Burden Sharing, Security and Equity in the Straits of Malacca

By Nazery Khalid

In 2005, more than 62,000 ships sailed through the Straits of Malacca, one of the world’s busiest and most important shipping lanes. Linking East and Southeast Asia with the world, one third of world trade and half of global oil pass through the Straits.

The Straits of Malacca

With projected growth in global trade and the rise of East Asian economies, financial demands can be expected to grow on the littoral states—namely Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore—to ensure navigation safety and control marine pollution. In addition, the heightened perception of risk to ships traversing the Straits due to threats of piracy and terrorism has led to increased security costs.

Considering that an estimated 80% of vessels traversing the Straits are on transit, the littoral states have called for burden sharing in various meetings and conferences over the years. However, there has been little follow-up by the stakeholders to collectively address the issue, and still less effort to come up with an acceptable and workable operating mechanism. Drawing on presentations at the recent International Maritime Organization Meeting (IMO) in Kuala Lumpur, this article presents a case for burden sharing in the Straits.

The Cost of Maintaining the Straits to the Littoral States

The issue of burden sharing between the littoral states and international users of the Straits to enhance security in the waterway took center stage at the Kuala Lumpur Meeting on the Straits of Malacca and Singapore (KL Meeting) organized by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) on 18–20 September 2006. The meeting, themed ‘Enhancing Safety, Security and Environmental Protection’, addressed existing and evolving mechanisms of cooperation, and explored modalities for future collaboration among the stakeholders.

All ships enjoy the right to use the Straits of Malacca, as provided for in Article 38 in Part III of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982, pertaining to transit passage through straits used for international navigation. Although this guarantees the right of international users to traverse the Straits, the burden of maintaining and securing the waterway has always been shouldered by the littoral states. Thus far international users have not matched their extensive usage of the Straits with proportionate contribution to the costs of maintaining and securing it.

Cargo ship in the Straits

In addition to Article 38 of UNCLOS, Article 43 of the Convention on navigational and safety aids and other improvements and the prevention, reduction and control of pollution states that user states and states bordering a strait should by agreement cooperate:

in the establishment and maintenance in a Strait of necessary navigational and safety aids or other improvements in aid of international navigation; and for the prevention, reduction and control of pollution from ships.

In line with Article 43, the Straits’ stakeholders have allocated resources and sought to preserve environmental integrity. The waterway is rich with marine resources which provide livelihood to many people in the littoral states. As such, it is paramount to protect the harvest and maintain its environmental integrity to ensure that economic activities such as fishery and marine tourism and recreation can continue to develop in a sustainable manner. Such important socio-economic pursuits depend largely on the viability and pristine condition of the Straits ecosystem and environmental condition.

The Straits is a navigationally challenging waterway due to its geographical features, including narrow channels, shallow shoals, sand banks and irregular depths. Such characteristics, combined with the increasingly heavy traffic volume, render it vulnerable to collisions and pollution. Given the economic dependency of the littoral states on the Straits, they cannot afford to have the sea lane suffer from an incident that may jeopardize its ‘health’ or disrupt its activities. Underlining the economic dependency of the littoral states on the Straits, 70% of Malaysia’s fishermen are concentrated along the coastline and islands in the Straits, reaping more than 380,000 tons of fish estimated at US$0.32 billion annually. Many of Malaysia’s marine resorts and tourist spots are located along the Straits, contributing significantly to its tourism income. In addition, there are independent power plants located in the vicinity, which are dependent on water intake from the Straits. Singapore’s maritime sector is its economic lifeline; hence closure of the Straits to shipping due to pollution from an oil spill would cause severe repercussions to its economy. All these vital economic activities require that the Straits be pollution-free. It is no exaggeration to state that since the Straits act as an economic lifeline to the littoral States, the waterway needs to be guarded from pollution threats.

A coordinated and cooperative approach by the stakeholders is essential to manage the Straits’ environment. This requires a holistic approach including improving maritime services, boosting navigational safety and security, promoting marine environment protection, and advocating the sustainable development and utilization of the coastal and marine resources of the Straits. It is thus important that stakeholders promote, build upon and expand cooperative and operational arrangements, especially at the littoral states level, to strengthen capacity building among them to address environmental threats to the waterway.

