Rivers, Dams, Cargo Boats and the Environment

Milton Osborne

When the Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) released its list of the world’s top ten rivers at risk in late March, attention in

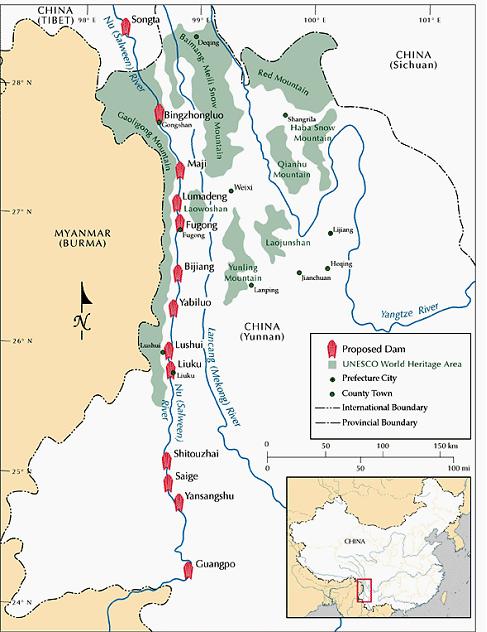

Map 1: Proposed dams along the Nu (Salween)

Source: International Rivers Network

In two Lowy Institute Papers, River at risk: the

The first of these issues relates to the controversies associated with plans for the construction of dams on the Salween River, the last free-flowing river in Southeast Asia; the second to developments associated with the greatly increased navigation of the Mekong River now taking place between southern Yunnan and northern Thailand. In the case of the

Long neglected outside the circles of advocacy Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), the environment has increasingly become an issue of political importance in

The

Like the Mekong, the Salween River rises in Eastern Tibet at a height above 4,000 metres, where for several hundred kilometres it runs parallel to both the Mekong and the Yangtze, forming part of what is known as the ‘Three Parallel Rivers’ region. After passing through

Although the second longest river flowing through

Photograph 1: Salween at Ban Sam Laep

Of great importance to any discussion of the

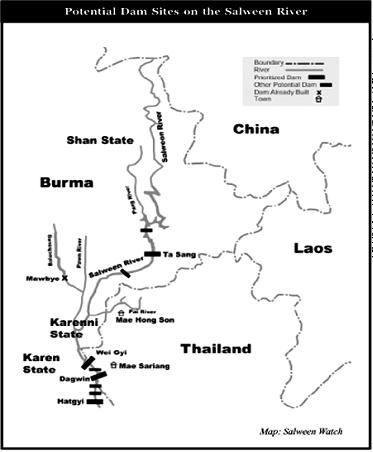

Map 2: Potential dam sites of the Salween River

Among advocacy NGOs concerned with environmental issues there has been considerable focus on the Three Parallel Rivers region already mentioned. This area was inscribed on the list of World Heritage sites in 2003 for its identity as the ‘epicentre of Chinese biodiversity’ which is ‘also one of the richest temperate regions of the world in terms of biodiversity’.[6] On the basis of a map published by the International Rivers Network, the designated Heritage area does not include the Nu itself, but rather is located close to the river’s right, or western bank, as well as taking in areas further east, close to the Mekong and the Yangtze. (See Map 1 entitled ‘Proposed dams along the Nu (

In both

What is planned, and why?

The possibility of constructing dams on the

While

Among the dams planned for

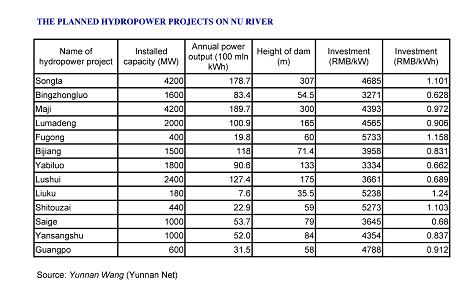

Details of

It appears that a detailed proposal to build 13 dams on the upper section of the Nu was first put forward in 1999, by the State Development and Reform Commission. This were then elaborated in August 2003, when officials in

