On the Dawn of a New National Ainu Policy: The “‘Ainu’ as a Situation” Today

Mark Winchester

Article Summary

On 6 June 2008, the Ainu were recognized as an indigenous people. A new set of policies was promised for Autumn 2009 in line with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. This article offers a major review of this policy-making process. It contends that because of the nature of the UN Declaration, the structure of contemporary Japanese politics, and the recommendations of concerned bodies of “experts”, the result has merely been an incorporation of the Ainu within the remit of contemporary neoliberal politics. Taking its inspiration from the writings of the 1970s Ainu poet and thinker, Sasaki Masao, it argues that the time has surely come to ask just why Ainu are repeatedly construed as being somehow in need of “protection”, “aid” and “respect.” and whether or not alternative ways of thinking about Ainu history and politics are possible.

“What we are facing now is neither the ‘Ainu’ as a race (jinshu), nor the ‘Ainu’ as a people (minzoku), but simply ‘Ainu’ as a situation (jōkyō) – a situation in which people call us ‘Ainu’ and the meaning of that ‘Ainu’ comes to constrain our lives”1.

These were the words that the Ainu poet and writer, Sasaki Masao2, used to describe the Ainu predicament. They appeared in the editorial of the first edition of a small circulation newspaper, Anutari Ainu – warera ningen (‘We Humans’, or ‘We of Humanity’), in 19733. They also, however, lay at the heart of Sasaki’s own particular philosophy of just what it has meant to be ‘Ainu’ in both modern and contemporary Japan.

For Sasaki, after the incursion that modernity had made on people’s perceptions of the world, the fact of one’s being ‘Ainu’ – or, indeed, as he often put it in the passive voice – of having been compelled to be so (‘Ainu’ toshite aru koto ni shīrareru), was forever to imply a sense of the Ainu as having become little more than a specific kind of ‘situation’, of having become a kind of harsh and irreversible interpellation. For Sasaki, after modernity, there was no going back to any kind of pre-modern, idyllic, or autonomous Ainu culture or existence, even if one wished to4. To do so would be to merely retroactively accept, but crucially refuse to recognize, the fact that the situation of the Ainu had forever been altered and changed.

The front page of Anutari Ainu’s first edition. Sasaki’s editorial introducing his notion of the “‘Ainu’ as a situation” to a wider audience appears at the back. (Photo: author)

As long as people repeated their appeals to an autonomous Ainu existence, the aporia of being “Ainu” in the modern and contemporary world could never be properly understood as an aporia in and of itself. Modernity had cut them off from the culture of the past. All that remained was what Sasaki Masao referred to in the harshest terms as an “empty carcass” (keigai)5. Now, this past could only ever been seen through the lens of the modern and therefore either as something to preserve or leave behind. Now, the only reason why “Ainu” were “Ainu” was due to a contingent interpellation in the present. If any kind of autonomy were to be discovered again for those, including himself, that he saw as irrevocably thrown into this ‘Ainu’ as a situation, it would have to be found elsewhere.

Over the last six years I have been trying to take a fresh look at the modern history, and historiography, of the Ainu with reference to the thought of Sasaki Masao, and to connect alternative ways of thinking about Ainu history and politics to contemporary Japanese societal and policy attitudes towards them. I believe that if we take Sasaki’s thought seriously then the image of the Ainu as a forever repressed minority, repeatedly construed as being somehow in need of the governmental protection, aid and respect of others must immediately be put aside. This article attempts to make an intervention in light of current developments taking place in Ainu policymaking in Japan, particularly that concerning a new report submitted to government by a Council of Experts on the Implementation of Ainu Policy on 29th July this year. For despite the fact that the oft-reformed (but extremely long-lived!) Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act of 1899 was replaced in 1997 by the current Ainu Cultural Promotion Act, and despite present initiatives to create a new Ainu policy after Japan’s recognition on 6th June 2008 of the Ainu as an indigenous people in the context of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the ‘Ainu’ as a situation has not gone away. Indeed, often in some quite surprising ways, the ‘Ainu’ as a situation “in which people call us ‘Ainu’ and the meaning of that ‘Ainu’ comes to constrain our lives” is very much alive and well. So too are the modern aporias which keep it so.

Political Beginning, or Final Transaction?

Watching the recent developments in Ainu policy making over the last year (2008-2009) has, in many ways, felt like contracting a severe case of déjà vu. It is as if the events which led to the establishment of the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act in 1997 have been repeating themselves: a rushed drafting of resolutions in a period of political instability, the creation of ad hoc consultative bodies to decide on the policy content, the lobbying activities of key Hokkaido politicians, and the heavy emphasis being placed upon the importance of culture, language, multicultural coexistence and identity politics are all factors which characterized the earlier process as well as the present6. However, there are a number of significant features that have colored the process this time around which were not present during the late 1990s. Perhaps the most significant of these is the adoption of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the General Assembly at UN headquarters in New York on 13th September 2007.

While not a legally binding instrument under international law, the UN Declaration sets out both the individual and collective rights of indigenous peoples, including rights to culture, language, identity, but also those concerning health, employment and education. It also emphasizes the rights of indigenous peoples to establish their own governing institutions, prohibits discrimination against them and promotes their full participation in matters which concern them. As a declaration it represents an axiomatic set of guidelines to which UN member states are expected to adhere, and over which they may be taken to account7.

However, as many involved in the lengthy drafting process of the Declaration attest, it has always been somewhat of a gamble as to whether it signals the beginning of a new political process of change – one that radically alters modern international legal norms – or marks out a final transaction – the bottom line so to speak – between sovereign states and their indigenous populations8. The long-time activist and advocate of indigenous rights for the Ainu in Japan, Uemura Hideki, rightly points out that the subjects of UN human rights law can be none other than the member states9. Therefore, the aim of the political process which began in the 1980s to internationally legislate the rights of indigenous peoples has always been about forcing these states to reflect and reconsider their past actions towards these peoples10. The question thus stands today as to just how successful these efforts have been?

When it comes to Japan, the answer to this question is ambiguous. Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States all abstained from voting on the Declaration. Yet despite the fact that all of these states have considerable indigenous populations and many of Japan’s policy makers and advisors look to them as countries with a commanding lead in the field of indigenous policy, Japan voted in favor. The main reason for Japan’s acceptance was the final wording of Article 46 in which it states that “nothing in this declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, people, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act contrary to the Charter of the United Nations or construed as authorizing or encouraging any action which would dismember or impair, totally or in part, the territorial integrity or political unity of sovereign and independent States”11.

While it is the cultural reverence offered to the idea of Japan as a “homogeneous state” (tanitsu minzoku kokka) that is most often commented upon in the English language literature, for many years now the only real points of concern and resistance put up by the Japanese government against legislating greater Ainu rights and recognizing them as an indigenous people in the context of the UN Declaration, have been worries over its compatibility with the Constitution, and the ability to ensure the state’s final say on any kind redistribution of resources that might take place as a result. In other words, it is concerns over the status of state sovereignty that are at issue. This is why, for an equal number of years, organizations like the Hokkaido Utari Kyōkai (now renamed the Hokkaido Ainu Kyōkai, or known by its English name, the Ainu Association of Hokkaido) have repeatedly stated that they are not interested in land redistribution, or any kind of state-like independence. As the official channel between the state and Ainu affairs to date, as well as being the largest organization representing Ainu in Hokkaido, the demands of the Kyōkai, originally mapped out in their Draft Law Concerning the Ainu People of 198412, have been consistently tame and concentrated on educational scholarships and employment assistance in an effort to better the living standards of its members13.

