Formosa’s First Nations and the Japanese: from colonial rule to postcolonial resistance

By Scott Simon

Abstract: The Japanese administration of Formosa from 1895-1945 changed the island’s social landscape forever; not least by bringing the Austronesian First Nation people of eastern and central Taiwan under the administration of the modern nation-state for the first time. The Taroko tribe of Northeastern Taiwan (formerly part of the Atayal tribe) was the last tribe to submit to Japanese rule, but only after the violent subjugation of an anti-Japanese uprising in the 1930s. Shortly thereafter, however, Taroko men were recruited into the Japanese Imperial Army. The names of those who died during the war are now honored at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, a situation that occasionally becomes the object of protests by Taiwanese politicians. This article, based on field research in a Taroko community in Hualien, looks at how social memories of the Japanese administration have contributed to both Taroko identity and to various other forms of nationalism in contemporary Taiwan. How do Taroko individuals and collectivities remember the Japanese? How do these memories articulate with nationalist ideologies in the larger Taiwanese society?

On June 13, 2005, Taiwanese independent legislator May Chin, who claims an Atayal identity, arrived in Tokyo with a group of fifty comrades-in-arms representing nine indigenous tribes from Taiwan. Their goal was to protest in front of the controversial Yasukuni Shrine where the spirits of 2.5 million war dead are honored. Among the dead commemorated in the shrine are 28,000 Taiwanese, including approximately 10,000 aboriginal men, who fought for the Japanese Imperial Army during the Pacific War. Although the families of Taiwanese soldiers have long demanded compensation from Japan for unpaid pensions, this protest made only one demand: that the names of aboriginal soldiers be removed from the shrine.

When May Chin and her cohort arrived at the shrine on June 14, Japanese police refused to let them get off the bus, allegedly in order to protect them from Japanese right-wing extremists who had already arrived at the scene. For a few days, this became the leading news item in Taiwan, with television news broadcasting images of Taiwanese aborigines in traditional dress being prevented from exiting their bus by Japanese police. May Chin accused Japan of violating their democratic rights of protest. This event, part of the tensions between Japan and its neighbors, underscores the importance of memories of Japanese occupation to contemporary indigenous peoples in Taiwan.

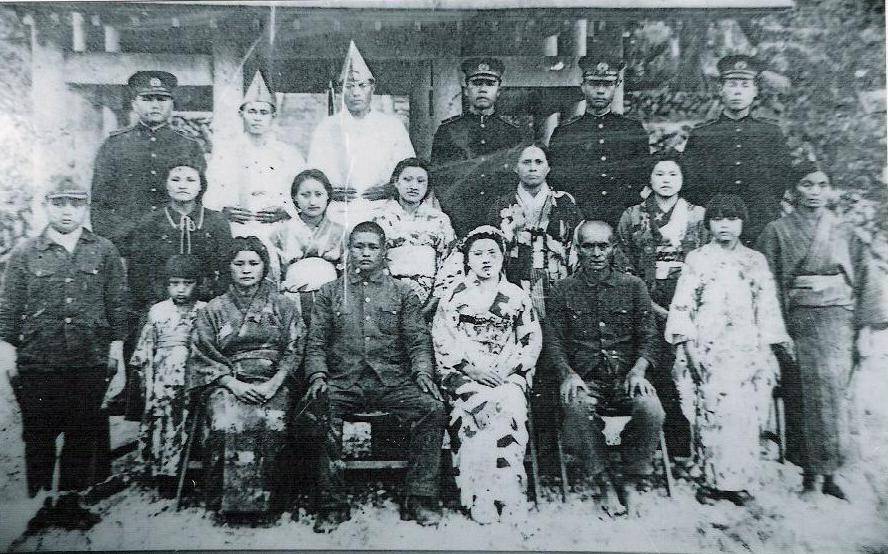

May Chin

Chin’s aboriginal protest occurred at a time of widespread protest against Japan that involves more than Formosan aboriginal grievance against the former colonial overlords. During the same summer, the Chinese and South Korean governments also objected publicly to both Japanese Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s visits to the shrine and revisions to history textbooks in Japan. During the race for Taiwan’s KMT (Chinese Nationalist Party) leadership, candidate Wang Chin-ping also led protests against Japanese occupation of the Senkaku (Tiao-yu-tai) Islands which Taiwan claims is a part of the Republic of China. May Chin’s protests at the Yasukuni Shrine thus articulate with a larger pan-Asian mobilization against Koizumi. The memories of the deceased aboriginal soldiers, depicted as victims of Japanese imperialism by Chin and her group in much of the Taiwanese media, are potent symbols when mobilized in that struggle. As this essay attempts to illustrate, however, Taiwanese memories of Japanese colonialism are very different from Chinese and Korean memories. Korean and Chinese anger toward the Japanese has been much more potent than that of the Taiwanese, many of whom also remember positive dimensions of their experience under Japanese colonial rule. It is thus crucial to contextualize the local meaning of anti-Japanese protest and to grasp how memories of the Japanese occupation are mobilized to different ends in different situations.

