The Samurai Way of Baseball and the National Character Debate

By Robert Whiting

Introduction by Jeff Kingston

In this essay Robert Whiting does what he has done in best-selling books such as You Gotta Have Wa and The Chrysanthemum and the Bat—use baseball as a window on Japanese society. He draws on his experience of living in Japan for some four decades, and on thirty-five years of reporting on Japanese baseball for the Japanese press. In his work he has suggested that there are some distinctive traits and characteristics that Japanese ballplayers exhibit in their approach to the game. He has referred to this approach as “samurai baseball”—a term meant to convey succinctly and evocatively the discipline, devotion and sacrifice that can be seen on diamonds all over Japan, from school playgrounds up through the professional leagues. In Whiting’s view, one can understand aspects of national character in the way Japanese practice and play baseball. The frenzied year-round media coverage and the organized fan groups reflect an obsession with the game that peaks during high school baseball tournaments. In Japan, baseball is much more than a game.

Over the years, Whiting’s views on baseball and national character have drawn sustained criticism from William Kelly, an anthropologist at Yale University. Kelly finds “samurai baseball” an inadequate and misleading term, one that dresses up in the regalia of tradition what is essentially a set of traits that are modern in origin and function. The debate between these two keen observers of Japanese baseball speaks to the larger debate within Japanese studies about the issue of national character. Is it possible to discern a set of traits that can usefully be said to constitute a national character? If so, what is that character and how is it evinced? How does this national character debate relate to that concerning invented traditions? How do traditions, invented or selected, shape and permeate the modern? Does baseball suggest something about national identity? Is “samurai baseball” akin to “samba football” in relation to Brazilian-style soccer—a useful shorthand that succinctly evokes certain attributes that a general reading public can understand? What kind of embedded meanings might lurk within such terms?

On the eve of the 2006 World Cup, hosted by Germany in June, hopes ran high for the Japanese national team, which interestingly enough was called Samurai Blue. The media made a major event of baseball legend Sadaharu Oh signing the team banner just below the name.

This essay draws on a speech delivered a conference hosted by Michigan State University in April 2006, which was also attended by Kelly. In a cover letter that accompanied this essay, Whiting explained that his views have been misrepresented and that, in essence, he has served as a “straw man” in Kelly’s writing on Japanese baseball. Here the “straw man” responds. He writes, “William Kelly has attacked me in a long succession of articles on Japanese baseball in scholarly journals and other publications going back to the mid-90s; he even introduced the term ‘the Whiting Problem’ in one of them. Not one of the editors overseeing Professor Kelly’s work has ever asked me if I would like to respond. So I’m turning to Japan Focus for a chance to state my case and correct Kelly’s misrepresentations. Moreover, as it happens, Professor Kelly’s work also suffers from factual errors, serious misinterpretations and insufficient research. Since these shortcomings went unnoticed by the editors of the aforementioned journals, I would like an opportunity to correct the record on this score as well, lest these [Kelly’s] writings be taken as gospel by students of the game.”

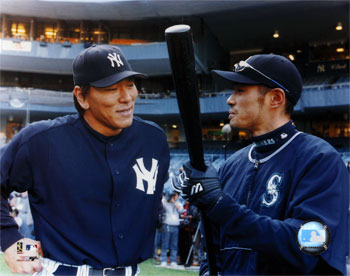

The success of players like Ichiro Suzuki and Hideki Matsui in the United States has once again demonstrated the power of sport in crossing national borders. With their stirring performances on America’s baseball diamonds, these imported players have helped to create vast new markets for Major League baseball in Japan, while teaching Americans that there is a new and very different way to approach their own national pastime. More importantly, the accomplishments of these athletes have served to influence the way many Americans and Japanese look at each other, and raised anew questions about the role of culture in sport.

Hideki Matsui and Ichiro Suzuki

Not so very long ago, there were executives in the highest echelons of American baseball who were still talking privately, in not very nice terms, about keeping those Japanese in their place. [1] But that attitude has seemingly changed in the wake of the impressive achievements of recent imports. Seattle Mariner Ichiro has put together an unprecedented string of 200-hit seasons, breaking George Sisler’s 84-year-old single-season-hits record, while spurring an influx of tourists from Japan that has brought millions of dollars into the Northwest area economy. Matsui has become a popular, reliable fixture in the New York Yankees outfield, while Tadahito Iguchi played such an important role on the 2005 World Champion Chicago White Sox squad that his manager Ozzie Guillen called him the real MVP of the team. The subsequent emergence of an enormous new market for Mariner, Yankee and White Sox telecasts in Japan has also helped. At the end of the 2003 season, Major League Baseball (MLB) signed a record $275-million TV contract with the giant Japanese advertising firm Dentsu, and then sent the Yankees and the Tampa Devil Rays to play an opening-day game in Tokyo in 2004. Moreover, the MLB and the Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA) enthusiastically promoted the establishment of the World Baseball Classic (WBC), a quadrennial tournament that debuted in March 2006, featuring national teams from 16 countries—with American organizers going to extraordinary lengths to coax an initially reluctant Japan to join in. All in all, that represents quite a transformation.

The Japanese team after winning WBC 2006

The Asahi Shimbun summed up the impact of these events in Japan by editorializing, “Japanese were once seen in the US as a ‘faceless’ people obsessed with exporting cars and consumer electronics. The excellent play of the Japanese baseball players and their positive personalities have changed the American image of the Japanese.” [2] Team WBC certainly helped solidify that new image.

Finally, it might be said that the Ichiro experience seems to have helped usher in a new era of acceptance of Americans in Japan. I can’t count the number of times that people—from ordinary fans to members of the journalistic profession—have expressed their surprise to me that during Ichiro’s ultimately successful quest to break Sisler’s single-season-hits record, the Japanese star received almost uniformly positive treatment by American fans and media. This was puzzling to them because it was in marked contrast to what American sluggers have experienced when chasing Japanese titles or attempting to break Japanese records.

For example, in 1965, Daryl Spencer was walked eight times in a row—once with his bat held upside down—when he threatened to become the first American to win a home run title in postwar Japan. Said pitcher Masaaki Koyama, who walked Spencer four times on 16 consecutive pitches, “Why should we let a foreigner take the title?” [3] Randy Bass, a big, bearded, popular Oklahoman, threatened ex-Giants star Sadaharu Oh’s single-season record of 54 home runs going into the last day of the season. But facing the Giants, then managed by Oh, at Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium, Bass too was walked intentionally in four out of five plate appearances, reaching base only when he stuck his bat out at an outside pitch for a fluke single to the outfield. Tuffy Rhodes received similar treatment in 2001. Playing for the Kintetsu Buffaloes, he was walked repeatedly in a late-season game against the Hawks of Fukuoka, also then managed by Oh. Said Hawks battery coach Yoshiaru Wakana, “It would be distasteful to see a foreign player break Oh’s record.” [4]

These incidents were indicative of a strain of anti-Americanism that existed in Japan in the postwar era. It has been one of the defining characteristics of the Japanese game since the early 1960s, when former Major League players began arriving on the scene in sizable numbers, with hefty salaries and equally hefty egos.

