Gendered Labor Justice and the Law of Peace: Nakajima Michiko and the 15-Woman Lawsuit Opposing Dispatch of Japanese Self-Defense Forces to Iraq

Tomomi YAMAGUCHI and Norma Field

Introduction

In 2004, then Prime Minister Jun’ichiro Koizumi, in response to a request from the United States, sent a contingent of 600 Self-Defense Force troops to Samawa, Iraq, for the purpose of humanitarian relief and reconstruction. Given that Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution eschews the use of military force in the resolution of conflict, this was an enormously controversial step, going further than previous SDF engagements as part of UN peacekeeping operations, which themselves had been criticized by opposition forces as an intensification of the incremental watering-down of the “no-war clause” from as early as the 1950s.

Many citizens, disappointed by the weakness of parliamentary opposition since a partial winner-take-all, first-past-the-post system was introduced in 1994, and frustrated by a perceived lack of independence on the part of the mainstream media, have taken the battle to the courtroom. As with Yasukuni Shrine suits, singly or in groups, with and without lawyers, they have been suing the state for violation of the Constitution in deploying SDF troops to Iraq.

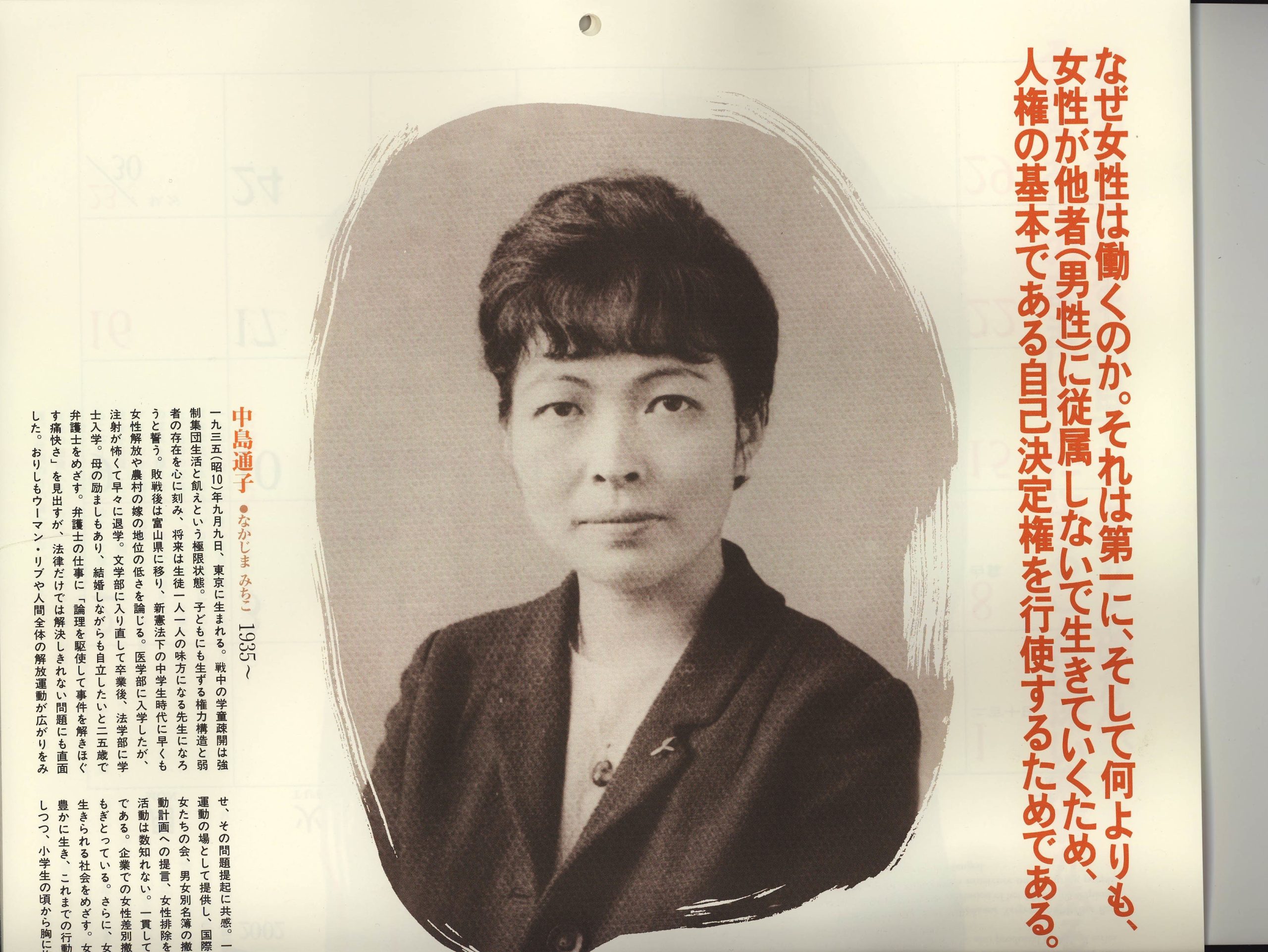

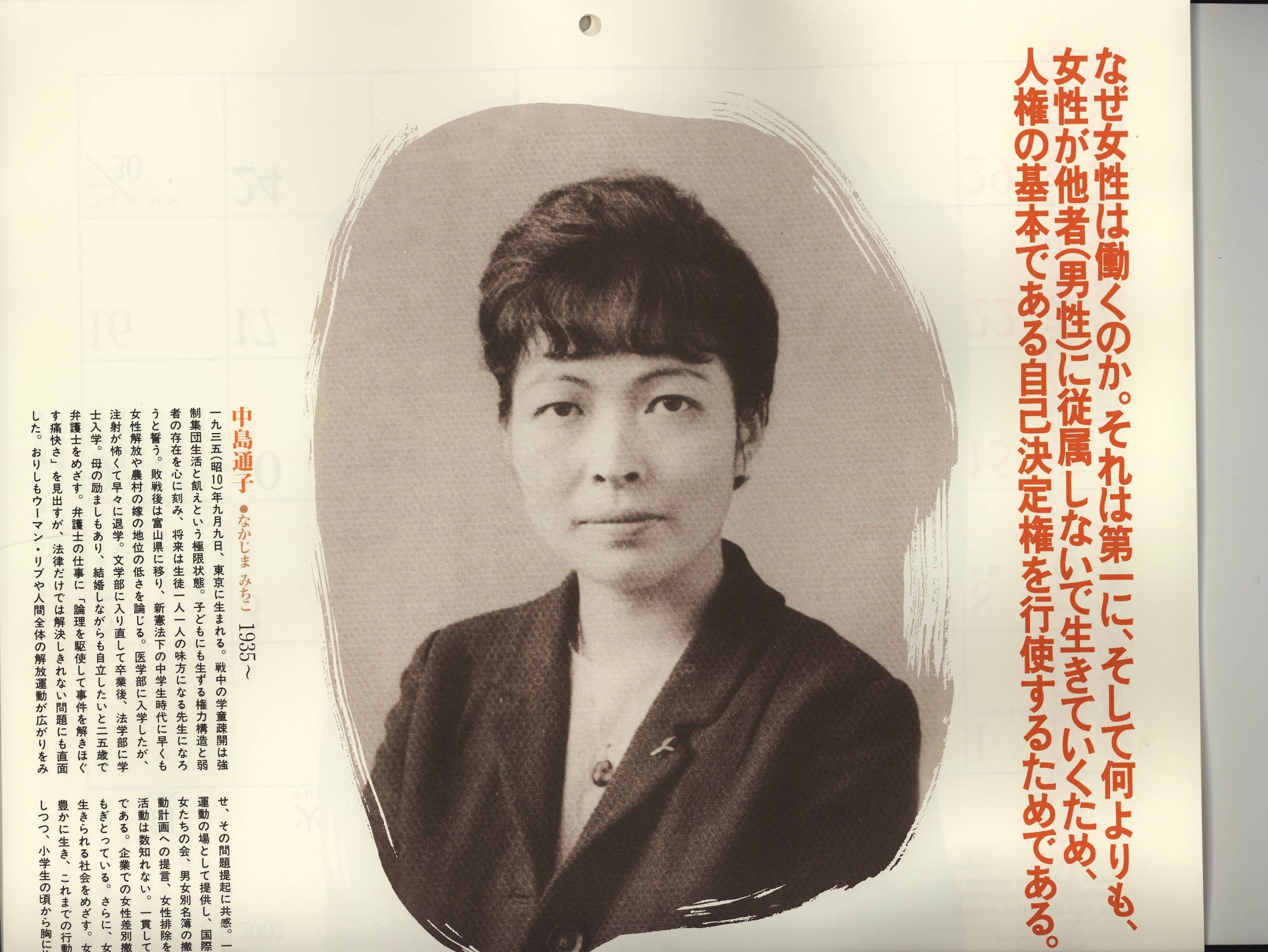

Nakajima Michiko from the 2002 calendar, To My Sisters, a photo of her from her student days at the Japanese Legal Training and Research Institute. A larger view of the same page can be viewed here.

Nakajima Michiko, a feminist labor lawyer, led one such group of plaintiffs, women ranging in age from 35 to 80. Each of the fifteen had her moment in court, stating her reasons, based on her life experiences, for joining the suit. This gave particular substance to the claim that Article 9 guarantees the “right to live in peace”—the centerpiece of many of these lawsuits, a claim that seems to have been first made when Japan merely contributed 13 billion dollars for the Gulf War effort. What might the “right to live in peace” mean, for individuals and for the collectivity—not just in Japan, but the world? The women’s invocation of their histories is key to claiming standing: like the U.S., and unlike many European countries or South Africa, Japan lacks a constitutional court, which means that abstract claims of constitutional violation cannot trigger judicial review; plaintiffs must show that they have sustained concrete injury to legally protected rights and interests.

