The Korean War, Korean Americans and the Art of Remembering

Ramsay Liem

Abstract

Rarely are personal life stories, art, film, spoken word, and history combined in public exhibition. Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War” (SPP) is an exception. It weaves these elements into a multi-media, interactive experience that lifts the silence shrouding the Korean War, a pivotal event in Korean, United States, and KoreanAmerican history. A public space of memory, the exhibit explores the human experience of the Korean conflict and its hidden but enduring personal and family legacies, and underscores the urgency to end over a half century of national division. For everyone, it evokes reflection about the United States’ role in the war, empathy for survivors, and recognition of our common interest in acting for peace. SPP embodies memories I collected from 3 generations of Korean Americans as part of a unique oral history project. SPP’s conception, design, and implementation are products of an interdisciplinary collective of artists, a filmmaker, a historian, and myself, a psychologist. It is comprised of installation art, interactive art, film, archival photographs, historical markers, and oral history excerpts. SPP is currently on tour most recently showing in Seoul, Korea (link) and Seattle, WA. This article summarizes the aims of the exhibit, the process of creating it, and its reception as a unique experiment in restoring collective memory of the Korean War and reclaiming public voice.

Rarely are personal life stories, art, film, spoken word, and history combined in public exhibition. Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War” weaves these elements into a multi-media, interactive experience that lifts the silence shrouding the Korean War, a pivotal event in Korean, United States, and Korean American history.1 A space to transform private memory into public dialogue, the exhibit explores the human experience of the Korean conflict and its hidden but enduring personal and family legacies, and underscores the urgency to end over a half century of national division. For everyone in this contested global era, it evokes memories of other wars, reflection about the United States’ role in the Korean conflict, empathy for survivors, and recognition of our common interest in acting for peace.

The Korean War (6/25/50-7/27/53) was devastating for Korea and the Korean people. It pitted the United States, South Korea, and 16 other countries against North Korea and China in what the United Nations called a “police action”. A mere three years of fighting resulted in the deaths of 3 million Korean civilians (one tenth of the population), the large proportion in the north, more than a million combat deaths and casualties, the decimation of Korea’s natural and social infrastructure, and national division separating 10 million Koreans from family members, a division that continues to this day.

Koreans Fleeing Pyongyang braving the icy waters of the Taedong River. Photographed: December 10, 1950. Bettmann Collection/CORBIS.

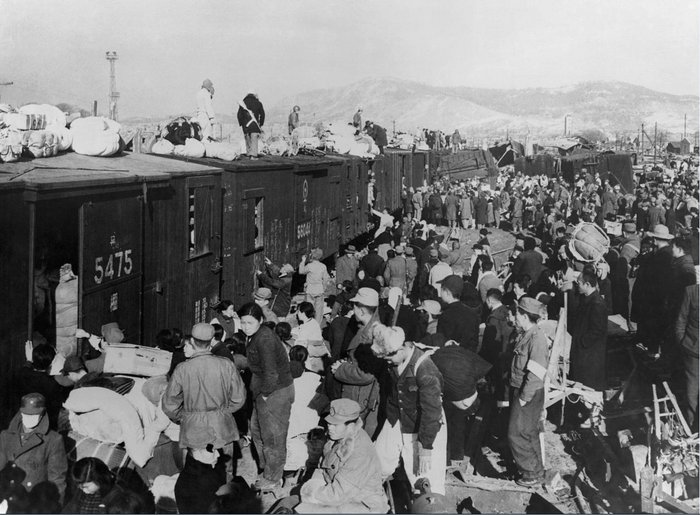

Refugees climbing on trains. Photographed: December 25, 1950, Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

At the conclusion of the fighting, Korea lay in ruins. But the war never ended. It was stalemated in what was supposed to be a temporary armistice agreement. No peace treaty has ever been signed nor has normalization of relations been achieved between the principle antagonists, the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and the United States on one side, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) on the other. The prospects of renewed conflict weigh heavily on Koreans throughout the world.

In spite of the magnitude of losses engendered by this war and the pivotal role it played in shaping U.S. domestic and foreign policy during the ensuing Cold War, most Americans barely recall the Korean “police action.” Ironically, it is at best remembered as the “Forgotten War.”2 But for Korean American survivors and their children, the Korean War remains a source of shared, if not publicly expressed, pain and division. To speak openly about this past is to violate a pervasive popular culture that renders this war “forgotten”, to risk provoking Cold War divisions that linger within Korean American communities, and to expose children and grandchildren to deep personal conflicts that survivors, themselves, may not have reconciled. Hence, the silence surrounding the war is multi-determined. Especially relevant for the Korean American community is the observation of Lisa Lowe who writes that enfranchisement in the U.S. for Asian immigrants requires “forgetting the history of war in Asia and adopting the national historical narrative that disavows the American imperial project…through the denial of history.”3 For Korean Americans Lowe’s comment means acquiescing to the popular remembrance of the Korean War as the “Forgotten War.”

