Okinawa – Rising Magma

By Miyagi Yasuhiro (Councilor, Nago City, Okinawa)

Koizumi’s Japan enjoys the warmest of relationships with Bush’s US, for the very good reason that Koizumi has proved himself willing, even enthusiastic, to deliver what Washington requires – uncritical support in general, continuing provision of facilities for the US military in Japan, and Japanese boots on the ground to support the American mission in Iraq. On one significant issue, however, Koizumi has failed to deliver: the 1996 promise to replace the antiquated and inconvenient facilities of Futenma Marine Air Station, that now sits uncomfortably in the middle of the bustling township of Ginowan in the middle of Okinawa island, with a new facility in Northern Okinawa, to be built on the coral reef offshore from the fishing village of Henoko, in the township of Nago. It was a relatively remote and backward area, and Tokyo assumed it could rely on persuasion and financial inducements to overcome local opposition. It got rid of the Governor, the stubborn scholar and constitutionalist, Ota Masahide, in 2000, installing in his place a conservative figure expected to be more pliable, and poured in money to soften up the local opposition. Despite everything, however, it has not prevailed. In October 2005, the plan to construct the base on the reef had to be abandoned. Koizumi admitted the opposition had been too great. The Japanese state had, in effect, been defeated, by a coalition of fishermen, local residents, and citizens. One of the most remarkable events in recent Japanese history passed without notice by the media and the pundits.

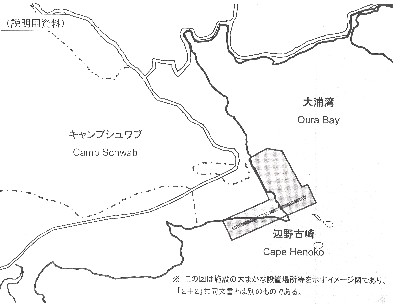

While conceding that defeat, however, Tokyo decided to press for an alternative site a very short distance away from the one it abandoned, in the shallow waters offshore from Cape Henoko, in Oura Bay. Washington agreed. As in 1996, Tokyo plainly intends to use persuasion and inducement and hopes it will not be necessary to resort to force, This time, however, even the Governor installed in 2000 as the best man to advance the Tokyo agenda, Inamine Keiichi, has declared himself fundamentally opposed to the new plan, and surveys show Okinawan opposition running at over 70 per cent, higher than at any time in the 1990s. Governor Inamine has spoken often of the magma rising and Okinawa being on the brink of an eruption. Such a catastrophe is nearer now than ever before.

Miyagi Yasuhiro has been a key figure in the movement of opposition to militarization in Okinawa for the past decade. Here he issues a somber warning to Tokyo and Washington: the Okinawan people will not be overcome, the base will not be built.

Over the names of the Foreign and Defense Secretaries of Japan and the United States (2+2), a document with the provisional title “The Japan-US Alliance – Future Oriented Change and Reorganization,” dated 29 October 2005, sits on my desk. Asked to write my impression of it, I try again and again to read it, but my gloom is so deep that it is hard to bring myself to do so. This “Agreement” has been described as an “Interim Report,” as if there might be also a “Final Report,” but the words “Interim Report” are nowhere to be found in it. It was drawn up without any consultation whatever with the local governments affected by it and, by calling it “Interim Report,” the Japanese government wants public opinion to believe, mistakenly, that there might be changes in the “final version” still to come.

From its opening paragraphs the Agreement reaffirms “newly emerging threats” that might affect the security of the countries of the world and “issues giving rise to uncertainty and instability” in the Asia-Pacific. Yet it is the implementation of the Agreement itself that constitutes a threat and a problem.

On the question of the shift of Futenma Marine Air Station that is a major focus of attention, the major mainland newspapers carried editorials backing the Agreement. Nihon keizai shimbun (9 October) carried an editorial about “overcoming the confrontation on the Futenma issue by the exercise of political responsibility” and hinted at the introduction of police force against the opposition movement by residents in accord with that political resolve. Mainichi shimbun (27 October) wrote: “surely this time at last we will be able to see a resolution” and referred to the Schwab area as if it were unpopulated, describing it as a “step forward” for the base to be moved “from Futenma, where it sits amid a crowded residential area, to the Camp Schwab vicinity.”

The mass media tends not only not to learn from history but to shamelessly distort contemporary events. To us Okinawans, who have experienced the catastrophe of the last war and the subsequent US military occupation, this country, that is unable to comprehend the reaction by South Korea and China when the Prime Minister worships at Yasukuni where the leaders of the aggressive war are enshrined, seems to have lapsed into distorting narrowness of vision.

Prime Minister Koizumi may think that, so long as there is the Japan-US alliance, all will be well, but it would not be out of character for Bush’s America to provoke a “Tonkin Gulf Incident” (when fabricated attacks on a US naval vessel in the Gulf of Tonkin in August 1964 were used as pretext for the US to begin bombing North Vietnam) in the Taiwan Straits. Clearly cognizant of the existence of China, this Agreement includes provision for merger of Japan’s Self Defense Forces with the US military. The isolation of Japan in East Asia resulting from total subordination to the US is dangerous in the extreme.

From 1996, Nago City where I live, and which contains the Marine Base of Camp Schwab, has been subject to an unbroken siege to try to force it provide an alternative base for Futenma.

The Futenma replacement facilities referred to in the present document are to be built in an L-shape linking the seas of Oura Bay across the Camp Schwab coastline. They will be characterized by “manifold concern to minimize any adverse impact on the environment.” In fact, the scale has been enlarged since the 1996 final report of SACO by lengthening the runway and adding space for parking planes. As usual, the US gets most of what it wants and the site will be easily capable of expansion to achieve 24-hour readiness status.

