Nakano Akira

When I got off the train, a sign on the platform informed me that Seoul lies 56 kilometers to the south and Pyongyang 205 km to the north.

This is Dorasan Station, close to the demilitarized zone (DMZ) demarcating the two Koreas. It is the northernmost station in South Korea on the Gyeongui Line. It connects North Korea’s Sinuiju, near the border with China, and South Korea’s capital, Seoul. The station is located in an area in which the South Korean military controls civilian traffic. Only three trains come this far each day. Passengers must provide ID and allow their belongings to be searched by military police.

Until a few years ago, the area was carpeted with land mines. They were removed after the first summit meeting between the North and South Korean leaders in 2000.

An upshot of the meeting was to restore part of the Gyeongui Line that was destroyed during the 1950-53 Korean War. The station was constructed five years ago.

In May, during a trial run, a train crossed between the two Koreas for the first time in 56 years. It was a symbolic moment.

Extending the track to the North represented a new phase in efforts to achieve some sort of reconciliation between the divide.

A planned summit between North and South Korean leaders has been postponed to early October due to flooding in the North.

South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun was originally scheduled to take the route running along the Gyeongui Line to reach Pyongyang on Aug. 28. He apparently wanted to emphasize the benefits of exchanges between North and South Korea.

What brought me here?

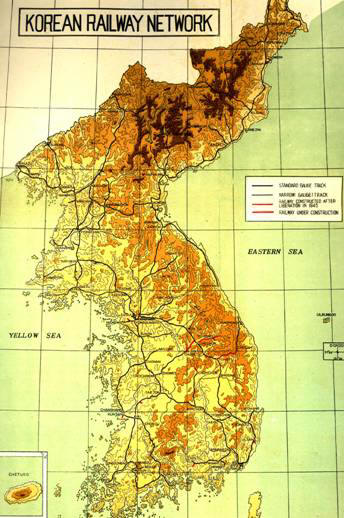

When I studied when and how Japan colonized the Korean Peninsula, I learned that building railways formed a major part of that process. The Gyeongui Line is said to have played an important role.

Shadows of colonization, the division of North and South, and reconciliation. To start the journey of learning about the occupation, I wanted to see first-hand the symbolic place where history looped back in several layers.

Flashpoints for conflict

In Seoul, I visited University of Seoul professor Chung Jae Jeong, who wrote a book titled “Japanese Imperialism and Korean Railroads.”

When I asked him if railways had made life easier for Koreans, his face became grim and he answered as follows:

“From Korea’s point of view, the Imperial Japanese Army brought railways with it, beginning a period of deprivation and oppression. Japan thought the Korean Peninsula was strategically crucial to its military and laid railways as tools to control the peninsula. The Russo-Japanese War was, in a way, a war over railways.”

Chung went on to explain that the great powers viewed railways as key to expanding their areas of influence because of the ease with which military personnel and goods could be transported in bulk.

Japan and Russia battled over railroads located in northeastern China and the northern part of the Korean Peninsula. The two countries couldn’t reach a settlement through negotiations and that was part of the reason they fell into conflict, Chung said.

After the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Russia scrambled to expand its own rail network. That included obtaining right of passage from the Qing Dynasty for the Chinese Eastern Railway that traversed northeastern China almost to Vladivostok, and its south Manchurian branch line from Harbin to Lushun.

Japan also focused on acquiring control of the Gyeongui Line and the Gyeongbu Line that connected Seoul with Pusan at the southern tip of the country. That was because the rail link allowed movement up and down the peninsula. Japan gained right of passage for the Gyeongbu Line after the First Sino-Japanese War and started construction in 1901. As tensions grew with Russia, Japan rushed to complete the railway. The government of the Korean Empire wanted the Gyeongui Line to be built with its own people, but the project stalled due to a lack of funding.

Public records from that time clearly show the Japanese government’s intentions. For example, in a document that then Foreign Minister Komura Jutaro submitted to then Prime Minister Katsura Taro in 1902 for Cabinet approval includes the following:

“If Japan constructs the Gyeongui Line on our own and connects to the Gyeongbu Line, all major railways will be in the hands of our empire, in effect keeping Korea under our influence.”

The following year, the Cabinet in Tokyo adopted a negotiating policy with Russia that aimed to have Russia promise not to block future Japanese expansion of railways in Korea toward the southern part of Manchuria. In other words, Japan aspired to extend railways from the Korean Peninsula to northeastern China to expand its sphere of influence.

The Russo-Japanese War began in February 1904.

Before the war, the Korean Empire announced it would be “neutral” in the conflict. However, Japan ignored the statement and sent advance troops to Incheon two days before declaring war on Russia.

With the inclusion of reinforcements, more than 10,000 soldiers flooded the capital and its immediate vicinity. In practice, Korea was occupied by Japan. About two weeks after the start of hostilities, Japan and Korea signed a protocol. Under this document, Japan got Korea to allow it to expropriate militarily sensitive areas on an as-needed basis. In other words, the Imperial Japanese Army gained the power to obtain whatever land it deemed necessary.

Regarding the pending Gyeongui Line, Japan notified the Korean Empire that it intended to build a military railroad. A railway battalion was dispatched to begin construction.

War the catalyst for colonization

To visit the site where railway and colonization history overlap, I traveled to Yongsan-gu in Seoul.

The district to the east of Yongsan Station is blank on Korean maps. Now, a massive U.S. military base occupies the area that is lined with barbed wire, concrete and brick walls along the roads.

