Compiled and introduced by Philip Seaton

“Many people asked me what happened to me in

My Marine company was going through a village, when we were attacked by some [North] Vietnamese soldiers. Many Marines were killed and many were wounded. The rest of us just ran around, trying to find a place of safety. I ran behind a Vietnamese house and ran down into their family bunker. …

Once I got down inside of this bunker, I realized that there was someone there with me. I turned and looked. It was a young Vietnamese girl, maybe 15 or 16 years old. … She looked at me like I was a monster. She was very afraid of me, but for some reason she would not get up and run away.

She was breathing very hard, and she was in great pain. So I crawled over to her and realized she was naked from the waist down. I could not understand what was wrong with her. She kept breathing hard, and she kept making pushing sounds. I looked between her legs and saw the little head of a baby. …” – Allen

I. Introduction

When a second-year undergraduate at

Allen Nelson’s engaging talk covered his reasons for joining the Marines, military training, life in Okinawa before heading to Vietnam, his experiences in the Vietnam War, and his struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after returning to the US. The talk was translated by journalist and

The evening had touched on so many aspects of war and peace activism in contemporary

This paper, therefore, is a collective effort. It provides not only a portrait of Japanese grassroots and student peace activism, but also reveals the complex linkage between diverse topics in Japanese discourses of international conflict.

Philip Seaton,

II. Allen Nelson’s Talk – Adapted from To End the Misery of War

Allen Nelson joined the Marines after dropping out of high school. He served one tour of duty in

His frequent visits to

Before starting his talk at Hokudai, Nelson sang Amazing Grace. The talk itself followed closely the text of one of his publications. This section presents an abridged version of Nelson’s story through excerpts from his book To End the Misery of War Forever.

Allen Nelson sings Amazing Grace. In the background are Chika and Shimpei.

Nelson started by describing what drove him to join the Marines.

“I know that you do have poor areas in

About his military training, Nelson stressed the emphasis on learning to kill:

“[I]n training you do not learn anything about keeping peace; you only learn how to kill. … There were forty young men in my platoon, all 18-year-olds or 19. My drill instructor would stand in front of us and he would say, “What do you want to do?” And we would yell, “Kill.” And he would say, “I can’t hear you!” And then we would yell louder, “Kill!” And then he would say, “I still can’t hear you.” And then we would all scream at the top of our voices, “Kill!” and then we would roar like lions.”

After basic training, Nelson was transferred to

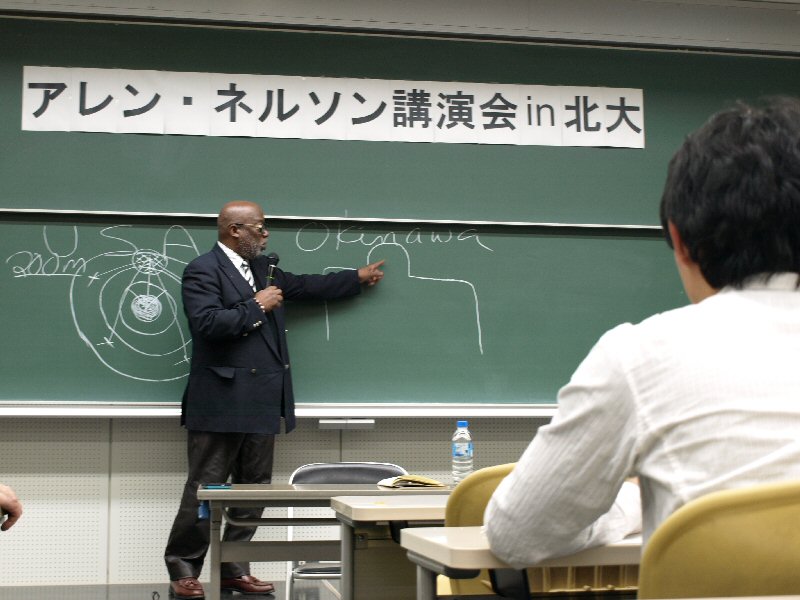

Allen Nelson explains about using bulls’-eye targets in

Nelson then illustrated why he favors the complete removal of American bases from

“[After training, we] would go into town to do three things: to drink, to fight and to look for women. Many times we would get drunk and take taxicabs back to the gate of the camp. We would get out of the cabs, and then refuse to pay the cab drivers. If the cab drivers insisted upon being paid, they would be beaten; some were beaten unconscious. When we visited the women and after they delivered their services, many times we would refuse to pay them also. If the women insisted on being paid, they would get the same treatment as the cab drivers received; they would be beaten. Many people seem surprised at this behavior. But you have to remember that we are Marines and soldiers. We are trained to be violent. When we come to town, we don’t leave our violence on military bases. We bring our violence into your towns with us.”