There was ambivalence about American managers in Japan, as well. Wally Yonamine, Joe Lutz and Don Blasingame, among a handful of others, managed in Japan but there was a certain amount of skepticism, because, among other things, their American-style philosophies on training and discipline were too moderate for most Japanese, accustomed as they were to a strict blood-and-guts approach to baseball. Blasingame’s departure in mid-season of 1980, after a policy dispute with the front office, prompted his Japanese replacement Futoshi Nakanishi to comment that Blasingame simply could not understand the Japanese way of thinking, while the Central League commissioner remarked, “Foreign managers are simply not suitable for Japan.” [5]

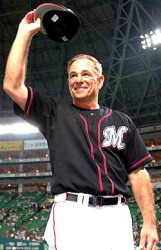

However, it is worth noting that by the end of 2005, with Japan basking in the glow of international goodwill inspired by America’s love of Ichiro, there were suddenly no less than three American managers in Nippon Professional Baseball (NPB), an unprecedented embarrassment of gaijin influence. The managers were led by Bobby Valentine, who became the first American to win a Japan Championship when his Chiba Lotte Marines swept the Hanshin Tigers in four straight games, after defeating the Softbank Fukuoka Hawks in a five-game playoff. Valentine did this with a modified American-style approach and it came, incidentally, a decade after he was fired by the same team after only a year on the job, and despite a strong second-place finish, because of “philosophical differences.”

Bobby Valentine

Valentine emphasized proper rest and short, snappy practices, focusing on individual instruction as opposed to the traditional way of group-based, rote learning. He also eschewed the kind of negativity seen in many Japanese clubs where praise is rare, harassment common, physical abuse not unheard-of, post-game hanseikai (self-reflection conferences) a daily occurrence, and special morning practice, along with banishment to the bench or the farm team, a frequent result of bad play.

At the end of the year, Valentine’s methods were being enthusiastically applauded in some circles. He was the only foreigner listed in a survey concerning the ideal boss, conducted by Macro Mill research company. A newspaper editorial by the president of Nippon Metal called on Japanese firms to curb their tradition of harsh management and overwork and begin treating employees the same way Valentine does. [6]

However, Valentine’s ways did not win him any friends among Japanese traditionalists. In the summer of 2005, the Shukan Asahi published an article accusing Lotte players of drug use. There was no hard evidence, but in the piece, former Lotte executive Tatsuro Hirooka—the man who had once fired Valentine—was quoted as saying, “The players on Lotte are no good. They don’t practice hard. So the reason they are winning must be drugs.” [7]

When spring training started in 2006, the foreign-managed teams practiced from 10 a.m. to 1:30 p.m., as MLB teams are wont to do, after which the players were left to their own devices, which often meant hanging around for individual instruction or simply going home. By contrast, the teams run by Japanese managers practiced as a group until 3 p.m. or 4 p.m., or longer, as NPB teams traditionally do, focusing on the finer points of team play: relay drills, sign plays, the push bunt and so forth. Venerable Katsuya Nomura, age 70, new manager of the Rakuten Golden Eagles, made his charges swing the bat a tiring 1,000 times a day in practice and forced his pitchers to throw as many as an arm-numbing 300 pitches in one go. Legendary slugger Sadaharu Oh, manager of the Softbank Hawks, was just as tough (except for the hair policy), and his veteran stars went even further on their own: his slugging first baseman Nobuhiko Matsunaka started his day lifting weights at 9 a.m. and finished up at 6 p.m., after a solid hour of swinging the bat. Also, during the season, most Japanese-managed teams practiced more, with lengthier pregame workouts, longer pregame meetings and travel on practice days—something not done in the MLB.

Meanwhile, across the sea, hardworking Ichiro, famous for his lengthy camp and pregame workouts, had taken his Seattle teammates to task for their overall lack of preparation and commitment, and was trying to get his manager to adopt more Japanese-style methods.

Indeed, the smooth, much-praised performance of Team Japan in WBC 2006, an event that was widely watched in Japan, caused many Japanese baseball experts to conclude that after all, their way was best. The manager of Team Japan was none other than the aforementioned Oh, a man whose name was synonymous with backbreaking workouts during a storied career in which he hit 868 home runs.

Sadaharu Oh at WBC 2006

Samurai Baseball

The brand of baseball Japanese play starts as early as Little League, with games and practice 11 months a year. Ichiro began daily workouts with his father at age 7. In high school, he lived in a team dormitory and underwent a round-the-clock regimen that included corporal punishment; it was three years of work that he called the “hardest thing I’ve ever done.” His pro camps with the Orix Blue Wave in Japan resembled basic training for the Marines. Today, he still works harder than anyone else on the Seattle Mariners team. He is the first one at the park, arriving at 1:30, and undergoes a demanding pregame workout routine of tee batting, stretching, running and throwing that has his teammates in awe.

The system in Japan dates back to the 19th century and has been called samurai besuboru by many participants. Some critics object to this appellation as too simplistic and scoff that players of today bear as much resemblance to the warriors of the past as the Marlboro man does to the original cowboy. But that is a false comparison, for it ignores the very real similarities and the grounding that the game has in budo or bugei, the martial arts of old, and its relationship to bushido with its lessons about dedication, self-perfection, submergence of ego and development of inner strength. These are lessons that apply to life as well as sports and have been passed down from generation to generation by fathers, teachers, coaches and, in adulthood, corporate bosses, right to the present day.

Baseball was introduced early in the Meiji era by American professors and became popular when the First Higher School of Tokyo, an elite prep school for students aged 18–22, defeated a team of Americans from the Yokohama Country and Athletic Club in a series of games in 1896, which received wide press coverage and turned the players into nationwide heroes. Ichiko, as the school team was known, was managed by a 26-year-old named Kanae Chuman, a former player, who believed that his team should ignore the American way of playing and devise a system that suited Japanese. This involved a year-round, often bloodstained training regimen, and two to three months of practice before a team played its first game. It centered around the martial arts idea that training, as demonstrated by famed judo teacher Jigoro Kano [8] years earlier, should be an ordeal the player must endure to strengthen him mentally as well as physically. Chuman’s star player Jitsuzo Aoi was known for a 1,000-swing drill performed at night in the team dormitory. It evoked associations with, among others, famed 17th-century swordsman Musashi Miyamoto, who, in his classic work, The Book of the Five Rings, preached the Way of the Martial Arts, exhorting devotees to “put into practice morning and evening, day in and day out.” “Surpass today what you were yesterday,” he wrote. “See to it that you temper yourself with one thousand days of practice and refine yourself with ten thousand days of training.” This approach was also evocative of the Itto and Yagyu schools of swordsmanship dating back more than 500 years.

A commemorative work published by the Alumni Association of Ichiko in 1903 carried this introduction by an Ichiko alumnus, which clearly stated what the baseball players were doing: “Sports came from the West. In Ichiko baseball, we were playing sports, but we were also putting the spirit of Japan into it . . . Yakyu (i.e., baseball, “field ball”) is a way to express the samurai spirit. To play baseball is to develop this spirit. Thus our members were just like the warriors of old with their samurai spirit.” [9]

Record of game between Ichiko and the

Yokohama Amateur Foreigners Club,

circa 1896. The final score is 32 to 9.

