Oil and Power: The Rise and Fall of the Japan-Iran Partnership in Azadegan

By Michael Penn

The story of how

The Courtship

On

Iranian Oil Minister Bijan Zanganeh

From

No Japanese foreign minister had visited

Still, tensions remained in the Japan-Iran relationship. Komura reiterated

At any rate, signs of warmth in Japan-Iran relations were apparent throughout the following year. In January 2000, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI, later METI) announced that medium- and long-term trade insurance would be issued to Japanese companies for activities in

In April, after President Khatami’s second great electoral victory, MITI took the initiative to propose a regular dialog with

In the background to MITI’s initiative in proposing regular energy talks with the Iranian government was the loss, in February 2000, of the Japanese-owned Arabian Oil Company’s long-term concession in the Khafji oil field, along the Saudi-Kuwaiti border. That concession had been the jewel in the crown in

In June 2000, Toyo Engineering received a major contract to help build a new petrochemical plant in

This led to the major breakthrough event: the arrival in Tokyo of Iranian President Khatami in October-November 2000. This was the first visit to

Nevertheless, it was still something of a surprise when it was announced that Japanese companies would be given precedence in negotiations for the development of the huge Azadegan oil field. A consortium of Japanese oil companies led by Indonesia Petroleum, Ltd. (the Inpex Corporation) would take the lead in these negotiations.

On the Japanese side, MITI Minister Hiranuma Takeo took the lead in pushing for Japan’s participation in Iranian oil development, in part to compensate for the loss of the Khafji concession, and in part simply to diversify the sources of oil imports from the perspective of energy security. It was thus appropriate that the original agreement between

Newspaper editorials in

In the months following the Khatami visit, the negotiations made good progress. In December, the Japan National Oil Corporation signaled that it too would be willing to participate in the project, and by mid-2001, the Royal Dutch Shell Group entered the discussions to provide technical support. [13]

In July 2001, MITI Minister Hiranuma led an 80-man delegation of business leaders to

However, the issue of the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act (ILSA) remained a stumbling block. Although the moderate President Mohammad Khatami had just been re-elected in another landslide in June 2001, the U.S. Congress remained hostile to the

The First Crisis

The full repercussions of this new political dynamic were not immediately apparent to leaders in

Japanese concerns about U.S. policy toward Iran multiplied when President Bush used his January 2002 State of the Union speech to declare that Iran, together with Iraq and North Korea, were part of an “Axis of Evil” that needed to be confronted by the international community.

At the beginning of May 2002, Foreign Minister Kawaguchi Yoriko was dispatched to

It was clear that the positions of

President Bush’s declaration regarding the “Axis of Evil” and a stream of threats by various American commentators that Iran was second only to Saddam Husain’s Iraq as the country that must be “dealt with,” had thrown the Iranian leadership onto the defensive, and made them even more sensitive to perceived insults from the West and its allies. They were thus not in the mood to be lectured by the Japanese foreign minister about the Israeli-Palestinian issue or about the development of new weapons systems.

For their part,

The Azadegan oil field negotiations proceeded at a much slower pace through the rest of 2002, and the deadline for the completion of the negotiations was quietly extended to the end of June 2003. [24] In early 2003 everyone’s attention was firmly focused on the impending American and coalition invasion of

Nevertheless, with strong political backing from Hiranuma Takeo and what was now called the Ministry for Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI), the Azadegan negotiations quietly moved forward, and as the June 30 deadline approached, all that remained was to sign the agreement.

However, at precisely this point, another issue suddenly appeared that had a negative political impact: the issue of nuclear non-proliferation. On

The Japanese Foreign Ministry quickly released a statement declaring that

But in spite of nuclear concerns, METI officials still intended to sign the Azadegan oil deal as planned on June 30.

