The Forgotten Japanese in North Korea: Beyond the Politics of Abduction

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

The Girl in the Ice-Cube

For the past few years, international travelers leaving Japan’s major airports have been confronted with a written instruction as they queue in front of the passport control booths. Displayed only in Japanese, and thus aimed specifically at a domestic audience, the instruction informs Japanese people that they should “voluntarily refrain” [jishuku suru] from visiting North Korea [the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK]. This is part of the package of sanctions which was imposed on North Korea by the Japanese government in 2006, following the DPRK’s nuclear test, and which have remained in place ever since.

When I passed through Narita Airport on my way to the United States in December 2008, I found that this call for “voluntary restraint” had been joined by another Japanese official message about North Korea. The large screens in the airport waiting lounges, which generally display glimpses of alluring tourist destinations interspersed with travel health and safety advice, were now intermittently broadcasting an advertisement with imagery so striking that it seized my attention even before I grasped the message that it conveyed.

Arriving in the lounge mid-way through the advertisement, I initially saw on the screen a young man struggling to free himself from a cube of ice, within which he was frozen. This was followed by other similar images – another ice-cube contains a girl in school uniform, whose faint voice pleads, “please help me get back home”. Then the camera pans back, to reveal a map of North Korea dotted with similar ice-cubes – ten, eleven, maybe twelve of them. Next, the scene shifts to the more familiar image of Yokota Shigeru and Yoshie, the parents of young abduction victim Yokota Megumi, meeting George W. Bush in the White House; and the meaning of the advertisement becomes clear. As the narrative explains (in both Japanese and English): “Japanese abductees are still being held by North Korea for thirty years now. The abduction issue is still unresolved. The abductees need your assistance. They need your words and actions.”1

The figures in the ice-cubes, then, represent the Japanese citizens abducted by agents of the North Korean state in the 1970s and early 1980s. The advertisement, entitled “The Abduction Problem: Imprisoned Girls” [Rachi Mondai: Torawareta Shōjotachi] was commissioned by the Japanese government’s Headquarters for the Abduction Issue [Rachi Mondai Taisaku Honbu] and released to coincide with the arrival of foreign dignitaries and journalists for the Hokkaido Summit in July 2008, and continued to be broadcast at major airports around the country until the end of January 2009 as part of a campaign to “raise awareness” about the kidnapping issue.

The message graphically communicated by the advertisement is that many (indeed probably all) of the Japanese abducted by North Korea in the 1970s and early 1980s are alive and are being held prisoner in the DPRK. There is no hint here of the fact that it is actually unknown whether any of the Japanese abduction victims (other than those who have already returned to Japan) are alive today. At the time of Prime Minister Koizumi’s visit to Pyongyang in 2002, the North Korean government admitted to kidnapping twelve Japanese citizens, of whom (it said) only five were still alive. The five surviving abductees were allowed to make a home visit to Japan in October 2002. Despite a commitment to the North Korean government that this initial visit to Japan would be a temporary one, on the instance of the Japanese government, they remained there permanently, and were later joined in Japan by their immediate families. While North Korea states that all the abductees have been accounted for, the position taken by abductee support groups in Japan, and reflected in the Japanese government’s advertisements, is that all the remaining kidnap victims are still alive and being forcibly prevented from returning home. The Japanese authorities also claim that at least four, and probably more, additional abductions were carried out by the DPRK. While the information provided by North Korea leaves many questions unanswered, however, some of the evidence presented by the Japanese government to support its contentions is also debatable.2

The abductions were a state crime and an extreme violation of human rights. The world should indeed be trying to find a way of ensuring that an effective investigation of the fate of these victims is carried out as soon as possible, and, if any are still alive, they should be given the chance to return to Japan immediately. But the stark imagery of “The Abduction Problem: Imprisoned Girls” also points to other, wider problems.

The schoolgirl in the ice cube, her hands groping helplessly at the transparent walls that surround her, conveys a complex symbolism. At one level, this image is intensely evocative of the way in which the abduction story has been told and re-told in the Japanese media. The victim is young – frozen in time, it seems, at the moment of her abduction, just as the faces of the abductees on countless posters and magazine covers are frozen in the eternal youth of their lost lives in Japan. It is almost as though, like the legendary Urashima Tarō, they are expected to return to the place of their birth untouched by time and by their experiences in that unimaginable other world in which they have spent the past thirty years. The structure of the advertisement focuses on the young girl: the title, indeed, multiplies her into plural “young girls”. This again is emblematic, for the figure of Yokota Megumi, a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl at the time she was kidnapped, has come to represent the abduction story in the minds of many people in Japan and worldwide, even though all the other abductees were adults.

The image of the block of ice is also a powerful symbol of the entire state of Japan’s relationship with North Korea. Since the government of the DPRK admitted to the abductions in September 2002, this issue has acted like a curse cast upon the Japan-North Korea relationship, freezing communication and exchange. The chill created by the abductions, and further deepened by the North Korean nuclear and missile test, has immobilized Japanese discourse about North Korea. The issues of the abductions and the nuclear threat became fused into a single menacing image around which this discourse endlessly circles. The result has been a freezing of the imagination: an inability to envisage any discussion of, or relationship with, North Korea which does not centre on the abductions and nuclear weapons. And, since memory and imagination are inevitably intertwined, this restriction of the imagination has also involved a closing off of memory, consigning to oblivion many aspects of the past century of complex interaction between Japan and the northern half of the Korean Peninsula.

The opening of cautious communications between the DPRK and the USA and the election of a new Democratic Party government in Japan in the middle of 2009 create the possibility that this ice-age in Japan-North Korea relations may be about to give way to a gradual thaw. In that context, this paper explores the fate of a group of people who, as much as any, have been victims of the freeze. Despite the Japanese media’s obsessive focus on the abduction issue, the remaining abductees (if still alive) are not the only Japanese in the DPRK. An examination of the fate of the other Japanese in North Korea casts light on long-neglected facets of the Japan-DPRK relationship, and highlights the need for a new and broader approach to dialogue between the two countries.

Staying On

The first, and perhaps the most comprehensively forgotten, group of Japanese in North Korea are those who (for one reason or another) remained there after the collapse of the Japanese Empire in 1945. Following Japan’s defeat in the Asia-Pacific War, some 320,000 Japanese people (including both civilians and military) were repatriated to Japan from the northern half of the Korean Peninsula, either directly or via southern ports such as Busan.3 Many suffered traumatic experiences as they fled in fear before the advancing Soviet forces, sometimes facing anger and violence at the hands of those they had colonized.

But not all returned. Some, particularly Japanese women married to Korean men and children separated from their parents, remained in the north and witnessed the transformation of the Soviet occupied zone into the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. And, almost half a century before Prime Minister Koizumi’s 2002 visit to Pyongyang, the fate of these Japanese in North Korea became the focus of moves which initiated the first cycle of relations between Japan and the DPRK.