In the early part of the 20th century, Waseda’s Suishu Tobita, the most influential college baseball manager in the history of Japan, copied the Ichiko system, which he called “bushido baseball,” and which he declared was “the only true form of the game.” He invoked concepts of loyalty, courage and honor and exhorted his players to “practice until you die,” or at least until they had “collapsed on the ground and froth was coming out of their mouths.” [10] Waseda graduate and Tobita acolyte Sadayoshi Fujimoto, who became manager of the Tokyo Giants when professional baseball was established in 1936, led his team through a camp solely designed to hone the players’ fighting spirit, not their baseball skills. It was so hard that it was nicknamed “vomit camp.” It made what the New York Yankees went through seem like a spring vacation. Wrote one Giants historian, “It was from the mud and sweat of this training that the soul of Giants was born.” Practice at the Hanshin Tigers camp in Osaka was similarly intense, and featured participants walking barefoot on the upturned edge of a long samurai sword, in an exhibition of mental control. [11]

With some exceptions, subsequent managers in the professional as well as the amateur ranks have followed this system, or variations thereof, as they attempt to catch and surpass the standard of play set by Major League baseball. Tetsuharu Kawakami, the most famous postwar manager in the pros, and one of the strictest, played for the aforementioned Fujimoto. Like Tobita and many others, he thought the study of Zen an important tool for training his players. Kawakami star players Tatsuro Hirooka, Shigeo Nagashima and Sadaharu Oh all went on to become successful managers. They were famous for their own “hell camps” and their respect for bushido. Hirooka and Oh practiced Zen while Nagashima favored spiritual retreats to the mountains to hone mental strength.

This history is the reason that pre-season pro camps in Japan today are twice as long and twice as tough as their major league counterparts. It is also why some Japanese pro teams hold intense “autumn camps,” something Major Leaguers do not do. These harsh camps, like the kangeiko in judo, are a character-building ordeal to be endured, with 1,000-fungo drills, marathon runs and other sadomasochistic methods of honing spirit and mental strength. The Yomiuri Giants farm team started off the first day of autumn camp in October 2005 with 10 hours of practice.

There have, of course, been exceptions to the rule, like the freewheeling, nightlife-loving Nishitetsu Lions of the early ‘60s, who managed to win while having fun.But the Ichiko-Tobita system, and variations thereof, remained the most popular because it was the most successful and the most in-tune, ostensibly, with Japanese sensibilities. In 2004, a team of Fuji-Sankei reporters conducted an informal analysis of all pro managers since 1936 (there were 105 at the time) and came to the conclusion that some 90% of them were believers in, or followers of, seishin yakyu (or “spirit baseball”), as the system was also called. [12] Managers and coaches, they concluded, were simply continuing the demanding routines they had been subjected to from high school on up.

There are other reasons critics dislike the samurai/martial arts metaphor applied to baseball. They point to the fact that the professional leagues allow ties, instead of battling to the end, and ask where the samurai-like loyalty is in players who change teams. They charge that the artificiality of conjured-up images of bat-swinging samurais will jeopardize our understanding of Japan—a complex, densely populated country with a long history—perpetuate the stereotype of groupthink fascist collective baseball, and cause a “flattening of heterogeneity in favor of neat and unequivocal contrasts and Benedictian oppositional dyads,” to use some of the academic lingo that seems to be in vogue. But these arguments seem to me to be beside the point. And nitpicking. Ball players in Japan don’t wear kimonos or top knots either. They don’t carry swords. They don’t commit harakiri (although more than a few young players have been driven to mental hospitals by the demands of their coaches, and some have even died from the shock of the experience). And unlike the warriors of old, they don’t sleep with children in their free time—or at least I don’t think they do. Not openly.

The metaphor may not be perfect, but metaphor means resemblance, and so we must consider the ways in which it does fit—which means portraying the concepts of constant training, perfectionism and development of spirit to overcome physical limitations. To this writer, these characteristics represent the primary virtues of the samurai and the reasons why Japanese players are better conditioned than their American (North, Central and South) counterparts and are better at the fundamentals of the game. They are seen in the year-round training system, which shows no signs of abatement. It is not too much to say that baseball practice of 2006 in Japan is fundamentally not all that different from baseball practice of 1896 in tone and even content. It’s been part of the secondary school curriculum for that long (and part of the pros since 1936). By and large the system has remained because it works. The team that bleeds most, generally speaking, wins, those managed by Valentine and a few others aside. Indeed, players today may take as many as a thousand swings a day in camp and require two to three months to get ready for the reason, just like their ancestors did a century ago—citing samurai influence.

Moreover, demonstrations of loyalty, another samurai virtue, and the importance placed on human relations are seen—again and again and again—not only in high school and college but in the pros, as well. Recently deceased Motoshi Fujita, who played and managed for the Yomiuri Giants in a long career, first joined the team in the 1950s solely because his college senpai Shigeru Mizuhara assumed the managerial helm and “ordered” him to sign up with the club. Fujita pitched so often and with so little rest that he not infrequently collapsed in his genkan from exhaustion. But he never complained, even though a subsequent sore arm forced him into early retirement. [13] Star pitcher Hideo Nomo rebelled against the pitch-until-your-arm-falls-off philosophy of his Japanese manager Keiishi Suzuki, and defected to the US (incurring lasting enmity in the process), but Ichiro, who could have followed the same path, delayed his departure to the Major Leagues out of fealty to his manager, Akira Ogi of the Orix Blue Wave. Certainly the actions of those pitchers who refused to throw strikes to Bass, Rhodes and Cabrera reflected a certain kind of fealty to the boss.

Further evidence of the difference between the US and Japan in this regard lies in the fact that the Japanese players union is far more compliant than its aggressive US counterpart, and the movement of free agents from one team to another, though gradually increasing, is a fraction of what it is in the US. Unlike its American counterpart, the MLBPA, the NPBPA refused to strike for many years because it would be “unfair to the fans and the owners,” as union head Kiyoshi Nakahata put it back in 1986. Only strong public opposition to a merger of two teams in 2004 finally convinced the union to stage a first-ever walkout in September of that year—“in support of the fans” as NPBPA press releases put it. Even then, it lasted but two days and was accompanied by tearful public apologies, free autograph sessions and complimentary baseball clinics for kids over that historic weekend, by way of compensation. American MLB representatives who observed the scene could only smile in bemusement, and perhaps envy.

Whether players see themselves as samurai is beside the point (although some players, like Norihiro Nakamura of Orix, have the ideograph for samurai proudly written on their gloves); the historical connection is clearly there and the term an appropriate shorthand for a way of approaching a game that is significantly different from the way it’s played and practiced in America.