The IAEA report had nevertheless given much ammunition to foes of the Japan-Iran oil deal in

Having refrained from signing the Azadegan deal as planned,

Iranian leaders were clearly annoyed by

But

By the beginning of August 2003, Oil Minister Zanganeh was sending positive signals, saying that Japan still had the best chance to win the bidding for the giant oil field, and reminding everyone that, “the oil development project is a symbol of Japan-Iran cooperation, and if there is strong will on both sides, we can conclude an agreement.” [32]

At the end of that month, Iranian Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi arrived in

The Khatami administration was coming under heavy political pressure from many Western countries, as well as from

But in September, Prime Minister Koizumi reshuffled his cabinet, and the METI portfolio was handed to Nakagawa Shoichi, an ideological hawk linked with

Although Nakagawa’s view was completely out of tune with the policy of his predecessor, as well as the bureaucrats under his authority, it was bound to have an effect on the negotiations. The bilateral atmosphere turned chilly once again, and

Near the end of their patience in early December, Iran wrote a letter to Inpex and the other companies involved in the Japanese consortium demanding that they clarify their intentions within one week or be forced to participate in an open, international bidding process for the Azadegan development. Still under pressure from

Bam Earthquake on Dec. 26, 2003.

Then, on December 26, a major earthquake struck Bam in southeastern

The Japanese efforts were genuinely appreciated. This seems to have had the effect of soothing the political tensions that had been developing in the bilateral relationship, and restoring a positive mood.

Meanwhile, the Koizumi administration’s policies toward

In early January 2004, Foreign Minister Kawaguchi made another visit to

All of the main political and economic factors were already on the table: there was the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance to consider; there was also the Japan-Iran “special relationship” which had endured American pressure throughout the Islamic Revolution; there was the loss of Khafji and Japan’s need to better secure its energy sources; there were concerns about Iran’s nuclear development and other weapons programs; there was the “war on terrorism”; there were the limitations of the democratic nature of the Iranian political system; and there was Japan’s growing rivalry with China over oil and gas resources in the Persian Gulf and elsewhere.

The Japanese government is never very forthcoming about explaining the reasons for its actions. Key discussions are usually conducted in-house with only hints leaked to the press. Precisely why did

Raquel Shaoul of

Certainly that played an important role. METI Minister Nakagawa Shoichi had already expressed a very dim view of

On the other hand, the Azadegan negotiations had begun in 2000, and there is little evidence that the

One other possible factor that Shaoul raises, but eventually dismisses, is the “bureaucratic factor.” She describes as “received wisdom” the notion that METI was consistently pushing for the Azadegan deal because of their mandate to ensure

Shaoul is at least partially correct in pointing out these realities, but in the end, the “received wisdom” seems closer to the mark than her revised version. To be sure, neither METI nor the Foreign Ministry is monolithic. Nevertheless, they do have dominant factions and dominant interests which tend to shape their outlooks and even reproduce similar policies for generations. All the evidence seems to suggest that METI (with the exception of Minister Nakagawa) was always highly committed to the project, while the Foreign Ministry was dragged along only reluctantly. It is worth noting that the key senior political allies of the Azadegan development — Hiranuma Takeo, Hashimoto Ryutaro, and, later, Nikai Toshihiro — were all non-ideological Liberal Democratic Party conservatives with strong links to the METI bureaucracy. Nakagawa Shoichi was always a misfit as METI Minister, as most of his base and expertise lay in agricultural policy.

At any rate, the signing of the Azadegan deal in mid-February 2004 was done over the objections of the Bush administration. The reaction in

The signing of the Azadegan agreement came at the same time as

Be that as it may, it was now an indisputable fact that

But beyond the purely financial issues,

A Tale of Three Elections

After the signing of the contract on

Another issue that kept creeping up during the course of the next couple of years was

Broadly speaking, however, the Japan-Iran bilateral relationship and the Azadegan oil development project proceeded reasonably well for the first year and a half after the agreement was signed.

The most crucial factors that would impact the future of the partnership had no direct connection to Azadegan itself: It was a tale of three elections.

