Refugees, Abductees, “Returnees”: Human Rights in Japan-North Korea Relations

Tessa Morris-Suzuki

From North Korea to Japan

At 4 o’clock in the morning on 2 June 2007, a man out fishing near the port of Fukaura in Japan’s Aomori Prefecture came upon a small boat with four people in it. The boat had left the North Korean port of Cheongjin one week earlier, and the people on board – a couple and their two adult sons – were North Korean refugees. [1] They were the first to appear on Japan’s shores by boat since 1987, when eleven refugees from North Korea had arrived in Fukui on a boat called the Zu Dan 9082. The events in the sleepy little town of Fukaura briefly became headline news in Japan, igniting media debate about a possible impending influx of displaced people from the Korean Peninsula, and about the appropriate Japanese response to the North Korean refugee problem.

Repatriates arriving in Cheongjin

The four refugees told Japanese authorities that they had been heading from Cheongjin to Niigata (a route which, as we shall see, has interesting historical resonances), but had been carried north to the coast of Aomori Prefecture by the currents. However, even though their intended landfall had been Niigata, they were apparently not seeking asylum in Japan, but were instead asking to be resettled in South Korea.[2] After a brief detention in Japan, and a flurry of negotiations between the Japanese and South Korean governments, on 16 June the four refugees were shipped out of Japan to South Korea[3], and Japanese public interest in the incident subsided.

Fukaura police examine boat that contained North Korean refugees

In this paper, I want to use the arrival of that small boat as a starting point for thinking about the North Korean refugee issue (particularly as it relates to Japan), and more broadly for considering some aspects of the contentious problem of North Korean human rights.

For anyone concerned with human rights in Asia, the North Korean case presents an intractable problem, above all because it is one of the cases where human rights and political calculations have become most inextricably enmeshed. By almost any measure, the current regime in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) is a major violator of human rights. The problem is what the rest of the world can or should do about it.

For those (mostly on the right of the political spectrum) who advocate outside intervention to force regime change, the answer seems simple. North Korea’s human rights violations are their chief justification for demanding the use of pressure, or even of military force, to overthrow the current regime. Such intervention, they claim, would save many lives – the lives of those incarcerated in labour camps or facing malnutrition and possible starvation. At one level, this claim is probably correct, but (as I shall try to show in this paper) one does not need to probe very far into this rhetoric of human rights to find that it is riven with self-contradictions.

On the other hand, there are a large and growing number of people (among whom I would include myself) who believe that the use of outside threats or force to trigger regime change in North Korea would, in the long run, cause much more human suffering than it could relieve. Although the situations in North Korea and Iraq are in some ways very dissimilar, it is impossible to ignore the lessons of Iraq. There can be no doubt that the invasion of Iraq did save some – perhaps many – lives. There are people who would have died in Saddam Hussein’s prisons, but who survived because of the invasion. At the same time, however, it is equally clear that the invasion caused an even larger number of deaths, terrible human suffering, and a mass of new human rights problems. It is reasonable to suggest that outside-imposed regime change in North Korea would do the same, and that a gradual process of engaging North Korea in interaction with the region is the best way of allowing a lasting transition to a new and better social order.

The problem for those who take this view, though, is that it is very difficult to promote engagement with North Korea while also publicly condemning that country’s human rights violations, and it therefore becomes all too tempting to ignore these violations or sweep them under the carpet. The task of identifying alternative responses to the North Korean human rights problem – responses not linked to a hawkish political agenda – is an urgent and difficult one. In the pages that follow, I shall use a critical analysis of some Japanese debates on North Korean human rights as a basis for considering some aspects of this problem.

Beginning from the arrival of the four boatpeople in June 2007, I shall work backwards through history to explore some of the factors influencing Japan’s response to North Korean human rights issues. In the final section of the paper, I shall try to propose some possible new approaches which might at least help to address one practical problem: the plight of the small but growing number of people attempting or hoping to leave North Korea for Japan.

Victims or Secret Agents? Japan’s Response to North Korean Refugees

The arrival of the four boat people in Fukaura evoked a mixed response from the Japanese mass media. Much of the comment was sympathetic. Newspapers and TV commentators expressed astonishment that they had survived the dangerous voyage, and stressed the desperation that must have driven them to embark on their perilous journey. The Yomiuri newspaper’s front-page article noted that the refugees had brought poison with them to drink if they were caught by the North Korean authorities, and quoted them as saying that they were fishermen, and that they had “left North Korea because life was so hard.”[4] The Asahi’s editorial called for tighter border controls and for dialogue between the region’s countries to develop a framework for receiving refugees. But it also reminded readers that more than one hundred North Korean refugees are already living in Japan, and need greater assistance and support than they had received so far.[5]

However, particularly after it was revealed that one of the two young men on the Fukaura boat had been carrying a small amount of amphetamines, some of the public commentary turned more hostile. In late June, the rightwing Sankei newspaper invited its readers to respond to a series of questions about Japan’s policy towards North Korean refugees, one of which was “should those who want to stay in Japan be recognized as economic refugees?” 68% of respondents to this question said “no” and only 32%, “yes”. Since the respondents were a self-selected group of Sankei readers, their views cannot be seen as representing Japanese public opinion, but the comments they submitted to the newspaper shed an interesting light on the range of emotions evoked by the arrival of North Korean refugees. One self-employed man in his sixties posed the questions: “Are they really refugees? Are they really a family? Maybe they’ve been sent as secret agents [kosakuin] posing as refugees. Has this been checked properly?” Others made a similar point, a white-collar worker in his 30s, for example, writing: “on no account should they be accepted as economic refugees. There is a high probability that some of the people who claim to be refugees are really secret agents. Besides, the Japanese government and the Japanese people lack the mental space and preparedness [seishinteki yoyû to kakugo] to accept economic refugees”.[6]

Repeated reference to “secret agents”, of course, reflects the way in which the refugee issue is intertwined in the popular imagination with the abductions of at least 13 Japanese citizens by North Korean agents during the 1970s and 1980s. (The North Korean government admits to 13; the Japanese government claims that the number is at least 17).[7] The wellsprings of the fear and suspicion expressed by the Sankei readers can better be understood if we consider an interesting commentary on the arrival of the four boatpeople by Araki Kazuhiro, a professor at Takushoku University who also heads the Investigation Commission on Missing Japanese Probably Connected to North Korea [Tokubetsu Shissosha Mondai Chosakai, commonly known in Japanese as Chosakai for short]. The Chosakai is one of a cluster of closely linked and highly influential lobby groups campaigning for action on the abduction issue. Its main role is to investigate hundreds of unsolved missing-person cases stretching back as far as 1948 in search of evidence that they were abductions by North Korean agents, and its energetic detective work has produced estimates of the number of kidnap victims which range as high as 470.[8]

Araki begins his report on the arrival of the refugees by pointing out that the stretch of Aomori coastline where the boat arrived is “a mecca for landings by secret agents”:

“people from the mass media who visit the fishermen’s houses that line the shore are surprised to find that houses everywhere contain letters of thanks from the police. As I discovered from experience, everyday conversations there are full of stories about such things as discovering radios or equipment bags belonging to [North Korean] secret agents, and handing these in to the police”.[9]

Having set the scene with this image of sinister visitations, he goes on to concede that “it seems the four people are not secret agents, but even if they are refugees, I can’t help feeling that something is afoot”. Recalling a prediction he first reported fifteen years ago, Araki cites an estimate by the former head of Japan’s Immigration Control Agency, Sakanaka Hidenori, that economic and political crisis in North Korea might generate a wave of 300,000 refugees sweeping, tsunami like, onto Japan’s shores. This prediction, as Araki explains, is based on the fact that, between 1959 and 1984, 93,340 people – mostly ethnic Koreans residents in Japan [Zainchi Koreans] but including over 6,000 Japanese citizens – took part in a mass “repatriation” from Japan to North Korea (the details of which are described in greater detail in a later section of this paper). The experience of these “repatriates” [kikokusha][10] has generally been very difficult, and it is reasonable to assume that a large number may now want to go back to Japan. Araki agrees that Japan should respond to demands from former repatriates who seek re-entry to Japan, but the overall message of his article is that “the only way to stop ordinary North Koreans from arriving as refugees is ultimately to replace the Kim Jong-Il system and create a better regime.” He concludes by summarizing the Chosakai’s view of the boatpeople as follows:

