|

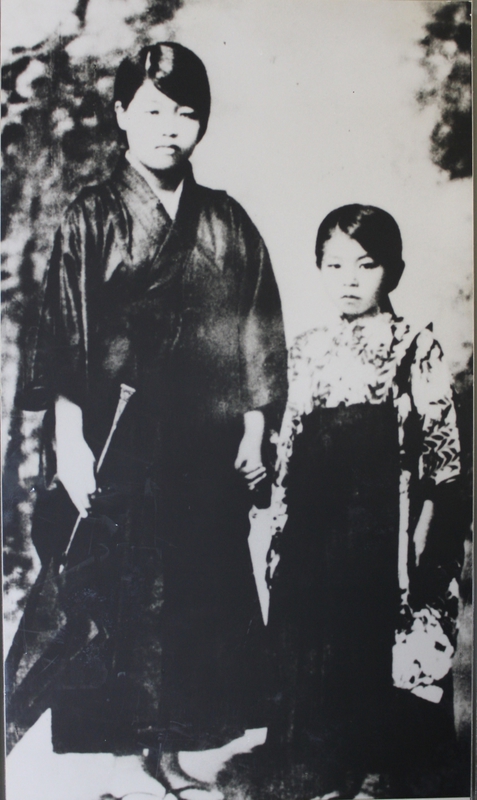

Ishikawa Takuboku and Horiai Setsuko after their engagement in 1904. Courtesy of the Ishikawa Takuboku Memorial Museum. |

The society of Ishikawa Takuboku’s era was in dramatic political flux, and its complex issues became his personal obsessions. After his death, Takuboku’s preoccupations came to be seen as a symbol of the social and emotional upheavals of his times.

The key word in the last two decades of the Meiji era (1868-1912) was “polemics.” Intellectuals and socially conscious people were actively involved in a nationwide discourse, played out in all aspects of the culture—literature, theater, graphic arts, journalism—as to what the nature of future Japanese society should be. In essence it is the same current that continues to rage today: Should society be open to ideas on the basis of their true merit, creating a fluid situation that leads to the betterment of all classes? Or should the body polity be unified in thought and action behind one ethnic, religious or ideological idea, an idea that purportedly makes the nation “stronger” and more successful at engaging in conflicts with other countries?

It is clear that Takuboku identified in his writing with those people who wanted fervently to liberalize Japanese society; and this at a time when the nation was on a mission to create an empire in its expanding hemisphere of influence.

Takuboku wrote about the downtrodden because he saw himself as one of them. Life for him, with a wife, daughter and mother to support, was a struggle for bare survival. The lack of job security that plagued Takuboku’s life, the necessity to move from place to place wherever there was work to be had, the anxiety caused by the fact that a person could be shunned for arguing against injustice, the introduction of restrictions on freedoms, the burgeoning oppression of people seen by the government as “radical” … these aspects of Takuboku’s times have once again become all too familiar in today’s Japan. This is reason enough to consider him our contemporary.

He is best remembered for his tanka. The tanka is one of Japan’s oldest native forms of poetic expression. Tanka—literally “short poems”—contain 31 syllables. The genre dates back to the 8th century anthology “Manyoshu,” and was refined in the “Kokinshu,” the primary anthology of the Heian period (794-1185).

One of Takuboku’s most famous tanka is “Labor” (I have given these short poems titles to sharpen their focus in translation). Here we see the struggle and the toll it takes on his psyche.

However long I work

Life remains a trial.

I just stare into my palms.

Another is “Revolution” …

Nothing seems to disconcert my wife and friends

More than my going on about revolution

Even when struck down by illness.

Two crucial historical events occurring in Takuboku’s lifetime deeply affected him. The first is the attempt by activist Tanaka Shozo to hand a petition to Emperor Meiji to halt the toxic waste produced by the Ashio Copper Mine in Tochigi Prefecture that was polluting the waters at farms downstream. Though Takuboku was only 15 at the time of this incident (December 1901), it impacted deeply on his consciousness.

