Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

Forgotten by Whom?

On 27 May 2009, the government of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK, North Korea) provoked worldwide alarm and protest by announcing that it no longer considered itself bound by the 1953 armistice ending the Korean War. Amongst the mass of western media reports deploring this announcement, however, only a few noted the fact that the armistice has never been signed by the Republic of Korea (ROK, South Korea), because its then President Yi Seungman [Syngman Rhee] did not accept that the war was over, and wanted to go on fighting. The armistice was therefore signed only by some of the belligerents, and, since negotiations on the Korean Peninsula in the UN framework proved abortive and the US and North Korea have not pursued bilateral peace negotiations, there has never been a peace treaty. [1] More than half a century after the ceasefire, Korea remains uneasily divided along the 38th Parallel, one of the world’s most dangerous military flashpoints. Of all the conflicts over history and memory which trouble the Northeast Asian region, this is surely the one most directly linked to contemporary politics: for rival understandings of the unfinished war lie at the heart of continuing political tensions on the Korean Peninsula.

As Sheila Miyoshi Jager asks, “how does one commemorate a war that technically is still not over?” [2] In English language writings, the Korean War is referred to, with almost monotonous regularity, as “the Forgotten War”. This description, however, begs an important question: forgotten by whom? Certainly not by the people of North Korea, where education, propaganda, TV dramas and repeated air-raid drills ensure that the conflict is experienced as an ongoing reality. Nor, I would suggest, have many South Koreans (particularly those of older generations) forgotten the Korean War. The term “Forgotten War”, then, refers largely to an American amnesia, although this amnesia is probably also shared by some of America’s major allies, including Australia, Britain and Japan. (The latter, of course, though not a combatant in the war, was deeply involved in providing bases and material support for the UN forces engaged in the conflict). Or perhaps, as Bruce Cumings has suggested (quoting French literary theorist Pierre Macherey), we should see the silence less as amnesia than as “structured absence”. [3]

The Return of the Past

Even in America, however, frequent recent references to “the Forgotten War” suggest that flashes of irrepressible presence are starting to break through the structured absence. You have to remember something in order to be able to describe it as “forgotten”, and indeed Philip West and Suh Ji-Moon’s collection of essays Remembering the ‘Forgotten War’ is just one of a growing number of works which, over the course of the past decade or so, have examined the production of US amnesia about the Korean conflict. [4] Recent English-language studies have looked at the war in Korean literature, in photography and in Seoul’s War Memorial of Korea, its presence in Korean movies and its general absence from Hollywood box-office hits. [5] Ha Jin’s award-winning novel War Trash has also offered a vivid if contentious evocation of the events of the war, directed at a US audience but written from a Chinese perspective. [6]

In US popular culture itself, there have also signs of the emergence of an uneasy contest of war memories. 2008 saw the release of a movie which I believe to be the first Hollywood blockbuster to acknowledge the dark side of the actions of US troops in the Korean War: Clint Eastwood’s Gran Torino. Eastwood’s central character, Walt Kowalski (played by the director himself), is a Korean War veteran haunted by the cruelties of the war, and particularly by the face of a young enemy soldier whom he killed as the soldier attempted to surrender. The resurfacing of Kowalski’s repressed memories comes a decade after revelations by a team of US journalists about the massacre of Korean civilians at Nogun-Ri, and follows the circulation and debate on the Internet of the BBC’s haunting 2002 documentary “Kill ‘em All: The American Military in Korea”. [7]

On the other hand, and perhaps partly in reaction to these troubling ghosts from the past, 2009 marked the opening (“thanks to a generous gift from Turtle Wax Inc.”) of the initial stage of the first, only and still incomplete national Korean War museum in the United States. Created by a group of war veterans and their supporters, the Korean War National Museum in Springfield, Illinois, sets out to present an unabashedly triumphal vision of the war – “the forgotten victory” – as “the first time that the advance of communism was halted”. [8] The theme of victory is highlighted by the museum’s logo, defiantly focused on a bright red letter V surrounded by a laurel wreath. Images of the planned museum posted on its website show a flowing design of exhibition spaces featuring large photographic panels and life-size reconstructions of villages and dugouts. (See this link)

The museum’s prospectus and its archive of photographs focuses firmly on the US experience of the war, in which, we are told “54,246 soldiers paid the ultimate sacrifice” (a figure which leaves a strange haze of silence around the estimated 3-4 million Korean soldiers and civilians, several hundred thousand Chinese “volunteers”, more than 3,000 soldiers from other countries of the United Nations Command and 120 Soviet pilots who were also killed in the war). The images which illustrate the museum website, however, do include one striking picture of Korean civilian suffering – a picture also featured in China’s Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea (discussed in more detail later in this paper). This is a photograph, taken during the Incheon Landing, of a lone small girl sitting weeping outside what appears to be a bombed factory. On the US museum’s website the photograph is accompanied by the words, “during the war, the American armed forces saved thousands of Korean lives.” [9] In the book I purchased at the Chinese memorial, the same photograph is captioned. “American ruffians of aggression brought extremely serious catastrophe. An unfortunate girl in flames of war crying loudly on the street”. [10] I wonder what became of the little girl, and, if she is still alive, how her memories of war would relate to these divided pronouncements on the meaning of her grief.

Child amid the ruins of the Korean War

In this essay I want to approach the question of contested memories of the Korean War by considering how the conflict is represented in the museums of several key participant nations on the western side of the Pacific: in the War Memorial of Korea in Seoul; the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang; the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea in Dandong, China; and the section of the Australian War Memorial devoted to the Korean War. The names of the museums themselves speak volumes about the contrasting ways in which the war is remembered.

Museum displays can be examined from many perspectives: which historical facts are presented and which are omitted? What narrative of the past does the museum tell? How do its design, layout and use of media engage the attention and emotions of visitors? How do visitors experience past events as they walk through the museum’s halls? What policies and controversies surround the museum’s creation and the evolution of its displays? In order to understand the role that the museum plays in creating contending memories of war, we need also to know something about the place of each museum in public memory. Who visits the museum? Does it present an unquestioned national narrative of the past, or are its displays open to multiple interpretations or challenged by alternative discourses? [11]

Here I have chosen to take a snapshot in time. Although I make some comments about the history of the museums themselves, I focus mainly on examining the images of the Korean War displayed at the time of writing (2009). I am particularly interested in understanding how each museum’s representation of the war influences perceptions of the contemporary crisis on the Korean Peninsula. For this reason, I shall consider how each addresses certain key questions about the origins and consequences of the conflict. What was the background to the outbreak of the Korean War? How did the war start? Who were its heroes, villains and victims? How did the war end? What was its aftermath and what are its implications for the present? To answer these questions involves looking at the factual narratives presented through written information, photos, artifacts, video displays etc. But it is also important to consider the media through which the story is told. How do Korean War museums use design and technology to evoke the experience of the war, particularly for those who have no direct memory of its events?

In the final section of the paper, I shall bring together some reflections on the museums to assess the links between their representations of the past and contested understandings of the present. Here I want to draw again on Cumings’ notion of “structured absence”. An exploration of these museums offers glimpses of the way in which remembering and forgetting are intertwined. Each memorial presents a narrative of the war carefully constructed in response to the complex political, social and cultural context in which the memorial operates. Each narrative, by shining a bright light on certain faces of the war, intensifies the darkness that shrouds other faces. The task, I shall argue, is complicated by these monuments’ ambiguous status as both “memorials” and “museums”. By comparing them, and (metaphorically) laying their conflicting displays side-by-side, can we fill the absences with presence, and discover some pointers to paths which might take us beyond conflict?