His recollections of his 13 months in

“I killed many Vietnamese soldiers and I saw many people die. The first thing that I learned in the jungles of

Nelson described the indiscriminate nature of the

“When we attacked the villages in

But perhaps the most arresting part of Nelson’s description of battle was about the smell:

“The smell of rotten bodies is so powerful that it will make your food jump from your stomach to your throat. It will make your eyes water, your nose run, and your whole body weak. This is the smell that I will never forget because this is the smell of war. … If they could make movies that could give you the smell of war, you would never go to the movie theaters to see war movies.”

Nelson described how he suffered from PTSD on his return from

“I did not tell them what I did or what I saw in the jungles of

Now able to speak out, Nelson calls the

In 2005, Nelson’s speaking activities came full circle when he went back to

“I was able to speak to a crowd of two thousand Vietnamese people gathered in Danang and I did something that I had long wanted to do: to tell the Vietnamese people of my crimes against them and offer my deepest apology and sympathy. I apologized to them for burning their villages, killing their children and torturing elderly people. … The first step toward reconciliation is justice. Justice can only be served if nations are honest about the crimes committed in the past. It’s not enough to say you’re sorry; you have to list each thing the country has done to the other country, each village that was burned and each person that was killed.”

Nelson finished his talk with this message: “Peace starts right here in this hall, on your campus, in your homes and with each and every one of you.”

Kageyama Asako

Kageyama Asako

Nelson’s talk was followed by a short presentation by Kageyama Asako, a

I contacted Kageyama after the meeting and she sent me a copy of Fujimoto’s previous documentary film, Marines Go Home (2006), which she had narrated. [5] Marines Go Home documents local anti-base activism in Yausubetsu (

Publicity Poster for Marines Go Home

Locations of Yausubetsu, Henoko and Maehyang-ri

Marines Go Home provides the critical link between the key contributors to this paper: the Japanese SDF’s practice range in Yausubetsu. Allen Nelson started coming to

III. Reaction to Nelson’s Talk

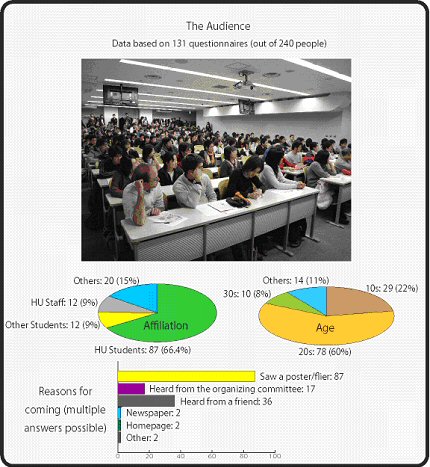

As the photo below indicates, Nelson’s talk had been “standing room only.” According to main organizer Chika, the audience had exceeded expectations. People were asked to fill in a questionnaire about Nelson’s talk. Of the about 240 people who attended, 131 returned the questionnaire. The high return rate was indicative of the interest generated by the talk.

The basic findings of the audience questionnaire – their affiliations (most were

The questionnaires also asked for people’s impressions of the talk. Many people commented that it was good to hear first hand the experiences of someone who had been to war, and that the talk made them think about what they could do as individuals. The organizing committee selected the following comments from the questionnaires.