Given the almost, though not total, reluctance of Japanese courts to exercise judicial review with respect to prime ministerial visits to Yasukuni Shrine, it is not surprising that judges have been unwilling to acknowledge a claim for a constitutionally guaranteed right to “live in peace.” And yet, the elaboration of this right, the right to develop as a human being without “the fear of having to kill or be killed,” is surely a logical outcome of Article 9 and the democracy set in motion with the adoption of the postwar Constitution.

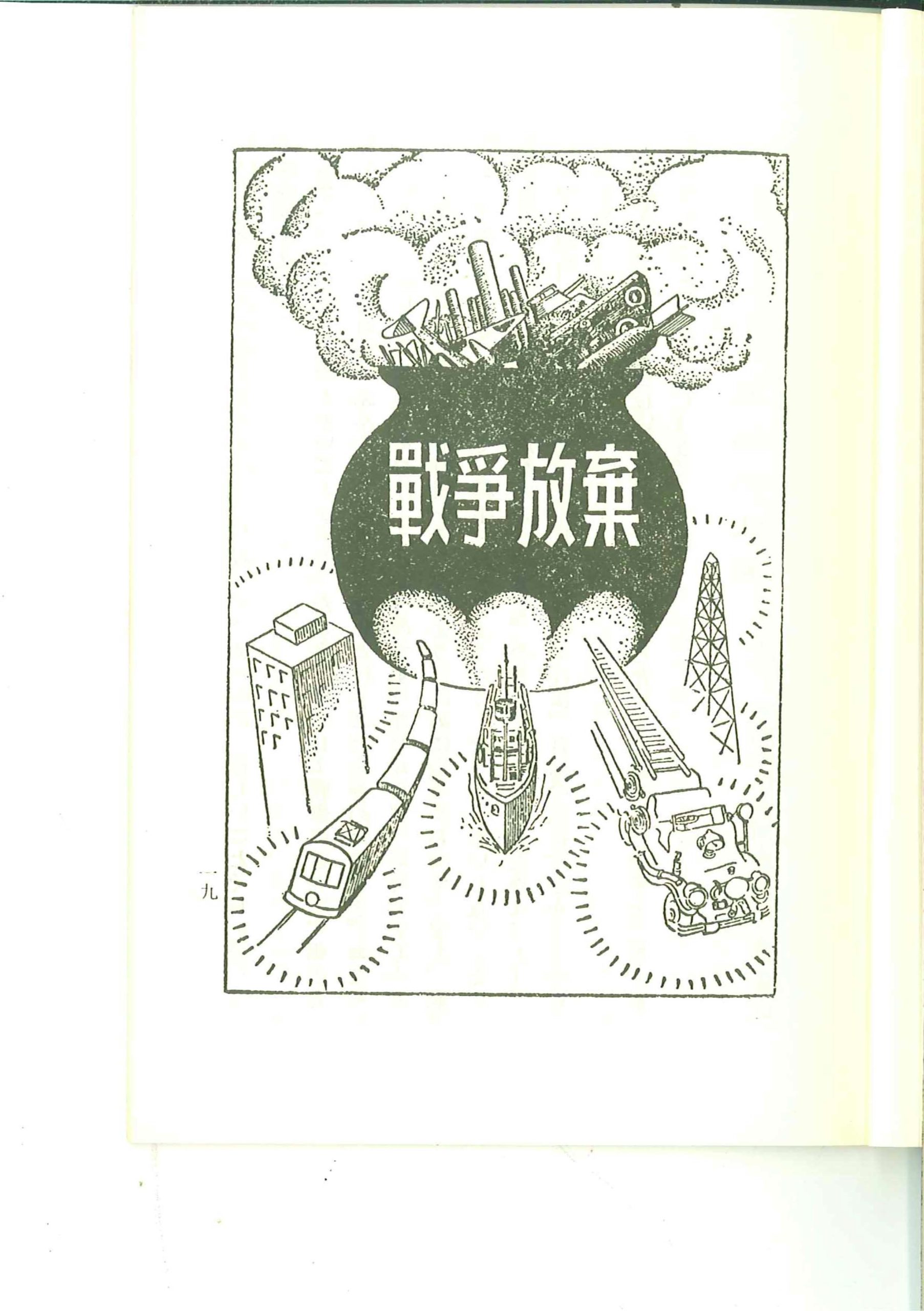

Story of the New Constitution cover

It is an outcome that is not captured by discussion of the origins of the Article (e.g., as trade-off for keeping the emperor, stated in Article 1), much less by the unimaginative arguments about the need to become a “normal,” i.e., armed nation. Nakajima’s still palpable pleasure in the illustration of tanks and bombers going into a cauldron and trains and fire engines and buildings coming out the bottom in “The Story of Our New Constitution,” the supplemental social studies textbook issued by the Ministry of Education in 1947, sixty years after she encountered it in junior high school, is but one indication of the enthusiasm for peace unleashed by war’s end and given shape by the Constitution.

“Thus We Appealed: A Record of the Case of the 15-Woman Group Demanding an Injunction Against the Dispatch of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq” is a text combining the narratives and legal arguments presented by the fifteen women plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed in Tokyo District Court on August 6 (Hiroshima Day), 2004 together with the judgment, delivered in May 2004. The translation of this text, of which a revised version is presented below, was undertaken in preparation for Nakajima Michiko’s visit to the University of Chicago in May 2007 as a guest for a course entitled “Postwar Social Movements in Japan” and the parallel lecture series, “Celebrating Protest in Japan.” [1] Because of Nakajima’s untimely death in a diving accident a scant three months later, Tomomi Yamaguchi and Norma Field, the authors of this introduction and co-organizers of the course and the series, would like to pay tribute to Nakajima by providing a brief sketch of her lifelong activism. It was the historical extent and nature of Nakajima’s activities that made her the starting point of their course planning.

Thus we appealed, cover

Nakajima Michiko was a pioneer who became one of the most renowned feminist attorneys in Japan with a specialization in labor law. She undertook a number of cases involving discrimination against women in employment and won many of them, including the very first supreme court decision in Japan on gender discrimination in employment, which found discrepancy in mandatory retirement age for men and women to be illegal (Nissan Motors Co. Case, 1981). Throughout her career she was active in the Japan Bar Association’s committee for equality for the sexes, and as a feminist practitioner, she took on many divorce cases.

Her history as a feminist and peace activist goes back to her high school days. Born in 1935, she experienced the war as a child who suffered from the loneliness of compulsory evacuation, hunger, and the terror of air strikes. Her first involvement in activism was with the Wadatsumi-kai (memorial society for students killed in the war) as a high school student in Toyama Prefecture. She then participated in Ampo (the movement against the US-Japan Security Treaty renewal of 1960), provided legal support for members of the Zenkyoto (All-Campus Joint Struggle Committee) radical student movement of the late 60s, and then became involved in the Women’s Liberation Movement in the early 70s. While actively participating in demonstrations and actions, she conducted legal counseling sessions at Lib Shinjuku Center, a communal center formed by young women’s liberation activists in Shinjuku, Tokyo.

In 1975 she formed a Tokyo-based feminist group, Kokusai Fujin-nen o Kikkaketoshite Kodo o Okosu Onna-tachi no Kai (International Women’s Year Action Group) with other feminists, including Upper House representatives Ichikawa Fusae and Tanaka Sumiko, media critics Yoshitake Teruko, Higuchi Keiko and Tawara Moeko, and many other women ranging from workers, teachers, housewives, to students. Among many significant achievements of the group, the most notable one was its protest in 1975 of an instant ramen noodle TV commercial designating a female figure as the one who cooks versus a male as one who eats. The commercial ended up being cancelled, and the protest is still remembered as one of the most influential of feminist protests. Nakajima also made her office available for use as a space for various feminist activist groups.

Becoming keenly aware of the need for a Gender Equality Law in employment through her experiences as a feminist lawyer and activist, Nakajima started a new group in 1979, Watashitachi no Koyo Byodoho o Tsukuru Kai (Group to Create Our Own Equal Employment Law), with the Action Group members and others. The group argued that both women and men should work equally, and that both should lead more fully human lives. The movement resulted in the 1985 Equal Employment Opportunity Law, a law that turned out to be a major disappointment for feminists. Nakajima, together with other activists, immediately started a new movement to change the law. Their activism resulted in the revision of the law in 1999 and in 2007. Although the revisions showed significant improvement from the earlier version insofar as employers were held responsible for preventing sexual harassment in the workplace and for prohibiting indirect discrimination, deficiencies remained and new distortions appeared, reflecting Japan’s increased adoption of neo-liberal principles. This in turn prompted Nakajima to focus on issues related to part-time and temporary workers. She was dismayed about the labor situation in Japan becoming more unstable and exploitative for both women and men.