But silence can also be disaffirming and immobilizing. It robs survivors of the opportunity to heal past wounds, denies younger generations of knowledge of their family roots, hinders community reconciliation, and undermines Korean American efforts to call for an end to the stalemated conflict on the Korean peninsula and between the United States and North Korea. These ubiquitous effects of “forgotten” historical trauma have been documented extensively by scholars and activists concerned about other momentous events including the Holocaust and the World War II internment of Japanese Americans.4 Silence about traumatic pasts is also, paradoxically, a medium through which historical trauma is passed from survivors to their children and grandchildren. It constitutes one of the main themes foregrounded in Still Present Pasts.5

The creators of Still Present Pasts shared the belief that a public space of memory and dialogue about the Korean War could challenge these multiple layers of silencing as a means to promote healing, reconciliation, and advocacy for peace. Other work ranging from testimonial art to commemorative museums to memory projects designed specifically for healing and reconciliation served as our precedents.6 We were also urged by many oral history participants, previously unable to convey their experiences to their own children, to share their stories with the younger generation. The exhibit was one means to honour this request.

Still Present Pasts embodies life stories from the Korean American Memories of the Korean War Oral History Project directed by the author.7 Motivated in part by the personal quest of several younger Korean Americans to acquire a deeper understanding of their family’s experiences during the Korean War, the project currently has three-dozen oral histories from three generations of Korean Americans living in the Greater Boston and San Francisco Bay areas. These narratives are among the first public remembrances by Korean Americans of the devastation of this horrific civil and international conflict. They also reveal multiple legacies of the war that influence individual, family, and community life, to this day. These oral histories provide a counterpoint to the invisibility of the Korean War in public consciousness and the U.S. historical record.

The exhibit is the result of two years of collaboration among a group of visual artists, a documentary filmmaker, a historian, and the author.8 Early in our work we made a critical decision to work collectively to conceptualize, design, and implement the exhibit recognizing that our varied professional backgrounds, styles of work, languages of communication – textual, visual, spatial – and perspectives on the Korean War posed difficult challenges to this approach. Yet, precisely because of these differences, it was essential for us to find a common path. We were also aware that our working collectively to design Still Present Pasts violated a deeply held assumption that the arts are intrinsically modes of individual expression.

Each of us first read and listened to the oral history transcripts and audiotapes. We then participated in six months of intense discussions of the oral history material, how particular entries resonated with our own life experiences, and how best to render the richness of what we were learning and experiencing. We ultimately chose the idea of a multi-voiced conversation as the central motif for the exhibit, a dialogue among memories of war survivors mediated by their resonances for us and framed by the historical landscape of the Korean War. The vehicles for conveying this dialogue are print and audio-recorded oral history excerpts, installation and interactive art, spoken word, documentary film, archival photographs, and historical text.

A Brief Synopsis

The narrative framework for Still Present Pasts draws visitors into silenced memories of the fighting and its immediate aftermath, legacies of the war harbored by Korean Americans, and prospects and hopes for reconciliation. The entire exhibit can be viewed on-line at www.stillpresentpasts.org.

