Abstract: This article examines how issues “closest to home”—family, friends and furusato (home town/area)—affect Japanese war memories. It draws upon testimony illustrating the importance of “home” and analyzes how family and local identities impinge on the evolution of cultural memory and war commemoration. Examples are drawn from Hokkaido.

Introduction

In 1938, Ito Yoshimitsu enlisted in the Sapporo Tsukisamu 25th regiment, part of the Seventh (Hokkaido) Division of the Imperial Army. He saw action in China before transferring to the military police (kempei) in 1943. At the end of the war he was stationed in Celebes in present-day Indonesia. There he was arrested by the Dutch after the war and executed as a BC class war criminal on 4 October 1948. Ito had been convicted of serious torture, including beating, burning with cigarettes and force-feeding water to Indonesian prisoners. [1]

Fig. 1: Map of Hokkaido and the Northern Territories

Before his execution, Ito sent a last will and testament (yuigon) to his family and friends. In his final letter to his father he said that he would be vindicated by history. He had carried out his duties during the war but these had been considered in violation of international law and labeled organized terror. He prayed that his actions would not bring shame to his parents. [2]

Another recipient of a final letter from Ito was his childhood friend Kakiuchi Toshio. Ito wrote, “I will depart this world labeled a war criminal. But as I look back over my actions, I have nothing to be ashamed of. I am not going to write troublesome things to you. I was a Japanese soldier and I just hope you will believe me.” Instead of details about his service, Ito reminisced in fleeting references to people and events from their childhoods (such as teachers or a school sports day) that obviously held rich significance for Ito and his “unforgettable friend”. [3]

Ito’s last words and letters form the basis of a book called Giving One’s Life to One’s Country (1988), edited by Kakiuchi. In his editor’s afterword, Kakiuchi wrote, “When I first saw Ito’s will and testament I immediately dreamed that it would be published one day as a book. This book is the realization of that dream.” These words, written in his seventies from a hospital bed, may be considered part of Kakiuchi’s own last will and testament: “In life you should leave something for the generations that follow,” he remarks. [4] The death of his friend obviously affected Kakiuchi. For the book he collected documents, testimony and poetry from Ito’s friends, comrades and relatives; and the introduction, written by the head of the Hokkaido Rengo Izokukai (Hokkaido branch of the War Bereaved Association), laments how the hardships and bravery of the war generation are being forgotten forty years on.

Kakiuchi’s book is just one illustration of the important but often overlooked role that family, friends and furusato (home town/area) have played in preserving and shaping Japanese memories of the Asia-Pacific War. The international media, and to some extent the academy, has tended to focus on “official” and “controversial” topics. [5] While controversies such as official prime ministerial worship at Yasukuni Shrine are undoubtedly important, this article employs a social rather than political or national history approach to examine how those things “closest to home”—particularly family, friends and furusato—shape Japanese memories of the Asia-Pacific War, 1937-45. It is a method that merits application to wars and war memories elsewhere, too.

Six decades after their defeat in the Asia-Pacific War, the Japanese people have not yet achieved a consensus on how to narrate and interpret that war, not only because of a wide range of war experiences, but also because Japan’s contested war memories are a product of divisions regarding the morality of Japan’s war aims and conduct. Opinion ranges widely from progressives (who condemn a war of aggression and call upon the Japanese people and government to accept war responsibility) through to nationalists (who argue that Japan fought a just war which resulted in the liberation of Asia from Western colonialism). [6]

Explaining divisions and diversity within Japanese historical consciousness is only possible by investigating beyond the narrow confines of state-centric analysis (focusing on the Japanese government and “official history”) and national identity. Focusing on the perspectives of family, friends and furusato illustrates how identities other than national identity impact on historical consciousness in ways that may resonate, clash with, or add nuance to the various competing cultural narratives of war history and responsibility within contemporary Japanese society.

Identification with Family, Friends and Furusato in War Generation Testimony

Identity is a statement about how people define themselves and the groups to which they feel they belong. Identities are multilayered and situational: they are multilayered because identities have multiple co-existent forms—such as gender, religion, class and generation—and they are situational because identities assume greater or lesser prominence according to the situation and/or environment. The assumption of different identities according to the situation is a more or less conscious decision to associate with or assert difference from another person or group. Within the “composure” of war memories, the memories or narratives of groups that people belong (or aspire to belong) to assume particular prominence, while the memories and narratives of groups with whom there is weak identification may be marginalized or ignored. [7]

National identity plays a key role in World War II memories since it was the largest and bloodiest “clash of nations” in history. But World War II history need not only be viewed in national terms. When memories are filtered through national and other forms of identity without contradiction or discord, family, local and national identities may be mutually reinforcing. This was evident in the story of Ito Yoshimitsu: Kakiuchi’s book united family, friends, the local War Bereaved Association and nation (the book’s title was Giving One’s Life to One’s Country) in a conservative-nationalist narrative that lauded a soldier’s memory, despite his conviction and execution for torture. Identification with Ito on a family or friendship level allowed friends and relatives to believe his protestations that he had done nothing of which to be ashamed. Japanese conservatives could also identify with Ito’s story on a more ideological level: he was another young patriot who had died in the service of his nation.

On other occasions, however, forms of identity other than national identity may provide a rationale for criticizing Japanese war conduct. Gender identity has assumed particular importance in this regard since the eruption of the “comfort women” issue in 1992-3. [8] On hearing the harrowing testimony of sexual violence and enslavement suffered by “comfort women,” Japanese women have often empathized and identified with “fellow women’s sufferings” and adopted a critical stance towards the Japanese military. Identities such as gender or a role-identity such as “feminist historian” may also be mutually reinforcing with other identities, such as family or regional identities. For example, the Sapporo Women’s History Research Group (Sapporo Joseishi Kenkyukai) has combined women’s and local history to forge a critical historical consciousness of World War II in its publications. This is epitomized by Nishida Hideko’s research into Korean women working as “laborer comfort women” (romu ianfu) in “comfort stations” set up to serve Korean men working as forced laborers in Hokkaido’s mines: a macabre “forced sexual labor for forced laborers” arrangement that points to multiple layers of victim and assailant across gender, regional and national groups. [9]

Aspects of people’s multilayered identities, therefore, are used individually or in complex combinations according to the situation to determine whose war experiences are identified with and the nature of historical consciousness. Within this process, family, friendship group or furusato identities are just three of the many identities that may be employed, but they are significant for being based on the closest emotional, biological/social and spatial bonds that human beings possess.

National identity is now often described as the sense of identification with, in Benedict Anderson’s suggestive phrase, the “imagined community” of the nation. [10] By contrast, the closer one gets to “home” the less is “imagined”. In particular, the family is the ultimate “unimagined/real community” in the sense that it is built on intimate knowledge of the personalities and day-to-day and face-to-face actions/experiences of relatives.

Consequently, countless references to family, friends and furusato feature within the testimony of the Japanese war generation. For example, Miyamoto Natsu moved to Manchuria near to where her sister lived in 1941. She married the following year and in 1945, at the time of Japan’s defeat, had a 2-year-old baby, Harumi. Harumi caught measles during the long journey on foot and by train back to Beijing and then by boat home. With no doctors and little food available, Miyamoto tried unsuccessfully to breast-feed Harumi, an experience she describes as deeply painful (kokoro kara kuyanda). When Harumi died, she continued her journey with Harumi’s remains in a tin can. Miyamoto and her husband lived in Saitama after the war, but in a poignant illustration of the enduring depth of both parent-child and furusato bonds, she bought a grave plot in Sapporo in the early 1990s and erected a memorial stone to Harumi. She moved back to Hokkaido after her husband died and in 2005 at age 91 she told her story to the regional newspaper, Hokkaido Shinbun. [11]

Miyamoto’s testimony was prefaced by the comment, “The weak are the first to suffer.” The “war is bad” and “this is how our family suffered” tone that infuses her testimony is representative of the much-maligned phenomenon of Japanese “victim mentality” (higaisha ishiki). However, it is appropriate to distinguish between victim mentality as a response to individual trauma and victim mentality as a denial mechanism regarding the extent of Japanese aggression. It is also worth noting that such war memories may provide one foundation for the peace consciousness that has remained one important Japanese response to war and defeat ever since.

