Who is Korean? Migration, Immigration, and the Challenge of Multiculturalism in Homogeneous Societies

Timothy Lim

What is a Korean?

“I don’t know,” opines a 31-year old Korean woman. “I have always believed that Korea is a single-race country. And I’m proud of that. Somehow, Korea becoming a multiracial society doesn’t sound right.”[1] This is not an unusual view. Indeed, the large majority of Koreans would likely agree that Korean society is inextricably tied to and defined by a unique Korean identity, one based on an uncompromising conflation of race and ethnicity.[2] The strong tendency among Koreans to conflate race and ethnicity has important implications, the most salient of which is this: it has served to create an exceptionally rigid and narrow conceptualization of national identity and belongingness. To be “truly” Korean, one must not only have Korean blood, but must also embody the values, the mores, and the mind-set of Korean society. This helps explain why overseas Koreans (from China, Russia, Japan, the United States and other countries throughout the world[3]) have not fit into Korean society as Koreans. They are different, “real” Koreans recognize, despite sharing the same blood. At the same time, those who lack a “pure blood” relationship, no matter how acculturated they may be, have also been rejected as outsiders. This rejection, more importantly, has generally led to severe forms of discrimination.

This is arguably most apparent with “Amerasians,” who, in South Korea, are primarily children born to a Korean woman and an American man, usually a U.S. soldier.[4] It is important to note here that it was only in 1998 that non-Korean husbands gained legal rights to naturalize, while non-Korean wives have long had this right. At the same time, up until 1994, most “international marriages” in Korea were between a foreign man and Korean woman. According to the ethno-racial and patrilineal logic of belongingness in South Korea, then, Amerasians have been viewed as decidedly non-Korean interlopers who belong, if anywhere, in the land of their fathers. The ill treatment of Amerasians was, as Mary Lee and others have argued, exacerbated by a patriarchal and hyper-masculine sense of national identity: Amerasian children were associated with the “shame” and “humiliation” of a dominant Western power conquering and abusing Korean women for sexual pleasure.[5] Not surprisingly, then, Amerasians have been ostracized from mainstream Korean society; they were not only subject to intense and pervasive interpersonal and social abuse,[6] but also to institutional discrimination—Amerasian males, for example, were barred from serving in the South Korean military, which is mandatory for every other Korean male and is “an institutional rite of passage which enables access to citizen rights” (emphasis added)[7] (This law was revised in 2006 so that “mixed-blood” Koreans could voluntarily enlist for military service.) In concrete terms, the discriminatory treatment of Amerasians has resulted in unusually high school drop out rates (and much lower levels of educational achievement overall),[8] significantly higher rates of unemployment and underemployment, and much lower pay.[9]

Given the mistreatment of Amerasians in Korean society, it is not at all surprising that other “out-groups” would have experienced similar treatment. But, until fairly recently, there were few other significant out-groups in South Korea. This is no longer true: for, over the last two decades, hundreds of thousands of newcomers or foreign migrants have flowed into South Korea from other parts of Asia and around the world. The first large groups of foreign migrants—almost exclusively non-skilled workers—were subject to intense exploitation and abuse: they were treated as little more than cheap, expendable commodities by the Korean factory owners and small-scale business people for which they worked. (Not surprisingly, Amerasians have been largely relegated to the same type of work.) The South Korean government, moreover, played a key role in making this possible, first, by helping to criminalize foreign workers—despite the obvious need and demand for their labor—such that most became “illegal immigrants” (this was the case for most of the 1990s);[10] and, second, by working to legitimize, through an “Industrial Technical Training Program” (which ran from the early 1990s to 2004), a highly discriminatory labor system that sought to institutionalize low wages and limited worker protections: the “trick” was to define full-fledged (foreign) workers as mere trainees (the Korean system, it is useful to note, was modeled after a similar system in Japan).[11] Significantly, even those foreign workers who shared Korean blood—i.e., ethnic Koreans from China or Josenojok—were subject to the same abuses and mistreatment. Over the years, conditions for foreign workers have improved markedly (a process I discuss in detail elsewhere[12]), but the social basis for discrimination has remained largely intact, namely, an extremely narrow conceptualization of Koreanness that determines who is, and who is not, classified as Korean.

A protest organized by the Migrants Trade Union (MTU), an organization of foreign workers in South Korea, February 18, 2009 (Source: Photograph taken by author)

By itself, I should emphasize, a deeply embedded sense of Koreanness is not a bad thing. All (modern) societies are based on a common or shared identity. The source of this identity may be a notion of shared blood (i.e., race), ethnicity or both, as it is in contemporary Korea (and Japan). But a shared commitment to a political or social idea can also bind members of a national community together. Most national communities are, by their very nature, too large and dispersed for most members to ever meet or directly interact with all but the tiniest fraction of the community. In this sense, all national communities are, in the now well-worn phrase by Benedict Anderson,[13] “imagined” in that they are bound together by abstractions rather than physical connections. To put it in slightly different terms, national communities are formed from reified, collective myths that define the boundaries of belongingness. Such collective myths help to create and sustain national unity and purpose. For Korea, the collective mythology played a particularly important role in the resistance against Japan’s “assimilation policy” during the early part of the 20th century and (for South Korea) in the turbulent “transition to modernity” in the post-liberation years.[14]

By contrast, it is easy to see what can happen in societies in which a national community—bound together by a shared identity—is weak or nonexistent. The ethnic and separatist violence that racked the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s is testament to this. An even more salient example is Iraq today: although the country suffers from many problems, one of the most serious is the lack of a shared identity. There is, to put it simply, no overarching “Iraqi” identity as such, only competing identities—Shiite, Sunni, Kurdish, Arab, Islamist, and so on—distinguished largely, albeit not solely, on the basis of ethnicity.[15] Of course, the fragmentation of identity in Iraq today is itself the product of a complex and highly contingent political process, one that is well beyond the scope of this paper to address. Suffice it to say, however, that just as there was a strong national consciousness in the past, a unified Iraqi identity may emerge in the future.

Still, identities based on a notion of ethnic and/or racial homogeneity can be dysfunctional and even dangerous, especially in societies undergoing significant and rapid social change. The reason is clear: they create an extremely narrow and rigid category of belongingness that may marginalize and subordinate certain groups of people, or even entire communities that do not meet the criteria for “membership.” Such subordination, at the very least, undermines human rights and legitimates and institutionalizes discriminatory treatment of out-groups—as has certainly been the case in South Korea. More seriously, the marginalization and subordination of certain groups based, even if only in part, on an ascribed identity of “otherness” is frequently expressed as xenophobia, and may lead to widespread social and political conflict. Such was the case in France when “ethnic riots” engulfed the working-class suburbs around Paris in 2005 and after. More recently in 2008, murderous violence was inflicted on foreign immigrants in South Africa. In the United States, violence against out-groups has been less dramatic in recent times, but immigrants have long been subject to scapegoating and “racial hatred.”

At present, the exclusionary nature of national identity in South Korea has not been a source of widespread social tension or conflict, still less ethnically based communal violence. Korea has been fortunate in this regard if only because out-groups in Korean society have, until recently, been very small. But this is changing, as I will discuss in the following section. One basic objective of this article, in fact, is to describe and analyze the inexorable demographic changes that are taking place in South Korea. At the same time, this paper is designed to show that these changes are creating significant challenges for South Korea, specifically with regard to the country’s hitherto exclusionary national identity. Establishing that South Korea will face significant demographic and social challenges in the future, however, is not the sole or even principal goal of this paper. I am also concerned with assessing the prospects for change in South Korea. In particular, I am concerned with the question: “Can South Korea make the shift from a self-defined “mono-racial” and “mono-ethnic” society to a multicultural or multiethnic one?” While I do not offer a definitive answer, I argue that a fundamental shift is not only imaginable, but also distinctly possible.

