Writing Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the 21st Century: A New Generation of Historical Manga

Michele Mason

This article addresses the struggles of two manga artists, Kōno Fumiyo and Nishioka Yuka, who attempt to portray the unprecedented tragedies of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for a contemporary audience, and how they come to terms with their authority to write this history as non-hibakusha.

While historical comics (manga) have generally not captured the popular imagination in the United States, they regularly rate among the top bestsellers of the medium in Japan. Examples range from the mostly fictionalized “chanbara” works that glorify samurai swordsmen to narratives featuring prominent historical figures, such as Miyamoto Musashi, Caesar, and Gautama Buddha, as written by Tezuka Osamu in his biography Buddha (1972-83). While the era of the samurai remains a particular favorite, other historical moments have also provided rich source materials for this genre of graphic novels. For example, Tezuka’s work, Shumari (Shumari, 1974-76), set in Meiji era (1868-1912) Hokkaido and Gomikawa Junpei and Abe Kenji’s The Human Condition (Ningen no jōken, 1971), which treats Japanese imperialism during the Asia-Pacific War (1931-1945).

Some historical manga go beyond simple entertainment and take explicit pedagogical or propagandistic aims. There is, for instance, Ishimori Shōtarō’s monumental A Comic Book History of Japan (Manga nihon no rekishi, 1997-99), whose fifty-five volumes cover over a millennium of Japanese history. In the vein of tackling overlooked and controversial subjects are Sato Shugā’s two critical volumes on the history of the emperor system (Nihonjin to tennō, 2000 and Tennōsei wo shiru tame no kingen daishi nyūmon, 2003), Higa Susumu’s Kajimunugatai (2003), depicting the Battle of Okinawa, and more recently the collectively produced Ampo Struggle (Ampo tōsō, 2008). Yamano Sharin’s Manga: Hating the Korean Wave (Manga: kenkanryū) is just one example of the growing number of revisionist and nationalistic histories. In The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History, Tessa Morris-Suzuki states, “…comic book versions of history – whether fictional or non-fictional – have probably shaped popular understandings of history at least as much as any textbook.”1 With their compelling combination of visuals and text, historical manga clearly represent a powerful means for constructing modern notions of the past and shaping national collective memories.

Recently, two Japanese manga artists have tried their hand at writing about one of Japan’s most significant historical events, namely the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The bestselling and award-winning Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms (Yūnagi no machi sakura no kuni)2 by Kōno Fumiyo first appeared in 2003, with a live-action film version debuting in 2007. In 2008, Nishioka Yuka published A Summer’s Afterimage: Nagasaki – August 9 (Natsu no zanzō: Nagasaki no hachigatsu kokonoka).3 Both feature prominent female protagonists and inter-generational narratives that address such topics as discrimination against hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors),4 living in post-A-bomb poverty, the plight of Korean survivors, and the uncomfortable implications of both the denial of Japanese aggression in Asia and the American myth that continues to justify the bombings.

Both Kōno and Nishioka, who grew up in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, have commented on their struggles over how to portray these unprecedented tragedies and how to come to terms with their authority to write this history as non-hibakusha. Committing to their projects more than sixty years after the events, these two manga artists negotiate difficult ethical terrain. Motivated to reach a new audience that knows little of the truth of this period of history, Kōno and Nishioka grapple with balancing the need to create stories that will capture readers’ attention and the imperative to maintain ethical limits of representation that respect both survivors and the dead.

In this article, I elucidate how narrative structure and perspective in Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms and A Summer’s Afterimage: Nagasaki – August 9 are linked to their creators’ position in history. Namely, Kōno’s and Nishioka’s narratives creatively interweave stories of the past and present viewed from the vantage point of the children and grandchildren of survivors, prioritizing the long aftermath over the immediate effects of the bombings. This choice is also manifested in the scant number of frames “recreating” August 6 and 9. The “point of view,” anchored in the central characters, might more appropriately be characterized, especially in the case of A Summer’s Afterimage, as the “point of listening.” Ultimately, Kōno’s and Nishioka’s narrative strategies ensure that these works are not just a “re-telling” of these two historical events, but make crucial connections to their relevance to global citizens living in the 21st century.

Non-Hibakusha Writers and the Ethics of Representation

The thorny issues related to the representation of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – for instance, the inability of language to fully convey the reality of survivors’ experiences and the significant chasm between the victim-writers’ experiences and the non-victim readers’ ability to “understand” them – have sparked debate among and presented challenges to the hibakusha community. In his invaluable work, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb, John Whittier Treat remarks that the belief on the part of some survivors that their experiences are “unspeakable” and inaccessible to outsiders, poses a “considerable technical and even ethical hurdle”5 to the writing process. Moreover, in confronting the decision to write or remain silent, survivors feel a justified apprehension towards the “stylization” of language necessitated when committing one’s experiences to paper, fearing outsiders may dismiss the truth of their “unimaginable” narratives as “fiction,” or, equally troubling, as “too real.”6 As Treat notes, even the most capable stand frozen in the face of the task. “Hibakusha who were or become professional writers, and who thus might be thought to have the talent to make the ‘incredible’ available to us, …confess an emotional surplus that paradoxically paralyzed the expression of those emotions and that made ordinary communication impossible.”7

Still, hibakusha have taken up the pen for a great many reasons. Some seek to comprehend their experiences or attend to grief by addressing the trauma. Some feel compelled to document the pain and losses for themselves and others. Recording their testimonies and personal experiences is sometimes understood as a moral imperative to challenge those who write history in such a way that justifies the use of atomic weapons. Due to the perseverance of many writers, professional and otherwise, a vast and varied collection of prose, poetry, and drama now constitutes a genre in and of itself known as “atomic-bomb literature” (genbaku bungaku).