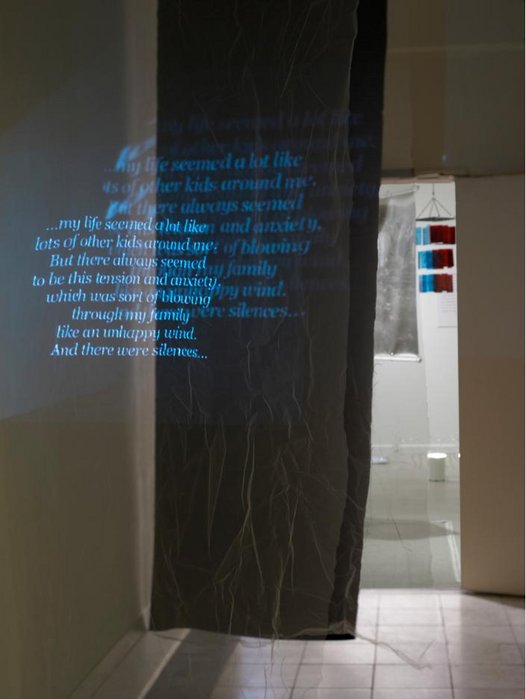

As visitors enter the exhibit, they hear the voice of war survivor Suntae Chun: “… When the war broke out, I was member of my school’s swimming team…we just enjoyed swimming around that lake until dark…then about 10:00 in the morning, a bullet dropped into the lake…” In the midst of the war’s chaos, evacuations, and bombings, millions of family members were separated from one another. In desperation, people wrote frantic messages wherever they could – on fences, sides of trains, houses – seeking lost relatives. Here, the foreboding in Mr. Chun’s recollection leads to a contrasting site that features words from a second generation interviewee, projected through two layers of sheer cloth onto an opaque third: “…my life seemed a lot like lots of other kids around me. But there always seemed to be this tension and anxiety, which was sort of blowing through my family like an unhappy wind. And there were silences…”

Silences. J-Young Yoo, cloth, projection, 124″ x 108″ x 36″ 2004. The projected excerpt in this piece is by Orson Moon.

Entering the exhibit at this installation, visitors are introduced to the problem of silence surrounding the Korean War and invited to break it by serving as witness to the memories embodied in subsequent exhibit works.

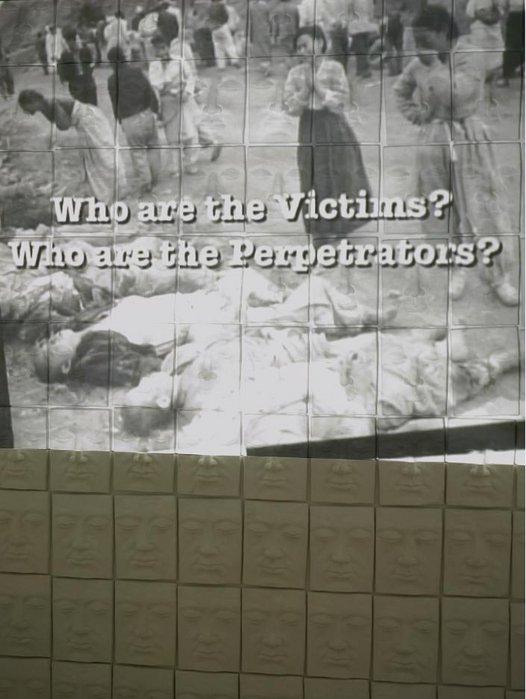

Visitors then encounter multi-media and interactive works of art interwoven with personal stories, photographs, and historical text. One of the pieces is a multi-media work (by Ji-Young Yoo), a projection of digitized archival footage of American soldiers and civilians onto a screen of 100 shallow relief faces.

Ji-Young Yoo, video, video projector, clay, 82″ x 62″, 2005.

Close-up of shallow relief face.

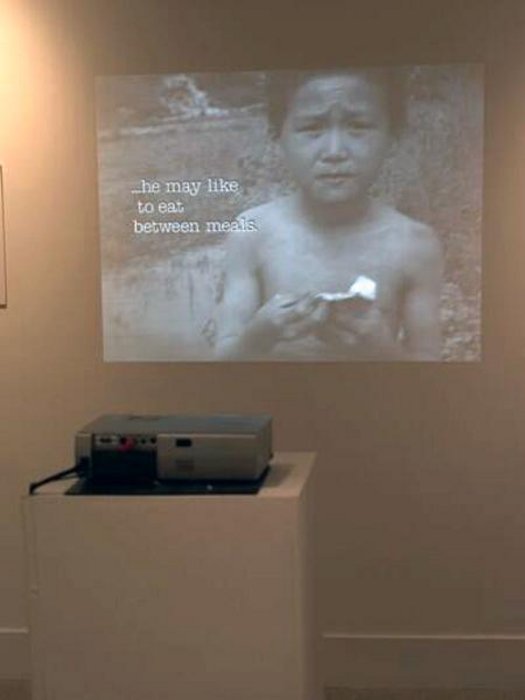

This piece speaks of the victimization not only of Korean civilians, but also Korean, Chinese, United States, and United Nations soldiers, many of whom were young recruits with little knowledge of Korea or their purpose in being sent to fight in the Korean War theatre. Audiences also watch “Practical Hints about Your Foreign Child” (by Deann Borshay Liem), a short documentary questioning the use of American consumer goods, chocolate and chewing gum, to salve the trauma of orphaned children, the first of the tens of thousands of Korean adoptees whose dispersal to the west began during the Korean War.