To support my argument I draw from an unlikely comparative case: Australia. Among the reasons for making this comparison is that Australia’s national identity was once every bit as narrowly defined and restrictive as South Korea’s. Indeed, there is a strikingly similar parallel between the social construction of a mono-racial and mono-ethnic national identity in the two countries. In considering the utility and validity of a comparison between Australia and South Korea, moreover, it is important to avoid the fallacious assumption that two otherwise very different units of analysis cannot be meaningfully compared. As students of comparative politics understand, “most different systems” are comparable, particularly when the key variables of interest are the same or similar between the two units of analysis.[16] In this regard, too, I believe that a comparative analysis of Australia and South Korea holds some lessons for Japan. In this case, though, it is the hard-to-miss parallels between South Korea and Japan that will likely draw the most attention: recognizing this, I try to highlight some of the most salient similarities. This paper, however, is not meant to provide a systematic comparison, so my comparisons here will be far more suggestive than substantive.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: in the next section, I describe (in summary fashion) some of the major demographic changes that have been taking place in Korea over the last two decades; I also show that the “demographic shift” in Korea is a long-term trend and one that is more likely to accelerate than to reverse course. Second, I examine the social implications of increasing diversity within South Korean society. I suggest, in the following section, that the most viable route toward a “multi-ethnic” society in Korea should be based on developing a more inclusive definition of who belongs to Korean society. This leads to my final substantive section, a discussion of Australia’s turn toward multiculturalism and the implications for South Korea. To repeat, the primary objective of this section is to demonstrate the real-world possibility of large-scale change from a racially and ethnically based conception of national belongingness toward a more inclusive “multi-cultural” one.

The End of the Homogenous Nation: The Demographic Shift in Korea

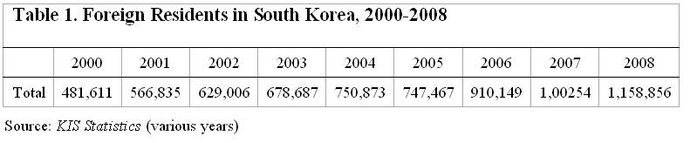

South Korea is experiencing a significant demographic transition: in the space of less than two decades, from 1990 to 2007, the number of “foreign residents”[17] in South Korea grew from just under 50,000 to over one million (equivalent to 2 percent of South Korea’s population). This represents a 2,000 percent increase over 18 years. The one million-person milestone, according to the Ministry of Justice, was first reached in August 2007;[18] by the end of 2008, this number had already grown to 1,158,866 (2.35 percent of the total population).

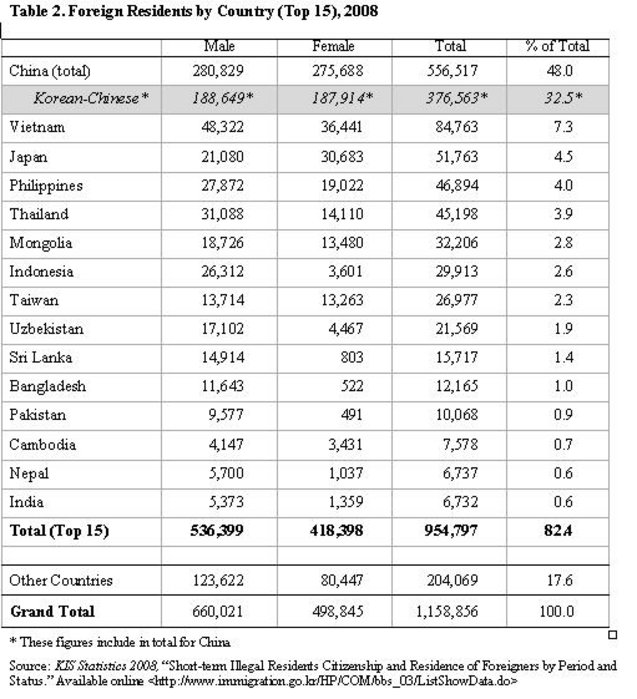

The largest numbers of foreign residents, about 377,000 (or 32.5 percent), are ethnic Koreans from China (Joseonjok), but as indicated above, migrants come from around the world. The largest groups are from China (other than Joseonjok), Vietnam, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Mongolia, Indonesia, Taiwan, Uzbekistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Cambodia, Nepal and India.

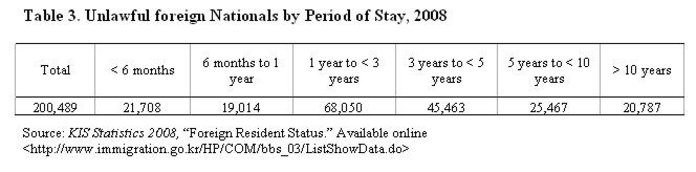

Most foreign residents (more than 70 percent[19]) are non-skilled workers, and many of these workers are in South Korea illegally. Moreover, while non-skilled foreign migrant workers are, by law, temporary residents, many have lived and worked in Korea for more than five years and some for longer than two decades: according to the Korean Immigration Service, of the 200,489 “unlawful foreign nationals” in Korea in 2008, more than 46,000 had been living in the county for five years or longer and, of these, almost 21,000 had been in South Korea for at least 10 years.

There are, I should also note, a growing number of skilled or professional workers: between 1990 and 2006, the number has increased from 2,833 to 27,221 (even the larger figure, however, represents only 6.4 percent of all registered migrant workers in South Korea for that year).[20]

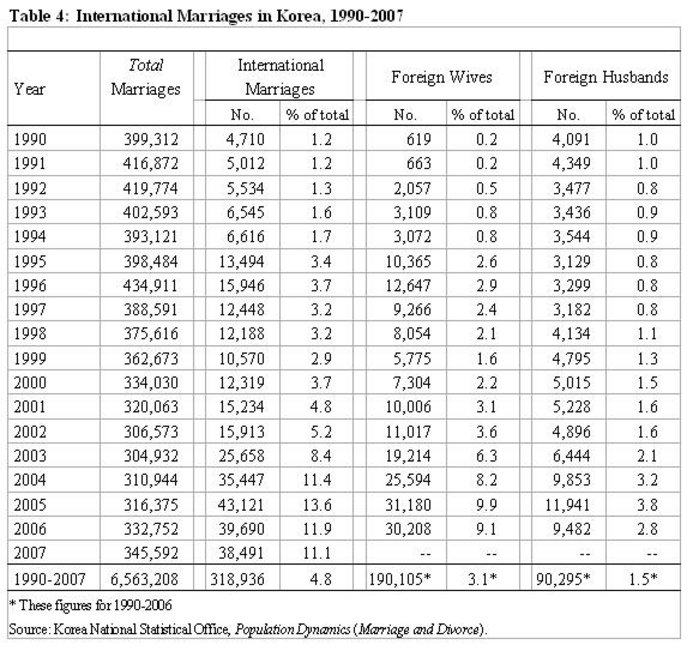

Another increasingly important source of diversity comes from the dramatic increase in international marriages. As recently as 1990, there were only 619 international marriages in total. Between1990 and 1999, however, the numbers began to ramp up, reaching a cumulative total 93,063 or an average of about 9,300 per year. By the early 2000s, international or “multicultural marriages” (as they are now often called) had started to take off. In 2001, the number was 15,234 and by 2005 (the peak year), there were 43,121 international marriages in the country, which accounted for 13.6 percent—about one in seven—of all marriages in Korea that year.[21]

As of December 2007, the total number of immigrants to South Korea through marriage stood at 146,508 (of this number, 30 percent or 44,291 have obtained Korean nationality[22]). Most international marriages involve foreign brides, and most foreign brides are from China, many of them being Joseonjok. At the same time, there are also a large number of women who come from Vietnam and the Philippines to marry Korean men.