As well as the biological and emotional strength of family bonds, a further key reason why Japanese war memories start “closest to home” is that many families experienced the horrors of war together. The war affected families as a unit in both the homeland (particularly in the experiences of air raids and mobilization for the war effort) and in Japan’s colonies (colonial settlers who were caught up in fighting and/or experienced long painful journeys home). For example, after growing up in the Tokachi region of Hokkaido, Maeda Takeshi was a sixteen-year-old flight school cadet in Gunma prefecture when in October 1944 his “first love” (hatsukoi) was shot through the head as they ran away together from a strafing American fighter. “I was away from my parents and K’s house was like a second furusato for me,” Maeda recounted. He describes running in tears to tell K’s parents of her death. [12] Such shared narratives of suffering among family, friends and local community may lead to powerful mutual reinforcement among the surviving members of the group over time.

But family stories from the home front are not only of family or Japanese suffering. Some family stories are of Japanese atrocities that underly critical stances on Japanese war conduct. For example, Azuma Haruko moved to Hokkaido after her father, a successful rice farmer from Saitama near Tokyo, was harassed by the Special Police (Tokko Keisatsu, the domestic “thought police”). His “crime” was to have written a letter to the Agriculture Ministry criticizing wartime agricultural policy. Fearing for their lives, they moved to Yubari, a center of the Hokkaido coal industry. Her father hid his background and got a job in the mines, eventually becoming a kitchen orderly. On her way to school, Azuma sometimes witnessed the brutal beatings of Korean forced laborers, their mouths stuffed with a slipper made of conveyor belt material to silence the screams as they were beaten senseless. When the war ended, the Korean laborers formed a vigilante group to find the camp overseer. The overseer begged her father to hide him in a closet. Azuma shook with fear as she thought of what the Koreans would do if they found him. As she recounted this story sixty years on, she broke down and confessed she had never told this story to anyone, not even to her husband. It had remained a shared yet unspoken family secret, a powerful influence on her enduring image of the “arrogance” in Japan’s inhumane treatment of Koreans during the war. [13]

Family, friends and furusato feature prominently in military as well as civilian testimony. Regional memories are a particularly important feature of soldier memoirs because the Japanese army was organized into regional battalions. In a manner similar to the “lost generation” (the concentration of war dead from particular social or geographical groups) created by the region- or profession-based “pals battalions” in the British Army during World War I, Japanese soldiers from the same prefecture fought and died together in World War II. The Seventh (Hokkaido) Division was headquartered in Asahikawa (until 1944, when it moved to Obihiro to be nearer to potential invasion beaches in Eastern Hokkaido). Today, Asahikawa houses a large SDF base and is also the location of Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja (“Nation Protecting Shrine,” the prefectural branch shrine of Yasukuni Shrine), which enshrines 63,141 local soldiers and is the principal commemoration site for fallen soldiers from Hokkaido and Sakhalin. [14] Within Hokkaido’s military past, the Nomonhan Incident (a clash with Soviet troops on the Mongolian border in 1939), the “banzai charge” on the Aleutians (1943), and Guadalcanal are just some of the battles in which soldiers from Hokkaido died en masse side-by-side.

The battle most deeply imprinted in Hokkaido military history is the Battle for Okinawa in which 10,065 people from Hokkaido died, the largest number from any prefecture after Okinawa. One soldier who participated in the Battle for Okinawa was Ueno Seiji. His published diaries document his redeployment from China in 1944, nearly dying of dysentery, air raids and the fighting itself in brief but arresting entries. For example, one undated entry (probably from May 1945) simply reads: “A baby strapped to its mother’s back with an obi (kimono belt) doesn’t know its mother is dead yet.” [15] Ueno also thinks of home and on a couple of occasions expresses relief that Hokkaido was not caught up in such fighting. [16]

Ueno’s commentary on his diaries fifty years on (in 1995) provides another example of how family, military unit and national identity can combine to create patriotic historical consciousness. Ueno dedicates his diary to his fallen comrades (naki sen’yu) and comments:

The Pacific War continues to cause a lot of problems. There is a lot of harsh criticism from intellectuals, the public and even abroad. Whenever I hear this I feel sorry for the war dead. The critics just focus monotonously on the suffering and damage. But looking at it from a different perspective, I think the Japanese contributed to the change from colonization to liberation of other colored races around the world. It is a fact that Nobel Peace Prize winners from southern Asia have said that it was thanks to Japan that they could gain their independence. [17]

Ueno’s racial identification with liberated “colored races” (yushoku jinshu) and his attempt to find meaning in his comrades’ deaths underpin his nationalistic (perhaps also anti-Western) “affirmative view” of the Greater East Asian War.

Among supporters of affirmative views of Japanese war conduct, another form of private document has assumed canonical status: the final letters home of kamikaze pilots before they flew their missions. The Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots in Chiran, Kyushu, has become the main commemorative site for the kamikaze, and the pilots’ letters are prominently displayed. [18] Despite the sometimes nationalistic and patriotic-sounding rhetoric in these letters, as Tanaka Yuki has observed, they are infused with references to family, friends and furusato. Many spoke of dying to protect their country. “However, as testimonies of dead and surviving pilots clearly show, their idea of ‘country’ was far from the nationalistic notion of ‘nation-state.’ For most of these young students, ‘country’ meant their own ‘beautiful hometowns’ where their beloved parents lived.” Other key motivations for flying included defending the honor of their mothers (who would be afforded respect as the mother of a kamikaze), loyalty to flight-mates and the desire not to be seen as cowardly. [19]

Thirty-four pilots from Hokkaido flew missions from the base at Chiran. One was Maeda Hiroshi, whose last letter to “Father” (in its most filial form, chichiue-sama) ended by saying there would be no need for his grave plot but that he wanted his soul to rest next to his dear departed mother. [20] With a banzai to the emperor and his unit, and a poem comparing his death to falling cherry blossoms, Maeda flew to his death. [21] Maeda’s story will be discussed again later as Kuriyama High School (just north of Chitose) staged a play about his life in 2005, on the sixtieth anniversary of his death.

Inferring the kamikaze pilots’ real feelings about their impending deaths in such letters home requires a measure of reading between the lines: all final letters to families had to pass the military censors. But further evidence of soldiers’ thoughts for family, friends and furusato just before they died is evident in the testimony of Inomata Kiyoko. She was a fourteen-year-old schoolgirl when her older brother told her about his experiences in China while on home leave. Recounting an incident when he had cried as he held a dying comrade in his arms, he said: “Y’know Kiyoko, when soldiers die they don’t shout banzai to the emperor. They say their mothers’ and wives’ names.” [22] When he was reassigned to the defense of the Aleutians his parting words were, “Take care of Mother.” After his death in the banzai charge on 29 May 1943, Kiyoko felt hurt whenever people congratulated their family on his “honorable death.” How to reconcile patriotism and bereavement when for many people the cause was ultimately futile and even discredited is a dilemma that many bereaved Japanese families have struggled with in the aftermath of the war.

The majority of published and archived testimony thus far has focused on the suffering of Japanese individuals, their relatives, friends and neighbors. But, many people have worked tirelessly to expose Japanese atrocities. As I have argued at length in the story of a weapon scientist’s niece who was exploring her uncle’s wartime record, exposing war crimes within family history must run the gauntlet of family and local opinion: not everyone in families (or alternatively veterans groups or local communities) is appreciative of people digging up uncomfortable secrets. [23] Particularly among veterans there may be pressure (ranging from intimidation to death threats) from rightwing (uyoku) groups or fellow veterans to maintain silence regarding atrocities. Nevertheless, a number of ex-soldiers and conscientious scholars, journalists and publishers have worked bravely to present confessions of the Japanese military’s war crimes.