The non-hibakusha who attempts to depict such a disturbing and monumental event confronts a different, yet sufficiently challenging, set of problems. Her preparation begins not only in the factual historical research – which may be emotionally challenging enough in and of itself to forestall the project – but also the task of framing her legitimacy to write on the subject. If one considers Hiroshima writer Fumizawa Takaichi’s statement, “It was a primal event that denies all but other hibakusha its vicarious experience,”8 or hibakusha poet Hara Tamiki’s question of “whether the meaning of the atomic bomb could be grasped by anyone whose own skin had not been seared by it,”9 it is only natural that a non-victim should pause and even doubt the feasibility of writing on the subject.

In the essay “The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” Anna Richardson, examines contentious debates on representing the Holocaust, tracing tensions between arguments for keeping silent and speaking out, testimony and fictionalization, survivor and non-survivor writing and ethics and aesthetics.10 In weighing the argument that the writing of fictional narratives of the Holocaust by non-victims can be disrespectful to survivors, Richardson quotes Imre Kertesz, who writes, “the survivors watch helplessly as their only real possessions are done away with: authentic experiences.”11 As numerous scandals over fake memoirs in recent years suggest, there is a moral prohibition against falsely claiming legitimacy to write traumatic memory.12 The tacit bond of trust between the writer and reader is paramount, and Richardson cautions that representations of extreme horrors by those who are not victims “…runs the risk of negating similar excesses of violence represented in actual testimony, and, in the worst case scenario, opening the door for Holocaust deniers to claim that other accounts are equally fictitious.”13 While cognizant of the charged nature of representation, Richardson makes a case for the benefits of Holocaust fiction, by both survivors and non-survivors, suggesting it is not a question of whether but how one represents these events.14 She points out that fictionalizations may have the advantage of being “more accessible than a survivor memoir,”15 have important pedagogical value, and, above all, ensure that the Holocaust is not forgotten.

New generations of writers, in fact, continue to address the Holocaust in a variety of media. The Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus by Art Spiegelman, son of two Holocaust survivors, is arguably the most famous and courageous historical graphic novel from the United States. This groundbreaking work that portrays its ethnic/national characters through anthropomorphic animals – Jews as mice, Poles as pigs, and Nazis as cats – explicitly illustrates the struggle of the second-generation in its self-referential mode. In Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, II: And Here My Troubles Began, the author depicts his own struggle to engage with and portray the unfathomable horror of his topic. Speaking to his therapist, he bemoans, “My book? Hah! What book?? Some part of me doesn’t want to draw or think about Auschwitz. I can’t visualize it clearly, and I can’t BEGIN to imagine what it felt like.”16 Addressing Holocaust fiction, Sara Horowitz states, “Because second-generation writers lack… validation in the personal history of the aesthetic project, they must struggle to define artistic parameters to represent Auschwitz in the ways that avoid the pornographic, the voyeuristic, the sensational, or the sentimental.”17 In the cases of the Holocaust and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki there is a reasonable “discomfort with the idea of an aesthetic project built on an actual atrocity”18 with which both writers and readers must engage directly.

As for atomic-bomb literature, we are certainly provoked by Ota Yōko’s City of Corpses, stunned by Tōge Sankichi’s graphic poems, and touched by Hara Tamiki’s short stories. We have little trouble believing the veracity of their “testimony” even in these survivors’ “fictional” and “literary” works. Still, we are likewise moved by the “storytelling” of Ibuse Masuji, who is not a hibakusha. His Black Rain remains one of the most famous works of this genre that continues to pass on larger truths of the atomic bombings.19 At the same time that we respect the authority that comes with being a survivor, we can recognize the merits of works by those who are committed to an ethical rendering of such tragic events (whether it be Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or the Shoah) by those who possess no direct experience.

Second generation hibakusha or children of Holocaust survivors are often particularly aware of their families’ histories, sometimes through oral stories and sometimes by the palpable absence of them. Discussing artistic works of second-generation Holocaust survivors, Stephen C. Feinstein writes, “This is an event they did not live through, yet the event, or the memory of the event, has a compelling presence.”20 In their secondary materials, Kōno and Nishioka, ever cognizant of their native cities’ tragic histories, express sentiments similar to those of fellow comic-book-artist Spiegleman – apprehension, doubt, hesitancy – as they articulate their motivations and honestly record their complicated engagement with the painful subject of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Kōno and Nishioka’s Narrative Strategies

Among historical manga, Nakazawa Keiji’s Barefoot Gen (Hadashi no Gen, serialized from 1973-1985 in Weekly Shōnen Jump), stands out as something akin to a “manga memoir,”21 based as it is on the author’s personal experience as a survivor of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. After his mother’s death in the late 1960s, Nakazawa began writing on the atomic bombing in his “Black” and “Peace” series, but it was not until his editor urged him to write about his own experiences that he penned “I Saw It” (Ore wa mita), which he expanded to make what would eventually become the ten volumes of Barefoot Gen.22

In Barefoot Gen, readers get to know third-grader Gen (Nakazawa) and his family beginning in April 1945, “witness” the catastrophe on August 6, and then take in the frightful scenes and confusion of the immediate aftermath. Unable to rescue three of his family members, Gen attempts to carve out a precarious existence in the atomic wasteland with his mother and infant sister, who is born prematurely on the day of the bombing. Framed through Gen’s experiences, the narrative portrays emotional reunions and deaths, ordeals of privation and discrimination, and the harsh realities of life during the occupation years. Nakazawa deftly weaves light-hearted humor, centered on the antics of young Gen and his “brothers” and friends, in this compelling depiction of both the horrors of the nuclear attack on Hiroshima and the struggles of hibakusha in the early postwar period. It might be said that such a juxtaposition of playful and painful scenes is the prerogative of a survivor like Nakazawa, who speaks of being haunted by “the stench of corpses” when he conjures up his many disturbing memories to write on Hiroshima.23

For writers like Kōno and Nishioka, who are not survivors or descendents of survivors, the questions related to writing on the atomic bombings are inflected in a decidedly different way. Although Kōno and Nishioka state clearly that their works are not based on personal experience, they still tremble in front of their projects and search for a narrative mode that will allow them to use their voices and create their visions. Both speak to how deeply affecting it is to listen to hibakusha testimonies, view photographic images and artistic renditions, read personal stories, and imagine the events in the course of preparatory research. They acknowledge the impossibility of “understanding” the experience of being an atomic bomb victim and never claim a legitimacy that is not rightfully their own.

