America’s Afghanistan: The National Security and a Heroin-Ravaged State [Russian translation available.

Peter Dale Scott

For several years, informed observers independent of the national security bureaucracy have called for terminating current specific American policies and tactics in Afghanistan– many reminiscent of the US in Vietnam.

Informed observers decry the use of air strikes to decapitate the Taliban and al Qaeda, an approach that has repeatedly resulted in the death of civilians. Many counsel against the insertion of more and more US and other foreign troops, as pursued first by the Bush administration and then, even more vigorously, in the early days of the Obama administration, in an effort to secure the safety and allegiance of the population. And they regret the on-going interference in the fragile Afghan and Pakistan political processes, in order to secure outcomes desired in Washington.1 A New York Times headline, “In Pakistan, US Courts Leader of Opposition,” was barely noticed in the U.S. mainstream media.

One root source of official myopia will not be addressed soon – the conduct of crucial decision-making in secrecy, not by those who know the area, but by those skilled enough in bureaucratic politics to have earned the highest security clearances. It may nevertheless be productive to criticize the mindset shared by the decision-makers, and to point out elements of the false consciousness which frames it, and which will require correction if the US is not to wade deeper into its Afghan quagmire.

Why One Should Think of So-Called “Failed States” as “Ravaged States”

I have in mind the bureaucratically convenient concept of Afghanistan as a failed or failing state. This epithet has been frequently applied to Afghanistan since 9/11, 2001, and also to other areas where the United States is eager or at least contemplating intervention – such as Somalia, and the Congo. The concept conveniently suggests that the problem is local, and requires outside assistance from other more successful and benevolent states. In this respect, the term “failed state” stands in the place of the now discredited term “undeveloped country,” with its similar implication that there was a defect in any such country to be remedied by the “developed” western nations.

A Failed States Index

Most outside experts would agree that the states commonly looked on as “failed,” — notably Afghanistan, but also Somalia or the Democratic Republic of the Congo – share a different feature. It is better to think of them not as failed states but as ravaged states, ravaged primarily from the intrusions of outside powers. The policy implications of recognizing that a state has been ravaged are complex and ambiguous. Some might see past abuses in such a state as an argument against any outside involvement whatsoever. Others might see a duty for continued intervention, but only by using different methods, in order to compensate for the damage already inflicted.

The past ravaging of Somalia and the Congo (formerly Zaire) is now indisputable. These two former colonies were among the most ruthlessly exploited of any in Africa by their European invaders. In the course of this exploitation, their social structures were systematically uprooted and never replaced by anything viable. Thus they are best understood as ravaged states, using the word “state” here in its most generic sense.

But the word “state” itself is problematic, when applied to the arbitrary divisions of Africa agreed on by European powers for their own purposes in the 19th century. Many of the straight lines overriding the tribal entities of Africa and separating them into colonies were established by European powers at a Berlin conference in 1884-85.2 Our loosest dictionary definition of “state” is “body politic,” implying an organic coherence which most of these entities have never possessed. The great powers played similar games in Asia, which are still causing misery in areas like the Shan states of Myanmar, or the tribes of West Papua.

Still less can African states be considered modern states as defined by Max Weber, when he wrote that the modern state “successfully upholds a claim on the monopoly of the legitimate use of violence [Gewaltmonopol] in the enforcement of its order.”3 The Congo in particular has been so devoid of any state features in its past history that it might be better to think of it as a ravaged area, not even as a ravaged state.

The Historical Ravaging of Afghanistan

Afghanistan in contrast can be called a state, because of its past history as a kingdom, albeit one combining diverse peoples and languages on both sides of the forbidding Hindu Kush. But almost from the outset of that Durrani kingdom in the 18th century, Afghanistan too was a state ravaged by foreign interests. Even though technically Afghanistan was never a colony, Afghanistan’s rulers were alternatively propped up and then deposed by Britain and Russia, who were competing for influence in an area they agreed to recognize as a glacis or neutral area between them.

Such social stability as there existed in the Durrani Afghan kingdom, a loose coalition of tribal leaders, was the product of tolerance and circumspection, the opposite of a monopolistic imposition of central power. A symptom of this dispersion of power was the inability of anyone to build railways inside Afghanistan – one of the major aspects of nation building in neighboring countries.4

The British, fearing Russian influence in Afghanistan, persistently interfered with this equilibrium of tolerance. This was notably the case with the British foray of 1839, in which their 12,000-man army was completely annihilated except for one doctor. The British claimed to be supporting the claim of one Durrani family member, Shuja Shah, an anglophile whom they brought back from exile in India. With the disastrous British retreat in 1842, Shuja Shah was assassinated.

The social fabric of Afghanistan, with a complex tribal network, was badly disrupted by such interventions. Particularly after World War II, the Cold War widened the gap between Kabul and the countryside. Afghan cities moved towards a more western urban culture, as successive generations of bureaucrats were trained elsewhere, many of them in Moscow. They thus became progressively more alienated from the Afghan rural areas, which they were trained to regard as reactionary, uncivilized, and outdated.