I imagine that there will be a growing number of people in Japan who will say, “let’s drive out all the refugees!’ Of course, we are opposed to this view, but we hope that those who feel alarmed by the refugees will start saying “in that case, let’s bring about regime change as soon as possible!’”[11]

Araki’s image of hundreds of thousands of North Korean refugees poised to descend on Japan is echoed in other quarters. A government security think-tank has proposed the slightly more modest estimate of 100,000 to 150,000.[12] These predictions seem to me extremely far-fetched. However, it is undoubtedly true that some of the Cold War era repatriates would like to return to Japan, where many still have relatives. The refugees already resettled in Japan, and alluded to in the Asahi editorial on the Fukaura incident, are in fact all people who took part in the Cold War migration from Japan to North Korea or dependents of these repatriates.[13] The arrival of these repatriate-refugees [dappoku kikokusha], who have trickled into Japan over the past decade or so, has been almost entirely unheralded by the media, since they came not by boat but (in most cases) on flights from Beijing or other Asian cities arranged with the help of Japanese diplomatic missions. Their precise number is uncertain, because there is no official resettlement scheme and no figures are published by the government, but newspaper reports estimated the number in early 2009 at around 170.[14] It seems very possible that, with accelerating social and political change within North Korea, the number seeking resettlement in Japan may rise to several thousand, and this fact makes the question of Japan’s response to the refugee problem an important and pressing one.[15]

Yet, as commentators on the refugee issue have pointed out, the Japanese government has yet to define any clear policy on North Korean refugees. Some of the refugees already in the country are Japanese citizens, and those without Japanese nationality have not been granted asylum under the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees, nor under Japanese national law. Rather, they have been allowed to remain in Japan through a discretionary act of the Japanese Ministry of Justice. The government’s response to arrival of the four boatpeople was likewise entirely ad hoc. Lawyer ÅŒhashi Tsuyoshi argues that the most appropriate course of action would have been to treat them as asylum seekers and assess their claims according to the norms of the Geneva Convention on the Status of Refugees, to which Japan is a signatory, but this did not happen. Instead, the four North Koreans were held in police “protection”, using a law normally applied to runaway children, and then shipped out to South Korea.[16]

In fact, though a new law passed in 2006 (and commonly referred to as “North Korea Human Rights Act”) commits the Japanese government to developing a policy on the refugee issue, nothing has so far been done to put this intention into practice.[17] The arrival of the boatpeople indeed casts interesting light on the paradoxes inherent in the new law. The legislation’s full title is “The Law on Countermeasures to the Abduction Problem and other Problems of Human Rights Violations by the North Korean Authorities” [Rachi Mondai sono ta Kita Chosen Tokyoku ni yoru Jinken Shingai Mondai e no Taiko ni kansuru Horitsu. It will be referred to below as the North Korea Abduction and Human Rights Law]. Although it is in some respects modeled on the US North Korea Human Rights Act of 2004, the law’s cumbersome title suggests just how much the Japanese version is driven by the agenda of the abduction problem, which has become the central issue in Japan’s relationship with the DPRK.

The law focuses mainly on detailing the pressures to be placed on North Korea to resolve the abduction issue. Article Six commits the Japanese government to “endeavouring to establish measures related to the protection and support of North Korean refugees [dappokusha]”[18], but is very short on specifics. The only elaboration of this is a statement that Japan will cooperate closely with foreign governments, international organizations and “non-governmental organizations [minkan dantai] both at home and abroad” to address the problems of abductees, refugees and other victims of North Korean human rights abuses. The failure to come up with anything more concrete than this, despite massive criticism of North Korea’s human rights record in Japanese media and political circles, reflects internal contradictions that we have already glimpsed in Araki Kazuhiro’s commentary on the arrival of the boat people.

The North Korean Crisis and the Rise of “Human Rights” Nationalism in Japan

To understand these internal contradictions, it is necessary to look a little more closely at the political environment which framed the emergence of Japanese media debate on the North Korean human rights issue. The language of human rights is of course protean, always pulled between one political pole and another, as each side seeks to claim it for its own. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, though some Marxists discounted the notion as bourgeois window dressing, the concept of human rights can generally have been said to have been more widely used as a political ideal by the Left than by the Right. Human rights activists in Japan, for example, battled for workplace equality for women and minorities, opposed the fingerprinting of foreign residents and lobbied unsuccessfully for the abolition of capital punishment. In the process, they were sometimes criticized for attempting to impose an inappropriate alien ideology on Japanese society.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, the language of human rights (not only in Japan but also elsewhere) came to be more widely used by Right as well as Left, and was increasingly used to justify military interventions in countries which were deemed to fail international humanitarian standards. German academic and politician Uwe-Jens Heuer described this trend as the rise of “human rights imperialism”, which he saw as being characterized by an “instrumentalization of human rights”. A key feature of this process, according to Heuer, was that the discourse of human rights became separated from international law. Rather than respecting and implementing the rights embodied in international charters, powerful countries used military force to punish weaker states which failed to respect human rights, with these rights themselves being unilaterally and selectively defined by the powerful.[19]

In the Japanese context, I want to trace a phenomenon related to, though somewhat different from, the trends discussed by Heuer. I call this phenomenon the rise of “human rights” nationalism. The phrase “human rights” is in quotation marks because, as shall argue, although this ideology makes extensive use of the rhetoric of human rights, its recognition of rights is highly selective, and its underlying logic is in fact one of “protection” rather than of “rights”. In “human rights” nationalism, the emotions of humanitarianism become instrumentalized in the service of national security. Anxiety about the destiny of one’s own nation comes to be focused on a particular external force – a foreign nation, an alien ethnic group etc. – which is seen both as radically threatening to national security and as violating key human rights. Thus nationalism and human rights are fused into a single ideology which has great emotional appeal.

But the problem is that (like Heuer’s “human rights imperialism”) this ideology is not based on respect for the international laws and institutions which (however imperfect they may be) provide the foundations for the long-term maintenance of human rights. Instead, “human rights” nationalism focuses selectively on particular humanitarian concerns that happen to overlap with national security concerns. Even more importantly, in this ideological fusion, it is always human rights that are made the instrument of the security of the nation-state, not the other way around. So, in any situation where the interests of human rights diverge from the interests of national security, it is always the former that are sacrificed to the latter.

“Human rights” nationalism is specific neither to Japan nor to the 1990s. It has existed ever since the concepts of nationalism and human rights first appeared. It should be emphasized that other strands of human rights discourse in Japan have continued to flourish outside the restricting framework of “human rights” nationalism, as illustrated by the work of social movements like the Solidarity Network with Migrants Japan (SMJ), which supports the rights of foreign residents in Japan, and the Violence Against Women in War Network (VAWW-Net), which campaigns for redress to former victims of wartime sexual abuse by the Japanese military (the so-called “comfort women”). It is also clear that “human rights” nationalism is not the only possible approach to the problem of human rights in North Korea. For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on North Korea, Vitit Muntarbhorn, has developed a critique which focus on the need for the DPRK to abide by international human rights law, while also emphasizing that other countries should seek to engage North Korea in dialogue and provide humanitarian and development aid.[20]

However, I shall argue that a particular form of “human rights” nationalism has become very influential in Japan since the mid-1990s and into the twenty-first century, and that this was focused on the threatening image of a destabilized North Korea. The continuing influence of this “human rights” nationalism is a crucial source of the difficulties which still beset public responses to the North Korean refugees today.