Some three years after the end of the Korean War and more than a decade after the collapse of Japan’s empire, one of the first tangible signs of an emerging relationship appeared when a ship set sail for Japan from North Korea carrying thirty-six Japanese passengers, of whom seventeen were former Japanese colonial settlers, while the remaining nineteen were their children. Of the adults who made this journey in April 1956, only one was a man: a migrant from Osaka who had left Japan in 1929, trained as a printer and subsequently had been employed by the North Korean Ministry of Culture’s propaganda section.4 Most of the women had been married to Koreans but had become widowed or separated from their husbands. A Japan Red Cross official who traveled with them noted that many of the women cried as the coast of Korea disappeared from view, but that the children showed remarkably little emotion. There were further tears mixed with cries of delight as the Japanese coast appeared, and again as the returnees were reunited with their families.5

The process which finally brought these colonial migrants home to Japan, began in 1953, when the President of the Japan Red Cross Society, Shimazu Tadatsugu, visited Moscow and raised with the Soviet authorities the problem of Japanese who were believed to be still living in North Korea.6 His Soviet counterparts advised him to communicate directly with the North Koreans, so in January of the following year, Shimazu wrote a telegram which was conveyed to the North Korean Red Cross via the League of Red Cross Societies in Geneva.7 The response was relatively encouraging. One month later, the North Korean Red Cross telegraphed back to say that “if there are those among the Japanese residing in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea who wish to return to their country”, the DPRK Red Cross would be happy to help them.8

The practical problems, however, were great. Japan, along with most other non-Communist countries, had no diplomatic ties to the DPRK. There was no trade, no postal communication and no transport link between the two neighbouring countries. Contacts were therefore facilitated by private intermediaries such as former Asahi Newspaper Moscow correspondent Hatanaka Masaharu, who visited Pyongyang in May 1955.9 In November of the same year, Hatanaka also played a central role in establishing the Japan-Korea Association [Nitchō Kyōkai], which aimed to promote better relations between Japan and North Korea.

From 27 January to 28 February 1956 the Japan Red Cross, working (rather reluctantly) in conjunction with the Japan-Korea Association, held a conference with its counterpart in Pyongyang. Red Cross negotiations to secure the return of Japanese from China and the Soviet Union had helped to open up channels of communication and trade between Japan and these communist countries, in the Soviet case leading to the normalization of diplomatic relations in 1956, and it seemed likely that the 1956 Pyongyang Conference might also open doors to closer political and economic links with North Korea. However, the Conference became entangled instead in the murky politics of the repatriation of ethnic Koreans to the DPRK (discussed below). Its only positive outcome was the return of the boatload of Japanese former colonial settlers and their children from the DPRK to Japan.

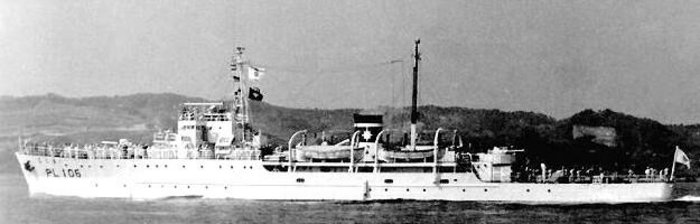

The repatriation ship Kojima, on which 36 Japanese citizens returned from the DPRK to Japan in April 1956

Throughout the last months of 1955 and the early part of 1956, the fate of the “left-behind Japanese” [zanryū Nihonjin] in North Korea attracted much Japanese media interest. By this time, the mass repatriation of Japanese from the colonies and occupied areas had been completed, and it would not be until the 1970s that the media turned its attention to the issue of the substantial number of former settlers in the pre-war quasi-colony of Manchukuo who still remained living in China after the war.10 Although the story of the “left-behind Japanese” in North Korea did not capture the headlines quite as dramatically as the abduction issue would three-and-a-half decades later, the parallels between the two events are interesting. Estimates of the number of Japanese still living in North Korea in 1956 varied wildly. Some sources suggested a figure as high as two thousand.11 But many of those last heard of in North Korea had lost touch with their families long ago, and of these, some had almost certainly perished during the collapse of the Japanese empire or during the Korean War. The Japan Red Cross initially believed that it had identified around fifty Japanese who wished to return to Japan immediately.12 However, for reasons that are unclear, almost a third of these people ultimately changed their minds, leaving only thirty-six returnees to board the repatriation vessel Kojima, bound for the Japanese port of Maizuru, in April 1956.13

In some ways, the treatment given to these departing colonizers by the North Korean government seems relatively generous. Each was given a parting present of 50,000 yen – a considerable sum of money in the values of the time. But most still felt anxiety at the life that awaited them in Japan. The Japan-Korea Association and Japan Red Cross Society had reportedly promised to help the returnees find work, but a month after their return, many of them were unemployed and struggling to adapt to their new life. One woman who had come back to Japan with her two children told the media that she had received no assistance with resettlement from the Japanese side. Her first husband had died soon after the end of the war, and she had remarried a North Korean merchant. However, he had fled south with the US forces during the Korean War, leaving her in the North where, because of her husband’s departure, she was regarded with suspicion as the wife of a “traitor”. This was why she had chosen to return to Japan. She found it difficult, she said, to adjust to a society where work was not guaranteed, and her children, who spoke only Korean, were still battling the language barrier.14 One cannot help wondering what became of them later.

The repatriates reported that they believed there to be about 600 Japanese people – some 200 adults and 400 children – still in the DPRK.15 A considerable number were said to be hoping to return to Japan, and the newspapers actually published lists of the names of several dozen of these would-be returnees, together with details of the places where they were living. However, the returnees who arrived in April 1956 were the last Japanese colonial settlers to be repatriated from North Korea. After that, the Japanese media lost interest in the story, and the Japan Red Cross Society, which had become deeply involved in the much larger venture of repatriating Koreans from Japan to North Korea, did little to follow up their cases.

So they remained in the DPRK. In 1994, Japan’s Health and Welfare Ministry was aware of around seventy Japanese former colonial settlers still living in North Korea.16 Some, as well as their offspring, are still there today. In December 2008, Murayama Hisako a ninety-nine year old woman living in Yokohama, died, thereby losing a battle she had been waging for the past half century: a struggle with officialdom for a chance to be reunited with her daughter Setsuko, left behind in North Korea as a teenager at the end of the Asia-Pacific War.17 The stories of such migrants, and the invisible links that they create between Japan and North Korea, are another part of the relationship which has disappeared into the historical void created by more recent political tensions.