Tanaka Shozo was one of the world’s first ecological pioneers. Not only an amazing social thinker who formulated the 「根本的河川法」, or “Fundamental River Law,” setting out the principles of 流れ (flow) and 毒 (poison) to show the vital importance of protecting nature from manmade pollution, he was also a progressive intellectual and agitator who, as editor of the Tochigi Shimbun, today’s Shimono Shimbun, propagated the works of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham. He was elected to the Diet in 1890, which itself shows that Japanese democracy was sufficiently developed to accommodate such a visionary in the “establishment.”

I was reminded of the 1901 petition to the emperor when Diet member Yamamoto Taro handed an anti-nuclear letter to the emperor in 2013, exactly a century after the death of Tanaka Shozo; and I was dismayed at the vilification poured on Yamamoto by the media. Not much has changed in a century. Perhaps in some ways Meiji Japan was even more tolerant of dissent than today’s Japan.

Just one more note on Tanaka Shozo, a quotation of his that rings true today.

「真の文明は、山を荒らさず、川を荒らさず、村を破らず、人を殺さざるべじ」 “A true civilization does not destroy mountains, defile rivers, tear apart villages or murder people.”

If any quotation from the Meiji era proves that the issues in which Takuboku and his contemporaries were deeply and personally involved are any different from those that affect us today, this one does. A society without vigorous polemics that reach the public through various forms of media is a society destined to stagnate.

The second incident affecting Takuboku, to an even greater degree, was that involving the socialist author, translator and journalist Kotoku Shusui, who was arrested for treason on trumped-up charges and executed together with others on January 24, 1911. This date has to be seen as an important moment marking the decline of Japanese democracy, a decline that took the country down the dark spiral staircase to the dungeon of defeat on August 15, 1945.

The cause and fate of Kotoku Shusui stunned Takuboku. Both men were enamored of the writings of the Russian scientist, philosopher and anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin, whose books were banned in Japan at the time. On June 15, 1911, less than half a year after the execution, Takuboku wrote the long poem that can be seen as a call to action to the young people of Japan, 「はてしなき議論の後」(“After Endless Argument”) in which he bemoaned the lack of activism in Japan, employing the Russian exhortation “V NAROD!”

V narod! is a call to action that has its roots in the middle of the 19th century, primarily as a feature of the anti-feudal philosophy of the Russian socialist Aleksandr Herzen. The principle was народничество (narodnichestvo), which means “unity with the people.” Those who held this belief were called “narodniki” and they advocated that activists of all sorts should “V narod!”, that is, “Go to the People!” This became the basis of Takuboku’s ideal of activism.

Yet despite his belief, he found himself unable to become an active protester, and he had pangs of conscience over this personal shortcoming. Even so, his honesty shines through. He admits his shortcomings and continues to support progressive people through his writing. In this sense, he is an activist. His self-searching introspection has a ring of truth to us today at a time when what is needed more than anything in Japan now is “endless argument.” Alas, we are getting the opposite: discussion and polemics that are truncated by authority and suppressed to serve a false sense of unity.

TRANSFORMATION

Takuboku’s transformation from provincial romantic to national firebrand came with the tumult of his times.

He was born in Iwate Prefecture on February 20, 1886, in a little village not far from Shibutami, where his family moved when he was one year old. Takuboku is a pen name; his given name was Hajime. His father was chief priest at a Buddhist temple. As an adult he longed for this home.

His hometown reminds him of the time he was a child; and most people look back to their childhood with deep emotions of one sort or another. To Takuboku such reminiscing usually brings tears to the eyes. The volume of tears in Takuboku’s tanka is large indeed. And he can be assaulted by them anywhere and be caught unawares. Suddenly an autumn wind will blow and he will be transported back home … and tears will flow, or if not tears, a flood of regrets.

Miyazawa Kenji, in that sense, is a much freer traveller. He is generally ecstatic when “on the road.” He is not always drawn home. Kenji looks outward to discover the world; Takuboku looks inward to discover the world. Both poets, however, are deeply affected by their own agitated mental state when they write. Both find joy in sadness and sadness in joy.

Both poets, too, are obsessed with modernity. Coming from what was a remote location in Japan at the time, trains and electric lights and all sorts of other inventions appear often in their works. Takuboku wrote his works in the late Meiji era; and Kenji in the Taisho and early Showa eras. But the presence of modern technology and its importance to their view of the world is equally strong. Theirs is not a nostalgia for the past per se. They are thoroughly modern men and they both believe in human progress, economic development and the social betterment of humankind. They may have been seen as being provincial by some people in Tokyo, but they are genuine forward-looking cosmopolitans.