Several factors created the environment for the rise of this variant of nationalism in 1990s Japan. One, of course, was the collapse of the Communist bloc and the growing evidence of extreme poverty and political repression in the remaining Stalinist state, North Korea. But other factors were also at work, including the political fluidity in early 1990s Japan, and the changing relationship between Japan and its other neighbours, particularly South Korea and China. Domestically, a major split in the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party led to the formation of a series of short-lived coalition governments, and created uncertainty about the directions of Japan’s political development. Regionally, meanwhile, South Korea had become a highly industrialized country, and was in the midst of a rapid process of democratization, while China’s embrace of economic liberalization was beginning to bear fruit. One important aspect of the changes in Japanese domestic politics and in the regional balance of power was the resurgence of debates about historical responsibility, which led to a series of significant apologies by Prime Ministers Hosokawa and Murayama for past wrongs committed by the Japanese state. The controversies surrounding these apologies can, in retrospect, be seen as having had an important effect on emerging perceptions of the abductions and the North Korean human rights issues.

The first people to put the abduction issue into the public arena were a group of researchers and politicians, many of them originally associated with the Democratic Socialist Party [Minshato], a small party which was dissolved in 1994. The politicians included ÅŒguchi Hideo (now an opposition Democratic Party parliamentarian and prominent member of the National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Kidnapped by North Korea, NARKN, known in Japanese as Rachi Higaishi o Sukuu Kai, or just Sukuu Kai for short) and Nishimura Shingo (who was forced to resign from a junior ministerial post in 1999 after advocating Japan acquisition of nuclear weapons, and is currently a Democratic Party parliamentarian). To give some sense of their human rights discourse, however, I shall focus particularly on three prominent North Korea human rights activists, all of whom are researchers and public commentators associated with the Modern Korea Institute [Gendai Koria Kenkyûjo]. This organization was originally established in 1961 under the title the Korea Research Institute [Chosen Kenkyûjo]. The activists whose work I shall discuss here are Sato Katsumi, who has been a key figure in the Institute since 1964; Araki Kazuhiro, who became head of the research section of the Institute in 1993, and (as we have seen) subsequently also became director of the Chosakai; and Miura Kotaro, who, with Sato, co-edited the Institute’s flagship journal Modern Korea, while also heading a human rights NGO: the Society to Help Returnees to North Korea [Kita Chosen Kikokusha no Seimei to Jinken o Mamorukai, or Mamorukai for short].

Sato and Araki come from very different intellectual and ideological backgrounds. Sato, who was already in his sixties by the 1990s, had been a well-known left-wing researcher and activist, and had spent much of his early life advocating closer ties between Japan and North Korea, as well as working to improve the human rights of the Korean community in Japan. As a Communist Party member and official of the Niigata Branch of the Japan-Korea Association [Niccho Kyokai], he was from 1960 to 1964 actively involved in promoting and organizing the mass repatriation of Koreans from Japan to North Korea.[21] He joined the Chosen Kenkyûjo in 1965, and by the mid-1970s had become one of its leading members. By the late 1970s, however, Sato’s political stance was changing, and growing splits were appearing in the ranks of the Institute.

Sato Katsumi’s disillusionment with Communism began to become evident after a visit to China during the final stages of the Cultural Revolution.[22] By this time, he was also beginning to become aware of the fate of the repatriates, most of whom suffered great poverty and hardship after their arrival in the DPRK, and thousands of whom were ultimately sent North Korean labour camps. This realization left Sato in the painful position of feeling himself to be both a betrayer (because he had sent others to a terrible fate) and betrayed (by the Communism and North Korean Juche ideology which had believed, but which had proved so desperately flawed). “Sadly,” he wrote, “the substance of the first several decades of my involvement with Korean issues has been totally negated by reality.”[23] Such experiences help to explain the intense personal anger towards North Korea that permeates much of Sato’s writing.

From the 1980s on, his writings on North Korea came increasingly to highlight the violent and oppressive nature of the DPRK and the widening gaps between the comfortable life of the political elite and the sufferings of ordinary people.[24] At the same time, other aspects of the rightward shift in Sato’s views became visible. For example, after the 1980 Kwangju Uprising against the Chung Doo-Hwan dictatorship in South Korea, whose suppression involved a large-scale massacre of civilians by the South Korean military, Sato criticized human rights groups in Japan for circulating what he claimed were invented stories of military brutality in Kwangju. He also condemned Japanese supporters of the imprisoned South Korean opposition politician (later to become President) Kim Dae-Jung for in effect providing encouragement to North Korean ambitions.[25] The result was an irrevocable split between Sato and other members of the Korea Research Institute which led to the demise of the old organization and its reappearance in 1984 as the Modern Korea Institute, led by Sato with the assistance of a small band of like-minded activists.

The transformation of Sato’s ideology was not simply motivated by increasing awareness of economic collapse and political repression in North Korea; nor was it a simple extension of his earlier human rights concerns to abuses north of the 38th parallel. Rather, this ideological transformation was one which SatÅ himself explicitly linked to the emergence of a post-Cold War order. The collapse of communism and the rapidly evolving political situation in South Korea, he argued, was resulting in a gradual political rapprochement between North and South Korea. Whereas Japan and South Korea had previously been able to unite against the “common enemy” – the DPRK – now North and South Korea were not only engaging in dialogue, but even joining in condemning Japan for issues such as its failure to address issues of historical responsibility, most notably, the “comfort women” issue.

In August 1993, Japan’s coalition government completed an investigation into the institutionalized sexual abuse of women in military “comfort stations” [ianjo] during the Asia Pacific War. The report acknowledged that many thousands of women had experienced terrible suffering in the “comfort station” system, and that the Japanese military had been involved in their recruitment. In response to the findings of the report, Chief Cabinet Secretary Kono Yohei issued a public apology on behalf of the Japanese government.

The report and apology attracted impassioned criticism from Sato Katsumi, who viewed it as evidence of a dangerous shift in the power relationship between Japan and the two Koreas. Japan, Sato warned, was suffering from a dangerous “apology disease”, and its statements of regret for the past were placing it in a “subordinate” position to North and South Korea. More alarmingly still, apologies (he warned) were likely to encourage both Koreas to join in demanding monetary compensation, re-opening issues which (in the South Korean case) were supposed to have been resolved by the payment made when Japan normalized relations with the Republic of Korea in 1965. [26]

Sato’s vision of Japan’s imperiled national prestige and security brought his views into close alignment with those of the much younger Araki Kazuhiro, who joined the Modern Korea Institute in 1993. Araki’s father had trained during the war in the Manchukuo Military Academy alongside a man then known as Takaki Masao, who (under his real name, Park Chung-Hee) was later to become President of the Republic of Korea (ROK). This connection had a lasting influence on the younger Araki, who wrote his graduation thesis on Park, visited South Korea on a number of occasions during the last years of the Park dictatorship, and still cites Park as one of the two people whom he most admires.[27]

Araki initially seemed to be headed for a career in politics. He joined the Democratic Socialist Party 1979 and became secretary-general of its youth branch, before running as an independent for a seat in the Lower House of parliament in 1993.[28] Thereafter he embarked on a career as a researcher in the Modern Korea Institute and at Takushoku University, while pursuing political activism through a variety of groups including the Chosakai – created in 2003 as a “sister organization” of the better known Rachi Higaishi o Sukuukai (National Association for the Rescue of Japanese Kidnapped by North Korea, generally known in Japanese by the abbreviation Sukuukai). Araki has also established his personal security think-tank, the Strategic Intelligence Institute Inc. [Senryaku Joho Kenkyûjo KK], and lists one of his current positions as “Opinion Leader for the Office of the Inspector General, Eastern Section, Ground Self-Defence Forces” [Rikugun Jieitai Tobu Homen Sokanbu Opinionrîda][29], a role could be regarded as somewhat alarming, given that one of the Chosakai’s current objectives is to “seek to foment outside opinion and create the conditions within the Self Defence Force” for direct intervention by the Japanese armed forces to rescue Japanese abductees in North Korea.[30]