The chairman and directors of the Hokkaido Utari Kyōkai present demands to Hokkaido politicians during a demonstration on 22nd May 2008 (Photo: author)

The Japanese government’s position has, until now, been unwavering. Even in the earlier report of policy suggestions made by the Council of Experts on Implementation of Countermeasures for the Ainu People (Utari taisaku no arikata ni kansuru yūshikisha kondankai), submitted in April 1996, and which led to the formation of the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act, it was said to be “impossible to put the right of self-determination which relates to a decision of political status, such as separation/independence from our country, or to the compensation/restoration of resources and land in Hokkaido, into the basis of the implementation of new measures for the Ainu people”14. Ever since the submission of this report, this has remained, and has been quoted, as the government’s official position. Now, however, it would seem that the provisions made in Article 46 of the UN Declaration have inexorably ensured the state’s final decision as to what might constitute a “partial imparity” to its “political unity”. Japan’s state machinery is now able to recognize the Ainu as indigenous on their own terms.

Different Agents, Same Structure

This recognition came sooner than expected. With the 34th G8 summit scheduled to take place on the banks of Lake Tōya in Hokkaido from 7th July 2008, an opportunity presented itself for Japan to show off its credentials as an ecologically sound nation respectful of its indigenous people as a convenient symbol of closeness to nature15. A number of Hokkaido politicians with allegiances across the political sphere (including scandalized leader of the Hokkaido-based New Party Daichi, Suzuki Muneo16, and current Prime Minister and leader of the Japan Democratic Party, Hatoyama Yukio) gathered together in May to form the House Members Group for Considering the Establishment of the Rights of the Ainu People (Ainu minzoku no kenri kakuritsu wo kangaeru giin no kai).

A Diet Resolution Calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an Indigenous People (Ainu minzoku wo senjūminzoku to suru koto wo mitomeru kokkai ketsugi) was drafted, revised, submitted to, and unanimously passed by the Joint Committee of both Diet Houses on 6th June. The resolution declared that the Ainu are “indigenous to Hokkaido and are an Indigenous People with their own unique language, religious beliefs and culture”17. It promised that government would “engage in the establishment of a comprehensive policy [for the Ainu] through listening to the opinions of high-level experts, and enhance all existing Ainu policy”18. This promise too was swiftly met. Under the authority of then Chief Cabinet Secretary, Machimura Nobutaka19, a new impromptu Council of Experts on the Implementation of Ainu Policy (Ainu seisaku no arikata ni kansuru yūshikisha kondankai) was set up and, just as their predecessors in the 1995-6 Council of Experts, they were given a year to produce recommendations for a new Ainu policy to reflect the new circumstances established by the UN Declaration20.

Aside from the responsibility placed upon the government to respond to the UN Declaration and the symbolic value that indigenous recognition may have had for a G8 summit dedicated to environmental issues, a number of commentators pointed to other factors which may have contributed to the swiftness of the process. For instance, LDP and DPJ worries over the vote-pulling power that such a move might become for Suzuki Muneo’s New Party Daichi, particularly in the Hokkaido gubernatorial elections21, or the (still conceivable) use of the Ainu as a bargaining chip in the ongoing Northern Territories dispute with Russia (much like during the lead up to the Treaty of St. Petersburg in 1875 when it was argued that since Ainu were Japanese, then land such as the Kurils where Ainu lived, was therefore naturally Japan)22. Now that the DPJ have won the general election of August 2009, it is quite possible that DPJ leader, Hatoyama Yukio, who represents the 9th district of Hokkaido, will claim the new Ainu policy scheduled for the Autumn as an Obama-esque moment of liberal human rights legislation23. This could indeed provide the new administration with a certain amount of symbolic cultural value in an attempt to popularize and align the identity of the new government with an America to which in other areas, most notably defense, the DPJ are considering a parting of ways.

Suzuki Muneo in Ainu garb and Hatoyama Yukio greeting marchers during the May demonstration, a month prior to indigenous recognition (Photo: author).

In spite of the packaging, at base, however, there has been very little difference between the structure of these recent developments and those which led to the creation of the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act more than ten years ago24. The political meanderings that set the stage for the drafting of that Act took place during the 1990s realignment of Japanese politics, in which the LDP lost power for the first time in the postwar era. It was drafted and legislated during the switch between the Japan Socialist Party-led Murayama Cabinet and the newly revamped LDP government of Hashimoto Ryūtarō. Indeed, it is possible to group the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act together with a number of other flawed initiatives – or political full-stops – that the Murayama government introduced to try and put an end to the so-called “1955-system” of LDP-led politics. These would have to include the Atomic Bomb Survivors Assistance Act of 1994 and the Asian Women’s Fund set up in 1995 for former “Comfort Women” which excluded the possibility of direct state compensation, but were hyped as important moves on issues that had been left dormant by previous consecutive LDP governments25. In actual fact, what these policies finally achieved was to clear the way of both social and postcolonial baggage for what would become the more neoliberal friendly political environment to come.

This process, like the present one, had been left up to concerned regional politicians and provisional advisory bodies, indicating quite clearly that, as long as the state has the final say on matters of land and resources, little else pertaining to the Ainu is of any real state interest. This was reflected once again in the bureaucratic system organized to overlook the promotion of Ainu culture after 1997. The most pressing responsibility of the current Foundation for the Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture (hereafter FRPAC), as an official corporation (zaidan hōjin), is to make full use of its subsidies provided annually by the national coffers and Hokkaido, and to publicize how that money has been put to use26. As long as a certain degree of quality is ensured by the Foundation’s vetting committee of both Ainu and non-Ainu experts and concerned individuals (working in a private capacity), the government has little reason to be concerned either with FRPAC, or the content of what it produces. In many ways, it is a pure system of disinterested governance27.

For Ainu, the system of cultural promotion currently in place has denoted a large shift in their public persona. Dedicated to the promotion of Ainu culture as one of the “diverse cultures of our country”, the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act was founded on the principle of “realizing a society in which the ethnic pride of the Ainu people is respected”. In the 1996 Council of Experts report, the Ainu were construed as the inheritors of an important national cultural asset in the form of Ainu culture, itself eventually narrowly defined as “the Ainu language… music, dance and handicrafts”28. On the other hand, the 1996 report declared that in no way should the “method of expressing Ainu identity be forced” upon individual Ainu. This caveat was included partly through taking into account the reservations that organizations such as the Asahikawa Ainu Kyōgikai, or Asahikawa Ainu Council, who were against the introduction of new legislation specifically targeted at the Ainu as it would go against the ideals of equality expressed in the Constitution29.