National Character

If bushido is a metaphor for baseball, however imperfect, then baseball is similarly a metaphor for Japanese society. Look hard at Japanese baseball and you can see the corporate concepts of unpaid overtime, karoshi (death from overwork), and group wa or harmony achieved through daily meetings. As Carol Gluck has pointed out, the code of bushido was seen in some quarters as the ethical model for rural 19th-century Japan, where hard work, cooperation and obedience to the village headman were paramount. [14] Donald Rhoden has written that baseball in 1896 “nourished the traditional virtues of loyalty, honor and courage symbolized in the ‘new bushido’ spirit of the age” and further “nourished those values celebrated in rural Japan and the civic rituals of state: order, harmony, perseverance and restraint.“ [15] Such values were reflected in the Imperial Rescripts on Education and after that in the big corporations and small businesses of modern Japan, as well as in the government bureaucracies and even the yakuza underworld. Moreover, Eiko Ikegami, in her seminal books The Taming of the Samurai and Bonds of Civility, contributed significantly to our understanding about the lingering influence of the samurai ethos in modern Japan—which, incidentally, was seen as recently as March 2006, when Kozo Watanabe, chairman of the Democratic Party of Japan’s Diet Affairs committee, called on his subordinate Hisayasu Nagata, who was embroiled in controversy over falsely accusing the Secretary-General of the LDP of accepting a bribe, to “act like a samurai and resign.” Watanabe recalled the story of the Byakkotai (White Tiger Squad); after losing a battle against the government in 1868, this band of samurai loyal to their feudal lord killed themselves. [16]

If there is one thing that baseball players, businessmen, bureaucrats, bartenders, beauticians, and boryokudan of the modern age have in common, it is that they come from a primary and secondary school system that emphasizes uniformity, submergence of self-interest to that of the group, and gambaru seishin (all-out spirit, making the great effort, gutting it out). The thought processes behind “study until your eyes bleed,” “work until you drop,” “practice until you die” and “the nail that sticks up gets hammered down” all came from the same source.

I remember the great surprise my Japanese brother-in-law, a chemical engineer assigned to his firm’s Washington, DC branch, experienced when he attended the first day of school with his children in a Virginia primary school and they were required to stand up, along with every other student in class, and describe what made them different from others. “In Japan it would never happen,” he said. “Kids are all taught to be the same as everyone else.” [17]

Indeed, students in most schools in Japan are trained to listen quietly, to not disturb the teacher with questions and to not express their opinions. They live in a culture of rules and of superior-subordinate status relationships that prepare them for entry into adult society, with all its strictures and behavioral codes—some of which hearken back to the Tokugawa era.

Students are also immersed in a method of learning that emphasizes repetition and perfection of minutiae. Students learn to write ideographs in a certain way, to arrange flowers in a certain way, and to swing a kendo stick or a baseball bat in similarly prescribed forms. This modus operandi naturally carries over into their adult work environment.

I’m familiar with the arguments of the anti-culturalists. I admit the concept of “national character” is ofttimes used by racists or as a stereotype that doesn’t go very far in explaining the actions of a country’s citizens very deeply. No one should argue that Japanese behavior is instinctive, unique or without internal contradictions, but to suggest that there is nothing different about the way that the average Japanese and average American see the world, and the way they articulate and act out values in a given situation, is to deny reality and throw the baby out with the bathwater. There is something more going on with the 1,000-fungo drill than “personal competition among individual players caused by the small scale of Japanese pro ball and the corporate ownership,” as some have written. What label you want to give it can be debated, and maybe “national character” is a passé term, but something else is going on and it’s not “ideological decisions made in particular circumstances,” as William Kelly of Yale has put it.

Of course, things change. Jet travel, satellite TV and the Internet have all served to lessen Japan’s relative isolation, blurring the differences and distinctions between the two countries. Players have become more Americanized. The departure of superstars to the MLB, something once unthinkable, has brought about great change. But at the same time, you can still bet that 99% of the players will show up for voluntary spring training in January and endure dawn-to-dusk training camps. And there is a reason for that, just as there is a reason that most Japanese will put in unpaid overtime or hang around the office after quitting time just to avoid being the first one to go home. These gestures matter.

Since the samurai approach is still pervasive (indeed, one will often hear that once Valentine and the other gaijin managers depart Japan, Japanese baseball will return completely to the old ways), it seems a useful metaphor for understanding society and the way people view the world and act in it. People may attribute different characteristics to samurai based on contemporary mores—witness the Shinsengumi’s metrosexual samurai—but there is a general sense of what those attributes are or should be and a sense that they are virtuous and worth emulating. Naturally, there is a gap between ideal construct and everyday practice, but there are clearly broad influences. I do think that the gut-it-out approach to life, school and work is still quite common in Japan, and that such gestures are still expected and offered because they matter—as an ideal, albeit one increasingly observed in the breach.

Setting the Record Straight

Finally, in this context, I would like to say something about the voluminous writings of Professor Kelly, the highly regarded Yale anthropologist, and frequent critic of my work. I respect Professor Kelly’s scholarship and I admire his effort to put together an academic history of Japanese baseball. At the same time, however, I must say that I find some of his interpretations of the game in Japan uninformed and believe that they undermine Americans’ understanding of it. Professor Kelly’s account of fan behavior and his gattsu genealogy are two examples that I discussed in The Meaning of Ichiro (see pp. 284–288 for the former and for the latter, Chapter 3 and p.280). [19]

Kelly’s remarks on the autocratic Tetsuharu Kawakami represent another misinterpretation. In an essay on Sadaharu Oh, “Learning to Swing in Japanese Baseball,” published by Cambridge University, Professor Kelly writes the following:

Japanese organizations’ suppression of individual initiative and selfless commitment to group objectives have always been stereotypic pieties mouthed by corporate flacks and accepted at face value by outside commentators and critics. In fact, however, postwar large organizations have always been defined by the continual tensions between the variable talents and motivations of individual members and multiple (even inconsistent) aims of the hierarchically structured group. Group harmony, hierarchical authority and individual motivation have always coexisted uneasily in Japanese organizations, like organizations everywhere.

This was certainly the case with the Yomiuri Giants, despite their carefully polished image of “managed baseball.” Indeed, it was well known that despite that phrase, manager Kawakami actually stressed individual effort to the players . . . (As Sadaharu Oh said,) “‘Kawakami baseball’ was generally thought of as team-oriented rather than individual-oriented . . . Play with greed for victory, he taught, and this he most particularly emphasized as an individual thing. One strove for the highest individual goals possible and did so relentlessly. He had an obligation to the team, but his obligation was best fulfilled by learning to use ourselves individually to the limit.”

Self-sacrifice, one might say, is a rather more complex disposition than that of a ‘cardboard samurai’—and rather more like definitions of effort familiar to athletes in the United States and elsewhere. [20]

Tetsuharu Kawakami baseball card

To imply that the Machiavellian Kawakami stressed individual achievement is to stand the term on its head. Kawakami was famous for saying that individualism would destroy a team, that lone wolves were a cancer in any organization, and demanding that his players all train the same way with the same intensity. What’s more, he regularly condoned the use of physical force on younger Giants players, by his coaches, to keep them in line. His dictatorial, harsh ways caused, in one infamous case, the nervous breakdown of a 20-year old pitcher, Toshiko Yuguchi, who entered a mental hospital in December 1972, after two years under Kawakami’s iron hand. [21]

Kawakami was among the league leaders in sacrifice bunts, despite having the most powerful 1-2 punch in Japanese baseball history in Oh and legendary third baseman Shigeo Nagashima. This strategy of sacrifice bunting at the earliest opportunity all too often left first base open when Oh came to bat, resulting in an inevitable walk, and literally taking the bat out of his star slugger’s hands. This practice, not uncommon in Japan but generally considered counterproductive in MLB by both managers and players, may well have prevented the great Oh from reaching the lofty 1,000 career home runs mark.