Underlining the dramatic growth in traffic in the waterway, the number of ships reporting to the Ship Reporting System (STRAITREP) [1] in the Straits increased from 43,965 in 2000 to 62,621 in 2005 [2]. Correspondingly, the size of ships traversing the Straits has also increased, as seen in Table 1. Such growth brings with it higher burdens and costs to the littoral states to provide the commensurate maritime infrastructure to ensure navigation safety to the burgeoning traffic and to protect against marine pollution. In addition, post 9-11 fears heightened perceptions of risk in the Straits, resulting in the categorization as a ‘war risk zone’ by the Lloyd’s Market Association (LMA), on grounds of the perceived threats of piracy and terrorism in the area [3].

Table 1: Annual shipping traffic traversing the Straits of Malacca by types of ships

Since 9-11, many steps have been taken to improve security in the Straits. These include the MALSINDO coordinated patrol by the navies of the littoral states, the ‘Eye in the Sky’ air surveillance over the Straits, the creation of the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA), and increased patrols conducted by the littoral states.

The navies of Singapore and Indonesia

hold a joint exercise in August 2006

The improvement of security in the Straits is evidenced in the sharp decline of piracy cases in the waterway. The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) reported that there were 18 attacks in the Straits in 2005 compared to 38 in 2004. Not a single incident of piracy was recorded by IMB between the first quarter of 2005 and January 2006.

The heavy costs to protect the Straits from pollution, to improve navigational safety and to boost security have led the littoral states to call for the sharing of costs amongst users. While there is no authoritative figure on the amount which the littoral States have spent to facilitate all these, the estimated US$70 million which Malaysia alone spent between 1990 and 2000 to upgrade navigational facilities in the Straits is indicative of the heavy costs to the littoral States.

A Proposal for Burden Sharing: The Littoral States and International Users

The idea of burden sharing between the littoral states and international users has long been mooted in various conferences and forums. However, no mechanism has been framed and accepted by the parties, and no serious attempt has been made to move beyond the preliminary discussion stage.

The need for burden sharing to maintain the Straits was emphasized by the littoral states at the IMO Meeting in Jakarta on 7–8 September 2005 and extended during the recent Kuala Lumpur (KL) Meeting. This underlines the growing concern with rising costs and brings into focus the underlying frustration that the international community has not matched its heavy usage of the waterway with assistance to lessen the financial burden.

The littoral states face heavy and growing financial burdens to meet international expectations to assure safe passage in the Straits. An official of Aegis, the security and intelligence agency that acts as a consultant to LMA, estimated that the littoral states have invested over US$1 billion for equipment and training to improve security. This helped boost security in the area and convinced LMA to drop the Straits from its war-risk list, but the littoral states continue to face financial demands to guarantee security in this crucial body of water.

Such burdens are particularly felt by Indonesia, which faces heavy pressure to allocate financial resources to other socio-development priorities. While maintaining its position, together with Malaysia, that the Straits is not an international waterway, it recognizes its use for international shipping in accordance with the principle of innocent passage spelled out in UNCLOS. Indonesia also welcomes international cooperation in the Straits, as provided through Article 43 of UNCLOS, especially in the area of safety of navigation. Such a call is warranted as many of the navigational aids in place in need of maintenance and upgrading are located on the Indonesian side. In calling for international support to maintain and improve navigation safety in the Straits, Indonesia has called for international burden sharing as provided for by the Article to be enhanced and expedited [4]. From its perspective, any discussion of the subject should include both the littoral and user states, and should never undermine the sovereignty of the latter.

An Indonesian navy ship patrols the Straits

However, recent encouraging signs suggest that the idea of burden sharing is gaining momentum. There was increasing consensus among stakeholders at the KL Meeting to cooperate to ensure security in the Straits. The meeting concluded with governments, shipping industry leaders and maritime officials from 31 nations agreeing to provide equipment, training and funding to finance various projects to ensure that the Straits remain open and secure. Projects range from the removal of shipwrecks to tackling oil spills in the crucial passageway. The agreement is testimony to the growing recognition by the international stakeholders of the need to cooperate with and help the littoral states to maintain the Straits for the common good.