What this meant in practical terms was that while any public expression of Ainu identity was to be left up to the initiative of individual Ainu, Ainu culture – as promoted by the policy and interpreted as being “in crisis” for its survival – and, in particular the Ainu language which was deemed to be the “core of their identity as an ethnic group” (minzoku toshite no aidentiti no chūkaku wo nasu)30, was to be actively encouraged with significant amounts of government money. In many ways this amounted to a kind of emotional blackmail. Those already engaged in cultural activities were set to benefit from the policy. However, those who were not, in order to be regarded highly by the nation as a whole – be visible and imbued with a sense of “ethnic pride” – were expected to show the initiative, on their part, to take part and to be publicly recognized. As Ainu historian Richard Siddle noted back in 2002, the “responsibility for enlightening the Wajin [non-Ainu Japanese] population is laid largely on the Ainu themselves”, and the relevance of cultural promotion activities (as defined under the narrow scope of the law) to the vast majority of Ainu not engaged in cultural activities remains highly questionable31. This, most certainly, has become what constitutes the “‘Ainu’ as a situation” today.

It was indeed a strange moment for indigenous policy making where “self-determination” was translated into “self-responsibility”, but this seems to be the course that Ainu policy in Japan is now is firmly set upon, especially after the most recent Council of Experts report. Notwithstanding the fact that Council member and Tokyo University professor of history Yamauchi Masanori recently hailed the report for its inclusion of welfare measures as a factor not covered by its 1996 predecessor32, this most recent report may actually work to both reinforce and enhance the logic of Ainu cultural promotion because the same schism between individual Ainu initiative and imposed cultural identity is maintained. This is particularly so in the report’s introduction of the notion of “Ainu as individuals” (kojin toshite no Ainu). Yamauchi may be right in claiming that Ainu policy is at “the crossroads of history”, but the changes taking place are a long walk away from those that he imagines.

“Ainu as Individuals”

The report of the Council of Experts on the Implementation of Ainu Policy was presented to Chief Cabinet Secretary, Kawamura Takeo, on 29th July 2009. After agreeing to “solemnly reflect on their history of suffering and work towards putting the various articles of the report into action”33, he promised to establish a committee responsible for Ainu policy within the offices of the Cabinet Secretariat which would begin its deliberations in the Autumn, after the Summer election34.

The report itself stands at a far lengthier 42 pages than the 14 pages of the 1996 report. Praised widely in the media for having included economic and welfare issues, it is separated into three major sections: “Historical Trajectory of the Present Situation”, “Present Situation and Developments Concerning the Ainu People”, and “Future Ainu Policy”), themselves each separated into two to five more subsections. All in all, it would seem that a far more thorough and deliberate effort has been made on the part of the Council members than that leading up to the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act. Yet this is hardly surprising. Whereas in 1995 it was argued that such advisory boards were “not a forum for the balancing of interests, so it is customary to exclude the concerned parties”35, this time, after the lobbying of the Hokkaido politicians, a demonstration outside the Diet under the onus of the Kyōkai, and his energetic involvement in all aspects of the process so far, the Council included the President of the Hokkaido Ainu Kyōkai, Katō Tadashi, among its members. Furthermore, the presence of National Institute for Humanities and National Museum of Ethnology professor, Sasaki Toshikazu, and the chair of Hokkaido University’s School of Law and head of its newly established Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, Tsunemoto Teruki – both of whom have been involved with Ainu issues for years36 – ensured that this time the process would be far more exhaustive.

The first meeting of the Council of Experts on 11th August 2008. Ainu Kyōkai Chairman, Katō Tadashi is in the foreground. Across the table is the then Chief Cabinet Secretary, Machimura Nobutaka (Photo: Sankei News)

However, despite the heavy detail in the initial historical section of the report (a whole 17 pages of the total), the central ideas expressed within it consist basically of an amplified and more comprehensive elaboration of its 1996 antecedent. Other than the creation of a national “Ainu People’s Day” (Ainu minzoku no hi), an “Ainu brand” (Ainu burando) for handicrafts, and the call for a new governmental body to “encapsulate the collective will of the Ainu People” (Ainu minzoku no sō-i wo matomeru), all of the other suggestions made in the report are appendages and augmentations of things originally proposed under Ainu cultural promotion.

For instance, the report mirrors that of the 1995-6 Council of Experts in using its exact same words to describe the Ainu language as the “core of Ainu identity as a people” (minzoku toshite no aidentiti no chūkaku wo nasu)37. In a section devoted to policy suggestions concerning the use of land and resources, the report simply calls for a revision and expansion of the current Recreation of Ainu Traditional Lifestyle Spaces, or Ioru [Iwor] saisei jigyō, in which Ainu are allowed to use limited amounts of state-owned land to plant and protect wildlife and flora used in traditional handicrafts, food and construction, should they so wish38. The report also reiterates the original idea behind these “spaces” as symbolic “parks or other such facilities” of “ethnic coexistence” (minzoku kyōsei) in which Ainu history and culture can be displayed, taught and experienced first hand, in which traditional handicrafts can be practiced and passed down, in which memorial services can be carried out for important cultural property (such as remains still held by national universities), and in which Japanese nationals, regardless of ethnicity, can gather and gain a physical experience of Ainu culture through active exchange39. A comparable model might be something like Tjapukai Aboriginal Cultural Park in Cairns, Australia – an exciting and interesting venture in national education, but hardly top of the list when it comes to exercising indigenous rights (or, for that matter, the reality of the Ainu situation in Japan)40.

As to what is new in the report, much of what has been proposed here too would fall within FRPAC’s original remit. The heavy emphasis on history and the teaching of that history throughout the standard compulsory education period in a manner appropriate to each academic level represents only an expansion of FRPAC’s activities beyond its present efforts in distributing materials to elementary school and junior high school children41. The national “Ainu People’s Day” – perhaps mimicking Australia’s National Sorry Day – that has been proposed to be held on 6th June to commemorate national recognition of the Ainu’s indigeneity, is aimed at educating the public at large through events displaying Ainu culture across the country. Once again, however, there is nothing in the report on just who will be responsible for displaying Ainu culture at these events.

Moreover, without reference to the more general history of Japanese colonialism it is unlikely that introductions to Ainu history in relation to the history of Hokkaido, and Ainu culture in the form of language, beliefs, closeness to nature, pre-modern lifestyles, food, clothing and handicrafts (all covered by the FRPAC booklets which the report asks be produced on a much larger scale), will be of much tangible interest to people without previous contact with Ainu. Hardly a substitute for real anti-discriminatory legislature, one might compare the experience of being compelled to learn about Ainu history and culture for the majority of the Japanese population as that of being introduced to a rare new animal or bird.

The much-hyped recommendations for economic and welfare measures contained within the report also continue to fall far short of the kind of provisions for agriculture, fishing, forestry, commercial and manufacturing activities, as well as the self-reliance fund, originally called for by the Hokkaido Ainu Kyōkai’s 1984 draft law42. All that is suggested under the section concerning industrial issues is the establishment of an “Ainu brand” as a way to protect Ainu cultural knowledge and further utilize it for regional, touristic and economic benefit43. As for welfare, the report fails to outline any specific policies other than to state that a nationwide survey is necessary to better gauge Ainu socioeconomic conditions44.

And here the report runs once again into the contradiction that lay at the heart of Ainu cultural promotion: how to legislate for Ainu when not all Ainu are engaged in the kind of cultural activities you are trying to promote, and, may not even choose to publicly declare themselves as Ainu. The latter is generally only ever explained by the continued presence of discrimination, as opposed to personal preference. The answer to the former provided in the report is to see the “Ainu as individuals”. This is initially explained with reference to Article 13 of the Constitution (“All of the people shall be respected as individuals”) and linked to the notion that it is only through the sense that Ainu have of themselves as a people (minzoku), that their individuality can be assured45. It is then suggested that to draft policy with “individuals who have an Ainu identity” (Ainu no aidentiti wo motsu kojin) as its subject will ensure that any new Ainu policy will not be limited to certain regions over others (a demand which has been forcefully argued by Ainu living in the Kantō region who have fallen outside of Ainu policy limited to Hokkaido)46.