The substantial increase in international marriages, it is important to note, does not reflect a newfound openness to foreign cultures. Instead, particularly the increase in the number of “migrant brides” is a product of a number of intersecting factors, the most salient being demographic. There is a shortage of “marriageable women” for certain groups of Korean men—specifically, for never-married men in rural areas and previously married (divorced or widowed) or disabled men of “low socio-economic status” in urban areas. In Korea’s rural areas, the lack of marriageable women is particularly acute, as many rural women marry into urban families or simply leave rural areas. The statistics are telling: in rural villages (myun), for ages 20-24, the sex ratios (number of males to females) were 1.26, 1.51, 1.88, and 1.62 in 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 respectively.[23] As a result of this imbalance, in 2007, international marriages accounted for 40 percent of all marriages among men engaged in agriculture.[24] The economic gap between South Korea and the major sources of “migrant brides” is another salient factor. This gap reflects a more generalized phenomenon—also referred to as global hypergamy[25]—in which women from poorer countries (such as Vietnam, the Philippines, China, and other countries in South and Southeast Asia) move to economically wealthier countries as “marriage migrants”[26]; Korea has joined Japan and Taiwan as such a site for international marriage. There are a number of other critically important factors as well, including the role of the Korean state, the Unification Church (which has played a key role in arranging marriages between Korean men and women from the Philippines[27]), and commercial agencies (e.g., marriage brokers and international “matchmaking” agencies).[28]

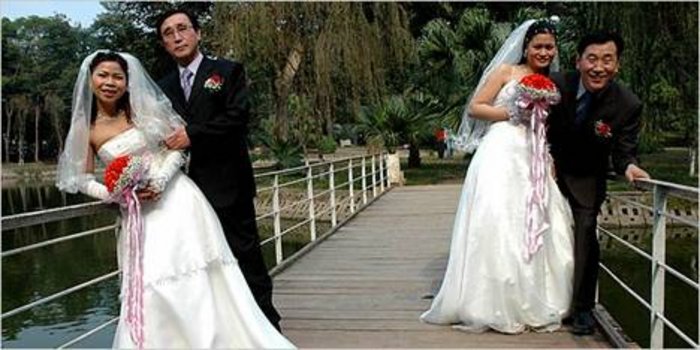

From left, Bui Thi Thuy and Kim Tae-goo and To Thi Vien and Kim Wan-su prepared for weddings in Vietnam and life in South Korea, February 2007 (Source: Người Việt Ly Hương)

There is, finally, an “endogenous” source of diversity: the children of international marriages. As the number of international marriages has increased, so too has the number of “multicultural children.” Amerasians, as I noted above, has been part of South Korea since the 1950s, but their numbers have always been relatively small due, in part, to overseas adoptions (and, of course, some emigrate to the United States with their American fathers).[29]

A membership meeting of Korean Amerasians, held in Fullerton, CA, May 24, 2009 (Source: Korean Amerasians Association)

Over the past 20 years, moreover, their numbers have been greatly overshadowed by the growing number of “Koasians” (part Korean, part “Asian”). According to the Korean Immigration Service, in mid-2008, there were at least 51,918 “multicultural children” in South Korea including Amerasians and Koasians). Of these, 33,140 were age six or younger, and 18,778 were school age, the number of is the latter rising rapidly from 7,988 in 2006 to 18,445 in 2008. These figures do not include the children of undocumented workers, many of whom are married to compatriots and not to Korean spouses, but are reluctant to register their children with local schools for fear of being deported or imprisoned. There are an estimated 5,845 such children.[30] (Korean law allows any child between the age of seven and 12, regardless of residency or legal status, to register with a local elementary school.)

These trends—both international marriages and international worker migration flows—remain strong and are likely to grow. The Korean government projects the proportion of foreign residents in Korea to increase to 5 percent by 2020.[31] Furthermore, given Korea’s low fertility rate of 1.08,[32] one of the lowest in the world, the 5 percent figure will almost certainly be little more than a waypoint in a much longer journey toward significant social heterogeneity. The reason is clear: Korea, along with Japan and other societies with low birthrates, simply will not have enough able-bodied people to replace their working age populations and support welfare systems for the growing numbers of retirees. A well-known UN study in 2001 indicated that Korea would need a total of 6.4 million immigrants between 2020 and 2050, or an average of 213,000 per year, to keep the size of its working age population (15-64 years old) constant at its then figure of 36.6 million.[33] Japan faces a comparable situation: the “medium variant projection” in the UN study indicated that, to keep “the size of its population at the level attained in the year 2005, the country would need 17 million net immigrants up to the year 2050, or an average of 381,000 immigrants per year between 2005 and 2050. By 2050, the immigrants and their descendants would total 22.5 million and comprise 17.7 per cent of the total population of the country.[34]

“Getting Ready For a Multi-Ethnic Society”?

Koreans are not blind to these changes and this is especially apparent in the media. From the most conservative to the most progressive news sources, editorial writers and columnists have acknowledged the country’s loss of homogeneity and its move toward a “multi-ethnic society.” Consider, for example, this editorial, written in 2005, from the Hankyoreh (one of Korea’s most progressive papers), “Get Ready for a Multi-Ethnic Society”:

Experts say that Korea is already no longer a homogeneous society, and that is has already essentially become an immigrant nation. As of last year foreign workers topped 420,000 and foreign wives numbered more than 50,000. Naturally there is a continuous rise in the number of children who have mothers or fathers from China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Mongolia, Russia, the US, and Japan. Given the fact Korea has a low birth rate and is aging and that international interaction is on the rise, the trend is going to accelerate. The problem is that our understanding of the situation and our society’s preparedness lags far behind that trend. Just as has been the case with foreign labor, marriage to foreigners has run into various problems …. It is time our country formulate real plans as a multi-ethnic society. To begin with, there needs to be better oversight of the international marriage agencies. Foreign spouses need to be given help in adjusting socially, through Korean language and cultural education. There needs to be counseling for the problems faced by international families. Most importantly we need to have open hearts that accept them as members of Korean society (emphasis added).[35]

According to the Hankyoreh editorial, “getting ready” for a multiethnic society primarily meant providing “better oversight of the international marriage agencies”, and giving foreign spouses more help in “adjusting socially, through Korean language and cultural education.” Tellingly, the latter suggestion ignores the notion that Korean husbands might be served by learning about their spouses’ culture and language. Also missing from the editorial is any discussion of how, for example, tens of thousands of “multicultural children” could be successfully integrated into South Korea’s educational system—an issue that, in 2005, was certainly salient. But, equally telling is the editorial’s exclusive focus on foreign spouses (even after pointing out that the large majority of foreign residents are workers): this reflected the then common assumption that foreign workers—especially non-skilled foreign workers—would and should have no permanent place in Korean society. There is, in short, little in the editorial—except for the very last sentence—that suggests “getting ready” would have necessitated any significant changes within Korean society and/or South Korea’s rigid ethno-racial conception of identity.

The failure of Hankyoreh to address the deeper significance of Korea’s transformation into a multi-ethnic society was typical of editorials and columns written before 2006. But that was before American football star, Hines Ward, won the 2006 Super Bowl Most Valuable Player (MVP) award. Mr. Ward happened to have a Korean mother and an African-American father. He had only lived in South Korea for one year after his birth. Still, after winning the MVP award, Mr. Ward became an overnight sensation in his “motherland.” The Korean national media embraced Ward as a Korean success story. Hundreds of stories were printed and aired about Ward and his Korean heritage and he began to appear frequently in advertisements in Korea. Ward received a “hero’s welcome” on his first visit to his “motherland” in April 2006. The tacit, if unintentional, message underlying these stories was that neither pure blood nor culture is a necessary attribute of Koreanness. After all, Ward’s blood is “mixed” and he grew up in the United States where, as a young man, he learned almost nothing about his Korean heritage or Korean culture, including how to speak Korean. Ward’s embrace, it is important to emphasize, was different from that of other Amerasians or “mixed blood” entertainers or sports figures in South Korea (as well as in Japan and other Asian countries): he sparked a significant national debate on Korean identity and the country’s “shameful” history of discrimination. Even more, Ward’s success provoked a number of immediate policy changes. Shortly after his visit to South Korea, for example, the Ministry of Education announced that middle school textbooks would no longer describe Korea as a “nation unified by one bloodline,” but instead speak of “a multiethnic and multicultural society.”