Scholars working on collective memory, following in the footsteps of Maurice Halbwachs (1980 [1950]) and Henri Lefebvre (1991 [1974]), point out that social space is the product of struggle between conflicting groups of people attempting to give concrete form to collective memory. Through her protests at the Yasukuni Shrine over several years, May Chin brought Japan’s Formosan aboriginal soldiers into Taiwanese social memory as symbols of Taiwanese, and particularly aboriginal, suffering and injustice during the colonial period. In understanding these and other political events, the job of the anthropologist is to look beyond media images and political symbolism, elucidating and understanding social memory within a broader ethnographic and political economic context (Gupta and Ferguson 1997).

Like most issues in Taiwan, memories of Japanese administration must be understood as part of the contending nationalisms of “pan-blue” and “pan-green” political discourse which shape the national political agenda. The Chinese Nationalist “pan-blue” parties include the KMT, the People First Party (PFP), and the Chinese New Party (NP). In favor of eventual unification with China, at least under the conditions that China democratizes and becomes prosperous, they emphasize the importance of unity among ethnic groups and highlight memories of cross-ethnic resistance against Japan. The Taiwanese nationalist “pan-green” parties include the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU). Stressing Taiwanese autonomy from China, they emphasize Taiwanese differences from mainland Chinese. They thus celebrate aboriginality as a non-Chinese identity; and perceive both Japanese and Chinese rule as colonialism at the expense of all Taiwanese. One important element of pan-green discourse is that the Japanese brought modernity to the island, making its Taiwanese inhabitants more civilized and advanced than the Chinese who arrived with Chiang Kai-shek in 1945 and afterwards. These two ideologies color different spots on the maps of these contested “imagined communities” (Anderson 1983) on the island.

May Chin’s aboriginal protest at the Yasukuni Shrine was part of this larger struggle between pan-blue and pan-green camps. Just two months earlier, Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU) Chairman Shu Chin-chiang had paid a visit to the shrine and was greeted upon his return to Taipei by May Chin and a group of protesters who pelted him with eggs at the airport. Two days later, a coalition of veterans who had served in the Japanese military protested outside of Taiwan’s legislature in favor of Shu’s visit to the Shrine and against May Chin’s actions. Chen Chun-chin, president of the Association for the Bereaved of Taiwanese Serving as Japanese Soldiers, defended Shu and others of his generation who regularly visit the Yasukuni Shrine to pay respect to their former colleagues and relatives. He said that the KMT has consistently neglected former Japanese soldiers, as they failed to bring many survivors back from Japan after the war and subsequently failed to seek compensation from Japan on their behalf. The TSU thus promised to seek compensation for the veterans and build a Shinto Shrine in Taiwan for the memory of those who died in the war.

May Chin began organizing her trip immediately after this conflict, making the Yasukuni Shrine into an aboriginal issue. Without anthropological study of the memory of Japanese colonialism, however, it is difficult to understand the extent to which May Chin and other politicians represent the grievances of indigenous communities or merely use aboriginality in the service of other political goals. Based on fieldwork in Taroko communities, we query the relationship between the mobilization of social memory in such protests and aboriginal perceptions of the Japanese period. How and why are memories of the Japanese period contested in their communities? What is at stake for these people? What other social memories exist, and what alternative political possibilities do they suggest?

Memories of Japan: Voices from the Field

In the summer of 2005, I spent three months doing field research in a Taroko village which I will call Bsngan. I had previously established an ongoing relationship with the village, having visited it several times since 1996 and having worked with members of the community on issues surrounding the Asia Cement excavation on land belonging to villagers. The village lies at the foot of the Taroko National Park and has a frequently contentious relationship with park administration. This village is inhabited largely by members of the Truku subgroup of the Taroko tribe, which is composed also of the Tkedaya and Teuda subgroups.

