Why I Went to

Imai Noriaki

Introduced by Norma Field

Translated by Scott Mehl, Ayumu Tahara, Ariya, and Norma Field

The December 2003 deployment of Self-Defense Force troops to Iraq by the Koizumi administration took Japan closer to the practical repudiation of the non-belligerancy principle of Article 9 than any prior move in its more than half-century of existence. Of course, as the very existence of “self-defense forces” attests, Article 9 had already been subjected to considerable abuse by interpretation, virtually since inception. Nevertheless, the deployment to Samawah was controversial. It stirred visible opposition in the beginning even though it soon faded, at least from public view. Thus is a status quo created.

When three young Japanese were captured and held hostage for eight days in April of 2004, however, with withdrawal of the troops made the condition for their release, controversy erupted with a vengeance. Once they were released, however, relief was quickly overwhelmed by hostility. Encouraged by the mass media, members of the general public and politicians vented their wrath on the young people and by extension, their demanding families who had caused so much “trouble” through their “selfish” actions. Quite apart from sanctimonious pronunciations about “personal responsibility,” the government, by disclosing the public sums spent on the hostages, including stiff reimbursement fees for official return transport that it insisted upon, effectively reinforced the image of the three as thoughtless trouble-makers. And last but hardly least, the Internet, especially the anonymous 2-Channel discussion board, played a memorable role in fanning the flames of furor. Ironically, it was a statement from then Secretary of State Colin Powell about the importance of risk-taking that had a quelling effect.

The extraordinary display of national hostility that was the “hostage incident” (hitojichi jiken), as it has been called, condenses a number of factors worth teasing out. Social relations and the invocation of a national community on the Internet are an obvious one. Although the issue of troop deployment itself was eclipsed, the response to the hostage incident suggests the kinds of issues ranging from the strategic to the psychological that are little articulated in the struggle over Article 9. Neither a culturalist analysis (Japanese are hierarchical, anyone who violates authority is punished), as offered by Onishi Norimitsu in the New York Times, nor a circumscribed political one (it was Koizumi who had staked his career on troop dispatch, and responsibility for any harm befalling Japanese citizens as a consequence had to be shifted elsewhere) as effectively laid out by Philip Brasor in the Japan Times [1], can be more than a beginning to understand the phenomenon. We need to take into account long-term frustrations with the economy as well as the demonstrable lack of “personal responsibility” on the part of government officials through the years of the thinning social safety net (the pension scandal—of nonpayment by high officials—would break later in the same month as the hostage incident) in order to grapple with the character and intensity of the backlash greeting the three, as well as the lack of sympathy for the young man (Koda Shosei) who was captured and beheaded in November of 2004. We would also need to consider how the amorphous yet pervasive sense of a society that had lost its purpose after the postwar recovery, miracle, and bubble and recession found expression in this moment.

The most thorough structural analysis, one taking into account both general conditions and those specific to Japan, would, however, be wanting if it failed to reflect on the nature of the rupture that the incident precipitated. In a war zone more and more considered too dangerous by international news agencies and establishment reporters, it was left to freelance journalists literally taking their lives into their hands to produce reports independent of official sources. Of the three Japanese hostages, Koriyama Soichiro (then 32), was a freelance photojournalist; Takato Nahoko (34) had experience working with Baghdad streetchildren; and Imai Noriaki (18), who had called himself a freelance journalist from his high school days, wanted to investigate depleted uranium (DU) munitions. Each was driven by a need to see for him or herself what was actually going on and acted to realize that desire. Our bureaucratized world counts on the inertia yielded by everyday busyness to enforce its conventions. Routine discourages the very experience of the desire to “see for oneself” outside the institutions of consumption, notably tourism. To witness young people who had actually followed through on that desire must have been breathtaking to some and infuriating to others. There is something deeply unsettling about recognizing that it is not necessary to go along with the pretense that the world is as described, and to see actual individuals, not so different from those around us, making that breach at great personal risk. The anonymity of the Internet attacks offers a telling contrast.

In the three years since the incident, the three have gone on with their own lives. Imai, who was only 18 at the time, is understandably most visibly in the throes of self-definition. [2] As a college student, he has worked hard to involve himself in the community, starting up a portal internet site with fellow students. Through his interviews and volunteering, he has taken up such issues as local veterans’ war memories, intersex, and the global water crisis. Recently, as if coming full circle, he has been forming ties with the Muslim student community, learning about their religious practices and everyday life in a provincial Japanese city. If there is any basis for characterizing Imai’s decision to enter Iraq in spring of 2003 as naive, among other qualities, then his writings and subsequent conduct suggest that it should be understood as a willful, indeed, purposeful naivete.

Part 1 below excerpts from his book, Why I Went to

Parf 2, the only selection not principally concerned with Imai, calls for separate comment. It is an English translation of a letter written at the time of the hostage crisis by the friend of a member of the Violence Against Women in War

If the Internet rage directed at the hostages is one representation of this moment in postwar Japanese history, this letter is quite another. It reflects the fruition of some of the most promising developments in postwar Japan: (1) the commitment to peace dating back to the earliest period after the end of the war; (2) the disposable income from the decades of “peace and prosperity” that meant young people traveled widely, and beyond Europe and the U.S.; and (3), most immediately, the grass-roots ties developed through the diffuse effects of (1) and (2). When people talk about generations, they are talking about history. Ms. Hosoi notes that the overwhelming number of Japanese who have involved themselves in Iraq are in the latter half of their thirties, the generation that took the value of international friendship for granted. (This makes Imai Noriaki something of an exception.) She speculates that the conservative reorganization of education has had the effect of making younger people more inward-looking and at the same time, contemptuous of other Asian countries. One of the common criticisms directed at the hostages was “Why don’t you stick to

We must not, finally, in our concern to analyze the crushing hostility directed at the hostages, neglect to acknowledge the outpouring of support during their captivity and upon their return, so obscured by media fascination with the attacks. Seeing an image of Imai’s face, the lawyer Nakajima Michiko said to herself, “That’s me, fifty years ago,” and rushed to join others to sit in at the Prime Minister’s residence [4]. Indeed, we might understand the cumulative aspirations for a new Japan and a new world on the part of postwar generations expressed in support for the hostages as responding to the will-to-hope inchoately expressed in the radical naivete of their act.

[1] Onishi’s article may be read here,

Brasor’s here (both accessed 19 December 2007).

[2] The three have written their reflections on their hostage experience in the stunning photojournal Days Japan (Vol. 4, No. 9, September 2007). Takato Nahoko grew up in

[3] Boku ga iraku e itta wake (

[4] For Nakajima’s own antiwar activism, see a Japan Focus article “Gendered Labor Justice and the Law of Peace,” Another important individual, among many, who dedicated himself to mobilizing support was Minowa Noboru (1924-2006), eight-term LDP lower house representative from Hokkaido who served, among other capacities, as parliamentary vice minister of the (then) Defense Agency and postal minister. He declared Prime Minister Koizumi’s dispatch of the SDF to

PART 1 Why I Went to

From Chapter 2

The attested dangers of depleted uranium (DU) shells

Even in

As for the specific dangers of DU, there are reports by doctors in

“According to many doctors at the Samawa Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinic, the cancer rate among children started increasing rapidly from 1991, and leukemia and brain tumors have become three to four times as frequent. On top of that, the rates of miscarriage and abnormal deliveries have doubled or tripled” (DU Report 2).