The first of these was the

It affected

Indeed, it was those Iranian elections that provided the biggest surprise. The leading presidential candidate was thought to be the “realist” former president, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, or perhaps one of the “reformers”; in fact, the relatively inexperienced and hardline Mayor of Tehran, Mahmud Ahmadinejad, won in a second round landslide. [47]

Iranian President Mahmud Ahmadinejad

The victory of Ahmadinejad heralded a more difficult period for Japan-Iran relations. Although the new Iranian regime still eagerly sought Japanese understanding and friendship, relations between

Finally, in September 2005, a snap election in the lower house was called by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro, and his revamped Liberal Democratic Party scored a landslide victory, crushing the opposition parties.

The significance of this last event was twofold: First, it entrenched an even more conservative regime in

It was the combined impact of these three elections — and particularly the results in

Things Fall Apart

In August 2005,

Still, there remained the issue of

An official at Inpex was quoted as remarking, “If (political backing) for the project ebbs during its first phase,

The comment of the Foreign Ministry official symbolizes the larger fact that the mainstream of the Foreign Ministry was now turning against the Azadegan project. Even at the beginning, officials of this ministry were decidedly unenthusiastic about the partnership with

At any rate, both the Japanese oil companies led by Inpex, as well as METI, were still solidly behind the project, and that did carry some weight. It appears that METI Minister Nikai became the new champion of the energy-security line within the Koizumi Cabinet.

The next blows to the Japan-Iran partnership were once again delivered by President Ahmadinejad.

First, the new president was unable, for several months, to have his appointees to the Iranian Oil Ministry confirmed by parliament. This stalemate dragged on until late in the year.

Second, in a similar vein, the new Iranian president decided to relieve a string of senior Iranian diplomats of their posts in European capitals, thus making it more difficult for

Finally, in a series of speeches in late 2005, President Ahmadinejad adopted a very radical posture, and made outrageous remarks. These included his advocacy of seeing

Through such remarks, the Iranian president effectively positioned himself as a leader of Islamist radicalism, but also alienated moderate and liberal opinion around the globe. In

At about this time,

Mottaki was urbane and pleasant throughout his visit. In interviews with the media he was soft-spoken and reassuring. Nevertheless, on the issues of substance he didn’t give any ground at all. On the other side, Foreign Minister Aso Taro used his meeting with the Iranian delegation to strike a tough pose, making comments such as, “

By mid-March, the first clear indications emerged that

In April, the political climate between

But then

In mid-May — with

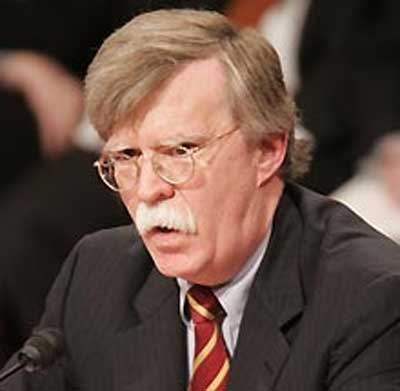

John Bolton, US Ambassador to UN.

John Bolton — the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. — responded the very next day with veiled threats of his own: “

At any rate, in late May, Mehdi Bazargan — an influential Iranian oil official — openly voiced his dissatisfaction with the performance of Inpex in Azadegan. The project was moving forward very slowly, and the Iranians were growing impatient. Officials at the Japanese oil company Inpex blamed these delays on problems in de-mining the area around the oil field, which was necessary to complete first in order to ensure the safety of its workers. Bazargan, however, now asserted that he didn’t “think the main obstacle is mine clearing or de-mining,” but rather Inpex’s hesitation to invest the money that had been agreed due to their concern about the future direction of policy within the Japanese government. In other words, Inpex didn’t want to spend a lot of money if

Throughout the summer, it remained unclear how

Meanwhile, in August, as the fate of the Azadegan project still hung in the balance, Michael J. Green, former member of Bush’s National Security Council and a key “alliance manager,” published an opinion article in the Nihon Keizai Shinbun making an extended case for why

His main argument was clear: “It is contrary to Japanese national interest to take the course of appeasement of

Green then pleaded that “

Green argued that

American arguments like Green’s seemed to have the desired impact in

There was now a definite September 15 deadline for

The Iranians eventually granted an extension of the September 15 deadline to September 30, probably to allow the new administration of Abe Shinzo to make the final decision on this matter.