Veteran observers recall the time, early in the 1973 season, when Kawakami removed his ace pitcher Tsuneo Horiuchi in the fifth inning of a game with two out, nobody on and a 10-run lead, thereby depriving Horiuchi of credit for the official win. It was something no MLB manager would do, but Kawakami did so, it was believed, to demonstrate his power and teach Horiuchi—known for his surliness—a lesson in humility. Horiuchi was surprised, but he did not protest. At the same time, Kawakami also overworked his star, using him as a starter and in relief, in a way that won pennants, but damaged Horiuchi’s arm and put an early end to his career. Horiuchi may have had individual goals, but he was resigned to the fact that he would have little say in how he was used. All in all, Kawakami’s regime was not quite “like organizations everywhere.”

Next, consider Professor Kelly’s recent essay “Baseball in Japan: The National Pastime Beyond National Character,” in which he slams the New York Times for its headline on the aforementioned Randy Bass incident, which read, “The Japanese Protect Oh’s Record.” Kelly writes, “It was not the Japanese who walked Bass, but rather the Giants pitchers, and I think they had more reason for doing so than the simple fact that they were Japanese.” The first reason he cites goes as follows:

. . . the Giants wanted to win that final game very much, because they could salvage some pride by clinching the season series against their bitter, long-standing rivals, the Tigers. One cannot exaggerate the intensity of what was for decades not only a rivalry of teams, but also the pitting of second-city Osaka pride against the national-capital dominance, That year, the Giants had been preseason favorites to win the league title but slipped disappointingly and embarrassingly, while the Tigers were celebrating a rare success. With the Giants desperate for a victory, it was obvious strategy for them to pitch around the Tigers’ most potent hitter, who nevertheless became the second foreigner to win the Triple Crown. [22]

Randy Bass

While one might take mild objection to the generalization evident in the Times headline, it is inaccurate to say that “pitching around Bass” was an “obvious strategy.” The 1985 Hanshin Tigers had perhaps the most potent batting lineup in the history of the Japanese game. Bass hit in the third slot in the order. Batting fourth behind Bass was third baseman Masayuki Kakefu, who hit 40 home runs, 108 RBIs and a batting average of .300. Hitting fifth after Kakefu was second baseman Akinobu Okada with 35 home runs, 101 RBIs and a .342 average. (Hitting leadoff was right fielder Akinobu Mayumi who had 34 homers, 84 RBIs and a batting average of .322.) Putting Bass on base with such dangerous hitters coming up was tantamount to throwing the game, which was perhaps why the Giants lost 10-2. The argument looks even more suspect when one considers the details of each at-bat. In the first inning of the then-scoreless game, Bass came up with one out and a runner on base, only to be walked on four straight pitches, a violation of the baseball canon that says never put the lead run in scoring position. Next, Bass led off the fourth inning, with the Tigers trailing 1-0, and was walked intentionally again, this time in violation of the baseball canon that says do not put the tying run on base. In the sixth inning of that game, Bass came up to bat again with a runner on first, none out, and the Tigers still trailing 1-0. Incredibly, Giant starter Masaaki Saito, a young phenom who was leading the team in wins, tried to walk him for a third consecutive time. Bass threw his bat at a pitch well out of the strike zone and hit a fluke single to left. Kaekefu then singled and the Tigers went on to score 7 runs. Bass came up for his second at-bat of the inning with another runner on first base, and was walked yet again intentionally. In the eighth inning, he was given a fourth intentional pass—in this instance with runners on first and second base and the Tigers leading 7-2. Kakefu singled and the Tigers extended the lead to 10-2.

To call that “obvious strategy” for a team “desperate” to win the final game is the sort of disinformation one frequently gets from Yomiuri Giants front-office executives on loan from the Yomiuri Shimbun head office and who are not entirely versed in the game. Such an explanation falls in the same category as the blatantly false and inflated attendance figures the Giants have regularly reported over the years, which veteran sportswriters greet with laughter. It was also characteristic of the sort of propaganda that Foreign Ministry officials would feed foreign journalists to explain away the closed kisha (reporters) club system in Japan which effectively denies non-Japanese correspondents access to important press conferences.

Professor Kelly goes on to discuss other factors:

Furthermore, the record the Giants’ pitchers were protecting belongs to their manager, who was standing in the dugout watching them. Manager Oh was perhaps remembering another controversial game against the Tigers from his own playing days, when Oh himself was thrown at twice by the Tigers’ pitching ace, Gene Bacque, known as the “Ragin’ Cajun.” The second time Bacque threw at Oh produced a bench-clearing brawl, during which Oh’s batting coach, Arakawa Hiroshi, stormed the mound and was punched out by Bacque. Perhaps, too, Oh and his pitchers were recalling the belittlement of Oh’s career home run record by the American baseball world.

Most baseball fans, Japanese and American, felt it was unfortunate that the Giants pitchers avoided pitching to Bass. But the incident was much more revealing about the Giants, the Tigers and that season than it was about the Japanese as a people. Personal histories, bitter team rivalries, city pride, and our nations’ past interactions were all part of what happened that evening. A simplistic interpretation solely in the context of a broad-brushed national character is not an explanation. A love of the game and its pleasures should encourage us to appreciate the subtleties of baseball in Japan with the same knowledge and passion that we bring to the sport here at home.

I agree with this, but it is in the subtleties that I find Kelly’s analysis lacking, for here again, there are distortions. For example, anyone who knows Oh knows that he and Bacque were friends and that they often visited each other’s houses, before and after the incident. The one who flew into a rage was not Oh, who simply strode out toward the mound to tell his friend to stop throwing inside, but Oh’s mentor Arakawa.

And as for the argument that walking Bass was payback for Oh’s record of 868 homers being belittled in the American baseball world, that too is hard to swallow. In fact, Oh’s achievements won him the cover of Sports Illustrated, a front page story in the Washington Post, a special display in the Hall of Fame at Cooperstown, and kudos from every major leaguer who had seen him play, including Ted Williams, Hank Aaron and Clete Boyer. Oh himself has repeatedly said that his achievement should not be compared with those of MLB record holders because the two games are so significantly different that it is difficult to make any conclusive comparisons. One glaring example was that the compressed bats that Oh used were outlawed in the States because it was believed they gave the batter an unfair advantage.

In addition, anyone who knows the ever fair-minded Oh would know that he would never issue such a walk order to his pitchers. When Oh said that he had given no such orders to his staff to protect his record by intentionally walking Bass, he was widely believed. But also, anyone who knows Oh would also know that he would never countermand such an order from the front office. That would be disrespectful. Nor would he ever prevent his players from doing so on their own, out of respect for the tribute they would be paying him.