Carol Picou, who enlisted as a U.S. Army nurse during the Gulf War, describes the symptoms of radiation sickness as follows:

*Our babies [i.e., babies of returned Gulf War soldiers] are born without thyroids. Veterans exposed to radiation have been getting thyroid cancer. *We’ll have to take synthroid [a thyroid hormone] for the rest of our lives. *Doctors are suspicious that there are squamous cancer cells growing in my uterus. They’ve made me undergo twelve tests already and I’ve been ordered to repeat those tests. My muscles have atrophied.

There are times when I can no longer control my bladder or my bowels. *The army issued me diapers and said I could catheterize myself for the rest of my life. In fact, I’ve been catheterizing myself since 1992 and wearing diapers for just as long.

Our babies are born with congenital birth defects. Since coming back to the

While I was looking into the problem of DU shells and nuclear contamination, I was learning too about the dangers of exposure to other forms of radiation, and what I found was mind-boggling. In December 1949

What got me started, then, was the DU shells, but I was beginning to have questions about atomic power and nuclear energy as well. From then on, I wanted to tackle the issue of atomic energy.

Why was so little attention given in

Deciding to go to

On the 31st of January, 2004, the “NO!! Small-scale Nuclear Weapon (DU) Sapporo Project” hosted a talk, which I attended, by Ms. Sato Maki of the JVC (Japan International Volunteer Center), titled “Iraqi Children Now: The Effects of DU Shells.”

On February 13th the inaugural meeting of the Campaign for Abolition of Depleted Uranium was held in

At a meeting the day before, we discussed the possibility of putting together a picture book about DU shells, and the

“So who’s going to go?”

“Why don’t you go, Imai?”

“If Imai goes and writes about what he sees, then it’ll be more likely to appeal to young people.”

And I was in fact quite interested in the culture and the way of life of the Iraqi people and wanted to go. But I also had serious doubts. For starters, when I told my family that I wanted to go to

This time, whenever we talked about how things were dangerous in

This time Ms. Takato would be going with me. She and my mother started talking to each other and began researching. Ms. Takato tested me, asking me pointblank:

“You won’t be free to go wherever you want in

“I know I could die from gunfire or be killed by suicide bombers. I’ve thought about these things and made up my mind. I’ll listen to you. I’ll be cautious about whatever I do.”

And so I got Ms. Takato to agree first. After that, my mother and grandmother gave me the OK. My 84-year-old grandmother said, “Noriaki, you want to be a journalist, and you’ll be with Ms. Takato, so go, and get the experience.” I was moved by these words, thinking how strong she was, my grandmother who was born in the Taisho era.

My big brother Yosuke—the guardian of the family—said, “You have no reason to be going to

On March 13th Ms. Takato gave a talk called “Iraq Through a Volunteer’s Eyes: A Message from the Children of Iraq.” There again I spoke with her and reaffirmed my desire to go to

I was even prepared to die

In the end my decision to go to

Of course, the decision was mine alone. Not only was there the risk of dying in a suicide bombing or being caught in a crossfire, but there was also the chance that I would be exposed to radiation from DU shells, as I knew from talking with people who had experience covering Iraq. To tell the truth, I was worried about whether things would be okay if I had children five or ten years down the road. But the only thing for it was to make the effort. I would take the risk and go.

I planned to investigate the adverse effects of depleted uranium bombs and go on a JVC [

I understood this well enough myself, and argued about it with my parents before making my decision. What I couldn’t foresee was the possibility of being taken hostage …

Once I’d made up my mind to go I took a part-time job to supplement the thousand dollars I’d been saving annually. I also got some money from fundraising, and I borrowed some from my parents. A round-trip flight to

I spent three days in

Chapter 3

Eight Days of Being Held “Hostage” (And I Have No Bitterness)

April fourth, a twelve o’clock flight from

“So what happens to me if I lose my passport? Probably get deported immediately. That would be just great.”

When I go down to the hotel lobby, they immediately tell me to go back to my room. I’ve gotta say,

In a waiting room in the

My plane touches down in

It’s safe if we bypass Fallujah

Meet up with Ms. Takato at the hotel. At first our plan was to leave that night. But there’s the chance that Fallujah will be blockaded, and when the taxi driver tells us it’s risky, we decide to wait till the following night.

On the day of the sixth, then, Ms. Takato focuses on gathering information. She checks Yahoo News at an internet café; she listens to what the drivers are saying at the cab stand; she gets the news from the capital,

Book jacket,

What’s this thing called “the future”?

There’s a regular bus from

Now, just in terms of safety, I think the bus would be the best way to go. We’d be riding with the locals. Besides, bus fare is about the same as cab fare for three.

Mr. Koriyama said, “I’m going alone if I have to. War zones are always dangerous. If you start worrying about safety, you’ll never go.”

There were some kids who had hepatitis that Ms. Takato wanted to take to the hospital. I felt like I wanted to go, too, but I decided to leave the final decision up to them. Ms. Takato hesitated, but in the end she said, “Let’s go to

An easy border crossing

When we’re packed and ready we go to the internet café again to check the latest news, then leave. The clock reads 10:30 p.m. Cab fare for one to

We’re nervous, of course, but we’re reassured when the driver says we’ll be okay if we bypass Fallujah. It’s like we’ve been given our authorization papers or something. The driver has some citrus fruit and sweets for us, but we don’t stop to eat, and we make do with just water. The driver doesn’t speak English so Ms. Takato speaks in Arabic with him.

We know at this point sporadic fighting has broken out in Fallujah, but we couldn’t know that a real battle is taking place. Our plan is to go back if the border is blocked. We learned later that right after we left, the situation in Fallujah deteriorated rapidly.

There aren’t many cars on the road and there are stretches when we don’t see any cars at all. Inside

Strangely, though, our taxi drives on by all the cars parked on the side of the road and eases right up to the gate. I wonder if the other drivers are napping. It’s past two in the morning. The electricity is off in the border inspection office. We hand over our passports, pay ten Jordanian dinar (about fifteen hundred yen), and get through the Jordanian side of the border with no problem at all. It’s almost disappointing.

From there it’s a two- or three-minute drive to the Iraqi side of the border, and the American army is nowhere to be seen. Our passports are checked again and we take a few minutes to fill out a simple entry questionnaire. We’ve heard a rumor that there might be AIDS testing at the border, which makes us worry about possible infection from reused needles, but no AIDS testing is being done.

To lower the chances of being robbed we rest for a few hours at the

Filling up at a roadside gas station. There’s a restaurant there, and people are gathering. We pull over and park, and Ms. Takato and Mr. Koriyama get out and talk with some children and take pictures of them. I stay in the vehicle and keep watch over our bags. I was able to take a bunch of pictures at the entrance to the restaurant, too, but the film was confiscated during our captivity.

Once we’re in

“Where are those three from?”

American army vehicles and hundreds of troops come into view as we approach Fallujah. Our taxi exits off the highway and we fill up for the third time. It’s a little before eleven in the morning. There are two lines of waiting cars; the lines must be thirty or forty meters long. There are no houses in the area.

Our taxi gets in line and right away a boy comes up and asks the driver:

“Where are those three from?”

I was surprised—I hadn’t known he was there, right by the car. The driver answers, “They’re Japanese.”