One example of a local progressive group in Hokkaido that has collected confessional testimony is the “Delving into our Hometown Sapporo” Society (Sapporo Kyodo wo Horu Kai). In one of a series of books documenting the roles of Hokkaido people in Japan’s war, the Society presents the testimony of Tanifuji Yoshio. He was a miner before being drafted into the Seventh Division in 1943 and sent to China. The training was merciless. Tanifuji describes a soldier, named only as M, from Sapporo who was beaten and insulted repeatedly by senior officers to the point where he committed suicide. He also describes in chilling detail the sanko sakusen (the “kill all, burn all, loot all” policy) which earned the Japanese army its infamous reputation throughout China. He describes arbitrary killings of prisoners, water torture (filling people’s stomachs with water then jumping on them), rape, burning houses and looting. “It was only natural that the Chinese called us riben guizi [Japanese Devils],” Tanifuji comments. [24] After the war he was interned in Siberia and then China. “At first I denied everything claiming, ‘I followed orders. I am not responsible.’ But, thereafter I started thinking about the sadness and pain the victims had suffered as human beings. I understood the weight of my crimes and was resigned to being executed for them.” [25, emphasis added]

As Linda Hoaglund’s commentary on the documentary film Japanese Devils (Riben Guizi) illustrates, such atrocities were often fueled by an addictive, quasi-sexual gratification in killing. [26] The testimony of another soldier, Azuma Shiro (who admits similar atrocities in China), indicates that when Japanese soldiers were indoctrinated during training to think their lives were “as light as a feather,” they could only think of the lives of “Chinks” (chankoro), who they had beaten in the Sino-Japanese war and were beating again, as even less consequential than their own. [27] But Tanifuji’s final comment about seeing the victims “as human beings” illustrates the important role that recognition of the family, friends and furusato of others can play in breaking the cycle of denial and finding the conscience necessary to acknowledge such acts as barbaric war crimes.

Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s important notion of “worthy and unworthy victims” illustrates that the sufferings of victims with whom there is no identification can be ignored or even dismissed as “deserved,” but when there is identification with victims their sufferings encourage a sense of outrage at the perpetrators responsible for their suffering. [28] As such, atrocity is greatly facilitated by the dehumanization of victims, particularly when virulent nationalism or racism makes foreigner others “unworthy” or “subhuman,” as was frequently the case during the Asia-Pacific War. [29] Conversely, if there can be identification with victims “as human beings,” perhaps through seeing the victims as individuals with bonds of love to family, friends and community, victims are made “worthy” and humanized, and the perpetrators of their sufferings can be condemned.

Finally, a survey of testimony of people from Hokkaido would not be complete without mention of the Ainu, the indigenous people of Hokkaido whose land was seized and whose culture was forced into decline by Japanese colonial policy following the Meiji Restoration (1868). Ainu people faced severe discrimination and bullying at school and in wider society, yet when they were needed for the war effort they were expected to be exemplary soldiers like other Japanese. The testimony of one Ainu member of the war generation, Kayano Shigeru, neatly encapsulates all of the themes presented thus far.

In Our Land Was a Forest, Kayano recounts how his oldest brother, Katsumi, died in 1941 of tuberculosis that he had contracted after serving in the Seventh Division in China. He also describes his own experiences in Muroran of naval bombardment and air raids on 14-15 July 1945. [30] Kayano’s text offers a rich, multi-layered view of both the Ainu and Japanese war experience. On one level, he and his family were simply human beings experiencing the violence of war like so many others. His family’s experiences incorporate both civilian (home front) and overseas military experiences, which suggests a complicated combination of victimhood and responsibility within family memories. On another level, as the “indigenous people” of Hokkaido, Ainu war experiences emphasize the unique regional (Hokkaido) nature of some war experiences. So too did Kayano’s experience of naval bombardment. Muroran was bombarded because it contained many heavy war industries but Hokkaido was out of the range of B-29 bombers based in Saipan. The navy was called upon to do what firebombing had done elsewhere in Japan. Finally, on another level, Ainu identity is a clear example of how alternative identities to Japanese national identity may inform a critical assessment of Japanese war conduct.

In sum, the testimony of Japanese people illustrates the complex and diverse ways in which identification with family, friends and furusato have underpinned or challenged identification with the nation. On some levels, the testimony of people from Hokkaido is representative of people from across Japan. But at the same time, family and regional (Hokkaido) memories possess a measure of distinctiveness that adds nuance to broader Japanese war memories. Overall, within Japan’s contested war memories there is no single, dominant pattern in which identification with family, friends and furusato is reconciled with identification with the nation.

Family, Friends and Furusato with Collective Memory and War Commemoration

Given the importance of family, friends and furusato within the testimony of the war generation, it follows that these should feature prominently in collective memory, too. Testimony is the raw material of cultural memory. As people narrate their experiences to others, shared memories emerge among groups. These shared memories compete with each other for attention and prominence within the public sphere. Gradually, shared narratives are incorporated into broader regional and national cultural memories through repeated representation within local and national media. Cultural memories are a “flattened out version” of the most common narratives in a given group, region or nation. [31] Nevertheless the collective memories elicit the identification of many in the group, region or nation because the narratives are broadly representative of many people’s experiences and/or because they offer an acceptable moral, political or historical interpretation of events.

Viewing war history from a local perspective illustrates that collective memories may vary considerably from furusato to furusato. In Hokkaido’s case, the large number of forced laborers in the mines (20 per cent of all Korean and 42 per cent of all Chinese forced laborers in Japan were in Hokkaido [32]) have given narratives of forced labor greater prominence within local history than in other regions. The Soviet role in World War II also features much more prominently in Hokkaido memories compared to the rest of Japan, because many settlers from Manchuria and particularly Sakhalin were repatriated to Hokkaido, including many who spent time in Soviet camps. And the local campaigns to force Russia to return the Northern Territories (the island groups of Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashiri and Etorofu), which were occupied after Japan’s surrender, are visible across Hokkaido on the placards outside official buildings, especially in the eastern city of Nemuro. The Northern Territories issue and its effects particularly on fishermen on Cape Nosappu (which at its closest point is only 3.7 kilometers from the Habomai island group) is an example of how aspects and legacies of war history that are of marginal importance in one region may be of day-to-day significance in another.

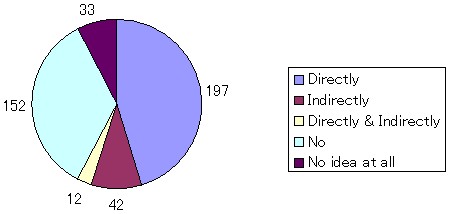

Also central to the development of collective memory is the transition from the war generation’s memories of personal experience to the second-hand memories of the postwar generations. The importance of family, friends and furusato within collective memory can be seen in the standard processes by which the postwar generations today acquire historical consciousness. Awareness of war history among Japanese youth today often starts “closest to home” with a grandparent’s story from the war years (“When I was your age …”). As part of a general survey into historical consciousness that I carried out among university students in Hokkaido in 2004 and 2005, 436 respondents (51 per cent male, 49 per cent female, 236 of whom were from Hokkaido) were asked if they had heard the war experiences of a relative (see Fig. 7 below). Of these 436 students, 197 (45.2 percent) reported hearing the war experiences of a relative directly from that relative, 42 (9.6 per cent) had heard of a relative’s experiences indirectly, 12 (2.8 per cent) had heard both directly and indirectly; 152 (34.9 per cent) had not heard the war experiences of a relative, and 33 (7.6 per cent) gave no answer or had “no idea at all” about their family’s war history. In other words, just over half reported knowledge of their family’s war history. When asked what they had heard, the answers provided a cross section of the various Japanese war experiences: “Grandfather was training to be a kamikaze but the war ended before he could fly,” “Grandmother worked in a munitions factory,” “Grandmother experienced the A-bomb in Hiroshima but is still alive today,” “Grandfather fought in China.”