That the Giants wanted to protect their team record is certain. Indeed, walking the opposition to protect a team record has been a common if unsavory practice in Japanese baseball, and if Oh’s challenger had been Kakefu or Okada, those hitters would have been walked as well. American Keith Comstock, who pitched for the Giants that year, says he was told by a team coach that there would be a fine of a thousand dollars for every strike thrown to Bass, and most close observers believed those orders came from the front office. [24] But when a foreign player is involved, there is usually more at work than mere team loyalty, or at least there was then. How “most Japanese fans” felt about Bass’s treatment is not entirely clear despite Professor Kelly’s claim that most of them thought it “unfortunate” the Giants pitchers avoided pitching to Bass. But having been on the ground and in the trenches, covering Japanese baseball during that era, I can make an educated guess about the “national mood” at that time. Government surveys annually showed that roughly two-thirds of Japanese did not want to associate with foreigners, with only about one-fourth of the public favorably disposed toward the idea of marriage with a non-Japanese. Moreover, the 1980s were a time of intense anti-American feeling, because of trade friction with the US, among other factors, and there had also been much criticism of American ballplayers after a series of high-profile walkouts by noted ex-big-leaguers who were dissatisfied with their playing conditions. The Commissioner of Baseball at the time of the Bass affair, Takezo Shimoda, a former ambassador to the U.S., was openly hostile to American players. He was famous for saying that foreign players didn’t belong in the game in Japan, a remarkable statement for an ex-diplomat of such standing. “The gaijin are overpaid, underproductive and generally annoying,” he had said, this despite the presence of many well-mannered players from North America who more than earned their salary, like the easygoing Bass. [25] In 1983, Shimoda had even made the rounds of spring training camps, urging Japanese players to stop depending on their foreign teammates. “After all,” he said, getting down to the heart of the matter, “it is only natural that Japanese baseball be played by Japanese alone, as the gap between the respective levels of the Japan and American games narrows. Japanese baseball will never be considered first-rate as long as there are former major leaguers no longer wanted in their own countries in key spots in the Japanese lineup.” [26] Randy Bass, a former MLB benchwarmer, was one such player. Shimoda, one is sure, did not feel it was “unfortunate” that the Giants pitchers avoided pitching to Bass. Nor did the folks over at the right-wing-leaning Sankei Supotsu, which had previously published a baseball series entitled “Time of Peril,” calling for a total ban on foreign players. In one article the Sankei reporter had written, “What the Japanese fans really want to see is a big home run by a Japanese star, not a gaijin.” [27]

The smaller-than-usual afternoon crowd of 30,000, cheated out of an epic confrontation between Bass and Giants ace Masaaki Saito, certainly protested the walks to Bass, but most of those fans were there to support the Hanshin contingent and Bass, and the booing did not begin until the fourth walk. Moreover, retired Hanshin slugger Koichi Tabuchi, nicknamed “Mr. Tiger” for his prodigious home run output with that team and a man who, as a Tiger alumnus, should have been rooting for Bass, instead sympathized with the opposing faction.

“It was us against them,” he said later. “I played in the same era as Oh and we felt very strongly about his record. At the time, I would confess that people did not want anyone other than a Japanese to break the record.” [28]

Further evidence of this was seen in the contemporary coverage of the Bass incident. Although a column in a late evening edition of the Asahi Shimbun, Yomiuri’s arch rival, criticized the behavior of the Giants pitchers, sports papers the next morning were curiously devoid of outraged editorials or indignant quotes from fans and prominent NPB personages about the matter, including, of course, the commissioner.

Rules existing at the time already limited foreign participation in the regular season to two players per team and in All-Star games as well, a restriction that often kept league leaders from appearing. (The limit is now four.) Although such rules did not exist in the MLB, where there was a substantial Latin American contingent, few were protesting their existence in Japan.

In September 1986, the Asahi Shimbun conducted a survey that asked the question, “Are foreigners necessary?” 56% of the fans said yes. But only 10% of the players, four of the team owners and none of the managers said yes. The main complaint was not that foreigners cost too much money or deprived younger players of a spot on a team or even that they caused too much trouble. It was simply a Delphic “Japanese-only teams are ideal.” In 1987, new NPB commissioner Juhei Takeuchi declared flatly, “Pure-blooded baseball is ideal. We have to have a World Series between the Japanese and the Americans. We can’t do that with foreign players here.” [29] Yomiuri Shimbun chairman Risaku Mutai made similar statements throughout the 80s. [30] And in 1999, Giants manger Shigeo Nagashima, Japan’s national idol, declared to a group of supporters that his “ideal” for many years had been to field a purely made-in-Japan lineup. [31] A manager in MLB making such borderline racist remarks would no doubt be censured or perhaps fired. Predictably, no one in the Japanese press or the NPB raised a voice to object about the remarks.

As mentioned earlier, when Ichiro moved to the MLB the situation appeared to have changed. The aforementioned Tabuchi sensed this as well. He said, “Back then, the game seemed like the Japanese versus the US. But now, with Ichiro and Sasaki, people are watching a lot of American ball and have gained a real appreciation for it. There’s no prejudice anymore.” [32] In fact, Randy Bass had even written a letter to Tuffy Rhodes during the 2001 season, when Rhodes was threatening Oh’s record, saying essentially the same thing and telling him his chances for success were much better than in Bass’s time.

As we have seen, this turned out not to be the case. But at least the NPB commissioner on watch at the time, Hiromori Kawashima, was willing to denounce the unsportsmanlike behavior that prevented Rhodes from succeeding in his quest for the record. He issued a statement that said, “The decision of the Hawks to walk Rhodes was completely divorced from the essence of baseball, which values the supremacy of fair play.” [33] This was in sharp contrast to the statements of his predecessor and appeared to be widely supported by the fans. However, Rhodes left Japan convinced that there was a “code red” that kicked into action whenever a foreign player did too well. [34]

In conclusion, it is ironic perhaps that although anthropologists are trained to see through the surface appearances of society, in this case, Professor Kelly, normally a highly sophisticated observer of the scene in Japan, seems, however understandably, to have been taken in by them, while missing the fundamental realities. If we are going to talk about US-Japan relations, then we should address the dark side, for it certainly exists.

Xenophobia may be slowly dying out, but it has not yet disappeared. Nor has Japan’s “national character.” Baseball is still a good window for looking at both of them. [35]

Notes

[1] Remarks of this nature were first heard in the midst of lengthy, heated meetings between MLB and MLBPA officials in regard to the contract of Hideki Irabu, during the winter of 1995–96. San Diego had claimed the right to Irabu’s services via a trade with Irabu’s former team, the Chiba Lotte Marines, at the end of the ’95 season. Irabu claimed the trade was illegal, that it amounted to “slave trade,” and hotly refused to sign, saying he would only play for the New York Yankees. Irabu’s comments, which had been reported in the media, angered some officials and prompted an outburst from one of the MLB executives involved, who told Gene Orza, attorney for the MLBPA, “we have to keep baseball safe for people who look like you and me.” These remarks were conveyed to me and other individuals by Gene Orza, who had been taken aback but, in the interest of maintaining a smooth relationship between the union and management, asked me not to name names. Irabu’s request to be released from the Padres’ claim on him was initially denied by the MLB executive council, but was then approved some weeks later during an appeal after Irabu’s attorneys had threatened litigation. Orza is quoted in The Meaning of Ichiro (Warner Books, NY, 2004) as saying, “If Irabu had had the name of John Smith, with blond hair and blue eyes, I do believe that all this would have never happened.” It might be noted here that in October 2003, a Japanese employee of Major League Baseball’s business arm in New York City sued her bosses for fostering an environment, during her 18-month stint there, in which anti-Asian hostility thrived. In the suit, which was later settled out of court, the plaintiff, Juri Moriooka, claimed that “f—ing Japs” and “nips” were part of her immediate supervisors’ everyday office lexicon.