Hines Ward (bottom, center), on his visit to South Korea in April 2006, participates in an event held by the Pearl S. Buck International Foundation in Seoul (Source: Korea Times)

Admittedly, the ability of the “Hines Ward phenomenon,” by itself, to sustain a substantive debate on Koreanness, much less fundamentally change attitudes on a society-wide basis, is limited. After a short period of intense interest, the Korean public quickly forgot about Ward and the uncomfortable questions his embrace by Korean society raised. Nonetheless, many Koreans (especially within the government, news media, and academia) did not forget. The national government, in particular, finally began to address decades of unchecked discrimination, both social and institutional, against “mixed-race” Koreans and foreign residents generally. In April 2006, for example, the government granted legal status to people having mixed-race backgrounds and their families, “as part of measures to eradicate prejudices and discrimination against them.” Universities were required to admit a certain number of “mixed-heritage” students; and special programs were proposed to provide educational assistance, legal and financial aid, and employment counseling to poor families.[36] As noted above, the law barring “mixed race” Koreans from serving in the military was also revised in 2006.

These were well-intended measures, but such measures, for the most part, failed to address the underlying source of discrimination, marginalization, and subordination, namely, a national identity that defines difference and diversity as undesirable and, therefore, inferior. This point was underscored by an insightful editorial in the Korea Herald, which argued that the anti-discrimination law was flawed because it equated inter-racial parentage with a physical disability. As the editors put it, “These policy makers seem to believe that like people with physical disabilities, the mixed-race people who have suffered from open and hidden discrimination in this society need social props to help them shed handicaps in finding opportunities in life.”[37] It is worth noting that this bias in the government’s efforts was no accident, for the Korean government had long classified “mix blood” heritage as a type of disability, along with “Harelip, Deformity (Hand or Foot), Prematurity, Mental Illness, Heart Diseases, and Others.”[38]

The question remains: Is Korea ready for a multi-ethnic society? On the one hand, there are positive signs. More and more Koreans, especially those in positions of influence, are cognizant of the issue and many believe that something must be done. In addition, as the discussion above clearly shows, Korean society is more heterogeneous than it has ever been and there is every indication that it will become much more so in the future. Sheer weight of numbers, then, may force Korea to become “ready.” On the other hand, the concept of Korean identity as it has developed historically has left little room for acceptance of social heterogeneity, still less the wholesale transformation of Korean identity.

Who Belongs to Korean Society?

A redefining of national identity does not mean that the concept of Koreanness based on blood and culture must be discarded. In the case of South Korea, this is unlikely, certainly in the short-term. Rather, a redefining of Korean identity can be based on widening the scope of belongingness. Thus, instead of asking, “Who is Korean?” the more appropriate question may be: Who belongs to Korean society? This latter question suggests that the key issue facing Korean society is the ability to not only tolerate or recognize the reality of increasing social heterogeneity, but also to accept and respect ethnic or cultural pluralism as a social good, as a new national ideal. This is the premise behind “multiculturalism,” which might most simply be defined as the acceptance and embrace of cultural difference.

The alternative is widening and deepening social conflict between full-fledged “members” of Korean society and growing numbers of “non-members, including those who may have de jure membership (i.e., citizenship or denizenship), but whose cultural or other ascribed differences are not accepted or tolerated. On this point, it bears repeating that Amerasians—despite their cultural integration into Korean society—have nonetheless suffered severe from discrimination and mistreatment because of their “mixed blood.” In a similar vein, Korea’s “brethren” from China, the Joseonjok, who generally speak Korean and have a strong cultural affinity, have also suffered discriminatory treatment and have effectively been identified as outsiders. This suggests that the primary issue is not necessarily the unwillingness or inability of marginalized groups to “assimilate” (or at least try to assimilate) into Korean society, but rather it is the hitherto impenetrable barrier of a rigidly and narrowly defined conception of belongingness and identity.[39]

As it stands, the pressures for a social or political explosion continue to build. And, while some policy changes are taking place, thus far they have done little to address the underlying source of social exclusion in Korean society. In short, it remains necessary to move toward a more expansive definition of belongingness, toward the creation of a “multicultural nation.”

The Road to a Multicultural Nation: A Comparative Look at the “Australian Model”

To get a better sense of the prospects and concrete possibilities for change in South Korea, it is useful to consider, albeit briefly, a comparative case: Australia. To be sure, in sharp contrast to South Korea, Australia is a country of immigration: historically, a very large proportion of the country’s population has been born outside its borders. In 1901, for example, 23 percent of Australia’s non-Aboriginal population was born overseas. By 1947, the proportion had shrunk to 9.8 percent (due largely to more restrictive immigration policies, which excluded non-European immigrants during the interwar period); but after the end of the Second World War, the numbers again increased: by 1954, 14.3 of Australia’s population was foreign-born. [40] In 2008, the overseas-born population had risen to 22%.[41] Second, despite racially and ethnically laced violence in 2005 (the Cronulla riot[42]), Australia appears to provide a compelling example of cultural or ethnic inclusivity, tolerance, and openness.[43] To be sure, considerable “ethnic tensions” remain in Australian society, most important concerning the two percent of the population of aboriginal origins. There has nevertheless been meaningful, progressive change toward multicultural acceptance of Australia’s substantial immigrant population, much of it in recent years from Asia. Third, and perhaps most saliently, Australia does not have the centuries-old (even millennial-old) tradition of political, linguistic and geographic continuity that Korea purportedly has—a tradition to which most Koreans ascribe the power and embeddedness of Korean identity. On this last point, though, it is important to recognize, at the outset, that the firm belief in the ancient origins of Korea’s ethnic and racial homogeneity is a popular myth. The strong sense of Korean identity and ethnic nationalism is in fact largely a 20th century phenomenon, arising first in reaction to imperial encroachment and Japanese attempts to subjugate and assimilate Koreans into the empire as imperial subjects.[44] Herein lies a key reason for a comparison of Australia and South Korea: both countries share a profound similarity in the colonial origins of the historical construction of a homogeneous national identity. In this regard, too, it is important to understand that, in South Korea, much of this “construction” occurred only in the second half of the 20th century, and that the state played a key role. As we will see in Australia, the construction of an earlier mono-cultural and mono-ethnic national identity was also a product of state action.