The Taroko are related to the Atayal tribe of which May Chin is a member, being born of an Atayal mother and Mainlander father. The Taroko broke away from the Atayal tribe, however, on January 14, 2005, when Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan recognized their long-standing claims to be an independent ethnic group. Many observers, including some members of the tribe, argued that this reclassification was divisive and reduced the numbers of the tribe, hence political influence. Taroko claims to be different from the Atayal, based on linguistic and cultural criteria, nonetheless, are recorded in Japanese-era ethnographic studies (Taiwan Governor-General Provisional Committee 1996: 5). The reclassification gave the Taroko greater autonomy and positioned them to perhaps become the masters of Taiwan’s first indigenous autonomous region. As discussed below, the establishment of a Taroko autonomous region is currently promoted by the Presbyterian Church, an institution with strong historical links to the pan-green parties in Taiwan. In Bsngan, the Presbyterian Church has its roots in the Japanese period, when the local authorities tried to suppress all forms of Christianity and the local people were forced to hold services clandestinely in a cave.

As in most Taiwanese indigenous villages, the people of Bsngan have vivid memories of the Japanese occupation that ended with the conclusion of World War II. This village of 2,224 people, with its main residential area located at the mouth of the Taroko Gorge, was important as the site of armed resistance against the Japanese. Even before the tribe was subdued, it was a trading post where aborigines could sell hides to Japanese and Hoklo-speaking Han Chinese (now the “Native Taiwanese”) in exchange for such items as alcohol, matches, and salt. Like most communities in Taiwan, the village is dotted with Japanese-era construction. In Bsngan, those architectural reminders include a Japanese-era power plant, an abandoned campus of workers’ dormitories, a few homes, and the former nursing station.

The Japanese language can still be heard every day in Bsngan, not just in the conversations of the elderly, but also in songs crooned in road-side karaoke stalls and in everyday Taroko conversation. Even young people use “arigatoo” to say thank you, some shopkeepers are in the habit of calculating money in Japanese, and the Taroko language is interspersed with Japanese words. Church sermons, for example, are delivered in Taroko peppered with Japanese words in both the Presbyterian and True Jesus churches. These are not just foreign church-related terms like kyokai (church), and kamisama (gods), but also such words as jikan (time), ishoo ni (together), and tokubetsu (especially). The use of Japanese time measurements, including the days of the week and even usages such as nansai da to ask a person’s age or nanji da to inquire about the time, all reveal how modern usages of time were introduced by the Japanese. The young as well as the old incorporate Japanese into daily conversation.

Memories of the Japanese era come up in daily conversation, and not just by people who lived through that era, showing that the Japanese experience is central to Taroko identity. In contrast to the historical memories promoted by politicians such as May Chin, who cast themselves in a Manichean drama of good versus evil, memories of Japan in the villages are far more nuanced. This paper draws its examples primarily from conversations with members of the Mawna family. [This, like all names of private individuals, is a pseudonym.] The courtyard of Ukan Mawna, decorated with photos from the Japanese era, is often the site of dinners and conversation over tea between leading members of the community. Along with the courtyard and exhibition hall of his brother, who has done research on the tribe’s custom of facial tattooing, this is also one of the first places that a visitor to the village will see. The memories of this family are highlighted here not only because they can be said to be representative of the tribe, but also because they illustrate the complex articulation between personal and social memory.

The Japanese as Agents of Modernity

Like the entire Taroko tribe, the family of Ukan Mawna has had a close relationship with Japan. Their mother, whose biological mother had traveled around the island making facial tattoos for members of the Atayal tribe, spent most of her childhood in the home of a Japanese policeman. After the Japanese sent her to nursing school, she worked in the clinic in the village. Her children boast that she vaccinated the entire village. With her medical training, in fact, she was one of the main agents of Japanese modernity and a key part of the process of displacing traditional Taroko healers from their position in society. In the past, each village had healers, who could contact the spirit world and prescribe cures for medical and other ailments. Now Bsngan has no healer. The nearest healer is an elderly woman in a neighboring village. [1]

Ukan’s father had a much more conflictual relationship with the Japanese, especially with the police. One of the earliest aboriginal converts to the True Jesus Church, which was illegal under Japanese occupation, he established the congregation in Bsngan. In the many social gatherings at his home, Ukan Mawna delights in telling the miraculous story of his father. At one point, the Japanese arrested him, put him on trial, and planned to execute him for his illegal missionary activities. They imprisoned him in a bamboo hut to await execution. On the night before his execution, however, a typhoon struck the island and destroyed his bamboo prison. He managed to escape through the forest and his sentence was later commuted. Ukan concludes his story by saying that his father subsequently received a Japanese education and learned to love the Japanese in the village. “My father never let anyone say a bad word about the Japanese,” he says with every re-telling of the story.