Her peace activism paralleled her labor activism. In 1980, with the landslide victory of the Liberal Democratic Party in the general election and the increased dominance of conservative political forces, Japan seemed to have embarked on an accelerated course to become a “normal” nation capable of participating in war. Given this situation, Nakajima, along with feminist colleagues such as Yoshitake Teruko and Tanaka Sumiko, established a new feminist peace group, Senso e no Michi o Yurusanai Onna-tachi no Kai (Japanese Women’s Caucus Against War) in 1980. She was a strong supporter of the efforts leading to the Women’s International Tribunal on Japan’s Military Sexual Slavery (2000) as well as in establishing the Women’s Active Museum in accordance with the will of Matsui Yayori, who spearheaded transnational efforts to hold the Tribunal and bequeathed her estate to such an endeavor before her untimely death in 2002. Nakajima was deeply worried about the fate of Article 9 and active in various efforts to safeguard it. She made sure to cast her absentee ballot for the Upper House elections in advance of her fateful trip to Hawai’i in late July. Let us hope that she heard the news about the stunning defeat dealt Abe and the LDP before her tragic death although of course, she would have been the last person to slacken her efforts after an election.

Selling copies of the collectively produced book about the Women’s Action Group ( The Path Opened by Women in Action) with fellow member Kobayashi Michiko. Nakajima center.

Fukushima Mizuho, head of the Japan Social Democratic Party and former member of the Women’s Action Group, read a highly emotional and moving eulogy at Nakajima’s memorial service, which she later posted on her blog. There, Fukushima declared, “Nakajima Sensei did a wonderful job of teaching generations of women coming after her. Without her, I would not have become a lawyer dedicated to abolishing gender discrimination.” It was meeting Nakajima as a college student that attracted Fukushima to the law. Fukushima’s invocation of Nakajima’s cases involving Nissan Motors, Japan-Soviet Books (Nisso Tosho), Sanyo Realty (Sanyo Bussan), Showa Shell, Japan Iron and Steel Federation (Nihon Tekko Renmei), Imperial Pharmaceuticals (Teikoku Zoki Seiyaku), or Okinawa bus guides from a list “too long to enumerate” reads like the poetry of gender and labor justice, addressing not only pay inequality and retirement discrimination but mandatory transfer policy, which Nakajima would come to see as injurious to men as well.

Like the young women in Fukushima’s account, Tomomi Yamaguchi was encouraged and educated as a feminist by Nakajima. She met her while a graduate student doing field research focusing on the Women’s Action Group. Listening to her endlessly fascinating stories, she learned a history of activism that she had not previously encountered. Nakajima tirelessly supported and inspired her, encouraging her to pursue her interests in feminism and to become a scholar with a deep commitment to activism. Yamaguchi knows that Nakajima’s influence will continue to guide her and others who follow in her footsteps.

Despite her knowledge, experience, and distinction as a professional and an activist, Nakajima was a strong believer in the ideology of “hiraba,” the level field. She was someone who always listened to and talked seriously with people regardless of their age, knowledge, or experience. This was repeatedly demonstrated in the openness and earnestness with which she engaged in discussion with undergraduates at the University of Chicago during her visit in May of 2007. This characteristic carried through to her professional practice, which Field had the opportunity to witness directly. The personal and the political were clearly connected in her mind and her actions. No detail was unworthy of her attention; she seemed to have an intuitive understanding of how shifts in the elements of daily life, both material and psychological, could make existence tolerable or intolerable. Still, devoted as she was to her profession (understanding, for example, the importance of divorce for many women clients), she also wished that she could be freed of the burdens of maintaining a practice so as to more freely devote her expertise and energies to the causes that held her attention. She identified herself as an anarcho-syndicalist: both parts are important, she emphasized to Field two years before her death

Nakajima was well aware of the continuities in her life. When news broke of the three young Japanese taken hostage in Iraq in 2004 and threatened with being burned alive unless the Japanese Government withdrew the Self-Defense Forces from Samawa, she immediately rushed to sit in at the Prime Minister’s residence. She told Field that seeing the picture of the youngest, Imai Noriaki (then 18), she had said to herself, “That’s me, fifty years ago!” [2]

It is unsurprising, then, that she should have taken steps—with other women—to file a lawsuit demanding an end to the dispatch of Self-Defense Force troops to Iraq. The suit ended in defeat at the district court level in May of 2006. She was not surprised, though angered by the judges’ refusal to show the semblance of engagement. The record produced here bears witness to her continued resolve.

Nakajima’s commitment to peace and justice gave coherence to all her activities. Indeed, peace and labor justice were mutually indispensable to her vision of a desirable society. What she sought was not for women to become men and to dedicate themselves, mind, body, and soul to work, but for women and men to have richly human lives—each working fewer hours, thus ensuring work for all and a fulfilling existence for each. What kind of society would it take for labor to be organized in such a way? One thing is certain: it would have to be a society that had renounced war as a source of security, economic growth, and collective identity.

[1] For a podcast of her public lecture at the University of Chicago on May 4, 2007, with comments by anthropologist John Comaroff, please go to this website. For a transcript of Nakajima’s classroom interactions at the University of Chicago, please see here. Nakajima’s publications include Onna ga hataraku koto o mo ichido kangaeru [Reexamining “women at work”], 1993; Kodo suru onna ga hiraita michi: Mekishiko kara Nyu Yoku e [The Path opened up by women in action: From Mexico to New York], jt. Authorship, 1999; andOnna ga hataraku koto, ikiru koto [For women to work, for women to live] 2002.

[2] A podcast of Imai’s public lecture may be found here.

Tomomi Yamaguchi teaches anthropology and Japan Studies at Montana State University-Bozeman. She is currently working on a book on the Women’s Action Group that Nakajima Michiko belonged to and researching the current backlash against feminism in Japan. Norma Field is immersing herself in Japanese proletarian literature, working toward an anthology with Heather Bowen-Struyk from University of Chicago Press and a book on Kobayashi Takiji. Yamaguchi and Field are collaborating with staff and students to produce a website on social movements in Japan, beginning with materials prepared for the course and Celebrating Protest series referred to in the introduction. This introduction was written for Japan Focus and posted on October 20, 2007.

Thus We Appealed: A Record of the 15-Woman Group Demanding an Injunction against the Dispatch of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq

Preface

Even now, more than three years after the start of the invasion of Iraq, chaos reigns within the country, the number killed and injured continues to rise, and because of the unrest, civilians are forced to live a difficult life. Anguished as we were by America’s unjustifiable exercise of force, once the Koizumi cabinet reached the decision to dispatch Self-Defense Force troops to Iraq, we decided to pursue the question of the unconstitutionality of the action in court.

In Tokyo, individual citizens were already filing suits in court, at the rate of one a day, and class action suits were being filed throughout Japan.At a point where, despite our sense of urgency, we could not resolve to act individually, we obtained the cooperation of a lawyer, Nakajima Michiko.As a group of fifteen women, we were able to participate in the lawsuits arguing the “unconstitutionality of the dispatch of troops to Iraq.” We filed our suit two years ago on August 6,Hiroshima Day.

Faced with a judiciary that has consistently evaded constitutional findings, we regretfully decided that the only form our suit could take was that of a civil action seeking an injunction against the dispatch of troops and compensation for personal damages. Convinced that the Constitution recognizes citizens’ right to live in peace, we each submitted, on two occasions, written statements detailing personal, physical, and mental injuries and demonstrating the importance of peace to our wellbeing. In spite of this, the Court reached its decision without examining the evidence, calling witnesses, or examining the Plaintiffs themselves.

The decision handed down in May of this year [2006] stated that “No statute exists stipulating the right to live in peace, either as a specific right or as a legally protected interest” and rejected our demands and dismissed our case. For more particulars, please refer to “Comments on the Decision” below.

The statements printed in this booklet represent the core of each person’s written statement as revised for the concluding hearing in March, in which the Plaintiffs stood up, one after another in relay fashion, and read their pieces over the course of thirty minutes.

We asked the Court for a decision that might advance, by even one step, the cause of securing the right to live in peace, but sadly, this was not realized.We feel anew the limits of the Japanese judiciary with its low degree of independence from the government.We take pride, however, in having asserted our dissent.

June 2006

The Docket, Submitted Briefs,and Plaintiffs’ Statements

1. October 21, 2004 Petition Statement Statements of 3 Plaintiffs

2. December 3, 2004 Preliminary Brief (1)-1 What is occurring in Iraq and what the Self-Defense Forces are doing there: The actual conditions of the Iraq War and its illegality under international law

Preliminary Brief (2) Injuries sustained by Plaintiffs: Right to live in peace and personal rights Statements of 3 Plaintiffs

3. February 18, 2005 Preliminary Brief (1)-2 What is occurring in Iraq, what the Self-Defense Forces are doing there: The actual conditions of the Iraq War and its illegality under international law

Preliminary Brief (3) The unconstitutionality and illegality of the dispatch of the Self-Defense Forces: The recklessness of the cabinet in destroying constitutionalism

Statements of 3 Plaintiffs

4. May 13, 2005 Preliminary Brief (2)-2Injuries sustained by Plaintiffs

Preliminary Brief (4) What Japan ought to do for Iraq: What constitutes true humanitarian aid activities?