The report is careful to relate the fact that not all Ainu should be forced into being the subject of the new policy. This is because “Ainu choose to live in a variety of different ways”47. However, at the same time, the report claims that it is according to the socioeconomic disparities between Ainu and the rest of the population that the choice to have and show pride in one’s identity as Ainu is hampered and thus a complex and difficult situation for the maintenance of Ainu traditions and the promotion of Ainu culture has ensued48. Viewing the “Ainu as individuals” would seem to be an attempt to circumnavigate this fact so that even if some Ainu are to receive economic or welfare benefits, they need not feel obligated to engage in cultural activities. Yet it is those very cultural activities that are being held up as the epitome of Ainu pride and identity!

For many years now those involved in Ainu cultural activities have proclaimed that more and more Ainu would feel free to come forward and participate in public expressions of their “ethnic pride” and “identity” should measures be taken to tackle the negative socioeconomic legacy of the modern treatment of the Ainu on their contemporary lives. However, this view seems fundamentally flawed. After all, why should people be expected to “come out” and express themselves after economic disparities have been alleviated? What benefit is there in a public declaration of the fact that one is Ainu other than to receive the blessings of a newfound non-Ainu Japanese “respect”? As the notion of “Ainu as individuals” already seems set to incontrovertibly alter the state of Ainu political organization49, once again the burden of any new policy’s success is being placed on the self-responsibility and initiative of individual Ainu to take part50. It is a key tenet of a neoliberal form of governance which “figures individuals as rational, calculating creatures whose moral autonomy is measured by their capacity for ‘self-care’ – the ability to provide for their own needs and service their own ambitions”, regardless of the historical and social circumstances that might actually hinder their capacity to do so51.

It would seem to most onlookers almost self-explanatory that proper anti-discrimination legislation would go far further than any specific Ainu policy to deal with discrimination and moreover, would benefit others facing discrimination in Japan. Questions also need to be asked about the necessity of state financial backing to “revive”, pass on and maintain a culture, as well as the unintended consequences that this can cause. Other than this there is little preventing Ainu from living today with a sense of pride in their identity and history. That is, of course, minus discrimination and the presence of the current non-Ainu Japanese and state concupiscence towards showing them “respect”.

The Birth of the “Former ‘Former Native’”

Let us return again to Sasaki Masao. In saying that all that was left of the Ainu in contemporary Japan was this “‘Ainu’ as a situation”, “in which people call us ‘Ainu’ and the meaning of that ‘Ainu’ comes to constrain our lives”, he was calling attention to a curious double-bind in which Ainu were forced to internalize their interpellation at the hands of others. For the Ainu, the promises of Japanese modernity had to be reasoned with from a position deemed to be perpetually neither quite modern, nor free, enough.

One might do well here to remember, for instance, the legal term kyū-dojin, or “former natives”, used to refer to the Ainu throughout much of their modern history52. What does it really mean to be a “former native”? To be, both at one and the same time, “formerly native”?

On the one hand, to be “native” is to be paradoxically, but irreducibly modern. “Natives”, as such, can only ever be identified from the perspective of the modern and, indeed, serve to provide that perspective with its very own living, breathing proof of its legitimacy. How else would the smartly-dressed Meiji businessman be able to demarcate himself as a fully modern individual without the contemporaneous presence of the “peasant”, or the “native”? On the other hand, to be “formerly native” implies that one is somehow beyond the phase of this modern “native”, that one is no longer bound to its presumed pre-modern traits. At the same time though, to be marked out as a “former native” is to be perpetually so. In short, to be a “former native” in modern Japan offered little more than the opportunity to declare one’s sense of modern subjectivity and membership to that nation, only to the extent that one remained in a position that was forever not quite there yet.

Just as elsewhere in Japan’s multiethnic Empire, we can say that the granting of formal nationality by no means ensured any sense of practical national belonging to the national community for Ainu. The problem at the heart of Ainu history and politics is thus not concerned with their incorporation within the borders of the modern Japanese nation-state – as is often claimed – but that, once incorporated, the Ainu were not treated as equal participants in the modern life of that nation53. Ever since the official incorporation of Ezochi (Hokkaido) to the modern Japanese polity, legitimized by the establishment of the Russo-Japanese border by the Treaty of Shimoda in 1855, Ainu have, for one reason or another, been perceived of as not quite there yet, and thus in need of the protection of others – hence their unequal status54.

Although one might be persuaded otherwise due to the replacement of the Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act with the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act in 1997, and the current efforts to create a new Ainu policy in light of the UN Declaration, this situation has not really gone away. While the Ainu are no longer seen to be in need of “protection” as “former natives” somehow naturally hindered along the road to further development and modernization, today, these attitudes have been reconfigured in the notion that Ainu are in dire need of the “understanding” and “respect” of the Japanese public at large – and, worryingly and more controversially speaking, in the sense that they are in need of always-ever-better human rights55. They are still, it would seem, perpetually not quite there yet.

As Sasaki once put it, “‘pride’ is always thought of in relation to something that one may be proud of. If ‘being Ainu’ is in itself something to be ‘proud’ of, then either this means that not being ‘Ainu’ is something to be ashamed of, or ‘being Ainu’ used to be thought of as something to be ashamed of; it is either one or the other”56. However, for Sasaki, being “Ainu”, or being in the ‘Ainu’ as a situation, was “not something one can be proud of, nor something with which to be ashamed”57. Rather, for him the question was why people were urged and compelled into these feelings.

Ainu are now expected to live and express themselves “freely” in a “society in which their ethnic pride is respected”. Respected, of course, by the same state and people who imagine they have the capacity to value what they perceive to be an asset to the nation as a whole, and who had previously tended not to value this supposedly self-explanatory “ethnic pride” at all. In other words, while previous injustice towards the Ainu is gradually being “recognized”, and attempts are being made to assume some kind of responsibility for them, these efforts are still those of repentant non-Ainu Japanese and their take on contemporary Ainu life. In this sense, to be the object of “respect” in Japan today should be a quite frightening reminder to the majority of Ainu that the power to publicly value their existence, or their history and culture, does not lie with them58. They are being forever reminded that today, Ainu are only ever really former “former natives”.

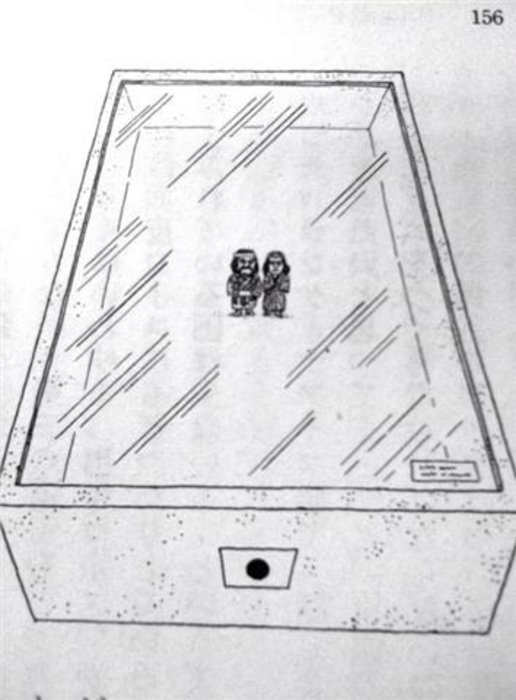

A cartoon which originally appeared in an article in the Asahi Journal by journalist Honda Katsuichi in 1991. Although Sasaki was critical of Honda’s Ainu advocacy in the 1970s, the sentiment behind this particular cartoon could be said to be still relevant today59.