Kōno was first encouraged to write on “Hiroshima” by her editor. Mistaking her editor’s meaning at first, Kōno delighted in creating a story set in Hiroshima and being able to use the local dialect freely. When it finally occurred to her that he was talking about “the Hiroshima,” she was immediately overcome by doubts. She recalled nearly fainting more than once when faced with disturbing artifacts at the Hiroshima Peace memorial or viewing historical footage of the aftermath of the bomb. She admits having convinced herself that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima was “a tragedy that occurred in the distant past” and that she had “tried to avoid anything related to the bomb.”24 However, when Kōno realized that many people outside of Hiroshima and Nagasaki knew little or nothing about the bombings, she felt it “unnatural and irresponsible to remain disconnected from the issue.”25 “This was no time to hold back. I hadn’t experienced war or the bomb firsthand, but I could still draw on the words of a different time and place to reflect on peace and express my thoughts.”26 While initially hesitant, Kōno finds that her past experience in drawing manga gave her “courage” to take on a story that was not her own. After all, she decided, “drawing something is better than drawing nothing at all.”27

Nishioka, as well, found her decision to produce A Summer’s Afterimage accompanied by uncertainty and misgivings. A native of Nagasaki, Nishioka grew up thinking she would like to some day write on the city’s tragic history. However, she recalls, “… as I turned the pages of collections of survivors’ testimonies, my fingers would simply freeze. How can one convey the cries of people thrown into this hell and stench of death, which are ‘beyond imagination’ and ‘impossible to express with words’?”28 It was a seemingly unconnected international incident, Israel’s bombing of the Lebanese city of Qanaa on July 30, 2006, that pushed her hand.

Several days later, Japanese people who had been pained by the bombing gathered together, and a man, who was an atomic bomb survivor took the microphone and made an appeal, saying, “Soon it will be August 9. People like me who have experienced the tragedy of atomic bombs, cannot allow another war in which innocent children are killed in this way.” This gave me a shock. The war-torn city [of Qanaa] and Nagasaki were connected through suffering.29

In linking Qanaa and Nagasaki, Nishioka realizes that she could write from an outside perspective, which allows her to create Kana, her female protagonist named after the city in Lebanon.30 Even after this insight, however, Nishioka’s malaise continued. To make it possible for her to take on the project she visited the monument that marks the epicenter in Nagasaki, prayed to the many victims of the atomic bombing, and asked for permission to create her manga. With the same tenuousness displayed in Kōno’s phrase “It was better to draw something rather than draw nothing at all,” Nishioka laments. “I was only able to merely skim the surface of the atomic bombing.”31

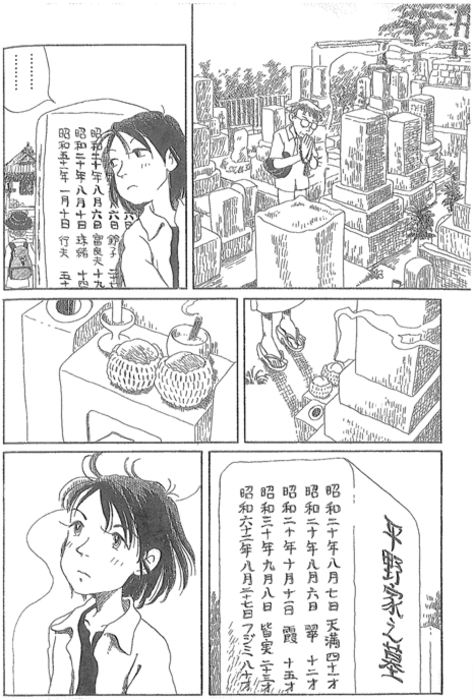

Kōno and Nishioka take pains not to present their work as autobiographical. To address this overwhelming concern, both artists center most or all of their narratives around a descendent, daughter or granddaughter of survivors. Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms interweaves stories that move between the 1950s and 2005. The first narrative, Town of Evening Calm, portrays the lives of survivors Hirano Minami and her mother, Fujimi, as they cope with privations in the “atomic slum” (genbaku suramu) of Hiroshima,32 long-term illness related to radiation poisoning, and the loss of three family members. Yet this constitutes just one-third of Kōno’s text. Country of Cherry Blossoms, begins in the late 1980s, focusing on fifth-grader Nanami, the daughter of Asahi Ishikawa, Minami’s brother who was not in Hiroshima in August 1945. Nanami’s deceased mother was a hibakusha. Much of Nanami’s life is shaped by visits to a hospital where her grandmother (Fujimi) and younger brother Nagio are treated regularly for chronic illnesses. Part Two, set in 2005, finds Nanami on a mission to discover the reasons behind her father’s recent odd behavior and disappearances. When she and an old friend follow him, they discover that, occasioned by the 50th anniversary of his sister Minami’s death, Mr. Ishikawa had been traveling to Hiroshima to hear stories about her from people who knew and loved her.

Nanami follows father to family grave in Hiroshima. Kōno Fumiyo, 2004. Courtesy of Futabasha Publishing.

Through flashbacks and subplots, Kōno fleshes out the story of how Nanami’s parents met and grew to love each other, Nanami’s mother’s death, and discrimination against both first- and second-generation hibakusha as marriage partners.33

The main character and our portal to memories in Nishioka Yuka’s ambitious work, A Summer’s Afterimage, is Kimura Kana whose grandparents survived the Nagasaki atomic bombing. This work grapples with not only the painful memories and trauma of Japanese survivors, but also the discrimination Korean hibakusha faced, the legacy of Japan’s colonial past, the American “atomic myth,” and questions of the morality of science. One of just a few works that focuses on Nagasaki,34 A Summer’s Afterimage follows protagonist Kana through five vignettes, in which she hears the testimonies of Japanese and Korean hibakusha and other persons who share their wartime experiences as she travels to Nagasaki, the United States, and Korea.

