Power Restructuring in North Korea: Annointing Kim Jong Il’s Successor

Ruediger Frank

|

Kim Jong Un (front row, 2nd R), third son of Kim Jong Il, claps during the recent delegates meeting of the Worker’s Party Korea on September 30, 2010. First from left is his aunt Kim Kyong Hui. Photo: Reuters |

“Finally,” one is tempted to say. The years of speculation and half-baked news from dubious sources are over. The leadership issue in North Korea has been officially resolved. Or has it?

The third delegate’s meeting [1] of the Worker’s Party of Korea (WPK) on September 28, 2010 answered a few questions. Still, it left a few unanswered and posed quite a few new ones as well. In the end, Kim Jong Il emerged the undisputed leader. But has his legitimacy become more independent of his father than it used to be? Kim Jong Un has been introduced to the people. Does this mean he is going to succeed Kim Jong Il? Or will he succeed Kim Il Sung? Kim Jong Il’s sister Kim Kyong Hui has been promoted to the rank of General and is part of the party leadership. Is she supposed to support her nephew, or is this part of a strategy to more broadly enhance the family’s power? Her husband Jang Song Thaek is also on board. Will he share the caretaking job with his wife? Are there any other members of the (extended) Kim family on the team?

The Hard Facts

(1) On Monday, September 27, 2010, Kim Jong Un was mentioned for the first time in official North Korean media when he was promoted to the rank of General. Now, at last, we know for sure how to write his name (we use the official North Korean version for English; it would be Kim Jong-ùn according to McCune/Reischauer).

(2) On the same day, Kim Jong Il’s sister was promoted to the same military rank as her nephew.

(3) On September 28, 2010, one day later, the first delegate’s meeting of the WPK in 44 years and the biggest gathering since the last (Sixth) Party congress in 1980 opened after a mysterious delay. It had originally been announced for “early September.”

|

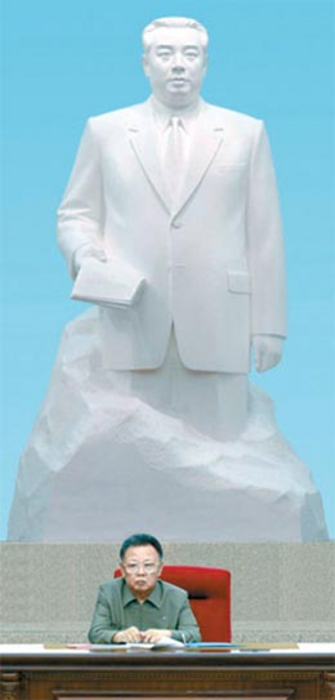

Kim Jong Il in front of a statue of Kim Il Sung at the Worker Party delegate’s meeting on September 28. |

(4) Contrary to western media speculation, Kim Jong Il did not step down nor did he hand over any of his powers to his son. Rather, he was confirmed as the current leader of the party, the military, and the country.

(5) From 1945 until 1980, the WPK had six Party Congresses and two conferences or delegate’s meetings. This means that on average, the WPK had one major Party event every 4.4 years. However, over the next 30 years, it had none. The 21st and so far last plenum of the WPK was held in December 1993. Now, the defunct leadership structure of the WPK has been restored and the delegates elected 124 members of the Central Committee (CC) and 105 alternates. From among the members, 17 were named to the Politburo (PB) of the CC, and 15 as alternates.

(6) The Politburo is headed by a Presidium or Standing Committee of five persons, with Kim Jong Il at the top as the General Secretary of the WPK.[2] It also consists of Kim Yong Nam (82 years old),[3] Choe Yong Rim (80 years old),[4] Jo Myong Rok (82 years old) [5] and Ri Yong Ho (68 years old).[6] The latter was promoted the day before the delegate’s meeting to the post of vice marshal. He ranks above Kim Jong Un and his aunt and is rumored to be a member of the Kim family, which if true, implies a particularly strong base for loyalty. Given the advanced age of most of its members, if the Presidium is not newly elected in a few years, who will remain? This makes Mr. Ri particularly interesting.