The “Repatriation” of Japanese Citizens to North Korea

But the Japanese “left behind” by the vanished empire are neither the only nor the largest group of Japanese in the DPRK today, for in the 1960s this group of expatriates was joined by another influx of Japanese residents. Their migration was part of a mass movement of people generally known as the “repatriation project” which began fifty years ago this year, and between 1959 and 1984 resulted in the resettlement of just under 100,000 people from Japan to the DPRK, with the vast majority leaving Japan in the first three years of the 1960s. Well over 90% of these border-crossers were ethnic Koreans, most of whom had migrated to Japan from the southern half of the Korean peninsula in colonial times, but their numbers included 6,730 Japanese citizens.18

In colonial times, more than two million Koreans had migrated from the Korean peninsula to Japan under conditions which involved varying degrees of freedom and coercion. The vast majority – more than 95% – came from the southern half of the Korean peninsula. After the war, the majority were repatriated to Korea – including two groups, with a total of 351 people, who were officially repatriated to the Soviet occupied northern half of the peninsula by the Japanese government in 1947.19 The 600,000-700,000 Koreans who remained in Japan constituted the country’s largest ethnic minority, and in the 1950s and early 1960s Zainichi Koreans [Koreans in Japan] lived in a situation of legal and social insecurity, and often in deep poverty. Most had entered Japan in colonial times, when they had legally been “Japanese subjects”, but at the end of the Allied Occupation their Japanese nationality had been unilaterally rescinded, and they were left with tenuous legal residence rights, no automatic right to re-entry if they left Japan, and no right to bring relatives from Korea to join them in Japan. Facing uncertain residence status, lack of access to welfare, limited educational and job opportunities and ethnic discrimination in Japan, tens of thousands of Zainichi Koreans [Korean residents in Japan] were persuaded that a better future awaited them in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

The Japanese citizens who took part in this mass migration fell into several categories. Some were wives (or, more occasionally, husbands) of Zainichi Koreans. Others were Koreans who had acquired Japanese nationality (a process that was uncommon but not impossible before the 1960s). The largest number, however, seem to have been children of mixed marriages or de facto partnerships. Under the law of that time, children of a Korean man and a Japanese woman would be considered “Korean” if the couple was officially married, but “Japanese” if they were not. Red Cross figures from the 1964 show that some 6,300 Japanese citizens had joined the migration to North Korea by that date, just over half of whom were children born since 1950. Of those born before 1950, about 20% were men and 80% women. The oldest were ten men and twenty-five women born in the nineteenth century, and thus at least in their sixties by the time they migrated to North Korea.20

I have written at length about the repatriation project elsewhere.21 Here, therefore, I shall discuss its outlines relatively briefly (introducing some further recently declassified material on the topic), as a basis for emphasizing aspects of the huge ongoing human legacy of this project. Contrary to the demonic images of North Korea which flourish in the Japanese media today, the “repatriation” story provides a reminder of the complex and tangled connections which bind these two neighbouring countries together. In Japan today there are tens of thousands of people who have relatives living in North Korea. Many of these divided families keep in touch across the border, and those in Japan often struggle to send money and goods to those in the DPRK (a process made difficult if not impossible by the current economic sanctions).

The discrimination and uncertainty facing Koreans in Japan help to explain the enthusiasm which greeted the plan to assist Zainichi Koreans to “repatriate” to North Korea: a plan first publicly announced by North Korean leader Kim Il-sung in September 1958. After a widespread propaganda campaign and mass demonstrations by the North Korean-affiliated General Association of Korean Residents in Japan [Sōren in Japanese; Chongryun in Korean], the Japanese government on 13 February 1959, declared its willingness to support the scheme, and called on the International Committee of the Red Cross to confirm that the migrants were leaving Japan of their own free will.

But, behind the public face of this “humanitarian” project, lay years of secret political maneuvers. Key members of the ruling Japanese Liberal Democratic Party and the bureaucracy had, since 1955, repeatedly made contact with North Korea via the Red Cross in an effort to persuade the (initially reluctant) North Korean government to initiate just such a scheme. Documents that have recently come to light reveal further details of the complex politics of the “repatriation”. Among these documents is a declassified Japanese government report showing that as early as 1955, Japan’s Foreign Ministry had already drawn up a secret draft plan for a mass “return” of Koreans to North Korea. The plan specifically targeted poor and unemployed members of the ethnic minority (who were seen as a burden on the welfare budget and as a potential security threat) as well as those interned in Ōmura Immigration Detention Center as illegal migrants.22 The Foreign Ministry draft plan proposed that the mass exodus to North Korea should be overseen by the Japan Red Cross, who (the Ministry stated) was to “use Sōren as its partner and request that organization’s cooperation in the above matters.” The Ministry proposed that the Japan Red Cross and Sōren should enter into a written contract “to confirm the correct conduct of each item of business” related to the mass repatriation.

Two envoys from the International Committee of the Red Cross who traveled to Japan the following year to discuss the secret scheme with the relevant government ministers discovered from their discussions that

the Japanese government wishes, for financial reasons and for reasons of security to terminate the stay [in Japan] of about 60,000 Koreans living in its territory… Some of these foreigners are interned, and the authorities in Tokyo wish to suspend the subsidies which they disburse for their subsistence. Moreover, some Koreans are followers of communism, and their presence threatens to cause trouble in Japan.23

The Japanese authorities, however, realized that this scheme was sure to evoke massive opposition from the Republic of Korea (ROK – South Korea). They also knew that the US attitude towards a mass migration from the “Free World” to communist North Korea at the height of the Cold War was likely to be ambivalent at best. There was, therefore, a good deal of internal debate about the repatriation within the Japanese political and bureaucratic elite.24 Meanwhile, the Japan Red Cross (with the backing of senior government officials) had been encouraged to prevail upon the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to be an intermediary, and to conduct a “confirmation of free will” which would give this mass movement of people international respectability. The ICRC, though at first deeply suspicious of the project, was eventually (after an extraordinary campaign of secret worldwide lobbying by the Japan Red Cross and Ministry of Foreign Affairs) persuaded to take on the task. By this time, the government of the DPRK had (in mid-1958) enthusiastically embraced the scheme, apparently seeing it as a source of labour power, and as a factor which might improve relations between Japan and North Korea while destabilizing relations between Japan, South Korea and the United States. Eventually, after months of drawn-out negotiations in Geneva, an agreement on the repatriation was signed in Calcutta in August 1959, and the first repatriation ship left the Japanese port of Niigata bound for Cheongjin in North Korea on 14 December 1959.25

For the tens of thousands who made the journey from Japan to North Korea in the early years of the scheme, the route to the DPRK began at local government offices all over Japan, where counters were set up to register applicants for the “repatriation project”. Although the process was officially supposed to be run by the Red Cross, in fact it was controlled by local government officials and by Sōren, who assisted migrants with their applications and organized them into groups for the journey to North Korea. During the ICRC-supervised “confirmation of free will”, each migrant family had a face-to-face meeting with Swiss officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross, who were supposed to determine that their departure from Japan was really voluntary. For the migrants I have spoken to, however, this supposedly crucial meeting with the Red Cross was an event which barely registered in their consciousness. The interview was over in a few minutes and by the time it took place, they had gone much too far to turn back.