Statements of 2 Plaintiffs

5. July 14, 2005 Preliminary Brief (5) Seeking Explanation

Submission of Proposed Evidence 1

Statements of 2 Plaintiffs

6. September 8, 2005 Preliminary Brief (6) Statement of 1 Plaintiff

7. November 17, 2005 Submission of Proposed Evidence 2

January 24, 2006 Court ruling (petition for the examination of witnesses and Plaintiffs dismissed)

8. February 2, 2006 Statement concerning court procedures

9. March 16, 2006 Final Preliminary Brief Statements of 2 attorneys

Statements of 15 Plaintiffs

10. May 11, 2006 The decision

Heisei 18 (2006) March 16

Heisei 16 (2004) Number 16912: Case Demanding an Injunction against the Dispatch of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq

Plaintiff: Ishizaki Atsuko and 14 others

Defendant: The State [the government of Japan]

Tokyo District Court of Law, Civil Affairs Deliberation 15 System B

The statement of attorney Nakajima Michiko

Your Honors, can you not hear them: the voices of pain and sadness coming from the Iraqi people, and the footsteps of war that are approaching Japan? The plaintiffs and the attorney before you can hear them clearly. We have brought this lawsuit with the urgent desire of stopping this development. It is truly a shame that the court has not admitted the testimony of witnesses and Plaintiffs, but the Plaintiffs have submitted extensive documentary evidence. We ask that the court read all the documentary evidence and take the time to confront, in silence, this photograph of a bloodstained girl. And please do not hand down a decision along the lines of the Kofu District Court decision, as argued by the State. That self-abnegating decision might as well be deemed a suicidal act on the part of the Court.

The cover of DAYS Japan, inaugural issue (April 4, 2004).

Additional note, December 14, 2020:

At the time we posted this article in 2007, we shared in the enthusiasm felt by those concerned with peace and human rights for DAYS Japan, the monthly magazine dedicated to photojournalism. In December 2018, however, the magazine’s founder and then-president, Hirokawa Ryuichi, was accused of sexual harassment and violence by seven women. More former workers of DAYS Japan and former assistants of Hirokawa came forward and accused Hirokawa of sexual assault, sexual harassment and workplace bullying. It became impossible to ignore the contradiction between the magazine’s coverage of human rights issues and Hirokawa’s behavior, deeply injurious to the human rights of its workers. DAYS Japan published its last issue in March 2019, and dissolved the company. See Tamura Hideharu, “Blowing the whistle on sexual violence by Hirokawa Ryuichi, a prominent Japanese human rights journalist” as well as the report of a third-party investigative committee [in Japanese].

The matters on which we request the Court’s decision may be broadly separated into the following two categories:

First, we assert that the deployment of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq is unconstitutional and illegal.

The majority of decisions in peace lawsuits avoid ruling on the constitutionality of the contested issue. We accordingly ask that the Court not casually sidestep the issue of constitutionality. Under the separation of powers, the judiciary is given the authority to review the constitutionality of the actions of the Diet and the government. A representative democracy is often unable to check laws and government actions that are at odds with the people’s will. This is exactly why the judiciary’s authority of judicial review is indispensable. In the cases brought against Prime Minister Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine, constitutional violation has been found numerous times, even though this view appears not in the text of the judgment itself but in the reasoning. [1] Chief Justice Kamekawa, for example, in the Fukuoka District Court case stated, “If the courts continue to avoid ruling on constitutionality, it is highly likely that the actions in question will be repeated. This Court has accordingly decided to take as its responsibility a consideration of the constitutionality of the shrine visits.” [2]

This applies precisely to the question of the constitutionality of the deployment of the Self-Defense Forces. Ever since the Supreme Court avoided a constitutional judgment in the Sunagawa Incident on the grounds of sovereign immunity, the Self-Defense Forces have expanded hugely, and now, they have been armed and sent overseas. [3] This is nothing other than the result of the judiciary’s avoiding its responsibility. Nevertheless, while relying on the doctrine of sovereign immunity, the Sunagawa decision also stated that if there is “blatant and egregious violation of the Constitution,” then the courts needed to pronounce on constitutionality. In the current case, in which heavily armed Self-Defense Forces have been sent to an overseas war zone, there is “blatant and egregious violation of the Constitution.” The State calls the deployment humanitarian support for reconstruction, but it is evident that in fact it is support for America’s invasion and occupation of Iraq. This is not only a constitutional violation, but it is also an illegal act violating the Self-Defense Forces Law and the Special Measures Law [Regarding Humanitarian Reconstruction Assistance Activities and Activities to Support Ensuring Safety]. Unless the deployment of the Self-Defense Forces is declared unconstitutional and illegal by a judgment from the judiciary at this time, there will be no brakes on Japan’s recklessness.

Fully three years have passed since the invasion of Iraq by the American and British armies. Security in Iraq has only deteriorated, and people’s lives are exposed to danger.

This demonstrates that peace cannot be created by force, that violence begets violence, and that the chain of violence only spreads. Therefore, in order to eradicate war, there is nothing to be done but to follow Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan “renouncing all war.” [4] Article 9 is truly a treasure in which Japan should take pride. People throughout the world are beginning to accord it respect.

The second judgment we ask the court to make is that the plaintiffs’ rights have been violated by the deployment of troops to Iraq, and that they have incurred serious damage.

The State simply denies us standing on the grounds that this is not a legal controversy, but as already mentioned in our preliminary statements, the only stipulation on this issue occurs in Article 3 of the Judiciary Law. [5] To interpret Article 3 narrowly and reject the Plaintiffs’ demand would violate the right to access to the courts guaranteed in Article 32 of the Constitution, and would constitute a failure to apply the law. [6]

The Plaintiffs claim that the following interests have been denied: (1) the right to live in peace, (2) personal rights, and (3) legally protected interests.

With respect to the right to live in peace, Professor Yamauchi Toshihiro emphasizes in his written testimony in Statement A-120 that the Preamble to the Constitution provides an explicit basis for such a right. [7] Please note his opinion that given how other countries recognize judicial norms in the preambles to their constitutions, there is no reason for Japan alone not to do the same. In the case at hand, we assert the right to live in peace based on the Preamble, Article 9, and Article 13. [8] In its response, the State willfully ignores Article 9 and separates the Preamble from Article 13 and denies their purport. This distorts the claims of the Plaintiffs and in no way constitutes a rebuttal.

As to personal rights: for the Plaintiffs, who have lived with the precept of “neither becoming a victim nor a perpetrator of war” as central to their character formation, these are rights that cannot be withdrawn.

In the last matter, that of legally protected interests under the State Redress Law, there are many precedents showing that even those rights not yet explicitly stipulated should be recognized. About the rights that the Plaintiffs charge have been violated, please, your Honors, listen to their voices. A decision to the effect that while the “anxiety” caused by leaflets in private mailboxes constitutes a legally protected interest, the intolerable mental anguish experienced by these Plaintiffs does not constitute the violation of a legally protected interest, would be a biased judgment, one surely to be censured by history. [9]

In conclusion, I would like to express my hope that you will not issue the sort of decision made in the case of the retrial of the Yokohama Incident, a decision that refused to address neither the torture committed by the former Special Police Forces nor the responsibility of the judges issuing the original guilty verdict. [10]

Given that one role of the court is to serve as a staunch guardian of the Constitution, we strongly hope for a judgment that takes even a single step beyond previous judgments in the direction of the Constitution.

The statement of attorney Owaki Masako

For twelve years, from Heisei 4 to 16 [1992-2004], I participated as a member of the House of Councilors in discussions of the Commission on the Constitution. I heard from people in various walks of life about their views on the country and the Constitution, and I also participated in work that analyzed each clause. Among the many opinions, the one that struck my heart was that Article 9 of the Constitution of Japan was a beacon of peace in the world, the object of interest and envy among the citizens of different countries, and that when Japanese citizens went abroad on peace missions with non-profit organizations, Article 9 served as the basis of the trust granted them as Japanese by the people of the world. The warm feeling the Plaintiffs hold towards Article 9 is a feeling shared by the people of the world who hope for peace.

Now, I will argue against the claim that the Plaintiffs have no standing as well as the claim that the right to live in peace is not a specific right.

The right to live in peace is a basic human right woven into the Preamble, Article 9, and Article 13 of the Constitution; it is none other than the right that embraces the freedom to pursue peace, to live in peace, and to negate war. It has specificity as the “right to live in a Japan that does not resort to war or force.” This is the brilliant theoretical achievement of constitutional jurisprudence in postwar Japan. The right to live in peace is a fundamental right in the twenty-first century.

The Japanese government violated both the Self-Defense Forces Law and the Special Measures Law Regarding Humanitarian Reconstruction Assistance Activities and Activities to Support Ensuring Safety when they sent heavily armed forces into what was clearly a war zone in Iraq, and it is clear that they are supporting the American and British occupation armies’ large-scale slaughter of Iraqi citizens.

It is evident that the invasion of Iraq was in violation of international law. Japanese lives are also being lost in Iraq. The fear and torment aroused in the Plaintiffs by the deployment of Self-Defense Forces to Iraq constitutes an infringement of each Plaintiff’s right to live in peace. This is nothing other than a direct and indirect violation of both their individual rights and legally protected interests. Our suit has not been filed for the sake of a merely abstract inquiry into the interpretation or value of laws.

Finally, I will say a word about the judiciary’s avoidance of pronouncing on discretionary actions by the legislative and administrative branches of government.

Democracy in the Diet is a democracy of majority rule, and there is no guarantee that it will to conform to law. If the opinion of the Court is that dispatching the Self-Defense Forces is a political decision to be left to the discretion of the government, then the Court has abrogated its own judicial role as a constitutional court. Please do not try to avoid judicial review.

The judiciary is the institution vested with the sole and therefore highest authority for the interpretation and application of the Constitution. In the case at hand, we hope that the conscience and wisdom of the Court and its awareness of its historic role will lead it to assume the role expected by the law and the people and rule that the right to live in peace has been violated.