Japanese people were more mobile in the Meiji era than at any other time in Japan’s modern history except, perhaps, for the years after World War II. (By mobile I mean frequently moving house, not travelling for pleasure.) Of course, many men in late Showa and Heisei Japan have been sent by their companies to other cities in Japan and the world. But this is hardly at their own initiation. In Meiji, men moved from one city to another, usually dragging their family along, in search of work. The Meiji Restoration saw great waves of upheaval in all aspects of social life, and people were carried on those waves. Large cities such as Tokyo and Osaka were the usual repositories for these waves of internal migrants, but many, especially people from Tohoku, went to other places, such as Hokkaido, which was to Japan what the West was to America, a place of opportunity where the indigenous population had been all but wiped out. So, there were few people already there with a stake to defend. Land and opportunity seemed waiting to be taken. In his 1923 poem “Asahikawa,” Kenji speaks of the horse-drawn carriage he is riding on through that town as being “in the colonial style.” Is it perhaps really the place and not the carriage, though, that he sees as “colonial”? Hokkaido was, in a sense, a colony, an outpost of Honshu at the time … and Takuboku was there 15 years before Kenji wrote that poem.

Mobility created the kind of atmosphere in Meiji Japan in which people felt insecure about their future but also felt freer than they did when, in the Showa era, moving around to seek employment was equated with being unsuccessful in a single steady job and with being “bad for the children.” Needless to say, with the exception of the rich, people had many fewer possessions than they do now. You could pack a few suitcases and move house rather easily. Perhaps Japan in the Meiji era was a much less materialistic society than it became after World War II.

Takuboku might have returned to his hometown had he lived longer. His reputation even when he was alive was huge. He could have moved back to Iwate with his family, maybe even taken up a teaching position in Morioka. But his life was short and he was destined to suffer for being away.

He attended primary school at Shibutami; and the school, with the very same classroom in which he sat, is beautifully preserved today in its natural setting alongside the museum dedicated to his life and work. He moved on to middle school in the Iwate prefectural capital, Morioka, where he first met and became infatuated with Horiai Setsuko. By age 16 he was producing work of such quality that his tanka were accepted by the premier tanka journal, “Myojo,” and he promptly dropped out of middle school to pursue a career in literature.

RECOGNITION

It wasn’t long before he was recognized by the likes of Yosano Tekkan and Akiko, the leading lights in the genre of tanka, as a brilliant new voice. At the beginning of May 1905 he published his first collection of poetry, 「あこがれ」(“Yearning”), and, at the end of the month, married Setsuko. The little home in Morioka that they moved into still stands and can be visited today. Takuboku, who was in Sendai scrounging loans from friends, had missed his own wedding, obliging his bride to wait at the marriage home for him until June 4. Since his parents and younger sister Mitsuko were also living at the house, the family discord that is a major theme of his poetry was to rear its head quite early on.

Setsuko gave birth to a daughter, Kyoko, at the end of December 1906. Adding to the domestic turbulence was the defrocking of his father for failing to pay dues to the temple, leaving Takuboku as the entire family’s breadwinner.

“Akogare,” a collection of 77 poems, is the kind of lyrical outpouring one would expect from a disaffected, sentimental and self-indulgent young man. He would not come into his own as the keenest observer of his life and times until 1910 and 1912, when his two major collections of tanka, 「一握の砂」 (“A Handful of Sand”) and 「悲しき玩具」 (“Sad Toys”) came out, respectively. The latter was published in June 1912, two months after his death.

In 1907 Takuboku travelled alone to Hakodate in Hokkaido, becoming a substitute teacher at a primary school. But the school burned down in a fire and he went to Sapporo, where, in August, he found work as a proofreader at a newspaper. By September he was in Otaru, this time writing for the Otaru Nippo. Alas, a violent altercation with the editor in December brought an abrupt end to that employment.

Takuboku moved to Tokyo in 1908, and the next year began working again as a proofreader, now at the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun. His wife, daughter and mother joined him there, but the atmosphere in the home was, at best, strained and, at worst, internecine. A son, Shinichi, was born to the couple in 1910, but the infant died three weeks after birth.