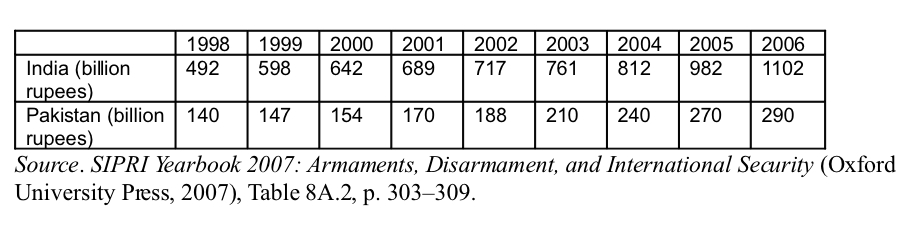

The littoral states could not have been other than pleased at these developments, and at the willingness of China and India, fast emerging as global economic powerhouses whose reliance on the Straits has grown in tandem, to help maintain the Straits. According to Sekimizu Koji, Maritime Safety Director of IMO, the two have expressed interest in contributing to the maintenance and recovery of navigational aid equipment in the Straits. The time is indeed ripe for substantive efforts by the relevant parties to realize burden sharing in the Straits.

Japan’s Contribution towards Maintenance of the Straits

Although international users have generally been lukewarm about extending financial assistance to the littoral states, only Japan, a nation with a heavy stake in the Straits, has consistently provided assistance to enhance navigational safety, mainly via funding from the Nippon Foundation through the Tokyo-based Malacca Strait Council.

At the KL Meeting, in a notable departure from its previously low-key stand on the subject, Japan urged user states to assist in the upkeep of the Straits. Suda Akio, Ambassador-in-charge of International Counter-Terrorism Cooperation at Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, explicitly stated that the user states of the Straits should share the burden of implementing programs and activities with the littoral states.

Mr. Ichioka Takashi, Managing Director of the Nippon Maritime Center, echoed Suda’s call for international users to help ensure safety in the waterway. Further accentuating Japan’s strong position on burden sharing, Ichioka stressed that Japan can no longer be the sole donor, and that assistance must reflect the proportion of the use of the Straits by vessels from international countries. In 2004 Japan was the leading international user of the Straits in terms of numbers of vessels (15 per cent) and by tonnage (18 per cent) [5].

For some decades, Japan alone has extended both technical and financial assistance to maintain order in the Straits. It has provided expertise and funding in areas such as navigational safety, maritime security and environmental protection. Japan contributed 400 million yen to set up a Revolving Fund in 1981 with the littoral states to combat oil spill in the Straits. It initiated the formation of the Oil Spill Preparedness and Response (OSPAR) Team based in ports along the waterway. It has also assisted in hydrological surveys and electronic mapping of the Straits, and infrastructure development projects such as the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS). Even its private sector has contributed significantly, to the tune of around 15 billion yen since 1968, in various Straits-related initiatives.

Private sector stakeholders such as shipping, petroleum, insurance and shipbuilding industries in Japan have voluntarily contributed financially to such initiatives. However, the level of such contributions has been decreasing due to a stiff business environment and to the stakeholders’ views that others with interests in the Straits should share the burden [6].

Japan has also extended support to recent programs such as the IMO-led Marine Electronic Highway (MEH) project [7]. Japan’s Coast Guard, the Ship and Ocean Foundation, the Japanese Association of Marine Safety, and Japan International Cooperation Agency have all contributed towards realizing this ambitious effort.

Beyond contributing resources to projects specific to the Straits, Japan has also chipped in to enhance security by initiating the Grant Aid Program for Cooperation on Counter-Terrorism and Security Enhancement, pledging US$70 million for the ASEAN Integration initiative during the Japan-ASEAN Summit Meeting in 2005, and setting up the Japan-ASEAN Integration Fund which can be used to fund efforts to maintain the Straits.

While Japan alone has provided financial assistance to maintain and manage the Straits, a growing number of countries among the international users of the Straits of Malacca have stated their willingness to share the burden of the littoral states. China is one country which has explicitly stated its support for the efforts of the littoral states to safeguard security. This position was reiterated by Ju Chengzhi, the Director General of the Department of International Cooperation at China’s Ministry of Communications at the IMO Meeting in Kuala Lumpur. He expressed China’s readiness to participate in regional and international mechanisms of cooperation to ensure safety in the Straits and to contribute its share to maintain and enhance safety of navigation, maritime security and environmental protection. Specifically, China volunteered its strength in hydrographic survey and in navigational aids, and to provide tangible support to the littoral states in training, technical exchanges and capacity building.

Another rising economic power, India has also volunteered its capacity and experience in various areas of cooperation to support regional efforts to ensure safety and security, as mentioned by Insp. Gen. Basra Surinder Pal Singh, the Deputy Director General of the Indian Coast Guard at the IMO Meeting in Kuala Lumpur. The United States has also put on record its willingness to contribute to efforts towards attaining that objective, with the consent of the littoral states [8]. Korea, through its Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, has contributed financially to the IMO’s Marine Electronic Highway (MEH) preparatory project and has expressed its commitment to contribute to the MEH demonstration project. The rising chorus of major international users of the Straits expressing willingness to assist in its upkeep is a welcome development toward a meaningful and workable mechanism of burden sharing.