Meanwhile, especially after 1980, moderate Sufi leaders in the countryside were progressively displaced in favor of radical jihadist Islamist leaders, thanks to massive funding from agents of the Pakistani ISI, dispersing funds that came in fact from Saudi Arabia and the United States. Already in the 1970s, as oil profits skyrocketed, representatives of the Muslim Brotherhood and the Muslim World League, with Iranian and CIA support, “arrived on the Afghan scene with bulging bankrolls.”5 Thus the inevitable civil war that ensued in 1978, and led to the Soviet invasion of 1980, can be attributed chiefly to Cold War forces outside Afghanistan itself.

Russian forces in Afghanistan

Afghanistan was torn apart by this foreign-inspired conflict in the 1980s. It is being torn apart again by the American military presence today. Although Americans were initially well received by many Afghans when they first arrived in 2001, the U.S. military campaign has driven more and more to support the Taliban. According to a February 2009 ABC poll, only 18 percent of Afghanis support more US troops in their country.

Thus it is important to recognize that Afghanistan is a state ravaged by external forces, and not just think of it as a failing one.

The Foreign Origins of the Forces Ravaging Afghanistan Today: Jihadi Salafist Islamism and Heroin

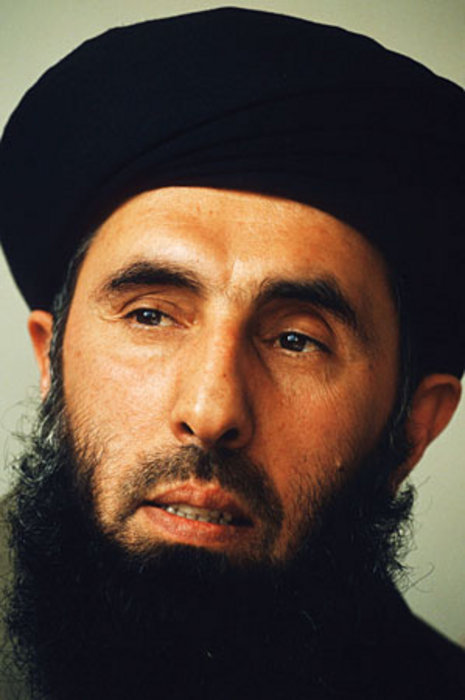

These external forces include the staggering rise of both jihadi salafism and opium production in Afghanistan, following the interventions there two decades ago by the United States and the Soviet Union. In dispersing US and Saudi funds to the Afghan resistance, the ISI gave half of the funds it dispersed to two marginal fundamentalist groups, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and Abdul Razul Sayyaf, which it knew it could control – precisely because they lacked popular support.6 The popularly based resistance groups, organized on tribal lines, were hostile to this jihadi salafist influence: they were “repelled by fundamentalist demands for the abolition of the tribal structure as incompatible with [the salafist] conception of a centralized Islamic state.7

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar

Meanwhile, Hekmatyar, with ISI and CIA protection, began immediately to compensate for his lack of popular support by developing an international traffic in opium and heroin, not on his own, however, but with ISI and foreign assistance. After Pakistan banned opium cultivation in February 1979 and Iran followed suit in April, the Pashtun areas of Pakistan and Afghanistan ‘‘attracted Western drug cartels and ‘scientists’ (including ‘some “fortune-seekers” from Europe and the US’) to establish heroin processing facilities in the tribal belt.8

Heroin labs had opened in the North-West Frontier province by 1979 (a fact duly noted by the Canadian Maclean’s Magazine of April 30, 1979). According to Alfred McCoy, “By 1980 Pakistan-Afghan opium dominated the European market and supplied 60 percent of America’s illicit demand as well.”9 McCoy also records that Gulbuddin Hekmatyar controlled a complex of six heroin laboratories in a region of Baluchistan “where the ISI was in total control.”10

The global epidemic of Afghan heroin, in other words, was not generated by Afghanistan, but was inflicted on Afghanistan by outside forces.11 It remains true today that although 90 percent of the world’s heroin comes from Afghanistan, the Afghan share of proceeds from the global heroin network, in dollar terms, is only about ten percent of the whole.

Afghan opium

In 2007, Afghanistan supplied 93% of the world’s opium, according to the U.S. State Department. Illicit poppy production, meanwhile, brings $4 billion into Afghanistan,12 or more than half the country’s total economy of $7.5 billion, according to the United Nations Office of Drug Control (UNODC).13 It also represents about half of the economy of Pakistan, and of the ISI in particular.14

Destroying the labs has always been an obvious option, but for years America refused to do so for political reasons. In 2001 the Taliban and bin Laden were estimated by the CIA to be earning up to 10 per cent of Afghanistan’s drug revenues, then estimated at between 6.5 and 10 billion U.S. dollars a year.15 This income of perhaps $1 billion was less than that earned by Pakistan’s intelligence agency ISI, parts of which had become the key to the drug trade in Central Asia. The UN Drug Control Program (UNDCP) estimated in 1999 that the ISI made around $2.5 billion annually from the sale of illegal drugs.16