Ukan, a retired policeman, participates regularly in meetings to discuss development plans in the village. He is an outspoken proponent of restoring Japanese-era buildings as tourist sites, and has even suggested rebuilding the Shinto Shrine as a tourist site and historical museum. On one of many drives through the countryside in which he pointed out Japanese-built irrigation systems, water towers, power plants and an alcohol distillery, he summed up his perception of Japan’s legacy in the village:

“There are no Taroko who hate the Japanese. Quite the contrary. They love the Japanese. Why do they love the Japanese? Because of the charity of the Japanese. The Japanese took them from the worst kind of feudalism and brought them civilization. It was the Japanese who brought them roads and electrical power plants.”

Neither Ukan nor most members of his tribe are apologists for Japanese colonial expansion. In contrast to pan-green revisionists, they do not use nostalgic memories of Japan to criticize the KMT. Ukan, in fact, is a staunch supporter of the KMT in his village, is an acquaintance of May Chin, and has even made a TV series on the 1930 Wushe Incident, in which violent conflict rose between the Japanese and the Taroko. In that series, he portrayed the Japanese as cruel overlords who manipulated differences between the Truku, Tkedaya and Teuda to gain control of their territory, even using some groups in military attacks against the others. These and other memories of Japanese rule, also a part of village life, emphasize the pain of colonial rule. Unlike the social memories mobilized by politicians, however, individual memories such as those of his parents are often contradictory, highlighting the brutality of the Japanese but also their contributions to the community.

Memories of Japan: the Price of Development

Older women remember vividly one of the most painful episodes of the colonial era, as it was the Japanese who banned the Atayal and Taroko custom of tattooing their faces. Whereas facial tattoos were formerly considered a sign of female beauty and were necessary conditions for marriage, the Japanese quickly brought an end to the custom. Older women recall that they had to have their facial tattoos removed in order to attend school, which they and their families wanted because Japanese education held out the promise of a better life. [2] The girls thus removed their tattoos by having the skin removed surgically, which sometimes disfigured their faces permanently. One graduate student at Donghwa University told me that she had interviewed several of these women, one of whom burst into tears at the memory of the painful and humiliating operation as well as subsequent disfigurement.

Taroko men identify strongly with the forest, so closely associated with their lifestyle of hunting and gathering. They recall how they once lived in villages high in the mountains, but were forced by the Japanese and later by the KMT state to move down into the plains. The Taroko still lament the fact that this forced relocation removed them from their ancestral lands and made it more difficult to access their traditional hunting territories. The move also incorporated them into a new social system that included agriculture and the use of cash rather than commodity exchange in trade relations. Many claim that they were better off with a lifestyle of hunting and gathering than they are today, when most men make a living as construction or cement workers if they have regular employment. Those who venture into the forests to hunt in the nearby National Park that covers their traditional hunting territories risk being arrested as poachers.

Frequently, however, the men contrast Japanese rule with subsequent Chinese rule under the KMT, adding subtle nuance to negative colonial memories by contrasting that experience with what came afterwards. Ukan Mawna, for example, said that the Japanese left the former village intact and they often visited it after moving to the plains. The roads to the village were maintained and the Japanese constructed a Shinto shrine there. Another elder pointed out that the Japanese cut down camphor and other trees, but they always negotiated with the indigenous peoples about access to land. They also took good care of the aboriginal people with education and health care, even sending the sick to be treated at Taiwan Imperial University hospital if necessary. This theme of the Japanese era as the “good old days” is not uncommon in Taroko reminiscences of the era, even as the same interlocutors also acknowledge the pain of colonial occupation.

Japanese and Ayatal in Taroko

Memories and Identity: Comparing Indigenous and Native Taiwanese Experiences

These indigenous memories of Japanese occupation articulate with, but remain distinct from, those of the so-called “Native Taiwanese.” They are thus not merely the result of the Native Taiwanese taking over the construction of political discourse under the presidencies of Lee Teng-hui and Chen Shui-bian. The Native Taiwanese are the Hoklo and Hakka groups whose ancestors arrived in Taiwan from Fujian and Guangdong Provinces between the 17th and 19th centuries. Unlike the Mainlanders, who arrived after World War II with Chiang Kai-shek, the Native Taiwanese lived through Japanese occupation. For many Native Taiwanese, memories of the Japanese occupation are central to their ethnic identity. For them, Japan is primarily a symbol of modernity and their Japanese education a sign of their higher levels of development compared to Mainlanders (see Simon 2003). For aboriginal people, however, the Japanese period was also important to identity formation because it positioned them as resisters against colonial encroachment. This makes their memories of Japan very different from those of the Native Taiwanese. Whereas Native Taiwanese collective memory focuses on the trope of modernity, the Taroko use memory to highlight their fierce resistance to outsiders.