Practical Hints about Your Foreign Child. Deann Borshay Liem, video 51″ x 39″, 2005.

“Girl with a Tank” (by Injoo Whang) reflects paradoxes of war found in memories of women survivors, unexpected opportunities for growth and adventure created by the breakdown of patriarchal social relations as part of the ruins of war.

Girl with a Tank. Injoo Whang, cloth, thread, Sumi ink, ink, 90″ x 27,” 2005.

This work was created by painting an iconic image on cloth of a girl standing in front of a large U.S. tank, dismembering it, and then reconstituting the fragments into a stunning tapestry portending new possibilities that can be born, even during wartime. Accompanying this piece are several oral history excerpts that convey the paradox of war. For example, “During the war the traditional family structure broke down and people like my mother had more freedom…she went all over the place. She followed her older brother around, older boys, and learned to swim.”

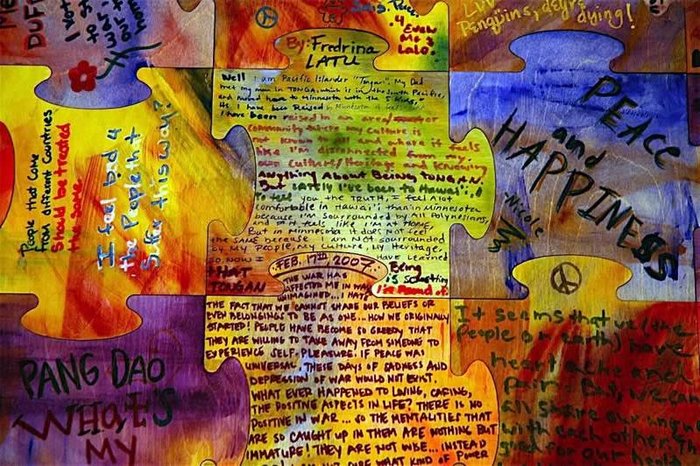

An installation in the medium of a puzzle (by Yul-san Liem) examines the quest, often of younger people, to fill in gaps in family history tied to the war years.

Our Puzzle. Yul-san Liem and exhibit participants, wood, watercolor, cloth, ink 84″ x 108″, 2004.

A portrait of an extended family intermingled with the excerpt, “…when I first heard these stories a lot of things fell into place, and it felt as if a weight had been lifted from me” centers on a giant puzzle that visitors are invited to assemble – to fill in the holes. Additional blank pieces are provided on which viewers can place their own comments, memories, or images and add them to an ever-expanding mosaic of recovered memory.9

Contributed puzzle pieces.

This interactive installation is one means to begin constructing a collective memory of the Korean War.

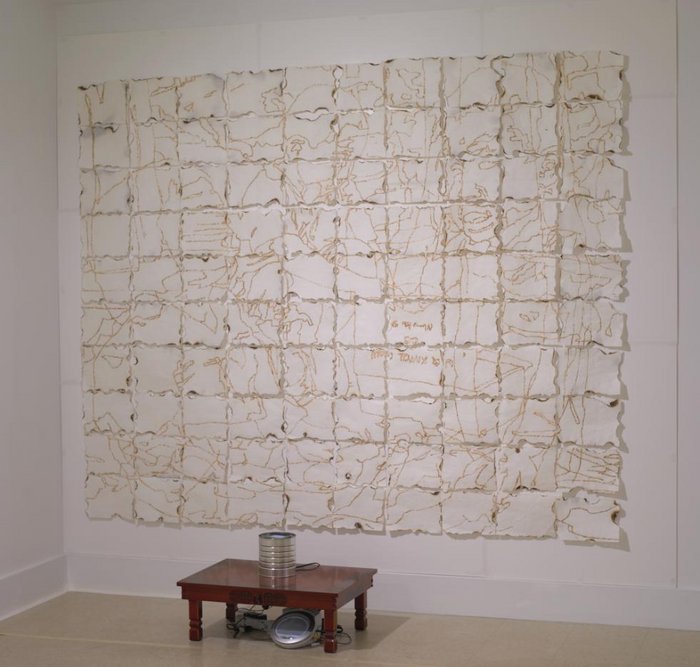

Hunger and starvation dominate survivors’ memories of the war. For artist Ji-Young Yoo, one particular recollection of peoples’ desperation was especially poignant – the common practice of refugees lining up at the end of the day to purchase a bucket of garbage from GI mess halls. Her piece entitled “Boodaechigae” is comprised of a large mural depicting the image of starving children burned with a hot iron in 100 pieces of rice paper.