Statements of the Plaintiffs

March 16, 2006

Tokyo District Court of Law, Civil Affairs Deliberation 15 System B

On living in postwar peace

Nagai Yoshiko (born 1935)

Your Honors!My name is Nagai Yoshiko.We fifteen Plaintiffs have filed this lawsuit from the conviction that the dispatch of Self-Defense Force troops to Iraq is a breach of the Constitution and that the only way to correct this wrongful action on the part of the government is to appeal to the judgment of the judiciary.When the U.S. government ignored international law and resorted to armed strikes despite the lack of both evidence and legitimacy, the Japanese government and the Koizumi administration, ignoring our precious Peace Constitution, decided on full-scale cooperation and sent troops overseas.For this they bear heavy responsibility.We fifteen differ in our life experiences, belong to different generations, and come from different social environments, but we have in common our hope for peace and our wish to act on our responsibility as citizens to preserve the peace and to pass on a peaceful Japan to the next generation. To that end we have made repeated efforts over the years.

Managing to escape the flames of air raids as an elementary school student and dodging machine-gun fire, I have been able to live in the peace of the postwar era.I am proud to have been taught by a national textbook in middle school that the Constitution of Japan has three great pillars, namely pacifism, popular sovereignty, and fundamental human rights.These are the thoughts that I have brought to this suit.I hope with all my heart that your Honors will show yourselves to be rightful guardians of the Constitution by finding the government’s action unconstitutional.

The hoped-for examination of each Plaintiff in the suit has been rejected, but on this day, all of the Plaintiffs would like to express their thoughts, in however limited a fashion. Because time is limited, we will speak one after another.

Memories of the Great Tokyo Air Raids 61 years ago overlap with Iraq

Ueda Tomoko (born 1925)

My name is Ueda Tomoko.Every time I see images in the news from the war in Iraq, the terror I felt during the Great Tokyo Air Raids of sixty-one years ago is revived.”Molotov Bread Baskets,” each one filled with dozens of incendiary bombs, rained down by the hundreds and the thousands. I was running about in confusion, trying to escape the flames, when, at the sound of the explosion of a one-ton bomb, my body froze.I cannot forget my friend who died, suffocated by the smoke.

Now, the same thing is happening in Iraq. Women and children are shot, innocent citizens are burned and robbed of life. The Iraq War is fresh salt rubbed in my old wounds from sixty-one years ago.

I cannot bear the anguish of knowing that Japan, with its Peace Constitution, is involved in this war.

We have been apologizing to the peoples of Asia

and seeking reconciliation and peaceful coexistence

Shimizu Sumiko(born 1928)

My name is Shimizu Sumiko.The Manchurian Incident, the Sino-Japanese War, and the Second World War filled my first seventeen years.Loyalty to the emperor and the state and militarism were drummed into me.My days were spent participating in lantern parades to celebrate military victories, making care packages for soldiers who were overseas, seeing soldiers off, making thousand-stitch belts, and volunteer labor.The use of the enemy’s language, English, was prohibited.There were daily air raid drills, practice sessions with bamboo spears on scarecrows, helping out with the farm work—even making charcoal—at the homes of soldiers gone to the front, and getting sent off as volunteer corps to work in munitions factories.In school, there were no classes, and not being able to study was the hardest part.

I experienced the 1945 great air raid of Osaka and the air raid of Fukui.People running in confusion, trying to escape the hail of incendiary bombs wrapping the city in fire; American soldiers in low-altitude airplanes firing at them with machine guns; fallen bodies piling up; mothers fleeing with bloody babies on their backs; burnt and festering corpses lying in the streets; and me, also fleeing, covered in water-soaked bedding.Everything about that time overlaps with the experience of the Iraqi people now.Whenever I think of the Iraqi women and children who are exposed to incomparably greater destructive forces, I cannot bear the pain.

I held a seat in the Diet for twelve years. During that time, we sincerely reflected upon and apologized for the infringement of human rights and the virtual enslavement of colonial populations that took place under Japan’s colonial rule and war of aggression. We have made efforts toward reconciliation and peaceful coexistence with the peoples of Asia, and we have repeatedly said to them that Article 9 in the Constitution stands as proof of our pledge never to let these things be repeated. We must immediately stop the dispatch of troops to Iraq, which violates the Self-Defense Forces Law and the Constitution.

The shock of learning that nothing was told to us during the war

Nozaki Mitsue (born 1932)

My name is Nozaki Mitsue.What scares me more than anything is the fact that a nation that wages war will come to rule over the hearts and minds of its citizens.I didn’t even know that during the war, places around Japan other than Tokyo had been subjected to air raids.No matter how bad the war situation, the news shouted, “Glorious results on the battlefield” with “Our losses are slight” tacked on at the end.Even with the extreme exhaustion caused by the nightly air raids, no one could say, “I can’t take any more!”We couldn’t challenge the government’s assertion that victory was assured because Japan was a country of the gods, ruled by an emperor from an unbroken imperial line.Jeered at as unpatriotic or traitors, monitored by the authorities, the armed forces, society, schools, and neighborhood organizations, we were roped into useless drills with bamboo spears or long-handled swords.Children during wartime knew nothing of the real state of things and were made to believe whole-heartedly that we would win.It was forbidden, like a crime, to have thoughts of one’s own.

Now, I feel the mindset of that time is being revived. When the “Law to Protect the People in Conditions of Armed Attack” [passed 2006—Tr.] was being debated, I recalled the mandated destruction of buildings during the war. This was allegedly to make a buffer zone to control the spread of fires. In Hiroshima, under the scorching sun, with no protective gear, middle school students dashing off to perform that task suffered the direct hit of the atomic bomb. They were thirteen years old, the same age as me. I didn’t know this until long after the end of the war. When I think about what I was doing at the time, my heart aches. The shock of not having known, the shock of not having been informed—this was the case with Okinawa, the Nanking Massacre, Unit 731, and the comfort women—I learned about these things much, much later. War is also about this kind of restriction on people’s psyches and on what they know.

To realize a democratic society, our unflagging efforts are necessary

Kase Satsuki (born 1935)

My name is Kase Satsuki. When I was in my first year of middle school, I came across a textbook called The Story of the New Constitution.The textbook spoke to us, like this:”Now, the war has finally ended.Don’t you agree that you never want to experience such terrible sad feelings again? ….To engage in war is to destroy human beings.It means wrecking the good things in the world.” How refreshing it was!The textbook went on to say, “Two decisions were made in our new Constitution to make sure the country of Japan would never wage war again.”Even now I can vividly recall what the textbook said about the renunciation of war capabilities and the exercise of military force, and how forcefully it stated, “Japan has done the right thing, ahead of other countries.”

In 1952, when I was seventeen, there was a special election for the upper house in ShizuokaPrefecture where I lived, and I became involved in the investigation of systematic election fraud, which I considered the “destruction of the fundamentals of democracy.” Thanks to this, I was ostracized.Having gone through that experience, I felt keenly that in order to realize the peaceful and democratic society promoted by the Constitution, we the sovereign people had to make unflagging efforts.Thereafter, having taken part in long campaigns in a variety of postwar citizens’ movements and peace movements over the course of half a century, I feel ever more deeply that the principle of the Peace Constitution, which aims for “the realization of peace without depending on military power,” is a compass not only for realizing peace in Japan but throughout the world, and that our Constitution is a treasure we should boast of to the world.The past several years, however, with the passage of three emergency laws, the Special Anti-Terrorism Law and other war-related laws, and the strong-arm tactics used to dispatch troops to Iraq, I cannot help feeling an impending crisis in which the Constitution will be annihilated.Through the practice of such unconstitutional politics, Japan is being distorted into “a country that is able to go to war” once again and this, I believe, must not be permitted.

Through involvement with the Japanese military “comfort women”

Ueda Sakiko (born 1939)

My name is Ueda Sakiko.In the Asian Pacific War, Japan not only killed an estimated twenty million innocent people, but it also engaged in outrageous antihuman practicessuch as forced labor, military sexual slavery in the form of “comfort women,” the Nanking Massacre, and medical experimentation on living bodies.In particular, I cannot stop thinking about those women who, at the height of their youth, were forced to become sex slaves as the Japanese military’s “comfort women,” who were robbed of their lives by that experience.Most of these women were forcibly taken from Japanese colonies or occupied territories, or tricked and taken away, to be trampled upon as the object of soldiers’ sexual violence every day.Even after the war ended, there was no restoring anything like a normal human life for these women.Finally, in the 1990s, a group of courageous victims denounced the comfort women system and sued the Japanese government, but all their actions have been dismissed.The United Nations’ Commission on Human Rights, Sub-commission on the Prevention of Discrimination against Women, has demanded a fundamental settlement from the Japanese government, but the Japanese government has made no effort even to respond to the victims’ demands for justice.

In Iraq there have already been over one hundred thousand deaths in the prevailing state of war.In addition, the terrible torture in Abu Ghraib Prison and other human rights violations are coming to light together with a rapid increase in sexual violence against women.As a woman, I find these things unbearable.It is out of the question for the Japanese government to be collaborating in consigning women to such a situation.Japan must immediately cooperate in the restitution of the human rights of women.