There is an important feature of this process that has been attested to by many participants in the “repatriation” and their relatives: Japanese wives going to North Korea were told they would be allowed to make a return visit to Japan after three years. Interestingly, the voluminous Red Cross documentation on the repatriation project makes no mention at all of this promise, which seems to have originated with Sōren. However, given the very close cooperation between Sōren, local governments and the Red Cross (as well as the fact that Sōren had been deeply infiltrated by police informers), it is inconceivable that Red Cross and government officials were unaware of it.

Newly-arrived Korean children from Japan in the DPRK, as depicted in a North Korean publication

On their arrival in North Korea, the migrants were provided by the DPRK government with one month’s accommodation in reception centers, where they received political education and were taken on tours of local factories and cultural sites. Then they were dispersed around the country to jobs in farms, offices, factories or mines, with little regard to their personal wishes. Many were shocked to discover the poverty of the country to which they had come. In 1966, a North Korean official who had been responsible for looking after the migrants from Japan on their arrival, but subsequently defected to South Korea, told the ICRC that “the first reaction of the repatriates is generally disillusionment”, going on to add: “it is painful to witness the disillusionment of the returnees. It is accompanied by rage and words of insult towards the Red Cross and towards the ‘humanitarianism’ of which it always speaks, and which does nothing but send them down the slope to a miserable country and a miserable situation.”26

One result of the repatriation was that a large number of Korean families in Japan became divided, with some relatives resettling in North Korea and others remaining in Japan. The repatriation thus forged a deep and enduring social link between Japan and the DPRK, but it was a link filled with suffering, with those in North Korea unable to communicate freely with their relatives in Japan, and those remaining in Japan often feeling deeply anxious at the fate of those who had left. A particularly disturbing aspect of the repatriation story is the fact that the Japanese government and Red Cross became aware within the first year of the scheme that many “returnees” to the DPRK were facing severe poverty and hardship on their arrival.27 Indeed, by 1961 the government was actually quoting letters sent by “returnees” to their relatives in Japan in its intelligence assessments to demonstrate the parlous state of the North Korean economy.28 Yet neither the Japanese government nor the Red Cross nor Sōren did anything to stop or slow the scheme, or to warn departing Koreans of the fate that awaited them.

If economic and political conditions had later improved, then the memories of that first shock of arrival might have faded. But in fact, things grew worse. The “returnees” from Japan came to be regarded by the North Korean government as unreliable citizens or (worse still) as spies. Many were “sent over the mountains”: an ominous phrase which can mean anything from being sent to work in a remote and impoverished village to being incarcerated in one of North Korea’s expanding labour camps.

Until the 1970s, it was almost impossible for Koreans who remained in Japan to visit their relatives in the DPRK: between 1963 and 1971, just 24 Zainichi Koreans, all of them aged over fifty, were given re-entry permits allowing them to visit ancestral graves or ageing relatives in North Korea and return to Japan.29 During the 1970s Japan did move to ease some of the restrictions on visits to North Korea by Zainichi Koreans,30 and in September 1971 the Mangyongbong, a North Korean cargo and passenger ship made its maiden voyage between Wonsan and Niigata, initiating a regular ferry link between the two countries.31 In the 1990s this was replaced by a new vessel, the Mangyongbong 92, but, following the DPRK’s nuclear test in 2006, the ship was banned from entering Japanese ports as part of Japan’s sanctions. In recent years, the general mood of fear and hostility towards North Korea has made it particularly difficult for Koreans with family links to the DPRK to maintain those connections, and ironically even means that the small number of former “returnees” who have managed to escape North Korea as refugees and return to Japan since the 1990s find it necessary to conceal their backgrounds for fear of attracting suspicion and discrimination.

The ferry Mangyongbong 92, lying idle in the North Korean port of Wonsan, May 2009

The “Free Movement of People”

From the North Korean government’s perspective, one reason for accepting a large influx of “returning” Zainichi Koreans was the belief that the repatriation would help to strengthen political, economic and social ties with Japan. And indeed, the first years of the repatriation coincided with a noticeable increase in trade between Japan and the DPRK. On 1 April 1961 Japan officially lifted its ban on trade with North Korea, and around the same time, the first cargo shipping service between the two countries was opened.32 However, it seems clear that key proponents of the “repatriation” in the Japanese government, notably Kishi Nobusuke (who was Prime Minister at the time of the signing of the Calcutta Accord) had no intention of moving towards normalization of relations with North Korea, but rather planned to resume normalization talks exclusively with South Korea as soon as a substantial number of Koreans had departed to the DPRK. Indeed, negotiations with South Korea were resumed in earnest from 1961, leading to the signing of a Treaty of Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) in 1965 – a step which resulted in a renewed chill in relations between Japan and the North.

Meanwhile, as trading links between Japan and North Korea developed during the early 1960s, the DPRK had pressed the Japanese government to ease restrictions on the entry of North Koreans to Japan, and at the beginning of 1963 embarked on a campaign to promote the “free movement of people” between the two countries. Given the tight restrictions that existed on movement even between one district of North Korea and another, let alone across national borders, the term “free movement of people” can hardly be taken at face value. However, it does seem clear that the DPRK hoped to open the way to fairly substantial flows of travel between the two countries, including opportunities for relatives in Japan to visit “returnees” in North Korea, and for “returnees”, particularly Japanese wives who had come to North Korea with their husbands, to travel to Japan. It is worth noting that the “free movement” campaign started just three years after the beginning of the repatriation process. It seems likely that Sōren hoped the campaign would make it possible to fulfill the promise to Japanese wives of repatriates that they would be allowed home visits after three years. Conversely, the North Koreans may also have hoped to use the plight of Japanese wives in North Korea as ammunition in pushing the case for expanded travel between the two countries.