At the start of the U.S. offensive in 2001, according to Ahmed Rashid, “The Pentagon had a list of twenty-five or more drug labs and warehouses in Afghanistan but refused to bomb them because some belonged to the CIA’s new NA [Northern Alliance] allies.”17 Rashid was “told by UNODC officials that the Americans knew far more about the drug labs than they claimed to know, and the failure to bomb them was a major setback to the counter-narcotics effort.”18

James Risen reports that the ongoing refusal to pursue the targeted drug labs came from neocons at the top of America’s national security bureaucracy, including Douglas Feith, Paul Wolfowitz, Zalmay Khalilzad, and their patron Donald Rumsfeld.19 These men were perpetuating a pattern of drug-traffic protection in Washington that dates back to World War Two.20

There were humanitarian as well as political reasons for tolerating the drug economy in 2001. Without it that winter many Afghans would have faced starvation. But the CIA had mounted its coalition against the Taliban in 2001 by recruiting and even importing drug traffickers, many of them old assets from the 1980s. An example was Haji Zaman who had retired to Dijon in France, whom “British and American officials…met with and persuaded … to return to Afghanistan.21

Thanks in large part to the CIA-backed anti-Soviet campaign of the 1980s, Afghanistan today is a drug-corrupted or heroin-ravaged society from top to bottom. On an international index measuring corruption, Afghanistan ranks as #176 out of 180 countries. (Somalia is 180th). 22 Karzai returned from America to his native country vowing to fight drugs, yet today it is recognized that his friends, family, and allies are deeply involved in the traffic.23

In 2005, for example, Drug Enforcement Administration agents found more than nine tons of opium in the office of Sher Muhammad Akhundzada, the governor of Helmand Province, and a close friend of Karzai who had accompanied him into Afghanistan in 2001 on a motorbike. The British successfully demanded that he be removed from office.24 But the news report confirming that Akhunzada had been removed announced also that he had been simultaneously given a seat in the Afghan senate.25

Former warlord and provincial governor Gul Agha Sherzai, an American favorite who recently endorsed Karzai’s re-election campaign, has also been linked to the drugs trade.26 In 2002 Gul Agha Sherzai was the go-between in an extraordinary deal between the Americans and leading trafficker Haji Bashar Noorzai, whereby the Americans agreed to tolerate Noorzai’s drug-trafficking in exchange for supplying intelligence on and arms of the Taliban.27

By 2004, according to House International Relations Committee testimony, Noorzai was smuggling two metric tons of heroin to Pakistan every eight weeks.28 Noorzai was finally arrested in New York in 2005, having come to this country at the invitation of a private intelligence firm, Rosetta Research. The U.S. media reports of his arrest did not point out that Rosetta had failed to supply Noorzai the kind of immunity usually provided by the CIA.29

(It will be interesting to see, for example, whether Noorzai will remain as free for as long as Venezuelan General Ramón Guillén Davila, chief of a CIA-created anti-drug unit in Venezuela, who in 1996 received a sealed indictment in Miami for smuggling six years earlier, with CIA approval, a ton of cocaine into the United States.30 But the United States never asked for Guillén’s extradition from Venezuela to stand trial; and in 2007, when he was arrested in Venezuela for plotting to assassinate President Hugo Chavez, his indictment was still sealed in Miami.31 According to the New York Times, “The CIA, over the objections of the Drug Enforcement Administration, approved the shipment of at least one ton of pure cocaine to Miami International Airport as a way of gathering information about the Colombian drug cartels.”32 According to the Wall Street Journal, the total amount of drugs smuggled by Gen. Guillén may have been more than 22 tons.33)

There are numerous such indications that those governing Afghanistan are likely to become involved, willingly or unwillingly, in the drug traffic. One can also probably anticipate that, with the passage of time, the Taliban will also become increasingly involved in the drug trade, just as the FARC in Colombia and the Communist Party in Myanmar have evolved in time from revolutionary movements into drug-trafficking organizations.

The situation in Pakistan is not much better. The U.S. mainstream media have never mentioned the February 23 report in the London Sunday Times and that Asif Ali Zardari, now the Pakistani Prime Minister, was once caught in a DEA drug sting. An undercover DEA informant, John Banks, told the Sunday Times that, posing as a member of the U.S. mafia, he had taped Zardari and two associates for five hours; Zardari discussed how he could ship hashish and heroin to the United States, as he had done already to Great Britain. A retired senior British customs officer confirmed that the government had received reports of Zardari’s alleged financing of the drug trade from “about three or four sources.” Banks “claimed the subsequent investigation was halted after the CIA said it did not want to destabilise Pakistan.”