Beyond the home, school is an important place to receive war history education. Debate over whether the war is taught “adequately” in Japanese schools has continued throughout the postwar, with critics arguing that Japanese aggression is marginalized while Japanese conservatives bemoan the “masochistic” (“too much focus on Japanese aggression”) nature of history education. The truth is somewhere in between and there are marked variations in how much any given child learns, from virtually nothing through to significant war-history-related extra-curricular activities. Moreover, the balance has changed over time with revisions in textbooks and public debate of the issues as well as with generational changes. [33] The Japanese school system may not seem an ideal place to learn about family and local history, given the much-publicized nature of nationally-approved history textbooks and their screening by the Ministry of Education, but nevertheless, family and local history can feature in three particular forms within school education—school trips, testimony meetings at schools, and extra-curricular (club) activities—as part of the loosely-defined “peace education” programme within citizenship or moral education at some schools.

First, “peace education” at school often centers around a school trip to a local history or “peace” museum. In the early 2000s, over a million Japanese children a year visited a “peace museum,” mainly on official school trips and mostly to the museums in Hiroshima, Nagasaki or Okinawa. Japan has scores of other museums, both specialist peace/war museums and generic history museums, that narrate war history, many of them from an explicitly local perspective.

One such museum is the Historical Museum of Hokkaido, whose war exhibits “From Recession to World War II” start with a brief explanation of “War and Hokkaido”:

The army began to invade China which started a 15-year period of war. The development of Manchuria was given priority over Hokkaido, and many emigrants were sent to Manchuria. To make up for the labor shortage in mining and construction projects in Hokkaido, Koreans, Chinese and prisoners of war from the Allied Powers were forced to do heavy labor. Many lives were lost during this period. [34]

This explanation hints at an overall progressivism: the term “15-year war” is the name preferred by progressives (instead of “Pacific War” or the nationalistic-sounding “Greater East Asian War”), the war in China is simply labeled “aggression” (the Japanese placard uses the word shinryaku), and the mention of forced labor is supplemented by two full pages in the 48-page guidebook (compared to one page on air raids). [35]

The exhibits, however, exemplify the predominant “social history display style” in Japanese war exhibits: they focus on the Hokkaido front (including a video about the Hokkaido air raids) and contain a significant family/household element. The artifacts on display include a flag inscribed with messages from friends or neighbors for a soldier to take to the front, an imonbukuro (consolation bag) to be filled with letters and presents to soldiers, wartime clothing (including monpe, women’s work trousers, and protective headgear for during air raids), household items such as a radio and crockery, and a wartime propaganda poster exhorting people to give their metal for the war effort with the slogan: “Your household is a small mine.” While the Historical Museum of Hokkaido does not have the testimony collections that exist in some other museums, most notably at the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, there are a few letters of repatriates from Manchuria and Sakhalin on display.

Overall, the focus is on family, friends and furusato rather than military history, politics or foreign victims. The Historical Museum of Hokkaido had 425,023 visitors, 2000-2006, of whom 133,387 (31.4 per cent) were elementary and junior high school students and 45,411 (10.7 per cent) were high school students. In the period 2004-2006 (for which data is available) there were 874 school trips to the museum, 56.6 per cent of which were for 12-14 year olds (sixth grade elementary and first grade junior high). [36] These students saw a representative form of local and social history exhibits about the war as part of their school education.

The second important form of extra-curricular war education for Japanese children is listening to the testimony of a member of the war generation. As in most “peace education,” the moral is “the terrible nature of war” and not a jingoistic defense of Japanese actions. The archetypal testimony at schools that is reported in the Japanese media is civilian testimony of air raids. For example, the Hokkaido Shinbun reported on 14 July 2006 that in Kushiro (one of the cities affected most by the Hokkaido air raids of 14-15 July 1945), survivors of the air raids had been speaking to children at elementary and junior high schools. [37]. But testimony of other military and civilian experiences can feature, too, provided that it fits within the school’s definition of “peace education.” In the same university student survey mentioned above, 11.2 per cent of the 436 students said that they had heard testimony from a member of the war generation invited to speak at their junior high school, while 18.6 per cent had heard such testimony at senior high school.

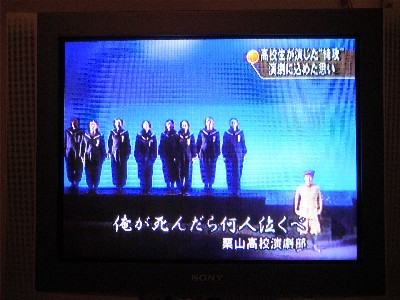

Third, there can be significant war education within a Japanese child’s schooling through club activities. Such club activities may be atypical, but can also become newsworthy and gain wider significance through the local media. For example, the drama club at Kuriyama High School put on a play about Maeda Hiroshi, the Hokkaido kamikaze pilot whose last letter home was mentioned earlier. The play took its title from his last poem, Ore ga shindara, nannin nakube (“I wonder how many will cry when I die”). Written by Sakurai Mikiji, a teacher at Kuriyama High, it was performed at the Muroran Municipal Community Center (shimin kaikan).

On 15 August 2005, Super News on local television station UHB (part of the Fuji Television network) featured the play during its sixtieth-anniversary commemoration coverage. A seven-minute report included extracts from a performance of the play, notably the final scene, when Maeda explains his reasons for flying his mission: “I am not dying for my country. I am dying for the things I love. I am dying to protect my family and furusato.” The monologue is delivered to the audience, but Maeda’s mother is listening to him and interjects repeatedly with the same line: “Don’t die” (Shinde wa dame). Playwright Sakurai states that his message in the play was the importance of life and the need to maintain peace. The interjections of Maeda’s departed mother were a device for putting this message into the play. The play was a great success, bringing tears to the eyes of many in the audience and cast. UHB’s report introduced the section from Maeda’s final letter cited earlier and included an interview with Maeda’s sister-in-law, who tends his memorial stone in the family grave plot. The report closed with a shot of the memorial stone and the comment: “Maeda Hiroshi rests in peace here with his family.”

This news report is revealing on many levels. The play exemplifies how testimony and experiences of the war generation are reworked to fit the meanings of contemporary Japan. The theme of furusato runs through the story: in Maeda’s dramatized motivations for flying, in the fact that a school put on a play about a “local Hokkaido boy” in a municipal community center, and in a local television station’s reporting of the event. And as in so many news reports and television documentaries on Japanese television, interviews with relatives or members of the war generation feature prominently. Overall, this report and play illustrate how social history and themes of family, friends and furusato can feature prominently in cultural and media representations of the war in Japan today.

Family, friends and furusato also play a central role in official war commemorations throughout Japan, particularly on the war-end anniversary, 15 August. While the national commemorations in Tokyo—particularly the Ceremony of Remembrance for the War Dead held at Budokan Hall in the presence of the Emperor, Empress and leading politicians—attracts most national attention, there are a multitude of locally organized events. Television news, both national and local, will give round-ups in their 15 August bulletins, and the major local ceremonies make the regional press. For example, Kushiro has a 15 August memorial ceremony organized by the city government in the Sakaemachi Peace Park, mainly for the civilian victims of the Kushiro air raids on 14-15 July 1945. On 16 August 2006 the Hokkaido Shinbun reported that this ceremony was attended by the mayor and 400 citizens. Meanwhile, a separate ceremony was held on the same day at the small Kushiro Gokoku Jinja (“Nation Protecting Shrine”) that enshrines soldiers from the city. That ceremony was attended by 600 officials and bereaved relatives.[39]

This separation of the commemoration of civilian and military victims is a conspicuous feature of Japanese war commemorations. The commemoration of “passive (civilian) victims” creates little controversy and is a cornerstone of Japanese pacifism: local commemorations such as those in Kushiro are often accompanied by municipal peace and anti-nuclear declarations. However, the commemoration of “active (military) agents” has repeatedly created controversy at home and abroad. The commemorations focus on the “sacrifice” of Japanese soldiers, and whenever local officials attend ceremonies at prefectural or municipal Gokoku shrines, it may precipitate controversies similar to those that surround prime ministerial worship at Yasukuni Shrine. [40] For example, scholar Takahashi Tetsuya, one of the most eloquent critics of official Yasukuni worship, has called the attendance of the mayor of Asahikawa and Self Defense Forces officials at the main Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja festival (4 June is the shrine’s foundation day; 5-6 June is when the war dead are commemorated) a “more serious issue than [Prime Minister Koizumi’s] Yasukuni worship.” First, the participation of leading SDF officials at the Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja festival illustrates the shrine’s continuing close links with the Japanese military. Second, the attendance of the Asahikawa Mayor (and on previous occasions the governor of Hokkaido) constitutes official commemoration at a shrine doctrinally equivalent to and associated with Yasukuni Shrine. Whereas prime ministerial worship at Yasukuni Shrine causes great national and international controversy (including over the constitutionality of official participation in religious festivals), local civic opposition cannot generate comparable oppositional pressure, so such commemorations have been able to continue. [41]

