Japanese and American War Atrocities, Historical Memory and Reconciliation: World War II to Today

Mark Selden

War Crimes, Atrocities and State Terrorism

The controversies that continue to swirl around the Nanjing Massacre, the military comfort women, Unit 731 and other Japanese military atrocities rooted in colonialism and the Asia Pacific War are critical not only to understanding the dynamics of war, peace, and terror in the long twentieth century. They are also vital for understanding war memory and denial, with implications for peace and regional accommodation in the Asia Pacific region and the US-Japan relationship. [1]

This article offers a comparative framework for understanding war atrocities and the ways in which they are remembered, forgotten and memorialized. It examines a number of high profile atrocities in an effort to understand their character and the reasons why recognizing and accepting responsibility for their actions have been so difficult. Neither committing atrocities nor suppressing their memories is the exclusive property of a single nation. The issues examined here begin with atrocities committed during the Asia Pacific War and continue to the present.

What explains the fact that Japanese denial and refusal to provide compensation to victims has long been the subject of sharp domestic and international contention, while there has been relatively little analysis of United States atrocities, less criticism or recrimination for that nation’s commission and denial of atrocities, and still less demand for reparations? What are the consequences of this difference for the two nations and the contemporary international relations of the Asia Pacific?

Among the war crimes and atrocities committed in World War II, the Nanjing Massacre . . . or Rape of Nanjing, or Nankin Daigyakusatsu, or Nankin Jiken (Japanese) or Nanjing Datusha (Chinese) . . . remains the most controversial. These different names signal alternative Japanese, Chinese and international perceptions of the event: as “incident”, as “massacre”, as “rape”, as “massive butchery”.

The Nanjing Massacre is controversial not because the most basic facts are in doubt, although historians continue to contest the number of deaths and the interpretation of certain events. Rather it is controversial because of the shocking scale of the killing of Chinese civilians and prisoners of war in a single locale, because of the politics of denial, and because the relationship between the massacre and the character of the wider war remains little understood despite the outstanding research of Japanese and other scholars and journalists. [2]

Japanese neonationalists deny the very existence of a massacre and successive postwar Japanese governments have refused to accept responsibility for either the massacre or the wider war of aggression in which ten to thirty million Chinese died, explaining why these issues remain controversial. To understand why the Japanese government continues to fight this and other war memory battles in ways that poison its relations not only with its Asian neighbors but also with the United States and European nations requires reconsideration not only of contemporary Japanese nationalism, but also of the Cold War power structure that the US set in place during the occupation.

The US insulated Japan from war responsibility, first by maintaining Hirohito on the throne and shielding him from war crimes charges, second by protecting the Japanese state from war reparations claims from victims of colonialism, invasion, and atrocities, and finally by using its troops and bases both to guarantee Japan’s defense and to isolate it from China, the Soviet Union, and other US rivals.

Before turning to this issue, one other question should be posed: more than six decades since Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War, by what right does an American critically address issues of the Nanjing Massacre and Japan’s wartime atrocities? Stated differently, in the course of those six decades US military forces have repeatedly violated international law and humanitarian ethics, notably in Korea, Indochina, Iraq and Afghanistan. In the course of those decades, Japan has never fought a war, although it has steadfastly backed the US in each of its wars. Yet Asian and global attention continues to focus on Japanese war atrocities and their denial, while paying little attention to those committed and denied by the United States.

Attempts to gauge war atrocities and to understand the ways in which they are remembered and suppressed, require the application of universal standards as articulated in the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials. In an age of nationalism, it is particularly important to apply such standards to the conduct of one’s own nation. The German case, to which I return below, is particularly instructive. Germany, like Japan, was defeated by a US-led coalition, and the US played a key role in shaping institutions, war memories, and responses to war atrocities in both Germany and Japan. [3] Nevertheless, the outcomes in the two nations in the form of historical memory and reconciliation in the wake of war atrocities have differed sharply.

To unravel the most contentious memory wars in the Asia Pacific, I begin by offering a comparative framework for assessing Japanese and American war atrocities. I examine Japan’s Nanjing Massacre and the American firebombing and atomic bombing of Japanese cities during World War II as each nation’s signature atrocities. In each instance, I cast the issues in relation to the wider conduct of the war, and in the American case consider the legacy of the bombing for subsequent wars down to the present. At the center of the analysis is the assessment of these examples in light of principles of international law developed over many decades from the late nineteenth century, notably those enshrined in the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials, and the Geneva Convention of 1949, that identify as acts of terrorism and crimes against humanity the slaughter of civilians and noncombatants by states and their militaries. [4] It is only by considering crimes by the victors as well as the vanquished in the Asia Pacific War and other wars that it is possible to lay to rest the ghosts of suppressed memories in order to build foundations for a peaceful cooperative order in the Asia Pacific.

But first, Nanjing.

The Nanjing Massacre and Structures of Violence in the Sino-Japanese War

Substantial portions of the Nanjing Massacre literature in English and Chinese—both the scholarship and the public debate—treat the event as emblematic of the wartime conduct of the Japanese, thereby essentializing the massacre as the embodiment of the Japanese character. In the discussion that follows, I seek to locate the unique and conjunctural features of the massacre in order to understand its relationship to the character of Japan’s protracted China war and the wider Asia Pacific War.