Boodaechigae. Ji-Young Yoo, video, Korean rice paper, Korean table, C-ration cans, video monitor 82″ x 99″ 2005.

In front of the picture is a large GI ration can placed on top of a traditional Korean table and containing a small monitor with a video clip of the artist making a contemporary Korean stew, boodaechigae. (boodaechigae translated literally as “battalion stew.”) Boodaechigae is a very popular dish in Korean and Korean American restaurants today and is a hodge podge of spam, hot dog bits, and various vegetables. Most younger Korean Americans have no idea that this dish is a legacy of the Korean War when starving refugees survived with the “hodge podge” of GI garbage. Exhibit visitors also hear the voices of oral history participants talking about eating that garbage. One man says, “That’s good food, very tasty! But you know, that situation is very sad.”

The journey through memory and legacy leads to the “Bridge of Return” (by Yul-san Liem).

Bridge of Return. Yul-san Liem and exhibit participants. Co-design and construction: Evan Crane and Dick Galyon. Wood, cloth, stone, ink, 159” x 52” x 74”, 2005.

The name references a real bridge, the Bridge of No Return (italics added) that repatriating POWs from the north and south crossed at the end of the war never to be able to return because the division of the Korean peninsula became permanent. Liem’s ten-foot long bridge unites contemporary visual themes with symbolism from traditional Korean shamanism in an experiential, participatory installation. Audiences simultaneously travel over the bridge and between the white cloth of the Shaman’s pathway that intersects the human and spirit worlds. Those who cross the bridge are invited to leave messages of personal, community, or national wounds and divisions beneath it.

Exhibit visitor writes a message.

In doing so, they symbolically cross the DMZ (the site of Korea’s national division) and overcome pain from their own and others’ histories, imagining national and personal reconciliation with their bodies.10

Throughout the exhibit the voices of war survivors and their families emerge to speak back to the artists and audiences in the form of audio and video recording and enlarged written text. Historical placards marking time according to the pre-war and war years, the armistice signing, and the post war years in turn anchor these elements.

Still Present Pasts also includes the performance art piece, “6.25; history beneath the skin” (by Hyun Lee, Grace M. Cho and Hosu Kim and staged by Carolina McNeely). In a striking collage of personal testimony, audio recording, body movement, and slide and video projection, each woman breaks the silence surrounding her own Korean War legacy and offers insights into the on-going impact of this tragedy.

6.25; History Beneath the Skin. A performance art piece by Grace M. Cho, Hosu Kim, and Hyun Lee. Stage Director: Carolina McNeely.

The stories of the three performers are woven together by a thread of oral history voices that speak of bombings, deaths, evacuations, struggle, survival and eventual immigration to the U.S. Performed live, a video recording of “6.25” is also installed in the exhibit with other pieces embodying the myriad of legacies that connect contemporary life to a past of war.

Wellesley Gallery.tif Jewett Art Center, Wellesley College.

Response to Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War”

On national tour since its opening in 2005,11 Still Present Pasts has attracted unexpectedly large and welcoming audiences overcoming our initial uncertainty about how Korean Americans would receive this invitation to revisit a suppressed past. Visitors have come alone, in groups, and as families, many on more than one occasion. Judging from their spontaneous comments and written messages, the art and oral history voices resonate deeply with many. Some visitors also express ambivalence toward the exhibit moving toward and away from it, literally circling it, before finally entering. Nonetheless, the resonance people experience with the memories embodied in the art is often powerful. A young person said, “It causes me to see my family in a different light…I wonder how painful it was for my (deceased) grandma … I wish I had asked before it was too late.” Another visitor commented, “ I wish I were in Boston so that I could revisit the galleries and just inhabit that space for a long, long time.” A person not of Korean descent said, “This was my generation’s war. I’m embarrassed to say I had almost forgotten it. I learned so much.” She like many others from diverse communities had little difficulty identifying with the exhibit themes and voices – the difficulty speaking about traumatic histories, the tragedy of divided families and communities, the longing for healing and reconciliation. Many from immigrant communities saw the past and ongoing conflicts in their homelands mirrored in the memories of Korean Americans.