Kōno and Nishioka reinforce their historical positionality by directing the transmission of memories from survivors of the war and atomic bombings to contemporary characters and readers.35 In much the same way that their manga pass on the history of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to a new generation, the elders in their texts share their “authentic memories,” bequeathing them to younger individuals. In Country of Cherry Blossoms, Nanami’s father, Asahi, who was sent to live with relatives in Mito during the war, travels to Hiroshima to hear (and collect) stories about his beloved sister so that he can properly commemorate her death. Pushing the limits of memory is the touching and humorous scene wherein Asahi asks Kyoka to marry him. This “memory” in fact comes to us in a “flashback” by their daughter, Nanami. She muses: “Perhaps I’d heard these stories from my mother. Somehow, I remember these scenes. From before I was born…I was watching them. I looked down at those two and decided to be born to them. I am sure of it.”36 Kōno suggests that when we listen to history – to the stories of those who lived history – it can become our memory. In this way she moves away from the idea of proprietary memory towards one of shared memory across generations.

Notably, Nishioka’s narratives emphasize active listening and the recognition of historical “others” as she ponders the potential of healing personal pain, families, and nations. The five vignettes in A Summer’s Afterimage maintain the complexity of people’s differing experiences (from person to person and across nationalities) and highlight the importance of acknowledging the suffering of others who were once an “enemy.” The section “Manhattan Sunset,” follows Kana and her grandmother, who travel to New Mexico to attend an exhibit, which features a film-clip of Kana’s grandmother soon after the dropping of the bomb. When the grandmother takes ill, Dr. Smith, provides medical assistance and shares a narrative of his childhood in Los Alamos where his father worked with Dr. Oppenheimer to produce the world’s first three atomic bombs.

Dr. Smith as a child at Los Alamos. Nishoka Yuka, 2008. Courtesy of Gaifū Publishing Inc.

A trip to the Trinity Test Site reveals Dr. Smith’s conflicted feelings, but ultimately he cannot let go of the idea that the bomb was necessary.37

The last episode, “Asian River,” concentrates on Kana’s visit to Korea, where she is guided by the grandson, Soyon, of a Korean hibakusha, Mrs. Park, who was treated by Dr. Kimura, Kana’s grandfather, in Nagasaki after the bombing. Kana listens to Mrs. Park’s moving story and visits the demilitarized zone (DMZ), “the Berlin Wall of Asia.” Her short trip turns out to be an important lesson for Kana on the history of Japanese colonialism, the discrimination against Koreans after the atomic bombing, and the legacy of the Korean War.

Mrs. Park faces discrimination in immediate aftermath of the bombing. Nishioka Yuka, 2008. Courtesy of Gaifū Publishing Inc.

On August 15, the day Koreans celebrate liberation from their Japanese oppressors, Kana and Soyon build and launch a “spirit boat” that they name “Asia” for all who passed away in the war.

Kana and Soyon launch a “spirit boat” in the name of all who perished in the Asia-Pacific war. Nishioka Yuka, 2008. Courtesy of Gaifū Publishing Inc.

“The Portrait,” finds Kana and her grandmother getting ready for anniversary services on August 9 when they run into a German who shares his story of returning from the war to find nothing more of his wife, a painter, than her self-portrait. He has come to Nagasaki to pay his respects believing that it could just as well have been Germany that the U.S. bombed with the new weapon. Together the three remember the dead and pray for their repose.

In their plot lines and textual organization, both Kōno and Nishioka create room for collective memories grounded in the inter-generational transmission of “stories.” For most of Kōno and Nishioka’s texts both characters and readers are firmly located in our current historical moment, occasionally traveling back in time via survivors’ testimonies and memories. In a variety of ways, they attempt to link the summer of 1945 to the contemporary moment, pointing to the lingering social and political ramifications of history that can otherwise seem distant and cut off from the present.38 Nishioka’s brief epilogue, in which Kana joins other high school students collecting signatures for a petition calling for nuclear abolition, goes one step further in urging members of a new generation to seek their own place in this ongoing history.

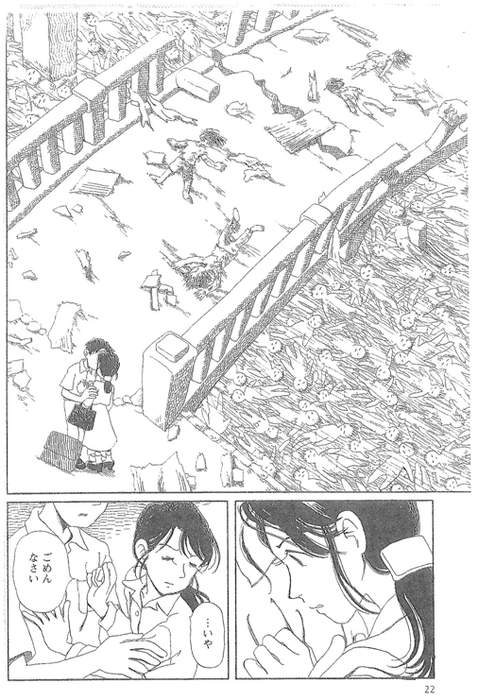

Given that Kōno and Nishioka’s works are undoubtedly about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the dearth of scenes depicting August 6 or 9 is striking. Both eschew drawing scenes that attempt to “recreate” the period immediately after the atomic attacks. Whereas readers of Nakazawa’s Barefoot Gen join Gen and his family in August 1945 and “witness” the pika-don moment (the initial flash and blast), for most of Kōno’s and Nishioka’s texts, both characters and readers are firmly located in our current historical moment, occasionally traveling back in time via survivors’ testimonies and memories. Just three frames in all ninety-eight pages that comprise Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms depict the immediate aftermath of the bombing. In these Kōno usually keeps the character Minami in her body and clothing of 1955 – a mingling of the present and the past. In one frame, the heavily penned hair, shoes, and bags of Minami and her suitor first draw the reader’s eye to the lower left corner. Then we notice the mass of indistinguishable bodies floating in the river under a cracked bridge strewn with debris.