But while the commemorations of officials and dignitaries feature prominently in the Japanese media, so too can the private commemorations of ordinary people. Here the interface of commemoration and the family becomes clearer. Amid the heightened interest precipitated by Prime Minister Koizumi’s worship at Yasukuni Shrine on 15 August 2006, a Hokkaido Shinbun article about the commemorations at Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja featured two individuals who had come to pray (sanpai). One was a doctor who had brought his young son to start his education about the importance of peace; another was a woman who had been drafted to work in a factory that was bombed during the war. She lost a number of friends in the bombing and said she comes to pray for them every year. [42]

The same article also described how a citizens’ group in Asahikawa handed out “draft papers” (akagami) to passers-by to remind people that during the war families could be separated without warning. This is an annual event that takes place in a number of other cities including Sapporo. One woman who received an akagami commented, “I had heard about receiving call up papers from my parents, but actually seeing one brings it home to you.” Her grandson, meanwhile, said “forcefully” that he never wants to go to war. This thirteen-year-old boy’s comments are indicative of the fact that, whatever the virtues or failings of the Japanese education system regarding the teaching of war history, many children know how to use the pervasive “war is bad” rhetoric from an early age.

In summary, wherever one looks concerning the topics of war memory and commemoration in contemporary Japan, family, friends and furusato are to be found affecting the ways in which Japanese people continue to look back on the Asia-Pacific War. Education at school, the cultural representation of war (particularly in museums, the press and television) and official commemorations all have an important local dimension. Furthermore, whether hearing the testimony of the war generation at school or in discussions between members of the postwar generation (such as the doctor and his son at Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja), the morals of the war are frequently worked through in an explicitly family or local context.

Dominant Narratives Versus Contested War Memories: Contrasts with Allied Nations

The importance of family and local memories is by no means unique to Japan. Nevertheless, there are various reasons why social history focusing on families, friends and furusato has assumed a particularly prominent position within Japanese public war discourses. These reasons are brought into sharp focus through comparison with memories in Allied nations, particularly the United Kingdom and United States.

In the US, UK and other Allied nations, a victorious war against nations that could easily be portrayed as aggressive has produced dominant cultural narratives of a “good war” against the evils of fascism. Such a dominant cultural narrative allows war history to play a prominent role in the formation of national identity through the media, education system, museums and official sites or ceremonies of commemoration. People today are invited to share the honor of the war generation (the “greatest generation”) as part of their shared national heritage.

The effects of a dominant narrative on survivors have been illustrated by oral historian Alistair Thomson. Thomson’s “memory biographies” of ANZAC veterans from Gallipoli demonstrate how a dominant cultural narrative reinforced by patriotic official commemorations and popular cultural forms (such as the 1981 film Gallipoli) imposes pressure on survivors to compose and narrate their memories in a way that fits the dominant legend: “stories and meanings that do not fit today’s public narrative are still silenced or marginalised, or at best resurface within a sympathetic particular public, such as a gathering of fellow radicals or an oral history interview.” [43] Such processes are also evident in World War II memories. For both the war and postwar generations in the UK and US, using family, local or other identities to challenge national views of war history is risky given the widely believed and morally comfortable dominant legend. In this situation, family and local identities tend to play a supporting role to the dominant legend in national discourses and are used primarily to add nuance to rather than challenge national history.

The risk of challenging the dominant legend is clarified by observing the difficulty of portraying any Allied war actions as atrocity. In his arresting memoir, With the Old Breed, Eugene Sledge describes a horrific incident in which an American marine slashes open the cheeks of a wounded Japanese soldier so he can extract teeth as a souvenir. Eventually another marine shoots the Japanese soldier to “put him out of his misery”. [44] Such brutally frank accounts of Allied atrocity are rare. Even rarer are occasions when such admissions are made for the specific purpose of assuming individual and collective guilt, which is precisely the motivation of most Japanese soldiers who have described atrocities both in public and private. This American atrocity is the equivalent of any individual act of barbarity committed by Japanese soldiers, but Sledge merely comments, “Such was the incredible cruelty that decent men could commit when reduced to a brutish existence in their fight for survival amid the violent death, terror, tension, fatigue, and filth that was the infantryman’s war.” [45]

“Decent men in a brutal situation” is the catch-all opt-out for Allied war crimes and atrocities, from the act of an individual all the way up to the most ethically suspect of Allied strategies, particularly fire- and atomic-bombing. The BBC History Magazine gave another example in a feature article from its March 2007 issue, in which Patrick Bishop argued Bomber Command’s raids against German cities were a case of “Good men doing an ugly job”. [46] For those who challenge the “decency” in some Allied actions, veterans in particular have another ace up their sleeves: “people who were not there cannot judge.” For example, renowned World War I scholar Paul Fussell, himself a World War II veteran, wrote in his introduction to Sledge’s book, “If you are back only a couple of hundred yards behind anger and cruelty and hysteria and fear of death, you are too far back to understand, and that is one of the reasons Sledge has written this book.” [47]

The authority to speak bestowed by firsthand experience, particularly in the context of the dominant “good war” narrative, means that the postwar generations in Allied nations have found it very difficult to counter the views of those who were actually there. Nevertheless, the “good men doing an ugly job” view is problematic on two important levels. First, the moral reasoning applied to “oneself” is not applied to “others.” Japanese atrocities (or German bombing) are very rarely, if ever, judged to be the acts of “good men doing an ugly job” in accounts published by American or British commentators. In an analytical double-standard, while Allied atrocities are a result of what war does to “decent men,” Japanese atrocities are typically treated as an illustration of the barbarity of Japanese soldiers consonant with the goals and policies of the Japanese state. Second, following on from the previous point, if the moral reasoning of “good men doing an ugly job” is applied to Japanese soldiers, it becomes effectively the same moral logic used by Japanese nationalists, who wish to downplay or dismiss Japanese war guilt.

Understanding the mechanisms of the Allied “good war” narrative, therefore, is actually very helpful for understanding Japanese nationalistic defenses of Japan’s seemingly indefensible war conduct. Japanese nationalists promote a “good war” narrative of the Greater East Asian War based on the aim or achievement of the “liberation of Asia from Western colonialism.” According to nationalists, Japanese soldiers were good men in difficult circumstances and even if their actions had been brutal, they were an inevitable result of the extreme circumstances, or, as in the case of Ito Yoshimitsu whose story started this essay, their actions were misunderstood and unfairly judged following Japan’s defeat. As in Allied nations, within Japanese nationalist historical consciousness family and local history are of value only insofar as they reinforce the “good war” narrative. Testimony that contradicts the “good war” narrative is a threat and an affront to national honor. In Allied nations the strength of the dominant narrative is usually sufficient to marginalize oppositional voices, but with a significant section of Japanese society accepting the view that Japan fought an aggressive war, nationalists in Japan must resort to cruder tactics: discrediting witnesses, waging campaigns (such as the ongoing battles for more patriotic textbooks and education) or even intimidation of conscientious Japanese.

Despite the seductive nature of the nationalist narrative that assigns all guilt to the Western powers, for many Japanese people the evidence of the Japanese military’s conduct and their own suffering both in battle and on the home front precludes positive identification with the wartime state. In this situation, the political ideology, gender, or family and local identities that are marginalized in dominant national narratives come to the fore because they offer people ways to separate their own actions and experiences from those of the wartime state. The “self-other” dyad assumes the following form: while the militarist/state “other” aggressed, the family/local “self” suffered, was coerced into compliance, or was powerless to prevent Japan’s aggression/fate. For those individuals brave enough to issue public confessions of guilt, a strong sense of moral or political purpose is usually necessary to proffer such a bold challenge to national conduct and official obfuscations of Japanese war responsibility.