“The phrase ‘We were trained to be violent’ was very striking. It’s so sad that people in the military are educated to be completely vicious, and lose things which should be normal for people: dignity, reason and emotion.” (Student, 20s)

“Before I only thought of war as something you see in films. Allen’s comment that there’s no smell in movies was particularly arresting for me. I can’t imagine the smell of war. Most people can’t grasp what real war is like. By telling us of his terrible experiences, I think people could understand more about war.” (Student, teens)

“I hadn’t thought about Article Nine seriously up until now. But now I realize I have Article Nine to thank for the lack of war in my life up to now. I want to work to preserve our constitution.” (Student, teens)

“Who is bad, what is bad, and why does war happen? We must look inside ourselves for the answers. The worst thing is for us to be indifferent to war. I want to think carefully about what I can do in the future and do something active to promote peace.” (Student, 20s)

However, while most comments were positive, some people made criticisms.

“He could have talked more about the period when he lived on the streets and the war’s psychological effects (PTSD). This would have illustrated the devastating effects of war on a soldier’s mind, or the absurdity of a society that sends people to war and then forgets about them. I also wanted more detail of life in

This French student was skeptical about some of the comments Nelson made about

One contentious statement was that, as in the

On the issue of the “occupation” of Japan by the US, we concluded that this is an interpretation one is much more likely find in communities living with American bases (particularly in Okinawa, where land was requisitioned for bases). Furthermore, this rhetoric is indeed used by the Japanese anti-base movement. In parts of Japan far from bases, there is much less consciousness of being “occupied,” but Nelson’s point is that Japan is “occupied” because it does not have the ability to insist on the removal of the bases.

The overall response to Nelson’s talk was positive, and it served to strengthen a variety of “pacifist” sentiments in a number of the audience. The comments typified the findings of Mari Yamamoto’s research into grassroots pacifism in Japan, which suggest that Japanese sentiments of heiwashugi are often devoid of strong ideological roots, oscillate between pacifism (a moral objection to all war) and pacificism (placing political limitations on the ability to conduct war), and are best described in English as a well-meaning anti-war stance or “popular pacifism”. [8] Nelson’s ability to elicit this kind of reaction is testimony to his engaging personality (which was also very evident during our follow-up interview), and his ability to tap the sometimes latent peace sentiment widely shared among many Japanese.

IV. The Organizing Committee – Insights into Student Peace Activism

Following Nelson’s talk, the organizing committee met on a number of occasions in my office to prepare this article. This section analyzes their motivations for organizing Nelson’s talk and their broader activism. Background to the talk is provided by the following “interview” with principal organizer, Chika. [9] The more we discussed the issues, the more the diverse reasons for all four members’ activism emerged.

The organizing committee meets. From left to right – Yasunori, Shimpei, Udai and Chika.

Chika, tell me about why you invited Allen Nelson to speak at Hokudai.

I first met Allen briefly in early August 2007, just before attending the “2007 World Conference against A & H Bombs.” [10] I arrived back in

Why did you want to go to Yausubetsu?

I went mainly because my friend Yamamoto Koichi invited me! He is one of the people who support Allen’s speaking tours in

Photo of Heiwa Bon-odori

What were your first impressions of Allen?

We got talking about insects. I am afraid of insects. Allen said he was, too, and that he could not bear all the insects in

How did you go about organizing the lecture?

I first spoke to Udai and Shimpei, who had also been in Yausubetsu. We formed a committee and contacted the people who organize Allen’s schedule in

Shimpei (right) with Nelson in Yausubetsu, August 2007.

How did you publicize the event?

We handed out fliers and put up posters around campus, but I put most effort into word of mouth. It helped that Allen would be speaking in English because I could ask exchange students along, too. We also had to convey why it was important for Allen to be speaking to us. Allen would be talking about his experiences in

Looking back, what were your impressions of the event?

I think reaction to the talk was very positive. At the moment it is not that easy to tell people around Hokudai that you are active in the peace movement. Some people are not keen to publicize their activities. But after this event, a number of friends made complimentary comments. I want people to feel more at ease about discussing peace issues. If we can create an atmosphere where being active is seen as attractive, more people will get involved.

Any final thoughts?

Kageyama said during her talk at the end of the evening, “The government might have declared the war is over, but for those who experienced it the war is never over.” I think this is what many people who testify to their war experiences want to convey. Allen’s talk illustrated this point very well.