Against this, Sasaki Masao consistently stressed that Ainu today, himself included, must disassociate and de-identify with the notion of being ‘Ainu’ in a difficult act of self-alienation. Indeed, viewing the “‘Ainu’ as a situation” itself is an attempt on his part to do this. Only then would the Ainu cease to be an object, not quite there yet, to be saved by others, and only then would others cease to try and save them. In many ways I see Sasaki’s efforts to “de-identify” (datsu-dōitsuka), or “self-alienate” (tajika suru) himself from being merely “Ainu” and see himself as part of the “‘Ainu’ as a situation” as a similar phenomenon to the notion of the remnant which is being explored in contemporary political philosophy60. Sasaki did not deny his Ainu-ness. He saw himself as irrevocably interpellated into the “Ainu” as a situation. But he saw it as precisely that – a situation, not an identity. In this sense, to have a part of you perpetually defined by others means to be forever missing oneself. It meant an awareness of what Sasaki would call an, “I who should have had to begin as an I without qualification” (keiyōku no nai watashi kara hajimaranebanaranakatta hazu no watashi)61. To be perpetually not there yet also means that there is something else other than just “getting there”. It is a present and immanent experience that is unredeemable, a remnant of the process through which Ainu entered modernity – a present experience not to be solved for a better future, but to be used in the now. In practical matters this kind of self-alienation would certainly necessitate a refusal of current Ainu policy initiatives.

In an age when identity politics is at the heart of contemporary Ainu policy in Japan, I believe that Sasaki’s notion that being in the “‘Ainu’ as a situation”, of never fully coinciding with oneself due to a part of oneself having been irrevocably brought into being by others – a kind of non-identity of sorts – could now be more crucial than ever as the most radical point of entry into modern and contemporary Ainu history and politics.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank ann-elise lewallen for her thorough reading of this paper and suggestions for improvement. All opinions and any errors and misinterpretations are mine alone.

Mark Winchester is a Junior Fellow at the Graduate School of Social Sciences, Hitotsubashi University, Japan. His recent PhD thesis was titled, “A History of Modern and Contemporary Ainu Thought: With a Focus on the Writings of Masao Sasaki” (in Japanese). He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

He can be contacted at: [email protected]

Recommended citation: Mark Winchester, “On the Dawn of a New National Ainu Policy: The ‘“Ainu” as a Situation’ Today,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 41-3-09, October 12, 2009.

See the following articles on related themes:

Chiri Yukie, The Song the Owl God Himself Sang. “Silver Droplets Fall Fall All Around,” an Ainu Tale

Katsuya HIRANO, The Politics of Colonial Translation: On the Narrative of the Ainu as a “Vanishing Ethnicity”

ann-elise lewallen, Indigenous at last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir

Chisato (“Kitty”) O. Dubreuil, The Ainu and Their Culture: A Critical Twenty-First Century Assessment

Notes

1 Sasaki Masao “Henshū Kōki” in Anutari Ainu Kankōkai eds., Anutari Ainu – Warera Ningen, Inaugural Edition, 1st June 1973, p. 8. (Note: all translations from Japanese are my own unless otherwise stated. All Japanese names have been rendered first name-surname for ease of reading).

2 Born in Bibai City, Hokkaido, Sasaki Masao started writing poetry in his twenties, and then went on to study the intellectual history of the Emperor-system of ancient Japan at Tōhoku University in Sendai. His first, and only, poetry collection, which is evocative of Ainu-related themes, ‘Poetic Draft of Eight Verses for a Cursed Soul: One Verse Attached’ (Jukon no tame no happen yori naru shikō tsuki ippen, Shinyasōshosha) was published in 1968. While continuing to write poetry, Sasaki went on to write a number of highly idiosyncratic articles and essays, in a period lasting from 1971 to 1975, using current events involving the Ainu as a way to elaborate on his own personal philosophy and thought about what it means to be ‘Ainu’ in contemporary Japan. He is perhaps best known among people involved in Ainu affairs as the first editor of the Anutari Ainu newspaper during the year 1973-1974. Until recently Sasaki’s output during this period has only been known about by a select few with access to the original publications, however, in 2008, a collection of his articles and poetry was published by Japanese publisher, Sōfūkan (Sasaki Masao, Genshi suru Ainu, Sōfūkan, 2008). While this collection serves as a good introduction to his work it contains a number of typographical errors and omissions, and provides no biographical information about its author. I have written a more detailed account as my PhD thesis which attempts to tease out the implications that Sasaki’s work as a whole might have for Ainu history, politics and thought today.

3 The Anutari Ainu newspaper was printed and distributed on a monthly and bimonthly basis by a close-knit editorial board of young Ainu, predominantly women, and produced out of an apartment building in Sapporo from June 1973 to March 1976. A thousand copies were printed each issue, with around six hundred of these sent to subscribers around the country. Containing a wide variety of poetry and prose, it also dealt with a variety of issues important to Ainu affairs at the time. It folded in 1976 due to lack of funds and the other commitments of the editors.

4 While I do not wish to get into a discussion on the subject of just “what” or “when” constitutes modernity in Japan, suffice it to say that the key element of that modernity involved the organization of human life around an unchanging, static, fixed quantity of time, objectified in the time of the clock, and which is commodified into an abstract exchange value that enables translation and comparison between fundamentally different qualities of the environment and cultural life (See, for example, Karl Marx Grundrisse, Penguin, 1973[1857], pp. 140-143; Walter Benjamin, “Thesis on the Philosophy of History” in Illuminations, translated by Harry Zohn, Fontana/Collins, p.263; E. P. Thompson, “Time, Work-discipline, and Industrial Capitalism”, in Past and Present, No. 38, pp.52-97; David Harvey The Condition of Postmodernity, Blackwell, 1989; and for an overview of Japan: Narita Ryūichi, “Kindai nihon no “toki” ishiki”, in Toki no chihō-shi, Yamakawa Shuppansha, 1999, pp. 352-385). This time of modernity is also, of course, intrinsically linked with the establishment of the structure of global historicist time as the “more developed” shows the “less developed” an image of its own future. As elsewhere, Japanese modernity was legitimized along these historicist grounds. The creation of colonial space in territories such as Hokkaido enabled a “synchronicity of the non-synchronous” as Ainu were perceived to be pre-modern or underdeveloped. Thus modernity’s abstract and empty time provided its own catalyst for application in reality. It is for this reason too that Japanese colonialism should be at the heart of any discussion of modernity in Japan, and indeed East Asia as a whole, and not because of any particular “postcolonial” academic fad or perceived need to supply it with lip-service.