Minami struggles with her disturbing memories. Kōno Fumiyo, 2004. Courtesy of Futabasha Publishing.

In another frame, the Minami of 1955 runs past a group of children’s vacant faces, as she relives those initial moments of panic, while one scene shows the postwar Minami following behind her sister Kasumi and walking amongst the dead bodies and detritus.

Only eight pages in A Summer’s Afterimage, a work numbering 132 pages, feature scenes of the initial moments of the bombing – for instance, a flash and a mail carrier blasted into the air. In one episode, we see a pile of skulls and bones and a woman screaming in tattered clothing. Still, even though some disturbing images are included, many of the visuals are one step removed. In one case, we see only the faint details of four photographs that are part of the exhibit in Los Alamos. In one episode, a highly stylized version of the mushroom cloud symbolizes the Nagasaki bombing.

There are no attempts to overwhelm our senses with the violence of the atomic bomb. Rather the manga artists choose to portray the quieter suffering of hibakusha and their loved ones. In Town of Evening Calm this is revealed through the character Minami who survives ten years only to find that she too will join the ranks of dead victims. Her last thoughts are, “This isn’t fair. I thought I was one of the survivors.”39 Nanami and her brother Nagio in Country of Cherry Blossoms represent the “second generation” of survivors who endure (atomic related) diseases and the silent pain of older relatives who continue to grieve for family members lost to the bombings. Depictions of the mundane details of survival are prioritized over visuals of the flash, blast, or heat that a rare and simple line of text informs us seared a barrette into Minami’s hair and melted the soles of her shoes.

If these two historical manga focus on the living more than the dead, it is not because the authors have forgotten them. One critic of John Hersey’s 1947 Hiroshima made the provocative observation that “The living occupy all the foreground, and the mounds of dead are only seen vaguely in the background,”40 while another claimed, “To have done the atom bomb justice, Mr. Hersey would have had to interview the dead.”41 Richardson maintains that this is precisely the task that fictional works can perform; “… a work of fiction has the power to take the narrative to places that survivor testimony cannot,”42 namely to let the dead speak. Hibakusha have made similar claims, such as when Numata Suzuko states “… that as a survivor who was ‘made to live among thousands of those who fell victim to the bomb,’ she feels a need to ‘embrace the voiceless voices of the dead – so that they do not have to feel they died in vain.”43 Nishioka’s words echo this idea in her commentary on the episode called “The Last Letter.”

There is a model for the character who is a postal carrier. I finally realized something upon hearing this person’s testimony given after the bombing, when he told me in a lively fashion about the beautiful townscape and the lives of the people before the bomb when he was going about delivering mail on his red bicycle. Until “that moment,” people were going about their modest daily lives just as we do today. When I faced the fact that before 1945 an atomic weapon had never been used in war, I came to understand how presumptuous I had been, and I felt compelled to say in front of the epicenter monument “All you who died, it was not in vain. Certainly, it was not in vain.44

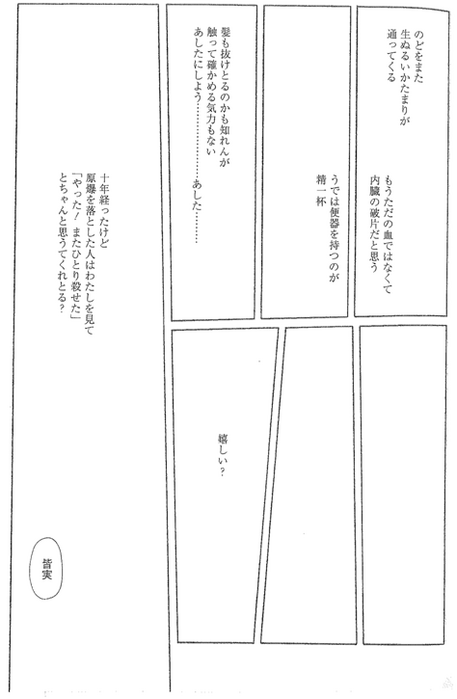

Nishioka also allows those who perished to have the last word in each of her stories. “All five stories collected here end with the words of the dead. In lending my ears to the voices of the afterimages and bringing them back to life today, I want to offer the only tribute to them that I can.”45 The moving words of characters or, in the case of the episode “Manhattan Sunset,” the lines of a poem by the Nagasaki survivor and poet Fukuda Sumako, resonate as they bring each chapter to an end.46 Even more directly Kōno depicts Minami’s last moments in Town of Evening Calm. Pictures of Minami on her deathbed are interspersed with completely blank frames that convey the heaviness of death better than any number of strokes Kōno’s pen could have. Eventually all renderings of Minami’s body give way to images of faces hovering over her, placing us in her viewpoint. Readers are privy to her thoughts, which are printed in otherwise empty frames. In one instance there is the single word “pain” and in another we “hear” Minami thinking, “It’s been ten years. I wonder if the people who dropped the bomb are pleased with themselves – ‘Yes! Got another one.’”47

Empty frames contain Minami’s dying thoughts. Kōno Fumiyo, 2004. Courtesy of Futabasha Publishing.

As many similarities as these two works share, it is imperative to note several significant differences. Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms concentrates on the memories of Hiroshima hibakusha and specifically the personal experiences of members of the Hirano/Ishikawa family. Although emotionally powerful, Kōno’s work focuses its “humanist” lens narrowly on Hiroshima, failing even to make the obvious connection with Nagasaki. One of the two references to a wider conversation on nuclear issues is a large sign announcing the 1955 World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (gensuibaku kinshi sekai taikai) that Minami passes in the street on her way home from work. The other is a tattered flyer version of the sign, imprinted with the phrase “the power of peace for Hiroshima,” which flutters in the air and falls to the ground in the frames immediately preceding Minami’s death. This ending of the first story begs the question of whether the text aims to equate the futility of fighting radiation sickness to the peace movement’s struggle against nuclear proliferation.