Chika’s description of her relationship with Nelson is interesting because it bears all the hallmarks of the complex remembrance of Japanese soldiers and their actions within Japanese collective memory of World War II. Her disbelief that “kind and engaging” Allen could have killed people matches the disbelief that many relatives of Japanese soldiers have felt during the postwar on learning of their relatives’ war actions. [12]

The veteran defies easy ideological or emotional categorization for future generations, particularly those imbued with anti-war sentiment: identification with the soldier through a close personal relationship may conflict with abhorrence of his actions; the psychological and physical wounds suffered by the soldiers elicit sympathy but this must be set against the suffering he inflicted on others. Often the only way to reconcile these contradictory feelings is by witnessing a conversion in the soldier from the man he was then (in Vietnam, or the Asia-Pacific War for Japanese soldiers) to the man he is now.

***

Chika was refreshingly honest about why she started her activism. Initially she was passive and reacted mainly in response to invitations from others. A university friend first got her involved in A-bomb-related peace activism in 2006 (when she went to the World Conference against A & H Bombs for the first time). Her trip to Yausubetsu in August 2007, when the seeds of Allen Nelson’s talk were sown, was also the result of an invitation from a friend. Hers is activism that grew out of social relationships rather than ideological fervor.

While social networks can encourage activism, Chika’s comments above also illustrated why students might be reluctant to get involved, or why student activists are sometimes reticent about publicizing their activities. Some members of the organizing committee for Nelson’s talk had even asked that their names not be included on the list of organizing committee members. We discussed this issue and concerns about discrimination against “leftwing activists” by employers were raised. The committee members had heard stories of the SDF compiling lists of activists, or of activists who repeatedly failed exams to become komuin (civil servants). While it is difficult to verify such hearsay, the recent publicity surrounding punishment of teachers who refuse to stand for the flag or sing the national anthem at school ceremonies [17] lends plausibility to the belief that potential employers might conduct background checks and screen out “undesirable” employees, particularly in the public sector. For this reason a decision was made not to put students’ full names in this paper.

However, for those openly involved in activism the imperative outweighs the risks. For Shimpei there was a clear personal imperative to be involved in activism.

Shimpei, why did you get involved in peace activism?

It was quite natural for me to think about war from an early age. My parents named me Shimpei: the characters mean “believing in peace.” But there are two main reasons my interest in war and peace grew.

First, my family lives near the Atsugi Air Base (in Kanagawa). We have American soldiers living nearby and I have often walked by the fence surrounding the base. Fighter jets fly overhead and the noise is deafening. When I was at school it was often difficult to hear the teacher’s voice in class. During the 1991 Gulf War the skies went very quiet, presumably because the fighters were needed in the Gulf. This is when I really sensed that the war had begun. Plus, I saw American soldiers carrying guns within the base perimeter after the September 11 attacks. We could feel the tension in our neighborhood. People who live near bases tend to sense war and peace issues much more in their daily lives.

Second, my grandmother was 8 km from the hypocenter of the

Consequently, I consider myself to be a third generation hibakusha. Inside of me there is what Kenzaburo Oe refers to as “Hiroshima-teki naru mono” (characteristically Hiroshima-like person). [18] I interpret this to mean overcoming the fear of death that exists because of the A-bomb experience, the daily fight to be optimistic about the future, and a fervent longing for peace. However, I feel strident activism is inappropriate and my deepest hope is that the A-bomb anniversaries each year can be remembered with quiet dignity. For a long time I did not want to broadcast the fact I was a third generation hibakusha. I did not want to be looked at differently from others, or give the impression that I thought my views were somehow special. This was probably part of being a “characteristically Hiroshima-like person.” But I now think it is probably more important to speak out given the aging and passing of the war generation.

Consciousness of myself as a third generation hibakusha started in elementary school. My older brother (then aged 12) interviewed my grandmother for a summer research project. A few years later, when I was about 11 or 12 years old, I became more interested in war and peace issues. It was around the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the end of World War II. There were many programs about the war on television. I persuaded my parents to buy the complete manga version of Barefoot Gen by Nakazawa Keiji and read it all that summer. [19] The manga treats many war issues other than the A-bombs, from the oppression of antiwar sentiment during the war to work in military factories. As my interest developed, I also read about

This is how I became active both to protect the Constitution and oppose war. I was at the forefront of opposition to the wars in