In Bsngan, even young people take pride in what they describe as the “fierceness” of their tribe. One young woman, whom I shall call Biyuq here, explained to me over coffee in her shop how her tribe had resisted the Japanese for decades. The Japanese built many roads up into the mountains, she explained, in order to transport heavy artillery up to high places and shoot down on the local people. It was very hard for the Japanese to take over Taroko territory, however, because the hunters would hide in the forest and then attack the Japanese with bows and arrows.

By far the best-known event in Taiwan is the Wushe Incident of 1930, the memory of which has often been mobilized by pan-blue parties as evidence of “Chinese” resistance to Japanese occupation. On October 27, 1930, a group of over 300 Atayal warriors led by Mona Rudao attacked Japanese spectators at a sports event in Wushe and killed 130 people. It took Japanese forces two months, and the deaths of 216 aboriginal people, to completely quell the uprisings that followed (Ukan 2002). In an account that emphasized Taroko rather than Chinese identity, Biyuq explained that the Wushe Incident was meant to be the final battle, and that one village decided to sacrifice themselves for the good of the tribe as a whole. According to her version of events, all of the women and children committed suicide to encourage the men to sacrifice their lives willingly. [3] The men then went out to fight the Japanese to the death. Without families to return to, they had no need to fear death and could fight to the end to drive the Japanese out of the forests forever.

Although the ultimate result was military defeat, mass slaughter and loss of territory, the Taroko still remember this event as a tribute to their tribal fierceness. They are not mistaken. According to John Bodley 4,341 Japanese and Han Chinese settlers died at the hands of indigenous Formosans between 1896 and 1909 (Bodley 1999: 56); and a further 10,000 casualties were recorded during the 1914 pacification campaigns against the Taroko (Nettleship 1971: 40). [4] This experience of resistance, which is constantly revived and celebrated through collective memory, altered Taroko life forever. Although the suppression of the Tribe in the Taroko, Hsincheng and Wushi Incidents eventually ended control over their own territory, it also made the Taroko self-conscious subjects of history. This has been translated from personal to social memory in the Taroko Gorge. It remains, however, a social memory very different from that promoted by May Chin in Tokyo.

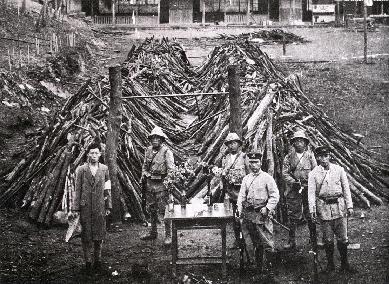

Funeral pyre at the Wushe Elementary School

Museum Identity: Social Memory of the Taroko Incident

In the summer of 2005, the Taroko tribe became the subject of a special exhibit in the basement of the Taroko National Park Visitors Centre. This exhibit, designed by temporary curator Chin Shang-teh (a Han from Tainan and a graduate student at National Donghwa University in Hualien), illustrated the history of the Taroko Incident with photos and artifacts he had collected in Japan. The exhibit showed how the Japanese slowly encircled indigenous villages, even constructing electric fences to restrict their movement, in order to get them to surrender to Japanese forces.

In 1910, the Japanese Governor-General Sakuma Samata launched the “Five Year Plan to Subdue the Barbarians.” In May 1914, Japanese troops attacked the people of the Taroko Gorge by coming in simultaneously from Hualien City in the South and Wushe through mountain passes from the West. The Taroko resisted fiercely for 74 days, but were ultimately forced to surrender control of their lands to the Japanese.

The exhibit contained graphic photos of the military expeditions, including the electric fences, Japanese artillery, and Taroko people resisting with simple hunting guns. Many of the photos were taken from memorabilia albums sold in Japan at the time to celebrate the victory. The final panel of the exhibit, a drawing of the sun setting over the mountains, brought the issue of resistance to contemporary Taiwan. The text said that the Taroko came down from the mountains, saw their land occupied by outsiders, and “have not yet been able to return to their ancestral lands.” Putting it into context, museum visitors could recognize that the arrival of the Republic of China and later the establishment of the Taroko National Park were precisely extensions of imperial conquest, the replacement of one colonial overlord with another. This written discourse repeated Taroko activist Tera Yudaw’s contention that the Taroko National Park is a form of “environmental colonialism” (Tera 2003: 169).