By the mid-1990s, Araki had become a fairly high-profile public commentator on Korean affairs, and particularly on the increasingly dire state of affairs in North Korea. After the death of Kim Il-Sung in 1994, there was much speculation about the future of the DPRK. Amidst uncertainly about the succession of Kim Jong-Il, and growing evidence of economic collapse and impending famine, Araki published a book and a series of articles predicting not only the impending collapse of the regime but also an armed attack on South Korea by a desperate North Korean military. This attack, he suggested, would take the form of a Blitzkrieg strike on Seoul, whose main aim would be to destroy South Korea’s political and economic infrastructure and take hostage large numbers of South Koreans and foreign residents. The South Korean military and US troops based in the South, he believed, would probably be unable to respond effectively because South Korean student and opposition groups had been infiltrated by tens of thousands of North Korean agents, who were waiting to act on orders from Pyongyang “as they did during the Kwangju Incident.”[31]

Meanwhile, from about 1996 onward both Araki and Sato, together with a group of politicians including ÅŒguchi Hideo and Nishimura Shingo, had also taken up the cause of a number of Japanese citizens who had mysteriously disappeared, and were believed to have been kidnapped by North Korea. In the early stages, Araki’s writings particularly highlighted the cases of two thirteen-year-olds – Yokota Megumi, who had vanished while returning home from badminton practice in the city of Niigata in 1977, and Terakoshi Takeshi, who together with his two uncles Terakoshi Sotoo and Shoji, had disappeared while on a fishing trip off the coast of Ishikawa Prefecture in 1963.[32] Takeshi and Sotoo were actually known to be in North Korea, because fourteen years after their disappearance, their family in Japan had finally received a letter from Sotoo, informing them that Shoji had died, but that he and Takeshi were living DPRK.

While the story of Yokota Megumi was to became the most internationally notorious of all the abduction incidents, the Terakoshi case subsequently disappeared from most public accounts of the abductions, in part at least because the victim failed to behave in the way that the Japanese media and support groups expected an abductee to act. Despite considerable circumstantial evidence that he was indeed taken to North Korea against his own will[33], Terakoshi Takeshi, who had since become a senior union official in North Korea and changed his name to Kim Yeong-Heo, has consistently denied that he was abducted. He made a short visit to his old home in Japan soon after Koizumi’s trip to Pyongyang in 2002, but has remained living in Pyongyang.[34] Meanwhile, however, the Modern Korea Institute had begun to investigate other possible abductions by North Korea. By the late 1990s the issue came to prominence, and public interest was reached fever pitch in 2002, after the Kim Jong-Il regime admitted to having kidnapped 13 Japanese, but stated that eight (including Yokota Megumi, who was claimed to have committed suicide) were now dead.

In other circumstances, the “human rights” nationalism developed by figures like Sato and Araki in the 1990s might have remained just one of many contesting streams in Japanese political discourse. But the shockwaves created by the revelations about the abductions gave the views of the Modern Korea Institute, Sukuukai and their associates an extraordinary influence both on media debate and on Japanese diplomacy: an influence further inflated as a growing number of ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) politicians including Abe Shinzo made the abduction issue a central plank of their political agenda. Fear of North Korea, it may be noted, is a major factor in winning public support for the substantial expansion of Japan’s military capabilities since the early 1990s – a process which one observer has termed “Heisei Militarization”.[35] From this perspective, the close connection of abduction activists like Araki with the Self-Defense Forces seems to be more than mere coincidence.

The abduction issue had an unprecedented influence on public opinion. Many ordinary people who had never been involved in politics or NGO activism before rallied to the cause because they were genuinely moved at the terrible plight of the abductees and their families: particularly of Yokota Megumi’s parents, who had experienced a particularly bizarre and agonizing version of every parent’s worst nightmare. This was, par excellence, an issue where concern for human rights and for national security coincided. As Sato Katsumi stressed, in carrying out the abductions, North Korea had violated both Japanese sovereignty and the most fundamental of human rights.[36] However, the Modern Korea Institute’s passion for human rights was now wholly focused on those human rights abuses which were simultaneously threats to national security. In the process, its commitment to human rights suffered a strange bifurcation. Sato’s pursuit of justice for the abductees, for example, went hand-in-hand with his equally vocal opposition to compensation for former “comfort women”, while Araki’s went hand-in-hand with his active involvement in the campaign to prevent Japanese local governments from granting voting rights to foreigners.[37]

“Human Rights” Nationalism and the Refugee Issue

But it is in relation to the issue of North Korean refugees that the internal contradictions of “human rights” nationalism become most evident. The critique of North Korea’s human rights record, after all, demands sympathy towards those who flee the country in search of a better life elsewhere. But national security (as envisaged by nationalist commentators) demands tight border controls and a wary, if not hostile, attitude to outsiders who seek entry into Japanese society.

During the 1990s, in his commentaries on the North Korean military threat, Araki Kazuhiro began to cite the suggestion from “a senior Ministry of Justice Official” (whom he later identified as Sakanaka Hidenori) that a possible 300,000 former “repatriates” from Japan and their families might flee a collapsing North Korea and arrive in waves on Japan’s shores.[38] As time went on, Araki’s predictions on the subject became more alarming. In March 1999, following an incident when the body of a dead North Korean soldier was washed ashore in Japan, he wrote an article in which he recalled the arrival of the North Korean refugee boat the Zu Dan 9082 in 1987:

It is said that, if the North Korean system should collapse, possibly as many as 300,000 refugees would eventually flow into Japan. If the political instability within North Korea continues, some of them will arrive on Japan’s shores not as dead bodies but as second and third Zu Dans. In the worst case scenario, they may arrive carrying weapons.[39]

The Japanese state (he insisted) should make urgent preparations for this alarming scenario; but it was entirely unclear whether the preparations Araki had in mind were plans to receive and help these victims of North Korean oppression, or defensive measures to drive armed intruders back into the sea.

Other members of the Modern Korea Institute, however, have over the years developed much more specific visions for a positive Japanese policy towards North Korean refugees. These visions stress the need for tight border controls, while also proposing – as part of a vision of Japan’s cultural uniqueness – measures to accept and assimilate certain types of refugee. In other words, they place acceptance of repatriate-refugees, alongside rescue of abductees, at the centre of their agenda. One of the most enthusiastic proponents of this vision is Miura Kotaro, chief representative of the Mamorukai: a group set up in 1994 to help those 93,340 ethnic Koreans and their Japanese spouses who were repatriated to North Korea during the Cold War era. Miura is also a key figure in the Tokyo branch of RENK [Rescue the North Korean People], the best known of the Japanese NGOs involved in the North Korean human rights issues.

From the late 1990s onwards, the Mamorukai has become increasingly active in supporting returnee refugees. Together with other groups such as the Sukuukai and Chosakai, it lobbied the government to include support for refugees (as well as investigation of suspected abduction cases and tough sanctions against the DPRK) in the 2006 North Korea Abduction and Human Rights Law. Shortly after the law was passed, and again immediately after the arrival of the four North Korean boatpeople in June 2007, Miura Kotaro published articles spelling out his thoughts on the future of Japanese policy towards North Korean refugees.

In the first of these articles, Miura begins by making a clear distinction between returnee-refugees, whom Japan should accept for resettlement, and other North Korean refugees, to whom Japan (he believes) does not have a responsibility. Miura’s argument is that returnee-refugees should be accepted and helped, above all, because they perceive Japan as their true homeland [kokyo]. Indeed, he emphasizes that the homeland for which they long is not so much the real Japan of the twenty-first century as the long-lost and more innocent Japan they left in the early 1960s. In this sense, the returnee-refugees are depicted not only as true Japanese at heart, but as embodiments of a pure Japaneseness that some young Japanese of today have lost: “Surely we should welcome as Japanese nationals the returnee-refugees, who are demanding to return, settle and be ‘assimilated’ into Japan: or more precisely, are demanding to ‘return’ to the Japan of the early 1960s, the age when Japan still retained its local and family communities.”[40]

This desire for “assimilation” into a vanishing traditional Japan seems to make the returnee-refugees an ideal test case for what Miura (borrowing a term from French historian Emmanuel Todd) calls “open assimilationism”.[41] Rejecting the multiculturalist notion of “the right to difference”, which (he argues) has only caused social division and inter-ethnic tension, Miura proposes that Japan should develop its own unique brand of “open assimilationism”, which may serve as a model for other nations currently beset by ethnic conflicts.