The new Abe administration quickly backed out of Azadegan. METI Minister Nikai was replaced by Abe loyalist Amari Akira, who showed no interest in championing the project as his predecessor had done. The new line out of Tokyo became that the whole Azadegan project had been a “private business relationship” in which the Japanese government had no direct concern, thus ignoring the fact that the Japanese government itself had launched the first negotiations over Azadegan, and that officials such as Hiranuma Takeo and even Prime Minister Koizumi had previously pointed to the joint development as being “a symbol of Japan-Iran cooperation.” When it was announced that government financing for the project would not be forthcoming, the position of Inpex collapsed, because everyone knew that the Japanese oil company needed loans from public institutions in order to cover the costs of the project.

Accounting for the Collapse

In November 2000, the Japan-Iran partnership had been launched with great hopes and promise for the future. Six years later, the project was dead and the century-long bilateral relationship had sunk into its lowest level. How had this miserable failure come about?

It was understood from the start that

Why did

1) The “unilateral moment” in world affairs that lasted for several years after September 11, and which strongly influenced Japanese perceptions of the global order.

2) The deepening conflict with

3) A generational change within the Japanese leadership, and with it the rise of neo-nationalists whose political priorities differed from those of their immediate forebears.

In the first months after September 11 every major power in the world expressed its sympathy and pledged its cooperation in helping the

Reinforcing this emphasis on the U.S.-Japan Security Alliance was the behavior of the North Korean regime. The nuclear crisis on the

The North Korean factor also played an important role in the political rise of neo-nationalists in

Although it is our contention that the critical factors that led to the dissolution of the Japan-Iran partnership over Azadegan took place in

Every country is wise to diversify its sources of energy, even those rich in oil and gas. If some of

It was nevertheless clear that the

Of course, if

One final aspect of the collapse of the Azadegan deal that should be noted refers back to the “bureaucratic factors” discussed in the context of Raquel Shaoul’s research. As previously noted, the Azadegan project had all along been championed by METI and its allies such as Hiranuma Takeo, Hashimoto Ryutaro, and Nikai Toshihiro; while the mainstream of the Foreign Ministry was reluctant at best.

In the final phase, it appears that METI bureaucrats still supported the deal as necessary for

Above all, with the establishment of the Abe administration, the balance had shifted. Nakagawa Shoichi — who had once declared that, “For us,

Conclusion

The Azadegan story is a dramatic illustration of a political failure.

Ironically, the Japanese withdrawal from Azadegan in October 2006 came at a time when some kind of accommodation between the

This means that previous

Michael Penn teaches at The University of Kitakyushu, and is Executive Director of the Shingetsu Institute for the Study of Japanese-Islamic Relations.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on

Notes

[1] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[2] “Joint Press Statement by the Ministers for Foreign Affairs of Iran and Japan on the occasion of the official visit of Foreign Minister Kamal Kharrazi of the Islamic Republic of Iran to Japan,” December 24, 1998.

[3] Associated Foreign Press,

[4] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[5] “Statement by the Press Secretary / Director-General for Press and Public Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on the Parliamentary Elections in Iran,” February 22, 2000.

[6] For a solid, recent review of the collapse of the Khafji concession, see Ahmed Kandil, “The Political Economy of International Cooperation Between Japan and Saudi Arabia: The Arabian Oil Company as a Case Study,” Annals of the Japan Association for Middle East Studies, No. 22-1, August 2006, pp. 21-61.