Overall, in Japan there is no dominant national narrative to subsume the rich variety of individual and family experiences into a generic, flattened out collective narrative. The government promotes a fragile and unconvincing compromise that Japan did not, or did not intend, to fight an “aggressive war”, although it admits “aggressive acts” (the significance of this is discussed below). This stance is criticized internationally as inadequate, and domestically from both the Japanese political right and political left (either for being “masochistic” and “acknowledging Japanese aggression too much,” or for not going far enough to address war responsibility issues).

Given Japan’s contested war memories, family and local narratives cannot be repressed in the public domain by a dominant narrative (although other factors—such as guilty secrets, reluctance to become embroiled in controversy or the inability to articulate painful memories—are significant issues). As Petra Buchholz has noted, Japan has a particularly vibrant literature of autobiography and self-history, and while much of this is civilian testimony, the Japanese war literature is also noteworthy for the proliferation of soldier memoirs. [48] The inability to settle on a dominant narrative at a national level and the benefits for many of framing war history in terms other than national history is, I would argue, a key if not the key reason for the proliferation of testimony and memories framed in family and local terms in contemporary Japan.

The roles of family, friends (particularly veterans’ groups, or sen’yu, literally “war friends”) and furusato are also evident in the most important forms of official war commemoration. As was illustrated in the example of Kushiro above, civilian victims and the military war dead tend to be commemorated separately. Overall, Japanese commemorations exhibit three other key features. First, civilian victims tend to be commemorated locally; second, the main commemorations for the military dead are national, but there are also local commemorations; and third, it is bereaved relatives rather than veterans who are the most politically-influential interest group in contemporary Japan.

Across the country most official commemorations of civilian victims are organized at a local level, the events are relatively low-profile, and they are attended by only a few dozen or few hundred survivors and bereaved relatives. By contrast, the commemorations in Hiroshima, Nagasaki and Okinawa have assumed quasi-national status, are broadcast on national television, and are now routinely attended by senior politicians.

Most commemorations of civilians are organized locally because official commemoration of civilian victims at a national level poses a dilemma. Given that the state failed to protect its civilians in the homeland and colonies, the national government might not be considered the ideal leader of official mourning. National commemoration of civilian victims could easily drag the state into ritualized apologies to its own people, and thereby undermine the state’s authority. The risk of this occurring becomes more evident when one considers that a number of victims’ groups, from hibakusha (A-bomb victims) to zanryu koji (war orphans left behind in China), have blamed the Japanese government for their plights and sued the government for more assistance.

A further reason for local commemorations is the spiritual and political significance of “sites of memory.” For example, holding the official commemorations of the A-bombs away from the hypocenters (“ground zero”) in Hiroshima and Nagasaki is unthinkable. With sites such as the Hiroshima museum and peace park funded by local taxes and administered by local officials, local government inevitably takes the leading role in any commemorations on those sites.

The fact that the ceremonies are local also allows for more latitude in official apologies and peace declarations. In Hiroshima, for example, the local government (unlike the military or national government) can separate itself from responsibility for what happened on 6 August 1945 and therefore lead local mourning. Furthermore, as issues of “Hiroshima’s war guilt” do not overshadow the ceremony (although Hiroshima’s military role and the presence of forced laborers is briefly acknowledged in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum’s exhibits), the “state aggressed-local people suffered” framework can be and is employed by local officials. Consequently, local governments such as in Hiroshima and Nagasaki frequently offer more forthright official apologies for Japanese aggression (or criticisms of key allies such as the US over military/nuclear policy) than the national government. In 1995, for example, the straightforward “official” apology to Asian nations from Hiroshima Mayor Hiraoka Takashi at the peace ceremony on 6 August was in marked contrast to the evasive and shambolic 9 June 1995 Diet Resolution to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war or Prime Minister Murayama’s sincere but “private” apology on 15 August 1995 in the Murayama communique (danwa). [49]

The significance of these regional commemorations of war victimhood in Japan are even more pronounced when one considers their equivalents in the UK and US. Comparisons with the US in particular are not easy given that fighting barely came to the American homelands (Pearl Harbor comes under military not civilian commemorations), but the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaigns during the Battle of Britain and throughout the war that claimed the lives of around 60,000 British civilians are not remembered using the somber rhetoric of victimhood and the preciousness of peace. In Britain’s case, the Blitz has been remembered (with the help of much myth-making [50]) primarily as an example of British pluck and courage in the nation’s “darkest hour.” The moral is not the terrible nature of war: Germany’s indiscriminate targeting of British civilians forms part of the rationale for the necessity of the “good war” to defeat Nazi Germany.

The second feature of Japanese commemorations relates to commemoration of the military war dead, which also offers different dilemmas for Japan in comparison to the UK and US. However problematic the conduct of the Japanese wartime state and military, the contemporary Japanese state still feels obliged to at least thank and offer condolences to those that the state called on to fight and die for their country. Herein lies the significance of the term “aggressive acts” (shinryaku koi) rather than “aggressive war” (shiryaku senso) in official apologies and statements about Japanese responsibility. “Aggressive acts,” in other words atrocities, can be blamed on poor leadership, mistakes, the heat of battle, or simply the cruel nature of war. But “aggressive war” is a blanket condemnation of Japan’s entire war and even the foundations of the Japanese empire. The state cannot admit that Japan fought an aggressive war without criminalizing all Japanese war actions and thereby delegitimizing the “sacrifice” of the war dead. As long as the state feels obliged to thank rather than apologize to its service personnel, references to aggressive war are anathema. This also goes a long way to explaining why the Japanese government has sought, where possible, to limit mentions of Japanese aggression in Japanese textbooks through its screening process.

A group that has played a leading role in pressing the government to avoid admitting an aggressive war is the War Bereaved Association (Nippon Izokukai). But as Franziska Seraphim’s recent and illuminating account of the history of the Izokukai reveals, the Izokukai’s conservative interpretation of war history was never actively endorsed by all members of the organization. Many members appreciated more the “organized assistance for personal remembrance” (such as bus tours to commemorative sites including Yasukuni Shrine), the social network of people with similar experiences, and the benefits of collective bargaining over pension rights with the government. [51] In particular, the issue of official prime ministerial worship divided the Izokukai after the enshrinement of 14 class A war criminals in 1978. The Yasukuni issue led to the breakaway of a number of local chapters in the early 1980s and the formation of the National Association of the War Bereaved Families for Peace (Heiwa Izokukai Zenkoku Renrakukai) in 1986.

In a further illustration of the importance of local aspects in war-related politics, the breakaway started with a local dispute in Hokkaido. In 1982, the Asahikawa City Kamui District War Bereaved Association left the national organization following a request by the Hokkaido Rengo Izokukai for 12,000 yen from each household receiving a bereaved family pension to support the Izokukai’s campaigns for official Yasukuni Shrine worship. A dispute ensued when the Kamui branch insisted that such contributions should be voluntary. The dispute was resolved by the withdrawal of the Kamui branch from the national organization. The local branch in Takikawa (on the main route between Asahikawa and Sapporo) followed suit, and after Prime Minister Nakasone’s official Yasukuni worship in 1985, a number of other local chapters across Japan left in protest, too. [52] The Bereaved Families for Peace were critical of Yasukuni worship and promoted critical consciousness of Japan’s aggressive war (shinryaku senso), but in severing their ties to the central organization they were never able to achieve the political muscle of the national organization.

Despite such fractions, the Izokukai has remained a key interest group in war-related politics. It has supported the LDP throughout the postwar, delivering a significant bloc of votes during general elections in return for welfare and pension rights for veterans and bereaved families that continue to this day. The activities and political muscle of the War Bereaved Association illustrate the third conspicuous feature of Japanese commemorations: whereas the most politically powerful groups representing the war generation in the UK and US tend to be veterans’ associations, in Japan the War Bereaved Association plays this role.