Then the boy goes running headlong back up the road leading back to the highway. There’s a white car parked there, and the boy tells whoever’s inside what he’s found out. Our driver wonders aloud why the boy would ask such a question, but I don’t give the matter a second thought. Ms. Takato had left the taxi and was playing with some of the kids from the cars nearby, and now she comes back. I wave to the children and think how cute they are.

Japanese, bad

That’s when it happened. Ms. Takato gasps. When I turn around there’s a group of people standing right in front of us with rocket shells and Kalashnikov rifles. Their faces are all covered.

Their car has pulled up alongside our cab, and they make us move the taxi to the side of the road. Our cab is then surrounded by a group of about a dozen armed militiamen, who are joined by another larger group of probably several dozen who have gotten out of some of the cars waiting to gas up. They are talking loudly, but I don’t understand what they’re saying.

“Yaabaanii, muu zain! (Japanese, bad!)” one of them shouts, drawing a finger across his throat. I remember his face clearly. He was shouting as if he’d lost it. The others don’t stop him. They only look on.

Ms. Takato shouts “La! La! La! (No!),” but it’s no good.

I don’t remember anything clearly except the man who shouted “Yaabaanii, muu zain!” I was stunned.

The driver is doing everything he can to persuade them to stop. Ms. Takato is saying “Shuwaiya! (Wait!)” over and over, gesturing frantically, but they pay no attention. They tear open our bags and take our passports. Same with our cameras and wallets. Then they take the bags too. Not one of them speaks English. I’ve never witnessed anything like this before, so it goes without saying that I am utterly terrified, but I can’t look away. I lose sight of my surroundings, Ms. Takato and Mr. Koriyama included.

With a gun to his face, Mr. Koriyama gets taken to the first group’s car. Ms. Takato and I are threatened with grenades and made to get into another car. Aside from the driver, there are two masked men sitting in the passenger seat. One of the men in the passenger seat holds up a grenade for us to see. Under the seat there’s a machine gun. The men’s bodies are wrapped in machine gun shells and grenades, just like Rambo. I have no idea how much time passed as we were sitting there, terrified, not knowing what would happen to us.

Ms. Takato is crying, and I just sit there holding her hand. I do my best not to cry, but I’m shaking uncontrollably and I start sniffling. It really was terrifying. I’d rather not remember it.

And then I start to wonder if we’ve been captured by suicide bombers. Their clothes make me think of the Palestinian suicide bombers I’ve seen on TV and in the newspapers.

“Are you a spy?” “Why was the Japanese army sent here?”

Soon after, they brought Mr. Koriyama, blindfolded us, and took us somewhere. We came to a place like a warehouse, though I don’t know exactly where it was. And then the interrogation began. It lasted twenty-five or thirty minutes. The man who introduced himself as the General was asking the questions in English. It wasn’t really good English, and Ms. Takato gave almost all the answers.

I’ve forgotten practically everything they asked us. The only questions that have stayed with me:

“Are you spy?”

The other people there were asking, “Japanese army leish hon? (Why is the Japanese army here?)”

The General was also saying, “Why do you send Japanese Army?”

Ms. Takato answered, “We’re here as humanitarian aid workers,” but the General didn’t seem to understand her. Then, in desperation, she explained her own actions, telling them of her affection for

“I came to Fallujah to bring pharmaceutical supplies to the hospitals. There’re some great kebab places in Fallujah, aren’t there.”

I think this went on for about fifteen minutes. Little by little the conversation changed, and the General said: “We need to do a background check on you, so if you could write your home addresses and your email addresses. Your lives are secure. Sorry, sorry.”

“If you check with our hotel in *

But while we were eating a fight broke about between the group we were with and another group from outside. They all had furious expressions on their faces. I’d guess the other group was telling our group to kill us. All I know is that they looked furious and were yelling ferociously.

I think we were fortunate. The General was taking an interest in our activism, and while we were speaking with him we had the feeling he understood us well. Had we not been able during that first interrogation to clear ourselves of the suspicion that we were spies, without a doubt we would have been killed. I think the Iraqis who were dealing with us were people with principle.

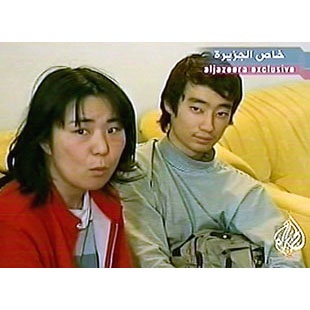

A frightful video shoot

After we eat, a fat man comes in with a video camera. He says something in Arabic and starts recording. We would later find out that the images were aired all over the world via Qatari TV, the Qatar-based satellite television station of Al-Jazeera.

All three of us were blindfolded, then they singled me out. They took the blindfold off and held a knife to my throat. The point of that knife was in all truth right up against my neck. After brandishing the knife like that they held the barrel of a machine gun to my head. I was the only one they did these things to. It’s terrifying to feel you can be killed any minute. There are no words to express it.

Now some men in masks start shouting, “No Koizumi! No Koizumi!”

The whole thing lasted maybe a few minutes, but for us it felt incredibly long. As soon as they stopped recording I reflexively brought a hand up to my neck. It looked like Mr.

The video shoot began so suddenly that we became even more nervous than we already were. They seemed to have asked us in Arabic to cry, but I didn’t understand it. Nor did I know that they were showing our passports; basically, I didn’t know what was going on. But since our voices had left us from fear, they didn’t think we’d seemed scared enough, so they started taping a second time.

It was said later that we’d staged this whole thing. That’s an unbearable accusation. We were helpless. I never want to see that video. Not even now. I don’t want to remember it.

When the taping was finished, the militiamen said, “Sorry, sorry.”

Mr. Koriyama told us afterward that the video camera looked new, probably a Sony. The men seemed pretty used to handling a camera. We couldn’t understand this, and even now, it seems strange to me that they knew how to run a camera.

Interrogation and dialogue

Once they finished taping the second time they blindfolded us again and took us somewhere else. The first two days they treated us roughly. When they put us in the car they shoved us inside, and once we were in they hit us when we didn’t keep our heads down. The place they took us to was like a big meeting room. It might have been a part of someone’s private residence. Along the walls there were big wooden couches and on the floor, rugs.

There, another interrogation began. Even the following day various group members would come one after another asking us, “You’re spies, aren’t you?” In the first two days we must have been interrogated four or five times. They all asked the same questions; they must have believed in all seriousness that we were spies. We thought the General had understood our situation. Anxiety reared its head again.

The General showed up in the room a little while later and started talking to Ms. Takato about faith.

“What do the Japanese believe in? What religion are you?”

“I’m a Buddhist. In

“What are you saying? There is only one god, and that is Allah.”

But little by little they come to understand what Ms. Takato is saying. “It’s all right for there to be many ways of understanding God,” is the conclusion they seem to have come to. During those tense hours I learned from the depths of my being the importance of mutual understanding through dialogue. In the end the General said, “We’ll release you tomorrow or the next day,” and left the room.

(Of course, at this time we had no way of knowing that there was a threat to “burn us alive,” or that they were offering to release the three of us in exchange for the complete withdrawal of the Self-Defense Forces within three days’ time.)

Even as these dialogues were taking place we kept hearing the sounds of trench mortars exploding. They were powerful enough to make the house shake.