Nishioka’s A Summer’s Afterimage on the other hand, takes a much broader perspective, including the memories of Germans, Americans, and Koreans and addressing a wide range of issues. Although its discursive format may be considered a weakness, it maintains the complexity of history as it addresses the history of Japanese colonialism, recognizes the humanity of those who justify the U.S. decision to drop the atomic bombs, and poses uneasy questions regarding science and technology. If the ending of Town of Evening Calm suggests a dim prospect for “peace in Hiroshima,” Nishioka’s work concludes on an optimistic and outward-looking note as Kana joins a group of youth bearing a banner that calls for global nuclear abolition.

Their differing framing of and commitment to broader issues can be seen in other ways as well. It is notable that reviews of Kōno’s work routinely remark that the antiwar stance is subtle. Otaku USA writes that the “anti-war message is unspoken, and comes naturally from the desire not to see the characters die,”48 and Manga: The Complete Guide salutes its “understated antiwar statement.”49 Kōno’s biography on the backflap is devoted completely to her impressive training and accomplishments as a manga artist, and she does not seem to have thought about producing a work about the subject until her editor suggested the project. Nishioka’s author profile, however, makes explicit her engagement with the peace movement, such as her circumnavigation of the globe on the Peace Boat, her participation in the Hague Peace Conference, and her volunteer work in a Palestinian refugee camp. She also writes, as stated above, that she had long hoped to create a manga on the atomic bombing of Nagasaki.

These differences are not, however, merely manifestations of personal inclinations. They also reflect distinctions between the way the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Kōno and Nishioka’s respective hometowns, reflect on their atomic legacy and engage with its significance today. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, even in its updated version, centers on Hiroshima, giving scant attention to the larger question of nuclear issues, even the atomic bombing of Nagasaki. The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, on the other hand, goes well beyond the summer of 1945 and the boundaries of its city. Visitors do not leave the building without passing through a hall whose exhibits present the scope of contemporary proliferation and make crucial connections with world-wide environmental degradation and human suffering connected to nuclear testing (Marshall Islanders, downwinders in the United States) and nuclear power plant accidents (Three Mile Island, Chernobyl) and more.

Still, both Kōno and Nishioka clearly see their aim to be, in large part, educational. Because they conceive of their audience as a younger generation who knows little of the facts or truth of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they include maps, historical information, and bibliographic references for further reading. Kōno’s supplementary materials, for example, provide contextualization of what were called the “atomic slums” in Hiroshima and the history of the preservation of the Atomic Dome. Nishioka appends a short essay to explain the events upon which each chapter is based and briefly provides factual details of the Nagasaki bombing, discusses problematic tenets of the American “atomic myth,” and introduces youth participation in post-war nuclear abolition movements. In order to speak of the past and of the dead to the living, Kōno and Nishioka build on their organic “education” from growing up in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In these two manga, they bequeath critical historical truths in a medium that has the power to reach younger people in the narrative and visual language of their generation.

Conclusion

Different historical periods, events and personages permit different degrees of license to fictionalize. Writing on singular, unprecedented events such as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki raises particular issues for both survivors and later generations. For survivors there are numerous challenges, not least of which is reliving the traumatic memories in the writing process. How to overcome the inadequacy of language to depict the truth of their experiences and the fear that non-survivors might too readily assume they can “understand” the trauma are also common concerns. For later generations the issues revolve around questions of authorial authenticity, literary license, historical imagination, and truthfulness. Kōno and Nishioka are the first non-victims to marshal the popular medium of manga and produce nuanced full-volume treatments of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite their temporal and experiential distance from the events and the fact that some may consider their works “non-literary,” I believe we need not hesitate to add their works to the impressive body of atomic-bomb literature. In their organization, themes, and tone, these two works are distinct. Yet, both writers creatively engage a weighty subject, and in doing so they eschew any hint of a memoir, instead aligning their narratives’ temporality with a new generation of readers who also find themselves far removed in time from the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Both Kōno and Nishioka speak to the psychic and conceptual hurdles that had to be overcome to undertake their projects. That Kōno and Nishioka detail their conflicted feelings about their subject seems a necessary part of ethically representing Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ever careful of the bond of trust between writer and reader, Kōno and Nishioka take great pains to position themselves as non-hibakusha, as well as to be faithful to the personal accounts inherited from those who experienced Hiroshima and Nagasaki firsthand. Through the depiction of people and experiences not so removed from our own lives and historical moment, they have effectively drawn characters and created stories to which their contemporaries can relate. I would guess that they would be sympathetic to German artist Lily Markiewicz’s statement:

Mine is an exploration of an aftermath, of a past which has become a present, of the absence of a traceable reality which has become the presence of memory. I am not concerned with the Holocaust directly, the event, its causes, reasons and details. I am concerned with the ripples, the ramifications, the consequences and our perceptions of it – our place ‘in it.’50

This idea is suggested in Nishioka’s title, A Summer’s Afterimage, which evokes the personal and collective memory that lingers long after the summer of 1945.

Representations of those fateful days in August that ruptured history and anointed the atomic age with flames and the stench of human flesh play a crucial role in keeping historical memory alive. Yet, it is equally important to think beyond that one month in 1945 to the years that stretched out before the “survivors” and contemplate the strength and courage needed to live on. Kōno and Nishioka offer a solemn and respectful tribute to both the dead victims and the hibakusha. Moreover, they give those of us who care to reflect on the relevance of past suffering to that of our world not just a reminder of historical events far removed from the present but two fictional manga that speak important and timely truths. Stephen Feinstein’s statement that “The art that memorializes the Holocaust may itself become the subject of memory, a memory of a memory, or memory within the complex remembrance of the Holocaust”51 seems particularly applicable to these two works. Kōno and Nishioka’s historical manga – two articulations of “memory” within the complex remembrance of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – offer powerful “afterimages” that can inform and shape our collective memory and future.