In the UK and US, official commemorations are patriotic occasions to thank the war generation for their sacrifice. Veterans have pride of place at the key ceremonies on Remembrance Sunday in the UK or Veterans’ Day in the US. In Japan, by contrast, veterans play a small or marginal role in official 15 August commemorations. Walking around Yasukuni Shrine on 15 August one can see many groups of veterans bussed in to pray for the souls of their fallen comrades, but the key state-sponsored commemorations take place across the road in Budokan Hall. There, the central role of bereaved families can be seen in the approximately six thousand other participants, most of whom are relatives of soldiers who died in the war. The commemorations are somber and since 1993 have also been the stage for a prime ministerial acknowledgement of the damage and suffering caused by the Japanese military throughout Asia. Condolences are offered to all victims of the war across Asia, a custom that complicates any moves to incorporate a greater role for veterans at these commemorations.

Overall, the prominence of bereaved relatives rather than veterans in Japan’s major state-sponsored annual commemorations, the somber rather than jingoistic nature of commemorations, and the need to proffer some form of acknowledgement of sufferings in other countries all speak volumes for the legacies of defeat and war responsibility. So does the fallout from any attempts by Japanese officials to move towards Anglo-American-style patriotic celebrations of veterans and the war dead. The key commemorative sites for fallen soldiers are Yasukuni Shrine and its “branch shrines,” the Gokoku (“Nation Protecting”) Shrines that exist in every prefecture (described in note [14]). Yasukuni Shrine enshrines 2.46 million individuals who died in the service of Japan since 1868 (86.5 per cent of whom died during the “Greater East Asian War”, 1941-5) and presents a “good war,” unapologetic war narrative in its museum, Yushukan. Since 1985, however, any visits by Japanese prime ministers, whether “private” or “official”, have precipitated a furious reaction in neighboring countries, notably China and South Korea, and divided Japanese public opinion almost down the middle.

In sum, even at the national or official levels of war memories and commemoration, family, friends and furusato have their role to play. Commemorations of civilian victims are managed primarily at the local level, while bereaved families have taken center stage at military commemorations. The War Bereaved Association representing families of the war dead is a particularly powerful lobby group, but it has been divided and even faced breakaways by local chapters over issues of war responsibility and Yasukuni Shrine worship. These issues are all brought into sharp contrast with the equivalent situations in the UK and US and reveal just how deeply issues of war responsibility continue to ensure the ongoing importance of family, friends and furusato within official commemorations in Japan today. The comparative approach reveals that the more contested the war memories are within a nation, the more that family, friends and furusato assume importance within the processes of cultural remembering and official commemoration.

Conclusions

This article has focused on the often overlooked point that a deep understanding of war memories, Japanese or others’, requires incorporating all aspects of people’s identities. In Japan’s case, whether in the testimony of the war generation, the development of collective narratives or the practices of national and official commemorations, family, friends and furusato all play important roles. They are not the only powerful sources of identity pertinent to Japanese war debates and this essay could equally have been written with regard to gendered, political or generation identities. The key conclusion, however, is that only by examining all aspects of Japanese people’s multilayered and situational identities can the diversity of interpretations of war history within Japan’s contested war memories be explained.

But perhaps more importantly, focusing on the issues “closest to home” reveals the “human side” of us all. Given that stereotypes in peacetime and atrocities in wartime are in part the product of the dehumanization and arbitrary categorizations of others whipped up by self-righteous nationalism, the attempt in this essay to shift the focus of attention from simply “people as members of a nation” to people as diverse individuals with families, friends and hometowns as well as nationalities can contribute to promoting peace and reconciliation within Asia and beyond. While the focus of this essay has been on understanding Japanese views, and in particular the views of people from Hokkaido, the central lessons apply to all nations. The “history issue” in Asia would take a large step towards being resolved if Chinese, Koreans and others could be seen more by the Japanese not simply as Chinese or Korean “others” but as individuals, members of families, friends and members of local communities that all have their own often harrowing stories to tell of how the Japanese military affected their lives during World War II. Similarly, can we envisage a day when Chinese, Koreans and other victims of Japanese colonialism and war recognize the multiple wartime experiences of the Japanese people, including those of assailants, but also victims?

Acknowledgements:

This essay is part of a project called “War and Memory in Hokkaido: a case study in the regional remembering of World War II,” which is supported by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education. This article was written for Japan Focus and posted on July 10, 2007. I would like to thank Mark Selden, Richard Minear and Sabine Fruhstuck for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

References

[1] Kakiuchi Toshio, Sokoku ni inochi sasagete (Giving One’s Life to One’s Country), (Kyobunsha 1988), p. 135.

[2] Ibid. p.21. Ito’s last will and testament is representative of a number of B and C class war criminals whose last words were collected in Testaments of the Century. See John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (W.W. Norton & Co. 1999), pp. 508-21.

[3] Kakiuchi, Sokoku, pp. 57-8.

[4] Ibid. 337-8.

[5] For development of my critiques of the “orthodoxy” within the English-language media and academy, see Philip Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories: The ‘Memory Rifts’ in Historical Consciousness of World War II (Routledge 2007), especially the Introduction and Appendix. See also “Reporting the 2001 textbook and Yasukuni Shrine controversies: Japanese war memory and commemoration in the British media”, Japan Forum (2005) Vol. 17.3, pp. 287-309.

[6] Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories, pp. 20-28.

[7] Ibid., pp. 17-18. My use of the term “composure” is informed by Alistair Thomson: “‘Composure’ is an aptly ambiguous term to describe the process of memory making. In one sense we compose or construct memories using the public languages and meanings of our culture. In another sense we compose memories that help us to feel relatively comfortable with our lives and identities, that give us a feeling of composure.” Alistair Thomson, ANZAC Memories: Living with the Legend (Oxford University Press 1994), p. 8.

[8] Philip Seaton, “Reporting the ‘comfort women’ issue, 1992-3: Japan’s contested war memories in the national press”, Japanese Studies (2006) Vol. 26.1, pp. 99-112.

[9] Nishida Hideko, “Senjika Hokkaido ni okeru chosenjin ‘romu ianfu’ no seiritsu to jitsuno” (“‘Laborer comfort women’ from Korea in wartime Hokkaido”), Joseishi kenkyu Hokkaido, (August 2003), pp. 16-36. There were about 100 Korean women working in the sex industry in Hokkaido at the beginning of 1938. The establishment of “comfort stations” near mines was officially intended to “prevent laborers running away” but it was also a means to control sexually transmitted disease. Korean women also worked in cafes and bars, although the local police’s insistence on health checks for workers indicates that such establishments were viewed as “dens of sexually transmitted disease.” Nishida’s survey, based on company documents and the national survey in 1940 (as yet no survivors have come forward to testify), revealed that 333 Korean women, some as young as 14, worked in the entertainment industry in Hokkaido, while around 90 worked in 17 “comfort stations” attached to coal mines. Nishida concludes their experiences exemplify the state’s “double policy of oppression” against both Koreans and women.

[10] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (Verso 1983).

[11] Hokkaido Shinbun (ed) Senka no kioku: sengo rokuju nen, hyaku-nin no shogen (Memories of the War: 100 People’s Testimony 60 Years On), (Hokkaido Shinbunsha 2005), pp. 267-8. This book is available online (including photographs of the people who told their stories). Miyamoto’s testimony is here.

[12] Ibid. pp. 230-1. Available online.

[13] Ibid. pp. 198-201. Available online.