Transported again at nightfall. When they removed the blindfolds we saw militiamen equipped with Kalashnikov rifles. To my surprise, many of these men were dozing. We rolled up in some blankets and slept, too. I believe it was around eleven o’clock.

Hopes betrayed

The second morning about ten people came to greet us one by one.

“Al-salaamu ’alaikum” (“Good day”).

They seemed to be on friendly speaking terms with the militia, too. I had the impression that these armed men had the backing of the people.

The soldier standing guard over us gestured and conveyed to us that he was going to Fallujah soon. I wonder whatever became of him. The toilet was outside so the guard had to come, too, but he very kindly led me by the hand.

We were moved twice that day. They blindfolded us and drove us somewhere again, and by evening we had arrived at our second room. It was dark and cramped and musty and through the window there was just enough moonlight for us to be able to see. The room was only some fifteen feet square and filled with things, so it felt even more cramped. Usually our guard was in the room with us, but he went outside to sleep. From outside came the sound of gunshots, ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta.

The three of us could talk to each other, but rather than speak in Japanese among ourselves, we tried to converse in gestures with the militiaman. One soldier said to us, “My parents and children have been killed.”

Once when he came back from the toilet Mr. Koriyama said, “You can see the fighting outside. There’re flashes.”

Our blindfolds had been taken off so we could see the light from the bombings when we went to the toilet. In order to see the fighting, I said, “I need to go to the toilet, too.” On the road far in the distance I could see flashes that looked like they came from rifle fire. When I came back to the room Mr. Koriyama said, “It didn’t take long for them to drive us here so we must be circling around Fallujah. What we saw earlier must have been the fighting in Fallujah.”

Then I thought of the soldier who had told me that morning that he was going to Fallujah.

Taken to yet another place on the morning of the third day. Over those eight days we went to eight different homes in all; there must have been a kind of network of farmers who had offered up their houses for the purpose. And then the day came when the General promised we would be set free.

It was a hot day. We must have ridden in the car for an hour or so. When they took off the blindfolds and we looked around we saw trees in the far distance, but nearby there was nothing but a sandy road. Before us there were about a dozen men we didn’t know, holding pistols. They seemed to be saying that we weren’t going to

Mr. Koriyama added, “Hell, ‘Muslims are good’! Isn’t what you’re doing just the same as what the Americans are doing?”

I felt hope slipping away and almost started to cry.

We walked down the road for a while and came to a lone house with nothing around it. It looked to be a southern-style house, with a shingled roof and earthen walls. Have they sold us to a different bunch?—I worried. Ms. Takato’s anger did not let up.

“They call you Mujahideen (warriors of Islam), but you’re nothing but Ali Babas (thieves).”

Seeing her explosive anger, a handful of the men had troubled looks on their faces; they said, “Wait three days,” and left the room.

We made strong bonds but…

We spent five days in this room. The room itself was homier than the others, and the food was better. Twice a day they would bring us dishes made with expensive chicken. “We got it at the market,” they said. An old man with deep wrinkles on his face and a young man with beautiful eyes stood guard over us and took good care of us.

There were now no militiamen in our room so we were able to speak freely to each other, the three of us. We all like music, so we sang all the time. We each had our favorite golden oldies that popped up in conversation again and again. Ms. Takato had been in a band so she knew a lot of songs. She even gave us a medley of tunes by Pink Lady. All three of us sang The Crystal King’s “Daitokai” (“The Big City”) and H2O’s “Omoide ippai” (“Full of Memories”) together. But I didn’t get to sing very much because there were two people in the room who hated Yutaka Ozaki, my favorite, to the point of banning him . . . .

Around this time we started calling each other by different names. In

Pardon the strange example, but we even got to the point where we looked at each other’s crap in the toilet. The toilet was outside, and once you’d done your business in it you poured water to flush. But on the fifth day my business was too big and it wouldn’t go down the hole. We all called it the Bunkerbuster. Anyway it was big and it was nasty and I tried to push it down with an iron pipe, but it wouldn’t go in.

“That’s enough of that,” I thought, fleeing the toilet. I got back to the room with a grin on my face and I told them what had happened. So-ni bravely headed for the toilet, saying,”When I was in the Self-Defense Force my job was laying and removing land mines. I’ll go.”

He gave it his best, I’m sure, but when he came back, his face was a bit puckered. When Nahoko went it must have been a huge mess. We called the older of our two guards and asked him to take a look—it was a crazy situation. He found a stick and used it to stir while he poured water into the toilet—or something like that.

Being together twenty-four hours a day, we exposed our whole lives to each, so we were more than family. On the third and fourth days we talked about our loves and So-ni talked about his experiences as a truck driver. Nahoko and So-ni talked the most. But on the fifth day it wasn’t fun anymore.

Mornings we’d wake up at eight, bedtime was eleven. In the evenings we got our light from a lamp, and we had blankets and pillows. We made a conscious effort to get up and move around, but since we didn’t really have anything to do, we ended up sitting around most of the time. We went outside only to use the toilet. Nahoko started feeling unwell. I rubbed her shoulders and So-ni rubbed her feet and hands.

Despair and dispute

On the fifth day So-ni got a migraine so bad he couldn’t move for half the day. On the sixth day, the day we were supposed to be released, no one came. Nahoko began sobbing in despair. None of us said a word. At the time we had no way of knowing why our release had been delayed.

For my part, I tried to hold out as best I could, but on the seventh day, when Nahoko recovered, I grew sluggish and despondent. I couldn’t stand up and my head hurt. It was then that our two guards started praying for me. The three of us had gone from being captives to guests. Of course we were not free to do just anything we pleased; still, we came to understand the generosity of the Muslim spirit.

On the eighth day, the fourteenth of April, they finally told us they’d take us back to

It was in this house that we saw pictures of our families on Al-Jazeera. They were airing images of my older brother and Nahoko’s younger brother Shuichi with their heads down. One of the militiamen pointed to us and said, “Famous people.” This was the first time we realized what a stir we were causing in

After dinner the things they took from us at the beginning of our captivity were returned. The cameras and computers and money were missing, though. The aid supplies we had brought had all been opened, and the pencils and pens we were to deliver to the schools had all been broken. So-ni yelled, “You are all Ali Babas. Bring us our things by tomorrow morning, all of it.”

Nahoko was even more strident. “Everything we’ve been doing for the Iraqi people has been undone. You’re ruining your own reputation.”

The argument went on for two hours. Nahoko was the only one doing the talking, and she wasn’t backing down. “Isn’t there some other way? Isn’t there a way to fight without using weapons?” she asked. They were at a loss for an answer. Because a lot of Iraqis had in fact been dying in the war with the Americans. Their only means of fighting was the clumsy one of using weapons. I think it was only through the violent act of taking us captive that they could say to the world, “Look at what’s happening in Fallujah.”

The morning of the next day, the fifteenth, the man called Leader brought us the missing items. Even so, Ms. Takato’s computer and the three thousand dollars gathered in

Free at last

That afternoon we were taken in an ambulance to a mosque in

“What is this?” I was thinking, when we were brought into a room and our blindfolds were taken off; then I saw Kider Dia [romanization unconfirmed], the Iraqi who was speaking Japanese, and a man who was videoing the scene. This reminded us of our captivity and we asked him to stop, but he kept recording. The Al-Jazeera logo was on the microphone. Meanwhile another man came in and said something. Dia translated: “You’re free.” Then Dia introduced us to Abdul Salam al-Kubaisi, the spokesman of the Muslim Clerics Association, explaining, “This is the man who secured your release.”

