Paul Rogers

The demolition of a French empire at Dien Bien Phu is inspiration to a Taliban aiming to erode the resolve of the United States and its allies, writes Paul Rogers.

There have been many suggestions among media and military analysts since 2003 of possible parallels between the war in Iraq and the United States imbroglio in Vietnam that ended so humiliatingly in 1975. The argument is most prominently made by critics of both wars, though it has also been articulated by defence analysts and officials concerned that the US learns the “right” lessons from its costly Vietnam experience.

Three aspects of this approach are notable, however. First, fewer such comparisons have been made with the conflict in Afghanistan, which arguably in some respects offers a closer “fit” with the Vietnam War than does Iraq. Second, the Vietnam precedent is invoked as if the devastating wars in that country started only with the significant American involvement in the mid-1950s and later, and almost completely ignores the earlier, post-1945 clash of arms between Vietnamese nationalists and French colonialists. Third, when parallels (whether Iraqi or Afghan) are drawn, they tend to be presented exclusively from the viewpoint of the Americans. It is as if “only” the United States (and by extension western forces or combatants in general) have the capacity or the interest to draw lessons from the past.

This context makes all the more interesting a report which cites the view of an (anonymous) Taliban media source that much of the military activity in Afghanistan in the coming months will resemble the tactics employed by the Vietminh guerrillas and their renowned military commander, General Vo Nguyen Giap, in the war against French control of “Indochina” (see Syed Saleem Shahzad, “The Taliban talk the talk“, Asia Times, 11 April 2008).

The reference is startling and ominous. In the early 1950s, the Vietminh – faced with an imbalance between their own forces and conventional French military power – concentrated on attacking isolated garrisons in the northern part of Vietnam well away from the main colonial centres of control: Hanoi, Haiphong and the densely populated Hong (Red) river delta. This strategy, combined with attacks on French supply-lines, gradually wore down the French military and political leadership’s resolve.

Now, it seems, the Taliban aim to do the same against an equivalently “asymmetrical” enemy: Nato, and the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) forces in Afghanistan.

The Taliban shifts gear

The Taliban source highlights the success of this kind of strategy against Pakistani army units in the border districts; recent assaults on the key supply-routes delivering equipment and provisions through Pakistan to Afghanistan also fit the pattern. The latter have included the destruction on 24 March of forty petrol-tankers at a border-post, and the detonation on 1 April of a bridge on the Indus highway in Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province.

Nato’s concern with its dependence on the insecure Pakistan-Afghanistan roads is reflected in its agreement with Russia (at the Nato summit in Bucharest on 2-4 April) on the land-transit of “non-lethal supplies” to its troops in Afghanistan. At the same time, other parts of Nato exhibit a blithe confidence in the coalition’s capacity to counter such Taliban initiatives; for example the ISAF spokesman Brigadier-General Carlos Branco dismisses Taliban claims of a new strategy and expresses confidence in Nato’s superior firepower and ability to counter the movement’s initiatives.

Carlos Branco responds to the Vietnam analogy by comparing Giap’s use of coordinated guerrilla and conventional attacks backed by a range of weaponry, with the far less effective Taliban campaign. The group, he argues, have little to show for the last few years; Nato’s firepower remains clearly superior and Taliban claims of a new approach are boasts without substance.

The director of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), reporting on a seven-day visit to Afghanistan, reaches a somewhat different conclusion. Jakob Kellenberger stated on behalf of his organisation: “We are extremely concerned about the worsening humanitarian situation in Afghanistan. There is growing insecurity and a clear intensification of the armed conflict, which is no longer limited to the south but has spread to the east and west.” He continues: “The harsh reality is that in large parts of Afghanistan, little development is taking place. Instead, the conflict is forcing more and more people from their homes. Their growing humanitarian needs and those of other vulnerable people must be met as a matter of urgency.”

The ICRC – which has extensive experience in humanitarian work in Afghanistan, including after many other NGOs left in response to deteriorating security there – thus presents a bleaker prognosis than Nato officialdom (see Laura King, “US troops gird for a spring offensive in Afghanistan“, Boston Globe, 16 April 2008). But in any case, does what is happening in the country relate at all to the Indochina war of 1945-54 and the tactics of Vo Nguyen Giap and the Vietminh?

The Dien Bien Phu drama

The Vietminh originated as a unified force in the face of Japanese occupation in the early 1940s, under the political leadership of the nationalist-communist leader Ho Chi Minh. After the Japanese collapse and the end of the war in August 1945, the Vietminh came to control substantial parts of northern Vietnam; the return of the French in 1946 to reclaim their colonial lands, however, forced the Vietminh to retreat to rural areas and attempt to wage war from bases there (see David Marr, Vietnam 1945: The Quest for Power [University of California Press, 1997]).