[2] Asahi Shimbun, October 2, 2004.

[3] The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, by Robert Whiting, Dodd-Mead, New York, 1977, p.200.

[4] “Oh disgraces the Japanese game,” Asahi Shimbun, October 3, 2001.

Said Wakana to the Deiri Supotsu, “Oh would probably say ‘we shouldn’t walk Rhodes.’ But I think we should walk him because I doubt Oh wants to see Rhodes break the record in front of him.” Deiri Supotsu, October 1, 2001.

[5] Deiri Supotsu, May 15, 1980. You Gotta Have Wa, Vintage Departures, New York, 1990, p.158.

[6] Washington Post, Anthony Faiola, November 28, 2006.

[7] Shukan Asahi, August 19, 2005. The article also contained the Hirooka quote.

[8] Ichiko’s practice routine described in Tobita Suishu Senshu, Yakyu Kisha Jidai, Besuboru Magajin, 1960, pp. 30–31. Also see Koryoshi, pp. 799-810, Dai-Ichi Koto Gakko Kishukuryo, September 10, 1930, for summary of Ichiko-YCAC games. Accounts of Ichiko stars appear in Yakyu Nenpo published by Mimatsu Shoten Nai Yakyu Nenpo Henshu-bu, 1912, pp. 309–317 and Undokai #47, April 1912. Kanae Chuman came up with the term yakyu (field ball) for baseball and wrote the first book about it, entitled Yakyu, published by Maekawa Buneido Shuppan in 1897. About Jigoro Kano: According to historical accounts, Jigoro Kano had resurrected the ancient and, at the time, largely forgotten art of jujitsu in the 1870s primarily because he was tired of being beaten up by larger classmates in school. The fighting form he ultimately developed, judo, became a popular sensation in the 1880s after Kano’s judo club met and defeated a jujitsu squad belonging to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police—a squad that included much taller and heavier combatants. This historic encounter (which later inspired Akira Kurosawa’s film Sugata Sanshiro) popularized the idea that a man could defeat a much larger opponent with hard training, fighting spirit and brainpower. The appeal of this concept to the players on the First Higher School of Tokyo squad, of which Kano was an avid fan, and who were trying to beat physically larger American teams, should be obvious. Kano, interestingly, was principal of Ichiko in 1893. See Kano Jigoro, Kodokan. Nunoi Shobo; Kano Jigoro, Zansei Koga, Kaneko Shobo; The Father of Judo, Brian N. Watson, Kodansha International; Kaneko Shobo. Sekai No Denki, Akira Kiribuchi, Gyosei; Kano Jigoro, Nihei Kato. Shoyo Shoin; A History of the Kodokan, University of Montana, www.bstkd.com/judohistory.

[9] From “Yakyu Bushi,” an article appearing in a commemorative work published by the Alumni Association of the First Higher School of Tokyo, February 28, 1903, entitled Yakyu Bushi Fukisoku Dai Ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai.

[10] The Tobita philosophy can be found in the six-volume collected works of the famous coach, entitled Tobita Senshu. See volume 3, pp. 25–28. “Froth coming out of their mouths “ appears in Gakusei Yakyu Ron, Vol. 2, p. 260.

[11] Tokyo Yomiuri Kyojin Gun 50-nen, published by the Yomiuri Group in 1985. See pp. 191–195. The Morinji camp is described in even greater detail in Nihon Yakyu-shi, Showa-hen Sono Ni, by Kyushi Yamato, Besuboru Magajin, Tokyo, 1977, pp. 261–270. It was also described by Osamu Mihara in the book Kyojin gun to tomo ni, Sakuhinsha, 1949, pp. 23–30.

[12] The Fuji-Sankei reporters were Kozo Abe, Shuji Tsunoyama and Osamu Nagatani, who had a combined total of over 100 years covering professional baseball in Japan.

[13] Interview with Motoshi Fujita, Keio University

[14] Japan’s Modern Myths, Carol Gluck, Princeton University, 1985, pp. 180, 185.

[15] “Baseball and the Quest for National Dignity in Meiji Japan,” The American Historical Review, Volume 85, Number 3, June 1980.

[16] Asahi Shimbun, March 11, 2006.

[17] Fusakazu Hayano, PhD. Asahi Kagaku. January 2, 1995.

[18] “Same Sport, Different Structure,” W. Kelly, LOOK Japan, 44 (510 September)

[19] In “Sense and Sensibility at the Ballpark: What Fans Make of Professional Baseball in Modern Japan,” an article about the noisy outfield so popular in Japan, which originally appeared as “An Anthropologist in the Bleachers,” Japan Quarterly, 1997, Kelly declares that, in Japan, in general, the “more numerous infield audience . . . by and large behaves rather like crowds at American ballparks.” This account goes against everything I have encountered in 40 years of watching baseball in Japan, where the contrast between organized cheering groups in the bleachers and the more sedate fans sitting in the infield is clear and is quite different from that found in American parks. To quote one of the many longtime observers who sees the same thing I do, Ichiro Suzuki, a baseball player who spent 9 years in Japan and 5 in the U.S., “ I think Japanese fans, like the Japanese players, suppress their emotions too. They are very otonashii (quiet). You have the cheerleaders blowing trumpets and all. But when they’re not doing anything, the stadium is really quiet. American fans, by contrast, do their own thing—people stand up and dance. The fans get up and express themselves, they show their own individuality, just like the players. You get the feeling they are really enjoying themselves.” Asked why the Japanese fan is so quiet—was it courtesy or shyness?—he responded, “I think it’s shyness. When I’m sitting in the stands in Japan as a fan, I can really understand that feeling.” In “The Blood and Guts of Japanese Professional Baseball” by Professor Kelly (appearing in The Culture of Japan As Seen Through Its Literature, edited by Sepp Linhart and Sabine Fruhstruck, State University of New York Press, June 1998), the professor argues, among other things, that “guts” did not become ideologically central in pro baseball until the V-9 era of Kawakami and the Yomiuri Giants, 1965–1973. This would also be news to the men who participated in the Morinji “vomit camp” as well as to pitchers Motoshi Fujita, who pitched 359 innings for Mizuhara and his Giants in 1959; Tadashi Sugiura, who pitched all four games of the 1959 series against the Giants for the Nankai Hawks, coming off a season in which he won 38 games while pitching 371 innings; and another contemporary, Hiroshi Gondo, a pitcher who threw 429 innings in 1961. These individuals uncomplainingly pitched their arms out for their managers, relying on guts when the inevitable pain from so much wear and tear manifested itself in their elbows and shoulders. Their careers ended early, but as Gondo put it, “The code of bushido was strong. Many times my fingers and arms hurt, but I could not refuse my manager’s request.”