Michele Mason is assistant professor of Modern Japanese Literature and Culture at the University of Maryland, College Park. Her research and teaching interests include modern Japanese literature and history, colonial and postcolonial studies, feminist theory, and masculinity studies. She also continues her engaged study of the history of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, nuclear studies, and peace and nuclear abolition movements. Mason co-produced the short documentary film entitled Witness to Hiroshima (2008). Link

Recommended citation: Michele Mason, “Writing Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the 21st Century: A New Generation of Historical Manga,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 47-5-09, November 23, 2009. 世紀において広島・長崎を書くーー新世代の歴史マンガ

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Yuki Tanaka and Matthew Penney for their invaluable comments. To Kōno Fumiyo and Nishioka Yuki I owe a great debt for writing these two important manga and for allowing me to reprint images. The encouragement and suggestions I received from Masayuki Shinohara, Mariana Landa, Angela Yiu, Laura Hein and participants at the Revisiting Postwar Japan Conference (May 2009, Sophia University) are greatly appreciated. As always, a very special thank you to Leslie Winston for her witty and never waning support.

Notes

1 Tessa Morris-Suzkui, The Past Within Us: Media, Memory, History (London: Verso, 2005), 177.

2 The two stories were originally published separately in the youth-oriented weekly serial Weekly Manga Action in 2003 and 2004, and debuted as a single volume in 2004. The response to Kōno’s work has been impressive. A radio drama version was produced in 2006, and both Sasabe Kiyoshi’s live-action film and Kunii Kei’s novel adaptation came out in 2007. The Japan Media Arts Festival awarded Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms the Grand Prize for manga in 2004, and it received the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize Creative Award in 2005. Both the film and actor who played Hirano Minami, Aso Kumiko, garnered critical acclaim and numerous awards. It has been released on DVD and a soundtrack is available. Last Gasp published the comic in English, and it has been translated into Korean, Chinese and French as well. Kōno Fumiyo, Yūnagi no machi sakura no kuni (Tokyo: Futabasha, 2004). Quotes herein are from the English translation by Naoko Amemiya and Andy Nakatani. Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms (San Francisco: Last Gasp, 2006).

3 Nishioka Yuka, Natsu no zanzō (Tokyo: Gaifūsha, 2008). Gaifūsha produces books that address a wide range of political, economic, and social justice issues. All translations of this work are my own.

4 The contested and complicated use of the word hibakusha is rightly receiving more attention recently. In this paper, however, I use the term interchangeably with the English translation “survivor.” For more information on this subject, see Takemine Seiichirō’s “‘Hibakusha’ toiu kotoba ga motsu seigisei” [The Political Aspects of the Word Hibakusha], Ritsumeikan heiwakenkyū, No. 9, (March 2008): 21-30.

5 John Whittier Treat, Writing Ground Zero: Japanese Literature and the Atomic Bomb (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 27.

6 There is plenty of evidence, unfortunately, to confirm this fear in the case of images. Tessa Morris-Suzuki offers one example in The Past Within Us. After Nakazawa Kenji’s Barefoot Gen began serialization in Shōnen Jump in 1972, serious criticism was aimed at his visuals for being too graphic and disturbing. “In response, Nakazawa admits, he was forced to exclude from his testimony some of the darkest images engraved on his memory.” Later he commented, “When I reread my own work, my flesh crawled with loathing. I fell into a state of thinking ‘how could I have done it so badly?’ And this was so painful that I could not bear it. I immediately hid the magazines in which my work was serialized in a drawer. The plot of Gen kept running through my head, but I had spent half a year trying to alter my mood by writing entertainment comics (Nakazawa 1994, 215).” Morris-Suzuki, The Past Within Us, 162-63.

7 Treat, Writing Ground Zero, 26.

8 Ibid., 27.

9 Ibid., 26.

10 Anna Richardson, “The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” eSharp No. 5 (2005): 1-19.

11 Richardson, “The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” 7.

12 I am thinking here of, for example, the 2008 discovery that the best-selling work Misha: A Memoire of the Holocaust Years was completely fictionalized and written by a Belgium woman who was not Jewish, the scandal of Herman Rosenblat’s authorial liberties in Angel at the Fence, and the scholarship over the last decade on fake slavery narratives (written by white abolitionists) and “autobiographies” about if not by people of the first nations (e.g. Asa Carter’s The Education of Little Tree). One excellent example of this scholarship is Laura Browder’s Slippery Characters: Ethnic Impersonators and American Identity (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2000). Richardson’s article treats Binjamin Wilkomirski’s Fragments (1995), which was marketed as a “memoir” and “personal testimony.” A controversy over its categorization erupted when it was revealed that the author, whose real name is Bruno Dösseker, was a non-Jewish Swiss national. It has not been reprinted since 1999.

13 Richardson, “The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” 9.

14 Ibid., 5-6.

15 Ibid., 7.

16 Art Spiegelman, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale II: And Here My Troubles Began (New York: Pantheon Books, 1991), 46.

17 Sara Horowitz, “Auto/Biography and Fiction after Auschwitz: Probing the Boundaries of Second-Generation Aesthetics,” in Breaking Crystal: Writing and Memory after Auschwitz, Ed. Efraim Sicher (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 278.

18 Horowitz, “Auto/Biography and Fiction after Auschwitz: Probing the Boundaries of Second-Generation Aesthetics,” 277.

19 For excellent translations and commentary on the work of the first three writers see Richard H. Minear, Hiroshima: Three Witnesses (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990). John Bestor’s wonderful translation of Ibuse’s Black Rain (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1988) stands the test of time. Another important resource for short stories by both survivors and non-survivors is the anthology edited by Ōe Kenzaburō The Crazy Iris and Other Stories of the Atomic Aftermath (New York: Grove Press, 1994).