Just as a small staged event by Japanese officers in 1931 provided the pretext for Japan’s seizure of China’s Northeast and creation of the dependent state of Manchukuo, the minor clash between Japanese and Chinese troops at the Marco Polo Bridge on July 7, 1937 paved the way for full-scale invasion of China south of the Great Wall. By July 27, Japanese reinforcements from Korea and Manchuria as well as Naval Air Force units had joined the fight. The Army High Command dispatched three divisions from Japan and called up 209,000 men. With Japan’s seizure of Beiping and Tianjin the next day, and an attack on Shanghai in August, the (undeclared) war began in earnest. In October, a Shanghai Expeditionary Army (SEA) under Gen. Matsui Iwane with six divisions was ordered to destroy enemy forces in and around Shanghai. The Tenth Army commanded by Gen. Yanagawa Heisuke with four divisions soon joined in. Anticipating rapid surrender by Chiang Kai-shek’s National Government, the Japanese military encountered stiff resistance: 9,185 Japanese were killed and 31,125 wounded at Shanghai. But after landing at Hangzhou Bay, Japanese forces quickly gained control of Shanghai. By November 7, the two Japanese armies combined to form a Central China Area Army (CCAA) with an estimated 160,000-200,000 men. [5]

With Chinese forces in flight, Matsui’s CCAA, with no orders from Tokyo, set out to capture the Chinese capital, Nanjing. Each unit competed for the honor of being the first to enter the capital. Historians such as Fujiwara Akira and Yoshida Yutaka sensibly date the start of the Nanjing Massacre to the atrocities committed against civilians en route to Nanjing. “Thus began,” Fujiwara wrote, “the most enormous, expensive, and deadly war in modern Japanese history—one waged without just cause or cogent reason.” And one that paved the way toward the Asia Pacific War that followed.

Japan’s behavior at Nanjing departed dramatically from that in the capture of cities in earlier Japanese military engagements from the Russo-Japanese War of 1905 forward. One reason for the barbarity of Japanese troops at Nanjing and subsequently was that, counting on the “shock and awe” of the November attack on Shanghai to produce surrender, they were unprepared for the fierce resistance and heavy casualties that they encountered, prompting a desire for revenge. Indeed, throughout the war, like the Americans in Vietnam decades later, the Japanese displayed a profound inability to grasp the roots and strength of the nationalist resistance in the face of invading forces who enjoyed overwhelming weapons and logistical superiority. A second reason for the atrocities was that, as the two armies raced to capture Nanjing, the high command lost control, resulting in a volatile and violent situation.

The contempt felt by the Japanese military for Chinese military forces and the Chinese people set in motion a dynamic that led to the massacre. In the absence of a declaration of war, as Utsumi Aiko notes, the Japanese high command held that it was under no obligation to treat captured Chinese soldiers as POWs or observe other international principles of warfare that Japan had scrupulously adhered to in the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, such as the protection of the rights of civilians. Later, Japan would recognize captured US and Allied forces as POWs, although they too were treated badly. [6]

As Yoshida Yutaka notes, Japanese forces were subjected to extreme physical and mental abuse. Regularly sent on forced marches carrying 30-60 kilograms of equipment, they also faced ruthless military discipline. Perhaps most important for understanding the pattern of atrocities that emerged in 1937, in the absence of food provisions, as the troops raced toward Nanjing, they plundered villages and slaughtered their inhabitants in order to provision themselves. [7]

Chinese forces were belatedly ordered to retreat from Nanjing on the evening of December 12, but Japanese troops had already surrounded the city and many were captured. Other Chinese troops discarded weapons and uniforms and sought to blend in with the civilian population or surrender. Using diaries, battle reports, press accounts and interviews, Fujiwara Akira documents the slaughter of tens of thousands of POWs, including 14,777 by the Yamada Detachment of the 13th Division. Yang Daqing points out that Gen. Yamada had his troops execute the prisoners after twice being told by Shanghai Expeditionary Army headquarters to “kill them all”. [8]

Major Gen. Sasaki Toichi confided to his diary on December 13:

. . . our detachment alone must have taken care of over 20,000. Later, the enemy surrendered in the thousands. Frenzied troops–rebuffing efforts by superiors to restrain them–finished off these POWs one after another. . . . men would yell, ‘Kill the whole damn lot!” after recalling the past ten days of bloody fighting in which so many buddies had shed so much blood.’”

The killing at Nanjing was not limited to captured Chinese soldiers. Large numbers of civilians were raped and/or killed. Lt. Gen. Okamura Yasuji, who in 1938 became commander of the 10th Army, recalled “that tens of thousands of acts of violence, such as looting and rape, took place against civilians during the assault on Nanjing. Second, front-line troops indulged in the evil practice of executing POWs on the pretext of [lacking] rations.”

Chinese and foreigners in Nanjing comprehensively documented the crimes committed in the immediate aftermath of Japanese capture of the city. Nevertheless, as the above evidence indicates, the most important and telling evidence of the massacre is that provided by Japanese troops who participated in the capture of the city. What should have been a fatal blow to “Nanjing denial” occurred when the Kaikosha, a fraternal order of former military officers and neonationalist revisionists, issued a call to soldiers who had fought in Nanjing to describe their experience. Publishing the responses in a March 1985 “Summing Up”, editor Katogawa Kotaro cited reports by Unemoto Masami that he saw 3-6,000 victims, and by Itakura Masaaki of 13,000 deaths. Katogawa concluded: “No matter what the conditions of battle were, and no matter how that affected the hearts of men, such large-scale illegal killings cannot be justified. As someone affiliated with the former Japanese army, I can only apologize deeply to the Chinese people.”