5 Sasaki used the word “carcass” (keigai) to describe Ainu culture in an article which reviewed some of the media reaction to a short documentary film, “An Ainu Wedding” (Ainu no kekkonshiki), by director, Tadayoshi Himeda, made in 1971. In that article, Sasaki laid out his historical understanding of the “dismantling of Ainu communality” in the early modern and modern eras of Japanese history. Most important here, however, is Sasaki’s sense of a decisive historical break that modernity brought to the Ainu. In his words, “exactly where is ‘Ainu culture’ now without its former sense of community, belief and language? All there is now is an empty carcass. To “pass on” something non-existent, even if one wishes to – this is the “Ainu” today” (Sasaki Masao, “Eiga ‘Ainu no kekkonshiki’ ni fureta Asahi Shinbun to Ōta Ryū no bunshō ni tsuite”, in Aen, Aenhenshūshitsu, 1971, pp. 16-30, p. 22). Again, what is crucial to note here is not an argument about whether or not “Ainu culture” exists today as versions of it certainly do. What is vital to grasp in what Sasaki says is the fact that however one may wish to “revive”, “promote”, or “regain” that culture, it will remain exactly that – a revival and nothing more because of the historical break that modernity represents.

6 It is significant to note that those politicians who have been historically most involved in Ainu politics have belonged to the old Tanaka and Takeshita factions of the LDP who came to prominence during the 1993 political crisis and who are now once again in the limelight under the DPJ’s Hatoyama administration.

7 The full text of the Declaration can be found on the UN website. (accessed 13/08/09).

8 See, for instance, Patrick Thornberry Indigenous Peoples and Human Rights, Manchester University Press, 2002, p. 428.

9 Uemura Hideaki, “’Senjūminzoku no kenri ni kansuru kokurensengen’ kakutoku no nagai michinori”, in PRIME, No. 27, pp. 53-68, p. 54; Uemura Hideaki, “Nihon seifu to nihon shakai ga oubeki gimu: Ainu minzoku to senjūminzoku no kenri”, in Impaction, No. 167, Imapact Publishers, 2009, pp. 62-73, p. 62. Uemura has also produced a report on how the Declaration can be applied in the Ainu’s case, Uemura Hideaki, Ainu minzoku no shiten kara mita ‘Senjūminzoku ni kansuru kokusai rengō sengen’ no kaisetsu to riyōhō, Shimin Gaikō Center Booklet No. 3, October 2008.

10 Uemura, ibid.

11 UN Declaration, ibid, Article 46.

12 The drafting of this law marked a shift in the stance of the Kyōkai which had until then held the position that the presence of the Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act on the legislative books would provide more of a point of leverage than nothing at all for a more comprehensive Ainu policy. For an English translation of the law, see Appendix 2 in Richard Siddle, Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan, Routledge, 1996, pp. 196-200.

13 In many ways, the postwar stance of the Kyōkai has reflected the continuation of its status as a semi-governmental organization, originally created as a largely agricultural co-operative movement on 18th July 1930. Having always received an annual subsidy from the Hokkaido government, it has had to depend on the state for its power, and thus also for its membership numbers to which it distributes government policy funds. As such, with a politically conservative base membership engaged predominantly in the agricultural, forestry, fishing and manufacturing sectors, the Kyōkai has always focused on educational and employment issues. It has been difficult to translate these concerns into the language of international indigenous rights. See Siddle, as above, pp. 133-140, 147-153, 180-184, and David Howell, “Making ‘Useful Citizens’ of Ainu Subjects in Early Twentieth Century Japan”, in The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 63 No. 1 (Feb 2004), pp. 5-29.

14 Report of the Council of Experts on Implementation of Countermeasures for the Ainu People, p. 5. Reproduced in, Hokkaido Utari Kyōkai ed., Kokusai kaigi shiryō shū, Shadan Hōjin Hokkaido Utari Kyōkai, 2001, pp. 229-262, p. 243 (hereafter “1996 Report”).

15 Ainu were included in the cultural exchange program organized for the spouses of the G8 leaders in which they were lined up and photographed (on the suggestion of Hokkaido Mayor, Takahashi Harumi) wearing embroidered ruunpe Ainu robes. For the impact of the summit and indigenous peoples events organized to coincide with it, see ann-elise lewallen, “Indigenous at Last! Ainu Grassroots Organizing and the Indigenous Peoples Summit in Ainu Mosir” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 48-06-08, 30th November 2008. (accessed 13/08/09). It was also cited as being potentially significant to have the Ainu recognized as indigenous in a year in which the G8 summit was being held in Hokkaido, the “indigenous land of the Ainu people who make coexistence with nature a fundamental feature” of their lives. See, Diet Resolution Calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an Indigenous People, Resolution No. 1, 169th Diet, (in Japanese). (accessed 13/08/09).

16 Despite his praise of Japan as “one state, one language, one nation” made at a meeting of the Tokyo Foreign Press Club in 2001, and statement to the effect that the Ainu are completely “assimilated”; Suzuki has been heavily involved in Ainu politics throughout his political career. His political influence and the shadow he has cast on Ainu politics are perhaps best illustrated by his role in the appointment of a key supporter of his, Sasamura Jirō, as President of the Utari Kyōkai in the lead up to passing the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act, and also his appointment of Tahara Kaori as a New Party Daichi candidate in the 2005 general election. See, Richard Siddle, “An Epoch-Making Event? The 1997 Ainu Cultural Promotion Act and its Impact”, Japan Forum, Vol. 14 No. 3, 2002, pp. 405-423, pp. 417-418, and the Japan Times article, “Ainu Candidates Political Hopes Hinge on Controversial Figure.” (accessed 13/08/09).

17 Diet Resolution Calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an Indigenous People, ibid.

18 Diet Resolution Calling for the Recognition of the Ainu People as an Indigenous People, ibid.

19 For some it was somewhat ironic that the Chief Cabinet Secretary at this moment was the son of former Hokkaido Mayor, Machimura Kingo, who, in a meeting in 1969 with the then Utari Kyōkai President, Nomura Giichi, had advised against the Ainu being included in the Dōwa Special Measures Law which aimed at raising the living standards and encouraging assimilation among the Burakumin – a nationwide government act. This action, in turn, led to the only regionally based Hokkaido Utari Welfare Measures, under which during a fourteen year period beginning in 1974 over 34 billion yen was funneled into Ainu communities. This was predominantly infrastructure investment and had very little effect on socioeconomic conditions. By the 1990s, rates of interest on loans and low-cost housing which were also covered by the Countermeasures became little different from the commercial sector. See Takeuchi Wataru, Nomura Giichi to Hokkaido Utari Kyōkai, Sōfūkan, 2004, pp. 114-118, and Siddle, Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan, as above, pp. 168-170.

20 The members of the Council were: Hokkaido Ainu Kyōkai President, Katō Tadashi; National Institute for the Humanities and National Museum of Ethnology Professor and historian, Sasaki Toshikazu; Head of Hokkaido University’s School of Law and its Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies, Tsunemoto Teruki; Hokkaido Mayor, Takahashi Harumi; President of the New National Theatre, Tōyama Kazuko; Tokyo University Professor and historian, Masanori Yamauchi (the only member of the Council who was also on the 1995-6 Council); Andō Nisuke, Head of the Kyōto Human Rights Research Institute; and Professor Emeritus of Kyōto University and constitutional law specialist, Satō Kōji – who sat as the Council’s Chair. Whereas this time emphasis was placed on allowing Ainu and Ainu specialists to participate in the process, there was no major symbolic gesture towards placing Ainu policy within the narrative of Japanese national identity as there had been with the nomination of novelist Shiba Ryōtarō to take part last time. However, the result still reflects Shiba’s significant influence on the last panel. See the article, “‘Shiba-shikan’ iro koku hanei” in Hokkaido Shinbun (evening edition), 2 April 1996, p. 10.