To realize this vision, Miura proposes a series of practical steps, which begin at the point where former returnees and their families make the dangerous crossing of the border out of North Korea and into China. At present, the refugees are often forced to remain in hiding in China for months while they contact relatives in Japan to obtain papers, make contact with Japanese diplomatic missions in China, and wait for permission to leave China and enter Japan. This wait is a time of great anxiety, since discovery would mean being returned across the border to probable incarceration in a grim North Korean prison.

Miura’s first proposal, then, is that Japanese consulates in the relevant parts of China should expand the facilities (already in existence in some diplomatic missions) where refugees can live for several months while their claims to be former returnees are checked. The checking, Miura emphasizes, should be extremely rigorous, so as to weed out “bogus returnee-refugees” and secret agents, and should include DNA tests to ensure that those who claim to be families are actually related to one another. While in the Consulate, refugees should be given information and advice about Japan, to be provided in part by Japanese NGOs. This should include warnings that life will be difficult, and that they will receive greater material support if they choose to resettle in South Korea rather than Japan.

Those who nonetheless choose to go to Japan should be accepted and given various forms of assistance, including government-supported help in finding work and housing. They could also be granted livelihood protection payments (the relatively small welfare payments available to the destitute in Japan) for up to a year or a year-and-a-half. However, Miura emphasizes the dangers of welfare dependence, and therefore believes that these payments should be made only on condition that the refugees initially live in a closed training facility, which Miura calls a “Japanese-style Hanawon”. The controversial Hanawon in Anseong, south of Seoul, is a South Korean processing and resettlement center, where refugees from North Korea are kept separated from the rest of society for two months while they are trained in work and social skills.[42] Miura’s proposed “Japanese Hanawon” seems a more far reaching project, since he envisages refugees remaining there for at least six months, while NGOs (supported by government) provide them with language and skill training, counseling and education in “the rules of life in a democratic society”.[43]

Language training is particularly strongly emphasized, not simply for practical reasons, but because Miura sees language as the vehicle through which the refugees will acquire a knowledge of Japanese “rules, customs, behaviour patterns, social relationship structures etc.” Therefore, “study and mastery of the Japanese language” [Nihongo gakushu to shutoku] is defined as a duty for all refugees, and as a prerequisite which they must fulfill if they are to receive Japanese citizenship or permanent residents rights.[44]

Miura concludes his essay on the subject by quoting from the postwar Shintoist writer Ashizu Uzuhiko, who called for a revival of Japanese ethnic tradition centred on the emperor, and on a positive re-evaluation of Japan’s prewar and wartime Pan-Asianism. Unlike many nationalists, Ashizu saw the acceptance of immigrants as part of Japan’s imperial tradition. Reviving the phrase (much used in the wartime empire) “All the Four Corners of the World Under One Roof” [hakko ichiu], he presented migration as a way of enhancing Japan’s international status and gathering people from around the world under the protection of the Emperor, and he claimed that “ever since the Meiji period Japan has led the world in emphasizing racial equality and freedom of migration.”

“When the issue of allowing the entry of returnee-refugees faces various difficulties, “comments Miura, “I always think of these words”.[45]

The practical activities of the Mamorukai, and of Miura himself, have undoubtedly provided many repatriate-refugees in Japan with much-needed and welcomed practical support. Indeed, the limited support available to the refugees already in Japan comes mainly from NGOs like the Mamorukai and the more recently created Japan Aid Association for North Korean Returnees [Kikoku Dappokusha Shien Kiko], established in 2005 by the former head of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau, Sakanaka Hidenori. For Sakanaka, as for Miura, support for the repatriate-refugees is part of a larger political agenda. Sakanaka sees this as the final remaining issue in his lifework – “solving the problem of Zainichi society” [“Zainichi shakai” no mondai kaiketsu].[46] Both as a senior official of Japan’s Immigration Control Bureau and since his retirement in 2005, Sakanaka has argued energetically for a more open Japanese policy towards immigrants, and for measures to make it easier for Korean and other foreigners in Japan to become Japanese nationals. Like Miura, Sakanaka presents greater openness to foreigners as a strategy for enhancing national power and prestige, arguing that large-scale future immigration is the only way to maintain Japan’s economic, cultural and political strength in an age of falling birthrates.

In terms which in some ways echo Miura’s notion of “open assimilationism”, Sakanaka therefore calls for “Japanese style multicultural coexistence” as the only way to maintain a “big Japan” (as opposed to the “small Japan” threatened by population decline).[47] Many of the practical measures he proposes (such as changes to the nationality law to make naturalization easier, and the creation of an anti-discrimination commission) would indeed enhance the rights of migrants to Japan. But this vision, too, is underpinned less by a logic of the rights of migrants, than by a logic of national security. Implicitly at least, “desirable foreigners” [nozomashii gaikokujin] [48] are to be welcomed and protected as long as serve the aim of promoting a strong Japan, but are in danger of becoming “undesirable” the moment they cease to serve that aim.

Since the North Korea Abduction and Human Rights Law stresses government cooperation with NGOs in dealing with refugee issue, future refugee support policies are also likely to involve a large role for these NGOs. However, the political ideals behind the NGOs we have examined raise some important concerns. Though there is no question that these groups work with energy and dedication to assist refugees in Japan, and their support is welcomed by the refugees themselves, the reliance of the refugees on a small group of NGOs with distinctive socio-political agendas is a source of concern, particularly if we consider the issue against the historical background of the repatriation which took Korean and Japanese migrants from Japan the North Korea in the first place.

From Japan to North Korea, c. 1960

Recalling his own involvement in the mass relocation of ethnic Koreans from Japan to North Korea, Sato Katsumi has described how a movement demanding repatriation emerged from within the Korean community in August 1958, clearly promoted by the North Korean government itself. The movement, however, spread quickly, and was soon also taken up by the mainstream Japanese media, public intellectuals and some of Japan’s leading politicians.[49]

There is, in fact, an ironic similarity between the wave of media emotion generated by the repatriation movement in 1958-1959 and the even greater emotion evoked by the story of the abductions from 2002 onward. Both issues involved powerful stories of human suffering. In 1958 and 1959, for the first time since the end of the Asia-Pacific War, Japanese national newspapers were full of accounts of the individual hardships faced by Koreans in Japan, and (as the date for the departure of the first repatriation ship approached) media reports repeatedly highlighted the deep desire of the departing Koreans to see their native land again.[50] As in the case of the abductions (though for different reasons) there were genuine problems of human rights at stake. Also as in the case of the abductions, the human rights dimensions of the issue happened precisely to coincide with a widely accepted understanding of the interests of Japanese national security. Many media articles at the time pointed out that repatriation to North Korea, while satisfying the heartfelt longing of Koreans to “go home”, would simultaneously remove from Japan a group of people who were widely viewed as being left-wing and a source of social disruption.

Sato argues that the originators of the repatriation scheme were the government of the DPRK and the Pro-North Korean General Association of Korean Residents in Japan [Chongryun], and that Japanese politicians were lured into supporting this disastrous plan by the enthusiasm and skilful propaganda of its North Korean proponents.[51] However, recently declassified documents show that the background to the repatriation movement was much more complex than had previously been realised by most people – even by those like Sato who had been personally involved in the events of the time. In fact, as early as 1955, some senior bureaucrats and politicians in the ruling Japanese Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had quietly taken up the idea of promoting a mass exodus of ethnic Koreans from Japan to North Korea. They sought to promote this migration via the intermediary of the international Red Cross movement, so as to avoid the political repercussions which might ensue if it was seen as being a Japanese-promoted scheme.[52] A major motive for their support of a mass migration to North Korea was the perception of Koreans in Japan as potentially subversive and a burden on the welfare system.[53] On the Japanese side, a combination of carrots and sticks helped to make the prospect of migration appear attractive to Zainichi Koreans. The sticks included a clamp down on the very limited forms of welfare available to Koreans in Japan, and the explicit exclusion of all foreigners from newly-created national pension and health insurance schemes. The carrots complex secret negotiations to ensure international acceptance of the “repatriation” scheme, and a nationwide campaign by a Zainichi Korean Repatriation Assistance Association [Zainichi Chosenjin Kikoku Kyoryoku Kai], whose leading members included prominent politicians from across the Japanese political spectrum.