(7) All three known close relatives of Kim Jong Il received posts in the WPK. Kim Jong Un became vice chairman of the Central Military Commission (see below). His aunt Kim Kyong Hui became a member of the Politburo and her husband Jang Song Thaek was made an alternate. The names of regular and alternate members were not provided in alphabetical order, indicating a certain hierarchy. Kim Kyong Hui’s name was listed last out of 17 and Jang was 5th out of 15. A day later, he was 14th (out of 15) on a list of short CVs of alternate Politburo members. Kim Kyong Hui was the only member in addition to Kim Jong Il for whom no details were provided.

(8) Except for the Central Committee, there is not a single leadership organ where all three close relatives of Kim Jong Il hold a post; Kim Jong Il does, and holds the top position in each. Kim Jong Un is excluded from the Politburo altogether; Kim Kyong Hui is not on the Central Military Commission; and Jang Song Thaek is only an alternate Politburo member. We could speculate that Kim Jong Il wants to prevent having too high a concentration of power in the hands of one of his relatives. He has made sure that the most crucial instruments of power are staffed with the most loyal of his followers who will be ready to walk the extra mile and fulfill his strategic decisions with all the energy of a family member and co-owner.

(9) As was expected, Kim Jong Un has not (yet) become a member or an alternate member of the Politburo, the second-highest leading organ of the party, but did receive a high-ranking post in the WPK’s Central Military Commission. As far as we know, this is essentially the organization through which the Party controls the military, and hence the most powerful of the WPK’s organs. It is no coincidence that this commission is chaired by Kim Jong Il himself. His son comes next in the hierarchy—he is the first of the commission’s two vice-chairmen. Jang Song Thaek is a member, too, but the one with the lowest rank, so it seems. His name was listed last out of 19. Kim Kyong Hui is not a member of the Central Military Commission.

|

In this undated photo released on Thursday, Sept. 30, 2010, by Korean Central News Agency via Korea News Service, North Korean Leader Kim Jong Il, 2nd from right, poses for a group photo with newly elected members of the central leadership body of the Workers Party of Korea (WPK), including his third son Kim Jong Un, 2nd from left, Vice Marshal Ri Yong Ho, and participants to the WPK conference in front of the Kumsusan Memorial Palace, in Pyongyang, North Korea. Photo: KCNA/AP |

(10) On September 29, 2010, an unusually long and detailed KCNA article was published with profiles of all Politburo members. In addition, a large group picture was published that showed the delegates and the complete Central Committee, including Kim Jong Un. The photo rather openly revealed the true hierarchy within the Party leadership; only 19 people were sitting in the front row, the others were standing. Kim Jong Un sat just one space away from Kim Jong Il, Kim Kyong Hui sat five spaces away from the center. In a KCNA report on the taking of this picture, Kim Jong Un’s name came fourth after the Politburo Presidium members Kim Yong Nam, Choe Yong Rim and Ri Yong Ho. Kim Kyong Hui was number 18, and Jang Song Thaek was number 23 on that exclusive list of 33 leaders.

(11) A total of 14 department directors of the Central Committee were appointed, among them Jang Song Thaek and Kim Kyong Hui. However, contrary to predictions by many analysts, Kim Jong Un does not seem to have been appointed director of the Organization and Guidance Department (OGD), a post his father held before he was announced as Kim Il Sung’s successor.[7] This could be due to a number of reasons. Either, Kim Jong Un already effectively held that post—we may not know since the last time such positions were given officially was 1980—or the division of labor (and power) within the party has changed, for example in the context of the Military First Policy. In that case, the OGD post may simply not be as important as it used to be. This would imply that the Central Military Commission now makes all the important appointments, and the OGD is merely an administrative unit like any human resources department.

(12) The North Korean media published a message from China’s leader Hu Jintao only a day after the delegate’s meeting. He stressed the deep and traditional friendship, close geographical relationship, and wide-ranging common interests of the two countries. Hu pledged to defend and promote the bilateral relationship, “always holding fast to it in a strategic view under the long-term discernment no matter how the international situation may change” (KCNA, 29.09.2010). This was a message to the North Korean people and the international community: China is going to support the new North Korean leadership (model).

What Have We Learned?