21 This point was made by former activist and Ainu historian, Kōno Motomichi, in his article, “Seisō no gu ni sareru senjūminronsō”, Hoppō Jānaru, Vol. 7 No. 1, 2008, pp. 42-43.

22 The author, Russia specialist and former foreign affairs bureaucrat, Satō Masaru, who was arrested alongside Suzuki Muneo on corruption charges in 2002, has consistently made a point of linking Ainu indigenous rights with the Northern Territories issue. See, for instance, Satō Masaru, “Sanshūzenkai icchi de saitaku sareta ‘Ainu senjūminzoku ketsugi’ ga tai-ro ryōdo kōshō no ‘kirifuda’ to naru”, SAPIO, 23/07/08.

23 It is notable that during a meeting with Hatoyama a week before he took office as Prime Minister, Ainu Kyōkai leader Katō Tadashi specifically asked him to mention the Ainu to Obama during their first scheduled meeting. Link (accessed 28/9/09).

24 For a detailed outline and assessment of the impact of that Act, see Siddle “An Epoch Making Event?” ibid.

25 This point is well made by Michiba Chikanobu in his, “‘Sengo’ to ‘senchū’ no aida: jikoshiteki 90-nendai-ron”, Gendai Shisō, Vol. 33 No. 13, 2005, pp. 134-152, p. 143.

26 To this extent FRPAC publishes an annual run down of its finances and how they have been put to use, both online and in print form. This could be argued to have had a detrimental effect and created a source of infighting, even among Ainu engaged in cultural activities, as one can read clearly who is getting what money and what they have done with it each year. There have also been a number of reports concerning the financial embezzlement of FRPAC funds. For FRPAC’s financial reports see their website (in Japanese) here. For reports on the supposed embezzlement of FRPAC funds, albeit fairly hyped, see the January special edition of Hoppō Jānaru, 2004.

27 It is disinterested, of course, from the point of view of the national government. As to FRPAC’s committees, they tend to be made up of Ainu Kyōkai directors, former Council of Expert members, and other interested parties. In this sense, a good deal of nepotism has arisen in deciding who gets what funding for which projects.

28 Act for the Promotion of Ainu Culture, the Dissemination of Knowledge of Ainu Traditions, and an Educational Campaign (Ainu Cultural Promotion Act), Law No. 52, 1997, Article 2.

29 Concern over the opinions of the Asahikawa Ainu Council in making this decision are cited in then Chief Cabinet Secretary, Igarashi Kōzō’s memoir, Kantei no rasen kaidan: shimin-ha kanbōchōkan funtōki, Kyōsei, 1998, p. 187, and Council of Experts member, Masanori Yamauchi’s Sekai article written soon after the presentation of the 1996 report, “Ainu shinpō wo dō kangaeru ka? Minzoku to bunka to kyōzoku ishiki”, Sekai, June 1996, pp. 153-168.

30 1996 report, ibid, p. 8.

31 Siddle, “An Epoch-Making Event?”, ibid, p. 415.

32 Yamauchi Masanori, “Ainu minzoku no songen no tame ni”, Sankei News, 10/08/09. (accessed 13/08/09).

33 “Ainu minzoku no kakusa kaishō… Seifu, gutaiteki kentō he”, Yomiuri Online, 29/07/09. (accessed 13/08/09).

34 This promise was also swiftly met as a ‘Comprehensive Ainu Policy Office’ was set up within the Cabinet Secretariat on 12th August 2009 headed by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism’s Hokkaido Office Councilor, Akiyama Kazumi. Link (accessed 17/08/09). A number of developments have also begun concerning the financing of any new policies. For example, on 28th August 2009, the Ministry of Justice announced its budget for 2010 which included ten million yen for “Human Rights educational activities concerning the Ainu problem”, to be spent on printed and internet promotional materials (Hokkaido Shinbun, 29th August 2009). The Hokkaido branch of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism also announced 21 million yen for surveying the promotion and dissemination of the “traditional culture of the Ainu people” in its 2010 budget on 31st August (Mainichi Shinbun, 1st September 2009). The Hokkaido government has also decided to allocate 200 million yen to its Ioru Saisei programs being carried out in Shiraoi and Biratori (Hokkaido Shinbun, 9th September 2009) (See note 38).

35 This was the explanation given by Cabinet Deputy Vice-Minister, Watanabe Yoshiki, when asked about Ainu inclusion in 1996. See Hokkaido Shinbun 2 April 1996.

36 Both born in Hokkaido, Sasaki is a historian of early-modern Ainu material culture and Tsunemoto is a constitutional law specialist whose involvement in Ainu affairs includes the Nibutani Dam Case of the 1990s.

37 The full text of the report (in Japanese) can be downloaded online from the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s website. (accessed 13/08/09). The reference to the Ainu language as the “core” of their identity appears on p. 35. It is also labeled as the genten, or “source” of their identity on the previous page.

38 For a simple explanation of the Ioru saisei jigyō, including PDF diagrams of how Hokkaido conceives the finished project (in Japanese), see the Hokkaido government website here (accessed 13/08/09).

39 Report of the Council of Experts on the Implementation of Ainu Policy (hereafter “2009 report”), pp. 33-34.

40 The question of comparison, particularly in indigenous studies, remains a complicated one. In many ways the category of the “indigenous” has enabled an easy universalism through which comparative studies on indigenous peoples can be carried out around the world and compared in a similar manner to what Naoki Sakai has called the logic of “co-figuration”. Under the logic of “co-figuration” the “Ainu” are construed simply as a particular Japanese example of the “indigenous” whole. In other words, “co-figuration” is a process through which the often incommensurable is rendered as fixed and unchanging difference according to an overarching logic of symmetry and temporal equivalence (See Naoki Sakai Translation and Subjectivity: On “Japan” and Cultural Nationalism, Minnesota University Press, 1997, p. 52). It is quite clear that the category of the “indigenous” has enabled what are ultimately colonial strategies of comparison and much of the discussion in groups like the UN Working Group on Indigenous Peoples has revolved around how to deal with these issues. A more thoughtful line of comparison might consider something like Sasaki Masao’s logic of the “situation” as laid out here. After all, what might it mean to consider the “American Indian as a situation”, or the “Aborigine as a situation” – i.e. as remnants of the aporia that created the modern world?

41 2009 report, pp. 31-32.

42 See Siddle, Appendix 2, pp. 198-199.

43 2009 report, ibid, pp. 37-38.

44 2009 report, pp. 38-39.

45 2009 report, pp. 27-28. The argument here in the report is derivative of that put forward by liberal political theorists such as Will Kymlicka. Council member Tsunemoto has often quoted Kymlicka in order to highlight the potential compatibility between indigenous rights and the Japanese constitution (See, for instance, his “Constitutional Protection of Indigenous Minorities”, in Hōdai hōgaku ronshū, Vol 51 No 3, 2000. (accessed 28/9/09)). Kymlicka’s argument is that indigenous people are owed self-government because without such rights they are in danger of losing access to a secure societal culture which provides the context in which their rights as individuals are rendered meaningful. It need not be repeated that Kymlicka is predominantly interested in finding a consensus between indigenous rights and the liberal legal frameworks of modern nation states This would be opposed those who highlight the potential of indigenous rights to fundamentally alter such frameworks (For instance, Paul Patton, “Nomads, Capture and Colonization” in Deleuze and the Political, Routledge, 2000, p. 129).