Boarding a ship for North Korea

The North Korean government was initially reluctant to accept a large inflow of Koreans from Japan, but in mid-1958 decided to promote the “repatriation” scheme for its own strategic interests, which included a need for labour power and technological know-how, and a desire to disrupt moves towards the normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea.[54] From then on, the Kim Il-Sung regime used a massive propaganda campaign to persuade Koreans in Japan that a better life awaited them in the DPRK. Chongryun, together with Japanese local government offices and the Japan Red Cross Society, became the main agent in carrying out the repatriation, and appears to have used pressure both to persuade some of the undecided to leave for North Korea, and to prevent the departure of those whose repatriation did not suit the North Korean government’s strategy. Meanwhile the US, although concerned about this mass migration from the “free world” to a Communist nation at the height of the Cold War, did nothing to prevent it because the Eisenhower administration was primarily concerned with maintaining good relations with the Japanese government, with whom it was then negotiating the revision of the US Security Treaty with Japan.[55]

It was against the background of these complex Cold War political maneuvers that tens of thousands of Koreans in Japan were persuaded to volunteer for resettlement in North Korea where, they were led to believe, a happier and more secure future awaited them. Elsewhere I have looked in more detail at the political forces behind the repatriation, and at its human consequences.[56] Here, however, I would like to consider just three aspects of the Cold War repatriation story which seem to me to have particular relevance to the refugee issue today.

Lessons from the Cold War Repatriation Project

One of the forces that helped turn the repatriation into a tragedy was, I believe, the fact that both Japanese and North Korean authorities tended to view the Korean “returnees” as an undifferentiated mass, and attributed to them certain stereotypical characteristics which fitted the strategic objectives of the governments concerned. To many Japanese politicians and bureaucrats, the repatriation project was aimed at “certain Koreans” whom they viewed as impoverished, left wing, disruptive and criminally inclined. To North Korean politicians and bureaucrats, on the contrary, they were oppressed compatriots whose terrible experiences in Japan had given them a burning desire to help build the socialist homeland. Needless to say, neither of these stereotypes even began to capture the diversity of personalities, experiences, hopes and motivations that characterized the 93,340 people who ultimately left Japan for North Korea.

Some were certainly poor; some had criminal records; some had experienced great hardship in Japan; a fair number were indeed filled with hope for the future possibilities of socialism. But they also included the rich and successful, the utterly a-political, and huge numbers of people whose main motive was the tentative hope that life in North Korea might be a little more secure than life in Japan. The homogenizing images imposed on returnees by both sides had far-reaching consequences. The stereotype held by Japanese officials explains the enthusiasm which some of them (including some senior official of the Japanese Red Cross Society) showed for maximizing the number of Koreans leaving Japan. The stereotype propagated on the North Korean side, meanwhile, helps explain the increasing mistrust and prejudice with which returnees came to be viewed as it became evident that they did not fit the expected model. Such misplaced expectations were undoubtedly one factor behind the increasingly repressive approach of the North Korean authorities to the people whom they had invited to “return to the socialist homeland”.

In the light of this experience, it seems particularly important that the same mistake should not be made again in relation to North Korean refugees (including repatriate-refugees) today. If the returnees themselves were an extremely diverse group, so too are repatriate-refugees. Though all have suffered the as a result of the collapse of the North Korean economy, some had nevertheless managed to live relatively stable lives in North Korea, while others have been victims of terrible political persecution. Some undoubtedly feel a sense of nostalgia for the Japan they left in 1960s or 1970s, but others (particularly the younger generation) have no memories of Japan at all. Some speak perfect Japanese and need no language training, while others (particularly the older groups of repatriate returnees, who are now in the 40s) may never be able to acquire really high levels of Japanese-language competence. Some are filled with passionate anger towards the North Korean regime because of their tragic experiences, while others have no interest in politics. Some, meanwhile, also feel that the Japanese government bears a large measure of responsibility for their fate.[57] Any effective response to the needs of refugees, then, must be able to encompass and respond to this diversity. Surely the last thing that the repatriate-refugees need is to become the test-case in yet another scheme for nationalist social engineering.

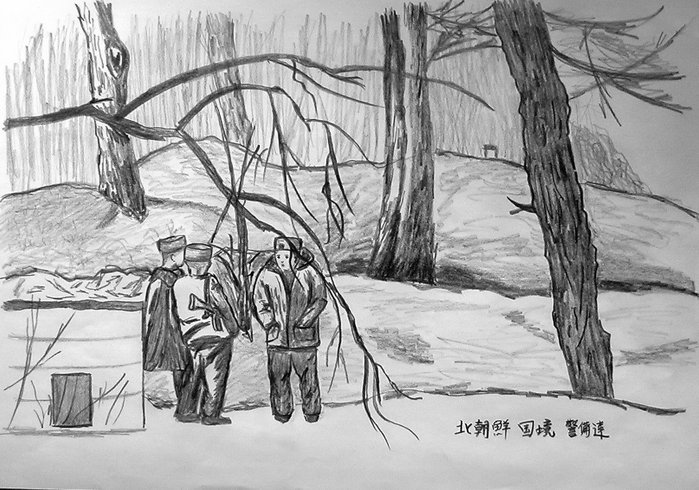

Border guards. Picture of the North Korean border drawn by a refugee

Another fundamental cause of the repatriation tragedy was the absence of legally enshrined rights for Koreans in postwar Japan. This in turn was a product of lacunae in both national and international law. Within Japan, ethnic Koreans, who had held Japanese nationality during the colonial period, were arbitrarily deprived of the right to that nationality in April 1952, when the San Francisco Peace Treaty came into effect. Since no alternative law was introduced to provide them with clearly defined permanent residence rights in Japan, they were left in a legal limbo which lasted for more than a decade. The normalization of relations between Japan and South Korea in 1965 provided some clarity to the position for those who registered and citizens of the Republic of Korea, but failed to resolve the problem for other Koreans in Japan. Testimony by returnees to North Korea, both at the time and since, shows that this sense of uncertainty was a key factor for many in determining their decision to leave Japan.

The sense of uncertainty was particularly great for the substantial group of Koreans in Japan (possibly in the region of 100,000 people or more) who had become “illegal entrants”: that is Koreans who had entered (or re-entered) Japan in the period after 1945. One aspect of this uncertainty was the fact that there was no reliable way for Koreans in Japan to obtain re-entry rights if they left the country (for example) to visit relatives in Korea. As a result, many made undocumented journeys out of and back into Japan, thereby becoming “illegal entrants” who, if discovered, were liable to internment in ÅŒmura Migrant Detention Center and repatriation to South Korea.

Picture of a North Korean village drawn by a refugee

This history is a reminder of the fact that rights enshrined in national and international law play a key role in protecting minorities, migrants and refugees. The problem with the current Japanese system for accepting repatriate-refugees is that it continues to rely on official discretion. Those re-entering Japan have no legally defined right to claim resettlement in Japan, or to claim support services when they arrive there. Meanwhile, the Chinese government refuses to accept the application of the Geneva Convention to North Korean refugees on its soil.

The approach to the refugee problem set out by Miura Kotaro includes some worthwhile proposals. It does seem important that Japanese diplomatic missions should be better prepared to respond to the needs of repatriate-refugees, and that those being resettled in Japan should be offered language classes, skill-training, counseling and help in finding housing and employment (though Miura’s vision of a “Japanese-style Hanawon” is problematic).

This approach, however, is in essence not a “human rights” approach at all, but rather a “state protection” approach. The concept of human rights is based on a belief in certain fundamental and universal rights, which exist in nature but can be effectively implemented only when they are enshrined in law. By contrast, the “state protection” approach is wary of the concept of rights, but encourages a benevolent state to give its protection to groups of people who fulfill particular criteria consistent with the aims of state security and power. State protection can indeed save lives, and make existence happier and easier for those whom the state defines as “good” immigrants or refugees.[58] But, as the history of Koreans in postwar Japan shows, it can also leave those who fail to serve the purposes of the state in a desperately vulnerable position, with tragic results.