Unlike Chika, whose activism developed through social networks at university, Shimpei’s activism is rooted deeply in his family history. His testimony indicates the fine line that many Japanese people feel they have to tread when drawing the lessons from World War II. A sense of victimhood may be strongly and justifiably felt, but overt self-righteousness can quickly draw skeptical or even critical reactions from others. Shimpei counters this by considering Japanese aggression as well as Japanese victimhood, hence his overt criticisms of the Japanese government’s treatment of war responsibility issues and concern about constitutional revision. Consequently, while Japanese “victim mentality” concerning World War II is often criticized internationally, Shimpei’s testimony indicates why much activism on aspects of Japanese victimhood, particularly the A-bombs, goes hand in hand with opposition to Japanese militarism, past or present: peace messages from Hiroshima and Nagasaki have little international currency if they omit Japanese aggression and are couched in the nationalistic language of unique Japanese victimhood.

***

The other two members of the organizing committee, Udai and Yasunori, are both active in the Save Article Nine movement.

Udai, how did you become involved in activism?

There are two main reasons. First I have felt strongly since I was a child that I do not want to die or kill others in war. When I was small I saw the kamikaze film Summer of the Moonlight Sonata [20] and an exhibition about

The second is that having come to university, joined the Save Article Nine society and become active in campaigning for the abolition of nuclear weapons, I have found a lifestyle and raison d’etre in my activism. During the dark days of the Asia-Pacific War there were brave people who risked their lives to oppose

Yasunori, what about you?

Article Nine was born out of the sad experiences of the last war. It expresses the resolution not to go to war through making

For these reasons I became active in the Save Article Nine movement. Many people died in the last war and I think their hopes and wishes are encapsulated in Article Nine. History is the aggregate of all people’s lives and is shaped by all people, famous or unknown. I want to be an active force in the unfolding of history, and preserving Article Nine is one way of doing that.

The four members of the organizing committee expressed a variety of personal, social and ideological reasons for their involvement in peace activism. But what is striking about all their motivations is the complex interlinkage between various war, peace and social issues, from the A-bombs to Japanese war responsibility, from the bases issue to constitutional revision. This is representative of Japanese “popular pacifism” throughout the postwar. For example, Mari Yamamoto has highlighted how peace activism by union activists in the postwar was frequently linked into campaigns on socio-economic issues [21], while the Henoko base issue brings together contemporary peace activism with environmentalism. The committee members’ testimony also illustrates how memories of the Asia-Pacific War and issues stemming from Japanese war responsibility are central to understanding all war and peace discourses in contemporary

V. Allen Nelson Returns to

The organizing committee and I decided to ask Nelson for a follow-up interview. We contacted Yamamoto Koichi, the Christian minister in

I first met Allen in the autumn of 1998. Allen participated in a research group I was involved with that was investigating SDF bases. Since then he has always stayed with us in

Nelson started coming to

I am a minister. It is my responsibility to prevent the taking of life. I feel a deep responsibility for what has happened in

We did not have to wait long for another chance to meet Nelson. Koichi phoned to let me know we could meet Nelson on

Then, just as we were preparing for the interview, an incident occurred that brought back many memories of 1995 and the original trigger for Nelson’s visits to

Against this backdrop, the organizing committee and I interviewed Allen Nelson. He started by explaining how he became involved in “counter-recruiting” in

“I certainly didn’t come out of

It would be many years later, when his son came back from high school one day with a bundle of army recruitment materials, that Nelson’s life turned.

The recruiter had come to the school. As a parent I freaked out. I was so upset that I went to the school to talk to the principal. Why is my son coming home with army recruiting material before financial aid forms for university? The principal explained how the army offers opportunities to kids. OK, but where are the alternative talkers? I said I would like to give a talk, too. Next time the recruiters came, I gave a talk, too. Afterwards, some of the kids asked me to go down to the recruiting office with them.

From this starting point, Nelson’s activities snowballed. He eventually set up an office in

The interview touched on many other issues. [24]

On his counter-recruiting work:

Surprisingly the recruiters like me! Most of those recruiters have never done nothin’! I was 18 when I went to Vietnam and 19 when I came out, but I had four and a half rows of combat ribbons, which is unheard of someone that young. So when I would walk across base and these first or second lieutenants had one or two ribbons (laughs), they would see me and harass me something horrible! “Come here. Did you earn this?”