Return our land

According to the curator, the exhibit almost never saw the light of day. When the Han park superintendent viewed the exhibit the day before the opening ceremony, she asked the curator to remove the final panel with its oblique reference to the National Park as another colonial power. She said that it risked inciting “ethnic conflict.” The curator refused to comply and threatened to remove the entire exhibit if she removed the plaque without his permission. The superintendent backed down and allowed the exhibit to open with the final panel in place.

In the subsequent months, however, the National Park refrained from advertising the exhibit to the surrounding communities. Instead, the Presbyterian Church, which has close links with the indigenous social movements, took the lead in inviting their members to visit the exhibit. This move was consistent with other church actions in promoting Taroko identity. The Presbyterian Church, in fact, has become the main institution behind the recognition of the tribe as distinct from the Atayal, and now the most important lobbyist for the establishment of autonomous indigenous regions in Taiwan. [5] The Presbyterian Church is well-known for its close relationship with both the DPP (Rubinstein 1991, 2001) and indigenous social movements (Stainton 1995, 2002). They hope that local recognition of indigenous sovereignty will eventually lead to international recognition of Taiwanese sovereignty.

The difficulties encountered by the curator of this exhibit and its promotion by the Presbyterian Church rather than by the park administration and the local government reveal the political fault lines underneath these contested social memories. The main difference centers on indigenous autonomy, an issue that divides the pan-blue camp and the pan-green camp in indigenous communities and beyond. The DPP has promised to establish autonomous districts for indigenous peoples as part of its desire to emphasize the non-Chinese identity of the island. Its policy assumes that self-determination should be the basis for activities in indigenous areas just as they insist on the right of self-determination for Taiwan. The pan-blue parties favor more assimilationist policies toward indigenous peoples, emphasizing economic development and employment over autonomy. Their parties thus say little about self-government and justify the employment-generating activities of mining and other companies on indigenous land. Just as the memories of Japan evoked by May Chin fit into a larger pan-blue imagining of Taiwan, the memories exhibited in the park exhibition fit into a wider pan-green discourse. In this context, ownership of indigenous social memory has potential implications that go far beyond the local community.

Conclusion

Anthropologists John and Jean Comaroff have called for bringing historical understanding into ethnography, saying that, “No ethnography can ever hope to penetrate beyond the surface planes of everyday life, to plumb its invisible forms, unless it is informed by the historical imagination (1992: xi). ” It is important to note, however, that the historical imagination is often also a national imagination; part of contested ideologies that can very well influence the fate of a people. Yet every time historical memory is mobilized in support of contemporary nationalist narratives, conflicting personal memories are silenced. This dynamic is especially visible in Taiwan, a society torn between two conflicting historical imaginations.

May Chin, in attacking the former colonial overlords, has long used highly publicized protests to draw indigenous support away from the pan-green parties. In this case, she managed successfully to draw attention away from pan-green TSU attempts to seek compensation for the veterans and even to portray that party as complicit with Japanese imperialism. In doing so, she discredited locally the same people who promise indigenous autonomy within the framework of the existing state on Taiwan. She is able to do so at relatively low cost by mobilizing resentment against Japan, which also articulates well with the larger geopolitical context in which both China and Korea protest against state visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, preeminent symbol of Japanese wartime nationalism and empire.

In the months leading up to the local elections in December, 2005, the KMT continued to appropriate indigenous social memory by covering their headquarters in Taipei with a large image of Wushe hero Mona Rudao. This tactic has the twin effect of appealing to Mainlander anti-Japanese sentiments and of positioning the KMT as the voice of indigenous peoples. The party’s consistent support in indigenous areas, including overwhelming support in the December 2005 local elections, suggests that this strategy has contributed to electoral success. May Chin’s protests are only a part of this larger struggle.

Mona Rudao center

Taroko perceptions of May Chin, however, are just as ambivalent as are their memories of Japan. In fact, although most aboriginal people support the pan-blue KMT and PFP parties (Wang 2004: 695) and although May Chin was re-elected, there was very little enthusiasm in Bsngan for her well-publicized protest trip to Japan. As the news came on TV the morning after her trip, I asked the people around me in the breakfast shop (an important place for anthropological research) what they thought of the commemoration of aboriginal soldiers in the Yasukuni Shrine. One middle-aged man and Presbyterian Elder stated matter-of-factly that the news has nothing to do with him, since the protesters are not Taroko. He added that May Chin has spent so much time with Mainlanders that she no longer understands aboriginal needs.