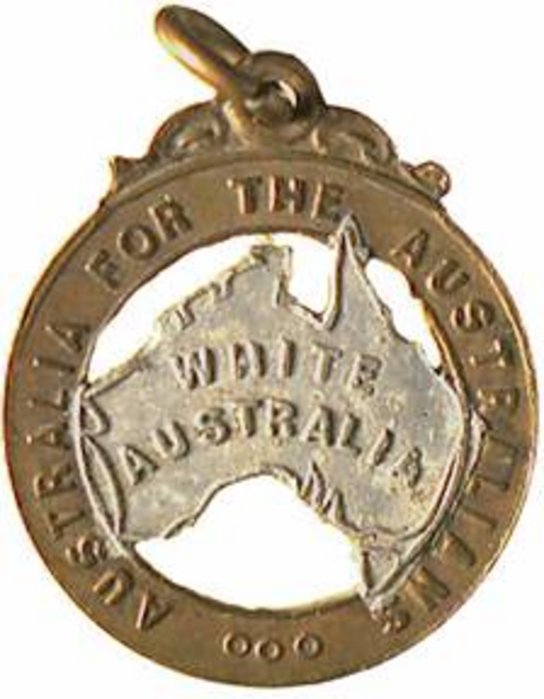

In fact, in Australia, the effort to construct a homogeneous racial and ethnic identity predates the Korean experience by many decades. For nearly a century, beginning in the 19th century, the Australian government attempted to create a mono-cultural, homogenous “white” society—precisely because Australia was a country of immigration. This effort was well reflected in what came to be known as the “White Australia” policy (or, more formally, the Immigration Restrictions Act of 1901[45]). The objectives of the White Australia policy, according to James Jupp, were unabashedly based on a conflation of race and ethnicity: “The Aboriginal population was expected to die out, with those of ‘mixed race’ … assimilating into the majority population to the point of eventual invisibility.”[46] Non-Europeans, moreover, were effectively forbidden to settle in the country. Interestingly, too, the White Australia policy was premised on the same anti-immigration logic we hear in South Korea, Japan and other “homogenous” societies today: Australian officials justified the policy by asserting that anyone who looked different would provoke social unrest in a “totally homogenous” white British society[47] (on its face, a perplexing claim given Australia’s non-white aboriginal population—more on this below.) It is also worth noting, too, that the Australian government also discriminated against non-Anglo and non-Celtic Europeans; as Jupp puts it, “Australia was not settled by ‘Europeans’ but by the ‘British,’ partly to keep ‘Europeans’ out! Its subsequent history was determined by that fact.”[48]

This badge from 1906 shows pride in “White Australia” (Source: Wikipedia)

The logical extreme of the White Australian policy was manifested in the discussions among the governing elite (from the 1930s to 1950s) to “biologically absorb” and/or culturally assimilate the decidedly non-white Aborigine population, although for a long time the question of “where Aborigines fitted into the white nation was generally fudged or ignored for as long as they seemed headed for inevitable extinction.”[49] Ultimately, a policy of assimilation was adopted, but it was one that clearly reflected the then-prevalent and unequivocally racist discourse on the need to maintain national homogeneity (a “pure race”) as the source of national cohesion and national progress. Under Australia’s assimilationist policy (which was officially adopted in 1937, but not formally implemented throughout Australia until 1951), a conscious effort was made to exterminate Aboriginal culture; as part of this policy, children were forcibly taken from their parents and placed in institutions (both government-run and missionary) so that an entire generation could learn “white culture” (a practice highlighted in the feature film, Rabbit-proof Fence). In addition, Aborigines were not allowed to use their native names or practice their traditional culture. It was, in short, an attempt at cultural genocide, elements of which stayed in place until the 1970s.[50]

Australia’s policy of assimilation was not limited to Aborigines. After 1945, and partly in response to increased labor demands and a low fertility rate among white Australians—the same issues, not coincidentally, that Korea (and Japan) face today—the country was forced to accept greater numbers of non-British European migrants.[51] Most of the new European immigrants came from Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, and the former Yugoslavia. Between 1947 and 1953, 170,000 “European” refugees arrived in Australia, followed by subsequent waves of immigrants (including those from Soviet-bloc countries such as Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Latvia, the Soviet Union, and Ukraine). The new immigrants were expected to learn English, adopt existing cultural norms and become indistinguishable from the Australian-born population as rapidly as possible.[52] Given Australia’s history of intolerance and outright racism toward non-Anglo immigrants, however, it is little wonder that the assimilation of “European” immigrants did not work as planned.

The pressure for change, therefore, was building: as more and more of the population was non-Anglo-Celtic, the contradiction between Australia’s mono-cultural and mono-racial national identity and the reality of the country’s ethnic diversity became increasingly difficult to ignore. In addition, in a post-war environment that witnessed the creation of many newly independent states in Asia and the economic rise of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, Australia’s Anglo-centric orientation threatened to alienate all of its closest—and increasingly important—geographical neighbors. This presaged, more broadly, a historic reorientation in Australia. Until the end of the White Australia policy in 1973, the country had formally defined itself as a British society, unequivocally part of the Anglo world. This orientation has certainly not been lost,[53] but in the 1970s Australia explicitly moved toward becoming “part of Asia.” The basic rationale and implications of this shift were spelled out quite clearly in 1984 by then-Prime Minister Bob Hawke, who stated:

A most important step in drawing closer to Asia is that we have accepted and welcomed the fact that people from Asia form part, and most likely an increasing part, of our population, and that Asian culture will, likewise, form an increasing part of our national heritage. No less important has been the transformation of our economic relationship with Asia … we will continue to make this a major priority.[54]

It is worth highlighting the economic rationale in Hawke’s statement, for it reinforces a basic point: the shift from a mono-cultural to multicultural society in Australia was not a product of a new “enlightened” consciousness per se, but of economic forces that were largely responsible for creating a new multiethnic reality. Or as Perry Nolan (a former senior foreign affairs officer) bluntly put it, “The reality is that Australia is located in the Asian/Pacific region. Like it or not, this geographical fact is not going to change Accept it and use it as an advantage …. Refuse to accept our location and opportunities and we will very soon, become the ‘poor white trash of Asia.”[55]

The pressures South Korea faces are not exactly the same, but they are very similar, even profoundly similar. The same can be said of the political and policy choices South Korea faces. On this point, it is worth pointing out that Australia did not move from its racially- and ethnically biased assimilation policy to a multicultural policy in one fell swoop. Instead, the process unfolded gradually. For example, the White Australia policy began to be modified in 1966 (in response to the waves of non-Anglo European immigrants) and was finally abolished in 1973. Two years later, the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975[56] outlawed discrimination based on race and ethnic origin. Other significant changes included the abolition of a discriminatory immigration system that accorded privileges to British settlers over settlers from other countries and final acceptance of Aboriginal people as citizen (1967), although it was not until 1996 that Aboriginal people were legally considered rightful inhabitants of the country with recognized land rights.[57] And, it took another twelve years, for the Australian government to issue a formal apology, which was delivered by Australia’s Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on February 12, 2008.[58] (Importantly, however, many critics, especially in the Aboriginal community, felt that the apology was far from adequate, in part because it does not explain why the government was “sorry,” nor did it provide any concrete plans to redress past wrongs.[59])

More broadly, Australia made two basic shifts in its immigration policy.[60] The first was from “assimilation” to integration, and the second was from integration to multiculturalism. Integration policy, according to Australia’s Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (DIMIA), “recognized that the adjustments required for a successful immigration program should include adjustments by the host society.”[61] In other words, there was increasing recognition that “it was unrealistic to expect migrants to dissociate themselves from their cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and that successful resettlement of new arrivals required greater responsiveness to their needs.”[62] At a concrete level, however, the shift to integration meant providing social services to new immigrants, better educational opportunities, language and translation/interpretation support and assistance for self-help programs (primarily through community-based ethnic organizations).[63]

The positive effects of integration policies can be very limited, however, if the “adjustments by the host society” fail to address adequately larger issues of national identity and belongingness. After all, “integration” means very little if racial and ethnic discrimination not only remains firmly embedded in society at large, but is also entrenched in the institutions of governance. Further, integration means very little if certain groups are still viewed—and treated—as subordinate and inferior to the dominant culture. These shortcomings were recognized in the Galbally Report,[64] which, as Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser noted, “… identified multiculturalism as a key concept in formulating government policies and recognized that Australia was at a critical stage in its development as a multicultural nation.”[65] The Galbally Report reinforced and extended existing integration policy, but also was the first substantive step in dealing with issues of national identity. For example, the Report led to the promotion of multicultural education in government and non-government schools; the establishment of the Australian Institute of Multicultural Affairs (designed to provide policy advice to the Commonwealth on multicultural issues); and the creation of Channel 0/28, which Fraser called “a service unique in the world.”[66] (This new channel was originally designed to broadcast only “multicultural”—as opposed to “ethnic”—programming that would be of interest to all Australians. The first program shown was a documentary on multiculturalism entitled “Who Are We?”)