Recruiters like me. I can talk their language. After we do a presentation we go down to the lunchroom and they say, “Thanks, we can’t tell them what you tell them.” But recruiters are like salesmen who know the car isn’t gonna work but have gotta make money (laughs). They know it’s a piece of junk but they have a quota. I’m just as honest with the children as I can be. I never have a problem with recruiters.

But you don’t ever encourage kids to go into the army do you?

I don’t encourage them, but I have to be real. Some of the kids I work with are extremely poor. We have some communities in

On why he comes to

It was 1995. I came home from work one day and I heard on the news: “Okinawan girl raped by three US Marines.” I thought I had misheard something. I thought the bases had closed after the Vietnam War. I saw no reason for them to remain open. With the rape of the girl it just hit me: “What’s goin’ on?” I knew the Okinawan people were suffering. I was an abuser. I have seen it. Even though I never beat Okinawan people I saw guys who did and I did nothing to stop it. I knew the sort of violence that was going on.

I spoke to some of my friends who are peace activists. A Japanese guy married to an American woman I knew through the Quakers had started a group called Remove the Troops from

So that’s how I got involved and started coming to Japan. Every time I came over, after I got back I said, “Right that’s it, no more,” but then another call came saying, “Can you come back?” All of a sudden it’s been twelve years.

How do you divide your time?

It’s about 50-50. I spend six months a year in

On overcoming PTSD:

Being honest is the bottom line. I feel we can’t move on if we can’t reconcile. You can’t reconcile if you’re not honest. People who read my book probably think I went into therapy to get help with PTSD and that I was so honest. Well I was not. I made him [Dr Neal Daniel] work. I wasn’t giving up nothin’! I could see him pulling his hair out. “Why don’t you just be honest? It’s part of the healing process,” he would say. But I couldn’t. How do you say, “I killed kids”? How do you say that? So when Daniel asked those kinds of questions, “How did you feel when you killed kids?” I would say, “I didn’t kill kids”. “Are you sure?” “No I didn’t.” I was in denial, total denial.

It took him a long time to break me down mentally. We had two types of therapy: one-on-one and big group therapy [with other

After about 13 or 14 years of therapy we started the session with, “Why did you kill people?” It was such a hard thing, like me pulling my own teeth. The reality was that I killed people because I wanted to. Now, why I wanted to, that’s another issue, but I wanted to. It was a very, very painful realization. But, it was as if something unlocked inside of my head. And that was when I was able to talk about this stuff. I realized I had a responsibility – to my friends who had died and the Vietnamese people who had died – to tell their stories. They’re dead. They can’t talk about it.

I’m lucky that I’ve been able to find my voice. I had a wife who was very supportive and a very understanding son who encouraged me. It was very difficult for my family because they couldn’t walk around at night. They could not go to the bathroom until the sun came up because when the sun went down I snapped right back on patrol in

The clincher came on one of those “sit down and you’re still sweating” days in

That first type of therapy didn’t work very well for me because it was drug therapy. They give you all sorts of mood drugs – for when you wake up, go to sleep. After three years of this I said to myself, “I don’t wanna take this for the rest of my life.” So when we moved to the

That was the turning point. Once he was able to help me to help myself, that’s when I realized I wanted to tell the truth about this stuff.

On the government’s treatment of veterans:

Some German students were staying with me and they referred to soldiers as “beer.” When the bottle is full, like when a soldier is in uniform, it is valuable and treated with care. When the beer is gone the bottle is trash: it gets in the way or has to be thrown away. When soldiers leave the army, they are discarded, too. This really made sense to me. …

Anything that happens to you in the military, except your arms and legs getting blown off, you have to prove it’s military related. If you’re poor before you went into the military, and you’re poor when you get out, where are you gonna get a specialist to document your claim? What if you want compensation because you can’t sleep at night or you have mental stress? We had a lot of young people commit suicide after they came back from

It’s not about being in a situation where you have to go on patrol. It’s about being in an environment where you can blink your eye and a bomb will go off and you’re gone. There’s no tomorrow. What you have is now. When you are living under that kind of tension, you come home and it’s still on top of you. I thought about committing suicide when I came home from

On the SDF in

When the troops were first in

This is the kind of pressure the family has been taking. It’s not just the soldiers that have PTSD. Then the guy comes home and he’s completely different, too. I saw a documentary about the SDF in

If you were president, what would you do to reconcile with

The first thing I would do is give as much money as possible for the Agent Orange victims. That chemical is still very strong in their environment.