Burden Sharing in the Straits: Issues to Consider

There are various issues to consider before a workable burden sharing mechanism can be put in place. The most crucial question is who should share the cost of maintaining the Straits? In answering this question, the term ‘users’ should be clearly defined, bearing in mind that the beneficiaries of the Straits include enterprises engaged in trade, shipping, port, oil and gas, fishing and marine leisure/tourism. Some users have expressed support for such an initiative, as exemplified by the willingness of the International Association of Independent Tanker Owners (INTERTANKO) to pay for improved safety measures [9].

It should be noted, however, that a private fund to help maintain the Straits should take the form of a multi-lateral body whose members or contributors would have the discretion to dictate the amount of funds to be used in specific initiatives. Naturally, they would demand accountability and transparency in the way the burden-sharing fund is managed, before committing to such scheme. In garnering international participation, perhaps the littoral states could work with the IMO as arguably the organization with the most clout to work out burden-sharing mechanisms consistent with international best practices. A workable burden-sharing model would be one that is conceived after taking into account existing legal regimes and jurisdictional complexities. It should also consider the views of the user states and be non-discriminatory in its imposition of tax or surcharge.

It is envisioned that such a fund would be based on the spirit of the Jakarta statement made at the IMO Meeting in Jakarta in September 2005 that called for cooperation between the user and littoral states in the use and maintenance of the Straits. However, finding points of convergence between the littoral and user states on what model to use is complex and challenging.

This was underlined during the meeting of user states in February 2006 organized by the United States Coast Guard in Alameda, California, which discussed the ways and means to burden-share the initiatives on security, safety and environmental protection in the waterway. Not only did the meeting fail to articulate a model to realize the concept of burden sharing in the Straits, it pointed to a glaring difference of perspective on what constitutes “burden sharing” among the user states. The littoral states viewed the concept based on the sharing of financial resources in navigational safety and environmental protection issues, while the United States, as a major user state, would like to see the mechanism of sharing take into account security protection, particularly to address the threat posed by terrorism and piracy. The political dimension compounds the difficulty of burden sharing further, as highlighted by Japan’s reluctance to share the role of being an active donor with other user states with growing interests in the Straits, in particular China; and the objection by several littoral states to the US Regional Maritime Security Initiative (RMSI) proposal to “internationalize” management of the sea lane.

Although the United States has vigorously aired its strong opposition to toll-type charges in the Straits, it has always welcomed cooperation amongst the users to maintain the Straits. It has acknowledged that given the rising traffic volume in the waterway, it would be neither fair nor reasonable to lay the burden of maintaining security exclusively on the shoulders of the littoral states [10]. The United States agrees that there should be room for other stakeholders to help them relieve the burden, and has expressed its willingness to contribute to such efforts and help in capacity-building initiatives, with the acquiescence of the littoral states. It is hoped that such an offer can be extended beyond the realm of security and can provide a solid footing on which a workable and sustainable burden-sharing model can be explored.

It is imperative that the littoral states work with the international community and agencies to explore and realize a funding mechanism to share the burden of managing the Straits. Such a framework must be consistent with Article 43 of UNCLOS, which stipulates that the user and littoral states of a strait for international use should cooperate in efforts to maintain navigational safety and solve pollution-related problems. With users becoming aware of the need to set aside differences and come to terms with the need for a collective approach, there is much to be optimistic about realizing burden sharing in the Straits.

A Cruise ship passing through

the Straits

Towards a Workable Burden-Sharing Model in the Straits

As various forums have suggested, the trend in traffic volume can provide an equitable basis for constructing a burden sharing mechanism in the Straits, in line with the ‘user pays’ concept.

The task of setting up and managing the burden sharing mechanism would best be assigned to a secretariat comprised of representatives from the three littoral states and others from the spectrum of stakeholders. Allowing the littoral states to lead the initiative in this challenging task would symbolize the international community’s affirmation of their sovereign rights over the Straits. This is crucial both in getting the scheme off the ground and in assuring efficient management and administration. The secretariat could be modeled after the Tripartite Technical Experts Group (TTEG), a forum made up of the representatives of the littoral states set up to address safety of navigation and environmental protection issues in the Straits.