This was just the beginning of a long, complicated process, which continues today. It is, more simply, a work in progress. And while there are many critics of this process, it is fair to say that Australia has witnessed a sea change in that the question, “Who is Australian?” is no longer subject to a clear-cut answer based on race and Anglo-Celtic values. At the same time, it is important to recognize that multiculturalism has not entailed a rejection of “core values” for Australian society and national identity. Instead, the model of Australian multiculturalism explicitly eschews cultural relativism by consciously constructing an “over-arching framework of values”, most of which are derived from the Anglo-Celtic cultural tradition and then molded into their present Anglo-Australian form.[67] This framework has not been entirely successful. But this should not be a surprise given that successful completion of the process requires, as Smolicz puts it, “the acceptance of a culturally pluralist solution by the Anglo-Celtic dominant majority—with some values shared, and others preserved and adapted by constituent ethno-cultural groups, within the new nation.” More to the point, Smolicz tells us that the “degree of acceptance of minority ethnic [sic] as ‘real Australians’ (i.e., as members of the nation in its most basic ideological/emotional sense) has not yet been fully accomplished.” [68]

Ironically, the lack of complete success in Australia is a good sign for South Korea. It is good in the sense that Australia represents a “realistic” model of the challenges Korea will likely face in the transformation from a mono-cultural society to multicultural one. One of these challenges, for example, is likely (if not almost assuredly) the rise of xenophobia generally, but also most specifically in the form of political parties, such as the One Nation party in Australia, which has railed at the “Asianisation” of Australia and against the policy of multiculturalism in general. More generally, Australia’s still imperfect path to multiculturalism demonstrates an essentially common sense—but easily forgotten—lesson: the type of fundamental political and social transformation that multiculturalism represents in a formerly “homogenous” society will requires decades of ongoing struggle, with many steps backward for every few steps forward.

Conclusion: Who are the Agents of Multiculturalism?

The government and people of South Korea have a tremendous opportunity to not only accept the reality of increasing social heterogeneity, but also to embrace a new multicultural vision. This will not be easy, for Korea’s sense of national identity has deep roots; the belief in the oneness of blood and culture is embedded in the psyche of many Koreans. As in Australia, however, it is possible to uproot even the most ingrained orthodoxies. The first step is to recognize that ethnic and cultural diversity is not a threat to Korean identity and national strength, but a potential and potentially potent source of new creative energy. This is particularly important in the current era, one in which increasing “globalization” has not only put more and more pressure on all societies to innovate and grow in new directions, but has also put pressure on states to become more inclusive. Even more, a mono-cultural, race-based based national identity that subordinates and marginalizes other ethnic and cultural groups has become a dangerous anachronism. It not only breeds divisiveness and social tension, but also, and more importantly, can barely be justified in a world where human rights has become an accepted norm of global society. Despite all this, for many people it is difficult to imagine a fundamental shift in the notion that Korea is a “single-race country.”

The apparent lack of space for significant change, though, should not be taken for granted. Indeed, since the end of Japanese colonial rule, South Korea has witnessed tremendous social, political, and economic change. Just two generations ago, few observers would have given South Korea any chance to become one of the largest economies in the world and a major competitor in some of the most advanced markets. And, just 20 years ago, few Koreans could have imagined that the country would host hundreds of thousands of foreign workers, or that Korean men—in the most conservative and traditional parts of the country—would be marrying women from China and Vietnam in increasing numbers. Granted, these latter two changes are not a product of a new enlightened view among South Koreans. But, this only helps underscore a key point: sometimes societies are compelled to change.

This said, there is nothing automatic or inevitable about the transition to a multicultural society. If it happens in South Korea, it will be the result of a political process involving many actors. Some of these actors will be the new immigrants themselves as they press for greater recognition of their rights within Korean society. Significantly, this has already happened to with regard to labor and human rights for foreign migrant workers—an issue I examine at length elsewhere.[69] The step toward political and residency rights, however, is much larger one to take. Many foreign migrants—primarily non-skilled workers—are uninterested in taking this step. They simply want a secure short-term job that allows them to earn a decent wage and work under satisfactory conditions. For others, though, political and residency rights are important. They understand, too, that it is a two-way street: they must adapt to Korean society just as Korean society must adapt to them. While almost no data are available, anecdotally it appears that many long-term “residents” have learned the Korean language and Korean customs (in my interviews with a range of foreign workers, for example, all spoke Korean). For foreign women who have married Korean men, it is virtually de rigueur to learn Korean and to adapt, almost immediately, to traditional Korean cultural practices (in a manner, to become “more Korean” than most Korean women).

Korean “liberals” must also play a key role, as they have already done in the struggle for migrant worker rights.[70] More specifically, the network of Korean non-governmental organizations (NGOs) must continue to provide financial, organizational and logistical support to foreign migrants/immigrants, whose numbers and resources are still relatively small and unstable. For a long time, Korean NGOs glossed over or ignored the issues of political and residency rights, particularly as they apply to foreign workers (as opposed to foreign spouses). But, the persistence of activists in the foreign worker community, combined with the fortuitous success of Hines Ward, has helped to shift or redirect the discourse from one focused almost exclusively on labor and human rights to one increasingly aimed at the rights of belongingness, denizenship and citizenship.

Finally, as in Australia, the state will have to play a central role. Minimally, the state must construct, whether reactively or proactively, the over-arching legal and institutional framework within which the broader shift toward a multicultural society unfolds. But the state must also balance between the centrifugal forces of ethnic diversity and the centripetal need for national cohesion. To achieve social and political stability, all major “groups” in society—from majority to minority—need a basic level of security. Obviously, this is not easy to achieve; arguably, however, the state is the only institution capable of fulfilling this task. Whether the Korean (or Japanese) state is up to this task remains an open question. But it is clear that it can be done.

Postscript

I addressed these issues in the years 2006 and 2008. In June 2009, the Korean Immigration Service released a report entitled, The First Basic Plan for Immigration Policy, 2008-2012. This 120-page report, in some respects, is a blueprint for a transition to a multicultural society in South Korea, along the lines I have suggested here. It is a very general blueprint, to be sure, but it acknowledges the inexorability of global immigration to South Korea (for non-skilled workers, high skilled workers, foreign spouses, the Korean “Diaspora,” and others), and addresses key issues: social integration, citizenship and naturalization laws/procedures, civic education on multiculturalism, educational policies (K-12), etc. Of course, broadly written policy documents or white papers, may ultimately have little concrete impact. If nothing else, though, the Plan signifies a dramatic, even fundamental, shift in South Korea’s official perspective on immigration: multiculturalism, inclusivity, and integration are key themes running throughout the document.

Timothy Lim is a professor of Political Science at California State University, Los Angeles. He is the author of Doing Comparative Politics: An Introduction to Approaches and Issues and of numerous articles on transnational worker migration to South Korea.

You can find more information about the author at his instructional website: click here.

I would like to thank Mark Selden, who not only provided many useful suggestions for the preparation and revision of this paper, but also encouraged me to expand and deepen my original short essay for publication in Japan Focus. I would also like to thank the reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Recommended citation: Timothy Lim, “Who is Korean? Migration, Immigration, and the Challenge of Multiculturalism in Homogeneous Societies” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 30-1-09, July 27, 2009.

Notes

[1] Quoted in “Korea Greets a New Era of Multiculturalism,” Korea Herald, July 25, 2006.