Takuboku himself was plagued by illness but could ill afford to see a doctor. He was urgently hospitalized in 1911 and diagnosed with chronic peritonitis, spending 40 days in hospital after surgery. His mother died of tuberculosis in March 1912; and on April 13, he passed away from the same illness, age 26.

|

Takuboku’s two daughters, Kyoko and Fusae. Courtesy of the Ishikawa Takuboku Memorial Museum. |

After his death, Setsuko took Kyoko to Awa in Chiba Prefecture, where she gave birth to another daughter, Fusae. In September of that year, she returned to her family home in Hakodate with the two girls. In March 1913, Takuboku’s ashes were brought to Hakodate and interred there. Setsuko died of TB in May of that year, age 28. The daughters succumbed to illness in December 3, 1930, Kyoko to pneumonia at age 23 and Fusae to TB at 18, both dying at a younger age than their parents were when they passed away.

Takuboku had begun writing diaries in 1902, the most famous of them being his 「ローマ字日記」 (“Diary in Roman Letters”), which he wrote in that script as an obstacle to his wife’s reading it and as an experiment to escape from the confines of orthodox Japanese style. In fact, his tanka taken together also loosely form a kind of diary of events, internal and external. Takuboku wrote that poetry itself was a report in detail of changes in an individual’s emotions. His diaries and his poetry are permeated with a searching self-examination. They are deep stabs at truth.

He fell hopelessly in love with a number of women, the most acclaimed in his poetry being Tachibana Chieko and the geisha Koyakko, whose real name was Konoe Jin. Ms. Tachibana, a fellow teacher in Hakodate, did not return his affection and married someone else. Takuboku was, after all, a married man. The truly beautiful Koyakko, however, had ardent feelings for him. She possessed an incisive intellect and recognized his talent. And surely she also possessed the most famous earlobes in literary history (see poems). Koyakko died in 1965, outliving her poet lover by 53 years.

|

Koyakko, geisha from Kushiro, Hokkaido. |

Takuboku likened pining for his hometown to illness, and he longed for the innocence that he had once wallowed in, for the ability to laugh and cry without being judged, for the freedom to express what he felt without fear of being censured.

While he was convalescing in hospital, visits by members of his family were special but awkward, as they can be in such circumstances. After all, Setsuko too had TB, and she was forced to carry on with her household duties though debilitated and unable to breathe properly.

In hospital Takuboku’s world shrank. Witness him in “The Patient” …

One push of the door, a single step

And the corridor seems to stretch

As far as the eye can see.

And yet he never lost his compassionate gaze, evident in another tanka about a patient written while convalescing.

I called out to him but he didn’t answer.

When I took a good look

The patient in the next bed was weeping.

Drugs and medical practices in his day often did more harm to patients than good. Takuboku took a drug called Pyramidon for his TB. This was a kind of anti-inflammatory that, needless to say, did not cure the disease. In fact, its side effects on the immune system could be serious; and in 1936 it was officially designated as a poison in Britain.

DEATH WISH

While it is not possible to make a certain diagnosis of Takuboku’s mental state, I do believe that he suffered from a form of depression. He also feigned illness, perhaps to give grounding to his intense feelings of self-pity. As if this weren’t enough of an excuse to stay away from work, he once inflicted harm on himself by cutting his chest with a razor, but thankfully was stopped by his friend Kindaichi Kyosuke. Kindaichi, ever the compassionate companion, pawned his overcoat and took the sulking Takuboku out for a tempura dinner accompanied by much alcohol.

Takuboku, from time to time, exhibited what is called in modern psychiatry a “death wish.” This is a desire to die expressed often, particularly in olden times, in romantic or heroic imagery. Many people saw a young death as somehow “beautiful.” Why not, for after all there were many of them. You may as well idealize young death if you are going to see it everywhere you look. Children who died were called “little angels.”

Takuboku idealizes the death of people he sees as political martyrs. If only he himself could die such a death instead of just wasting away! But if we look behind this, more deeply into his psyche, we see that there are serious signs of the kind of depression that triggers a death wish, particularly withdrawal from human contact and self-reproach.