To the considerable surprise of outside observers, the announcement that dams would be built on the Nu brought an unprecedented series of protests from within China itself, including from the Chinese Academy of the Sciences, two prominent Chinese NGOs, the China Environmental Culture Association and Green Watershed, as well as some prominent individuals. And an even greater surprise followed, given

So, despite the unavailability of firm information about

A detailed report of a journey along the course of the Nu in

In his article Thomas provides information on the planned size of two of the dams, those at Maji and Songta, that is consistent with the details provided by the International Rivers Network, by far the most active of all international advocacy NGOs in relation to river issues (see Table 1). At Maji, located ‘north of the riverside town of

In contrast to the sizeable body of literature that exists discussing, and frequently condemning, the Chinese dams built on the Mekong for their predicted long-term detrimental environmental effects on the countries downstream of China, there has so far been little material published that analyses what dams built on the Nu will mean for the countries downstream of China: Burma and Thailand. The suggestion in the Asia Sentinel article cited above that the Chinese dams ‘are expected to raise government hackles in

There is little basis on which to assess China’s likely reaction to the protests that have been lodged in relation to the dangers to the heritage status of the proposed dams to be built in the Three Parallel Rivers region. As already noted, these protests have come from within

Before the monitoring mission made its visit to the Three Parallel Rivers region,

Following their visit to the Three Parallel Rivers region, the two-person monitoring team, composed of a representative each from UNESCO and the World Conservation Union, reported that the Chinese authorities with whom they consulted indicated an intention to reduce the area of the heritage area that had been inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2003 by approximately 20%, and more particularly that:

While the

noted the repeated commitment of accompanying officials to applying stringent Chinese laws and policies towards protection of the World Heritage Site, the evidence of intrusions from mining, tourism and proposed changes to inscribed boundaries and the lagging release of hydrodevelopment plans, continues to raise concerns about the future integrity of the inscribed property. The existing mining operations within some of the inscribed properties also suggest the possibility of listing the property on the List of World Heritage in Danger.[17] Mission

At the Thirtieth Session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, in July 2006, and in the light of the monitoring mission’s report, the committee noted that although Chinese officials had given assurances that any future dams would not affect the World Heritage Site, this could not be corroborated since the mission’s members were not given any Environmental Impact Assessments or maps relating to the proposed dams that China intends to build. In addition, ‘evidence from maps, the inspection of hydro-power development exploratory works, unclear boundaries and advice on proposed dams in the vicinity of the World Heritage property suggest that direct and indirect impacts of dam construction on the property may be considerable’. Concluding that China’s positive conservation measures ‘are regrettably overshadowed by grave concerns about the, as-yet unreleased, plans for hydro-development’, the Committee called on China to submit a report by 1 February 2007 giving details on its plans for dams within the Site area.[18]

To date, I have not been able to find evidence that

In the end the World Heritage Convention (sic) did not use its ‘yellow card,’ giving everyone a chance to rest a little easier, though we hope that at the next convention we will hear some good news about the Three Parallel Rivers Region.

Yet to conclude in this Panglossian fashion that ‘all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds’ may neither be justified, nor a reliable index of central government thinking on environmental issues. The World Heritage Committee appears to act in an essentially apolitical fashion in placing sites on its endangered list, and there is no certainty that it will not be ready to act in the same way in relation to the Three Parallel Rivers region. At the same time, and just as Wen Jiabao’s decision in 2004 to halt plans for the construction of 13 dams on the Nu was a surprise to many observers, the emphasis placed by the Chinese premier on environmental questions in his recent address to the National People’s Congress on 5 March suggests that it cannot now be assumed that the central government will simply disregard the World Heritage Committee’s concerns.