A fatal blow . . . except that incontrovertible evidence provided by unimpeachable sources has never stayed the hands of incorrigible deniers. I have highlighted the direct testimony of Japanese generals and enlisted men who documented the range and scale of atrocities committed during the Nanjing Massacre in order to show how difficult it is, even under such circumstances, to overcome denial.

Two other points emerge clearly from this discussion. The first is that the atrocities at Nanjing—just as with the comfort women— have been the subject of fierce public controversy. This controversy has erupted again and again over the textbook content and the statements of leaders ever since Japan’s surrender, and particularly since the 1990s. The second is that, unlike their leaders, many Japanese citizens have consistently recognized and deeply regretted Japanese atrocities. Many have also supported reparations for victims.

Nanjing Memorial Museum with figure of 300,000 deaths

The massacre had consequences far beyond Nanjing. The Japanese high command, up to Emperor Hirohito, the commander-in-chief, while closely monitoring events at Nanjing, issued no reprimand and meted out no punishment to the officers and men who perpetrated these crimes. Instead, the leadership and the press celebrated the victory at the Chinese capital in ways that invite comparison with the elation of an American president as US forces seized Baghdad within weeks of the 2003 invasion. [9] In both cases, the ‘victory’ initiated what proved to be the beginning not the end of a war that could neither be won nor terminated for years to come. In both instances, it was followed by atrocities that intensified and were extended from the capital to the entire country.

Following the Nanjing Massacre, the Japanese high command did move determinedly to rein in troops to prevent further anarchic violence, particularly violence played out in front of the Chinese and international press. Leaders feared that such wanton acts could undermine efforts to win over, or at least neutralize, the Chinese population and lead to Japan’s international isolation.

A measure of the success of the leadership’s response to the Nanjing Massacre is that no incident of comparable proportions occurred during the capture of a major Chinese city over the next eight years of war. Japan succeeded in capturing and pacifying major Chinese cities, not least by winning the accommodation of significant elites in Manchukuo and in the Nanjing government of Wang Jingwei, as well as in cities directly ruled by Japanese forces and administrators. [10]

This was not, however, the end of the slaughter of Chinese civilians and captives. Far from it. Throughout the war, Japan continued to rain destruction from the air on Chongqing, Chiang Kai-shek’s wartime capital, and in the final years of the war it deployed chemical and biological bombs against Ningbo and throughout Zhejiang and Hunan provinces. [11]

Above all, the slaughter of civilians that characterized the Nanjing Massacre was subsequently enacted throughout the rural areas where resistance stalemated Japanese forces in the course of eight years of war. This is illustrated by the sanko sakusen or Three-All Policies implemented throughout rural North China by Japanese forces seeking to crush both the Communist-led resistance in guerrilla base areas behind Japanese lines and in areas dominated by Guomindang and warlord troops. [12] Other measures implemented at Nanjing would exact a heavy toll on the countryside: military units regularly relied on plunder to secure provisions, conducted systematic slaughter of villagers in contested areas, and denied POW status to Chinese captives, often killing all prisoners. Above all, where Japanese forces encountered resistance, they adopted scorched earth policies depriving villagers of subsistence.

One leadership response to the adverse effects of the massacre is the establishment of the comfort woman system immediately after the capture of Nanjing, in an effort to control and channel the sexual energies of Japanese soldiers. [13] The comfort woman system offers a compelling example of the structural character of atrocities associated with Japan’s China invasion and subsequently with the Asia Pacific War.

In short, the anarchy first seen at Nanjing paved the way for more systematic policies of slaughter carried out by the Japanese military throughout the countryside. The comfort woman system and the three-all policies reveal important ways in which systematic oppression occurred in every theater of war and was orchestrated by the military high command in Tokyo.

Nanjing then is less a typical atrocity than a key event that shaped the everyday structure of Japanese atrocities over eight years of war. While postwar Japanese and American leaders have chosen primarily to “remember” Japan’s defeat at the hands of the Americans, the China war took a heavy toll on both Japanese forces and Chinese lives. In the end, Japan faced a stalemated war in China, but one that paved the way for the Pacific War, in which Japan confronted the US and its allies.

The Nanjing Massacre was a signature atrocity of twentieth century warfare. But war atrocities were not unique to Japan.

American War Atrocities: Civilian Bombing, State Terror and International Law

Throughout the long twentieth century, and particularly since World War II, the inexorable advance of weapons technology has gone hand-in-hand with international efforts to place limits on killing and the barbarism associated with war, notably indiscriminate bombing raids and other attacks directed against civilians. Advances in international law have provided important points of reference for establishing international governance norms and for inspiring and guiding social movements seeking to control the ravages of war and advance the cause of world peace.

In the following sections I consider the conduct of US warfare from the perspective of the emerging norms. In light of these norms, international criticism has long centered on German and Japanese atrocities, notably the Holocaust and specific atrocities including the Nanjing Massacre, the comfort women and the bio-warfare conducted by Unit 731. Rarely has the United States been systematically criticized, still less punished, for war atrocities. Its actions, notably the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and its conduct of the Indochina Wars prompted international controversy. [14] However, It has never been required to change the fundamental character of the wars it wages, to engage in self-criticism at the level of state or people, or to pay reparations to other nations or to individual victims of war atrocities.