In the burdens of my father and my uncle,

the origins of the movement to advocate human rights

Tsuwa Keiko (born 1945)

My name is Tsuwa Keiko. My father was an officer in the Kwantung Army. He moved from place to place in battles throughout Asia, and even though he returned immediately after the end of the war, a military tribunal found him guilty of POW abuse. The Chinese my father taught me was the words, “Guniang lai lai” (“Miss, come here”).The tone in which he said this was unpleasant to my child’s ear, but as I grew up and found out about the atrocities of the Japanese military throughout Asia, it became a source of anguish for me.I did not hear anything about that period from my uncle, a military policeman, but in later years, my father sought redemption in religion.

Today, sixty-one years after the end of the war, the Japanese government has forgotten the acts committed by Japan in the past.It is not only legitimizing war and accepting the prime minister’s worship at Yasukuni Shrine, but it is going so far as to introduce explicit plans to revise the Constitution in an attempt to make it so that Japan can once again invade other countries.I absolutely cannot forgive this trend toward policies leading to the quagmire of war, abetting America’s unjustified attack on Iraq with an army called defense forces.Just thinking of what the Self-Defense Forces, now turned into an army, will do on the battlefield of Iraq makes my heart ache.Who can state positively that they will not conduct themselves in the same way as the Japanese army of the past?Who can promise that women, the elderly, and children will not become casualties on the battlefield?

In solidarity with the women who suffer under the value system of male dominance

Kobayashi Michiko (born 1947)

My name is Kobayashi Michiko.I work in a law office.In most cases where women come to consult about divorce, there is a violent husband.A woman from Hokkaido, tossed out of doors in arctic temperatures while pregnant; a person who had been kicked and had her bones broken; women who had been coerced into sexual intercourse: these women are all deeply scarred not only on their bodies, but in their hearts.Violence not only destroys women’s self-esteem, but the fear and despair drive the women into self-abnegation and cause them to lose the will to live.

The male chauvinist thinking and values displayed here are similar to what happens in war.Citizens are choked by gag orders, thought-control is put into effect, and violence is glorified: this is the system of war.The images from the reports on the miserable state of affairs in Iraq overlap with the image of women suffering from domestic violence, and this tears at my heart.Scarred by these images, I have begun to suffer from daily nightmares. I am currently on medication. Nothing can cure me other than the smiling faces of the Iraqi people.There is no cure other than images of an Iraq in which life is not threatened, in which everyday life has been restored. Among the American soldiers who participated in the war, I hear that the number of those who suffer from exposure to depleted uranium shells and those suffering from stress is increasing.It has also been reported that three Self-Defense Force members returned from Iraq have committed suicide, and there are many who are suffering from trauma.

The lives of all people, from every country, are equally precious.Surely, it is the role of the Japanese government to spread the spirit of Article 9 of the Constitution.

Let’s change the way we fight terrorism under the Peace Constitution

Niwa Masayo (born 1947)

My name is Niwa Masayo. I was born in 1947. I am proud of being the same age as the Constitution and the Fundamental Law of Education. Accordingly, in the days when I was a teacher, I thought about how I wanted to clearly convey this pride to the children. I used to say to them, “Just because we don’t have an army doesn’t mean that we have to be afraid. Through our decision to renounce war, we have chosen the path of walking together with the peoples of the world.”

I am deeply hurt by the fact that the Japanese government is actively involved in the attack on Iraq and in the inhumane occupation of that country.

In particular, after the incident in London last July, I have begun to feel that the fear that I myself, my family, or my friends could also become the object of an armed attack has become more realistic.

I want to change the way we fight terrorism.The Japanese Constitution, which proudly repudiates war, is at once the greatest and most reliable foundation for responding to terrorism.Already, many Iraqis have been victimized, and the number of dead and wounded American soldiers is also increasing.Japanese have also died.The government must withdraw from the war as soon as possible and move towards the realization of peace.

The fear of terror from working in a British company

Yuzuki Yasuko (born 1948)

My name is Yuzuki Yasuko.I don’t know war firsthand, but I heard repeatedly about the sufferings caused by war and the preciousness of peace from my grandmother, who experienced the Sino-Japanese War, the Russo-Japanese War, and the Second World War; from my mother, who lost her son and husband in the war; and from my older sister, who experienced compulsory school evacuation and evacuation to live with distant relatives.My mother, who turned 85 this year, often says that when she heard the emperor’s surrender broadcast, she thought, “It’s good we lost the war.Now we’ll have more rations.The military will no longer treat us like worms.”

I work for a U.K.-owned company.Ever since the Self-Defense Forces were dispatched to Iraq, the company doors have been kept locked. This is not only because it is a corporation based in Britian, which joined the U.S. war of aggression against Iraq, but because Japan has also become a target for terrorism.In addition, the entire staff was sent e-mails pointing to the “danger of riding the subways,” and we were told to be “careful about going home during the commuter rush hour.”This is a danger that has arisen since the Self-Defense Forces were dispatched to Iraq.It is also said that after London, Japan is at risk.We will have to live every day in fear until the withdrawal of the Self-Defense Forces.

When I travel in Asia, I meet people concerned with remembering the brutal acts of the Japanese armed forces here and there, but even given that history, I realize I was accepted because Japan has a Peace Constitution.Over the past few years with Prime Minister Koizumi repeating his visits to Yasukuni Shrine, I have sensed the feeling towards Japanese people becoming worse in China, which I visit every year.I am afraid Japan will choose a path that will cut it off from the rest of Asia.

As a second-generation atomic bomb victim,

I think the use of depleted uranium shells is unforgivable

Mishima Hiroko (born 1949)

My name is Mishima Hiroko.I am a second-generation atomic bomb victim.My mother, who at age twenty was enrolled in a Higher Girls’ School Specialist Course,was an atomic bomb victim in Nagasaki.Even though she herself was hurt, she went out to help numerous regular-course students who had been bombed in the Mitsubishi Armament works.

When she wanted to go back to rescue more people, she couldn’t move, and after several days, she thought, “If I’m going to die anyway, let it be at home,” so she went home.For many years, she was tormented by the thought that in leaving Nagasaki, she had not properly mourned the dead or rescued her juniors.When my mother was a teacher, she continued to express these thoughts, and I feel my own life came as an extension of those feelings.Each time I myself gave birth, I thought, “What if the effects of the Flash show up in this baby….”It is precisely for this reason that I want to pass on to my children a peaceful society and to work to prevent the repetition of such tragedies.

Thinking of the effects of residual radioactivity, I believe it is because my mother left Nagasaki that I am here today. That is why I cannot forgive America for using depleted uranium shells. Since residual radioactivity from the dust caused by depleted uranium shells can reach 1,000 kilometers in every direction, the people of Iraq could be driven to extinction. Due to the same depleted uranium shells of the Gulf War, deaths have also occurred among the American soldiers who participated in the attack, and disabled children have been born as well. The effect on children is serious. If we are going to talk about providing reconstruction aid, we should concentrate our energy on research to remove radiation. That would be humanitarian support.

I want to stop Japan from turning into a garrison state

Sugita Yoshiko (born 1951)

My name is Sugita Yoshiko.It is clear that the Iraq War is unjustified.The dispatch of Self-Defense Force troops to Iraq is also clearly in violation of the Constitution.The use of napalm bombs, chemical gas, nerve gas, anaesthetic gas, and other poison gases is turning Iraq into a testing ground for illegal weapons.It is said that the internal organs of Iraqis have been extracted and dispatched to America, so the nation acting inhumanely is in fact America itself.Due to an effort to control information, Al-Jazeera, that invaluable resource, has been blocked.If we can only receive one-sided information from the U.S. military, the truth is likely to be concealed.

While the armies of other countries are being withdrawn, Prime Minister Koizumi has decided to extend the deployment of the Self-Defense Forces in Iraq.What a reckless, foolish act.The silent media, a prime minister servile towards the United States, the profit-seeking arms traders, the hypnotized citizens:I want to stop Japan from turning into a garrison state.Learning from the Costa Rican Supreme Court Constitutional Chamber that forced the cancellation ofsupport for the United States, may this Court deliver a constitutional judgment showing the discernment of the Japanese judiciary.

The dispatch of troops coincides with the militarization of the schools

Ishida Kuniko (born 1951)

My name is Ishida Kuniko. I myself have no experience of war, but through living with two children who are seventeen and nineteen, I feel keenly the gravity of a person’s life. Therefore, I am intensely angered by the distorted citation of the Preamble to the Constitution that Prime Minister Koizumi presented in justification of sending the Self-Defense Forces to Iraq. Such invocation destroys the spirit of pacifism and of internationalism; it is an insult to the Peace Constitution I take pride in.

From about the time the Japanese government began preparing to dispatch the Self-Defense Forces to Iraq, in classrooms we witnessed a cessation of respect for a diversity of perspectives and saw the dominance of a culture that attempts to control even the hearts of children through enforced salutes to the Rising Sun flag and singing of the Kimi ga yo [the national anthem—Tr.].Sex education, which promoted individual autonomy, the establishment of the human rights of women, and respect for the human rights of others, has been subjected to intense attacks.The state and local governments, by imposing particular values, are turning schools into places that teach obedience and the submersion of individuality.

As a citizen of Japan, which is taking part in a war that tortures the people of Iraq, I am deeply sorry and feel tormented by emotional pain.At the same time, my family and I cannot get over the fear that we ourselves might be subjected to a terrorist attack.As a mother and as a member of the citizenry who have general responsibility for the education of children, I am deeply troubled by the militarization of the schools.

Having experienced the terror of 9/11, I plead together with the life granted then

Nakano Keiko (born 1969)

My name is Nakano Keiko.I was in New York where my husband had been sent on business, and so I experienced the 9/11 terror attacks.

