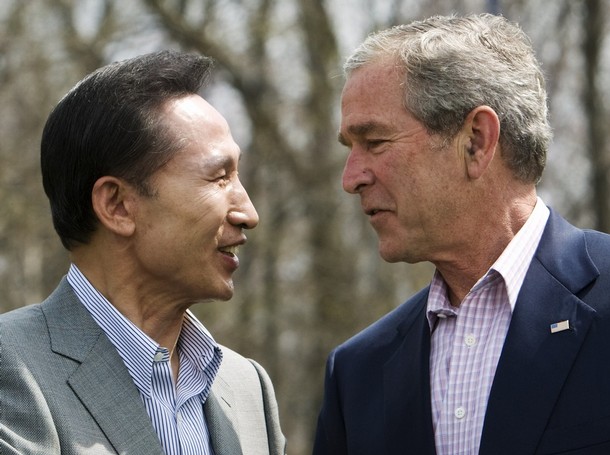

At the joint press availability with President Bush at Camp David, President Lee returned to his hard line stance on the nuclear issue, but said that he would still be willing to meet with the North Korean leader if such a meeting would “yield substantial and real results.” This might have been interpreted by Pyongyang as another way of saying that there is no real need for another summit.

In July, Lee told the National Assembly that with his priority on denuclearization, he would take “the road of coexistence and co-prosperity” that will benefit both the North and the South. At the beginning of the joint annual U.S.-ROK military exercise in August he said, “unification may come all of sudden,” an allusion to a sudden opportunity for absorption.

Then, during Bush’s visit to Seoul in August, Lee said that denuclearization should move in parallel with substantive cooperation between the two Koreas. Seoul still sticks to the policy of “denuclearization and opening 3000,” – which has long been rejected by the North. But the North should heed the shifting of that policy from “denuclearization first” to flexible response to progress in denuclearization.

Nobody can predict the timing or the likelihood of a demise of North Korea. That’s why it is important to resume dialogue and avoid a costly consequence – political, economic and military – from confrontation.

Tong Kim is Research Professor with the Ilmin Institute of International Relations at Korea University and an adjunct professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. He retired from the U.S. Department of State as the senior Korean language interpreter in June 2005 after 27 years of service, during which he interpreted for four American presidents – Reagan, Bush, Clinton, and W. Bush. He also interpreted for Secretary of State Albright’s meeting with North Korean leader Kim Jong Il in 2000.

This article appeared at the Northeast Asia Peace and Security Network Policy Forum Online on November 4, 2008. It is posted at Japan Focus on November 5, 2008.