Until the overthrow of the Thaksin government in September 2006,

It was not until December 2005 that EGAT and the Burmese Ministry of Electric Power signed a Memorandum of Agreement for the construction of a dam at Hutgyi, in

The plans for the Salween dams, as they stood before the overthrow of the Thaksin government in September 2006, attracted vigorous criticism from advocacy NGOs, particularly those concerned with human rights, but also in relation to environmental issues. Prominent opposition political figures, such as former chairman of the Thai Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Kraisak Choonhavan, were also active in condemning the planned dams.[21] The Tasang dam will, when constructed, be the largest dam in

Both the Tasang and

Human rights issues, as these relate to ethnic minority dissidents, have also been raised in the case of the planned Hutgyi dam. The area in which the dam is to be built is home to members of the Karen minority, who have long opposed Burmese control, and there have been reliable reports of the Burmese government engaging in forced relocation of the population in the area as roads are built and villages are destroyed to make way for large-scale agriculture. One indication of the problems in the general Hutgyi area has been the increased flow of refugees across the border into

Following the military coup that ousted former Prime Minister Thaksin, the Energy Minister in the new interim Thai government, Piyasvasti Amranand, announced in October 2006 that he did not intend to go forward with the agreements reached between

Beyond the fact that this commitment will continue to be contested by human rights groups, and recently formed the basis of a major protest by advocacy NGOs on 28 February, the policies being followed by the interim Thai government that has replaced the Thaksin regime are clearly less accommodating to

Navigating the

When River at risk was published in 2004, clearance of obstacles to navigation in the

Although the original plan for this first stage of the clearance operation envisaged obstacles being removed from the river as far as the Thai river port at Chiang Khong (and its Lao neighbour located directly across the Mekong, Huay Xai), unresolved boundary issues have meant that a final, major set of obstacles just upstream from Chiang Khong remain ― the boundary issues involved appear to relate to concerns on the part of Thai authorities that the removal of these obstacles might affect the thalweg, which is the national boundary between Thailand and Laos, as well as affecting the territorial status of sandbanks that regularly appear in the river during periods of low water. For the moment, with these obstacles still in place, Chiang Kong effectively functions as a terminal for Lao river vessels, but it is not accessible to large Chinese vessels that berth at Chiang Saen.

It also seems likely that no action has been taken to clear this remaining obstacle since there is a recognition that Chiang Khong will relatively soon become an important link in the road system that is being developed to run from Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province in China, to Bangkok. This highway will pass through

In terms of the parts played by the four parties to the 2000 navigation agreement since the clearances were completed, the roles of

In terms of the expansion of navigation on the

As recently as 2006, most Chinese vessels coming to Chiang Saen were still loading and unloading their cargo a little upstream of the town. They did this by mooring next to a section of the river’s bank that had been concreted for stability. There, with gangs of labourers employed to shift the cargo, it was carried over planks stretched between the boats and the shore. This very basic method of shifting cargo was apparently designed to circumvent paying port charges. This was despite the existence of port facilities constructed by the Thai authorities as long ago as 2004. These facilities are now in full use, as I witnessed them in January of this year. They consist of two covered pontoon docks equipped with conveyor belts and ramps suitable for truck traffic. At the time I observed the port in action, the pontoon docks were servicing eight vessels. Despite the presence of the conveyor belts linked to each dock, much of the cargo handling was still being carried out by labour gangs, with the bulk of the cargo being unloaded from

Some heavier goods were being loaded on to trucks on the docks and trucks were also being used to bring Thai palm oil and sacks of soybean meal as backloading of the Chinese vessels for their return trip. A mobile crane was also in use for even heavier items than those picked up or delivered by truck. In the light of the current activity around this existing port, there are plans to build a further facility downstream from Chiang Saen, which will be capable of servicing vessels up to 500 DWT.[29] Although some of my informants spoke of work already being under way for this new port, with feasibility studies supposed to have been completed by 2006, I did not see any indication of this during my visit to Chiang Saen. (See Photograph 2 of Chinese vessels moored at the existing Chiang Saen facilities in January 2007.)