Fortunately, since we were far from our apartment at the time of the attacks, we were not directly affected, but our apartment was close to the World Trade Center. It was two weeks later that we were able to enter our apartment. Even though we had managed to get through the rigorous security check, I did not have any proof of residence on me, so I was accompanied into my apartment by a distraught soldier. Treated like a criminal, I wailed in bitterness and sorrow. Ashes containing asbestos had gathered by the windows.

After 9/11, I think all New Yorkers were in a state of PTSD. A group of 9/11 victims’ families (Peaceful Tomorrows) demanded that no war be waged in the victims’ names, but Bush kept saying, “We will not give in to terrorists.”

The daughter conceived in the place where 2,700 people lost their lives is now three years old. Hers is a life conceived in an apartment permeated with foul odors, where I shut myself in, feeling guilt at being alive as well as gratitude for our good fortune, and struggling to understand how I should go on living. For my daughter’s sake, too, I must create a peaceful world where people need not live in fear of war and terrorism. I beg the Court to hand down a courageous decision such that Japan will not be a target of terrorism, that the blood of the citizens of the world need not be spilled.

I cannot appear in court today due to the imminent birth of my second child. But even though I am not in the courtroom, I am giving my full attention to the outcome of this trial. For the sake of my daughter and the child that will soon arrive, as well as for the sake of all the world’s children, I place my hopes for peace in your Honors’ courage.

The thoughts of one who has continued in the grassroots peace movement

Ishizaki Atsuko (born 1924)

My name is Ishizaki Atsuko. My youth was passed in wartime. When I was in grammar school, we prepared care packages for soldiers on the front and took part in lantern parades to celebrate the fall of Nanking. High-spirited with visions of victory, we knew nothing about the Nanking Massacre or the military comfort women. We were ecstatic to hear the results of the attack on Pearl Harbor from Imperial Headquarters. After that, air raids became frequent, daily provisions became scarce, and we had to start mixing our meager rations of rice with wild grass to make porridge to stave off hunger.

I became a teacher at a girls’ school where I had been evacuated, but instead of teaching, my role was to accompany students who had been mobilized to help with farm work or to work in factories in Yokosuka. When we were exhausted by air raids day and night and utterly drained of vitality, the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the war that had claimed over twenty million lives ended. But we had in our grasp the unexpected treasure of the Peace Constitution.

We had thought there would be no more war, but the next thing we knew, there was the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty, the Self-Defense Forces, and then the deployment of troops to Iraq. Since the 1960 struggle over the security treaty when I felt compelled to take my five-year-old daughter to demonstrate at the Diet, I have continued my anti-war activities. Now I am past the age of eighty, but I intend to continue speaking out against war for the rest of my life.

I have something to say to the prime minister who insists that dispatching forces to Iraq is a service to the world community as called for by the Constitution, and to the young folks watching television who think that war is cool. War is an activity in which people rob each other of life. Not just soldiers sent to battle, but young children and the elderly also get caught up in war, and the chain of violence has no benefit. We who have experienced the horrors of war do not want our children and grandchildren to go through the same thing. We should stop violating our Constitution by being servile to America in its reckless war in Iraq. Instead, we should withdraw immediately and make a contribution to international peace that does not involve dispatching the Self-Defense Forces. This is the judgment I ask your Honors to make.

I want a society that actualizes Japan’s Constitution,

gained as a result of war

Ueda Tomoko (born in 1925)

My name is Ueda Tomoko. I would like to say one final word. I was born in Taisho 14, the year 1925. My adolescence and youth coincided with the war. Can this court imagine what it is like to live with hunger and fear for your life, to feel that a single utterance could put you at risk? Now the politicians and elites of this country who do not know war are lightly discussing matters that will lead to war. A life once lost cannot be regained.

The Japanese people have a duty to all who sacrificed their lives in the war to uphold the vision and lofty ideals of the Constitution of Japan, which we gained as a result of defeat. In order to pass on to the next generation a society that will actualize this Constitution, I want to bequeath these words to the generations that do not know war. I want them to be aware of the importance of peace and to continue our efforts to preserve it. I want them to know that it will be too late once that peace has been lost. I want to entrust these words to the judiciary, the guardians of the Constitution, as the last testament of Ueda Tomoko.

Final Preliminary Brief

March 16, 2006

Tokyo District Court of Law, Civil Affairs Deliberation 15 System B

Nakajima Michiko, Attorney et al. (7 other individuals)

Table of Contents

Introduction

Section 1 Regarding Defendant Exhibit No. 7 (Kofu District Court Judgment)

1. Grounds for citing Kofu District Court judgment

2. “Findings of fact” for Kofu judgment

3. Rejection of right to live in peace

4. Rejection of personal rights and personal interests

5. Rejection of claims for compensation

6. Significance of Kofu District Court judgment

Section 2 Issue for judgment 1

Constitutionality and legality of dispatching troops to Iraq

1. Significance of the power of judicial review

2. Comparison with lawsuits contesting constitutionality of Yasukuni Shrine visits

3. Necessity for judicial review

4. Representative democracy and judicial review

5. Duty to uphold constitutionalism

6. Troop deployment in Iraq—unambiguous constitutional violation

7. Dispatching of SDF to Iraq also violates Special Measures Law for Iraq

8. State of affairs in Iraq and SDF activities

9. Withdrawal of Ground SDF and shift to new government

10. Iraq and significance of the Japanese Constitution

Section 3 Issue for judgment 2

Plaintiff interests violated by dispatching troops to Iraq

1. Standing and jurisdiction (Article 23, Constitution)

2. Right to live in peace

3. Personal rights

4. Legally protected interests

Section 4 Claims for relief

1. War responsibility of judges

2. The courts as guardians of the law

Introduction

Your Honors, do you not hear the footsteps of war? To the Plaintiffs, the sound is loud and clear. War is getting ever closer. Any day now, it threatens to take over our everyday lives and wreak its horrors on our youth and unborn children. We sense the approaching danger. Keenly feeling the need to halt this relentless tide, the Plaintiffs have brought this case before the court. Time and again, we have submitted briefs and detailed the charges. But, despite these efforts, the Defendant, the Government of Japan, has not deigned to contest the charges, much less answer them in court. They have only submitted judgments delivered in other cases as exhibits supporting their position and have remained virtually silent in court.

Under these circumstances, the Court rejected the request to examine the Plaintiffs’ witnesses and the Plaintiffs themselves. Given that the Plaintiffs have submitted abundant documentary evidence, this is truly deplorable. We sincerely hope that this esteemed Court will carefully examine the evidence and hand down a ruling that will allow it to fulfill the historic role expected of it.

Section 1 Regarding Defendant Exhibit No. 7 (Kofu District Court Judgment)

1. Grounds for citing Kofu District Court Judgment

The Defendant State has submitted Defendant Exhibit No. 1 and Defendant Exhibit No. 7 as pertaining to this case. While these exhibits consist of court rulings or decisions, they differ in many respects from this case in that they are decisions on the Special Measures for Terrorism Law and administrative litigation, and moreover, the reasons for the claims made in many of these cases are different. Of these two exhibits, Defendant Exhibit No. 7 consisting of the Kofu District Court judgment is similar to this particular case, and the Defendant has also requested that the court refer to it in its Explanation of Filed Exhibits (4). As such, the following statements proceed with arguments against the judgment in the Kofu District Court as a way of contesting the Defendant’s claims in this case.

2. “Findings of fact” for the judgment

The judgment by the Kofu District Court is premised on the following findings of fact (facts evident to the Court): The Self-Defense Forces (SDF) have successively dispatched units to Iraq since December 18, 2003. Troops are authorized to carry out activities that primarily consist of restoring and supplying medical, water, and public facilities and transporting related goods, etc. (humanitarian and reconstruction support) and supporting other nations in their activities to restore security and stability in Iraq.

The Defendant, however, has made no attempt whatsoever to verify whether the SDF is engaged in the above activities. The Plaintiffs, have, on the contrary, established that the SDF is not engaged in these activities. As proof, we have submitted the following exhibits, which establish the fact that the SDF is engaged in neither water supply nor in public facility reconstruction, etc.: Plaintiff Exhibit No. 105 (“Humanitarian Water Support—Japan Gets Lapped,” Tokyo Shimbun [11]); Plaintiff Exhibit 107 (“Justification for Deployment Getting Fuzzy,” Tokyo Shimbun); Plaintiff Exhibit No. 108 (“Increased Security for Ground Forces,” Asahi Shimbun); Plaintiff Exhibit No. 109, 1, 2 (statement of questions by Representative Kazuo Inoue, House of Representatives, and government response); Plaintiff Exhibit No. 110, 1, 2 (statement of questions by Representative Tomoko Abe, House of Representatives, and government response); and Plaintiff Exhibit No. 76 (Watai Takeharu’s documentary film Little Birds [Ritoru baazu]). In addition, the Plaintiffs have submitted Plaintiff Exhibit No. 77, 1, 2 (Watai Takeharu’s documentary film Destroyed Friendship [Hakai shita yuko]; Takato Nahoko’s What’s Really Happening in Iraq Now [Iraku de ima hontoni okotte iru koto]), etc. These exhibits establish that SDF deployment in Iraq has changed Iraqi sentiment toward the Japanese—from amity to enmity—and that it is contributing to a decline in public order and safety.

In making its judgment, the Kofu District Court, without examining the evidence presented, simply asserted that SDF engagement in the activities for which they had been dispatched constituted “facts evident to the Court.” The ruling is appalling in its negligence of the most basic rule of fact-finding, that is, examination of evidence.