The War Memorial of Korea, Seoul

A visit to a museum is always a conversation. As visitors, we arrive with our own memories and preconceptions, and these influence the way in which the museum’s displays speak to us, and the way in which we respond. Sometimes we wander round museums on our own; sometimes in the company of others, whose comments add to the conversation, further affecting the way we see the displays. My perceptions of the War Memorial of Korea, which I visited on a rainy day in May 2009, were influenced by the fact that I had recently completed a short stay in North Korea, and had just come back from a bus trip to the southern side of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) dividing North from South. The bus dropped me off in Itaewon, the area of Seoul next to US Army Garrison Yongsan, which occupies two-and-half square kilometers of city centre. I walked down the long road bisecting the base, bordered by high walls topped by razor wire. This took me directly to a side entrance to the War Memorial of Korea, which stands next door to the base. The wide grass-and-paved area around the museum is full of those outsized weapons of war which cannot be accommodated within the museum itself, and to reach the main entrance I walked under the wing of a vast US B-52 bomber: one of the prize exhibits.

US B-52 bomber exhibited in the grounds of the War Memorial of Korea, Seoul

My perceptions of the War Memorial were therefore slightly different from those of Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Jiyul Kim, whose careful study of this remarkable edifice was written during the presidency of the late Roh Moo-Hyun, at a time when the Sunshine Policy of engagement between North and South was at its height. For Jager and Kim, a key issue was to understand how the Memorial approached its task of commemorating the Korean War from a South Korean perspective while the government was engaged in rapprochement with the enemy: “the problem for South Korea’s leaders”, they wrote, “was how to fashion a narrative of triumph that would leave open possibility for peninsular reconciliation”. [12] After all, as they point out, the Memorial itself is a “post-Cold War” construction, opened in 1994, during the period when then President Roh Tae-Woo was engaged in his “Nordpolitik”, a predecessor to the Sunshine Policy of Presidents Kim Dae-Jung and Roh Moo-Hyun.

Several strategies were used by the Memorial’s designers to weave together the tasks of commemoration and reconciliation. One was to place the Korean War in the broader expanse of national history. Although the largest part of the Memorial is taken up with displays on the 1950-53 conflict (which in South Korea is most often called the 6.25 War, a reference to its starting date of 25 June 1950), the first floor of the main building is occupied by a display on earlier wars, including 13th century struggles with the Mongols and the 16th century Korean victory in the face of Japanese warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s attempted invasion. The emphasis here is overwhelmingly on united national resistance to outside foes. As the opening words of the War Memorial’s English-language guide put it:

Korea is a nation that has been cruelly subjugated by foreign countries throughout much of its history. But despite the rise and fall of native dynasties and foreign suzerains, the Korean people have maintained an independence that dates back to 668 when the Silla Kingdom succeeded in achieving a political union of the country. This achievement provided the basis for the development of Korea as a distinct nation. [13]

This theme of a nation united against foreign threats is carried through into the design of the Korean War Monument at the centre of the Memorial’s main plaza. This massive statue is inspired by the form of an ancient Korean dagger, which is seen (as Jager and Kim note) as a symbol of the “earliest Korean race”. [14] A second symbol of reconciliation is the “Statue of Brothers” standing at one corner of the Memorial precinct. Based on a photograph of two brothers from opposite sides of the Korean War who met on the battlefield, the statue shows a large and muscular South Korean soldier embracing and looking down upon his smaller and frailer North Korean kinsman – thus simultaneously embodying messages of triumph and of reconciliation. [15]

The desire to leave open a path to reconciliation may also explain why the Memorial’s displays on the Korean War contain only fleeting references to massacres or maltreatment of prisoners-of-war by North Korean troops. This is in strong contrast to the rhetoric of earlier South Korean regimes, particularly of the Park Chung-Hee dictatorship, which energetically kept alive the memory of cruelties inflicted on South Koreans by the Northern “Reds”. The life-size reconstructions of wartime scenes in the War Memorial do include one graphic image of a grim-faced uniformed man pointing a gun at a woman, labeled “North Korean Secret Police Searching for the Patriotic People in the South”, but beyond this there are few specific details of acts of violence against civilians by Northern forces.

Diorama entitled “North Korean Secret Police Searching for the Patriotic People of the South”, War Memorial of Korea, Seoul

This, of course, has the convenient corollary of allowing the Memorial to remain equally silent on the subject of massacres or maltreatment of prisoners by Southern forces and their United Nations allies. For example, the Memorial’s explanation of the lead-up to the Korean War, as presented in multilingual video clips, tells visitors that in 1948 North Korea “tried to impede South Korea’s separate election, and especially on Jeju Island, communist sympathizers attacked and set fire to government offices and even killed people.” No mention here of the fact that the demonstrations on Jeju were largely a response to an earlier killing of civilians by ROK security forces, nor of the fact that the brutally-suppressed 1948-49 anti-government uprising on Jeju Island commonly known as the “Jeju 4.3 Incident” is now believed to have claimed the lives of almost 30,000 people, most of them islanders killed by South Korean troops and military auxiliaries. [16]

The contentious nature of the Memorial’s representation (or rather, lack of representation) of the killing of civilians both before and during the Korean War is a reminder of the fact that the Memorial itself is part of a deeply divided and contested South Korean public discourse on national history. Far from offering a universally-accepted, authoritative narrative of the Korean War, the War Memorial of Korea presents just one interpretation of the conflict – one with which many South Koreans would disagree. A radically different perspective on the war has, for example, emerged from the work of the Korean Truth and Reconciliation Commission established under the Roh Moo-Hyun government, which reached the conclusion that around 100,000 South Koreans were killed by their country’s own security forces in 1950 alone. [17] Predictably, too, the Memorial remains silent about topics such as the Nogun-Ri massacre of civilians by US forces, and about similar dark events whose traces may be found in war archives, in recent academic and public debate and (in fictional form) in the nightmares of Gran Torino’s main character Walt Kowalski. [18]

When I visited the Memorial in 2009, the pendulum of politics had swung to the other side of the divide: the Lee Myung-bak administration had renounced the Sunshine Policy, and tensions on the Korean Peninsula had reached a new peak. Against this background, my impression of the War Memorial of Korea was not so much of a place struggling to balance a triumphal military narrative with a message of reconciliation, but rather of a place beset by multiple paradoxes. One of these was the uneasy relationship between the Memorial’s defiant Korean nationalism and its propinquity to US Army Garrison Yongsan.

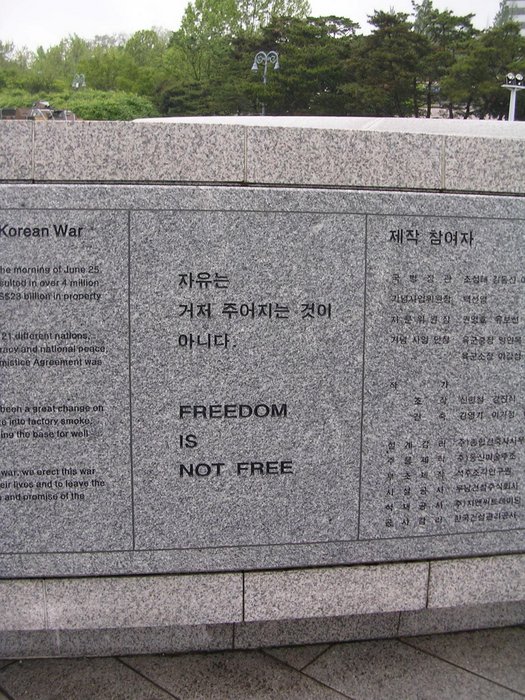

How, I wondered, did the nationalist symbolism of the Korean dagger fit with symbolism of the giant US B-52 bomber, whose outspread wings greet visitors even before they enter the Memorial’s doors? How does the emphasis on unending Korean resistance to cruel subjugation by foreigners relate to South Korean participation in the Vietnam and Gulf Wars and Afghanistan: events which are celebrated in the memorial as Korea’s contribution to the maintenance of global freedom? (Of the Vietnam War, the Memorial’s brochure tells us that the brave actions of South Korean troops “heightened the nation’s international position and greatly contributed to the nation’s economic development by giving Korean corporations a springboard for launching overseas operations.”) [19] What should one make of the ambiguous motto engraved in stone outside the Memorial Hall: “Freedom is not Free” [which in Korean translates into the much more cumbersome epigram: Jayu neun keojeo jueoji neun kos i anida]?