[7] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[8] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[9] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[10] Nihon Keizai Shinbun, Evening Edition,

[11]

[12] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[13]

[14] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[15] Kyodo News, “

[16] Comment by the Press Secretary / Director-General for Press and Public Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on the Enactment of the Iran and Libya Sanctions Extension Act of 2001,” August 8, 2001.

[17] Misaki Hisane, “Crucial Days of Negotiations Lie Ahead for ‘Oil Diplomacy’,” Japan Times,

[18] “Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi Sends Letters to the Leaders of

[19] “Dispatch of Prime Minister’s Special Envoy Former Foreign Minister Masahiko Koumura to the

[20] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[21] Misaki Hisane, “No Hurry over

[22] Ibid.

[23] “Visit by Minister for Foreign Affairs Yoriko Kawaguchi to the Islamic

[24] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[25] Statement by the Press Secretary / Director-General for Press and Public Relations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, on the Chairwoman’s Summing-Up Statement of the IAEA Board of Governors Meeting Concerning the Implementation of the NPT Safeguards Agreement in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” June 19, 2003.

[26] Guy Dinmore, “US Presses Japan over Iran Oil Deal,” Financial Times, June 27, 2003; Kanako Takahara, “U.S. Pressure Places Iran-Japan Oil Deal in Doubt,” Japan Times, July 2, 2003; Hooman Peimani, “Americans Stymie Japan-Iran Oil Deal,” Asia Times Online, July 4, 2003.

[27] Hooman Peimani, “Americans Stymie Japan-Iran Oil Deal,”

[28] Kanako Takahara, “

[29] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[30] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[31] “Japan-Iran Disarmament and Non-Proliferation Consultations (Overview),” July 2003.

[32] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[33] “Visit to

[34] Tomoko Otake, “Cabinet Interview: Nakagawa’s Farm Trade Background Brings Mixed Bag to METI Portfolio,” Japan Times,

[35] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[36] Sayuri Daimon, “

[37] Nihon Keizai Shinbun,

[38] Raquel Shaoul, “An Evaluation of Japan’s Current Energy Policy in the Context of the Azadegan Oil Field Agreement Signed in 2004,” Japanese Journal of Political Science, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2005.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Richard Boucher, Spokesman, Daily Press Briefing, State Department,

[41] Richard Hanson, “

[42] Eric Watkins, “Japan Secures Financing to Develop

[43] Kyodo News, “

[44] Eric Watkins, “Japan Secures Financing to Develop

[45] Kyodo News, “

[46] For more on the eventual success of Japanese bids in

[47] For a good analysis of this election, see Shintaro Yoshimura, “Regarding the Ninth Iranian Presidential Elections,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 30,

[48] Mayumi Negishi, “

[49] J. Sean Curtin, “

[50] Quoted in Michael Penn, “The

[51] Ibid.; Mindy L. Kotler, “Unrequited Responsibility:

[52] Michael Penn, “Foreign Minister Mottaki in

[53] Michael Penn, “

[54] Michael Penn, “

[55] See the discussion in Michael Penn, “Will Tehran Call Tokyo’s Bluff?,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 263,

[56] Michael Penn, “The Iranian Ambassador Talks Tough in

[57] Michael Penn, “

[58] Michael Penn, “Inpex in Azadegan: Delay is Not an Option,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 284,

[59] A full English translation of Michael Green’s opinion article is available in “All Shook Up –-

[60] Michael Penn, “The Azadegan Saga –- Daneshyar Talks Trash and Nikai Talks Business,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 380,

[61] Michael Penn, “

[62] For a more extended discussion, see Michael Penn, “Azadegan Autopsy, Part II — The North Korea Factor,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 412,

[63] Michael Penn, “Azadegan Autopsy, Part I: METI versus MOFA,” Shingetsu Newsletter No. 405,