While the strategic impact and ethical implications of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have generated a vast contentious literature, US destruction of more than sixty Japanese cities prior to Hiroshima has until recently been slighted both in the scholarly literatures in English and Japanese, and in popular consciousness in Japan, the US, and globally. [15]

Germany, England and Japan led the way in what is euphemistically known as “area bombing”, the targeting for destruction of entire cities with conventional weapons. From 1932 to the early years of World War II, the United States repeatedly criticized the bombing of cities. President Franklin Roosevelt appealed to the warring nations in 1939 on the first day of World War II, “under no circumstances [to] undertake the bombardment from the air of civilian populations or of unfortified cities.” [16] After Pearl Harbor, the US continued to claim the moral high ground by abjuring civilian bombing. This stance was consistent with the prevailing Air Force view that the most efficient bombing strategies were those that pinpointed destruction of enemy forces and strategic installations, not those designed to terrorize or kill noncombatants.

Nevertheless, the US collaborated with Britain in indiscriminate bombing at Casablanca in 1943. While the British sought to destroy entire cities, the Americans continued to target military and industrial sites. On February 13-14, 1945, British bombers followed by US planes destroyed Dresden, a historic cultural center with no significant military industry or bases. By conservative estimate, 35,000 people were incinerated in that single raid. [17]

But it was in Japan, in the final six months of the war, that the US deployed air power in a campaign to burn whole cities to the ground and terrorize, incapacitate, and kill their largely defenseless residents, in order to force surrender. In those months the American way of war, with the bombing of cities at its center, was set in place.

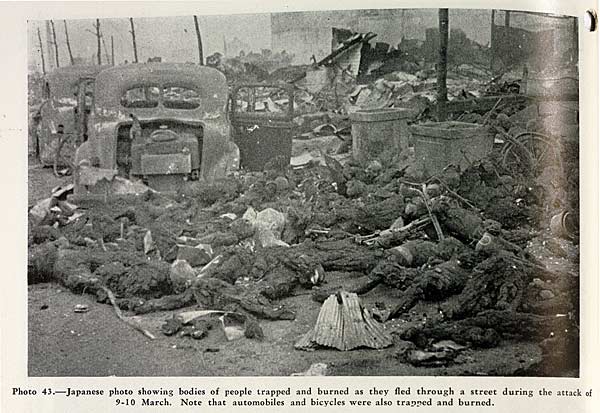

Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay, appointed commander of the 21st Bomber Command in the Pacific on January 20, 1945, became the primary architect, a strategic innovator, and most quotable spokesman for the US policy of putting enemy cities to the torch. The full fury of firebombing was first unleashed on the night of March 9-10, 1945 when LeMay sent 334 B-29s low over Tokyo, unloading 496,000 incendiaries in that single raid. Their mission was to reduce the city to rubble, kill its citizens, and instill terror in the survivors. The attack on an area that the US Strategic Bombing Survey estimated to be 84.7 percent residential succeeded beyond the planners’ wildest dreams. Whipped by fierce winds, flames detonated by the bombs leaped across a fifteen-square-mile area of Tokyo generating immense firestorms.

How many people died on the night of March 9-10, in what flight commander Gen. Thomas Power termed “the greatest single disaster incurred by any enemy in military history?” The figure of roughly 100,000 deaths and one million homes destroyed, provided by Japanese and American authorities may understate the destruction, given the population density, wind conditions, and survivors’ accounts. [18] An estimated 1.5 million people lived in the burned out areas. Given a near total inability to fight fires of the magnitude and speed produced by the bombs, casualties could have been several times higher than these estimates. The figure of 100,000 deaths in Tokyo may be compared with total US casualties in the four years of the Pacific War—103,000—and Japanese war casualties of more than three million.

Police photographer Ishikawa Toyo’s closeup of Tokyo after the firebombing

Following the Tokyo raid of March 9-10, the US extended firebombing nationwide. In the ten-day period beginning on March 9, 9,373 tons of bombs destroyed 31 square miles of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe. Overall, bombing strikes pulverized 40 percent of the 66 Japanese cities targeted. [19]

Many more (primarily civilians) died in the firebombing of Japanese cities than in Hiroshima (140,000 by the end of 1945) and Nagasaki (70,000). The bombing was driven not only by a belief that it could end the war but also, as Max Hastings shows, by the attempt by the Air Force to claim credit for the US victory, and to redeem the enormous costs of developing and producing thousands of B-29s and the $2 billion cost of the atomic bomb. [20]

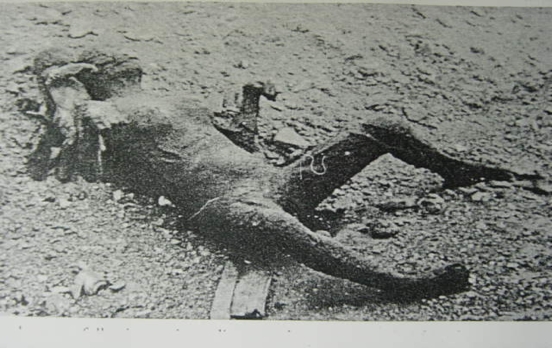

Ishikawa Toyo. A child’s corpse in the Tokyo bombing

The most important way in which World War II shaped the moral and tenor of mass destruction was the erosion of the stigma associated with the targeting of civilian populations from the air. If area bombing remained controversial throughout much of World War II, something to be concealed or denied by its practitioners, by the end of the war, with the enormous increase in destructive power of bombing, it had become the centerpiece of US war making, and therefore the international norm. [21] This approach to the destruction of cities, which was perfected in 1944-45, melded technological predominance with minimization of US casualties to produce overwhelming “kill ratios”.