“Monument in Remembrance of the Korean War”, in the grounds of the War Memorial of Korea, Seoul

In the narrative of the war which the Memorial presents to its visitors, South Korea is a small, fragile democracy attacked by the juggernaut of international Communism, and saved by the bravery of the South Korean military and people with the support of the their US ally. The information accompanying the displays – both in written form and in ubiquitous multilingual videos, with sound-tracks in Korean, Japanese, English and Chinese – goes out of its way to emphasise that at the time of the war (unlike today) North Korea was the more industrialized and better-equipped half of the peninsula:

The ROK Armed Forces were caught off guard by the North Korean People’s Army (NPKA) invasion. While the NPKA were armed with tanks and fighters the South Korean had none. They also had less than half the North’s effective ground forces. They had no choice but to fight against the NPKA’s tanks with suicide attacks and to drop bombs by hand from training aircraft. Even with such suicidal tactics, there was no contending against such heavy odds, and the city of Seoul fell into the hands of the enemy in three days. [20]

Of the four museums described here, the War Memorial of Korea is the one that most vividly depicts the sufferings of Korean civilians during the war. On the other hand, it is less forthcoming on some aspects of the war which are highlighted by other museums. Chinese participation in the Korean War is emphasised, but the Memorial’s account implies that military conflict stopped at the border between North Korea and China – a story (as we shall see) very different from the one told by Dandong’s war memorial. The Seoul Memorial acknowledges the presence of the sixteen other countries who participated in the war alongside the United States under the United Nations Command, but it does so in a way which (intentionally or otherwise) seems to marginalize them from the main story. While the US is omnipresent in the Memorial’s narrative of the war, the other sixteen nations are largely confined to a separate room, which offers a very static display of uniforms, flags, and statistics. This is in strong contrast to the vivid and dynamic reconstructions of the heroism of South Korean soldiers and sufferings of civilians.

Through skilful use of video, photographs, and life-sized dioramas of ruined cities and columns of fleeing refugees, the Memorial seeks to convey the horror of conflict to a generation who can remember nothing but prosperity and peace (albeit an uneasy peace). Its Combat Experience Room mobilizes special effects to offer visitors “a vivid vicarious experience of the front line”. [21] But here too it seems to confront a dilemma. As I went round the Memorial examining its Korean War display, I was aware of the constant clamour of children’s voices in the background. Yet relatively few children were actually in the Korean War rooms, and those who were often seemed bemused by the scenes that confronted them. It was only as I left the Memorial that I understood where the children’s voices were coming from: in an effort to draw in young visitors, the Memorial had converted most of its lower ground floor into a giant play space which was currently featuring a Thomas the Tank Engine theme. This area was crowded with families. But although some of them probably also ventured out into the Memorial’s other halls, I am fairly sure that most of the young visitors went home with much clearer images in their heads of the Fat Controller and Salty the Dockside Diesel than they did of the Incheon Landing or the Panmunjeom armistice negotiations.

Following the dramas of suffering and heroism depicted in the Memorial’s narrative of war, indeed, the end of the Korean War comes almost as anti-climax: “After more than two years of talks between the UN and Communist sides, from July 10, 1951, until July 27, 1953, a ceasefire went into effect that has been maintained ever since… The ROK government was not a signatory of the Armistice Agreement.” [22] The Memorial is the only museum I have seen which acknowledges the fact that the armistice was opposed by the South Korean government and provoked demonstrations in the streets of Seoul. But beyond that, the rest is silence, and the story ends on a note neither of triumph nor of reconciliation, but rather of a kind of uneasy sadness.

The Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, Pyongyang

The museums of Pyongyang are resolutely modernist: great neo-classical edifices which tell an immutable and monolithic narrative; or so it seems on the surface. Certainly, in the DPRK there is no scope for public controversy about the nature and events of the Korean War. But the official narrative can be told in subtly varying ways; and visiting the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, I realised that it is in fact constructed in a form that allows for just such variety.

This effect is achieved by size. The museum contains a very large number of rooms: eighty in all, according to the guide who showed us round, although the plan attached to the official English guide-book shows thirty-four exhibition spaces. This is not a museum where you can wander at will – all visits are guided tours given by a uniformed member of the armed forces, and because of the size of the building they inevitably include only a limited sample of rooms; so the itinerary chosen affects the story told to the visitor. On my visits (I have been to the museum twice), the itinerary focused on the background to and outbreak of the war, the spoils of captured weaponry which illustrate the military feats of the Korean People’s Army, the evidence of ongoing US military aggression on the Korean Peninsula, and some of the battle panoramas which are among the museum’s highlights. Relatively little was said about other crucial issues. For example, the collaboration between North Korean, Chinese and Soviet forces was only briefly mentioned. But the published guidebook reveals that the museum also contains a “Hall Showing International Support” and a “Hall Showing the Feats of the Chinese People’s Volunteers”, and I am sure that these feature centrally in the tours given to Russian and Chinese visitors.

As the museum’s very name suggests, the story of the Korean War told here is radically at odds with the story told in Seoul’s War Memorial of Korea, and the differences between the two narratives offer important insights into sources of contemporary tensions on the Korean Peninsula. In the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, the story of the origins of the Korean War goes back to the years before 1945, and to the struggle of Korean nationalists – particularly of partisans led by Kim Il-Sung – against Japanese colonialism. On 15 August 1945, their struggle was rewarded when Korea gained its freedom from Japan, but the “US troops illegally occupied south Korea on September 8 Juche 34 (1945), forcibly dissolved the people’s committees set up in accordance with the will of the people, and arrested, imprisoned and murdered a large number of patriots.” [23]

Display representing the impact of the US military presence on life in late 1940s South Korea, Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, Pyongyang

Like other North Korean historical exhibitions, the Victorious Fatherland War Liberation Museum presents its story in a format that relies heavily on the marshalling of archival evidence to support particular truth claims. Unlike the War Memorial of Korea, the Pyongyang museum makes (as far as I can tell) absolutely no use of documentary video, but abundant use of still photographs and facsimiles of documents, including South Korean and foreign newspaper reports and letters from the US archives. These are deployed, for example, to present a rather detailed and convincing image of the impact of the US military on South Korean society and of the arrests and killings of opponents of the Yi Seungman regime. Less convincing are the museum’s efforts to document one of the central North Korean contentions: that the DPRK was the victim of an unprovoked attack by US and South Korean forces. The key pieces of evidence offered here are newspaper reports showing that Yi Seungman was ready and eager to launch an attack against the North (which is indisputably true), and a letter from John Foster Dulles (then America’s UN representative) to South Korean Foreign Minister Lim, referring to the need for “courageous and bold decisions” – which could mean almost anything.

In the Pyongyang museum’s version of events, it is not the South but the North that is weak and vulnerable. The newly created Korean People’s Army is taken by surprise by the attack from the south, but, under the guidance of the Great Leader Kim Il-Sung, launches a counter attack that aims to liberate the entire Peninsula within the forty days which it will take the US to bring reinforcements in from its bases around the world. This strategy is almost but not quite successful, and after a massive influx of US troops, Kim Il-Sung orders the People’s Army to make a strategic retreat to the north. However, US planes launch bombing raids across the border into China, prompting the Chinese People’s Volunteers join the fight against imperialism, the re-invigorated Korean People’s Army drives southward, and the war ends in victory over the aggressors.

Kim Il-Sung leads his people to victory: Painting displayed in the entrance to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang

The contrast between the Pyongyang and Seoul museums, however, lies not only in their narrative of events, but also in the overall image of war which they convey. There can be no doubt that the people of North Korea suffered horribly during the war. To give just one example, as Steven Hugh Lee notes in his history of the Korean War, in a single raid on the North Korean capital on 11 July 1952, “US, ROK, Australian and British bomber pilots flew 1,254 sorties against Pyongyang, dropping bombs and 23,000 gallons of napalm on the inhabitants. After two more major bombing campaigns against the city in August the Americans decided that there were too few targets left to justify a continuation of the bombardment.” [24] The portrayal of such sufferings in the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, however, is very muted, and this absence of reconstructions of pain and death (such as those presented by the War Memorial of Korea’s wax works of starving and desperate refugees) appears to be part of a conscious strategy of presenting the war as victory: a site of strength, heroism and triumph. Depicting North Koreans as victims, particularly before the gaze of foreigners, might be taken as a sign of weakness.