In twenty-first century Japan, what will become (for example) of repatriate-refugees who do not feel nostalgia for the family values of 1960s Japan, and who find it difficult or impossible to master fluent Japanese? What will become of those who blame not only North Korea and Chongryun but also the Japanese government for their experiences over the past four decades? What of those who fail to fit the accepted image of the patriotic Japanese citizen or the “desirable alien”? What will become of refugees who may wish to come to Japan because their closest friends are there, but who fail to fit the definition of “repatriate-refugee”? All these questions point to the need for a new approach to the refugee issue: one that goes beyond the restrictive bounds of “human rights” nationalism.

Beyond “human rights” nationalism: Rethinking the Refugee Issue.

The political situation on the Korean Peninsula is, as I write, fluid and uncertain. It is impossible to predict the outcome of current movements towards the denucearization of North Korea, the normalization of relations between North Korea and the USA, and the signing of a peace treaty. But, however events unfold, it is very likely that the outflow of people across the border between North Korea and China will continue, and may increase in the next five to ten years. Though parallels with the end of the Cold War in Europe should be treated with caution, it would also be unwise to ignore the European experience of the large-scale documented and undocumented migration out of the former “Communist bloc” which accompanied the reintegration of East and West. If North Korea becomes more closely reintegrated into the region – both politically and economically – there seems a real likelihood that emigration will increase, adding to other expanding regional migration flows.

In Northeast Asia, much of the cross-border movement will surely continue to be (as it is today) short-term movement back-and-forth between the DPRK and China. Others leaving North Korea will seek short-term or long-term settlement in South Korea. But it is likely that a number of former “returnees” and others will seek to reach Japan, while some of those leaving the DPRK may find it difficult to settle in any of the immediately neighbouring regions, and may seek a new home further afield. So far, the region is very poorly prepared to deal with this migration. By way of conclusion, I shall suggest some steps which urgently need to be taken in the Japanese and regional contexts to prevent the outflow of migrants from North Korea from become a source of extreme human suffering, rising xenophobia and social conflict.

The other two steps relate specifically to Japan’s role in receiving North Korean emigrants. The information now available on the 1959-1984 repatriation makes it clear that the Japanese government, together with the North Korea government, has a deep moral responsibility to address the problems of those who migrated from Japan to the DPRK. The most obvious way to fulfill this responsibility is to make an explicit official commitment that Japan will accept all those former “returnees” and their immediate family who wish to resettle in Japan. This commitment should include provision of permanent residence rights to those who do not have Japanese citizenship, as well as measures to ensure that repatriate-refugees have access to government-supported welfare, language classes, skill-training and counseling services. All other North Korean refugees who arrive on Japan’s shores should have their claims for asylum assessed under the rules of the Geneva Convention.

Repatriation memorial, Niigata

In order to prevent this issue from becoming a source of fear and xenophobia, it is important that the Japanese government should prepare the ground for the acceptance of an inflow of repatriate refugees and other asylum-seekers from North Korea through reasoned public debate. The need for better understanding of the issue is highlighted by a recent case in which a Japanese repatriate-refugee was charged with violating immigration laws, after allegedly bringing to Japan people whom she falsely claimed were members of her family. The Japanese press, which had until then showed very little interest in the plight of repatriate-refugees, eagerly seized on this story of “people smuggling”, in some cases reporting it in lurid terms and with very scant regard for the privacy of individuals involved.[59]

A further essential step is for a wider range of Japanese and international NGOs to become involved in the process of supporting North Korean refugees (including repatriate-refugees) in Japan. At present, reliance on discretionary government decisions and on a small number of NGOs with distinctive politicized agendas leaves repatriate-refugees in an extraordinarily vulnerable position. The issue here is a delicate one. My aim is not to deny the value of the practical help that groups like the Mamorukai or the Japan Aid Association for North Korean Returnees provide to refugees. On the contrary, they are to be commended for giving vital assistance when others were not willing to do so. The problem is rather that other groups whose ideas are more firmly based on universalist human rights principles, rather than “human rights” nationalism, have failed to take up the issue. To put it simply, in the political environment of post-2002 Japan, issues related to the abductees and to North Korean refugees have come to be seen as part of the agenda of the “right”, and more liberal or left-leaning social movements have become reluctant to engage with them. The experience of the 1959-1984 repatriation reveals how dangerous it can be for those with few legal rights to be placed in a position of reliance on the humanitarianism of groups with strongly nationalist agendas. For this reason, it is particularly important for a wide range of civil society groups with diverse approaches and perspectives to become engaged with this issue, offering their expertise, skills and financial support to programs to support North Korean refugees in Japan.

Finally, the North Korean refugee issue has reached a point where isolated and uncoordinated national responses are increasingly inadequate. A regional approach is needed, with governments and NGOs should engage in informal consultation on practical and flexible responses to the needs of emigrants from North Korea. Although South Korea, China, Japan, as well as countries like Thailand, Laos and Mongolia (through which many North Korean refugees pass) are most obviously affected, there is also potentially a significant role to be played by other nations of the region like Australia and New Zealand, which have long been migrant-receiving countries. Wealthy nations with large immigration programs should be prepared to programs for accepting emigrants from North Korea who seek resettlement outside the Northeast Asian region. These programs should not simply be targeted at emigrants with high levels of technical skills, but should include a strong humanitarian component.

In a rapidly changing Northeast Asia, the movement of people across borders, and particularly emigration from North Korea, is likely to emerge as a major political and social challenge to national governments. But a new human rights based response to this problem – one that goes beyond the limits of “human rights” nationalism – could also become one element in the emerging regional collaboration which will link the countries of Northeast Asia (and more widely of East Asia and its southern neighbours Australia and New Zealand) as the Cold War in our region finally comes to end.

Tessa Morris-Suzuki is Professor of Japanese History, Convenor of the Division of Pacific and Asian History in the College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, and a Japan Focus associate. Her most recent book is Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War.

This is a revised version of a chapter that appeared in Sonia Ryang, ed., North Korea: Toward a Better Understanding. Lanham, Lexington Books, 2009.

Posted on March 29, 2009

Recommended citation: Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Refugees, Abductees, “Returnees”: Human Rights in Japan-North Korea Relations” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13-3-09, March 29, 2009.

NOTES

[1] Asahi Shinbun, 4 June 2007, p. 1; Yomiuri Shinbun (Tokyo), 3 June 2007, p. 1; Sankei Shinbun, 3 June 2007, p. 1.

[2] Asahi Shinbun, 4 June 2007, p. 1.

[3] Tokyo Shinbun, 17 June 2007, p. 3.

[4] Yomiuri Shinbun (Tokyo), 3 June 2007, p. 1

[5] Asahi Shinbun, 4 June 2007, p. 3.

[6] Sankei Shinbun, 30 June 2007, p. 17.

[7] Statement by Mr. Masayoshi Hamada, Vice Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan at the Preview of “Abduction: The Megumi Yokota Story”, 6 February 2007, see here, accessed 2 September 2007.

[8] See figures provided on the Chosakai website, accessed 2 September 2007.

[9] Chosakai Nyûsu, no. 511, 2 June 2007.

[10] For the sake of simplicity, I use the term “repatriate” in this article. However, it should be emphasised that vast those who migrated from Japan to North Korea in the Cold War years came from the southern rather than the northern half of Korea, and that for this reason the term “migration” or “resettlement” is probably more strictly accurate than the term “repatriation”.

[11] Chosakai Nyûsu, no. 511, 2 June 2007.

[12] Asahi Shinbun, 5 January 2007.

[13] Asahi Shinbun, 4 June 2007, p. 3.

[14] Mainichi Shinbun, 9 March 2009, p. 29.

[15] A similar estimate is put forward by a well-informed observer of the refugee issue, Ishimaru Jiro of Asia Press, who discounts predictions of hundreds of thousands of refugees, but says “it is possible that the numbers crossing the sea could be in the thousands”; Tokyo Shinbun, 22 July 2007, p. 29.

[16] Tokyo Shinbun, 22 July 2007, p. 28.