Thus far, the clearest indication that Still Present Pasts facilitates dialogue within families is the positive response of audiences to special programs that often accompany the exhibit, for example “Intergenerational Dialogue about the Korean War”. Organized as a panel discussion followed by breakout groups, this program has attracted broad interest and fostered indirect, if not always direct, conversations among family members about the war. Judging by the remarks of attendees, it is often easier to ask someone else’s parent or grandparent about their experiences of the war than one’s own, or for elders to disclose memories to a group of young people and, thereby, indirectly to one’s own children or grandchildren. As first attempts to break families’ silences, these gatherings have been well attended and deeply engaged.

The broad Korean American ethnic media coverage of the exhibit is an indication that Still Present Pasts has also begun to penetrate community silences about the Korean War. Generally cautious in their approach to sensitive topics like the war, all of the major print, radio, and television media in the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, reported on the exhibit when it showed in Oakland. Ranging from neutral, descriptive pieces to strong endorsements urging community attendance, this response to Still Present Pasts represents the first time the full spectrum of the Korean American media has broached the topic of the Korean War. By itself this lifting of community self-censorship does not resolve Cold War divisions that remain in the community, but it marks a significant step toward ending the taboo surrounding talk about the war to which many Korean Americans have been subjected.

Following the opening of Still Present Pasts in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one oral history participant whose war experiences are included in the exhibit, Min Yong Lee, made this comment: “Now I feel really good. Now I can say I am from a separated family. Now I am free, now I have an identity.” Like many others, Mr. Lee had lived in the shadow of Cold War ideological suspicions for over a half century having come from a family where some relatives “went to the communist north” during the war. To survive in the south and the United States, he hid his past, even from his own daughters, suppressing his personal history and identity. Seeing his story as part of the collective history of Korean war survivors and experiencing the positive reception of the exhibit by the community, he began to reclaim his voice and family history.

Others have expressed similar sentiments, although in some cases with the caveat that they wished the exhibit were a permanent collection. One man explained this reaction by saying, “Inside here, we are safe. When we leave, we still have to watch behind us.” His comment suggests that memory and voice are liberated within this artful space of remembering but that silence still remains serviceable on the outside. His response reflects both the efficacy and the limitations of Still Present Pasts in the current period.12

The Art of Remembering

The ability of Still Present Pasts to vividly bring to life long suppressed memories of war and to convey their moral urgency in the present is the result of a unique dialogue fostered between oral history interviewees and our artists. The art works embody oral history memories as they resonated with each artist’s life history and aesthetic, resulting in pieces that are truly co-productions. Furthermore, each piece conveys cognitive and sensory aspects of memory mirroring a natural process of remembering that draws upon semantic, visual, emotional, and auditory traces.13 The exhibit thus speaks to visitors on many levels including the rational and the emotional immersing them in recollections of a wartime past and its active legacies in the present.

At the same time, the exhibit works are not didactic. Rather than insist on a particular reading of war memories they evoke personal recollections and experiences that each observer brings to his or her viewing. For Korean Americans these are often their own unspoken memories of the Korean War while for visitors who are not Korean, remembrances of other catastrophic events become infused with personal meaning. In all cases Still Present Pasts serves as a catalyst for recalling experiences, often traumatic, that fall outside the realm of everyday conscious reflection and talk. In this respect the exhibit works bear a resemblance to testimonial art, which “is disruptive and demanding…In its moments of testimony, art invites us to trip against elements that had seemed to lie beyond recollection, outside familiar patterns or designs of remembrance, generating a motion between prevailing narratives and their oversights.”14 In their conception they also reflect “a kind of cultural work about …trauma and loss that speaks to and gives a visual language for the experiences of those who are unable to ‘move on,’ to reconcile or forget the past, and to those that remember and live with the effects of violence…”15

Still Present Pasts is also more than an artful chronicling of a troubled past intended to evoke empathy and recognition in it audiences. As discussed by one of our performance artists, Grace Cho, “by bringing traces of the past to bear on the present, ‘breaking silence’ then is not a final resolution of guilt, but an implication of the audience in a greater entanglement with trauma. This intimacy between artists and audience members diffuses the pain carried by war survivors at the same time that it heightens a shared sense of responsibility for the injury. It is as if we are releasing ghosts not for the purpose of laying them to rest, but to renew their agency and enchant the world with spirits.”16 Because the Korean War is both technically and legally unended – it was stalemated in a now 55-year-long armistice agreement – the trauma of the war is not over; it remains a remnant of the past that is literally ‘still present.’ As many have said, war on the peninsula and with the United States could reignite at any time and almost did in 1994 when U.S. – North Korea nuclear disarmament negotiations reached a contentious impasse.17 Failure to conclude the war with a peace treaty also serves as a major impediment to resolving the current U.S.-D.P.R.K. conflict over North Korea’s nuclear program. Mired in years of mutual hostility, the unended Korean War has brought us once again to the brink of catastrophe. Thus, Still Present Pasts aims not only to uncover a forgotten past through the artful embodiment of oral history voices, but to evoke the “shared sense of responsibility” that Cho references to end the last vestige of the Cold War.