Important as heroin may have become to the Afghan and Pakistani political economies, the local proceeds are only a small share of the global heroin traffic. According to the UN, the ultimate value in world markets in 2007 of Afghanistan’s $4 billion opium crop was about $110 billion: this estimate is probably too high, but even if the ultimate value was as low as $40 billion, this would mean that 90 percent of the profit was earned by forces outside of Afghanistan.34

It follows that there are many players with a much larger financial stake in the Afghan drug traffic than local Afghan drug lords, al-Qaeda, and the Taliban. Sibel Edmonds has charged that Pakistani and Turkish intelligence, working together, utilize the resources of the international networks transmitting Afghan heroin.35 In addition Edmonds “claims that the FBI was also gathering evidence against senior Pentagon officials – including household names – who were aiding foreign agents.”36 Two of these are said to be Richard Perle and Douglas Feith, former lobbyists for Turkey.37 Douglas Risen reports that, when Undersecretary of Defense, Feith argued in a White House meeting “that counter-narcotics was not part of the war on terrorism, and so Defense wanted no part of it in Afghanistan.”38

Loretta Napoleoni has argued that there is a Turkish and ISI-backed Islamist drug route of al Qaeda allies across North Central Asia, reaching from Tajikistan and Uzbekistan through Azerbaijan and Turkey to Kosovo.39 Dennis Dayle, a former top-level DEA agent in the Middle East, has corroborated the CIA interest in that region’s drug connection. I was present when he told an anti-drug conference that “In my 30-year history in the Drug Enforcement Administration and related agencies, the major targets of my investigations almost invariably turned out to be working for the CIA.”4

Above all, it has been estimated that 80 percent or more of the profits from the traffic are reaped in the countries of consumption. The UNODC Executive Director, Antonio Maria Costa, has reported that “money made in illicit drug trade has been used to keep banks afloat in the global financial crisis.”41

Expanded World Drug Production as a Product of U.S. Interventions

The truth is that since World War II the CIA, without establishment opposition, has become addicted to the use of assets who are drug-traffickers, and there is no reason to assume that they have begun to break this addiction. The devastating consequences of CIA use and protection of traffickers can be seen in the statistics of drug production, which increases where America intervenes, and also declines when American intervention ends.

Just as the indirect American intervention of 1979 was followed by an unprecedented increase in Afghan opium production, so the pattern has repeated itself since the American invasion of 2001. Opium poppy cultivation in hectares more than doubled, from a previous high of 91,000 in 1999 (reduced by the Taliban to 8,000 in 2001) to 165,000 in 2006 and 193,000 in 2007. (Though 2008 saw a reduced planting of 157,000 hectares, this was chiefly explained by previous over-production, in excess of what the world market could absorb.

No one should have been surprised by these increases: they merely repeated the dramatic increases in every other drug-producing area where America has become militarily or politically involved. This was demonstrated over and over in the 1950s, in Burma (thanks to CIA intervention, from 40 tons in 1939 to 600 tons in 1970),42 in Thailand (from 7 tons in 1939 to 200 tons in 1968) and Laos (less than 15 tons in 1939 to 50 tons in 1973).43

The most dramatic case is that of Colombia, where the intervention of U.S. troops since the late 1980s has been misleadingly justified as a part of a “war on drugs.” At a conference in 1990 I predicted that this intervention would be followed by an increase in drug production, not a reduction.44 But even I was surprised by the size of the increase that ensued. Coca production in Colombia tripled between 1991 and 1999 (from 3.8 to 12.3 thousand hectares), while the cultivation of opium poppy increased by a multiple of 5.6 (from .13 to .75 thousand hectares).45

There is no single explanation for this pattern of drug increase. But it is essential that we recognize American intervention as integral to the problem, rather than simply look to it as a solution.

It is accepted in Washington that Afghan drug production is a major source of all the problems America faces in Afghanistan today. Richard Holbrooke, now Obama’s special representative to Afghanistan and Pakistan, wrote in a 2008 Op-Ed that drugs are at the heart of America’s problems in Afghanistan, and “breaking the narco-state in Afghanistan is essential, or all else will fail.”46 It is true that, as history has shown, drugs sustain jihadi salafism, far more surely than jihadi salafism sustains drugs.47

But at present America’s government and policies are contributing to the drug traffic, and not likely to curtail it.

American Failure to Analyze the Heroin Epidemic

American policy-makers continue, however, to preserve the mindset of Afghanistan as a “failed state.” They persist in treating the drug traffic as a local Afghan problem, not as a global, still less an American one. This is true even of Holbrooke, who more than most has earned the reputation of a pragmatic realist on drug matters.

In his 2008 Op-Ed noting that “breaking the narco-state in Afghanistan is essential,” Holbrooke admitted that this will not be easy, because of the pervasiveness of today’s drug traffic, “whose dollar value equals about 50% of the country’s official gross domestic product.”48

Holbrooke excoriated America’s existing drug-eradication strategies, particular aerial spraying of poppy fields: “The … program, which costs around $1 billion a year, may be the single most ineffective policy in the history of American foreign policy….It’s not just a waste of money. It actually strengthens the Taliban and al Qaeda, as well as criminal elements within Afghanistan.”

Holbrooke and Afghan leader Karzai

Not for a moment, however, did Holbrooke acknowledge any American responsibility for the Afghan drug problem. Yet Holbrooke’s main recommendation was for “a temporary suspension of eradication in insecure areas, as part of an on-going campaign that “will take years, and … cannot be won as long as the border areas in Pakistan are havens for the Taliban and al-Qaeda.”49 He did not propose any alternative approach to the drug problem.