The Party meeting provided final proof of what has often been doubted since Kim Jong Il took over as leader of North Korea after 1994. All the other things one might say about him notwithstanding, Kim Il Sung indisputedly was an able politician. He did not choose his eldest son Kim Jong Il as his successor by chance. Despite his health problems, Kim Jong Il is (still) able to play the power game. He paved the way for a new leadership without turning himself into a lame duck. He did so by not leaving any important posts to somebody else—although, at the same time, he did not monopolize those positions. He distributed power among a core group of family members and his father’s loyalists, while also ensuring that none of them can be certain to be significantly higher-ranking than any of their colleagues. As in juche, where in the end everything depends on the judgment of the leader, power in North Korea remains Kim’s sole domain. At the same time, he has done what any good CEO does: delegate authority to avoid energy-consuming micro-management of each and every aspect of his job.

The most important decision regarding human resources has been the introduction of Kim Jong Un as a member of the top leadership of the Party and of the military. He will now have to quickly develop a record (at least on paper) of spectacular achievements, so that he can be quickly presented to the people as the most logical and capable candidate for the next leadership post. Since Kim Jong Un was appointed with a clear reference to the military, Kim Jong Il appears to be following the same strategy his father did after 1980. At that time, North Korea analysts noticed that the late O Jin U, the top military official, was always standing close to Kim Jong Il. It would now be logical to expect that like his father before him, Kim Jong Un will be responsible for the promotion of top military officers, thereby ensuring their loyalty.

|

The military on parade, September 30, 2010 |

In terms of strategic decisions, its seems that the succession from Kim Jong Il to Kim Jong Un will be different from the last changing of the guard in 1994. As early as 2008, it seemed likely that the role of the Party would be strengthened substantially. The restoration of the WPK’s formal power organs and the many biographical details that were provided on the top leadership circle, including the group photo, indicate that the new leader will not be as autocratic as his predecessors. The new leadership will have more faces; we could observe something similar a few months ago in the case of the National Defense Commission. This is the reflection of a trend, not a spontaneous event.

What seems most notable is the renewed emphasis on Kim Il Sung as the sole source of legitimacy in North Korea. Kim Jong Il is not going to replace him, which would have been a precondition for the perpetuation of the current system of leadership. Therefore, in a sense, Kim Jong Un and all those who come after him will be, like Kim Jong Il, successors of Kim Il Sung.

|

Father and son September 30, 2010 |

Concerning the process of power transfer, as expected, a multi-stage approach is unfolding. At least one more stage will be needed. Chances are good that this will take place at the Seventh Party Congress, whose date is as of yet unannounced. 2012 would be a good time considering the health of Kim Jong Il and that year’s auspicious meaning—the 100th anniversary of Kim Il Sung’s birthday. As stated above, Kim Il Sung was a capable politician. He was clearly aware of the fact that sooner or later, his son would face the succession issue. It would be a great surprise if he hadn’t talked about this with him and jointly developed a rough plan as to how create a sustainable model of power succession. The two problems Kim Il Sung could not consider simply for technical reasons were who exactly would show the necessary capabilities to become the next successor, and how much time Kim Jong Il would have to oversee and guide that process.

The year 2008 indeed marked a watershed when, because of his illness, Kim Jong Il realized the need for a quick solution. The last thing an autocrat wants is to create the impression of being forced to act, and of time running out. So he used the already fixed year 2012 not only as the year of the celebration of his father’s 100th birthday, but also as the year when great changes will happen and the gate to becoming a Strong and Prosperous Great Country will be opened. From this perspective, I would argue that Kim Jong Il is indeed fighting a “speed battle,” but in the form of compressing a process that was planned long ago and supposed to last longer, rather than creating such a process from scratch and hastily.

The China Factor

The message of support from Hu Jintao along with the two visits of Kim Jong Il to China before the delegate’s meeting immediately lead to the question: What type of North Korea will China support? Clearly, the last thing China wants is for North Korea to collapse. Such a situation would create a serious dilemma for Beijing. It could either do nothing and watch the U.S. sphere of influence expand right to its border when Korea unifies by integrating the North into South Korea, or it could actively interfere. This would instantly shatter all Chinese efforts to display itself to the carefully watching countries in the region as a peaceful giant that is a real alternative to protection by the United States. In the end, this is what North Korea is all about—competition between Beijing and Washington. Pyongyang knows this.