The Japanese response to the “free movement” campaign, however, was very cautious, with the government merely agreeing to treat requests for entry by North Korean business visitors on a “case-by-case” basis.33 In general, while the Japanese government did allow a growing number of Japanese businesspeople to travel to the DPRK, it was reluctant to allow the entry of North Koreans, because it feared the reaction from South Korea, and was concerned that North Koreans might use their visits for intelligence gathering or ideological purposes. While the North Korean government urged the creation of channels to allow Japanese who had participated in the “repatriation” to make return visits to Japan, the Japanese government resisted, amongst other things expressing doubts “that many North Korean repatriates would actually want such permits”, and suspecting that “North Korea is seeking the concession as a political tactic.”34

The Fate of the “Japanese Wives”

During the 1990s, however, the issue of cross-border movement between Japan and North Korea resurfaced in the context of new signs of a possible thaw in Japan-DPRK relations. In 1990, a three-party declaration was signed in Pyongyang by a group of politicians from the North Korean Workers’ Party, Japan’s ruling LDP and the opposition Japan Socialist Party, and this opened the way to negotiations on a normalization of relations. By this time, many of the Japanese citizens who had migrated to North Korea as part of the repatriation project were ageing, and in some cases their families in Japan were desperately lobbying the government to secure an opportunity for a reunion. The Japanese government, having failed to respond to North Korean initiatives on “free movement” in the 1960s, now began to press North Korea for details of the fate of Japanese nationals in the DPRK, and to call on North Korea to allow home visits by Japanese wives of “returnees”. In 1993, when North Korea criticized Japan before the United Nations Committee on Human Rights for its failure to address the “Comfort Women” issue (the plight of Korean and other women subjected to institutionalized sexual abuse by the Japanese military during the colonial period), Japan responded by criticizing North Korea for its failure to provide information on the “Japanese wives”.35

The issue of Japanese “returnees” to North Korea, however, also raised some delicate questions of nationality, ethnicity and gender.36 Both the Japanese government and the media repeatedly referred to this issue as the problem of “the Japanese wives” [Nihonjinzuma], and the Japanese Ministry of Justice in the early 1990s estimated the number of these wives at around 1,800. But, as we have seen, the number of Japanese nationals who had migrated to North Korea under the repatriation program was in fact over 6,000. The definition of the issue as being one of “Japanese wives” meant that other Japanese nationals who had gone to North Korea (husbands, children, adopted family members, naturalized Japanese nationals) were excluded, though the grounds for this exclusion were never made explicit. The focus on the Japanese wives, of course, also excluded from consideration the Zainichi Korean returnees who did not possess Japanese nationality, but some of whom were undoubtedly also very eager to be reunited with ageing relatives in Japan and to revisit the places where they had been born and brought up.

Despite these limitations, negotiations on the “Japanese wives” issue did provide an opportunity for Japanese local government and NGO officials to travel to Pyongyang and meet their North Korean counterparts, thus gradually broadening the scope of communications between the two countries. A particularly important part in these discussions was played by the Japanese and North Korean Red Cross Societies, who (as we have seen) played central roles in the original mass migration. On 10 September 1997, the two societies reached agreement on the “Japanese wives” issue, and one month later (and unmistakably as a quid pro quo) the Japanese government announced its major commitment of aid to famine-stricken North Korea via the World Food Program and ICRC.37

Members of the first group of “Japanese Wives” to be allowed to make a visit to Japan speak at a press conference at Narita Airport, Nov. 1997

The first visit by fifteen Japanese wives from the DPRK took place in November 1997. The women stayed for a week, and most were able to return to their old hometowns for emotional reunions with friends and families. A second group of twelve arrived in January 1998, and further group visits were planned. But by then, the atmosphere of Japan-North Korea relations was again souring. This time, the central problem was the growing suspicion in Japan about the abductions. In the late 1990s, the DPRK heatedly denied the accusation that it had been responsible for any kidnappings, and sought to turn the tables on Japan by criticizing its government for seeking to exclude Japanese wives who had renounced their Japanese nationality from taking part in the group visits home. As these acrimonious exchanges intensified, the third planned visit by Japanese wives was canceled, to the bitter disappointment of some relatives of proposed participants.38 More than ten years on, the visits have yet to be revived.

The Terakoshi Case

As the issue of the kidnappings began to be widely reported in the Japanese media, another story attracted growing attention: the strange disappearance, and later re-appearance in North Korea, of three members of the Terakoshi family, a fishing family from Ishikawa Prefecture in western Japan.39 Subsequently the story of the Terakoshis, and particularly the difficult situation of Terakoshi Takeshi, who remains in North Korea today, was edged out of the headlines by the mass of reporting on the stories of the abductees. But the Terakoshi case is worth examining in detail, both because of ongoing issues related to the situation of this Japanese resident in the DPRK, and because of the light the story sheds on the complexities of the human and political relationship between Japan and North Korea.

On 10 May 1963, at a time when the outflow of Korean “returnees” from Japan to North Korea was slowing to a trickle and the “free movement” campaign was gathering momentum, a small boat set out on a routine fishing trip from the port of Takahama on the Noto Peninsula in Ishikawa Prefecture. On board were two brothers, Terakoshi Shōji, then aged 36 and Sotoo, aged 24, the second and fourth sons of a large family who fished and farmed in Takahama. They were accompanied by their nephew Takeshi, the thirteen-year-old son of their oldest brother.

The boat failed to return that evening, and the following day it was found drifting and empty, with marks of a collision on one side. The weather had been calm and there was no obvious explanation for the mishap. After a week of fruitless searching, it was assumed that the brothers and their nephew had been accidentally drowned, and a memorial ceremony was held.

Terakoshi Tomoe, the mother of teenager Takeshi, describes the mental anguish she suffered after her son’s disappearance as follows:

I hunted for Takeshi everywhere. I couldn’t believe that he was dead. In the end I went to consult a fortune-teller, who told me that Takeshi had drowned, and added, “you have one daughter, haven’t you? The Water God [mizu no kamisama] is going to come and take your daughter too”.

I cried out, “oh no, help me, help me!”

The fortune-teller said, “I’ll help you, but you must go to visit this temple”.

So I promised to go to the temple by the very first train the next morning – the temple was about one hour away by train. But when I got back home and told my mother-in-law what the fortune-teller had said, she wouldn’t give me any money for the train fare. I only had an allowance of 500 yen a month, and I couldn’t afford the fare. So I had to give up the idea of going to the temple. I just thought, “Takeshi is dead, and if I lose my daughter too, I’ll hang myself.

For more than a year, I would say to the schoolteachers, “don’t let my daughter go swimming. Don’t take her on school outings. Don’t even let her cross a bridge when it’s raining. The Water God wants to take her away.”

I lost so much weight, all my friends told me that I was becoming neurotic. But then time passed, and nothing happened to my daughter.

She adds with a wry laugh, “You should never, never believe what you are told by fortune-tellers.”40

For, twenty-four years after Shōji, Sotoo and Takeshi disappeared, and many years after all their family had given them up for dead, Tomoe received a phone call from her sister-in-law with astonishing news. A letter from Sotoo had arrived, posted in North Korea. In it, Sotoo stated briefly and with little explanation that he and his brother and nephew had ended up living in the DPRK. A second letter soon after explained that Shōji had died of a heart attack several years after their arrival in North Korea.