20 Stephen C. Feinstein, “Mediums of Memory: Artistic Responses of the Second Generation,” in Breaking Crystal: Writing and Memory after Auschwitz, Ed. Efraim Sicher (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 201.

21 I use the term “manga memoir,” cautiously, realizing the contentious issues surrounding the definition of such a reference. It brings to mind an interview (conducted by Stanley Crouch) on the Charlie Rose Show (July 30, 1996), wherein Art Spiegelman asserts, “I kind of like living in the space between categories” when he explains that he wrote the New York Times to complain that his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, Maus, had been listed as “fiction” on the bestseller list. He adds that he would “have done so no matter which side of the list it had appeared on.” (link)

22 Subsequent anime and live-action film adaptations and the completion of the full English translation attest to Barefoot Gen’s wide reach and long lasting popularity. Yamada Tengo directed three live-action adaptations, which came out between 1976 and 1980. Barefoot Gen (1983) and Barefoot Gen 2 (1987) were both created by Mori Masaki. The English translation of Volume 10 of the manga Barefoot Gen was released November 2009.

23 For more details see the interview of Nakazawa Keiji in Japan Focus. Nakazawa Keiji, “Barefoot Gen/The Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy.” (link)

24 Kōno, Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms, 103.

25 Ibid.,103.

26 Ibid.,104.

27 Ibid.,102.

28 Nishioka, Natsu no zanzō, 133.

29 Ibid., 133.

30 Nishioka writes, “Thinking I would engrave this day on my heart, I gave my protagonist the name ‘Kana’” (133). Michael Rothberg’s excellent new work, entitled Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization, speaks to how collective memory emerges out of a dynamic process that is frequently inspired and shaped by seemingly unrelated events in time and place. One of the most important interventions of this book lies in Rothberg’s notion of “multidirectional memory,” which he characterizes as “subject to ongoing negotiation, cross-referencing, and borrowing; as productive and not privative” (3). Thus, in the same way that the Algerian War constituted a cite of “transfer,” which stimulated articulations of memories of the Holocaust, the production of A Summer’s Afterimage can be attributed in part to Nishioka’s association of the bombing of Qanaa with that of Nagasaki. See Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).

31 Ibid., 137.

32 In 1960, approximately 900 households were located along a strip of land running along the Hon River. In 1968, a development plan was proposed, everyone evicted, and over a span of ten years the land redeveloped. Today, in addition to an apartment complex, there exists a municipal art museum, youth center, swimming pool, and several libraries where the “atomic slum” used to be.

33 For instance, Fujimi Hirano expresses disappointed when her son Asahi, who was in Mito at the time of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, decides to marry a hibakusha. In the contemporary story, Nagio tells the woman he has been dating, Toko, that her parents have instructed him to never see her again because he is a second-generation survivor with a history of health problems.

34 The many writings of Hayashi Kyoko, a survivor of Nagasaki, stand out as particularly important contributions to the genre of Atomic Bomb Literature. Numerous works by Hayashi have been awarded prestigious literary prizes, such as “Procession on a Cloudy Day” (Kumoribi no Kōshin, 1967, trans. Kashiwagi Hirosuke, 1993) and Ritual of Death (Matsuri no ba, 1975, trans. Kyoko Selden, 1984). Readers can also find English translations of her short stories “Empty Can” (Akikan, 1978, trans. Margaret Mitsutani, 1985) and “Masks of Whatchamacallit: A Nagasaki Tale” (Nanjamonoja no men, 1968, trans. Kyoko Selden, 2005). (For the latter work see this link.) Another widely available work in English is Dr. Nagai Takashi’s The Bells of Nagasaki (Nagasaki no kane, 1949, trans. William Johnston, 1984), which can help fill in this overlooked history.

35 This strategy of casting both characters and readers as the audience of oral testimonies recalls Spiegelman’s ever-present tape recorder in Maus.

36 Kōno, Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms, 93-95.

37 See Hayashi Kyōko’s poignant novella “From Trinity to Trinity” (Toriniti kara toriniti e, 2000), which describes her 1999 visit to Los Alamos, New Mexico and, specifically, the Trinity site where the U.S. tested the first atomic bomb. (link)

38 Other historical novels make explicit links between the past and present, especially those that seek to “revise” the historical record in order to place it within the “proper” light of the times. Manga: Hating the Korean Wave and Japanese and the Emperor, although from the opposite ends of the political spectrum, can be considered in this light. Both employ “straw man” devices to present their arguments, building their storylines around contemporary college students discovering the “truth” about the past. In the former, this is facilitated through a debate with Zainichi and Korean exchange students who lose to the “superior” neo-nationalist narrative. In the latter, conservative, authoritarian school officials who attempt to punish a student for not singing the national anthem are shot down and shamed by an older supervisor who uses his personal experience during the war to bolster his authority to speak and teach everyone a lesson. For more on the former work see Rumi Sakamoto and Matthew Allen’s “’Hating “The Korean Wave’” Comic Books: A Sign of New Nationalism in Japan?” (link).

39 Kōno, Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms, 34.

40 Treat, Writing Ground Zero, 55.

41 Ibid., 55.

42 Richardson, “The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation,” 7.

43 Lisa Yoneyama, Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space, and the Dialectics of Memory (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 135-6.

44 Nishioka, Natsu no zanzō, 134.

45 Ibid., 135.

46 These lines come from the poem entitled “One Note for the Creators of Atomic Bombs” whose original first lines read “Creators of atomic bombs! For a short while, lay your hands down and close your eyes!”

47 Kōno, Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms, 33.

48 Jason Thompson, “Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms” in Otaku USA (October 30, 2007).

49 Jason Thompson, Manga: The Complete Guide (New York: Del Rey, 2007), 371.

50 Feinstein, “Mediums of Memory: Artistic Responses of the Second Generation,” 204.

51 Feinstein, “Mediums of Memory: Artistic Responses of the Second Generation,” 202.