A third path may be open to China. The North has realized that the economic reforms of 2002, which focused on agriculture and hence closely resembled the Chinese example of 1979, were in principle a good idea, but that conditions were so unlike those in China that the results inevitably differed. In principle, the understanding that economic reform is necessary remains but reservations about the political side effects of such reforms have grown substantially due to the chaos that emerged in the aftermath of the 2002 measures. Given North Korea’s structure as an industrialized economy, reforms need to take place in industry.

There is a well-established blueprint for this; we call it the East Asian model. In short, it consists of a strong state that controls a few big players in the economy—zaibatsu or keiretsu in Japan, chaebol in Korea, and the state owned companies in China. A core requirement for this model to succeed is a huge source of finance, coupled with a strong political partner that, for a while, is willing to turn a blind eye on protectionism. The United States played that role partly for Japan, and very strongly for South Korea. China is now willing to provide this service for North Korea under certain political conditions.

Many signs point in the direction of North Korea “returning” to the path of orthodox socialism, or at least to its East Asian version. “Rule by the Party”—a collective with a first among equals at the top—is not only a key component of any socialist textbook case, it is also characteristic of the Chinese model since 1978. After two leaders of the Mao Zedong type, North Korea may now be getting ready for one similar to the position that the current Chinese President, Hu Jintao, occupies in China—that is, a strong leader who rules as the head of a collective. With some luck, Kim Jong Un might even turn out to be a younger version of Deng Xiaoping—a man who has the power and vision to use this post to initiate and execute crucial reforms.

Ruediger Frank is Professor of East Asian Economy and Society at the University of Vienna and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. He is Deputy Chief Editor of the European Journal of East Asian Studies and a co-editor of The Korea Yearbook, published annually since 2007. This is a slightly revised and expanded version of an article he wrote for 38 North a journal of North Korean affairs. He can be contacted here.

Recommended citation: Ruediger Frank, “Power Restructuring in North Korea: Annointing Kim Jong Il’s Successor,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 42-2-10, October 18, 2010.

Notes

[1] Or conference—not to be mistaken for a congress.

[2] Note that he is not the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Party, as would be standard in other socialist countries. This implies that he stands above the Central Committee, which cannot elect him or vote him out.

[3] Born in Pyongyang, on February 4, 1928. After graduating from “a university,” he worked as a teacher at the Central Party School, then vice department director of the WPK Central Committee, vice-minister of Foreign Affairs, first vice department director, department director and secretary of the WPK Central Committee, vice-premier of the Administration Council and concurrently minister of Foreign Affairs. He has served as president of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly since September of 1998 (source: KCNA, 29.09.2010).

[4] Born on November 20, 1930, in Kyonghung County, North Hamgyong Province. Joined the Korean People’s Army in July 1950. He got the qualifications as an economic engineer after graduating from “a university.” He worked as instructor, section chief, vice department director, first vice department director and department director of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea and chief secretary of the Secretaries Office of the Kumsusan Assembly Hall. Then he held posts of vice-premier of the Administration Council, director of the Central Public Prosecutor’s Office and secretary general of the SPA Presidium. He worked as chief secretary of the Pyongyang City Committee of the WPK until he was appointed as premier of the Cabinet in June 2010 (source: KCNA, 29.09.2010).

[5] Born in Yonsa County, North Hamgyong Province, on July 12, 1928. Joined the Korean People’s Army in December 1950. After graduation from the Aviation School, he worked as battalion commander, regimental commander, divisional commander, chief of staff and commander of the air force of the Korean People’s Army and director of the General Political Bureau of the KPA. He has held the post of first vice chairman of the National Defense Commission of the DPRK since February of 2009 (source: KCNA, 29.09.2010).

[6] Born in Thongchon County, Kangwon Province on October 5, 1942. Joined the Korean People’s Army in August 1959. After graduation from Kim Il Sung Military University he worked as chief of staff of a division, director of the operations department of an army corps, head of a training center, vice-director of the operations department of the General Staff, its deputy chief and head of a training center of the KPA. He has worked as chief of the General Staff of the KPA since February of 2009 (source: KCNA, 29.09.2010).

[7] This department is basically responsible for the Party’s personnel policy and hence regarded as being a key post.