In the 1946-50 period the anti-colonial struggle was small-scale as the Vietminh slowly built its support. The Vietminh gained an important external source of arms after the Chinese Communist Party won the civil war and took control of China (Vietnam’s northern neighbour, as well as its ancient and intimate rival) on 1 October 1949. In the next four years, the Vietminh conducted a series of bitterly-fought guerrilla actions which resulted in their securing control of most of the rural areas in the north of Vietnam. But the French retained military superiority and administrative control in the major cities and the densely populated Hong delta. By 1953, the war was stalemated, though heavy French casualties were increasing hostility to the war in France itself.

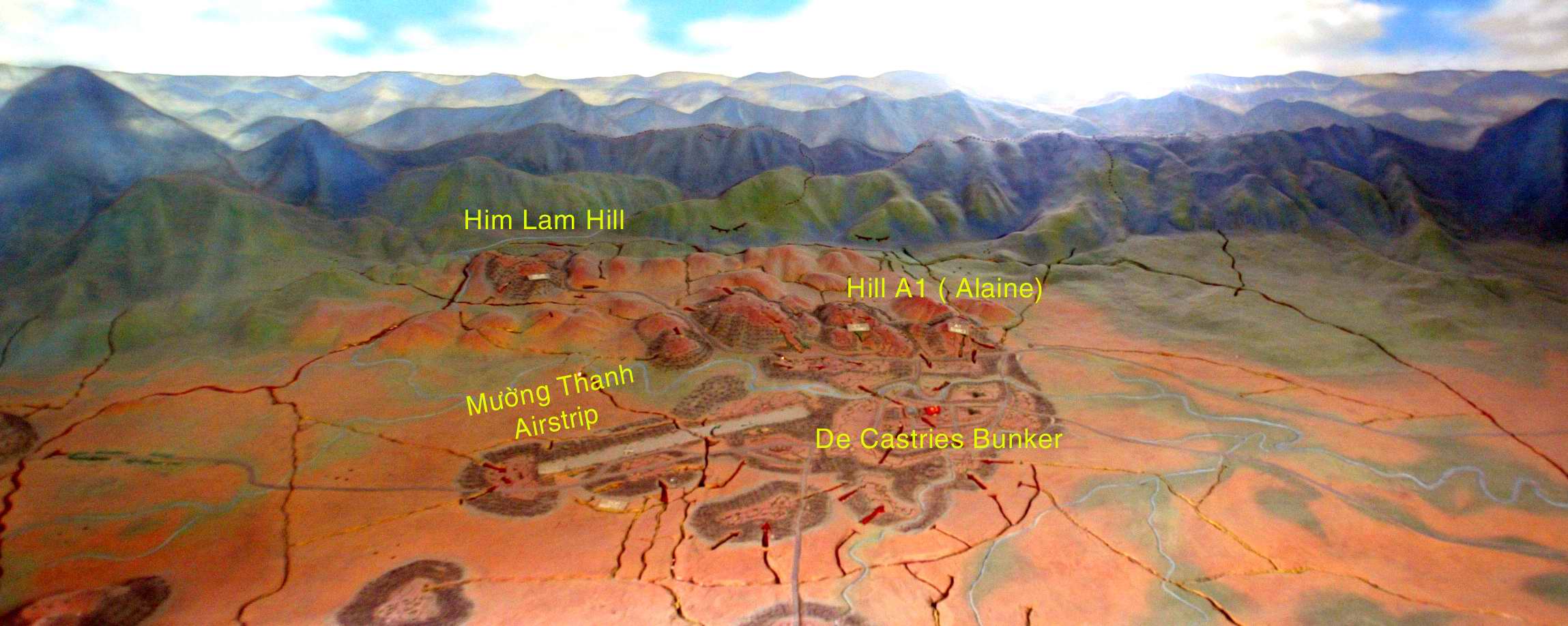

Most of the fighting had been taking place during the dry winter seasons, but in 1953-54 Giap attempted to open up a new front by aiding the Pathet Lao insurgents in neighbouring Laos. This was potentially disastrous for the overstretched French, who responded by occupying and reinforcing the remote town of Dien Bien Phu. The garrison town was strategically placed to intercept Vietminh supply routes to the Pathet Lao, but also hundreds of kilometres from other French positions.

It was a move too far. The French did not have the resources to supply Dien Bien Phu by air; the Vietminh controlled the access routes, and mounted an epic effort to transfer supplies (a huge amount of them by bicycle) across densely forested and mountainous tracks to encircle and besiege the French forces.

After a bitter siege in which many thousands were killed on both sides, the French garrison surrendered in early May 1954. The French may still have controlled Hanoi, Haiphong, Saigon and most of Indochina, but the devastating defeat at Dien Bien Phu finally crushed public support in France for the war; within three months, a ceasefire and withdrawal were agreed (see Martin Windrow, The Last Valley: Dien Bien Phu and the French defeat in Vietnam [Orion, 2005]).