1987, the year when the letter arrived, was almost ten years before the abduction issue became widely known in Japan, and the media and authorities at first showed little interest in the Terakoshis’ story. Neither the local police, nor Sōren, nor the Red Cross showed any inclination to help, and the family was left facing the huge problem of finding a way to be reunited with their lost relatives. Eventually, the case was taken up by a local city councilor who brought it to the attention of the prefectural and national governments. It was only then that the story was reported in the Chūnichi newspaper, and soon after, Shimazaki Yuzuru, a senior Japan Socialist Party politician, helped to arrange a visit to North Korea by Tomoe and her husband Tazaemon, to meet their son for the first time in a quarter of a century.

As is common in these cases, Tomoe and Tazaemon, who were both longing for and deeply anxious about the reunion, were required first to go on a series of obligatory tours around North Korean landmarks. They were almost beginning to despair of seeing their son at all, and fearing that the North Koreans would produce an imposter in his place, when on their third day in North Korea (as Tomoe recalls),

the guide suddenly said, “Right, Mr. and Mrs. Terakoshi, now you’re going to meet your son.”

They took us to the Koryo Hotel. My legs we’re shaking, and I had no idea where I was going. There were all sorts of people there, and I didn’t know who was who. I called out “Takeshi”, but I didn’t know who to speak to. Then Sotoo said, “sister!”

I recognized Sotoo, but I still didn’t know which one was Takeshi. I sat down and they brought him and said, “this is Takeshi,” and then I couldn’t stop crying.

I didn’t recognize him. The last time I’d seen him he’d been thirteen, with a round face and a shaven head, and now he was 37 or 38 and really tall. But he had a scar on his forehead where it had been hit with a bat when he was a child, and when I saw the scar I knew this was my son.

Long after that first meeting, Takeshi told us that he had actually already seen us the previous day. A friend had let him know that his mother and father had come from Japan, and would be visiting the Juche Tower [a famous Pyongyang landmark] at 10 a.m., so he had gone and hidden himself behind a pillar and seen us. Of course he couldn’t say anything at that time, but he had recognized us right away.41

After the reunion in Pyongyang, Socialist Party politician Shimazaki published a pamphlet which repeated the official North Korean explanation for the Terakoshis’ arrival in the DPRK: their fishing boat had lost engine power and drifted off course. During the night, it had collided with a North Korean vessel whose crew had rescued the fishermen and taken them to North Korea.

Tomoe learnt that, since their arrival in North Korea, Terakoshi Sotoo and Takeshi had been living in the town of Kusung, where Takeshi had attended school, and later gone to work in a machine factory. Sotoo had married a “returnee” from Japan, but Takeshi, whose Korean had become perfect, married a local North Korean woman and had three children – two sons and a daughter. Until Takeshi’s parents came to Pyongyang to visit him, neither his wife nor their children nor any of their friends had the least idea that he was Japanese. It was only when they went to Pyongyang to meet Tomoe and Tazaemon that, for the first time, Takeshi revealed the secret of his background to his astonished wife.

In 1997, Takeshi’s parents succeeded in restoring their son’s Japanese family registration [koseki], which had been annulled when he was declared dead. At that point, the North Korean authorities allowed Takeshi to move permanently to Pyongyang, where he was given various privileges. He now lives in a spacious apartment in central Pyongyang, in a block which is occupied by families in elite positions in the North Korean political system. Having spent the major share of his life in North Korea, he speaks Korean more easily than Japanese, and goes by the Korean name Kim Yeong-Ho. His children, who only know life in the DPRK, have done quite well: his second son has a degree from a prestigious university and his daughter is a kindergarten teacher. Since the first visit in 1987, his mother has visited him more than fifty times. Takeshi’s father Tazaemon actually moved to Pyongyang in 2001 to spend the last years of his life with his son.42 He died and is buried in North Korea. Meanwhile, Terakoshi Sotoo had died of lung cancer in 1994, leaving Takeshi as the only one of the original three family members still living in the DPRK.

In October 2002, immediately before the return of the five abductees to Japan, Terakoshi Takeshi was allowed to make a visit to his home country. He was, however, treated quite differently from the returning abductees. While the abductees were met by officials of the Japanese government, and their arrival was given saturation coverage by the media, the management of Terakoshi Takeshi’s visit was left to Sōren, and media coverage was muted. All of this reflects a deep ambivalence on the part of the Japanese government towards the Terakoshi case. The complexities and ambiguities of the case have in fact turned the Terakoshi family into a “divided family” in multiple senses of the word: not only is Tomoe physically separated from her son, but the family has become politically divided over the issue of abduction.

In the second half of the 1990s, when the abduction stories were first widely reported in the Japanese media, the Terakoshi case received considerable media prominence, and Terakoshi Takeshi’s plight was often linked to that of Yokota Megumi, who was the same age as Takeshi when she was kidnapped and taken to North Korea.43 The connection was reinforced when Ahn Myung-Jin, a North Korean agent who had been engaged in clandestine activities, but had later defected to South Korea, published an account of the Terakoshi case that starkly contradicted the official North Korean version.44 According to Ahn’s account, the Japanese fishermen had witnessed activities being carried out by a North Korean spy vessel. The North Korean seamen, fearing that the Terakoshis would report what they had seen, seized them and sank their boat. During the struggle, Ahn reported, Terakoshi Shōji was shot dead and his body was dumped at sea.

Terakoshi Shōji’s son Akio and other members of his family believe this version of events, and have insisted that Shōji, Sotoo and Takeshi be included on the Japanese government’s list of abductees.45 On the other hand, Terakoshi Takeshi himself firmly denies that he was abducted, and has given detailed descriptions of his life with Shōji in North Korea, and of Shōji’s death from a heart attack in 1968. His mother Tomoe, although uncertain exactly how to explain the disappearance of the fishermen, also questions Ahn Myung-Jin’s story. As she points out, Ahn was only a child in 1963, when the events he described occurred, and so his account is at best a second-hand story heard long after the event. Ahn’s statement that the North Koreans sank the Terakoshis’ fishing boat is also at odds with the fact that the boat was found floating after its occupants’ disappearance.

It is worth noting that all the other officially recognized abductions took place in a relatively limited space of time, between 1977 and the early 1980s, and seem to have been part of a deliberate and bizarre, but relatively short-lived, North Korean policy. The Terakoshi case, which occurred more than a decade earlier, does not fit this pattern. On the other hand, if the fishermen were really rescued by North Korean sailors, this leaves unanswered a large and obvious question: why were they not sent home or allowed to contact their family once they reached North Korea?