The USAAF offered this ecstatic assessment of LeMay’s missions claiming that the firebombing and atomic bombing secured US victory and averted a costly land battle: [22]

In its climactic five months of jellied fire attacks, the vaunted Twentieth killed outright 310,000 Japanese, injured 412,000 more, and rendered 9,200,000 homeless . . . Never in the history of war had such colossal devastation been visited on an enemy at so slight a cost to the conqueror . . . The 1945 application of American Power, so destructive and concentrated as to cremate 65 Japanese cities in five months, forced an enemy’s surrender without land invasion for the first time in military history. . . . Very long range air power gained victory, decisive and complete.

This triumphalist (and flawed) account, which exaggerated the efficacy of air power and ignored the critical importance of sea power, the Soviet attack on Japan, and US softening of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration to guarantee the security of Hirohito, would not only deeply inflect American remembrance of victory in the Pacific War, it would profoundly shape the conduct of all subsequent American wars.

How should we compare the Nanjing Massacre and the bombing of cities? The Nanjing Massacre involved face-to-face slaughter of civilians and captured soldiers. By contrast, in US bombing of cities technological annihilation from the air distanced victim from assailant. [23] Yet it is worth reflecting on the common elements. Most notably, mass slaughter of civilians.

Why have only the atrocities of Japan at Nanjing and elsewhere drawn consistent international condemnation and vigorous debate, despite the fact that the US likewise engaged—and continues to engage—in mass slaughter of civilians in violation both of international law and ethics?

American War Crimes and the Problem of Impunity

Victory in World War II propelled the US to a hegemonic position globally. It also gave it, together with its allies, authority to define and punish war crimes committed by vanquished nations. This privileged position was and remains a major obstacle to a thoroughgoing reassessment of the American conduct of World War II and subsequent wars.

The logical starting point for such an investigation is reexamination of the systematic bombing of civilians in Japanese cities. Only by engaging the issues raised by such a reexamination—from which Americans were explicitly shielded by judges during the Tokyo Tribunals—is it possible to begin to approach the Nuremberg ideal, which holds victors as well as vanquished to the same standard with respect to crimes against humanity, or the yardstick of the 1949 Geneva Accord, which mandates the protection of all civilians in time of war. This is the principle of universality proclaimed at Nuremberg and violated in practice by the US ever since.

Every US president from Franklin D. Roosevelt to George W. Bush has endorsed in practice an approach to warfare that targets entire populations for annihilation, one that eliminates all vestiges of distinction between combatant and noncombatant. The centrality of the use of air power to target civilian populations runs like a red line from the US bombings of Germany and Japan 1944-45 through the Korean and Indochinese wars to the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan and Iraq wars. [24]

In the course of three years, US/UN forces in Korea flew 1,040,708 sorties and dropped 386,037 tons of bombs and 32,357 tons of napalm. Counting all types of airborne ordnance, including rockets and machine-gun ammunition, the total comes to 698,000 tons. Using UN data, Marilyn Young estimates the death toll in Korea, mostly noncombatants, at two to four million. [25]

Three examples from the Indochina War illustrate the nature of US bombing of civilians. In a burst of anger on Dec. 9, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon railed at what he saw as the Air Force’s lackluster bombing campaign in Cambodia. “I want them to hit everything. I want them to use the big planes, the small planes, everything they can that will help out there, and let’s start giving them a little shock.” Kissinger relayed the order: “A massive bombing campaign in Cambodia. Anything that flies on anything that moves.” [26] In the course of the Vietnam War, the US also embraced cluster bombs and chemical and biological weapons of mass destruction as integral parts of its arsenal.

An important US strategic development of the Indochina War was the extension of the arc of civilian bombing from cities to the countryside. In addition to firebombs and cluster bombs, the US introduced Agent Orange (chemical defoliation), which not only eliminated the forest cover, but exacted a heavy long-term toll on the local population including large-scale intergenerational damage in the form of birth defects. [27]

In Iraq, the US military, while continuing to pursue massive bombing of neighborhoods in Fallujah, Baghdad and elsewhere, has thrown a cloak of silence over the air war. While the media has averted its eyes and cameras, air power remains among the major causes of death, destruction, dislocation and division in contemporary Iraq. [28]The war had taken approximately 655,000 lives by the summer of 2006 and close to twice that number by the fall of 2007, according to the most authoritative study to date, that of The Lancet. Air war has also played a major part in creating the world’s most acute refugee problem. By early 2006 the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 1.7 million Iraqis had fled the country while approximately the same number were internal refugees, with the total number of refugees rising well over 4 million by 2008. [29] Nearly all of the dead and displaced are civilians.

Destroying Fallujah in order to save it

Both the plight of refugees and the intensification of aerial bombing of 2007 and 2008 have been largely invisible in the US mainstream press, This is the central reality of American state terror in Iraq. Nevertheless, despite America’s unchallenged air supremacy in Iraq since 1991, despite the creation of an array of military bases to permanently occupy that country and anchor American power in the Middle East, as the war enters its sixth year there is no end in sight to US warfare in Iraq and throughout the region. [30] Indeed, as the presidential debate makes clear, there is little prospect of exit for the US from an Iraq located at the epicenter of the world’s richest oil holdings, regardless of the outcome of the election. It is of course a region in which the geopolitical stakes far exceed those in Korea or Vietnam.