But we were in a daze. We still could not believe what was happening. Meanwhile they proposed we drink a toast, but we still didn’t understand why. It wasn’t until we heard Ueda Tsukasa, chargé d’affaires ad interim in Iraq, say, “It’s a good thing you’re unharmed,” that we finally realized we had been set free.

After this we were driven to the Japanese embassy. Thinking that such a nice car would be an easy target, I kept my head down. We arrived at the embassy in about twenty minutes. We went into the building under heavy guard. We were probably in high spirits; certainly we were relieved. We got to see some NHK television and once again the gravity of our situation was apparent. At the embassy all three of us called our families. I was the only one who didn’t get through.

The three of us didn’t know what the militant group had demanded, or that the footage they had taken had been aired. The three of us joked how bad it would have been if they’d shown the video, but in fact that is exactly what had happened.

We couldn’t understand why our captors didn’t release us once we’d convinced them we weren’t spies and they’d had a chance to give the matter a lot of thought.

“It only makes them look bad, so why do they keep us hostage?”

When we got back to

After we’d calmed down a little, Nahoko asked chief

We had been called “Japanese army” and “spies” so many times that we believed our captivity was directly related to the deployment of the Self-Defense Forces. The ambassador answered immediately, “There can be no question of withdrawing the Self-Defense Forces from

When Nahoko heard this answer she burst into tears. The ambassador left the room without uttering a word.

We remembered something one of the militiamen had said right before we were released: “We’re looking for a different way to do things, too. Can you give us any advice?”

They, too, seemed hesitant. The reason we couldn’t think ill of them, no matter what, was that we had seen the reality in which every time you heard an airplane you trembled and worried about an air raid, and every time there was an air raid someone died. Had I been born in that country I might have taken up arms, too.

Takato and Imai at time of release

“When you get home, just be sure to apologize”

Around seven o’clock that evening questioning by the Japanese police began. Two hours each for Nahoko and me, one hour for So-ni. We were each questioned separately, without getting to see a doctor. “We want you to cooperate so we can apprehend the Iraqi criminals,” we were told, so we complied.

Two men from the Foreign Affairs Section of the National Police Agency were in charge of the inquiry. Nahoko and I were each questioned by one of them, then they interrogated So-ni. There were times when I felt we were under suspicion of something. They asked us about the size of the room we were held in, the layout of the rooms, the arrangement of the furniture, the surroundings, and made us draw a map. Remembering such things was the last thing we wanted to be doing at that time, but absolutely no consideration was given to our feelings.

And then the officers started to ask if we hadn’t staged the video, and I immediately responded in the negative. At the time, I of course didn’t know that there was a theory that it was a staged video.

The inquiry continued into the next day. Nahoko was questioned by the

We spent the night of the fifteenth in an apartment next to the embassy. I watched the BBC news there, and the top news story showed pictures of us. “What a big deal it’s become” I thought, taken aback.

The next day we flew to

Three hours to

In the hospital I was reunited with my big brother. “What a relief,” he said, shaking my hand.

“Everybody’s pretty stirred up back in

[1] The starred sentences are taken verbatim from an interview with Carol Picou. See here (accessed 28 November 2007). Picou ends her 1996 statement thus: “Come together and fight for your sons, daughters, your mothers and fathers, for the people over there now, and for the people of Iraq that are suffering from the contaminants left behind in their land.” [Tr.]

Translated by Scott Mehl, with the kind permission of the author and publisher.

PART 2 Appeal on Behalf of the Hostages to the Sara Al Mujahedeen

April 9, 2004

By the name of God

Brothers of Saraya Al Mujahedeen

Al Salam Alaikum

God blesses you for what is good for our nation, our prayer for God to remove this grief from our country.

We wish that you would receive this letter. God knows that it is honest letter, this letter is for God satisfaction and to inform you, what you don’t know about your Japanese lady prisoner Nahoko. She is, as we saw that in Al Jazera station, one of the three Japanese prisoners.

We don’t have any doubt that she and the other two Japanese will have gratifying care from you. Because our religion order that. And that is what we learned from our great grandfathers.

We are not writing this letter to evaluate what you have done, or what you planning to do. And also we are not writing this letter because we are supporter for coming of Japanese army either they are normal army or they are protect army to participate in rehabilitation of

The only purpose of this letter and the photos attached is to let you know that Nahoko is last person which should be taken as a hostage, in case you must take hostages. This Japanese lady was very desirous from May 2003 to be in

Brothers of Saraya Al Mujahedeen, in behalf of our self and many Iraqi orphan children, we entreat you to release the three Japanese hostages, specially Nahoko as she is was content with only bread to feed her self, while she was buying palatable food for our kids. She is good example for the love of Japanese people for Iraqi people.

If God wishes and you released those three Japanese you will give Japanese people good chance to do what we and you want. Japanese people were always in the friend’s side, in the Iraqi causes. While many of our brothers in religion and nation were watching only.

The imperative is for God

AL Salam Alaikum

Group of active Iraqi in orphan’s field

9/4/2004

PART 3 Grandmother’s Story (Hanada Chizue)

It was after 3 p.m. on April 20th when Noriaki came home. I greeted him quite calmly. That was because just at that time, Mr. Yasuda and Mr. Watanabe [1] were still being held captive, and knowing that there were families suffering just what we had been through, I did not feel it was right to rejoice extravagantly.

“I’m so glad, welcome home.”

Since he came home safe and sound, I have nothing more to ask for.

When he was taken hostage, it was hard for me to comprehend what was actually going on. I did wish, from the bottom of my heart, that I could offer myself as a substitute. I couldn’t truly believe that “Noriaki was home” until some time had passed after his return, and we had settled back into our usual life.

Before he headed out for

The night before he left, I rubbed my sobbing grandson’s body. Overcome by anxiety, regret, and self-recrimination, he didn’t know what to do with himself any more. I held his hand and said to him, “Come back alive. It’s important for you to believe that no matter what, you won’t give up on life.”

And I sent him off with a smile.

We try not to let Noriaki see the TV coverage of the backlash. Why did things turn out like this?

Imai and his grandmother, Hanada Chizue September 2005

[1] Yasuda Junpei, free-lance journalist, and Watanabe Nobutaka, a human-rights activist, were also safely released.