During Takeshi’s return visit to Japan in 2002, the children of Terakoshi Shōji went public with their concerns, appearing on a popular TV program to demand an investigation of their relatives’ fate, and soon after they joined the Abductee Family Association. They argue that Shōji, Sotoo and Takeshi were the victims of abduction (and, in Shōji’s case, murder) by the North Korean state, and call for a robust response from the Japanese government. For Terakoshi Tomoe, on the other hand, the issue is different. Her son remains living in North Korea, and has not been allowed to visit Japan again since his short trip in 2002. As Tomoe grows older, it becomes harder and harder for her to make frequent visits to North Korea. Political tensions following the recent North Korean missile and nuclear tests have also made travel to North Korea by Japanese more difficult to arrange. Meanwhile, despite his relatively privileged situation, Takeshi, as a Japanese citizen living in North Korea, is always in an uncertain and vulnerable position. From Tomoe’s perspective, then, the main aim is persuade the Japanese and North Korean governments to reach an agreement that will protect Takeshi’s rights, and allow him to make home visits to Japan.

For decades, Terakoshi Tomoe has pursued this aim with great tenacity and determination, lobbying officials and politicians in the face of considerable opposition and criticism, particularly from some members of the abductee support groups. To her, the issue is not one of politics, but simply of a mother’s love for her child. She speaks with passion of her sense of remorse at having been unable to spend as much time as she would have liked with Takeshi when he was a small child: because of her own health problems and the difficulties of bringing up her son within a large extended family, Tomoe often had to send Takeshi away to stay with his maternal grandparents. This, however, merely strengthens her determination to make things up by committing herself wholeheartedly to protecting the rights and well-being of her son. She would also like to be able to bring together Shōji’s sons and Takeshi (who have never been reunited since the events of 1963), so that her nephews can hear and discuss Takeshi’s account of the events that brought him to North Korea.

Terakoshi Tomoe, photographed in June 2009

Above all, though, Tomoe argues that in order to resolve the personal sufferings caused by the freezing of Japan-North Korea relations – the sufferings not only of herself and her son, but also of the abductee families, the “Japanese wives” and the Korean families divided by the repatriation – the basic principles of human communication should be applied to relations between the two nations:

When I visit the Foreign Ministry, I say to the officials, “Of course North Korea’s in the wrong; but Japan is wrong too,” and they agree with me. However bad North Korea may be, I don’t think it’s completely bad. There must be some good things there.

If people can talk together, they can try to discover the good in each other. At any rate, that’s what I’ve learnt from my own life. Whatever the problem, it is best to sit down and talk about it together.

When I was at primary school, I learnt a song. It’s a song from the Russo-Japanese War, about the time when the Japanese and Russian commanders met for talks at Port Arthur. It goes:

“if you speak to one another with an open heart,

yesterday’s enemy is tomorrow’s friend.”

No one seems to quote those words today. Today it’s just “yesterday’s enemy is an even worse enemy tomorrow”. But I really like that song.46

With a new government in power in Japan and renewed possibilities of dialogue between North Korea and its neighbours, perhaps Japanese officials will again sit down at the same table to talk. If they do so, it is to be hoped that their discussion will not focus exclusively on abductions, missiles and nuclear weapons, but will also address the human side of Japan-North Korea relations in broader terms – helping to ease the sufferings both of Japanese in North Korea and of Koreans in Japan whose lives have been fractured by sixty years of Cold War conflict.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History at the Australian National University. She is the author of Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. Her most recent book, Borderline Japan: Foreigners and Frontier Controls in the Postwar Era is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “The Forgotten Japanese in North Korea: Beyond the Politics of Abduction,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 43-2-09, October 26, 2009.

See also the following relevant articles:

John Feffer, “North Korea, Japan and the Abduction Narrative of Charles Robert Jenkins”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 2 July 2008.

Gavan McCormack, “Disputed Bones: Japan, North Korea and the ‘Nature’ Controversy”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 18 April 2005.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “The Forgotten Victims of the North Korean Crisis”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 15 March 2007

Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “Japanese War Orphans and the Challenges of Repatriation in East Asia”, The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 13 August 2006.

Notes

1 Rachi Higaisha Taisaku Honbu, “Rachi Higaisha: Torawareta Shōjotachi” (50 second video advertisement), link.

2 Particular debate surrounds the return to Japan of the “ashes” of kidnap victim Yokota Megumi. North Korea returned what it claimed were part of the remains of Yokota. The Japanese government has insisted that DNA testing shows that these are not Yokota’s remains, and has accused the DPRK of fraud. Independent scientific examination of the issue, however, has cast doubts on the capacity of the Japanese testing procedures to determine the origins of the remains. For a discussion of this issue, see Gavan McCormack, “Disputed Bones: Japan, North Korea and the ‘Nature’ Controversy”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 18 April 2005.

3 The Allied occupiers estimated the number of Japanese to be repatriated from northern Korea in August 1945 at 322,500, compared with 594,800 from southern Korea; see GHQ SCAP, Reports of General MacArthur – MacArthur in Japan: The Occupation: Military Phase (Volume I supplement), Washington, US Army Center of Military History, facsimile reprint, 1994, p. 148.

4 Asahi Shinbun, 23 April 1956.

5 Letter from Inoue Masutarō to Léopold Boissier, ICRC, 1 May 1956, in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 055-001.

6 See letter from Inoue Masutarō, Director of Foreign Affairs Department, Japan Red Cross Society, published in Nippon Times, 2 November 1955.

7 Telegram from League of Red Cross Societies to Red Cross Society, DPRK, 6 January 1954, in Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (hereafter ICRC Archives), B AG 232 055-001, Ressortissants japonais en Corée-du-Nord, 22.01.1954-11.05.1956.

8 Telegram from Red Cross Society DPRK to League of Red Cross Societies, 6 February 1954, in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 055-001.

9 See Australian Embassy Tokyo, Weekly Situation Report no. 21, “Relations with North Korea”, in Australian National Archives, series no. 1838, control symbol 1303/11/91 Part 1, Japan – Relations with North Korea.

10 On the story of Zanryū Nihonjin in China, see Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “Japanese War Orphans and the Challenges of Repatriation in East Asia”, The Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 13 August 2006.

11 Letter from Harry Angst to ICRC, 12 March 1956, in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 055-001.

12 Letter from Inoue, Nippon Times, 2 November 1955.

13 Letter from Angst to ICRC, 12 March 1956; see also Asahi Shinbun, 22 April 1956 (evening edition).

14 Asahi Shinbun, 31 May 1956.

15 Asahi Shinbun, 22 April 1956 (evening edition)

16 “Fukansha wa 800-nin Amari: Senzen, Senchū Kaigai ni ita Nihonjin, Sengo no Nihonhei”, Aera, 4 July 1994, p. 46.