Iraqi refugees on the Syrian border

Historical Memory and the Future of the Asia Pacific

I began by considering the Nanjing Massacre’s relationship to structural and ideological foundations of Japanese colonialism and war making and US bombing of Japanese civilians in the Pacific War in 1945, and subsequently of Korean, Indochinese and Iraqi civilians. In each instance the primary focus has not been the headlined atrocity—Nanjing, Hiroshima, Nogunri, Mylai, Abu Ghraib— but the foundational practices that systematically violate international law provisions designed to protect civilians.

In both the Japanese and US cases, nationalism and national pride in the service of war and empire eased the path for war crimes perpetrated against civilian populations. In both countries, nationalism has obfuscated, even eradicated, memories of the war crimes and atrocities committed by one’s own nation, while privileging memory of the atrocities committed by adversaries. Consider, for example, American memories of the killing of 2,800 mainly Americans on September 11, 2001 compared with more than one million Iraqi deaths, millions more injured, and more than four million refugees. Heroic virtue reigns supreme in official memory and in representations such as museums, monuments, and textbooks, and often, but not always, in popular memory.

Striking differences distinguish Japanese and US responses to their respective war atrocities and war crimes. Occupied Japan looked back at the war from the midst of bombed out cities and an economy in ruins, grieving the loss of three million compatriots. But also, buoyed by postwar hopes, significant numbers of Japanese reflected on and criticized imperial Japan’s war crimes. Many embraced and continue to embrace the peace provision of the Constitution, which renounced war-making capacity for Japan. A Japan that was perpetually at war between 1895 and 1945 has not gone to war for more than six decades. It is fair to attribute this transformation in part to the widespread aversion toward war and embrace of the principles enshrined in Article 9 of the peace constitution, though it is equally necessary to factor in Japan’s position of subordination to American power and its financial and logistical support for every US war since Korea.

In the decades since 1945, the issues of war have remained alive and contentious in public memory and in the actions of the Japanese state. After the formal independence promulgated by the 1951 San Francisco Treaty, with Hirohito still on the throne, Japanese governments reaffirmed the aims of colonialism and war of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere of the1931-45 era. They released from prison and restored the reputations of former war criminals, making possible the election of Kishi Nobusuke as Prime Minister (and subsequently his grandson Abe Shinzo). In 1955, when the Liberal Democratic Party inaugurated its nearly forty-year grip on power, the Ministry of Education, tried to force authors of textbooks to downplay or omit altogether reference to the Nanjing Massacre, the comfort women, Unit 731, and military-coerced suicides of Okinawan citizens during the Battle of Okinawa. Yet these official efforts, then and since, have never gone unchallenged by the victims, by historians, or by peace activists.

From the early 1980s, memory controversies over textbook treatments of colonialism and war precipitated international disputes with China and Korea as well as in Okinawa. In Japan, conservative governments backed by neonationalist groups clashed with citizens and scholars who embraced criticism of Japan’s war crimes and supported the peace constitution. [31]

In contrast to this half-century debate within Japan, not only the US government but also most Americans remain oblivious to the war atrocities committed by US forces as outlined above. The exceptions are important. Investigative reporting revealing atrocities such as the massacres at Nogunri in Korea and My Lai in Vietnam, and torture at Abu Ghraib Prison in Iraq and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, have convinced most Americans that these events took place. Yet, precisely as presented in the official story and reiterated in the press, most of them see these as aberrant crimes committed by a handful of low-ranking officers and enlisted men. In each case, prosecution and sentencing burnished the image of American justice. The embedded structure of violence, the strategic thinking that lay behind the specific incident, and the responsibility for the atrocities committed up the chain of command, were silenced or ignored.

Two exceptions to the lack of reflection and resistance to apology provide perspective on American complacency about its conduct of wars. President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which offered apologies and reparations to survivors among the 110,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans who had been interned by the US government in the years 1942-45. Then, in 1993 on the one hundredth anniversary of the US overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, President Bill Clinton offered an apology (but no recompense) to native Hawai’ans. In both cases, the crucial fact is that the victims’ descendants are American citizens and apologies proved to be good politics for the incumbent. [32]

One additional quasi-apology bears mention. In March 1999, Clinton, speaking in Guatemala City of the US role in the killing of 200,000 Guatemalans over previous decades, made this statement: “For the United States, it is important that I state clearly that support for military forces and intelligence units which engaged in violence and widespread repression was wrong and the United States must not repeat that mistake.” The remarks had a certain political significance at the time, yet they had more of the weight of a feather than of Mt. Tai. No word of apology was included. No remuneration was made to victims. And, above all, the United States did not act to end its violent interventions in scores of countries in Latin America, Asia or elsewhere. [33]

There have of course been no apologies or reparations for US firebombing or atomic bombing of Japan, or for killing millions and creating vast numbers of refugees in Korea, Vietnam or Iraq, or for US interventions in scores of other ongoing conflicts in the Americas and Asia. Such is the prerogative of impunity of the world’s most powerful nation. [34]

However, there has been one important act of recognition of the systemic character of American atrocities in Vietnam, and subsequently in Iraq. Just as Japanese troops provided the most compelling testimony on Japanese wartime atrocities, it is American veterans whose testimony most effectively unmasked the deep structure of the American way of war in Vietnam and Iraq.

In the Winter Soldier investigation in Detroit on January 31 to February 2, 1971, Vietnam Veterans Against the War organized testimony by 109 discharged veterans and 16 civilians. John Kerry, later a US Senator and presidential candidate testified two months later in hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee as representative of the Winter Soldier event. Kerry summed up the testimony: [35]

They had personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks, and generally ravaged the countryside of South Vietnam. . .”