The second thing I would do is apologize. I would ask sincerely for them to forgive us for attacking their country when Ho Chi Minh was voted president legally. But the Americans didn’t want him because he was a communist. So we set up a puppet government in the South and used it as a launch pad for overthrowing Ho Chi Minh. We have to apologize for the attack. They never did anything to us.

I would open up real exchange: cultural and educational. When I went to

Here is another story from

So, if I were president I would help those suffering from Agent Orange. I went to

After Allen Nelson recounted seeing some of the victims of Agent Orange, he went quiet. After a long interview in which he had been passionate and often warmly humorous, this was obviously something that troubled him deeply.

Reflections

Peace activism in

The seven key figures – Allen Nelson, Kageyama Asako, Yamamoto Koichi and the four students Chika, Shimpei, Udai and Yasunori – were drawn together by their protests at the SDF’s Yausubetsu firing range and Nelson’s talk at Hokkaido University, but beyond this their interests are extremely diverse: education and counter-recruiting in New Jersey (Nelson), the documentation of Korean forced labor in Hokkaido during World War II (Kageyama), philosophical principles based on Christian faith to prevent killing (Yamamoto), interviews with hibakusha (Chika), the bases issue and being a third-generation hibakusha (Shimpei), and activism to save Article Nine (Udai and Yasunori).

Furthermore, their activism is not limited merely to concerns of war and peace: Shimpei’s testimony touches on issues of health and disability stemming from exposure to radiation; Nelson’s testimony treats issues of poverty as important within military recruitment; Udai discusses how peace activism relates to student lifestyle; the decision to use the students’ first names only illustrates the possible link between activism and employment prospects; and the protests against the Henoko base in Okinawa depicted in Marines Go Home (narrated by Kageyama) shows the overlap between environmental issues and peace activism.

These observations mirror the findings of Mari Yamamoto in her study of grassroots peace activism: Japanese “popular pacifism” defies simple ideological or political characterization and is as diverse as the eclectic priorities of those who become involved. Peace activism has gone through various phases in the postwar: the first phase in the 1950s and 1960s focused on antinuclear pacifism and opposition to the US-Japan Security Treaty (AMPO); the second phase encompasses the anti-Vietnam War movement and the accompanying awakening of interest in Japanese aggression against neighboring countries during the Asia-Pacific War; and the third phase has linked anti-US base activism to opposition to Japan’s growing military involvement abroad since the 1990s and the threat to Article Nine. [30] The portrait of

The issues promoted by the activists whose voices are presented here raise many new questions. For example, would the removal of American bases from

The activists mentioned in this paper face significant obstacles in the pursuit of their goals, and some objectives may be unrealizable in their lifetimes. But, this paper has focused on the deep-rooted motivations underlying their peace activism, and why, despite the obstacles, they actively embrace the message that ended Allen Nelson’s talk at Hokkaido University: “Peace begins with each and every one of you”.

Postscript

This paper began with a quotation from Allen Nelson’s testimony that described his part in the birth of a baby in the midst of the death and destruction of the Vietnam War. After the young woman gave birth, she ran out of the bunker and into the jungle. Nelson never saw her again and never learned what happened to her or the baby.

As final preparations were being made for the publication of this article, another

Philip Seaton is an associate professor in the Research Faculty of Media and Communication,

I would like to thank Doug Lummis and Mark Selden for their comments, and all the contributors (Allen, Asako, Koichi, Chika, Shimpei, Udai and Yasunori) for reading and checking the manuscript.

Posted on April 21, 2008.

Notes

[1] Allen Nelson (2006) To End the Misery of War Forever: No Reconciliation, No Peace,

[2] A collective decision was made to use only students’ first names in this paper.

[3] Allen Nelson, interview conducted by Philip Seaton and the organizing committee,

[4] Nelson, To End the Misery of War Forever, p. 1.

[5] The Marines Go Home Page is: here.