[2] The concepts of race and ethnicity are social constructions, collective identities formed through historical and socio-political processes. This is a generally accepted view with regard to ethnicity, which is widely understood as a cultural phenomenon: a collective identity based on shared customs and values (at times rooted in religious beliefs), a common language or dialect, and other social characteristics and practices embraced by a group, community or society. Race is a far more controversial concept, especially when used to describe supposedly distinct—and inherently separate—groups on the basis of genetic or biological characteristics. The “biological” usage of race has long been discredited among social scientists, most of whom understand race as a symbolic marker of difference

[3] In 2003, the number of ethnic Koreans living in regions other than the Korean peninsula was over 6.3 million (according to a report issued by the Ministry of Diplomacy and Commerce). This figure represents 14% of the entire Korean population. Cited in Lee Jun-shik, “The Changing Nature of the Korean People’s Perspective on National Issues, and Fellow Koreans Living Abroad,” The Review of Korean Studies, v. 8, no 2 (2005): 111-140.

[4] The term “Amerasian” was originally coined by Pearl S. Buck, who used it to refer to any child born to an “Asian” parent and an American parent in the aftermath of U.S. military interventions in Asia. Thus, there are Amerasian children in Korea, the Philippines, Japan, and most prominently, Vietnam. The fathers of most Amerasian children are U.S. soldiers.

[5] See, for example, Mary Lee, “Mixed Race Peoples in the Korean National Imaginary and Family,” Korean Studies, vol. 32 (2008), pp. 65-71; and Katherine Moon, Sex Among Allies: Military Prostitution in U.S.-Korea Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997).

[6] Park Kyung-Tae, “Left Behind: Amerasians Living in Korea,” paper presented at the Korean Nation and Its ‘Others’ in the Age of Globalization conference, University of Hawaii, April 20-21, 2007.

[7] Lee, “Mixed Race Peoples,” p. 59.

[8] According to Pearl S. Buck International, in 2002, almost 10 percent of Amerasians in South Korea failed to enter or complete primary school (compared to a national completion rate of virtually 100 percent) and 17.5 percent did not graduate from middle school (cited in Lee, “Mixed Race Peoples, p. 60). Overall, the drop out rate for Amerasians was 47 percent (cited in Park, “Left Behind”). Dropout rate? Through high school? Explain or drop sentence.

[9] Based on a survey of 101 Amerasians conducted by Park Kyung-Tae in 2006. Park describes the situation this way: Amerasians “… are employed mostly in construction, manufacturing factories, restaurants, etc. Only 24 percent have regular jobs.” Further, according to Park’s survey, the average monthly income for Amerasians was 1,460,000 won, which was less than half the national average of 3,068,900 won. Park, “Left Behind.”

[10] Lim, “Fight for Equal Rights,” pp. 338-339.

[11] Lim, “Fight for Equal Rights,” pp. 340-341.

[12] See Timothy C. Lim, “Racing from the Bottom in South Korea? The Nexus between Civil Society and Transnational Migrants,” Asian Survey, vol. 43, no. 3 (2003), pp. 423-442.

[13] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism (London and New York: Verso, 2006, revised ed.).

[14] Gi-wook Shin, “Ethnic Pride Source of Prejudice, Discrimination,” Korea Herald, August 3, 2006.

[15] An interesting discussion of this issue is available as an audio program on United States Institute of Peace website. See “What Does it Mean to be Iraqi? The Politics of Identity in Iraqi,” a public meeting of the Iraq Working Group, October 17, 2006, online recording

[16] See my discussion of comparative methodology in Doing Comparative Politics: An Introduction to Approaches and Issues (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2006), chs. 1 and 2.

[17] By the official government definition, a foreign resident is any non-citizen residing in Korea for 91 days or longer. There are a number of minor exceptions to this rule, including any member of diplomatic delegation or consular corps, members of international organizations, and Canadian citizens residing in Korea up to six months. The number of short-term (91 days to one year) foreign residents has remained fairly constant, so the recent and dramatic increase in the overall foreign resident population is overwhelmingly based on individuals staying in South Korea for longer periods of time.

[18] Based on data from South Korea’s Ministry of Justice; cited in “Korea Heads Toward a Multicultural Society,” Korea Herald, June 6, 2008.

[19] “Korea Heads Toward a Multicultural Society.”

[20] Figures cited in Seol Dong-Hoon, Migrants’ Citizenship in Korea: With a Focus on Migrant Workers and Marriage-based Migrants,” unpublished paper (n.d.). Data collected by Seol from the Statistical Yearbook of Departures and Arrivals released by the Ministry of Justice.

[21] Cited in Korean Immigration Service (KIS), The First Basic Plan for Immigration Policy, 2008-2012 (Seoul, June 2009). p. 45.

[22] KIS, The First Basic Plan, p. 45.

[23] Lee Yean-Ju, Seol Dong-Hoon, and Cho Sung-Nam, “International Marriages in South Korea: The Significance of Nationality and Ethnicity,” Journal of Population Research, vol. 23, no. 2 (2006), p. 166-167.

[24] KIS, The First Basic Plan, p. 45. This figure also includes Korean men engaged in fishing.

[25] Global hypergamy refers to a pattern of movement in which brides from more remote and less developed locations to increasingly developed and less isolated ones, and globally from the poor and less developed global south to the wealthier and industrialized north. For further discussion, see Nicole Constable, “Introduction: Cross-Border Marriages , Gendered Mobility, and Globaly Hypergamy,” in Nicole Constable, ed., Cross-Border Marriages: Gender and Mobility in Transnational Asia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), pp. 1-16.

[26] It is useful to note that global hypergamy is not as clear cut as it may appear on the surface. Freeman, for example, points out that in the case ethnic Korean brides from China who marry Korean men, “…the complex and conflicting ways in which constructions of nationality, gender, and geography intersect in these marriages make it difficult to distinguish those ‘in charge’ from those who are deprived.” Caren Freeman, “Marrying Up and Marrying Down: The Paradoxes of Marital Mobility for Chosonjok Brides in South Korea,” in Constable, ed., Cross-Border Marriages, pp. 80-100.

[27] For an extended discussion of the role of the Unification Church, see Kim Minjeong, “‘Salvation’ Through Marriage: Gendered Desire, Heteronormativity, and Religious Identities in the Transnational Context” (paper presented at the Gender, Religion & Identity in Social Theory Symposium, Blacksburg, VA, April 2009).

[28] The factors behind the upsurge of international marriages in South Korea are too complex to adequately cover here. But several studies available provide in-depth discussion of these factors. See Nancy Abelman and Hyunhee Kim, “A Failed Attempt at Transnational Marriage: Maternal Citizenship in a Globalizing South Korea,” in Constable, ed., Cross-Border Marriages , pp. 101-123; Lee Hye-Kyung, “International Marriage and the State in South Korea: Focusing on Governmental Policy,” Citizenship Studies, vol. 12, no. 1 (February 2008), pp. 108-123; and Freeman, “Marrying Up and Marrying Down.”

[29] See Park, “Left Behind.” Park estimates that, as of 2000, there were fewer than 1,000 Amerasians residing in South Korea, maybe as few as 433.

[30] “Educating Children of Foreign Residents,” Korea Herald, June 24, 2008.

[31] “Diversity Causes Korea to Face New Challenges,” Korea Times, February 24, 2008.

[32] The Korean National Statistical Office reported the figure of 1.08 in 2006. Over a five-year period from 2000 to 2005, however, the United Nations, World Population Prospects 1950-2050: The 2006 Revision gave a figure of 1.20, which was still lower than or equal to all countries except for Hong Kong (SAR). Figures are cited from the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Human Development Report. Available here.

[33] A number of other scenarios were also discussed, but most did not anticipate a further significant decline in Korea’s fertility rate. See United Nations Population Division (UNPD), “Country Results: Korea,” in Replacement Migration: Is it a Solution to Declining and Ageing Population? (United Nations, 2001), available here.

[34] UNPD, “Country Results: Japan,” in Replacement Migration.

[35] “Get Ready for a Multi-Ethnic Society [Editorial],” Hankyoreh, June 29, 2005.