A further cue can be taken from the Japanese model of financial assistance. The existing Straits of Malacca Revolving Fund, which Japan helped to establish, could be used as a basis for burden sharing expanded to cover other user states. The Fund is a glowing example of cooperation between the littoral states and a user state in maintaining the Straits, and could provide an excellent model for a burden sharing mechanism.

Another sound framework is the proposed special fund to finance navigational aids in the Straits, an idea which has been recently mooted at the IMO. The fund, established on the existing and evolving cooperative mechanism platform between the littoral states and the user states, aims to provide sustained financing for efforts to make navigation in the Straits safe and to protect its environment.

Perhaps a similar fund for burden sharing could be established based on the template provided by the Straits of Malacca Revolving Fund and the framework proposed for the special fund for navigational aids, with appropriate adjustments. Contributions to the burden sharing fund could come from both the littoral states and international users, with quantum based on factors such as gross tonnage of vessels, volume and value of cargo, hazard level of cargo and ships, frequency of use, and other cargo and ship-related functions.

In determining the best burden sharing mechanism, the term ‘burden sharing’ itself should include the sharing of in-kind resources such as technology, equipment, logistical support and management and technical expertise. Even socio-economic assistance should be welcomed, for example in fighting the scourge of piracy whose roots are often traced to ‘land-based issues’ such as poverty, unemployment and lack of education.

Most important, the burden sharing mechanism should not in any way undermine the inviolable sovereignty and territorial integrity of the littoral states of the Straits as the ultimate custodians of the waterway. The primary responsibility of maintaining and managing this vital and strategic waterway unquestionably lies with them, and should remain so.

Nazery Khalid is a Research Fellow at the Maritime Institute of Malaysia (email: [email protected]). For other articles on the Straits and the South China Sea, see Khalid, Maitra,

and Rosenberg.

The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s and do not reflect the official position of his institute or that of the Malaysian government. Posted at Japan Focus on November 17, 2006.

For an alternative perspective on burden sharing in the straits see Mark J. Valencia, Cooperation in the Malacca and Singapore Straits: A Glass Half-Full

Notes

[1] STRAITREP is a mandatory reporting system under which the statistics of ships traversing between the Vessel Traffic System (VTS) centers established in Port Klang and Tanjung Piai along the Malaysian coast bordering the Straits of Malacca are captured.

[2] Marine Department, Peninsular Malaysia statistics.

[3] LMA, an insurance trade association based in London acting for its members in the Lloyd’s underwriting market, issued a list on 20 June 2005 via its Joint War Committee detailing procedures for amending the war risk areas used on marine hull war risk contracts. The list was a sweeping overhaul of its listed war-risk areas, provided new guidelines to underwriters listing a total of 21 areas worldwide in jeopardy of “war, strike, terrorism and related perils”. The areas specified included the Straits of Malacca and adjacent ports in Indonesia. Other countries on the list include Iraq, Somalia and Lebanon. The Straits was taken off the list in August 2006.

[4] Oegroseno, A.H. (2004), ‘Straits of Malacca and the challenges ahead: Indonesian point of view’, in Basiron, M.N. & Dastan, eds., Building a Comprehensive Security Environment in the Straits of Malacca, (Kuala Lumpur: MIMA), p. 28–39.

[5] Nippon Maritime Center survey, 2004.

[6] Sakurai, T. (2004), ‘Straits of Malacca and the challenges ahead: Japan’s perspective’, in Basiron, M.N. & Dastan, eds., Building a Comprehensive Security Environment in the Straits of Malacca, (Kuala Lumpur : MIMA), p. 51.

[7] MEH is an innovative marine information and infrastructure system that integrates environmental management and protection systems and maritime safety technologies. Funded by the World Bank, the US$17 million conglomeration of systems and technologies aims to enhance maritime services, improve navigational safety standards, integrate marine environment protection and promote sustainable development of coastal and marine resources. Besides Japan, Korea also contributed a sum of US$1 million to the project.

[8] Doughton, T. F. (2004), ‘Straits of Malacca and the challenges ahead: The U.S. perspective’, in Building a Comprehensive Security Environment in the Straits of Malacca, edited by Basiron, M.N. & Dastan, A. (Kuala Lumpur: MIMA), p. 42.

[9] Hamzah, B.A. & Basiron, M.N. (1996). The Straits of Malacca: Some Funding Proposals. Kuala Lumpur: MIMA. pp. 43–45.

[10] Doughton, T.F., p. 42.