When I asked if any Taroko had served in the Japanese military, he said that they had. He insisted, however, that many groups are commemorated in the Yasukuni Shrine, so it would be unreasonable for any one group to ask for their spirit tablets without returning them to the countries and families of all 2.5 million spirits. The breakfast shop owner, who is a member of both the Presbyterian church and the KMT intervened by saying that the Taiwanese who fought for the Japanese were not volunteers. The conversation turned into a discussion of reasons why they would serve, the man saying they were forced to join the army by circumstances of poverty, not by Japanese conscription. Despite different interpretations of the Japanese period, however, one perception emerged as consensus: that May Chin was acting primarily for personal political gain, trying to position herself as the primary advocate of indigenous communities even in comparison to other aboriginal KMT candidates. If it were not for her political manipulations, which included getting funding for the trip, it is unlikely that her group of aboriginal people would show up to protest at the shrine.

Personal memories of the Japanese era in the Taroko community are thus ambivalent, showing both positive and negative aspects of the occupation. As Halbwachs observed, historical memory is preserved not just in regions, provinces, parties, and classes, but also in certain families and in the minds of individuals. It is thus important to make a distinction between individual and collective memory (Halbwachs 1980: 51). The individual memories of Japanese colonialism are now passing away with the individuals who carry them. The few remaining Taroko men who served in the Japanese military show no resentment against the Japanese; if anything, they were well treated (Nettleship 1971: 43). It is striking, in fact, that few Taroko individuals even bring up the issue of having been forced into the Japanese military, focusing instead on issues of forest resources, education, health, and tattooing. This gap, more than anything, illustrates how those specific memories are mobilized by politicians more than they are discussed by individuals.

Collective memories persist, given expression through monuments, actions in space including demonstrations, as well as words spoken in the community; they often reflect current political struggles and can be mobilized for political goals. Since May Chin’s protests at the Yasukuni Shrine are so obviously tied to pan-blue politics, there are good reasons for the Taroko to remain ambivalent about those events. They know that the discourse comes from outside of their community and is tied to a political agenda not of their own making. The social movement for autonomy is also led by Taroko community members, including Presbyterian ministers and school teachers. In spite of pan-blue success in the elections, they provide a very prominent alternative to the historical imagination of the KMT and its allies; albeit one that is also widely perceived as coming from outside of the local community. The struggle for indigenous memory is in many ways a struggle for indigenous future as local members of different parties claim to be the legitimate heirs of Taroko fierceness. Like any claims for a valuable inheritance, they are hotly contested. The ultimate outcome, especially whether or not they will choose a pan-green version of local autonomy, is thus far from certain.

In any event, it is clear that the Japanese occupation of Taiwan was the defining moment that constituted aboriginality as it is currently imagined in Taroko territory. Before the Japanese arrived, the Qing Dynasty had merely labeled the Taroko and other unassimilated tribes as “raw barbarians” (shengfan) and had not attempted to administer their territories. The threat of having their heads cut off, in fact, was sufficient deterrence to keep Chinese settlers out of indigenous territories — especially in Taroko land. The Taroko tribe was known as “wild people” and was only “civilized” after the Japanese came to Taiwan (Nettleship 1971: 39). When they finally encroached on those territories with far superior weaponry, however, the Japanese also created the conditions for resistance that became the core of Taroko identity for members of all sub-groups.

As aboriginal individuals subsequently became agents of Japanese modernity, even as soldiers for the Japanese army, they were conscious of doing it as members of the fierce Taroko tribe. It was thus the Japanese occupation that fashioned the Taroko into self-conscious historical actors. The various social movements of this tribe in recent years, with demands for name changes, land settlements, and now autonomy, show that this spirit of resistance is alive and well. As “savages” become soldiers, and soldiers become social activists, the tribe has rapidly developed a First Nations identity as advocates of both stripes mobilize memories of past resistance in different contexts. Whether the state is green or blue, therefore, Taroko memories will continue to shape the relationship between state and tribe.

Scott Simon has conducted ethnological research in Taiwan since 1996. He is Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Ottowa. He is author of Sweet and Sour: Life Worlds of Taipei Women Entrepreneurs and Tanners of Taiwan: Life Strategies and National Culture. This research is generously funded by a grant from the Canadian Social Science and Humanities Research Council. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on January 4, 2006. Thanks to Mark Selden and Jim Orr for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.