[20] “Learning to Swing: Oh Sadaharu and the Pedagogy and Practice of Japanese Professional Baseball.” In John Singleton (ed.), Learning in Likely Places, pp. 422–458. New York: Cambridge University Press.

[21] See Aku no Kanri Gaku, Tetsuharu Kawakami, Kobunsha, Tokyo, 1980. Tetsuharu Kawakami, President Magazine, “Za Man” series, October 15, 1987. Kyojingun Ni Homurareta Otokotachi, Juntaro Oda. Shinchosha, 2000. Tsuguchi was the number-one draft choice of the Giants but found himself psychologically unable to cope with Kawakami’s strict regimen, as well as memorize the dozens of complicated defensive formations that the manager made his players remember. After being severely rebuked by Kawakami for giving up two home runs in a meaningless intra-squad game played on Fan Appreciation Day in November 1973, during which the Giants celebrated their ninth straight Japan Championship, Yuguchi went into a downward emotional spiral and sought medical treatment. After stays in two different mental hospitals, he died of heart failure in March 1973. Kawakami’s response to the news of Yuguchi’s death was quoted in the above-mentioned Oda book as follows: “The Giants are the ones who suffered. We invested a lot of money, time and emotion in this player.”

[22] “Baseball in Japan: The National Game Beyond National Character” in Baseball in America, pp. 47–52, Washington, DC, National Geographic Society (in conjunction with the National Baseball Hall of Fame).

[23] From the official Central League box score of the game, played on October 24, 1985, at 1 p.m. at Korakuen Stadium.

[24] Author interview with Keith Comstock, Oct 25, 1985. “ . . . those orders came from the front office” was the conclustion of a study done by the editors of Takarajima Magajin-sha, in a special edition entitled “Kyojin gun Tabu Jiken Shi” 1288, December 1, 2005.

[25] Shimoda made his remarks at, among other venues, a meeting of Japan’s professional baseball executive committee, November 14, 1984. The remarks were widely reported at the time by the Japanese media.

[26] From author interviews with Reggie Smith and Ichiro Tanuma of the Yomiuri Giants, who were among those who listened to Shimdoa’s plea, February 12, 1983, Miyazaki. Also author interview with Takezo Shimoda, May 10, 1983. Shimoda’s remarks were also widely disseminated in Japanese press.

[27] Sankei Supotsu, December 5–15, 1980.

[28] The New York Times, September 15, 2001.

[29] Author interview, November 25, 1987. Takeuchi’s remarks were widely publicized.

[30] Author interview with Warren Cromartie, who attended the annual preseason team dinners at which Mutai made his comments. March 15, 1990.

[31] Nagashima’s videotaped remarks were made on March 3, 1999, at a meeting of the SanSanKai (33 Association) in Tokyo.

[32] The New York Times, September 15, 2001.

[33] Nikkan Supotsu, October 2, 2001; Asahi Shimbun, October 2, 2001.

[34] Author interview, October 8, 2002.

[35] I first went to Japan in 1962 with US military intelligence, and I began my lifelong addiction to besuboru, the national sport of Japan. I attended Sophia University there, majoring in Japanese politics, taught English and tended bar on the side to pay my tuition, and then worked for a Japanese firm as the only foreigner in the company. It was there that I learned about 60-hour workweeks, unpaid overtime and ritualistic meetings designed only to foster wa. I discovered the importance of proper form and respect—greeting your boss not by name but by his title, having a ready supply of name cards indicating your rank within the organization, presenting and receiving cards the right way—and the difficulties involved in being the first one to leave at the end of the work day, even if it was well after 6. Nothing I later saw at Time Life or any American company I worked with remotely resembled Japanese counterparts. Sports Illustrated staff worked four days and, except for closing day, everyone went home at 5. At Number, the Japanese equivalent of SI, the midnight lights were always on. I later did film work for the MITI, MOF and companies like Hitachi Metals. That experience revealed more of the same.

I attended, or watched on TV, an estimated 100 games a year. When I got to know the inside of the baseball world in Japan, it was just another version of the Tokyo companies I’d worked for with the long, exhausting hours on the practice field, the constant pregame meetings and post-game hanseikai, and the self-sacrifice required. I cannot recall an American player on a Japanese team I talked to who did not complain about the experience. They might have enjoyed the money and the friendships made with teammates, but not the regimentation of it all and the conflicts that inevitably ensued.

In 1972, I moved to New York, where I drew on my experiences to write my first book, a look at the Japanese culture through baseball, The Chrysanthemum and the Bat. My decision to write such a book was inspired, in part, by my years at Sophia where I studied the Japanese political system and was required to read the works of noted scholars such as Edwin Reischauer, Hugh Patrick and Ruth Benedict. These were all distinguished by pages of intelligent but dense, dry exposition and a total lack of passion. There were no flesh-and-blood human beings and the books conveyed none of the raw energy and emotion that I had experienced in Japan.

I tried to tell people in Manhattan about the factions of the Liberal Democratic Party, the labor unions, the sarariman, but there was zero interest. It was only when I started telling them about baseball in Japan—that there was a magical home run hitter like Sadaharu Oh who honed his skills with a samurai sword, or that there were star pitchers who would pitch three or four days in a row without concern for the obvious potential damage to the arm, or that spring training began in the freezing cold of mid-winter, that people started paying attention. That is what prompted me to write my first book, unprepared though I may have been to do it at the time.

In 1977, after Time named The Chrysanthemum and the Bat the best sports book of the year, I turned down offers to work at AP and McGraw-Hill in order to return to Japan, where I worked for Time Life, then became a sports writer and columnist for a number of Japanese publications, including the Daily Sports and the Shukan Asahi, as well as an occasional contributor to American periodicals like Sports Illustrated. Since 1982, I have divided my time between Japan and wherever it is that my Japanese wife, who works with the UNHCR, is posted, which thus far has meant Geneva twice, Mogadishu, Karachi, Tokyo and Stockholm. I have written 5 books in English; 15 books in Japanese, mostly collections of columns; and a mountain of magazine articles in both languages. I have interviewed hundreds of players and coaches, both Japanese and American (and on both sides of the Pacific) and watched more baseball games than any human being should be required to—so many that I found it necessary to take a break in 1992 and spend 6 years working on a book about organized crime. My best-known book You Gotta Have Wa (1989), a product of 12 years of daily reporting on the Japanese game, is in its 18th printing, and the translated version is a best-seller in Japan. It was chosen as one of the 100 best books of all time by a panel of Japanese literary experts (Hon No Zasshi, 10/1991). Tokyo Underworld (1999) is being made into a movie.

This article was written for Japan Focus. It was posted at Japan Focus on September 29, 2006.

See also Charles W. Hayford, Samurai Baseball vs. Baseball in Japan.