Isn’t this precisely what we see in Japan a century later—young people who shy away from human contact, withdraw and tend to blame themselves, often erupting in sudden anger? Takuboku expressed these feelings with intense honesty.

Other modern writers have exhibited a death wish, a wish that, unlike Takuboku, they carried out. Akutagawa Ryunosuke and Arishima Takeo; Dazai Osamu, Mishima Yukio and Kawabata Yasunari. Though these writers differ in the method they chose to take their lives, they all experienced a profound despair, either over their personal condition or the state of society as they saw it (the latter is particularly strong in Mishima’s case). But none of these writers analyzed his condition or state of mind with the forthright candor that we see in the writing of Takuboku.

Takuboku wrote profoundly, in poetic terms, about the psychology of dreams. Carl Jung, the Swiss psychoanalyst, was just developing his ideas about the subconscious, introversion and extroversion around the time of Takuboku’s death. In fact, he published his ground-breaking book, “Psychology of the Unconscious,” in 1912, the year of Takuboku’s death.

Miyazawa Kenji used the term 「心象スケッチ」(mental sketches) to describe the poems he wrote. He insisted to the publisher of his only poetry collection that came out in his lifetime that it was not a collection of poems but rather “modified mental sketches.”

In a sense, Takuboku too writes “modified mental sketches.” But there seems to me to be a difference in approach between the two great poets of Iwate.

Kenji, for all his compassion for others, views the outside world through the prism of his own mental state. His descriptions of nature are not nature itself but the re-creation of nature in his mind. Kenji’s eye on the world and himself is utterly subjective in its essence.

Takuboku’s eye on the world and himself is, on the other hand, essentially objective. Of course, he is the subject who observes, so he cannot disassociate himself entirely from what he sees outside himself. No one can do that. But he strives to be objective, to tell the “truth” about the world of others as well as his own inner world. Kenji strives to teach us about how he himself views the world, and fervently wishes for us to enter his world (and accept his religious values).

For both poets, however, the poetic self is an illusion. But it is an illusion that is invented and reinvented time and time again with each discrete observation and experience. When all of these discrete illusions are put together, we receive a whole picture of the writer and his times.

Both poets accept the fact that their illusions of reality are made up. Kenji’s world is grounded in realism; and in my book 「賢治から、あなたへ」 I coined the term “Kenji realism” to describe his worldview. But this realism is only a launching pad for the rocket of his imagination.

As for Takuboku, he confesses in a tanka that he pictures himself as “a bundle of lies.” And in another tanka, to which I have given the title “In One Way or Another,” he confesses …

I picture myself

As a mass of lies.

I shut my eyes.

He admits that knowing or saying this gives him no comfort. And yet, it gives much comfort to us to read these revelations because, thanks to his frankness, they allow us to be more open and honest about ourselves, to question our own opinions and feelings. This is the value of Takuboku’s poetic objectivity. It is “Takuboku realism.”

Unambiguous empathy, deep introspection, stark sincerity, the aspiration to be close to people and share their plight, even if unable to embrace or march with them … these are the qualities created in poetry by Ishikawa Takuboku.

He is a model for today’s self-sequestered youth, with his ardent commitment to life and word, his constant seeking of something better for himself, his family, to whom he was devoted in his own way, and his care for people who found themselves living at the lower economic and social strata in his country.

And he is a model to all, not only for this candor and compassion, but for his insight into his own psyche and his willingness to share it unequivocally with us. There is nothing devious or calculating about Takuboku; and if such a tendency does show up, he is the first to put his finger on it and bathe it in a bright light.

In the mirror of his works we are compelled to examine the features of our own face in this bright and wholly revealing light as it reaches us, without diminishing, from another time.

|

The Illusions of Self: 200 Tanka by Ishikawa Takuboku Roger Pulvers’ collection of 200 translations of tanka by Takuboku was published in April by Kawade Shobo Shinsha under the Japanese title, 「英語で読む啄木 自己の幻想」. |

TANKA BY TAKUBOKU

|

Labor |

|

|

However long I work Life remains a trial. I just stare into my palms. |

はたらけど はたらけど猶わが生活楽にならざり じっと手を見る |

|

Revolution |

|

|

Nothing seems to disconcert my wife and friends More than my going on about revolution Even when struck down by illness. |