Washington’s perplexity about Afghan drugs became even more clear on March 27, 2009, at a press briefing by Holbrooke the morning after President Barack Obama unveiled his new Afghanistan policy.

Asked about the priority of drug fighting in the Afghanistan review, Holbrooke, as he was leaving the briefing, said “We’re going to have to rethink the drug problem. . .a complete rethink.” He noted that the policymakers who had worked on the Afghanistan review “didn’t come to a firm, final conclusion” on the opium question. “It’s just so damn complicated,” Holbrooke explained. “You can’t eliminate the whole eradication program,” he exclaimed. But that remark did make it seem that he backed an easing up of some sort. “You have to put more emphasis on the agricultural sector,” he added.50

A few days earlier Holbrooke had already indicated that he would like to divert eradication funds into funds for alternative livelihoods for farmers. But farmers are not traffickers, and Holbrooke’s renewed emphasis on them only confirms Washington’s reluctance to go after the drug traffic itself.51

According to Holbrooke, the new Obama strategy for Afghanistan would scale back the ambitions of the Bush administration to turn the country into a functioning democracy, and would concentrate instead on security and counter-terrorism.52 Obama himself stressed that “we have a clear and focused goal: to disrupt, dismantle, and defeat al-Qaida in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and to prevent their return to either country in the future.”53

The U.S. response will involve a military, a diplomatic, and an economic developmental component. Moreover the military role will increase, perhaps far more than has yet been officially indicated.54 Lawrence Korb, an Obama adviser, has submitted a report which calls for “using all the elements of U.S. national power — diplomatic, economic and military — in a sustained effort that could last as long as another 10 years.”55 On March 19, 2009, at the University of Pittsburgh, Korb suggested that a successful campaign might require 100,000 troops.56

This persistent search for a military solution runs directly counter to the RAND Corporation’s recommendation in 2008 for combating al-Qaeda. RAND reported that military force led to the end of terrorist groups in only 7 percent of cases where it was used. And RAND concluded:

Minimize the use of U.S. military force. In most operations against al Qa’ida, local military forces frequently have more legitimacy to operate and a better understanding of the operating environment than U.S. forces have. This means a light U.S. military footprint or none at all.57

The same considerations extend to operations against the Taliban. A recent study for the Carnegie Endowment concluded that “the presence of foreign troops is the most important element driving the resurgence of the Taliban.”58 And as Ivan Eland of the Independent Institute told the Orange County Register, “”U.S. military activity in Afghanistan has already contributed to a resurgence of Taliban and other insurgent activity in Pakistan.”59

But such elementary common sense is unlikely to persuade RAND’s employers at the Pentagon. To justify its global strategic posture of what it calls “full-spectrum dominance,” the Pentagon badly needs the “war against terror” in Afghanistan, just as a decade ago it needed the counter-productive “war against drugs” in Colombia. To quote from the Defense Department’s explanation of the JCS strategic document Joint Vision 2020, “Full-spectrum dominance means the ability of U.S. forces, operating alone or with allies, to defeat any adversary and control any situation across the range of military operations.”60 But this is a phantasy: “full-spectrum dominance” can no more control the situation in Afghanistan than Canute could control the movement of the tides. America’s experience in Iraq, a terrain far less favorable to guerrillas, should have made this clear.

Full-spectrum dominance is of course not just an end in itself, it is also lobbied for by far-flung American corporations overseas, especially oil companies like Exxon Mobil with huge investments in Kazakhstan and elsewhere in Central Asia. As Michael Klare noted in his book Resource Wars, a secondary objective of the U.S. campaign in Afghanistan was “to consolidate U.S. power in the Persian Gulf and Caspian Sea area, and to ensure continued flow of oil.”61

The global drug traffic itself will continue to benefit from the protracted conflict generated by “full-spectrum dominance” in Afghanistan, and some of the beneficiaries may have been secretly lobbying for it. And I fear that all the client intelligence assets organized about the movement of Afghan heroin through Central Asia and beyond will, without a clear change in policy, continue as before to be protected by the CIA.

There will certainly continue to be targets for America’s efforts at global dominance, as long as America continues to ravage states, in the name of rescuing them from “failing.” An emerging new target is Pakistan, where the Obama administration plans to increase the number of Predator drone attacks, despite the sharp opposition of the Pakistan government.62 It is clear that these Predator strikes are a major reason for the recent rapid growth of the Pakistan Taliban, and why formerly peaceful districts like the Swat valley have now been ceded by the Pakistan military to control by the Taliban.63

Common sense will not produce unanimous recommendations for what should happen within Afghanistan. Some observers are partial to the urban culture of Kabul, and particularly to the campaign there to improve the status and rights of women. Others are sympathetic to the elaborate tribal system that ruled the countryside for generations. Still others accept the modifications introduced by the Taliban as a needed social revolution. Finally there are the security issues presented by the increasing instability of neighboring Pakistan, a nuclear power.