Experiences of bombing, death, injury and displacement are depicted in other North Korea media, including magazines, novels and film. The sections of the museum which I saw, however, contained only brief references to these events, and a few grainy photographs of bombed cityscapes. There is one small room dedicated “the US Imperialist Aggressor’s Atrocities”, which (to judge by the museum’s guidebook) contains more graphic photographs of civilian suffering, but this was not on our itinerary. Rather than incorporating such stories into the Pyongyang Museum, the North Korean authorities have separated them out into a distinct site of memorial – the Sinchon Museum, south of Pyongyang, which commemorates a massacre in which North Korea claims that US troops killed more than 35,000 people. In the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, it is US enemy troops, rather than Korean soldiers or civilians, who are shown as wounded, captured and suffering. In this, the museum follows a tradition which was common in the Soviet Union and is also evident in some Chinese war memorials today: the narrative is one of triumphant heroism against overwhelming odds, a story to inspire the soldiers of the future, rather than to remind the populace of the misery of war.

The theme of victory is re-emphasised by the museum’s extensive exhibits of captured US weaponry, and by its dioramas: for the Pyongyang museum uses the technique of the diorama even more dramatically than its Seoul counterpart. Its major dioramas (our guide told us) are by far the most popular sections of the museum, particularly with schoolchildren, and they are indeed remarkable samples of the genre. One depicts the struggle of the People’s Army and local villagers to keep open the strategic Chol Pass under a barrage of US bombing raids. This is accompanied by a recorded commentary and atmospheric music, with lighting and a variety of “special effects” creating the spectacle of lines of trucks snaking over the pass as enemy bombers swoop overhead. The second, a huge cyclorama which shows the North Korean capture of the town of Daejeon, south of Seoul, is said to contain a million painted or sculpted human figures, and is viewed from a rotating platform, giving the spectator the sense of looking down on the scene from a hilltop in the midst of the battlefield.

Section of the diorama illustrating the Battle of Daejeon, Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, Pyongyang.

Within this drama of heroism and victory, it should be noted, there is almost no reference to the involvement of any countries other than the United States in the UN Command. The emphasis throughout is on US imperialism and aggression, and the war, in short, is narrated as a resounding victory of the DPRK over the United States. To quote the words of another North Korean book on the subject:

By winning victory in the war, the Korean people shattered the myth of the ‘might’ of US imperialism, the chieftain of world imperialism, and marked the beginning of a downhill turn for it, thus opening up the new era of the anti-imperialist, anti-US struggle. [25]

This view of the war is diametrically opposed to the one presented in Seoul’s War Memorial of Korea; but it does allow the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum to achieve an effect also pursued by its South Korean counterpart. The image of American imperialism as the enemy, in other words, leaves open the possibility of reconciliation with the South, whose people rarely appear in the museum’s displays, either as victims or as aggressors.

But the constantly repeated theme of victory over US aggression, in the end, strikes an edgy and insecure note. When wars are irrefutably victories, after all, it generally ceases to be necessary to label them “victorious”. In the case of the Korean War, the North Korean need to pronounce the war a victory seems to have become ever greater, the longer the division of the Peninsula has continued and the more the South has prospered. The museum in Pyongyang was originally opened in 1953 as the “Fatherland Liberation War Museum”; it was only when a new and grander museum was unveiled in 1974 that the word “Victorious” was added to its title. In a sense, indeed, I cannot help being reminded of the yet-to-be completed Korean War National Museum in Springfield, Illinois, whose V-sign logo celebrating “the forgotten victory” seems like a similar attempt to silence a nagging uncertainty. The desire of so many national monuments to trumpet the term “victory” could, paradoxically, be read as a clear sign that this was a war that no-one won.

The Pyongyang museum’s proclamation of victory is in fact at odds with the message of its displays, which seems to be that the war has never ended at all. The exhibit of war trophies is ever-expanding, added to with the capture of the US intelligence-gathering vessel Pueblo in 1968 and with wreckage and weapons from a series of minor clashes on the 38th parallel, continuing into the 21st century. The theme of unending US aggression and deceit is a much-repeated one, also emphasised in the exhibitions elsewhere in Pyongyang and on the northern side of the dividing line at the truce village of Panmunjeom. There, as in the Pyongyang war museum visitors are reminded of the massive alien military presence on the doorstep of the DPRK: a country which has had no foreign troops on its soil for more than half a century. The abiding impression, far from being one of a confident victor flaunting its military triumphs, is of an embattled society where constant repetition of the word “victory” is a mantra for warding off the unspeakable but always present threat of annihilation.

The DPRK claims to have captured this US miniature unmanned submersible vessel (now on display in central Pyongyang) close to its eastern coast in 2004

The Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong

To understand the present crisis on the Korean Peninsula it is essential to understand the position of China; and China’s position cannot be comprehended without knowledge of the way in which Chinese people experienced and remember the Korean War. The Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea in the border city of Dandong is a vivid embodiment of the deep and complex feelings which the Chinese government and people – or at least the people of the northeastern provinces of China – hold towards North Korea. From a Chinese perspective, the war was a heroic act of solidarity with a smaller and embattled neighbour, but also a war that they did not want, and the appropriate response to the crisis on the Korean Peninsula in 1950 presented China’s leaders with profound dilemmas. The symbolism of the memorial is therefore replete with reminders of the Chinese-Korean joint struggle against US imperialism, but also of the potential threat to China which lurks on the Korean side of their common border. The DPRK, in short, is presented as a small and vulnerable buffer between China and US military might in Asia, and is thus to be protected; but also as a country whose problems have real and menacing implications for China itself.

The memorial’s history goes back to 1958, the year when the last of the Chinese “volunteer” forces withdrew from North Korea. Initially China’s part in the Korean War was commemorated in a more modest adjunct to the Dandong historical museum, but in 1993, at the time of the fortieth anniversary of the Korean War Armistice, it was reopened in an impressive granite and marble hall on a hilltop behind the city. [26] To reach the memorial, you climb a long flight of steps surmounted by dramatic socialist-realist sculptures of Chinese soldiers, their guns trained towards the menace that approaches from the North Korean side of the Yalu river – just visible on the horizon from the memorial’s forecourt. Between the statues stands a tall stone obelisk – built in a style which is also widely used for monuments in North Korea – commemorating the armistice which (from the official Chinese viewpoint) marked the victory of the DPRK and its allies.

Looking out towards North Korea – statues outside the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong

The background to the war, as seen from Dandong, is very different from the background depicted in Pyongyang’s Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum or in Seoul’s War Memorial of Korea. Here, the story starts with the liberation struggles of the Communist Party of China (CPC), whose victory celebrations are disrupted and menaced by the events unfolding in Korea:

In October 1949, the Chinese people, under the leadership of the CPC, achieved the great victory of the new democratic revolution and founded the People’s Republic of China. The new-born China was faced with grave war scar and difficulties in economy. A thousand and one things waited to be done… Just when the Chinese people began to restore economy and develop production for the consolidation of the new state power, the Korean War broke out and the US immediately made incursions into the DPRK and moreover drew the flames of war towards the Yalu River. At the same time, the US sent its army and navy to the Chinese territory, Taiwan. [27]

From the Chinese point of view, the timing could hardly have been worse. The country was exhausted from decades of civil war. As some historians have pointed out, there also appeared to be signs in 1950 that the US might have been willing to relinquish Taiwan and move towards recognition of the PRC, but all this was changed by the outbreak of the Korean War and by the use of Taiwan as a staging post for US troops heading for Korea. [28]

The Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea develops its account of the conflict through a series of large exhibition halls, making abundant use of historical artifacts as well as photographs, written documents and sculpture. It also contains one great cyclorama, very reminiscent of the Pyongyang panorama of the Battle of Daejon, but here representing the Battle of the River Cheongcheon [Qingchuan in Chinese], a major engagements between Chinese troops and US forces. Uniforms, knapsacks and other items of everyday war life are used to dramatize the hardships faced by the Chinese volunteers, who first crossed the Yalu River to drive back the advancing South Korean and United Nations forces on 19 October 1950. Interestingly, the Dandong memorial (unlike its counterpart in Pyongyang) repeatedly acknowledges the presence of a multinational United Nations force, but presents this as having been essentially a front for US policy: the term “United Nations Command (UNC)” is always written in scare quotes. The memorial’s narrative also argues that internal disagreements among the states participating in the UNC was a major factor impelling the US to seek a negotiated armistice. [28]

Statue of Mao Anying, Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong

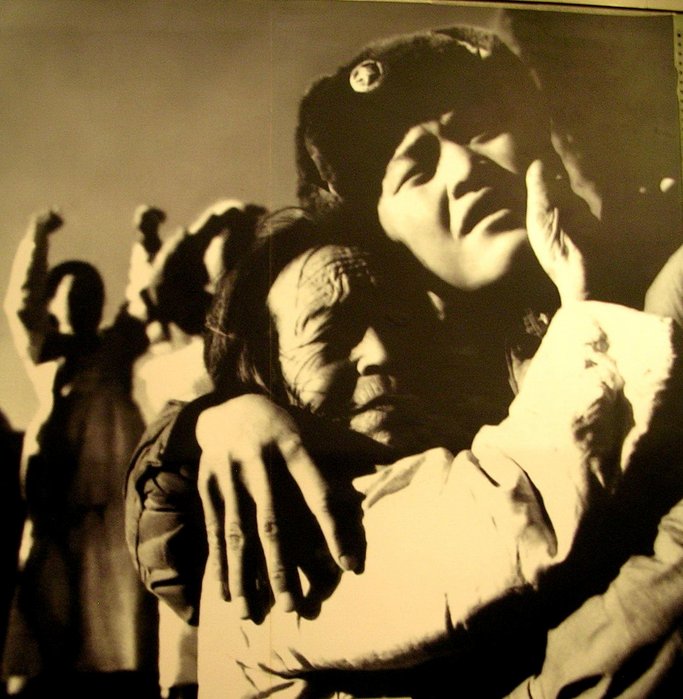

The faces of the heroic Chinese volunteers line one entire exhibition room – a reminder of the fact that around one million Chinese people are thought to have been killed or injured during the war. [30] A simple white bust commemorates perhaps the most famous of them: Mao Anying, the eldest son of Chinese leader Mao Zedong, who was killed in battle in Korea in November 1950. Predictably, the relationship between Chinese volunteers and North Koreans is represented as an exemplary one – Chinese forces come to the aid of their Korean comrades-in-arms and help and feed injured Korean civilians. If the South Korean idealized image of reconciliation is embodied in the War Memorial of Korea’s “Statue of Brothers”, the Dandong memorial’s idealized image of the relationship between Chinese and North Koreans is represented by a giant photograph of an elderly Korean woman embracing a young uniformed Chinese volunteer. Here too, the implicit inequalities are striking: the tall, virile Chinese soldier towering over the frail, wizened Korean woman. At the same time, though, there is something genuinely powerful about this photograph. I try and fail to imagine a similar image of the relationship between US forces and South Korean civilians. It is reminder of the fact that the China which went to the help of the DPRK in 1950 was not a nuclear superpower but was itself a poor agrarian country. The social gap between Chinese volunteers and North Korean civilians was much smaller than that between US forces and local civilians in the south.

Korean civilian and Chinese volunteer – Photograph displayed in the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong

The Chinese memorial in fact gives a fuller and more vivid impression of the suffering of North Korean civilians than does the DPRK’s own war museum. Its photographs offer graphic depictions of devastation produced by the bombing of North Korean towns and villages, and of lines of refugees fleeing the fighting – many of them heading across the Yalu River into China. There are also exhibits dedicated to the claim that US forces used biological warfare in Korea – a claim echoed in the war museum in Pyongyang. [31] The dangers of war in Korea spilling over into China are dramatized by photos, not only of the influx of refugees across the river, but also by images of the bombing of the rail-bridge spanning the Yalu River between Dandong and the North Korean city of Sinuiju. One half of the destroyed bridge still stands, and is among Dandong’s main tourist attractions. The war memorial’s displays of photos of damaged buildings and injured civilians in Dandong and surrounding towns are a sharp reminder of the bombing raids across the border into Chinese territory which were carried out by US planes on several occasions during the war.

One distinctive feature of the Chinese memorial is the fact that, as well as emphasising the impact of the war on China and the relationship between the Korean conflict and the Taiwan issue, it casts a somewhat unfamiliar light on the contentious question of the maltreatment of prisoners-of-war. In the United States and its allies (including Australia) perhaps the best-remembered aspect of the war was the killing, maltreatment and “brainwashing” of prisoners-of-war by North Korea. It was during the Korean War that the term “brainwashing” came into general use in English. In the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, on contrary, the displays on maltreatment of prisoners of war all relate to the sufferings of Chinese and North Korean prisoners in South Korean prisoner-of-war camps.

An important obstacle to the signing of the armistice was the question of whether all prisoners-of-war should be returned to their countries of origin after the conflict, or whether some would be allowed to defect. For example, would North Korean soldiers who wished to change their allegiance to South Korea be allowed to do so? Would Chinese soldiers who renounced communism be allowed to go to Taiwan rather than being sent back to the PRC? The United States and its allies favoured allowing prisoners-of-war in Southern prisons to determine their own destiny, while the DPRK and China insisted that all should be returned to their place of origin.

However, as documented in the records of the International Committee of the Red Cross (which inspected Southern but not Northern prisoner-of-war camps) the US stance had troubling consequences. In the overcrowded ROK prisoner-of-war camps, violent contests for the allegiance of inmates broke out, both between prisoners themselves and between prisoners and their guards, resulting in assaults, lynchings and even the forcible tattooing of political slogans on the skin of some inmates (events dramatically reconstructed in Ha Jin’s novel War Trash). Particularly widespread violence occurred at the massive Koje-Do prisoner-of war camp, but there were also serious incidents elsewhere, including one at a camp on Jeju Island where, on 1 October 1952, guards from the UN Command fired on rioting Chinese prisoners-of-war killing over fifty people. [32] It is this issue (and not, of course, the mistreatment of prisoners-of-war in the DPRK) that is commemorated in Dandong, where it is used to emphasise both the courage of the Chinese volunteers and the violence inflicted on both North Koreans and Chinese by the US (whose control over the camps is stressed in the memorial’s narrative).

The story told in the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea ends, not with the armistice of 1953, but rather in 1958, when the Chinese volunteers who had stayed on in North Korea to work on postwar reconstruction projects finally returned home. Despite the memorial’s frequent references to a friendship between PRC and DPRK forged in blood, there is evidence that the continuing presence of Chinese troops on Korean soil after the armistice led to increasing tensions with the local population. [33] Meanwhile, Mao’s China was embarking on its ill-fated “Great Leap Forward”, and had its own pressing concerns. Against this historical background, and amid unsuccessful calls for the removal of all foreign troops from the Korean Peninsula, North Korea was left to defend itself.

Like the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum in Pyongyang, the Dandong monument presents an official, state controlled history whose broad outlines are rarely challenged in public discourse. Its rhetoric of victory over brutal American imperialism also echoes North Korean rhetoric. But looking at the interaction between visitors and exhibits in Dandong, I could not help feeling that something else was also going on here. I visited the memorial with two British companions on a holiday weekend, when the building and its forecourt were full of students and young families, many of them stylishly dressed in fashions that could have come from Paris or LA. Several of the children clutched Hello Kitty balloons in one hand as they surveyed the images of devastated Korean cities and of the Chinese victory on the Cheongcheon. Many of the college students were eager to be photographed with us, and seemed much more interested in practicing their English than in perusing evidence of US imperialism on the Korean Peninsula – an imperialism of which we, presumably, should have been seen as representatives. Just one old man (perhaps a veteran of the war) looked on with an expression of quiet disapproval.