East Asia, West Asia

Three obvious comparisons can be drawn between Indochina and Afghanistan. First, the seasonal nature of both conflicts (in Indochina the fighting was intense during the winter dry season and far less during the summer monsoons; in Afghanistan, the snows limit warfare in winter, so most fighting is done in spring and summer). Second, the Vietminh had opposed the Japanese and the French, so were experienced in fighting foreign enemies long before the Americans emerged to try to subdue them; in the same way, the Taliban can be regarded as inheriting the mantle of the fighters who defeated the forces of the mighty British empire in the 19th century, as well as successors of the anti-Soviet mujahideen of the 1980s. Third, the Vietminh had help from the Chinese communists across the border, just as the Taliban have ample support in western Pakistan.

There are also significant differences. The Taliban do not have a political leader of the power of Ho Chi Minh, nor a military commander with the quite extraordinary capabilities of General Vo Nguyen Giap.

The asymmetry of their forces with Nato’s may be even greater than with the respective sides in Vietnam (even if the alliance pleads shortages of helicopters and other equipment). Yet the recent experience of the anti-Soviet struggle, the emergence of a new generation of military commanders, and – perhaps above all – the mobilisation of centuries-old memories of opposition to foreign occupations, are potent weapons in the Taliban armoury.

The heart grown tired

In balancing always inexact historical analogies against always singular current circumstances, caution is in order. Yet there is another relevant factor that may indicate the direction of the deeper current of events in Afghanistan: whether Nato can maintain the will to continue to fight and build in Afghanistan for the many years that may be necessary. Three current news items are relevant in this respect.

The first reports a claim that British forces in southern Afghanstan have killed as many as 7,000 Taliban – and no less than 6,000 of them since January 2007 (see Michael Smith, “Army Has Killed 7000 Taliban”, Sunday Times, 13 April 2008). The human costs of this carnage are grave enough, but leaving that aside it might be assumed that the figure is regarded as a sign of military success. Not so: the story reflects an intelligent recognition that deaths on this scale “are a boost for the Taliban when fighters recruited from the local population are killed, as the dead insurgent’s family then feels a debt of honour to take up arms against British soldiers.” The assessment, put bluntly, is that killing Taliban makes even more enemies.

The second news item indicates a recognition in the Pentagon that troop numbers in Afghanistan are inadequate for the task assigned to them, as Taliban militias seek to avoid open conflict with well-armed Nato forces and move to operate in areas where Nato is largely absent (see Jonathan S Landay, “U.S. Seeking Troops To Send to Afghanistan“, Miami Herald, 16 April 2008). The Pentagon is seeking 7,000 more troops to supplement the 3,200 United States marines that have been deployed in early 2008 (and are due to return by the year’s end, with no replacements yet identified. Even in these circumstances, most Nato allies will not agree to increase their forces.

The small prospect of troop withdrawals from Iraq was still alive until the upsurge in violence there – reflected in the mood of the senatorial hearings of David H Petraeus and Ryan C Crocker, and the statement of George W Bush on 10 April 2008 – effectively killed it (see “A war of decades“, 10 April 2008). Thus the combination of military overstretch and a lack of Nato solidarity means that the United States is facing conflicts in two areas without the forces it believes it needs.

The third report concerns the level of US casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan (reflected in new figures released by the Pentagon that barely registered in the media). The US military death-toll in the two main wars is now 4,492; but at least as significant is the huge number of wounded, together with the troops evacuated back to the United States because of accidental injury or mental of physical illness (see Pia Malbran, “Military Releases High Casualty Figures“, CBS News, 14 April 2008). The number of those injured in combat now runs to 31,590, and another 38,631 have been returned to the United States for non-combat problems. Some of the latter may have been withdrawn for routine treatment or tests; but the great majority are, at the very least, indirect casualties of war.

Furthermore, a increasing proportion of recent veterans has been reporting to the department of veterans’ affairs (DVA) for treatment, frequently for problems originating during active service. The DVA had treated 299,585 from January 2002 to January 2008, 120,049 (40% of the total) for mental-health disorders.

These three stories together portray a very different picture of the strategic predicament of the United States and its allies in Afghanistan (and Iraq) from the optimistic comments of Brigadier-General Carlos Branco – and perhaps a more accurate one. In 1954, the French gave up in the face not just of “external” pressure and setback but of an “inner” corrosion of their resolve.

Nato in general and the United States in particular may not yet be at that point: but they face wars that could stretch for decades, and – whether or not they suffer an Afghan or Iraqi equivalent of Dien Bien Phu – their opponents are expecting their hearts eventually to fail.

Paul Rogers is Professor of Peace Studies at Bradford University and is International Security Editor for Open Democracy where his weekly column has appeared since September 26, 2001. His most recent book is Why We’re Losing the War on Terror (Polity, 2007) – an analysis of the strategic misjudgments of the post-9/11.

This article was published at Open Democracy on 17 April 2008. It was posted at Japan Focus on April 25, 2008.