[36] “Korea to Scrap Mixed-Race Discrimination,” Korea Times, April 8, 2006.

[37] “Law for the Mixed-Blood?” Korea Herald, April 11, 2006.

[38] Cited in Lee, “Left Behind.” These classifications come from a government prepared handbook on adoptions entitled, Adoptees by Types of Disability: Domestically and Abroad.

[39] Despite familiarity with Korean language and culture, ethnic Koreans from China often find it hard to thoroughly assimilate into Korean society. Freeman, for example, points out that Joseonjok women are “[r]eadily identified by their style of dress, their patterns of speech and pronunciation, and their unfamiliarity with Korean linguistic and behavioral codes of politeness. [Joseonjok] are for the most part unable to ‘pass’ as South Koreans.” Freeman, “Marrying Up and Marrying Down,” p. 95.

[40] All figures cited in Department of Immigration and Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs (DIMIA), Report of the Review of Settlement Services for Migrants and Humanitarian Entrants (Canberra: Commonwealth Publishing Service, 2003), pp. 23-25.

[41] Larry Rivera, “Australian Population: The Face of a Nation,” available here.

[42] The Cronulla riot involved a violent clash between white Australian “surfies” and “Arab” youth from the Western suburbs of Sydney. To many in Australia, the riot was understood as a backlash against Australia’s turn toward multiculturalism, as an effort to protect Australia’s national identity by drawing limits around multiculturalism. For a fuller discussion, see Andrew Lattas, “’They Always Seem to be Angry’” The Cronulla Riot and the Civlilising Pleasures of the Sun,” Australian Journal of Anthropology, v. 18, no. 2 (December 2007), pp. 300-319.

[43] For the most part, these traits have been confirmed through empirical research. In a national survey in Australia, for example, four academic researchers drew this conclusion: “The overall picture is one of a fluid, plural and complex society, with a majority of the population positively accepting of the cultural diversity that is an increasingly routine part of Australian life. … In practice, most Australians, from whatever background, live and breathe cultural diversity …. Cultural mixing and matching is almost universal. There is no evidence of ‘ethnic ghettos.’” Ien Ang, Jeffrey E. Brand, Greg Noble and Derek Wilding, “Living Diversity: Australia’s Multicultural Future,” Humanities and Social Science Papers (Bond University, 2002), p. 4. Available here.

[44] Shin, “Ethnic Pride Source of Prejudice, Discrimination.” Shin provides a much fuller and scholarly treatment of this subject in his book, Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics and Legacy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

[45] Although passed in 1901, the Immigration Restrictions Act more or less codified existing practices that had been going on for several decades.

[46] James Jupp, “From ‘White Australia’ to ‘Part of Asia’: Recent Shifts in Australian Immigration Policy Toward the Region,” International Migration Review, v. 29, n. 1 (Spring 1995), p. 208.

[47] James Jupp, From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration (Cambridge University Press, 2002), p. 9.

[48] Jupp, From White Australia, p. 3.

[49] Anthony Moran, “White Australia, Settler Nationalism and Aboriginal Assimilation,” Australian Journal of Politics and History, v. 51, no. 2 (2005), p. 172.

[50] One scholar argues that it was not just cultural genocide, but simply genocide. See Paul R. Bartrop, “The Holocaust, the Aborigines, and the Bureaucracy of Destruction: An Australian Dimension of Genocide,” Journal of Genocide Research, v. 3, no. 1 (2001), pp. 75-87. Similarities and differences to Japanese colonial policies in Korea are striking. Like the Australians, Japan sought to assimilate Koreans in numerous ways including banning the Korean language in the schools and enforcing Japanese names. For analogies to the practice of breaking up families of aboriginal Australians, however, it is better to turn to US practices with respect to Indian families in the first half of the twentieth century.

[51] Increasing prosperity and lower unemployment in post-war Britain also stemmed the flow of Anglo immigration to Australia.

[52] Stephen Castles, “Australian Multiculturalism: Social Policy and Identity in a Changing Society,” in Gary Freeman and James Jupp, eds., Nations of Immigrants: Australia, the United States and International Migration (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), p. 185.

[53] As Jupp notes, “ … despite the growth of Asian studies and the current popularity of Japanese as a school subject, the severance from Britain has not involved a massive shift in cultural orientation.” Jupp, “From ‘White Australia’ to ‘Part of Asia,’” P. 211.

[54] Robert J. Hawke, “Australia’s Security In Asia”; cited in Denis McCormack, “Immigration and Multiculturalism,” in Your Rights ’94, Australian Civil Liberties Union (Carlton, Australia: ACLU, 1994), p. 10.

[55] Perry Nolan, “Ability the Only Criterion that Matters in Migration,” The Australian Financial Review, September 5, 1988.

[56] The text of the Act is available here.

[57] Smolicz, “Globalization and Cultural Dynamics in a Multiethnic State,” p. 32.

[58] The full-text of the speech is available here.

[59] A year after the speech, for example, Michael Mansell (director of the Tasmanian Aboriginal Center) argued that Rudd was hiding behind his largely symbolic apology to avoid the hard work of improving Aboriginal living standards, which are among the lowest in the world. As Mansell put it, “Aboriginal people, and especially members of the stolen generations, are probably worse off now than when Kevin Rudd made the apology a year ago.” Even more, Mansell asserted: “There is no land rights for the dispossessed, no compensation for the stolen generations, the health standards are not improving and the Aboriginal imprisonment rate continues to climb. The apology has provided the Rudd government with a political shield against criticism of its failures in Aboriginal affairs.” Cited in “Rudd Under Fire a Year After Apology to Aborigines,” available here.

[60] The focus in this section is on non-Aboriginal communities in Australia. This is largely because government policies toward the Aboriginal communities and other ethnic communities have proceeded along different tracks. Until recently, the basic policies toward Aboriginal communities were premised on deliberately encouraging separate traditional Aboriginal communities. These policies have not prevented integration (for example, 70 percent of Aborigines are married to non-indigenous spouses, live in urban areas, and profess Christianity), but they have helped to create remote Aboriginal communities that suffer from poverty and other social problems. Peter Howson, “Aboriginal Policy,” Melbourne Age, April 20, 2004.

[61] DIMIA, Report of the Review of Settlement Services, p. 27.

[62] DIMIA, Report of the Review of Settlement Services, p. 27.

[63] DIMIA, Report of the Review of Settlement Services, p. 28.

[64] The official title of the Galbally Report is the Report of the Review Post-Arrival Programs and Services to Migrants, which was prepared b a 4-person committee and chaired by Frank Galbally. For a brief discussion of the report, see Leslie F. Claydon, “Australia’s Settlers” The Galbally Report,” International Migration Review, v. 15, no. 1/2 (Spring-Summer 1981), pp. 109-112.

[65] Malcolm Fraser, “Inaugural Address on Multiculturalism to the Institute of Multicultural Affairs,” The Malcolm Fraser Collection at the University of Melbourne, November 30, 1981. Available here.

[66] Fraser, “Inaugural Address on Multiculturalism.”

[67] Smolicz, “Globalization and Cultural Dynamics in a Multiethnic State,” p. 32.

[68] Smolicz, “Globalization and Cultural Dynamics in a Multiethnic State,” p. 32.

[69] See, for example, “Racing from the Bottom in South Korea? The Nexus between Civil Society and Transnational Migrants in South Korea,” Asian Survey vol. 43, no. 3 (2003), pp. 423-442; and “Democracy, Political Activism and the Expansion of Rights for International Migrant Workers in South Korea and Japan: A Comparative Perspective,” IRI Review, vol. 11 (Spring 2006), pp. 156-204.

[70] For a discussion of this issue, see my 2002 article, “The Changing Face of South Korea,” in The Korea Society Quarterly (Fall/Summer). Available here.