Visitors viewing the cyclorama of the Battle of the River Cheongcheon, Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong

From the perspective of China, North Korea is no longer a fellow struggling revolutionary state. It is a society whose political economy and lifestyle stand in stark contrast to China’s new-found prosperity, but whose political crises have the potential to interrupt the enjoyment of that prosperity. While China has opened itself to the outside world and developed close economic ties with former enemies such as the US and Japan, North Korea for complex internal and external reasons, remains frozen in the Cold War era. The changed Chinese perspective on its Korean neighbour does not, of course, mean that China’s narratives of the Korean War are about to be rewritten along US or South Korean lines. Rather, this shift highlights the uncomfortable position of North Korea as the interstice between the long-standing US presence in Asia and the newly-emerged Chinese global power. In both the US and China, long-standing memories (or forgettings) of the Korean War face new challenges. How the memory of the war is rewritten in both countries will affect, and be affected by, the changing balance of power in Asia.

The Australian War Memorial, Canberra

The Australian War Memorial occupies a powerful symbolic location in the geomancy of the planned capital of Canberra. Located at the end of one of the major avenues that radiate out from the core of the city – Parliament House – its site embodies the insoluble bond between war and the nation. Within the memorial, though, the space dedicated to the Korean War is relatively small – one-and-half rooms on the lower floor. To reach it, you must pass a long line of photographs recalling Australians’ involvement in a whole range of conflicts, from the Boer War to Iraq. Pride of place belongs to the First and Second World Wars. For Australia, as for China, the Korean War was an unwelcome event which arrived just as the nation was recovering from a much larger conflict. Australians, as the memorial’s display reminds visitors, were among the first to respond to the United Nations’ call for forces to serve in Korea, but the scale of Australia’s involvement (compared to that of China or even the United States) was relatively small in terms of total numbers – around 17,000 Australians served in the Korean War, and 339 were killed. [34]

View of Parliament House from the forecourt of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra

Like the War Memorial of Korea, the Australian War Memorial aims to convey the story of war to young generations who know nothing but peace (or, more precisely, who live in a country where recent engagements in war have been far away events in foreign countries); and it uses similar techniques to draw in a youthful audience. In this case the theme (when I visited) was not Thomas the Tank Engine but “A is for Animal”, a special children’s display of mammals, birds and even insects at war, featuring everything from camel-riding soldiers to carrier pigeons. The effect, however, seemed similar to that achieved in Seoul. There were plenty of children in the building, but few wandered into the rooms devoted to the Korean War, and those who did seemed to wander out again rather quickly.

The design of the Australian War Memorial’s Korean War section, which was remodeled in 2008, is surprisingly reminiscent of the much larger Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea in Dandong. Like its Chinese counterpart, the Australian memorial makes much use of artifacts – uniforms, backpacks, water flasks, packets of cigarettes etc. – to evoke the life of soldiers at the front. Since several of the main Australian engagements were with Chinese forces, the Canberra memorial includes a substantial display of objects captured from Chinese soldiers, including a rather touching array of photographs and other personal items from a Chinese woman soldier killed in battle. Like all the museums I have discussed here, the Australian War Memorial also seeks to convey the experience of battle through the use of dioramas. Here it is the April 1951 Battle of Kapyong, in which Australians played a central part, that is immortalized in diorama form. This reconstruction brings the story of the battle to life with the help of a soundtrack of the voice of a veteran describing his experiences, but the size and visual effect of the diorama itself is far less impressive than that of the Pyongyang museum’s reconstruction of the struggle for the Chol Pass.

After a rather cursory explanation of Korean history, the Australian War Memorial tells visitors that on 25 June 1950 Soviet-backed North Korea invaded South Korea. The UN Security Council demanded the North Koreans withdraw. When they refused, the United Nations intervened, led by the United States. Twenty countries, including Australia, eventually responded to the UN appeal. No one realised the war would last for three years and that occupation forces would be required for some years after. [35]

In the Australian War Memorial, then, the United Nations Command is centre stage, with the focus (unsurprisingly) being on its Australian contingent.

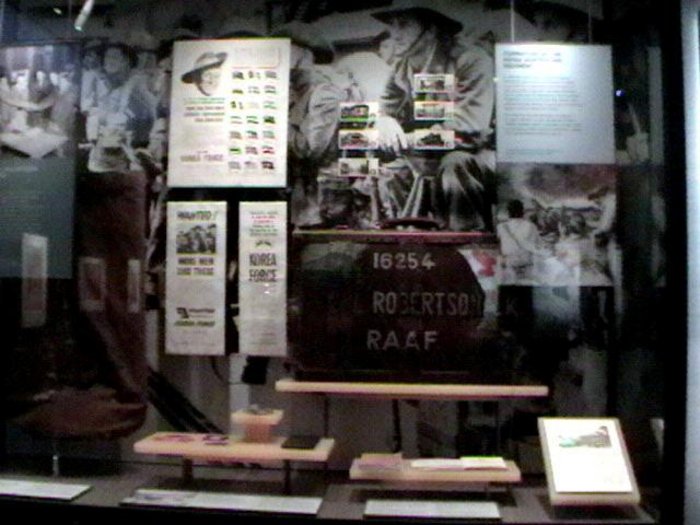

Display illustrating Australian participation in the Korean War, Australian War Memorial, Canberra

The unprovoked nature of the North Korean attack is strongly emphasised in the Australian War Memorial, which cites a visit by two Australian officers to the 38th parallel shortly before the war broke out. On the basis of their observations, the officers concluded (according to the memorial’s account) that “South Korean forces were organized entirely for defence”. [36] Missing from this account are the repeated reports (some of them from Australian observers) of the belligerence from the Southern side which provided an important part of the background to war. For example, in 1949 the South Korean Prime Minister, proposing a toast to officials of the United Nations Commission on Korea (UNCOK), proclaimed that “his next drink would be in Pyongyang”. The Commission’s Australian head took this boast seriously: “Foreign Missions in Seoul agree that there is a possibility that the Government may feel sufficiently strong to embark on an attack of the North within a few months”. [37]

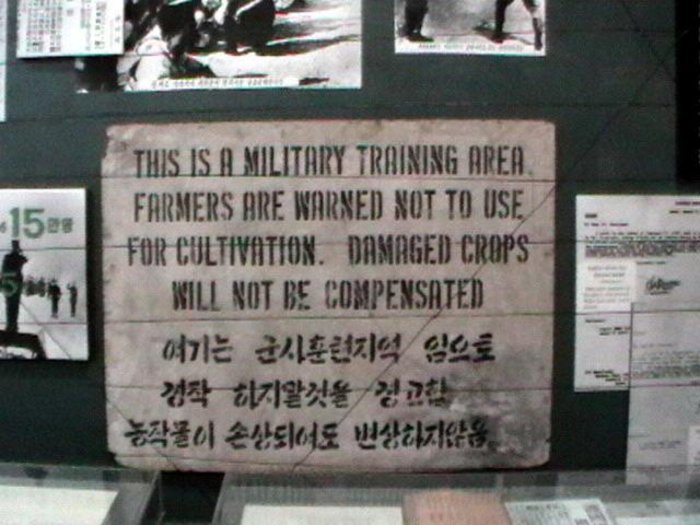

Looking at the war from an Australian perspective, however, also has other unexpected effects. For example, it reveals an intriguing aspect almost entirely absent from the other three war museums discussed here – the Japanese dimension of the Korean War. Because Japan was not a combatant, and was under allied occupation when the war began, it is easy to forget how significant a place Korea’s former colonial ruler played in the conflict. But, as the Canberra memorial displays reveal, Australians were able to respond quickly to the UN call because they were already based in Japan. “Thousands of Australians,” the memorial notes, “visited Japan on their way to Korea or on leave from the war”. [38] Australian nurses who looked after the wounded were mostly based at hospitals in Japan. Indeed the headquarters of the United Nations Command itself was located in Tokyo, while the factories of Japan provided massive logistical support for the UN forces fighting in Korea. Exhibited items from the everyday life of Australian servicemen fighting in Korea include booklets on life in Japan and a language primer entitled Japanese in Three Weeks.