[6] In January 2008, environmentalists won a partial victory when “U.S. District Judge Marilyn Hall Patel ruled Thursday [

[7] Kawazoe Makoto and Yuasa Makoto, “Action Against Poverty: Japan’s Working Poor Under Attack”, Japan Focus.

[8] Yamamoto, Mari (2004) Grassroots Pacifism in Post-war

[9] More accurately speaking, the “interview” with Chika is an abridged version of her written submissions supplemented by her comments during meetings. The same is true of the other three “interviews”.

[10] Chika went with 8 other young adults from

[11] Nelson’s dislike of insects also features in the manga version of his story: Saeguchi, Mr. Nelson did you kill the people?, p. 24.

[12] Seaton, Philip (2007)

[13] Dower, John (1999) Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II,

[14] The Chinese Returnees Association (Chukiren) homepage; The Winter Soldier Investigation

[15] The site wintersoldier.com is “dedicated to the American veterans of the Vietnam War, who served with courage and honor” and disputes confessions of atrocities; in Japan’s case, nationalists such as manga artist Kobayashi Yoshinori have attacked the confessions of Chukiren members and other soldiers. Kobayashi simply dismisses then as “brainwashed”: Kobayashi Yoshinori (1998) Sensoron,

[16] My own work on Japan, especially Japan’s Contested War Memories, covers many of the themes in research on Vietnam, for example, McMahon, Robert J. (2002) “Contested Memory: The Vietnam War and American Society, 1975-2001”, Diplomatic History, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Spring 2002), pp. 159-184. See also Laura Hein and Mark Selden (eds) (2000) Censoring History: Citizenship and memory in

[17] See for example John Spiri, “Sitting out but standing tall: Tokyo Teachers Fight an Uphill Battle Against Nationalism and Coercion”,

[18] The phrase in Oe’s Japanese original that Shimpei refers to has been translated as the “truly human character of the people of Hiroshima” in Oe, Kenzaburo (1995, translated by David L. Swain and Toshi Yonezawa) Hiroshima Notes, New York: Grove Press, p. 17. My translation “characteristically Hiroshima-like person” is based on how Shimpei explained his interpretation of this phrase to me.

[19] On Barefoot Gen, see Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, “Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy,” Japan Focus.

[20] The Japanese film Gekko no Natsu (1993) is based on an actual incident. Two music students who have become kamikaze pilots visit a school to play Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata on their final night before flying their missions. Fast forward to the 1980s and the schoolteacher who let the pilots play during the war years is campaigning to prevent the old piano being thrown out. She embarks on a journey to find out what happened to the pilots and discovers one of the pilots survived. The film is rich in themes of survivor guilt and the futility of war. The actual piano is now displayed at the entrance to the

[21] Yamamoto, Grassroots Pacifism in Post-war

[22] See Johnson, Chalmers “The ‘Rape’ of Okinawa,”

[23] The

[24] Another published transcript of an interview with Allen Nelson is “A Vietnam War Veteran Talks About the Realty (sic.) of War: An Interview with Allen Nelson”, Nanzan Review of American Studies (2004) Volume 26, pp. 43-56. Available online (Accessed

[25] The program is explained on this site (accessed

[26] Homepage. An article about Nelson is available here (Accessed

[27] This point had been made to me in an interview with another veteran, Mitsuyama Yoshitake, a Japanese veteran of the Battle of Okinawa. Following our interview (26 September 2007), Mitsuyama sent me a copy of an article from Hokkaido Shimbun which described how the seven suicides among SDF troops who had returned from Iraq constituted a rate three times the standard suicide rate among SDF personnel). Hokkaido Shimbun, “Iraku haken, jieikan no jisatsu 7-ken ni”,

[28] “On March 10, 2005 Judge Jack Weinstein of Brooklyn Federal Court dismissed the lawsuit filed by the Vietnamese Victims of Agent Orange against the chemical companies that produced the defoliants/herbicides that they knew were tainted with high level (sic.) of dioxin. Judge Weinstein in his 233 page decision ruled that the use of these chemicals during the war, although they were toxic, did not fit the definition of ‘chemical warfare’ and therefore did not violate international law.” Online (Accessed

[29] Link available here.

[30] Yamamoto, Mari “Japan’s Grassroots Pacifism”, Japan Focus.

[31] The