[17] See for example Tokyo Shinbun, 17 June 2007, p. 3.

[18] Site, accessed 2 September 2007.

[19] Uwe-Jens Heuer, “Human Rights Imperialism”, Monthly Review, vol. 49, no. 10, March 1998.

[20] See for example Vitit Muntabhorn, “Address of the UN Sepcial Rapportuer on the Situation of Human Rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK)”, Human Rights Council, March 2009, reproduced in the proceedings of the 9th International Conference on North Korean Human Rights and Refugees, Melbourne, Ausralia, 20-21 March 2009.

[21] Sato Katsumi, “Waga Tsûkon no Chosen Hanto”, Seiron, September 1995. As he explains in this article, Sato was expelled from the Japanese Communist Party in 1966.

[22] See Wada Haruki and Takasaki Soji, Kensho: Nitcho Kankei 60-Nenshi, Tokyo, Akashi Shoten, 2005, p. 71.

[23] Sato, “Waga Tsûkon”, op. cit.

[24] See, for example, Sankei Shinbun, 23 September 1992, p. 5; Mainichi Shinbun, 23 February 1992, p. 4.

[25] Wada and Takasaki op. cit., pp. 78-79.

[26] Sankei Shinbun, 11 August 1993, p. 4; Mainichi Shinbun, 23 February 1992, p. 4.

[27] See Ehime Shinbun, 18 April 1999, p. 8; on Park’s training in the academy, see Kim Hyung-A, Korea’s development under Park Chung Hee: Rapid Industrialization, 1961-1979, London and new York, RoutledgeCurzon, 2004, pp. 20-21.

[28] Sankei Shinbun, 13 July 1993, p. 24; rather surprisingly, Araki chose to run as not only as an independent, but also in the seat held by the highly popular Kan Naoto, where he was unsurprisingly defeated.

[29] See Araki’s homepage, accessed 3 September 2007.

[30] Chosakai Nyûsu, no. 507, 23 May 2007.

[31] Araki Kazuhiro, “Kita Chosen Sangatsu Shokuryo Kiki Setsu: Bohatsu ga Uchi ni Muku Baai, Soto ni Mukau”, Ekonomisuto, 30 January 1996, p. 72.

[32] See for example Chûnichi Shinbun, 12 February 1997, p. 11; Sankei Shinbun, 9 May 1997, p. 29; Hokkoku Toyama Shinbun, 29 January 1998, p. 32;

[33] The most plausible explanation put forward for the Terakoshi incident is that their fishing boat collided with a North Korean military or spy vessel engaged in secret maneuvers, and that they were rescued by North Korean forces, but not allowed to return to Japan for fear that they would report what they had witnessed.

[34] On the Terakoshi case, see Yomiuri Shinbun (Tokyo), 17 June 1987, p. 26; Mainichi Shinbun (Osaka), 16 October 2002, p. 1; Asahi Shinbun, 18 September 2003, p. 28; Hokkoku Shinbun, 19 September 2003, p. 46; Yomiuri Shinbun (Tokyo), 21 May 2005, p. 31

[35] See Richard Tanter, “Japan’s Indian Ocean Naval Deployment”, Znet, 26 March 2006.

[36] Sankei Shinbun, 13 February 1997.

[37] See, for example, Sankei Shinbun, 28 May 1999.

[38] Araki Kazuhiro, “Kita Chosen Hokai de Nihon no Futan, 14”, Ekonomisuto, 11 March 1997, p. 52.

[39] Araki Kazuhiro, “Nihonkai-gawa ni Nagaretsuku Kita Chosen Heishi no Shitai wa Sakana ni Shippai shita Hitotachi”, Ekonomisuto, 30 March 1999.

[40] Miura Kotaro, “Dappoku Kikokusha no Nihon Ukeire no tame ni”, Shokun, September 2006, pp. 92-101.

[41] It should be noted that Todd’s support for assimilation is argued specifically in the context of a French legal system which grants citizenship to all foreigners born on French soil, a situation very different from the that prevails in Japan.

[42] See, for example, Ma Seok-Hun, “Talbuk cheongsonyeon e daehan namhan sahwoi daeeung bangsik” in Jeong Byoeng-Ho ed. Welkeom tu Koria: Bukjoseon Saramdeul eui Namhan Sali, Seoul, Hanyang University Press, 2006.

[43] Miura Kotaro, “Dappokusha 4-nin no Nihon Tochaku”, June 2007, see here.

[44] Miura, “Dappoku Kikkokusha” op. cit., p. 101.

[45] Ibid., p. 101; On Ashizu, see Curtis Anderson Gayle, Marxist History and Postwar Japanese Nationalism, London and New York, RoutledgeCurzon, 2003, pp. 158-160.

[46] Sakanaka Hidenori, Nyûkan Senki, Tokyo, Kodansha, 2005, p. 139.

[47] Ibid., Ch. 10.

[48] See ibid., pp. 151-154; for an anaysis of Sakanaka’s ideas, see Song Ahn-Jong, “Korean-Japanese” Identity and Neoliberal Multiculturalism in Australia”, paper presented at the workshop Northeast Asia: Re-Imagining the Future, Australian National University, 4-6 July 2007.

[49] Sato, “Waga Tsûkon no Chosen Hanto”, op. cit.; see also Sato and Kojima, Seiron, 2003

[50] For example, Sankei Shinbun, 2 February 1959; “Jindo Mondai ni natta Hokusen Sokan”, Yomiuri Shinbun (evening edition), 5 February 1959.

[51] Sato, “Waga Tsûkon no Chosen Hanto”, op. cit.

[52] See Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea: Shadows from Japan’s Cold War, Lanham, Rowman and Littlefield, 2007.

[53] Ibid; see also Inoue Masutaro, Fundamental Conditions of Livelihood of Certain Koreans Residing in Japan, Japanese Red Cross Society, November 1956; copy held in the Archives of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC Archives), Geneva, B AG 232 105-002; letter from William Michel to ICRC, ”Mission Michel et de Weck”, 23 May 1956, p. 2, in ICRC Archives, B AG 232 105-002 ; Telegram from US Ambassador MacArthur to Secretary of State, Washington, 7 February 1959, in NARA, RG95, CFDF 1955-1959, box 2722, document no. 694.95B/759, parts 1 and 2.

[54] See Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea, op. cit., Ch. 14; see also “Record of Conversation with Comrade Kim Il-Sung, 14 and 15 July 1958”, in Dnevnik V. I Pelishenko, 23 July 1958, Foreign Policy Archives of the Russian Federation, archive 0102, collection 14, file 8, folder 95.

[55] Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea, op. cit., Ch. 16; see also “The Korean Minority in Japan and the Repatriation Problem”, report attached to confidential memo from Parsons to Herter, “Korean Repatriation Problem”, 10 July 1959, p. 3, DOS, FE Files Lot 61 D6 “Japan-ROK Repatriation Dispute”, reproduced as document no. 786 in microfiche supplement to Madeline Chi, Louis J. Smith and Robert J. McMahon eds., Foreign Relations of the United States 1958-1960 vols. XVII-XVIII; telegram from Ambassador Watt, Australian Embassy Tokyo, to Department of Foreign Affairs, Canberra, 15 July 1959, “Repatriation of Koreans”, in Australian national Archives, Canberra, series no. A1838/325, control symbol 3103/11/91 Part 1 “Japan – relations with North Korea”; Department of State Memorandum of Conversation, “Problems Relating to the Republic of Korea” 19 January 1960, reproduced as document no. 142, in Chi, Smith and McMahon op. cit. vol. XVIII, p. 275.

[56] Morris-Suzuki, Exodus to North Korea op. cit.

[57] See Jung Gunheon, “Nihon no Sekinin o Tou Hokuso Higaisha”, Chosun Online (Japanese Edition), 16 June 2005.

[58] See Abe Kohki, “Are You a Good Refugee or a Bad Refugee? Security Concerns and Dehumanization of Immigration Policies in Japan”, AsiaRights, issue 6, accessed 2 October 2007.

[59] See for example Asahi Shinbun, 11 March 2009, p. 27.