3. Rejection of Right to Live in Peace

(A) The Kofu District Court Judgment rejects the Plaintiffs’ right to live in peace, the right to pursue peace, and the right to live in a Japan that does not exercise the use of force or engage in war.The arguments put forth by the Plaintiffs in the Kofu District Court are not necessarily the same as those of the Plaintiffs in this case, but the DefendantState offers similar substantiation for its position in both cases.For this reason, we cite the Kofu District Court’s Judgment below as a means of rebutting these points.

The Judgment cites the following in its rejection of the right to live in peace:

(1) The concept of peace is necessarily open to divergent interpretations depending on a person’s philosophy, beliefs, worldview, and values.Based on different ways of thinking, the specific means and methods to realize peace also vary.

(2) This is evident from the fact that the Plaintiffs are strongly opposed to the Special Measures Law passed by the Diet, which is entrusted by the people to act on their behalf. According to this legislation, its aim is “to contribute to the peace and security of international society, including Japan.”

(3) The Plaintiffs assert that the Constitution unequivocally employs the term “demilitarized peace” as the means by which to realize peace, but the concept of “demilitarized peace” is also unavoidably open to divergent interpretation.

(4) As a result, when we refer to the present Constitution, whether the Preamble or Article 9, it is not possible to know immediately what concept of peace and what means and methods of attaining peace are legitimate, or which ones superior.

(B) Objections to the above reasons

It can only be said that the reasons given above by the Kofu District Court in its ruling are utterly appalling in their disregard for the Constitution. In past so-called “peace lawsuits,” some lower courts have rejected the people’s right to live in peace, but none have disregarded the Constitution to this extent or treated it with such contempt.

The reason cited in (1) above might be plausible if the Preamble and Article 9 of the Constitution were regarded as nonexistent and the issue were limited to a consideration of individual views, beliefs, etc.; but if we take the current Constitution as our premise, it is not possible to assert that there are diverse means and methods of concretely realizing peace and that various ideas can be put into practice. Regardless of how diverse individual views and beliefs may be, when the Constitution sets forth only one ideal and the means or method by which to achieve it, it is incumbent upon the state (including the judiciary) to abide by it.A ruling that refuses to do so, such as the above-mentioned Judgment, is one that fails to uphold the Constitution.

The reasons cited in (2) are grossly mistaken and logically flawed. First, it is claimed that the Special Measures Law for Iraq was passed by the Diet, which is entrusted by the people to act on their behalf, with the aim of contributing to the peace and security of the international society, including Japan, but the people of Japan have not entrusted the Diet to pass this special measures legislation for Iraq. In the upcoming elections, the special measures legislation for Iraq has not been put before the people for debate, and public opinion polls invariably show that a majority of the people opposed to the deployment of SDF troops to Iraq (Defendant Exhibit No. 106).

Second, the Plaintiffs are strongly opposed to the Special Measures Law for Iraq because it is a violation of the Constitution, not because of their individual worldviews or values.To reduce the assertion of Constitutional violation to a question of worldview, and to then switch the argument to one about the basis for “diversity” betrays an illogic so disgraceful that one is tempted to avert one’s eyes .

The reason cited in (3) above is based on the claim that the notion of “demilitarized peace” is unavoidably open to divergent interpretation, but Article 9, Paragraphs 1 and 2, unequivocally asserts a “demilitarized peace” in stating that “land, sea, and air forces, as well as other war potential, will never be maintained. The right of belligerency of the state will not be recognized.” This law was confirmed and enacted by a constitutional assembly and clearly explained to the people in Plaintiff Exhibit No. 1, The Story of the New Constitution [Atarashii kenpo no hanashi] and other materials. Subject to the government’s agenda, the interpretation of Article 9 has since changed, but the constitutional provisions themselves have not been revised and do not admit of ambiguous or equivocal interpretations. Thus, although political positions may effect changes in interpretation, it is not to be expected that judges, who are bound by duty to honor the Constitution, simply follow suit.

4 Rejection of personal rights and personal interests

(A) Grounds given in Kofu District Court Judgment

The Kofu District Court judgment rejects the allegation that the plaintiffs’ personal rights and personal interests have been violated on the following grounds:

(1) The troop deployment does not directly require Plaintiffs to carry out a duty or achieve a result; nor is there the risk or fear of endangering the Plaintiffs’ lives or violating their persons. Even assertions of the rising risk of terrorist attacks based on the diverse motives and causes behind terrorist acts cannot be verified in terms of concrete and realistic risk.

(2) It can be surmised that the Plaintiffs harbor strong aversion to the troop deployment and that this could plausibly be construed as mental anguish. This sentiment, however, should be situated in the realm of emotion—of feelings of righteous indignation, displeasure, irritation, disappointment, etc.—arising from opposition to measures and policies decided and implemented by the state under a system of representative democracy that conflict with individually held beliefs, convictions, and interpretations of the Constitution, etc. This sort of mental anguish is inevitable when decisions are made according to the principle of majority rule, and should either be redressed through activities directed at criticizing state policy and seeking wider acceptance of the legitimacy of one’s own understanding of the issue, or endured as a necessary aspect of life under representative democracy. As such, however severe the mental anguish may be in subjective terms, the private emotions of individuals cannot be deemed as meriting protection under the law and cannot be construed as infringing on personal rights or exceeding the limits of forbearance that are generally expected by society at large.

(B) Objections to grounds given above

According to the reason cited in (1) above, the diversity of motives and causes of terrorist attacks makes it impossible to verify with certainty whether the concrete and realistic risk of terrorist attacks has increased. It is difficult to contain one’s amazement at such a statement. The Plaintiffs are not asserting that there is a general risk of terrorism, but rather that armed groups have protested the assistance given by Japan’s SDF to the U.S. invasion of Iraq and have named Japan as a target for reprisal (Plaintiff Exhibit No. 104), and that in actuality, indiscriminate terrorist attacks have occurred in Spain and Britain, nations that have deployed troops in Iraq. Are the judges who refuse to recognize this danger suggesting that they are in a position to guarantee the safety of Japanese nationals?

This judgment, which denies the rising risk of indiscriminate terrorism, completely rejects the Plaintiffs’ claim that the troop deployment to Iraq has generated feelings of anxiety and fear that their lives and personal safety are endangered.

The fear of terrorism is a constant subject of discussion in the United States, and many share feelings of anxiety. In Japan, a nation which is supporting the United States, there is undeniably good reason to fear terrorism and feel anxious

As seen in the reason cited in (2), a significant part of the judgment calls for forbearance regarding all acts of the Diet and the government in the name of representative democracy. It is precisely because we have a representative democracy that the judiciary is given the authority to determine questions of constitutionality, and this point will be addressed below. As stated above, however, the people of Japan have not mandated the Diet to pass the Special Measures Law for Iraq or to dispatch the SDF to Iraq, and these actions are opposed by a majority of the people. This indicates that representative democracy in Japan is becoming defunct, and judges who nevertheless declare that we should endure decisions of the Diet because they are based on the will of the majority have repudiated the very principles of democracy.

5. Rejection of claims for compensation

The Kofu District Court Judgment, in rejecting the Plaintiffs’ demand for compensation, acknowledges that under the State Redress Law, Article 1, Paragraph 1, illegal acts committed by the state for which compensation may be demanded, consist of violations not only against established rights, but also against those that are not yet clearly established as legally protected rights in cases where their violation may be deemed illegal; and that when the mental anguish of an individual exceeds the limits of endurance that are generally expected by society at large, there are times when personal rights should be legally protected, and that depending on the manner and degree of infringement, there is room for acknowledging that an illegal act has taken place. Nevertheless, it states that because the right to live in peace and pursue peace can be considered neither a concrete right nor interest, it is not possible for these rights to be violated, and for this reason rejects the Plaintiffs’ demands.

It is, however, manifestly contradictory to state in the first half of a judgment that even when some rights are not yet established as concrete rights, the mental anguish of an individual may sometimes require legal protection, and then to state in the second half that because the right to live in peace and the right to pursue peace are not concrete rights or interests, the demand for compensation is groundless. The judgment also rejects the demand for compensation because it is impossible to imagine a situation in which the Plaintiffs’ personal rights and personal interests have been infringed by the dispatching of the SDF to Iraq. The judgment makes no mention, however, why it would be not be possible to imagine such a situation. The lapse in reasoning is blatant.

6. Significance of the Kofu District Court Judgment

As stated above, the judgment of the Kofu District Court is tantamount to the judges abandoning their responsibility to the law and announcing the suicide of the judiciary. We only hope that such a judgment will not be delivered in this case.

Section 2 Issue for judgment—the constitutionality and legality of dispatching troops to Iraq

1. Significance of judicial review

Under the separation of powers set forth in the Constitution, the judiciary exercises its authority independently of the legislative and administrative branches. Article 76, Paragraph 3 states, “All judges shall be independent in the exercise of their conscience and shall be bound only by this Constitution and the laws.” According to Article 99, judges have the obligation to respect and uphold the Constitution. Furthermore, Article 81 gives the courts the power of judicial review, and under the separation of powers, the judiciary has been established to determine whether laws or dispositions are in conformity with the Constitution. As stated above, in representative democracies, laws and ordinances as well as government actions will often conflict with the will of the people, and for this reason, the judiciary’s exercise of judicial review is a necessary and essential practice for ensuring order consistent with the Constitution.