Photograph 2: Chinese vessels at Chiang Saen

As a reflection of the Chinese dominance in this river trade, when I was in Chiang Saen, there were no fewer than 24 Chinese vessels in port and strung out over a distance of some kilometres along the river. This was in contrast to the three Lao vessels I observed, and the total absence of Thai vessels. Anecdotal accounts from Thai informants to whom I spoke in both Chiang Saen and Chiang Khong suggest that the imbalance between Chinese and Thai vessels travelling on the river is of the order of 90% to 10%. In general, Thai vessels are smaller and less powerful than their Chinese counterparts; this fact was the cause for some controversy and resentment during the 2003-04 dry season, when the

There are no reliable statistics for the number of Chinese vessels using the port on an annual basis, though it is certain that the figure of 3,000 vessels claimed for 2004 — an increase from 1,000 the year before — has most certainly been exceeded. As for the figures for the trade that passes through Chiang Saen, unofficial figures compiled by researchers for the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation, in Chiang Mai, for 2006, show a balance heavily in Thai favour, with imports from

In March 2006 a little-publicised agreement was signed by

Of considerable interest is the impact that the Mekong River trade is having on Chiang Saen town, and more generally within Chiang Rai province, within which the town is located. Until the early 1980s Chiang Saen, which I visited several times during that decade, was little more than an overgrown village beside the

Chinese immigration into

One reason this is so is the quite clear indication that illegal and undocumented Chinese immigration into

As already noted in relation to the shipments of oil up the

Concluding Remarks

The developments discussed in this paper point to the manner in which environmental issues, and frequently those issues combined with concerns relating to human rights, are playing an increasingly important part in the politics of the Asian region. Concern for the environment is no longer a fringe issue, and there is no more striking illustration of this fact than the domestic opposition that was mounted within China to the proposed dams on the Nu, and which sparked the important but unexpected reaction by the Chinese premier, Wen Jiabao, to step in and put plans for the construction of 13 dams on hold. Attention has also been drawn in the paper to the important part played by Thai environmental activists in relation to their government’s policies, both towards the

Although the broader issue of climate change has dominated global discussion of environmental issues, the politics of water, of its use and its availability are receiving ever-greater attention. And this is likely to be increasingly the case as the future use of rivers in

Neither the Salween nor the Mekong are close to the parlous state of China’s Yellow River, which is suffering from the combined effects of overuse, recurrent droughts, and the decrease of snow-melt as Himalayan glaciers contract in size. The river’s dire condition has prompted consideration within

At another level, the issues examined in this paper reinforce the judgments made in The paramount power, as

APPENDIX

A brief overview of current, and controversial, issues associated with the Mekong

The content of this paper has, in relation to the

The first of these two documents has been released at a time when there is very active discussion about the future role of the MRC, in particular the extent to which it can play a role in which its trans-national responsibilities can supersede the interests of its four, individual national members.[36] And, most importantly, it bears on the question of the extent to which the MRC should play a role in promoting development (infrastructure such as dams and water diversion projects) as opposed to its role to date as, essentially, being a repository of knowledge about the Mekong River and its basin.[37] The particular salience of this latter issue is illustrated by the fact that the MRC document discusses in detail a range of predicted and costly effects that could occur in Cambodia — where fish form the overwhelming source of the population’s protein intake — in the event of three different ‘flow regimes’.[38]

The WB/ADB Working Paper, which, most usefully, should be read in conjunction with the MRC paper just discussed, states in its ‘Executive Summary’ that the ‘bottom line message of this Mekong Water Resources Assistance Strategy is that the analytical work on development scenarios has, for the first time, provided evidence that there remains considerable potential for development of Mekong water resources’. In the light of this conclusion, and conceived in terms of the river’s trans-national character, the paper urges a move away from ‘the more precautionary approach of the past decade that tended to avoid any risk associated development, at the expense of stifling investments’. While not disregarding risks, the paper argues that ‘balanced development’ should be ‘the driving principle for the management and development of the Mekong River Water resources in the coming years’.[39]

The issues involved in these two documents go the heart of the

As discussed in River at risk,

This article was originally published at Lowy Institute for International Policy, Ausutralian National University, May 2007. Posted at Japan Focus, June 11, 2007.