(Interview by Koshida Kiyokazu)

from Imai Noriaki, Why I Went to

Translated by Norma Field

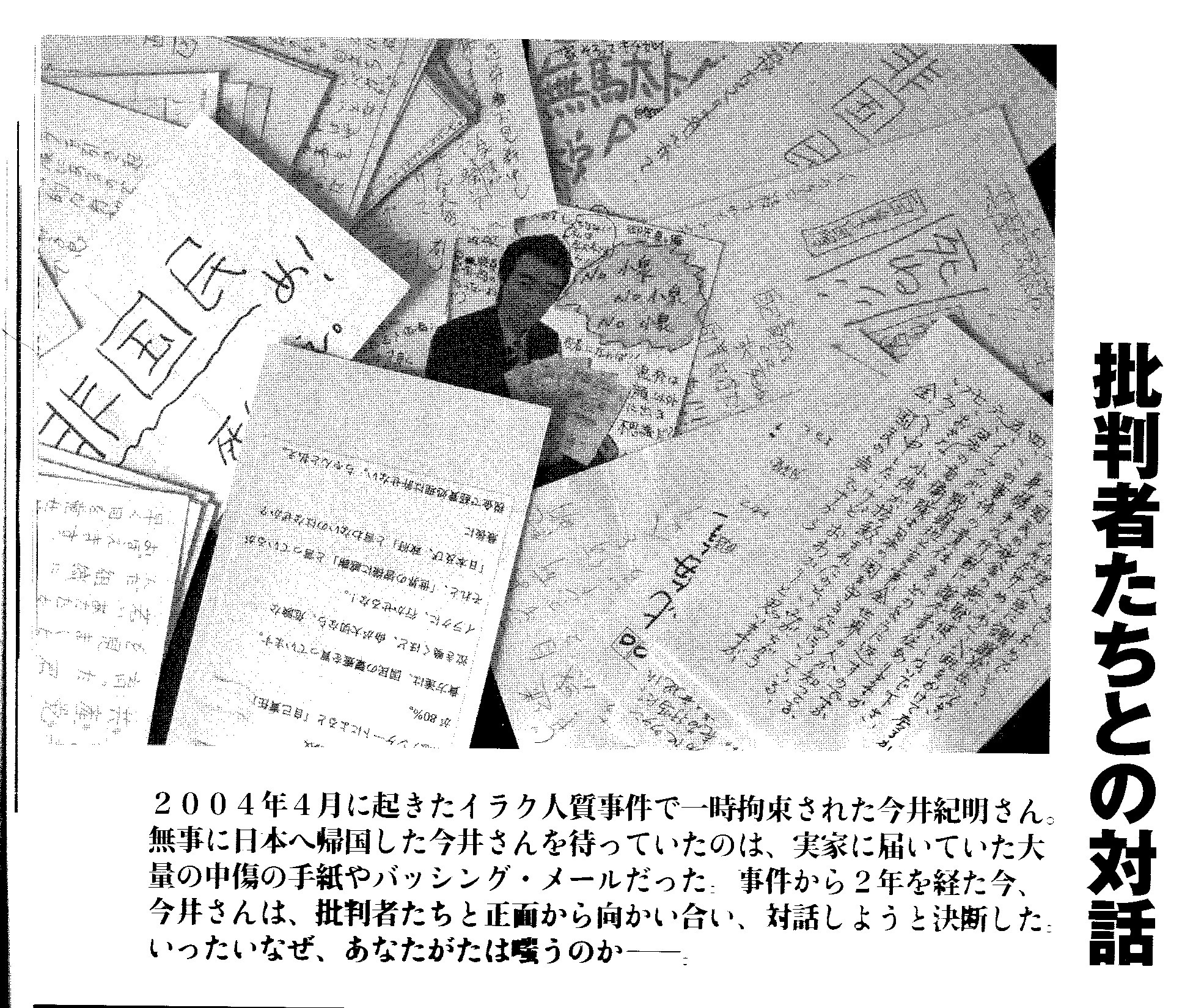

Part 4 Dialogue with My Critics

FLAMING (I): Dialogue with my critics

Having been kidnapped in

“Getting back to my subject, I need you to pay me 20,000 [yen]. You can fork it over from the sales or royalties of your book. Having caused all that trouble, Mr. Imai, you really ought to take responsibility for it. I work for X newspaper company. It’s ok if you confirm this with X newspaper company first. Just because you guys went [to

“You know, I’d managed to forget all about it, so why d’ya have to dig it up again? You’ve gotta be an idiot. Even celebrities get abusive comments thrown at them ( “die ” [shine], “gross “[kimoi]) on the net. Come to

Around 6 p.m. on February 8, when it was reported on a Yahoo website that I had released the abusive emails and letters sent to me during the hostage incident, the site was immediately swamped. In releasing these emails and letters, I intended to show the violence of anonymous verbal abuse. My weblog, which Yahoo had linked on their website, received approximately 200,000 hits within the space of three days. The sheer number of hits made it difficult to view the website with the letters. Moreover, 6,000 comments, filled with criticism and slurs, came in like a tsunami.

Within the space of three days, more than 250 messages were sent to the email address I had made public, and at the end there were up to 400. The excerpts above are from one of those emails.

In response to such criticism, I made my mobile number public and sought to engage in dialogue with my critics. As a result, I was able to speak with 13 people who called in.

Some of them were clearly angry when they called; nevertheless, they were all people with whom I could engage in reasonable discussion. Some even gave me useful advice. In contrast to the telephone conversations, there seem to be many people among those posting to the weblog who feel free to write abusively, and some of the people I talked with criticized such online comments by saying that “a lot of people are just baiting you.”

Comments on the blog

Here are some of the comments that were posted on the weblog.

“You mention having some sort of communication, dialogue or interaction with the people who sent in critical letters and emails with their real names attached. I think this is something a person can’t do unless he’s prepared to listen to others. I think you resigned yourself to accepting the criticism. That’s not easy to do. This time, if you had released those exchanges instead of the anonymous letters, I think you would have gotten your message across better.”

“I agree! I agree! “

“Use your head, asshole. “

The first comment is a reasonable response to the idea of publishing my exchanges with critics on the blog. However, the comments to that comment are obviously intended to make a butt of my “failure.”

“The kid’s blog name is ‘Underpants’

It’s all ‘Underpants,’ body and soul

You think I’m a guy who owns a ramen shop that went broke or something

You gotta be kidding

Don’t go lining up, you bastard

This is a lousy shop.”

“Might as well just turn you into ‘underpants,’ Imai “

“’Underpants’ = Imai, done! “

“You a fool?

You think that Underpants is going to use

a crappy, noob [newbie] word like flame?

You better start studying, asshole “

From about this point on, the user name “Underpants ” appeared almost every day, and it was sometimes used to refer to me. False posts, with people using my name, were also frequent. The following is one such example.

“472. Posted by Imai Noriaki 02/10/2006 15:12

I’m on my computer at last.

I apologize for this belated response.

I see there’re people posting comments like “die” and “get lost” again.

I have said this many times before, but please stop doing this sort of thing.

It’s pointless.

My patience is running out, and I’m going to get angry “

I hardly ever post a comment myself. If I do, it’s under the user name “Nori.” I have not posted throughout the current incident, but there are multiple posts on the weblog under the name “Imai Noriaki.” Why is this happening?

There have been many posts that show no intention of starting a discussion or engaging in reasonable criticism but rather take pleasure in the conflict itself. Still, from the beginning, about 40% of the posts were written from a serious standpoint, and the majority of the posts in the latter half could be described in this way.

Sociologists sometimes describe online bashing as “festivals” [matsuri]. Even in my case, there were many occasions in which people seemed to be taking recreational pleasure in the attacks. Here, I would like to write about the people who seemed to be enjoying the criticism or slander that was common in the early to middle stages of this incident.

Meeting my critics

How is it that people can enjoy slandering someone and participating in this sort of ganging up?

Since half a year ago, I have been trying to get in touch with people who sent in critical or abusive letters and emails. I have taken a look at the letters one by one, and replied to those that had a return address and a name. During the hostage incident, 104 letters arrived; less than 10 percent came with a name and a return address, and of these, only 3 addresses turned out to be real. I wonder what sort of people all the other anonymous writers are. How could they use such words as “shine ” and “kimoi “? As a human being, I was genuinely curious about this.