17 Asahi Shinbun 11 January 2009. Murayama Hisako and her husband had run an orchard in the northern half of Korea in colonial times. At the end of the war, she was separated from her husband and two daughters, but in 1952 she learnt that her elder daugher Setsuko was still alive in Cheongjin. Murayama Hisako had been lobbying the Japanese government and other groups ever since to help her find a way to see Setsuko again. In the late 1990s, Murayama was given information suggesting that Setsuko might be included in the fourth group of “Japanese wives” to visit Japan. However, because of tensions over the abduction issue, this visit never took place. Murayama Hisako died on 2 December 2008. Setsuko is now 79.

18 Kim Yeong-Dal and Takayanagi Toshio eds., Kita Chōsen Kikoku Jigyō Kankei Shiryōshū, Tokyo, Shinkansha, 1995, p. 341.

19 Inoue Masutarō, “Zainichi Chōsenjin Kikoku Mondai no Shinsō” (1956) reproduced in Kim Yeong-Dal and Takayanagi Toshio eds., Kita Chōsen Kikoku Jigyō Kankei Shiryōshū, Tokyo, Shinkansha, 1995, pp. 9-28, citation from p. 14.

20 Of the 6,331 Japanese nationals who had left Japan for the DPRK as of May 1964, 3,318 (1,789 boys and 1,531 girls) had been born after 1950. Of the 3,013 born before 1950, 659 were men and 2,354 women. See Immigration Control Bureau, Justice Ministry, “Monthly Report on Repatriation to North Korea, no. 53, 31 May 1964”, (English translation) in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 105-030.01, Monthly reports on the repatriation to North Korea, 31.03.1961-31.12.1964.

21 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2007; see also “The Forgotten Victims of the North Korean Crisis”, Japan Focus, 15 March 2007.

22 Hokusen [sic] e no Kikan Kibōsha no Sōkan Shori Hōshin [Plan for Arranging the Sending to North Korea of those who wish to be Repatriated. The term “Hokusen” is a discriminatory abbreviation for North Korea]. This report is reproduced in Nikkan Kokkō Seijōka Kōshō no Kiroku Sōsetsu Vol. 6 – Zainichi Chōsenjin no Kikan Mondai to Kikan Kyōtei no Teiketsu, document 126 of the third release of official material pertaining to Japan-ROK relations, released 16 November 2007, pp.44-53, link (accessed 23 December 2007); see particularly pp. 49-50.

23 Minutes of meeting, Conseil de la Presidence, Tuesday 19 June 1956, p. 6, in ICRC Archives, file B AG 251 075-002, Mission de William H. Michel et d’Eugène de Weck, du 2 mars au 27 juillet 1956, visites aux sociétés nationals et problème du rapatriement des civils la Corée et le Japon, première partie, 01.03.1956-06.08.1956.

24 For a discussion of these internal political divisions, see for example letter from Inoue Masutarō to Léopold Boissier, 31 May 1957, in Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, (ICRC Archives), B AG 232 105-005.01, Généralités: Correspondance avec les Sociétés nationales de Japon, de la République démocratique populaire de Corée et de la République de Corée au sujet du rapatriement des Coréens du Japon et du retour des pêcheurs Japonais détenus en République de Corée, 01.08.1956-29.12.1957.

25 For a more detailed discussion of these negotiations, see Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea, Ch. 15.

26 Letter from Testuz to Maunoir, 4 Aug. 1966, ICRC Archives B AG, 232 105-035; Japanese communication, Ms. Y., returnee-refugee, Tokyo, 3 June 2005.

27 See memo “Re- Call on Messrs. Satoshi Kurisaka, Chief, Nobuo Miyamoto, Section 2 – Koreans, of the Public Peace Investigation Bureau, Hyogo District, 24 August 1960”, attached to Zeller to Durand, 4 September 1960, in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 105-017, Problème du rapatriement des Coréens du Japon, dossier XIV: Generalités concernant l’année 1960, deuxième partie. 12.04.1960-12.12.1960.

28 See ‘Information for Judgment of North Korean Situation’, English translation of an intelligence by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, sent to the British Foreign Office by British Embassy, Tokyo, 2 August 1961, in British National Archives, file no. FO 371-. It is not clear how the Japanese government obtained copies of these letters.

29 Telegram from Australian Embassy, Tokyo, to Department of External Affairs, Canberra, 31 August 1971, in Australian National Archives, series no. A1838, control symbol 3125/11/87 Part 1, “North Korea – Relations with Japan”.

30 Kim Chan-Jung, Chōsen Sōren, Tokyo, Shinchō Shinsho, 2004, p. 134.

31 From 1959 to 1967, “returnees” had traveled on Soviet ships loaned to the North Korean Red Cross.

32 Daily Yomiuri [English edition], 7 April 1961.

33 Asahi Shinbun, (evening edition), 10 August 1965.

34 Letter from A. B. Jamieson, Australian Embassy Tokyo, to Secretary, Department of External Affairs, Canberra, “Korea”, 2 July 1966, in Australian National Archives, series no. A1838, control symbol 3103/11/91 Part 1, Japan, Relations with North Korea; see also memo from Kiuchi Risaburō, Vice-Director of Foreign Affairs Department, Japan Red Cross Society, to Michel Testuz, ICRC representative in Tokyo, “Information sur la question du ‘libre passage’ entre Japon et la Corée-du-nord”, 9 April 1965, in ICRC Archives BAG 251 105-009.02, Correspondence reçu du 12 juin 1962 au 21 janvier 1966, 12.06.1962-21.01.1966.

35 Asahi Shinbun, 7 March 1993.

36 See Kang Sang-Jung, “‘Satogaeri’ ga Nihon ni tsukitsukeru mono”, Asahi Shinbun, 15 October 1997.

37 On the link between food aid and the “Japanese wives” issue, see for example Yomiuri Shinbun (Tokyo edition), 10 September 1997.

38 Asahi Shinbun (evening edition), 8 June 1998

39 Information on the Terakoshi case provided here is derived from an interview with Terakoshi Tomoe, 15 June 2009; Rescuing Abductees Center for Hope (REACH) ed., The Families, electronic book published on the website of REACH, (n.d.), chapter 7; and numerous newspaper articles on the case.

40 Interview with Terakoshi Tomoe, 25 June 2009.

41 Interview with Terakoshi Tomoe, 25 June 2009.

42 Japan Times, 20 August 2002.

43 See for example Chūnichi Shinbun, 12 February 1997, p. 11; Sankei Shinbun, 9 May 1997, p. 29; Hokkoku Tōyama Shinbun, 29 January 1998, p. 32.

44 For further details on Ahn Myung-Jin, see Bradley K. Martin, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty, New York, Thomas Dunne Books, 2004, pp. 535-542.

45 see REACH ed., The Families, op. cit., ch. 7.

46 Interview with Terakoshi Tomoe, 25 June 2009.