Among the exhibits are also letters home sent home to Australia by soldiers in Japan, waiting to go into combat in Korea, and these remind us of other neglected aspects of the impact that this mass of foreign troops had upon the society of Northeast Asia: an Australian serviceman (with rather endearing frankness) writes home to ask Mum for a large parcel of goods, including a large amount of saccharine which, he explains, is “intended for sale on the local black market, but if anyone asks it will do me no harm if you say that I have diabetes.” [39] Other social aspects of the war, such as its impact on the spread of prostitution, and the whole dark topic of rape in war, are mentioned in none of the museums I have visited, though the issue of rape is hauntingly evoked in some Korean fiction on the war period – works like Pak Wanseo’s Three Days in That Autumn [Keu kaeul eui saheul tongan]. [40]

Faces of Australian servicemen, as well as paintings and photographs by Australian participants in the war, line the walls of the Australian War Memorial’s Korean War display. There is, however, one noticeable difference between these images and the faces of the Chinese volunteers in Dandong, or of South Korean servicemen on the walls of the War Memorial of Korea. In China and Korea the servicemen remembered are heroes – people singled out for exceptional deeds of valour during the war. The Australian War Memorial, on the other hand, prides itself on remembering the “ordinary digger” – soldiers who may have done nothing more remarkable than to survive long enough to tell their tale.

On the other hand, this memorial conveys little impression of the wartime fate of ordinary Korean civilians. A two-sentence statement reminds visitors that “the war had a devastating impact on Korea. Over two million civilians were killed”. But there are almost no images of destruction to Korean life and property, and the documentary footage of bombing raids shown on the video screens present the bombing always from the birds-eye view of the pilot, not from ground level. The most detailed description of human suffering concerns the plight of Australian prisoners-of-war, some of whom endured interrogation, isolation, extreme deprivation and torture at the hands of their captors. The War Memorial’s display on prisoners-of-war discusses the issue of “brainwashing”, and rightly notes that “imprisonment under the North Koreans and Chinese was extremely harsh. Little respect was paid to the 1949 Geneva Convention”. On the other hand, the memorial’s narrative of the war remains silent on the violence in Southern prisoner-of-war camps, and justifies the UN Command’s stance on the prisoner-of-war issue by stating (incorrectly) that the “Geneva Convention forbade the forcible repatriation of prisoners of war”. [41]

Unlike the museums in Springfield Ill., Pyongyang and Dandong, the Australian War Memorial seems to have no impulse to proclaim the Korean War as a “victory”. Australians have a long history of fighting in other people’s war, with very mixed results, and this may help to explain a willingness to depict the war’s outcome as a stalemate. The section devoted to the Korean War flows almost seamlessly into other Cold War conflicts in which Australians took part: the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesian Confrontation, the Vietnam War. One war ended, but the Cold War went on. The memorial’s bald account of the signing of the armistice concludes with the words: “a peace treaty has never been signed and Korea lives on a war footing, no closer to unification than in 1950”. [42] By the time visitors read this, they are already being half-deafened by the roar of the genuine working helicopter which is the highlight of the section dedicated to the Vietnam War, just round the corner.

Beyond Structured Absence

The monuments we have explored here call themselves by various names. Some describe themselves as “memorials”, others as “museums”. But in fact, all seek to combine the tasks of commemoration and of communicating history – and therein lies a dilemma. A memorial may have multiple purposes. At one level, memorials (like graves) are deeply personal. They are places where the relatives and comrades of the dead come to remember and mourn those they loved. In this sense, there is no need for a memorial to be impartial or judicious, or to tell the whole story of a conflict. All it needs to do is to provide comfort and a focus of memory for those who have suffered loss. At another level, however, many memorials (and certainly all the ones I have discussed here) have a public and national role. They are intended, not simply to speak to those with personal connections to the war, but also to convey a message to the nation. In this respect all the monuments I have discussed speak with one voice (though to different audiences): their message is always: “our military fought a heroic fight against unprovoked aggression”. Some would also add the pronouncement “… and won.” Superimposed upon this ambivalent role as personal and as public memorials, all four monuments also proclaim their credentials as museums. They aim, not simply to provide a material focus for commemoration, but also to convey the story of the war to a generation who did not experience it.

How can these three roles possibly be reconciled? How can a memorial simultaneously preserve the memories of the individual dead (whose deaths may have been dramatic and heroic or messy and inglorious), provide a positive focus for national pride and tell a comprehensive and balanced story of the war to future generations? The task is surely an impossible one, and this attempt to achieve the impossible is one reason for the depth of the divide between the versions of Korean War history presented in the museums I have discussed. This dilemma affects countries where political debate is relatively free, as well as those where it is tightly controlled. In Australia and South Korea there is far more public scope to debate and criticize the content of war memorials than there is in China or North Korea. But in Australia and South Korea, as well as in China and North Korea, the tensions between commemoration, national identity-making and history-telling produce structured absence.

Politics and history flow into one another. Divergent memories of the Korean War fuel the fears that produce contemporary political tensions; political tensions in turn make it harder to create the dialogue that might help to reconcile divergent memories. Roland Bleiker and Young-Jin Hoang, in their study “Remembering and Forgetting the Korean War”, stress the value of “tolerating different coexisting narrative” of the war. [43] But it is also equally important that different narratives be brought into contact with one another. The task for historians – particularly for historians who live in countries where official versions of history can be publicly debated – is to use all means made available by our globalised media to set national narratives side by side. In this way the war memorials of each country can (as it were) be virtually joined into a single space. So, perhaps, the wall surrounding each nation’s memorial may be broken down, or at least perforated, allowing the light of every national narrative (however faintly and distantly) to illuminate the darkness of the others, and enabling the perspectives of the many victims of war to emerge from the shadows.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History, Convenor of the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, and a Japan Focus associate. Her most recent book is Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki,”Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 29-4-09, July 27, 2009.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War. • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas. • Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Kim Dong-choon, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Wada Haruki, From • Nan Kim |

Notes

[1] One report which did raise this point appeared in The Australian on 27 May 2009.

[2] Sheila Miyoshi Jager, Narratives of Nation Building in Korea: A Genealogy of Patriotism, Armonk, M. E. Sharpe, 2003.

[3] Bruce Cumings, “The Korean War: What is it that We are Remembering to Forget”, in Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter eds, Ruptured Histories: War, Memory and the post Cold War in Asia, Harvard, Harvard University Press, 2007, pp. 266-290.

[4] Philip West and Suh Ji-Moon, Remembering the ‘Forgotten War’: The Korean War through Literature and Art, Armonk, M. E. Sharpe, 2001. On changing Korean memories of the war, see also Roland Bleiker and Young-Ju Hoang, “Remembering and Forgetting the Korean War: From Trauma to Recollection”, in Duncan Bell ed., Memory, Trauma and World Politics: Reflections on the Relationship between Past and Present, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, pp. 195-212.

[5] See for example, David R. McCann, “Our Forgotten War: The Korean War in Korean and American Popular Culture”, in Philip West, Steven I. Levine and Jackie Hiltz eds, America’s Wars in Asia: A Cultural Approach to History and Memory, Armonk, M. E. Sharpe, 1997, pp. 65-83; Paul M. Edwards, To Acknowledge a War: The Korean War in American Memory, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2000, particularly pp. 23-26; West and Suh eds., Remembering the “Forgotten War”; Roland Bleiker and Young-Ju Hoang, “Remembering and Forgetting the Korean War: From Trauma to Reconciliation”, in Duncan Bell ed., Memory, Trauma and World Politics: Reflections on the Relationship Between Past and Present, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, pp. 195-212; Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Jiyul Kim, “The Korean War after the Cold War: Commemorating the Armistice Agreement in South Korea” in Jager and Mitter eds, Ruptured Histories, op. cit., pp. 233-265; Bruce Cumings, “The Korean War” op. cit.