The proposed Henoko L-shaped facility

A national college of technology has just opened in the adjacent area and these plans are too much to bear for those connected with the school, including the students. In the coastal area designated for the construction on Schwab there are also historic remains and various cultural treasures, and sea turtles lay their eggs on its sandy shores. However much they might try to “minimize environmental damage,” the pristine quality of such an environment itself cries out against the threatened human intervention. At first, a sea-based location was chosen for construction, far from human settlement in order to minimize noise pollution, but that sea turned out to be home to the dugong, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) had to take the most unusual step of twice (at Amman in 2000 and Bangkok in 2004) issuing warnings against acts likely to damage its habitat. For eight years the matter remained deadlocked. The coastal site adjacent to human settlements now chosen as substitute for the sea-based site confronts a dark future of endless conflict between local residents and self-governing organizations, and the peace and environmental movements, on one side, and a government prepared to use force to settle the matter on the other. In order to implement the Agreement, the government is said to be considering passage of special legislation to remove from local governing authorities their powers under laws including the Public Waters Reclamation Law, the Environmental Assessment Law, and the Cultural Properties Protection Law. It shows not the slightest regard for national sovereignty, local self-government, or human rights. Make no mistake about it: the whole of Okinawa is going to resist.

What can the politicians who played the key role in reaching this agreement have been thinking? Do they want to contribute to destabilizing the Japan-US alliance? Even if the conditions attached by the US military made it difficult to accomplish the removal of the base to somewhere outside Okinawa, as the majority of Okinawans are demanding, they could at least have explored and made other, more realistic proposals. Instead, they have taken a proposal that had been deadlocked for eight years, and revived it as a zombie. Despite the fuss being made, the Camp Schwab proposal amounts in the end to nothing more than shifting the project by a few hundred meters. It is a farce pure and simple.

What we are witnessing is actually a plan that was drawn up by the US army in the 1960s, when it administered Okinawa, but which it could not then implement because of the political risks associated with local, Okinawan opposition. It is now revived because the Japanese government is now in charge and believes the opposition can be overcome.[1]

Most Japanese people see Okinawa as a military colony provided by Japan for the US military. A colony needs collaborators among the natives. However, the mayor of Nago City and the head of the Nago City Chamber of Commerce and Industry, who in the past undertook to collaborate and play the role of persuasion, having listened to the government’s explanation, now say that they will not be able to persuade the residents to accept the new plan.[2] When even self-styled collaborators find themselves unable to collaborate, colonial rule enters a critical phase. The suzerain country may in the end find itself called on to expose its true, violent character. I cannot help but think that the mainland mass media are playing the role of its advance guard. The outlook is bleak.

It is not just opponents of the US-Japan Security Treaty and ideological conservatives, i.e. proponents of the Treaty, that live in Okinawa. All of us here live face-to-face with harsh reality. For the sake of the Japan-US security treaty, our peace of mind and our safety is threatened. Why should it be that Okinawa alone has to shoulder “the burdens and costs?” [3] Our eight years of struggle have taught us to believe that it will not, after all, ever be possible to build a new base, whether at Henoko or Camp Schwab.

Following the end of the war sixty years ago, the bases were steadily expanded and reinforced under unbroken US military administration, and even when governmental powers were returned to Japan in 1972 they were maintained. Since the Cold War ended new threats have been found and the burden on us has grown. Surely this militarization, and the discrimination that we experience, cannot go on forever. Living in Okinawa, it is hard to resist being overwhelmed by depression.

In this situation, anything could happen, even an act of terror. Faced with an opponent who monopolizes the means of violence to such an unequal degree, it is understandable that the people insist on the right to possess means of resistance and to use them. I would not be surprised if acts of resistance were to occur tomorrow, in Nagatacho, Ichigaya, Kasumigaseki, or Okinawa. The present Agreement is not a prescription for dealing with “newly emerging threats,” but a device to stir up such threats.

Day 110 of the Henoko anti-base struggle

I had intended to end this essay by writing “Unless the farce is quickly ended, the spectators will become angry,” but it seems to me that the spectators are not angry. As one of the cast who happens to live in Okinawa (though ignored by the Japanese and American governments), I am angry, but the majority of the spectators either watch with half-dead eyes or laugh or yawn. Now that the political theatre (of the national elections of September 11, 2005) with its much ado about “assassins” and “winners and losers,” is over, there comes this farce conducted by politicians who pretend to be experts on security but actually plunge Japan into danger. Perhaps now the curtain will rise on a new drama, but if so it is likely to be the theatre of pain rather than spectacle. Still, I know that multiple lines of resistance will be drawn and many kinds of people will turn to struggle. I also know that people living ordinary, modest lives will face the situation wisely. Another day, another struggle – it is Okinawa’s destiny.

Miyagi Yasuhiro, born in Nago in northern Okinawa in 1959, was a central figure in the Nago City Plebiscite Promotion Council (later Council against the Heliport Base) from 1997, and from 1998 has been Nago City Councilor. He is also joint representative to the Dugong Protection Campaign Center and author of several works on Okinawa, the dugong, etc. Email: [email protected]

Translated by Gavan McCormack from the text of a chapter by Miyagi for a forthcoming Japanese volume to be published by Kobunken. Posted at Japan Focus December 4, 2005.

Notes

[1] Makishi Koichi et al., eds, Okinawa wa mo damasarenai, Tokyo, Kobunken, p. 108

[2] Mayor Kishimoto Tateo, after meeting Defense Agency officials on 27 October, made a statement about the “impossibility of persuading residents,” but on 9 November, after meeting with the head of the Defense Agency, Nukaga Fukushiro, said he “would like to be able to achieve agreement.”

[3] After the Bush-Koizumi meeting in Kyoto on 16 November, Koizumi said, “to enjoy the benefits of peace and security, some burdens and costs are necessary.”