Before seeking out the anonymous, why not try to meet those with a “face,” I thought, and began to contact those who had been willing to identify themselves.

Takeda Yukio (alias) is a 50-year-old white-collar worker from the suburbs of

“I never thought I would really get a chance to meet you, Mr. Imai. ” Mr. Takeda took a sip of beer, smiling.

“I read a little of your blog. I thought those letters were horrible, really horrible. ” He seemed to be expressing a little sympathy toward me. It seems that he became aware of my blog after reading the email I had sent him.

“It wasn’t so much that I was critical of the incident itself; it was the argument of the media that got to me. ‘They were kidnapped because the government sent the Self-Defense Forces there. Since that is the government’s responsibility, the Self-Defense Forces should be withdrawn’ was a line of reasoning I couldn’t agree with. So I wrote a letter to the editor for the first time in my life.”

“It might be strange to say this right in front of you, but when a Japan Airlines flight was hijacked in 1977, Prime Minister Fukuda said that ‘the weight of a single human life is greater than that of the earth.’ Surely human lives are important, but I think accepting terrorists’ demands like that could lead to more lives lost in the future. So, I think we had no choice but to not pull the troops at that point. “

I nod over a sip of beer. Despite this, Mr. Takeda says, he was worried about us. If your family had been cool and collected, they would have been criticized for that, too, Mr. Takeda says slowly, as if choosing his words. The waitress had brought us some pasta, and we began to eat. Mr. Takeda ate a mouthful of pasta, before continuing.

“At that time, many Japanese people were truly worried for you. Although I didn’t know where you came from, I was worried. I thought some boys and and a girl from middle-class homes must have gone to

I asked him why he thinks we were criticized so much.

“I think it comes from the ‘toasting’ scene shown right after your release. We were thinking ‘they must have been hurt, not eaten anything. They must have had a hard time,’ but you all seemed much better than expected, and there was Ms. Takato saying, ‘I’d like to go back to

However, Mr. Takeda began, there had been a gradual shift in his opinions about us. He looked away, and then turned back to my eyes.

“After the incident, I heard news reports about why you and Ms. Takato went to

But, Mr. Takeda said, still looking in my eyes:

“Today, many youngsters like my daughter are said to be NEETs. If our society is going to crush young people pursuing a goal, its future can only be bleak. I’m worried that this might spell the end of Japanese society. “

Kurokawa Mitsuo (alias), 25 years old. He is the man who sent me the email at the beginning of this article. As mentioned in the email, he is a newspaper delivery man. After Mr. Kurokawa sent me the email, I gave him my number, to which he responded by calling.

“Why are you bringing up that incident again? Why do you want to rehash something that’s over and done with? “

These were his first words when he called me. He sounded more irritated than angry.

“I haven’t sorted it all out, but I don’t understand why you do things like this. I had to work holidays thanks to three people whose faces or names I didn’t know. I still haven’t been paid for the extra work. Are you an idiot? You ought to give me that money. “

This made me irritated too, but I asked him why he was turning his anger on me.

Mr. Kurokawa is a student on scholarship funded by the newspaper distributor, so he goes to college while working as a delivery man. The company is facing financial difficulties, which means he does not get extra pay for overtime. If he were to quit the job, he could no longer pay tuition. His parents will not pay it either, he says.

“Mr. Imai, of course everyone has something like their basic human rights, so you can do whatever you want, but I would like a little consideration for other people too. Yes, I was furious back then. Why was I having to go to work because of people like them, I thought. I would like you to understand that.” The anger was gone from his voice as he uttered these words.

“I don’t care about taxes or anything like that. I might even have gone over-the-top in demanding payment.”

Our phone conversation ended. While I was pondering what Mr. Kurokawa had just said, he called me again.

“I’m sorry about what I just said. Um, I hesitated a lot before calling. A lot of things have been sent to you anonymously, but there’s something wrong with that, isn’t there. There’re people who’re saying things like “stupid” and “die,” stuff that really goes against social morals, but they must feel like it wouldn’t be cool to have their identities exposed.”

Comments that can’t be considered “criticism “

“I had a look at the blog with the letters of criticism. When I first became aware of the blog, I trembled with rage. ‘A lot of taxpayer blood money was used to help these people come home, but they didn’t seem penitent at all!’ When I read the letters, I wanted to applaud the writers.”

This is an email sent by Tanaka Rieko (alias). I replied by giving her my number, and I was able to talk to her on the phone. Her soft-spoken manner, belied the impression I got from her email. I was surprised.

Ms. Tanaka remarks that she is especially unhappy with the way tax money was used.

“When I read the blog, I thought, what on earth is this guy doing? Why is he releasing this? The criticism is totally appropriate. He’s just playing the victim. “

She says, however, she thought some of the posts to the weblog were truly awful.

“I think I can tell the people who are truly angry from those who are just having fun. “

In fact, there were many serious comments, but there were also many abusive comments like “die,” “stupid,” “croak, ” and “gross. “

“736. Posted by –no 02/09/2006 03:20

You think ‘go and die’ is a piece of abuse?

I think it’s a piece of advice. “

Can we call posts like this “criticism “? Why do they use words you could not say to someone’s face, or, if I quote one of the people I spoke to on the phone, words that “are socially unacceptable, that cannot be used in human relationships?”

[1] This post reflects the style of “2-Channel” (nichanneru) discourse. 2-Channel is said to be the largest internet forum in

[2] “Personal responsibility” is the translation for jiko-sekinin, a neologism that gained instant popularity during the hostage crisis. The hostages had chosen to go on their own responsibility and accordingly were owed nothing by the state. Such reasoning has proven to be broadly useful in the era of neo-liberal privatization.

* * *

Shizen to Ningen [Nature and Humanity] 4, April 2006, Vol. 118 (17-20), translated by Ayumu Tahara with the kind permission of the author and publisher. Footnotes by the translator. Part two of this article, published in the May issue, takes up other victims of abusive treatment on the Internet.

PART 5 FROM THE DIARY OF IMAI NORIAKI

September 24, 2006

The things that won’t disappear

Now that two weeks have passed since 9/11, here are some things I’ve been thinking about.

These days, I can’t seem to remember what I did during high school. Actually, it’s not just these days. I think it started a little after the incident. Of the things that happened to me 2½ years ago and leading up to that time, I don’t have very distinct memories. I don’t even understand why. If someone told me to recount what’s happened in the past 2½ years, I probably could, even in detail. Before that, my mind goes blank. Of course, I can’t recall what I was doing on 9/11. The only thing that remains in my mind is the fact that I was against the bombing of

Ever since the hostage incident and my time in

But I think I’ve really settled down since I got into college. The two years before then, doing odd jobs and what not, I was living a pretty unstable life without clear direction. Since coming to Beppu, I’ve been lucky in my friends and environment. How should I say this, I feel like I’m recovering myself bit by bit. Of course, I don’t go out of my way to remember things from the past, but I can feel myself coming back, I think.

And now, I’m thinking about

I’m going to stop here. I just want to start confronting the things that I had stopped thinking about. If you ask what I can do without actually going to those sites, then the answer is, only this.

[a tiny sampling of ] Comments

31) Posted by “A” 10/02/2006 20:35

It takes two-and-a-half years to face your own problems.