What common sense says clearly is that the Afghan crisis could be eased somewhat by changes in the behavior of the United States. If America truly wishes a degree of social stability to return to that area, it would seem obvious that, as a first step:

1) President Obama should renounce JCS strategic document Joint Vision 2020, with its pretentious and nonsensical ambition of using U.S. forces to “control any situation.”

2) The United States should consider apologizing for past ravagings of the Muslim world, and specifically its role in the 1953 overthrow of Mossadeq in Iran, in the 1953 assassination of Abd al-Karim Qasim in Iraq, and in assisting Gulbuddin Hekmatyar in the 1980s to impose his murderous and drug-trafficking presence in Afghanistan. Ideally it would apologize also for its recent military violations of the Pakistani border, and renounce them.

3) President Obama should accept the recommendation of the RAND Corporation that in operations against al-Qaeda, the U.S. should employ “a light military footprint or none at all.”

4) President Obama should make it clear that the CIA in future must desist from protecting drug traffickers around the world who become targets of the DEA.

In short, President Obama should make it clear that America no longer has ambitions to establish military or covert control over a unipolar world, and that it wishes to return to its earlier posture in a multipolar world community.

It is common sense, in short, that America’s own interests would be best served by becoming a post-imperial society. Unfortunately it is not likely that common sense will prevail against the special interests of what has been called the “petroleum-military-complex,” along with others, including drug-traffickers, with a stake in America’s current military posture.

Vast bureaucratic systems, like that of the Soviet Union two decades ago, are like aircraft carriers, notoriously difficult to shift into a fresh direction. It would appear that those in America’s national security bureaucracy, like the bureaucrats of Great Britain a century ago, are still dedicated to squandering away America’s strength, in a futile effort to preserve a corrupt and increasingly unstable regiment of global power.

Just as a by-product of European colonialism a century ago was third-world communism, so these American efforts, if not terminated or radically revised, may produce as by-product an ever widening spread of jihadi salafist terrorism, suicide bombers, and guerrillas.

In 1962 common sense extricated the Kennedy administration from a potentially disastrous nuclear confrontation with Khrushchev in the Cuban missile crisis. It would be nice to think that America is capable of correcting its foreign policy by common sense again. But the absence of debate about Afghanistan and Pakistan, in the White House, in Congress, and in the country, is depressing.

Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat and English Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, is the author of Drugs Oil and War, The Road to 9/11, The War Conspiracy: JFK, 9/11, and the Deep Politics of War. His American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection and the Road to Afghanistan is in press, from Rowman & Littlefield.

His website, which contains a wealth of his writings, is here.

He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended Citation: Peter Dale Scott, “America’s Afghanistan: The National Security and a Heroin-Ravaged State,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol 20-3-09, May 17th, 2009.

Peter Dale Scott’s articles on related subjects include:

Martial Law, the Financial Bailout, and the Afghan and Iraq Wars: link

Korea (1950), the Tonkin Gulf Incident, and 9/11: Deep Events in Recent American History: link

The government can easily provide resources to help a drug addict the same way it allocates funds for its international campaign against drug trafficking.

Notes

[1] Five of the current candidates for Afghan president are U.S. ,S, citizens. The Independent (January 23, 2009) has reported that Washington is searching for a “dream ticket” to oust the incumbent and former favorite, Hamid Karzai, now condemned as corrupt. PressTV goes farther: “Washington is using its political clout to influence the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections in Afghanistan, a report says. The US embassy in Kabul has urged Afghanistan’s leading presidential hopefuls to withdraw from the race in favor of Ali Ahmad Jalali — a candidate that is more preferred by Washington, reported Pakistan’s Ummat daily. In return, US officials have promised to guarantee key positions for the three candidates — which include finance minister Ashraf Ghani, former foreign minister Abdullah Abdullah and political activist Anwar ul-Haq Ahadi — in the next Afghan government. The move received instant condemnation as flagrant US interference in Afghan politics and internal affairs. Jalali — who is viewed as the main rival of President Hamed Karzai in the August presidential elections — is a US citizen and former Afghan minister of the interior. His candidacy is seen as a direct violation of the Chapter Three, Article Sixty Two of Afghanistan’s Constitution, which states that only an Afghan citizen has the right to run for president – which means that Jalali would have to apply for Afghan citizenship first. Zalmay Khalilzad and Ashraf Ghani, two other candidates vying for presidency, also hold US citizenship” (link).

[2] Jeffrey Ira Herbst, States and Power in Africa (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2000), 71; S. E. Crowe, The Berlin West African Conference, 1884-1885 (London: Longmans , 1942), 177.

[3] Max Weber, The Theory of Social and Economic Organization (New York: Free Press, 1964), 154.

[4] Railways approach Afghanistan from the north, easy, south, and west. The only two with foothold terminals in Afghanistan itself are those built by the Soviet Union in the 1980s, from Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

[5] Diego Cordovez and Selig S. Harrison, Out of Afghanistan: the Inside Story of the Soviet Withdrawal (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 16. Harrison heard about the program in 1975 from the Shah’s Ambassador to the United Nations, “who pointed to it proudly as an example of Iranian-American cooperation.”