[6] Ha Jin, War Trash, New York, Pantheon Books, 2004.

[7] See Charles J. Stanley, Sang-Hun Choe and Martha Mendoza, The Bridge at No Gun Ri:A Hidden Nightmare from the Korea War, New York, Henry Holt and Co, 2001; Kill ‘em All: The American Military in Korea (producer, Jeremy Williams), BBC TV “Timewatch” series, first broadcast 1 February 2002.

[8] See the Korean War National Museum website, accessed 1 June 2009.

[9] Korean War National Museum website op. cit.; the photograph is uncannily reminiscent of the famous Life magazine photograph of an abandoned little boy taken among the ruins of Shanghai’s railway station after it was bombed by the Japanese in 1937.

[10] Sun Hongjiu and Zhang Zhongyong eds., Ninggu de Lishi Shunjian: Jinian Zhongguo Renmin Zhiyuanjun Kangmeiyuanchao Chuguo Zuozhan Wushi Zhounian, Shenyang: Liaoning Renmin Chubanshe, 2000 (English translation as in the original).

[11] See Susan A. Crane, “Introduction: Of Museums and Memory”, in Susan A. Crane ed., Museums and Memory, Stanford, Stanford University Press, pp. 1-16; 2000; Sheila Watson, “History Museums, Community Identities and a Sense of Place: Rewriting Histories”, in Simon J. Knell, Suzanne MacLeod and Sheila Watson eds., Museum Revolutions: How Museums Change and Are Changed, London, Routledge, 2007, pp. 160-172; Tessa Morris-Suzuki, The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History, London, Verso, 2005, ch. 1.

[12] Jager and Kim, “The Korean War after the Cold War”, p. 242.

[13] War Memorial of Korea, Seoul, n.d., p. 4. The emphasis on Silla as the origin of a united Korea is disputed by North Korean historians.

[14] Jager and Kim, p. 252; Jager and Kim are here citing the work of Pai Hyung-Il on Korean archaeology and national identity.

[15] Jager and Kim, pp. 246-252.

[16] See for example Mun Gyong-Su, Saishûtô 4.3 Jiken: ‘Tamuna”no Kuni no Shi to Saisei no Monogatari, Tokyo, Heibonsha, 2008, p. 8.

[17] Do Khiem and Kim Sung-Soo, “Crimes, Concealment and South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 1 August 2008.

[18] For recent discussions of the Nogun Ri and other massacres, see for example Charley Hanley, “The Massacre at No Gun Ri: Army Letter Reveals US Intent”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 15 April 2007; Bruce Cumings, “The South Korean Massacre at Taejon: New Evidence on US Responsibility and Cover Up”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, 23 July 2008.

[19] War Memorial of Korea, op. cit., p. 28.

[20] War Memorial of Korea, op.cit., p. 21.

[21] War Memorial of Korea, op. cit., p. 27.

[22] War Memorial of Korea, op.cit., p. 25.

[23] Hyon Yong Chol, Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, Pyongyang, Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, n.d., p. 6. Since 1997 the North Korean government officially has used the Juche calendar, under which years are numbered from 1912, the date of the late DPRK leader Kim Il-Sung’s birth.

[24] Steven Hugh Lee, The Korean War, Harlow, Pearson Education Ltd., 2001, p. 88.

[25] Kim In Il, Outstanding Leadership and Brilliant Victory, Pyongyang, Korea Pictorial, 1993, p. 63.

[26] On the history of the memorial, see Dandong Municipal People’s Government, “Memorial of War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea”, press release 19 June 2005, accessed 10 June 2009.

[27] Explanatory panel in the Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea, Dandong; viewed 2 May 2009.

[28] Gye-Dong Kim’s Foreign Intervention in Korea, Aldershot, Dartmouth Press, 1993, p. 123, is among the works that points out the US’s seeming hesitation about defending Taiwan in 1950.

[29] Gye-Dong Kim’s Foreign Intervention in Korea, Aldershot, Dartmouth Press, 1993, p. 123, is among the works that points out the US’s seeming hestation about defending Taiwan in 1950.

[30] Lee, The Korean War, p. 126.

[31] Controversy has surrounded these claims ever since they were first raised in 1952. In 1998 the Sankei, a right-of-centre Japanese newspaper, published excerpts from a set of documents which its Moscow correspondent claimed to have found in the state archives of the former Soviet Union. These documents ostensibly proved that public statements by the DPRK and its allies that the US had used biological weapons were deliberate lies fabricated for propaganda purposes. However, questions still surround the Japanese journalist’s research. The Sankei reporter is said to have copied the documents by hand (since photocopying was not permitted), and no other researcher has since managed to obtain access to the originals. Nor has the US government pressed the Russians to release these documents. For further details of the controversy surrounding this issue, see Kathryn Weathersby, “Deceiving the Deceivers: Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang and the Allegations of Bacteriological Weapons Use in Korea”, Cold War International Project Bulletin, no. 11, 1998; Peter Pringle, “Did the US Start Germ Warfare?” New Statesman, 25 October 1999.

[32] G. Hoffmann, “Rapport confidential concernant l’incident au Compound no. 7 de UN POW Branch Corps 3A, Cheju-Do du 1er octobre 1952”, in archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Geneva, file number B AG 210 056-012, Incidents dans les camps, 08.02.1952-13.04.1953.

[33] In December 1957, the Soviet Ambassador in Pyongyang, A. M. Ivanov recorded the content of a meeting with his Chinese counterpart in his official diary. During this meeting the Chinese Ambassador remarked that the withdrawal of Chinese volunteers from North Korea would benefit China-DPRK relations because it would “help to reduce certain abnormalities in the relationship between the [Korean] population and the Chinese volunteers” which were associated with “breaches of military discipline on the part of the latter”. See “Dnevnik Posla SSSR v KNDR A. M. Ivanova za period s 14 do 20 Dekabrya 1957 Goda”, in archival material from the state archives of the former Soviet Union, held by the Jungang Ilbo newspaper, Seoul; file no. 57-4-1-3, entry for 20 December 1957.

[34] Ben Evans, Out in the Cold: Australia’s Involvement in the Korean War – 1950-1953, Canberra, Commonwealth Department of Veterans Affairs, 2001, p. 89.

[35] Explanatory panel in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009.

[36] Explanatory panel in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009.

[37] Department of External Affairs, Canberra, Departmental Dispatch no. 23/1949 from Australian Mission in Japan, “United Nations Commission on Korea”, 25 February 1949, p. 20, held in Australian National Archives, Canberra, series no. A1838, control symbol 3127/2/1 part 4, “Korea – Political Situation – South Korea”.

[38] Explanatory panel in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009.

[39] Explanatory panel in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009.

[40] Pak Wanseo, Three Days in That Autumn (trans. Ryu Sukhee), Seoul, Jimoondang International, 2001.

[41] Explanatory panels in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009. As the official history of the International Committee of the Red Cross points out, there was debate about including such a clause in the 1949 Geneva Conventions, but in the end it was shelved. The Conventions include a statement that sick and injured prisoners-of-war may not be repatriated against their will while hostilities are continuing, but in relation to repatriation after the end of a war, state only that “prisoners of war shall be released and repatriated without delay after the cessation of active hostilities”; see Catherine Rey-Schyrr, De Yalta à Dien Bien Phu: Histoire du Comité internationale de la Croix-Rouge, 1945-1955, Geneva, International Committee of the Red Cross, 2007, p. 276; also “Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War,” on the website of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (accessed 16 June 2009).

[42] Explanatory panel in the Australian War Memorial, viewed 14 June 2009.

[43] Bleiker and Hoang, “Remembering and Forgetting the Korean War”, op. cit., p. 212.