Japanese troops expropriated land throughout the area during the Russo-Japanese War to build military facilities. Even now, 100 years later, Koreans still cannot enter the area freely.

Why did the Japanese army choose Yongsan?

Seoul National University researcher Kim Baek Young used an old map to explain. Yongsan Station, the gateway to the region, was a railway junction on the peninsula at that time, and the Gyeongui Line and other rail arteries extended from it. It was located where the army could easily keep watch on the Korean imperial palace.

“The Japanese army built a massive military base where it could easily monitor the king and move to other places on the peninsula by rail,” said Kim.

The Gyeongbu Line was another important route that was completed in January 1905. A ferry service to and from Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, also started the same year. In April of 1906, the entire Gyeongui Line was operational.

In only a few years, during which the Russo-Japanese War was waged, Japan had built a railway that extended across the peninsula almost into northeastern China, a distance of some 950 km.

The distance is approximately the equivalent of Tokyo to Shin-Yamaguchi on the Tokaido-Sanyo Shinkansen train line.

Previously, the army had resorted to horses and other means to transport weapons and food by land. The railways enabled mass transport to China’s doorstep.

The Japanese army not only built an artery to move troops and supplies, but it also set up troop encampments as an excuse for transporting goods to the front lines and security along the railways. Along the way, it stripped Korean police of their authority in the country’s capital.

Even after the war against Russia ended, Japanese troops did not leave. An army contingent estimated at around 30,000 soldiers, or about two divisions, stayed on. Furthermore, it expropriated massive areas of land mainly along the railways in Daegu and Pusan for key military bases.

During my research, I met Seo Min Kyo of the truth commission on pro-Japanese anti-Korean activities in an office in Seoul.

“When the Russo-Japanese War began, Korea essentially fell into the hands of the Japanese army, and colonization developed,” he said. That is why the commission covers the period of Japan’s colonial occupation from the start of the Russo-Japanese War in February 1904 to Korea’s liberation in August 1945.

In other words, South Korea considers Japanese colonial occupation to have begun with the Russo-Japanese War, not from the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty signed in 1910.

Rural labor unrest triggers protests

How was railway construction viewed by the Korean people?

In early July I visited the Independence Hall of Korea in Cheonan City that was built 20 years ago as controversy raged over the content of Japanese history textbooks. Outdoor exhibits depicted life-size dolls of Japanese soldiers holding guns and crucifying Korean people. The panel said the display would continue until the end of August. It explained, “This is a reproduction of how patriotic Koreans were executed in 1904 for destroying a railway built by the Empire of Japan for the invasion of Korea.”

The three Koreans executed by firing squad in public near the Gyeongui Line in the country’s capital in the midst of the Russo-Japanese War are honored as loyal soldiers who resisted Japan’s colonization. A photograph of the execution scene appears in history textbooks.

Construction of the railways did not just involve expropriation of farmland. Japanese soldiers and businesspeople were mainly supervisors and local farmers who were, for the most part, coercively rounded up did the physically demanding work. Such methods invited public antagonism and hatred, and railway projects were targeted for sabotage by rebellious farmers and others.

The Japanese army was having problems controlling the rebellion, so it issued orders to “punish with death” those who attacked the railways and who harbored such people. Some executions were carried out.

In Anyang City, a suburb of Seoul through which the Gyeongbu Line runs, the name ” Ito Hirobumi ” is carved into a stone monument standing on a small hill overlooking the city. According to the inscription, local resident Wong Tae Woo learned that Ito was passing through Anyang by train on the Gyeongbu Line in November 1905. He threw stones at the train, injuring Ito. Wong was thrown into prison and tortured.

The stone monument was erected 15 years ago by local residents to pass along the local “hero’s achievement” to younger generations.

Ito, a former prime minister, was visiting the country as an envoy to press the Korean Empire to sign the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty (Eulsa Treaty) that would strip Korea of its diplomatic rights and make it a protectorate of Japan.

On Aug. 22, 1910, 10 months after Ito was assassinated by Korean activist An Jung Geun, the Korean Empire held its last imperial conference, approving the signing of the Annexation Treaty. The conference room used to be in a corner of the Changdeokgung Palace complex, now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

A plaque there refers to it as “the place of misfortune where the Korea-Japan Annexation Treaty was adopted.”

In the following year, construction work finished on a bridge spanning the Amnok River that separates the Korean Peninsula from China, connecting Pusan to northeastern China by rail. Japan began a headlong rush to wage aggression with China.

Fact File: Truth Commission on pro-Japanese anti-Korean activities

The commission was established in May 2005 with a special law under President Roh Moo-hyun’s administration to investigate collaborators and their activities during Japan’s colonial rule. The commission has 11 members, including scholars and lawyers. It also has research staff. A separate commission, called the Investigative Commission on Pro-Japanese Collaborators’ Property, was set up to look into assets held by pro-Japanese collaborators as a result of their dealings with the Empire of Japan. It confiscates assets from descendants and put them under state control.

* * *

Fact File: Japan an unusual colonizer

Until the discovery of the “New World” in the 15th century, colonies referred to new cities and towns created by ethnic groups and others who emigrated to another land. Now, the definition includes external territories under the control of a nation. From the late 19th century, European nations and the United States competed to acquire colonies in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific to access raw materials and sell their products. Japan is a rare example of a country that colonized neighboring states with which it had maintained relations since ancient times.

This is a slightly abbreviated version of an article that appeared in the International Herald Tribune/Asahi Shinbun on September 28,2007 and at Japan Focus on September 29, 2007.