Kerry continued: “We rationalized destroying villages in order to save them . . . . We learned the meaning of free fire zones, shooting anything that moves, and we watched while America placed a cheapness on the lives of orientals.”

On March 13-16, 2008 a second Winter Soldier gathering took place in Washington DC, with hundreds of Iraq War veterans providing testimony, photographs and videos documenting brutality, torture and murder in cases such as the Haditha Massacre and the Abu Ghraib torture. [36] As in the first Winter Soldier, the mainstream media ignored the event organized by Iraq Veterans Against War. Again, however, the voices of these veterans have reached out to some through films and new electronic and broadcast media such as YouTube.

IVAW prepare for Winter Soldier 2008

The importance of apology and reparations lies in the fact that through processes of recognition of wrongdoing and efforts to make amends (however belated or inadequate) to victims, the poisonous legacies of war and colonialism may be alleviated or overcome and foundations laid for a harmonious future. In Germany, this involved renunciation of Nazism, the formation of a new government distinctive from and critical of the former government; consensus expressed in the nation’s textbooks and curricula critical of Nazi genocide and aggression; monuments and museums commemorating the victims; and payment of substantial reparations to individual victims (albeit under US pressure). All of these actions paved the way for Germany’s reemergence at the center of the European Union.

In contrast to their German counterparts, Japanese and American leaders have strongly resisted apology and reparations. While many Japanese people have reflected deeply on their nation’s war atrocities, Japanese leaders, sheltered from Asia by the US-Japan security relationship, had little incentive to reflect deeply on the nation’s wartime record in China or elsewhere. Americans, for their part, have felt little pressure either domestic or international to apologize or provide reparations to victims from other nations.

Material foundations for a breakthrough in international relations in the Asia Pacific exist in the booming economic, financial, and trade ties across the region. In particular, strong links exist among Japan, China and South Korea, each of which are among the others’ first or second leading trade and investment partners. Nor is the opening limited to economics. Equally notable are burgeoning cultural relations. For example, “the Korean wave” in TV and film is taking China, Japan and parts of Southeast Asia by storm. Japanese manga, anime and TV dramas are widely disseminated throughout the Asia Pacific. [37] Similarly, Chinese pop music and TV dramas also span the region, particularly, but not exclusively, where overseas Chinese are numerous. In addition, Pan-Asian collaborations in film, anime, and music are widespread. Such cultural interpenetration has not waited for political accommodation. Indeed, it has proceeded apace even during times when Japan-Korea and Japan-China tensions over territorial and historical memory issues are high. And for the first time, we can see in the six-party talks on North Korean nuclear weapons and the possibility of an end to Cold War divisions, possibilities for the emergence of a regional framework.

It has been widely recognized that a major obstacle to the emergence of a harmonious order in the Asia Pacific is the politics of denial of atrocities associated with war and empire. China, Korea and other former victims of Japanese invasion and colonization have repeatedly criticized Japan. [38] Largely ignored in debates over the future of the Asia Pacific has been the responsibility of the US to recognize and provide reparations for its own numerous war atrocities as detailed above, notably in the bombing of Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese and Iraqi civilians.

Such responsible actions by the world’s most powerful nation would make it possible to bring to closure unresolved war issues both for the many individual victims of US bombing and other atrocities, and the continued hostilities between states, above all the US-North Korea conflict and the division of the two Koreas. It would also pave the way for a Japan that remains within the American embrace to acknowledge and recompense victims of its own war crimes. Might it not help pave the way for an end to US wars without end across the Asia Pacific and beyond?

Mark Selden is a coordinator of Japan Focus and a research associate in the East Asia Program at Cornell University.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on April 15, 2008.

Notes

[*] I am indebted to Herbert Bix, Richard Falk, and especially Laura Hein for criticism and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper. This is a revised and expanded version of a talk delivered on December 15, 2007 at the Tokyo International Symposium to Commemorate the Seventieth Anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre.

[1] Most discussion of historical memory issues has centered on the Japan-China and the Japan-Korea relationships. However, the controversy that erupted in 2007 over the US congressional resolution calling on Japan to formally apologize and provide compensation for the former comfort women illustrates the ways in which the US-Japan relationship is also at stake. Kinue Tokudome, “Passage of H.Res. 121 on ‘Comfort Women’, the US Congress and Historical Memory in Japan,” Japan Focus. Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “Japan’s ‘Comfort Women’: It’s time for the truth (in the ordinary, everyday sense of the word),” Japan Focus.

[2] Fierce debate continues among historians, activists and nations over the number of victims. The issue involves differences over both the temporal and spatial definition of the massacre. The official Chinese claim inscribed on the Nanjing Massacre Memorial is that 300,000 were killed. The most careful attempts to record the numbers by Japanese historians, which include deaths of civilians and soldiers during the march from Shanghai to Nanjing as well as deaths following the capture of the capital suggest numbers in the 80,000 to 200,000 range. In recent years, the first serious Chinese research examining the massacre, built on 55 volumes of documents, has begun to appear. See Kasahara Tokushi, Nankin Jiken Ronsoshi. Nihonjin wa shijitsu o do ninshiki shite kita ka? (The Nanjing Incident Debate. How Have Japanese Understood the Historical Evidence?) (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 2007) for the changing contours of the Japanese debate over the decades. Kasahara Tokushi and Daqing Yang explore “The Nanjing Incident in World History,” (Sekaishi no naka no Nankin Jiken) in a discussion in Ronza, January, 2008, 184-95, ranging widely across international and joint research and the importance of new documentation from the 1970s to the present. Reiji Yoshida and Jun Hongo, “Nanjing Massacre: Toll will elude certitude. Casualty counts mirror nations’ extremes, and flexibility by both sides in middle,” Japan Times, Dec 13, 2007.