Humans are like that, aren’t they.

Because they’ve never been to Iraq, because they were to no small degree shocked by the war, and because they don’t want to change their way of thinking, there’re people who want to beat up on the signifier “Imai.”

For no particular reason or meaning at all, because it’s easier to beat up on someone else than to change yourself.

They’re just like you.

32) Posted by “Junichiro” 10/04/2006 8:16

Well it’s because Imai’s a loser.

Don’t you feel like kicking the shit out of him sometimes?

You get it, don’t you. Even you.

37) Posted by “mu” 10/05/2006 23:25

I thought you hadn’t been on site recently.

So you’re saying that even without going to the actual site, you can say what you want?

So you’re saying that getting things through the media is enough?

Then what you did in the past was pointless after all.

39) Posted by “It’s just my personal opinion” 10/05/2006 23:28

I feel like what you’re fussing about is just a little off.

You’re weirdly focused on “depleted uranium shells.” Why not be concerned about “all arms”?

You talk about “the danger/safety of depleted uranium shells,” but guess what. All weapons are basically dangerous.

66) Posted by “tns” 10/20/2006 02:49

A carefree student, huh? You lucky son of a bitch, eh?

Your book been selling well? Do something with that money so I can have another laugh. How about infiltrating the North?

67) Posted by “Norisuke” 10/20/2006 08:20

You want me to infiltrate

There’ll be 100,000 deaths from starvation.

Damn murderers!

68) Posted by X 10/20/2006 10:59

How d’ya get to the North? D’ya hafta go through

69) Posted by Norisuke 10/20/2006 12:26

From

You go through dangerous territory by choice.

That country’s got a weakness for money, too, so they’ll do anything for you.

(See here, accessed 20 December 2007)

February 17, 2007

Looking at the present, the past, and the future

I was finally able to get some sleep last night. Up until yesterday the week was insane. I had to work 9 hours a day, then do all kinds of things related to BEPPoo!! [1] Even though it’s a lot of work, I feel like we’re able to give it our all because there’s the pleasure of feeling like we’re somehow able to create our own media. Bit by bit, I hope that our little group can do things that link up with the revitalization of the town of

Changing the subject–I got a letter the other day from somebody I know who’s a hairdresser. She’s turning 30 this year, and she tells me she’ll be quitting her job. The reason is that her health isn’t great. I used to talk to her a lot, and she’d told me that she’d almost died once, and that she had a chronic illness that didn’t seem to get better. And now, all of a sudden, this decision to quit her job.

In spite of it all, she says she’s going back to her hometown in eastern

I’ll turn 22 this year. Ordinary college students on track would be graduating this year. But I have many friends around me who came in last year as new first-year college students, ranging in age from 21 to 25. Most had jobs before coming to college; others had part-time jobs and all kinds of experience before coming to APU [

I want to become someone who’s useful in all kinds of situations. I’d still like to do the kind of work I used to do with an NGO. That’s because even if violence between people is inevitable, I want to contribute to decreasing the ultimate violence of war and armed conflict. If I look at what NGOs are doing, though, I can see that they aren’t able to prevent war or armed conflict but rather, they’re just dealing with things after the fact. Sure, it’s necessary to have all kinds of people go out into the world and help others in need. But we don’t seem to be able to control the violence of killing that occurs beforehand. To the question, what are we supposed to do, then, there’s no answer. The fact of the matter is I end up feeling powerless before the contradictions inside me.

But you know what? Even if my current life leads to my joining a firm or company, I want to continue doing what I believe in, even if little by little. The power of one person amounts, in the end, to something like dust. Yet, as the saying goes, “When even dust accumulates, it forms a mountain,” I want to do even a little bit toward putting an end to extreme violence. Different people having different opinions is a given, but that shouldn’t lead to killing each other. This is what I’ve believed in ever since high school. It’s because I still think about that that I’m doing BEPPoo!! here with my friends.

If you look at BEPPoo!! from outside, it is admittedly still incomplete as a media form. Even so, in just one year, our staff of 7, 8 very busy people managed to accomplish something. I want to quit my part-time job by this summer and concentrate on this.

Although Beppu is a small town of 120,000, it has the highest ratio of foreigners to Japanese after

It’s hard to see into the future, and for this very reason I don’t want to avert my eyes. There are a lot of uncertainties, but nothing will get started if we stop to list all our complaints and dissatisfactions. What we can do before we start with our complaints and dissatisfactions is to look at ourselves. Something will surely get started from that. Let’s not give up, while we look at the present and the past, and the future.

Comments

1) Posted by “Kataoka Kazuyoshi/Sukichi” 02/17/2007 21:53

Jesus is your true friend, who will help you in times of trouble. I went to Aeon Miyazaki Central Movies and watched Dream Girls.

Everybody, let’s go look for a dream, let’s look at the thing that only you possess, the thing that the Lord has given only to you.

It is something buried inside you like a diamond, if you were to find it, whether it be big or small, however small it is, let’s believe in it. Let’s protect this diamond,

*Patience, yeah, patience, yeah, patience, patience shall take you to where you’ll be surrounded by so many people who praise you, yeah.* [Text between asterisks in English in the original.]

The seed of the sidewalk, the bird pecks at

The seed of the rocky land withers in sunlight

The seed of the thorns is crushed and sealed

The seed of the cultivated fertile lands, multiplies a hundred-fold

2) Posted by “kkkyyy” 02/18/2007 00:55

Please don’t give up and good luck.

Your trying to revive a countrified town like Beppu is Nice!!

4) Posted by “Haruhi” 02/18/2007 11:17

Get a life

Playtime is important

[1] A portal website for the citizens of Beppu, Oita Prefecture, started up and maintained by Imai and a small group of fellow students.(See here, accessed 20 December 2007)

Translated by Ariya.

December 16, 2007

Even though my hand’s shaking

… For the past 3 years and more, I’ve been watching my friends go where they want, do what they want. Every time I hear their stories, I think, “Wow—that’s incredible. I couldn’t do that, though.” But I’ve decided to try to be more honest with myself.

That’s because I really do want to go out into the world and see and learn a lot of things. I want to have the experiences you can only get while you’re in college. And I want to turn them into something that’ll be useful for other people in the future. Without noticing it, I’d given up on that kind of hope, but after all, if I don’t move forward, I won’t know what I’m living for. After all, I survived, so I’ve got to move forward. This life was given to me, it’s a life that was saved for me by others.

For over 3 years now, I’ve been restricting my freedom of action. I’ve tried to go only to safe places, to places where I could have fun. But in the end, I have a feeling I was avoiding looking at the big problems facing society. True, I’ve paid attention to what’s going on, I’ve participated in stuff like elections and whatever concerns

Right now, I want to follow up on Muslim people. I want to learn what kind of people the believers of Islam are. There’s a ton of stuff I want to know. I can’t go on shrinking back. I have to admit that it’s scary to go overseas. Just thinking about it makes my hand shake uncontrollably. But if I don’t take action, I won’t change and the world around me won’t change.

Tomorrow’s a training session for [incoming members of] BEPPoo!! It’s going to be busy but I’m going to do my best and enjoy myself.

(See here, accessed 20 December 2007)

Translated by Norma Field

***

Scott Mehl is a graduate student of Comparative Literature at the

This article was prepared for Japan Focus. Posted on December 29, 2007.