[6] See discussion in Peter Dale Scott, The Road to 9/11: Wealth, Empire, and the Future of America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007), 73-75, 117-22.

[7] Cordovez and Harrison, Out of Afghanistan, 163.

[8] M. Emdad-ul Haq, Drugs in South Asia: From the Opium Trade to the Present Day (New York: Palgrave, 2000), 188. According to a contemporary account, Americans and Europeans star ted becoming involved in drug smuggling out of Afghanistan from the early 1970s; see Catherine Lamour and Michel R. Lamberti, The International Connection: Opium from Growers to Pushers (New York: Pantheon, 1974), 190 –92.

[9] Alfred W. McCoy, The Politics of Heroin (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books/ Chicago Review Press, 2001), 447.

[10] McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 458; Michael Griffin, Reaping the Whirlwind: The Taliban Movement in Afghanistan (London: Pluto Press, 2001),

148 (labs); Emdad-ul Haq, Drugs in South Asia, 189 (ISI).

[11] Before 1979 little Afghan opium or heroin reached markets beyond Pakistan and Iran (McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 469-71).

[12] USA Today, January 12, 2009.

[13] Newsweek, Apr 7, 2008.

[14] Cf. S. Hasan Asad, , “Shadow economy and Pakistan’s predicament,” Economic Review [Pakistan], April, 1994.

[15] Financial Times, November 29, 2001.

[16] Times of India, November 29, 1999.

[17] Ahmed Rashid, Descent into Chaos: The United States and the Failure of Nation Building in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Central Asia (New York: Viking, 2008), 320.

[18] Rashid, Descent into Chaos, 427.

[19] James Risen, State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration (New York: Free Press, 2006), 154, 160-63.

[20] Peter Dale Scott, Drugs, Oil, and War: The United States in Afghanistan, Colombia, and Indochina (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003).

[21] Philip Smucker, Al Qaeda’s Great Escape: The Military and the Media on Terror’s Trail (Washington: Brassey’s, 2004), 9. On December 4, 2001, Asia Times reported that a convicted Pakistani drug baron and former parliamentarian, Ayub Afridi, was also released from prison to participate in the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan (link); Scott, Road to 9/11, 125..

[22] Bernd Debusmann, “Obama and the Afghan Narco-state,” Reuters, January 29th, 2009.

[23] Guardian, April 7, 2006, Independent, April 13, 2006, San Francisco Chronicle, April 17, 2006.

[24] Independent (London), April 13, 2006; James Nathan, “Ending the Taliban’s money stream; U.S. should buy Afghanistan’s opium,” Washington Times, January 8, 2009.

[25] Afghanistan News, December 23, 2005.

[26] Independent, March 9, 2009. When Obama visited Afghanistan in 2008, Gul Agha Sherzai was the first Afghan leader he met. The London Observer reported on July 21, 2002, that in order to secure his acceptance of the new Karzai government, Gul Agha Sherzai, along with other warlords, had “been ‘bought off’ with millions of dollars in deals brokered by US and British intelligence.”

[27] Mark Corcoran, Australian Broadcasting Company, 2008. “In an affidavit in his criminal case, he traced a history of cooperating with U.S. officials, including the CIA, dating to 1990. In early 2002, following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, Noorzai said he turned over to the U.S. military 15 truckloads of Taliban weapons, including “four hundred anti-aircraft missiles of Russian, American and British manufacture” (Tom Burghardt , “The Secret and (Very) Profitable World of Intelligence and Narcotrafficking,” DissidentVoice, January 2nd, 2009, link). Cf. Risen, State of War, 165-66.

[28] USA Today, October 26, 2004.

[29] Washington Post, December 27, 2008; New York Sun, January 29, 2008, http://www.nysun.com/foreign/justice-dept-eyes-us-firms-payments-to-afghan/70371/..

[30] New York Times, November 23, 1996; cf. November 20, 1993.

[31] Chris Carlson, “Is The CIA Trying to Kill Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez?” Global Research, April 19, 2007.

[32] New York Times, November 23, 1996.

[33] Wall Street Journal, November 22, 1996. The information about the drug activities of Guillen Davila and François had been published in the U.S. press years before the indictments. It is possible that, had it not been for the controversy aroused by Gary Webb’s Contra-cocaine stories in the August 1996 San Jose Mercury, these two men and their networks might have been as untouchable as other kingpins in the global CIA drug connection whom we shall discuss, such Miguel Nassar Haro in Mexico.

[34] Washington Post.

[35] Philip Giraldi, “Found in Translation: FBI whistleblower Sibel Edmonds spills her secrets,” The American Conservative, January 28, 2008. Others have written about the ties between U.S. intelligence and the Turkish narco-intelligence connection; see e.g. Daniele Ganser, NATO’s Secret Armies: Operation Gladio and Terrorism in Western Europe (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2005. 224-41; Martin A. Lee, “Turkey’s Drug-Terrorism Connection,”

ConsortiumNews, January 25th, 2008.

[36] London Sunday Times, January 6, 2008: “`If you made public all the information that the FBI have on this case, you will see very high-level people going through criminal trials,’ she said.”