Breaking Silences

More than anything else, Still Present Pasts is about claiming voice, breaking six decades of silence about how ordinary people experienced the Korean War in Korea and the United States. The people whose oral histories inspired our exhibit challenged the culture of silence in the U.S. that shrouds the Korean War, risked becoming targets of political and ideological conflict in their own communities, and were willing to relive personal traumas and expose them to other family members as well as strangers.18 For many of these people the interview was the first time they spoke openly about their war pasts and the ghosts that continue to haunt them. By permitting us to include some of their memories in a dialogue with the exhibit artists, they stepped further into the public arena. They also joined others whose public testimony has been a force for resisting and redressing social and political injustices, for example, Holocaust survivors, Japanese American internees, Argentinean mothers of the disappeared, victims of Cambodia’s Killing Fields, and the thousands of human rights survivors worldwide who have testified before national and international truth and reconciliation commissions. Without their contributions, Still Present Pasts could not have begun a process of lifting the silence about a tragic, unresolved chapter in American history that continues to reverberate in the present.

This article is a revised version of “War and the Art of Remembering: Korean Americans and the Forgotten War,” The International Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences Vol 3 2008.

For the entire Still Present Pasts exhibit online, see this link.

Ramsay Liem is a professor of psychology at Boston College and co-coordinator of the Asian American Studies concentration. His interests include the intergenerational transmission of sociohistorical trauma, human rights and mental health, and Asian American Studies. He also has longstanding interests in post war U.S./Korean relations. He is the project director for Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War.” With Deann Borshay Liem, he is producing a documentary film, “Memory of Forgotten War” featuring Korean War survivors. (A sample reel can be viewed here) He is the author of “Silencing historical trauma: The politics and psychology of memory and voice,” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 13(2), 153-174, 2007.

Recommended citation: Ramsay Liem, “The Korean War, Korean Americans and the Art of Remembering,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 41-4-09, October 12, 2009.

Notes

1. Belying the hotly contested nature of this conflict, the “Korean War” is variously referred to by some in the United States as the U.S.-Korean War, by the United Nations as the Korea “Police Action,” by the Republic of Korea (South Korea) as the “6.25” war, by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) as the “Fatherland Liberation War,” and by the People’s Republic of China as the “War to Resist American and Aid North Korea.” The term “Korean War” is used throughout this article.

2. See C. Blair, The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-1953. New York: Times Books, 1987; S. Levine, Some Reflections on the Korean War. In P. West & J. Suh (Eds.), Remembering the Forgotten War: The Korean War through Literature and Art (pp. 3-11). Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2001.

3. L. Lowe, Immigrant Acts. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996, p. 27. Similarly, with reference to World War II, T. Fujitani, G. White, & L. Yoneyama coin the term “perilous memories” as recollections of marginalized survivors that “could subvert dominant historical readings (i.e. master narratives)…of the major warring powers.” These memories must be suppressed or silenced to preserve official accounts of the past. Perilous Memories: The Asia-Pacific War(s). Durham, NC: Duke University Press, pp. 2-3. See also D. Nagata, Legacy of Injustice. New York: Plenum Press, 1993 for the effects of silenced trauma on the attitudes and willingness to speak out against racial injustice of the children of Japanese American WWII internees. In the late 1970s these internees began to testify to their incarcerations and precipitated a broad redress and reparations movement culminating in the Japanese Redress Act (HR 442) in 1988. Referencing Asian Americans more generally.

4. See Y. Danieli (Ed.) International Handbook of the Multigenerational Legacies of Trauma. New York: Plenum Press, 1998 for an excellent collection of writings about the implications of silence for the children of trauma survivors.

5. For a lengthier discussion of multiple factors colluding to silence talk about the Korean War, see R. Liem, Silencing Historical Trauma: The Politics and Psychology of Memory and Voice, Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 13(2), 2007, 153-174.