46 2009 report, ibid, pp. 30.

47 2009 report, pp. 39.

48 2009 report, pp. 38-39.

49 Having enjoyed a peak after the introduction of the Utari Welfare Countermeasures in 1974, the membership of the Hokkaido Ainu Kyokai has been undergoing a steady decline. This is due, in some part, to disillusion with its organizational structure, but also because of the more general economic prosperity achieved during the following decades. With a current membership of less than 4000 – representing less than 15% of the official Ainu population of 23,767 in 1999 – the ability of the Kyōkai to remain a representative body for the “Ainu People” is now under question (for Kyōkai membership numbers see this link). As Kyōkai Vice-President, Akibe Tokuhei put it in a recent article, perhaps the most serious implication of the new report for the Kyōkai now is “in what ways we can organize, or, for instance, in what ways can we link an understanding of Ainu as individuals with the perspective of being a Hokkaido Utari [sic] Kyōkai member?” Akibe Tokuhei, “Ima Ainu minzoku wa nani wo subeki ka: jiko ninshiki to kōdō”, Impaction, No. 167, 2009, pp. 12-16, p. 14. There is also talk within the Kyōkai of using the separate population registers, or ninbetsuchō, that were taken when Ainu were entered into the Japanese family register system from 1875-1876, as a method for identifying Ainu today, as well as whether they are qualified to be the beneficiaries of any new policy. This would potentially contradict the Council of Experts report which sees Ainu “identity” as fundamentally self-determined. See Abe Yupo, “Ima sugu ni demo dekiru koto wa aru: Ainu minzoku no yōkyū to senjūken”, Impaction, No. 167, 2009, pp. 17-21.

50 This is particularly noticeable in the opinions expressed by legal specialists and non-Ainu Japanese advocates of indigenous rights when they offer to support Ainu political efforts, but then expect Ainu to get their house in order and come up with a collective set of demands as their part of the bargain. No matter how this is explained away as their not wanting to infringe on the Ainu’s right to self-determination, to ignore a situation in which there is no real consensus – partly due to the legacy of colonialism (from which urban, working class Ainu of mixed-decent are probably now the most deeply affected) – and partly to regional factors such as the fact that various Ainu groups lived spread out across the vast region of Hokkaido, Sakhalin and the Kurils in the first place – resulting in still noticeable regional differences today. Why should it be up to Ainu to deal with this when it is these advocates that want to support them? There are of course grassroots forums with agendas quite different from that of the Ainu Kyōkai, however, this tension between autonomy and the seeking of state and societal resources to underline it still defines the parameters of their actions. As long as being “Ainu” is an interpellation, a “situation” in Masao Sasaki’s sense, then there can be no real autonomy as “Ainu”. That sense of autonomy must be found elsewhere.

51 Wendy Brown, “Neoliberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy”, in Edgework, Princeton University Press, 2005, pp. 37-59, p. 42.

52 The initial re-categorization of the Ainu as “former natives” happened in the last decade of the 19th century as Hokkaido’s immigrant population was growing almost annually by the hundred-thousands. See chapter 2 of Siddle Race, Resistance and the Ainu of Japan, ibid.

53 In this sense, and this sense only, the otherwise self-serving and contradictory claims currently being made against Ainu indigeneity by the political manga artist Kobayashi Yoshinori under the heading “the Ainu as Japanese nationals” (Nihon kokumin toshite no Ainu) are in fact correct. However, Kobayashi has not noticed the aporia through which, after modernity, in order to create a sense of practical national belonging, “the Ainu” had to be construed as forever not quite there yet by their very nature. Instead, he hopes to finally accept the Ainu into the bosom of the national community as equal Japanese nationals free of discrimination and with no need for separate and special indigenous rights. In doing so, however, he manages to illustrate perfectly the fact that it is he who is in possession of a sense of practical national belonging enabling him to accept the Ainu into his community. Despite his reputation as a right-winger, in many ways, Kobayashi is little more than a modern liberal democrat. See, Kobayashi Yoshinori ed., Washizumu: tokushū nihon kokumin toshite no Ainu, Vol. 28, Shōgakkan, 2008.

54 This is also why, for instance, Katsuya Hirano’s notion of “colonial translation”, or the consistent movement of deterritorialisation and reterritorialization, is so important for modern Ainu history. In many ways, Ainu history has been a repetition of these twin movements, from the initial incorporation of Ezochi and the dismantling of the basho tributary fishery system leading Ainu to be thrown into the developing colonial Hokkaido economy (deterritorialization), to state attempts to re-connect and subordinate them to the land in the form of the Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act (reterritorialization), to that act’s failings forcing Ainu to once again flow into the developing economy as seasonal migrant workers, or dekasegi (deterritorialization), to all attempts since to deal with their perceived, and thus materialized lack of development since. See Katsuya Hirano, “The Politics of Colonial Translation: On the Narrative of the Ainu as a ‘Vanishing Ethnicity’”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 4-3-09, January 2009. (accessed 5/10/09).

55 As long as human rights are understood as in the pseudo-Kymlickian sense outlined in the Council of Experts report, and indeed to some extent in the UN Declaration itself, they cannot but remain individualistic and property based; they remain more about reparations and ownership – especially with regards to intellectual property rights – than about establishing a sense of the “commons” to which it could be said that much indigenous thought might actually belong.

56 Sasaki Masao, “Eiga ‘Ainu no kekkonshiki’ ni fureta Asahi Shinbun to Ōta Ryū no bunshō ni tsuite”, ibid, pp. 24-25.

57 Sasaki Masao, “Eiga ‘Ainu no kekkonshiki’ ni fureta Asahi Shinbun to Ōta Ryū no bunshō ni tsuite”, ibid.

58 In this respect, we can say that contemporary Ainu policy has worked to sustain something similar in Japan to what Ghassan Hage has called the fantasy of white supremacy imbued in some forms of Australian multiculturalism. Hage identifies a situation in which White multiculturalists share a sense of practical national belonging with “racists” in that they see their nation as a narrative constructed around a national culture which they have the right to control. Within this kind of situation, any act of acceptance or “respect” can work as an exclusionary force on the accepted. See Ghassan Hage White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society, Routledge, 2000.

59 Sasaki was particularly critical of Honda’s claims at the time that only a socialist society would bring Ainu happiness. See Sasaki Masao, “Honda Katsuichi no sekkyō ni tsuite”, in Anutari Ainu Kankōkai eds., Anutari Ainu – Warera Ningen, Inaugural Edition, 1st June 1973, p. 4. The cartoon is taken from Honda Katsuichi, Senjūminzoku Ainu no Genzai, Asahi Bunko, 1993, p. 156.

60 My thinking on this point is guided by Giorgio Agamben’s The Time that Remains, Stanford University Press, 2005, pp. 44-58.

61 Sasaki Masao, “Kono “nihon” ni “izoku” toshite”, in Hoppō Bungei, Vol 5 No 2, 1972, pp. 60-69.