[14] Following the Meiji Restoration, the government ordered the establishment of Shokonjo or Shokonsha (“place/shrine to invite the souls of the dead”) to commemorate those who had given their lives for the state. Tokyo Shokonsha became Yasukuni Shrine in 1879. In 1939 Shokonsha were renamed Gokoku Jinja (“nation protecting shrine”) and at least one was officially designated in each prefecture to commemorate soldiers from that prefecture. Hokkaido has three designated Gokoku Jinja: in Asahikawa, Sapporo and Hakodate. Other non-designated Gokoku Jinja exist, including in Kushiro (mentioned later in the essay). These shrines, like Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, commemorate those that died in the service of the Japanese military (gunjin) or those attached to the military (gunzoku), such as nurses. People may be commemorated simultaneously at Yasukuni Shrine and their local Gokoku Jinja. Similar to Yasukuni, the shrines became autonomous religious organizations after Japan’s defeat. They have annual festivals specifically to commemorate the war dead but also become a focal point for commemorations on 15 August. While officially separate organizations, the Gokoku Jinja are all part of the Association of Shinto Shrines (Jinja Honcho), and the head priest of Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja, Shionoya Tsuneya, told me during an interview (1 March 2007) that he attended annual gatherings with other head priests of Gokoku Jinja at Yasukuni Shrine. See John Nelson, “Social Memory as Ritual Practice: Commemorating Spirits of the Military Dead at Yasukuni Shrine”, The Journal of Asian Studies (2003), Vol. 62.2, pp. 443-467.

See also the Hokkaido Gokoku Jinja webpage.

[15] Itoman City (eds), Itoman-shi ni okeru Okinawasen no taikenkishu (A Collection of Testimony about the Battle for Okinawa in Itoman City), (Itoman City 1995), p. 149.

[16] Ibid. 156, 159.

[17] Ibid. 160.

[18] The museum has a webpage.

[19] Tanaka Yuki, “Japan’s Kamikaze Pilots and Contemporary Suicide Bombers: War and Terror”, Japan Focus.

[20] Families in Japan often own a plot of land where the remains of family members are buried and memorial stones are erected to deceased family members. Maeda would not need to be buried there because his body would be lost in the kamikaze attack, but in the same way that soldiers would say “Let’s meet again at Yasukuni” (referring to their souls being enshrined together at Yasukuni Shrine), Maeda’s soul could rest with his mother’s in the family grave. As the television news report (discussed later) about the play based on Maeda’s life illustrated, his family did erect a memorial stone to him where relatives continue to pray for his soul.

[21] Muranaga Kaoru (ed), Chiran Tokubetsu Kogekitai (The Kamikaze of Chiran), (Japuran 1989), pp.58-9.

[22] Hokkaido Shinbun, Senka no Kioku, p. 210. Available online.

[23] Philip Seaton, “Do you really want to know what your uncle did? Coming to terms with relatives’ war actions in Japan”, Oral History (2006) Vol. 43.1, pp. 53-60.

[24] Sapporo Kyodo wo Horu Kai, Senso wo horu: Shogen, kagai to higai, Chugoku kara tonan Ajia e (Unearthing the War: Perpetrator and Victim Testimony from China to Southeast Asia), (Sapporo Kyodo wo Horu Kai 1995), pp. 246-7.

[25] Ibid. p. 251. Tanifuji’s testimony contains all the hallmarks of members of the Chinese Returnees Association (Chukiren). Chukiren members were interned at Fushun prison in China until 1956 before returning home and becoming one of the most active groups of Japanese soldiers confessing to atrocities. However, Tanifuji does not explicitly state that he is a member of this group.

[26] Linda Hoaglund, “Stubborn Legacies of War: Japanese Devils in Sarajevo”, Japan Focus

[27] Kurahashi Ayako, Kempei datta chichi no nokoshita mono (What my Military Policeman Father Left Me), (Kobunken 2002), p. 109. Azuma’s story is also told in Ian Buruma, Wages of Guilt, Memories of War in Germany and Japan (Vintage 1995), pp. 129-34.

[28] Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (Vintage 1994), Chapter 2.

[29] For themes of racism in World War II atrocities, see John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon Books 1986).

[30] Kayano Shigeru (trans. Kyoko Selden and Lili Selden), Our Land Was a Forest: An Ainu Memoir (Westview Press 1994), pp. 79-86.

[31] Thomson, ANZAC Memories, p. 12. The full citation is: “My argument is that an official or dominant legend works not by excluding contradictory versions of experience, but by representing them in ways that fit the legend and flatten out the contradictions, but which are still resonant for a wide variety of people.”

[32] Hokkaido Shinbun, Senka no kioku, p. 222.

[33] There is a vast literature on the textbook issue throughout the postwar. Two essays that give a good overview of the twists and turns are: Caroline Rose, “The Battle for Hearts and Minds: Patriotic Education in Japan in the 1990s and Beyond” in Naoko Shimazu (ed) Nationalisms in Japan (Routledge 2006); and Nozaki Yoshiko and Inokuchi Hiromitsu, “Japanese Education, Nationalism, and Ienaga Saburo’s Textbook Lawsuits” in Laura Hein and Mark Selden (eds) Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany, and the United States (M.E. Sharpe 2000).

[34] Historical Museum of Hokkaido (see webpage). The English is an accurate translation of the Japanese panel, barring the last sentence, which in the original Japanese makes it much clearer that the lives lost were of forced laborers.

[35] Historical Museum of Hokkaido, From Recession to World War II (Sixth Exhibition Hall Guidebook), (HMH 2000). Forced labor is on pages 42 and 44, air raids are on page 48.

[36] I am grateful to Ikeda Takao of the Historical Museum of Hokkaido for compiling this data.

[37] Hokkaido Shinbun, “Heiwa no imi, kosei ni” (Explaining the meaning of peace to future generations), 14 July 2006 (Kushiro/Nemuro morning edition).

[38] NHK, “Hokkaido Close-up: Machi ni hodan ga uchikomareta: shogen Muroran kanpo shageki” (When shells fell on the town: testimony of the naval bombardment of Muroran), broadcast 29 July 2005.

[39] Hokkaido Shinbun, “Senka nai sekai wo” (Create a world without war), 16 August 2006 (Kushiro/Nemuro morning edition).

[40] For discussion of domestic Japanese debate over official Yasukuni Shrine worship, see Philip Seaton, “Pledge Fulfilled: Prime Minister Koizumi’s Yasukuni Worship and the Japanese Media, 2001-6” in John Breen (ed) Yasukuni: Contested Meanings (Hurst & Co., forthcoming).

[41] Hokkaido Shinbun, “Gokoku jinja reitaisai, shicho no sanretsu hihan, Asahikawa de seikyo bunri shukai” (Gokoku Shrine festival, Mayor’s attendance criticized, meeting in Asahikawa about the constitutional separation of religion and the state), 7 June 2005. Takahashi Tetsuya, personal correspondence, 30 June 2007.

[42] Hokkaido Shinbun, “Heiwa no totosa hishihishi” (The Preciousness of Peace), 16 August 2006 (Asahikawa morning edition).

[43] Thomson, ANZAC Memories, p. 215.

[44] E.B. Sledge, With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa (Oxford University Press 1990), p. 120.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Patrick Bishop, “Bomber Boys”, BBC History Magazine March 2007, pp. 14-19.

[47] Paul Fussell, “Introduction” in Sledge, With the Old Breed, p. xvi.

[48] Petra Buchholz, “Tales of War: autobiographies and private memories in Japan and Germany”, online.

[49] Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories, pp. 57, 94-6.

[50] See Angus Calder, The Myth of the Blitz (Pimlico 1991). Rather than focusing solely on the “courage and pluck” of the British people, Calder’s account also documents conscientious objectors to Britain’s war against Germany, class enmity between evacuated Londoners and their rural hosts, and the booing of Churchill and the royal family.

[51] Franziska Seraphim, War Memory and Social Politics in Japan, 1945-2005, (Harvard University Press 2007), Chapter 2, especially p. 84. Regarding pension rights secured by the Izokukai, Gavan McCormack states that in the early 1990s the Japanese government was paying more money per year in pensions to veterans and their survivors than had been paid in total to neighboring countries as compensation. The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence (M.E. Sharpe 1996), p. 245.

[52] Tanaka Nobumasa, Tanaka Hiroshi & Hata Nagami, Izoku to sengo (Bereaved Families and the Postwar) (Iwanami Shinsho 1995), pp. 152-5.