6. For further discussion of art as testimony, see K. MacLear, Beclouded Visions: Hiroshima-Nagasaki and the Art of Witness. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1999. The Healing Through Remembering Project designed to foster reconciliation between conflicted parties in Northern Ireland shares many of the objectives and elements with the Still Present Past exhibit. See R. McClelland, The Report of the Healing through Remembering Project, June 2002.

7. For more discussion of the Korean War oral history project, see R. Liem History, Trauma and Identity: The Legacy of the Korean War for Korean Americans, Amerasia Journal, 29, 2003-2004, 111-129 and R. Liem, “So I’ve Gone Around in Circles…”: Living the Korean War, Amerasia Journal, 31, 2005, 157-178.

8. The exhibit collective includes artists Yul-san Liem, Injoo Whang, and Ji-Young Yoo, documentary filmmaker Deann Borshay Liem, historian Ji-Yeon Yuh, language consultant, Seung-Hee Jeon, web designer/technical consultant, Young Sul, and project director, Ramsay Liem. Other participants include spoken-word artists Grace M. Cho, Hosu Kim, and Hyun Lee and their artistic director, Carolina McNeely, and contributing artists Erica Cho, Sukjong Hong, and Yong Soon Min. Wol-san Liem prepared a study guide for high school teachers and students.

9. Two examples from text written by visitors on hundreds of puzzle pieces are:

“My father told me a story. He used to steal apples and eat them at night knowing there could be worms in them. That’s how he got his protein. This is a post-war story but it tells me the hunger lasted for a long time even after the war.”

“For those of the United States who caused the trauma, I apologize.” (U.S. Korean War Veteran)

10. One example of a message left by visitors is:

“I need to heal myself from my fragmented/wounded self. I need to get beyond:

Abandonment

Adoption

Abandonment again,

And abandoned again.”

More than 120,000 children from Korea have been adopted in the U.S. since the Korean War.

11. Still Present Pasts premiered on January 29, 2005 at the Cambridge Multicultural Arts Center in Cambridge, MA. Since then it has shown at Wellesley College, the Queens Museum of Art in the Bronx, Pro Arts in Oakland, CA, LA Artcore in Los Angeles, and Intermedia Arts in Minneapolis. The exhibit also appeared at the Total Museum of Contemporary Art in Seoul, Korea and opened at the Wing Luke Asian Museum in Seattle, WA, December 13, 2008. For more information, see this link. For an exhibit catalogue or to inquire about bringing the exhibit to your university or community, contact the author at [email protected].

12. For sample coverage of Still Present Pasts, see R. Kim, “The Past in the Present.” Koream 17:3 (2006) 32-34; M. Abbe, “An Unresolved War.” Star Tribune 27 April 2007; B. Payton, “Artists Remember the ‘Forgotten War’.” Oakland Tribune 3 March 3 2006: Metro Section 1, 4.

13. Psychological research on cognition and memory demonstrates that the encoding of experiences associated with high arousal and strong negative emotions implicates regions of the brain responsible for sensory processing rather than higher order conceptual processing. (See E. Kensinger & D. Schacter, Remembering the Specific Visual Details of Presented Objects: Neuroimaging Evidence for the Effects of Emotion, Neuropsychologia, 62, 2007, 2951-2962.) Exhibit elements that evoke intense, negative emotion are, therefore, likely to be especially effective in stimulating recall of events that bear a resemblance to these artful images.

14. See K. MacLear, ibid, pp. 187-188.

15. This quote from M. Gómez-Barris references the cultural politics of Chilean artist Guillermo Nuñez’s art and testimony, which the author analyses in light of the persistence of traumatic memory. See M. Gómez-Barris, Chile’s Tortured Legacies: Guillermo Nunez’s Art Practice, p. 2. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Montreal Convention Center, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 2006.

16. See G. Cho, Performing an Ethics of Entanglement in Still Present Pasts: Korean Americans and the “Forgotten War,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory, 16, 2006, 303-317, p. 315.

17. See B. Cumings, North Korea: Another Country. New York: The New Press, 2004.

18. The Still Present Pasts collective expresses its gratitude to the oral history participants for sharing their life stories and for their willingness to help create the exhibit. We thank: Soam Chang, Suntae Chun, Helen KyungSook Daniels, Eungie Joo, Helen Sunhee Kim, Kyung Hui Lee, Min Yong Lee, Orson Moon, Andrew Park, Kee Park, Song J. Park, and Won Yop Kim.