References:

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso Press.

Barclay, Paul. 2003. “Gaining Trust and Friendship’ in Aborigine Country: Diplomacy, Drinking, and Debauchery on Japan’s Southern Frontier.” Social Science Japan Journal 6 (1):77-96.

Bodley, John. 1999. Victims of Progress. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

Comaroff, John and Jean. 1992. Ethnography and the Historical Imagination. Boulder: Westview Press.

Gupta, Akhil and James Ferguson. 1997. Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology. Durham: Duke University Press.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1980 (1950). The Collective Memory, translated by Francis Ditter and Vida Yazdi Ditter. New York: Harper and Row.

Honda, Katsuichi. 2000. Harukor: an Ainu Woman’s Tale (translated by Kyoko Selden). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Huang, Shiun-wey. 2004. “ ‘Times’ and Images of Others in an Amis Village, Taiwan.” Time & Society 13 (2&3): 321-337.

Kayano, Shigeru. 1994. Our Land was a Forest: an Ainu Memoir (translated by Kyoko Selden). Boulder: Westview Press.

Lefebvre, Henri. 1991 (1974). The Production of Space, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Nettleship, Martin A. 1971. An Experiment in Applied Anthropology among the Atayal of Taiwan. Ph.D. thesis in Anthropology, London School of Economics.

Rubinstein, Murray. 1991. The Protestant Community on Modern Taiwan: Mission, Seminary and Church. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

_____. 2001. “The Presbyterian Church in the Formation of Taiwan’s Democratic Society, 1945-2001.” American Asian Review 19 (4): 63-96.

Simon, Scott. 2003. “Contesting Formosa: Tragic Remembrance, Urban Space, and National Identity in Taipak.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 10 (1): 109-131.

Stainton, Michael. 1995. Return our Land: Counterhegemonic Presbyterian Aboriginality in Taiwan. M.A. thesis in Social Anthropology, York University, Toronto.

_____. 2002. ‘Presbyterians and the Aboriginal Revitalization Movement in Taiwan.’ Cultural Survival Quarterly 26 (2): 63-65.

Taiwan Governor-General Provisional Committee on the Investigation of Taiwanese Old Customs. 1996. Report on the Old Customs of Barbarian Tribes, Volume 1, Atayal Tribe, translated by Academia Sinica Institute of Ethnology Translation Group. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Tera Yudaw. 2003. Muda Hakaw Utux (Crossing the Ancestor’s Bridge). Hualien: Tailugezu Wenhua Gongzuofang.

Ukan, Walis. 2002. “The Wushe Incident Viewed from Sediq Traditional Religion: a Sediq Perspective” Pp. 271-304 in From Compromise to Self-Rule: Rebuilding the History of Taiwan’s Indigenous Peoples, ed. by Shih C.F., Hsu S.C. and B. Tali. Taipei: Avanguard Publishing Company.

Wang, Fu-chang. 2004. “Why did the DPP Win Taiwan’s 2004 Presidential Election? An Ethnic Politics Interpretation.” Pacific Affairs 77 (4): 691-696.

Endnotes

[1] After a long period in which these practices had fallen out of favor and were perceived as sinful, there are signs of a revival. She now has two apprentices. That, however, is beyond the scope of this essay.

[2] For similar accounts about how the Ainu of Hokkaido were forced to end tattooing practices and join Japanese modernity in colonial Hokkaido, see Honda 2000 and Kayano 1994.

[3] I have not seen this account of the Incident in historical accounts of the event, but that does not mean she is mistaken. It is interesting how her story makes the women critical agents of Taroko history.

[4] Unfortunately, neither of these authors could break down the statistics into different national and ethnic groups of the victims.

[5] To outsiders, it may seem unclear why they would support Taroko independence from the Atayal. From the perspective of the activists, however, it is a logical strategy. Considering that indigenous communities get many financial resources from county governments and that political factions are closely tied to county electoral processes, it will be much easier for them to develop the necessary consensus within the smaller Taroko tribe rather than within a larger Atayal tribe spread throughout several counties and one urban area in northern Taiwan. Even then, it is likely that the Taroko Autonomous Indigenous Region will only include the Taroko of Hualien because those in Nantou do not support the project. Members of pan-blue factions accuse the DPP and their Presbyterian allies of manipulating the Taroko in order to gain an electoral foothold in Hualien County.