Milton Osborne is an Australian historian, author, and consultant specializing in Southeast Asia.

[1] World’s top 10 rivers at risk,

[2] River at risk: the Mekong and the water politics of China and Southeast Asia, Lowy Institute Paper 02, The Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, 2004; and, The paramount power: China and the countries of Southeast Asia, Lowy Institute Paper 11, The Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney, 2006.

[3]

[4] Jim Yardley, Chinese Premier focuses on pollution and the poor, New York Times,

[5] See Osborne, River at risk, pp 31-2, in relation to the Pak Mun dam and the subsequent policy shift by the Thai government.

[6] UNESCO World Heritage, Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas.

[7] Background information on the Salween is usefully provided in, The Salween under threat: damming the longest free river in Southeast Asia, published by Salween Watch, Southeast Asia Rivers Network (SEARIN), and the Center for Social Development Studies, Chulalongkorn University, Chiang Mai, 2004. Although quite clearly an advocacy document, there is no reason to question the basic facts provided in it.

[8] Jim Yardley, Chinese project on the

[9] For details of the ASEAN Power Grid, see here.

[10] Yardley, as cited in footnote 6.

[11]

[12] Osborne, River at risk, pp 12-13, and footnote 17.

[14]

[15] Executive Summary, Report of a Joint Reactive Monitoring Mission to the Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas, China, from 5 to 15 April 2006, pp 2-3.

[16] UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, World Heritage Committee, Thirtieth Session, Vilnius, Lithuania, Asia-Pacific, 8-16 July 2006, pp 5-6.

[17] Ibid, footnote 15.

[18] UNESCO, Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, World Heritage Committee, Thirtieth Session, Vilnius, Lithuania, 8-16 July 2006, Asia Pacific, pp 7-8.

[19] Zhang Kejia, Three Parallel Rivers region focus on monitoring mission.

[20] These developments are summarised in Will Baxter, Dam the

[21] Interview with Khun Kraisak Choonhavan,

[22]

[23] Shawn L. Nance, Unplugging Thailand,

[24] Will Baxter, Dam the

[25] Will

[26] This and the immediately succeeding paragraph draw directly on River at risk, pp 25-9.

[27] The Nation, (

[28] I visited Chiang Saen and Chiang Khong, most recently, over the period 15-17 January 2007. I first visited this region in 1979 and have continued to visit it on an irregular basis since that time.

[29] Jason Gagliardi,

[30] See, River at risk, pp 19-20.

[31] Vaudine

[32] On the oil shipment, see, Marwaan Macan-Markar,

[33] Joshua Kurlantzick,

[34] Jason Gagliardi,

[35] Montree Chantawong, The Mekong’s changing currency, Watershed: People’s Forum on Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 2, November 2005 – June 2006, pp 12-25.

[36] Philip Hirsch, Kurt Morch Jensen, with Ben Boer, Naomi Carrard, Stephen FitzGerald and Rosemary Lyster, Executive Summary, National interests and transboundary water governance in the

[37] For some very recent discussion of this issue, see, Richard P. Cronin, Destructive Mekong dams: critical need for transparency,’ RSIS Commentaries, a publication of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Singapore,

[38] Mekong River Commission, Water Utilisation Program, Integrated Basin Flow Management Report No.8, Flow-regime assessment, Draft 1 February 2006, p 57.

[39] WB/ADB Joint Working Paper on ‘Future directions for water resources management in the

[40] River at risk, pp 32-4.

[41] For recent discussion of the Vietnamese dams, see, Montree Chantawong, as cited in footnote 35, and, Sam Rith and Cat Barton, Vietnamese dams proposed for Cambodian river, Phnom Penh Post, 21 September-