[37] Huffington Post, January 6, 2008.

[38] Risen, State of War, 154.

[39] Loretta Napoleoni, Terror Incorporated: Tracing the Dollars Behind the Terror Networks (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2005), 90-97: “While the ISI trained Islamist insurgents and supplied arms, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, several Gulf states and the Taliban funded them…Each month, an estimated 4-6 metric tons of heroin are shipped from Turkey via the Balkans to Western Europe” (90, 96).

[40] Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, Cocaine Politics: The CIA, Drugs, and Armies in Central America (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998), x-xi.

[41] International Herald Tribune, January 25, 2009. Cf. Daily Telegraph (London), January 26, 2009.

[42] McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 16, 191.

[43] McCoy, Politics of Heroin, 93, 431. After the final American withdrawal in 1975, Laotian production continued to rise, thanks to the organizational efforts of Khun Sa, a drug trafficker whom Thailand was relying on as protection against the Communists in Burma and Vientiane. (McCoy, 428-31)

[44] Peter Dale Scott, ‘‘Honduras, the Contra Support Networks, and Cocaine: How the U.S. Government Has Augmented America’s Drug Crisis,’’ in Alfred W. McCoy and Alan

A. Block, eds., War on Drugs: Studies in the Failure of U. S. Narcotic Policy (Boulder: Westview, 1992), 126 –27. I presented these remarks at a University of Wisconsin conference.

[45] International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, 1999. Released by the Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C., March 2000. Production has since decreased, but is still well above 1990 levels.

[46] Richard Holbrooke, “Breaking the Narco-State.” Washington Post, January 23, 2008.

[47] I use “jihadi salafism,” an admittedly clumsy expression, in place of the more frequently encountered “Islamism” or “Islamic fundamentalism” — both of which terms confer upon jihadi salafism a sense of legitimacy and long-time history which I do not believe it deserves. The jihadi salafism I am talking about, with roots in Wahhabism and Deobandism, can be seen in part as a response to British and American influence in India and the Muslim world. Osama bin Laden points to the earlier example of Imam Taki al-Din ibn Taymiyyah in the thirteenth century, but ibn Taymiyyah’s jihadism was in reaction to the Mongol ravaging of Baghdad in 1258. As I have demonstrated elsewhere, history abundantly shows that “outside interventions are likely if not certain, in any culture, to produce reactions that are violent, xenophobic, and desirous of returning to a mythically pure past” (Scott, Road to 9/11, 260-61).

[48] Richard Holbrooke, “Breaking the Narco-State.” Washington Post, January 23, 2008.

[49] Holbrooke, “Breaking the Narco-State.”

[50] David Corn, “Holbrooke Calls for “Complete Rethink” of Drugs in Afghanistan,” Mother Jones Mojo.

[51] “`By forced eradication we are often pushing farmers into the Taleban hands,’ Mr Holbrooke said. `We are going to try to reprogramme that money. About $160 million is for alternate livelihoods and we would like to increase that’” (London Times, March 23, 2009, link).

[52] Guardian, March 24, 2009.

[53] NewsHour, PBS, March 27, 2009. Cf. Christian Science Monitor, March 27, 2009.

[54] “Obama’s [May] 2009 [supplementary] war budget sheds light on the expansion of the war in Afghanistan and Pakistan. …The Department of Defense states that funding for the Afghanistan War will increase to $46.9 billion in 2009, a 31 percent rise over the $35.9 billion in 2008 and the $32.6 billion in 2007…. This $11.3 billion increase includes an additional $2.8 billion for the Afghanistan Security Forces Fund, $400 million for the Pakistan Counterinsurgency Capability Fund and $4.4 billion for MRAPs designed for use in Afghanistan. Increased troop levels will also account for a portion of the increase” (Jeff Leys, “Analyzing Obama’s War Budget Numbers,” Truthout, May 4, 2009, link).

[55] “Further Military Commitment in Afghanistan May Be Toughest Sell Yet,” Fox News, March 25, 2009. In a little-noted speech on October 17, 2008, Holbrooke also predicted that the war in Afghanistan would become “the longest in American history,” surpassing even Vietnam (NYU School of Law News, link).

[56] TheEndRun, April 6, 2009.

[57] RAND Corporation, “How Terrorist Groups End: Implications for Countering al Qa’ida,” Research Brief, RB-9351-RC (2008).

[58] Gilles Dorronsoro, “Focus and Exit: an Alternative Strategy for the Afghan War,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 2009.

[59] Orange County Register, March 30, 2009.

[60] “Joint Vision 2020 Emphasizes Full-spectrum Dominance,” DefenseLink, emphasis added.

[61] Michael T. Klare. Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict (Henry Holt, New York 2001; quoted in David Michael Smith, “The U.S. War in Afghanistan,” The Canadian, April 19, 2006. Cf. Scott, Road to 9/11, 169-70.

[62] Christian Science Monitor, April 8, 2009.

[63] Cf. “Holbrooke of South Asia,” Wall Street Journal, April 11, 2009.