友も妻もかなしと思うらし 病みてもなお 革命のこと口に絶たねば |

|

The patient |

|

|

One push of the door, a single step And the corridor seems to stretch As far as the eye can see. |

ドア押してひと足出れば 病人の目にはてもなき 長廊下かな |

|

The patient |

|

|

I called out to him but he didn’t answer. When I took a good look The patient in the next bed was weeping. |

話しかけて返事のなきに よくみれば 泣いていたりき隣の患者 |

|

In one way or another |

|

|

I picture myself As a mass of lies. I shut my eyes. |

何となく 自分を嘘のかたまりの如く思いて 目をばつぶれる |

|

On a lark |

|

|

I lifted my mother onto my back. She was so light I wept Stopped dead after three steps. |

たはむれに母を背負いて そのあまり軽きに泣きて 三歩あゆまず |

|

Weather |

|

|

The rain brings out the worst In every single member of my family. Oh for one clear day! |

雨降れば わが家の人誰も誰も沈める顔す 雨晴れよれよかし |

|

Intentions |

|

|

A husband intent on getting away A wife intent on scolding, a child on bawling … Ah, the breakfast table! |

旅を思う夫の心 叱り、泣く、妻子の心 朝の食卓 |

|

Old love letters |

|

|

There are so many spelling mistakes In those old love letters. I never noticed until now. |

その頃は気つかざりし 仮名違いの多きことかな 昔の恋文 |

|

Words |

|

|

My daughter is picking up words like “Workers” and “Revolution” At the tender age of five. |

「労働者」「革命」などという言葉を 聞きおぼえたる 五歳の子かな |

|

Jesus |

|

|

It grieved me that my little sister Looked upon me with such pity When I said, “Jesus was just a man.” |

クリストを人なりといへば 妹の眼がかなしくも われをあはれむ |

|

Unforgettable |

|

|

I can’t get them out of my mind … Lovely Koyakko’s soft earlobes Among other things. |

小奴といひし女の やはらかき 耳朶なども忘れがたかり |

|

At the station |

|

|

I slip into the crowd Just to hear the accent Of my faraway home town. |

ふるさとの訛なつかし 停車場の人ごみの中に そを聴きにゆく |

|

Seeing off at the train station |

|

|

My wife came with our daughter on her back. I caught sight of her eyebrows Through a blanket of snow. |

子を負ひて 雪の吹き入る停車場に われ見送りし妻の眉かな |

|

The nasty carpenter’s son |

|

|

It’s saddening. Among many The young man went to war To come back dead. |

意地悪の大工の子などもかなしかり 戦に出でしが 生きてかへらず |

|

Indelible ink |

|

|

I hear the autumn wind blowing As I blacken in A map of Korea. |

地図の上 朝鮮国にくろぐろと墨をぬりつつ 秋風を聴く |

|

In the hospital |

|

|

Oh the joy of leaning out the window And for the first time in ages Catching sight of a policeman! |

病室の窓にもたれて 久しぶりに巡査を見たりと よろこべるかな |

|

Trembling |

|

|

I feel so sorry for the young nurse Dressed down by the doctor Because her hand trembled on my pulse. |

脈をとる手のふるいこそ かなしける 医者に叱られし若き看護婦 |

|

For some reason |

|

|

There is a cliff inside my head. And day by day a fragment of earth Crumbles off it. |

何がなしに 頭のなかに崖ありて 日毎に土のくづるるごとし |

Translated by Roger Pulvers.

Roger Pulvers is the author of more than 40 books in Japanese and English. His novel “The Dream of Lafcadio Hearn” is published by Kurodahan Press.His most recent book is Illusions of Self: 200 Tanka by Ishikawa Takuboku Translation, Notes and Commentary.

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Japan Times on April 12, 2015.

Recommended citation: Roger Pulvers, “Illusions of Self: The Life and Poetry of Ishikawa Takuboku”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 15, No. 2, April 13, 2015.

His profiles of major Japanese writers and thinkers include: The Life and Death of Lafcadio Hearn: A 110-year perspective and Miyazawa Kenji’s Prophetic Green Vision: Japan’s Great Writer/Poet on the 80th Anniversary of His Death