[3] I first addressed these issues in Laura Hein and Mark Selden, eds., Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, China and the United States (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 2000).

[4] For discussion of the international legal issues and definition of state terrorism see the introduction and chapter two of Mark Selden and Alvin So, eds., War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), pp. 1-40. See also Richard Falk’s chapter in that volume, “State Terror versus Humanitarian Law,” pp. 41-62.

[5] The following discussion of the Nanjing Massacre and its antecedents draws heavily on the diverse contributions to Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, ed., The Nanking Atrocity 1937-38: Complicating the Picture (New York and London: Berghahn Books, 2007) and particularly the chapter by the late Fujiwara Akira, “The Nanking Atrocity: An Interpretive Overview,” available in a revised version at Japan Focus. Wakabayashi, dates the start of the “Nanjing atrocity”, as he styles it, to Japanese bombing of Nanjing by the imperial navy on August 15. “The Messiness of Historical Reality”, p. 15. Chapters in the Wakabayashi volume closely examine and refute the exaggerated claims not only of official Chinese historiography and Japanese deniers, but also of progressive critics of the massacre. While recognizing legitimate points in the arguments of all of these, the work is devastating toward the deniers who hew to their mantra in the face of overwhelming evidence, e.g. p. 143.

[6] Utsumi Aiko, “Japanese Racism, War, and the POW Experience,” in Mark Selden and Alvin So, eds., War and State Terrorism, pp. 119-42.

[7] Presentation at the Tokyo International Symposium to Commemorate the Seventieth Anniversary of the Nanjing Massacre, December 15, 2007.

[8] Yang Daqing, “Atrocities in Nanjing: Searching for Explanations,” in Diana Lary and Stephen MacKinnon, eds., Scars of War. The Impact of Warfare on Modern China (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2001), pp. 76-97.

[9] The signature statement was that of George W. Bush on March 19, 2003: “My fellow citizens, at this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger… My fellow citizens, the dangers to our country and the world will be overcome. We will pass through this time of peril and carry on the work of peace. We will defend our freedom. We will bring freedom to others and we will prevail.”

[10] Timothy Brook, Collaboration: Japanese Agents and Local Elites in Wartime China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2005).

[11] Tsuneishi Keiichi, “Unit 731 and the Japanese Imperial Army’s Biological Warfare Program,” John Junkerman trans., Japan Focus.

[12] Mark Selden, China in Revolution: The Yenan Way Revisited (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1995); Chen Yung-fa, Making Revolution: The Chinese Communist Revolution in Eastern and Central China, 1937-1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986); Edward Friedman, Paul G. Pickowicz and Mark Selden, Chinese Village, Socialist State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991); Chalmers Johnson, Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power: The Emergence of Revolutionary China (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962). In carrying out a reign of terror in resistance base areas Japanese forces anticipated many of the strategic approaches that the US would later apply in Vietnam. For example, Japanese forces pioneered in constructing “strategic hamlets” involving relocation of rural people, torching of entire resistance villages, terrorizing the local population, and imposing heavy taxation and labor burdens.

[13] Yuki Tanaka, Japan’s comfort women: sexual slavery and prostitution during World War II and the US occupation (London ; New York : Routledge, 2002). This systematic atrocity against women has haunted Japan since the 1980s when the first former comfort women broke silence and began public testimony. The Japanese government eventually responded to international protest by recognizing the atrocities committed under the comfort woman system, while denying official and military responsibility. It established a government-supported but ostensibly private Asian Women’s Fund to apologize and pay reparations to former comfort women, many of whom rejected the terms of a private settlement. See Alexis Dudden and Kozo Yamaguchi, “Abe’s Violent Denial: Japan’s Prime Minister and the ‘Comfort Women,’” Japan Focus. See Wada Haruki, “The Comfort Women, the Asian Women’s Fund and the Digital Museum,” Japan Focus

for Japanese and English discussion and documents archived at the website.

[14] Peter J. Kuznick, “The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative,” Japan Focus.

[15] Early works that drew attention to US war atrocities often centered on the torture, killing and desecration of the remains of captured Japanese soldiers are Peter Schrijvers, The GI War Against Japan. American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific During World War II (New York: NYU Press, 2002) and John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon, 1986). The Wartime Journals of Charles Lindbergh (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1970) is seminal in disclosing atrocities committed against Japanese POWs. A growing literature has begun to examine U.S. bombing policies. A. C. Grayling, Among the Dead Cities, provides a thorough assessment of US and British strategic bombing (including atomic bombing) through the lenses of ethics and international law. Grayling concludes that the US and British killing of noncombatants “did in fact involve the commission of wrongs” on a very large scale. Pp. 5-6; 276-77. See Herbert P. Bix, “War Crimes Law and American Wars in 20th Century Asia,” Hitotsubashi Journal of Social Studies, Vol. 33, No. 1 (July 2001), pp. 119-132.

[16] Quoted in Sven Lindqvist, A History of Bombing (New York: New Press, 2000), p. 81. The US debate over the bombing of cities is detailed in Michael Sherry, The Rise of American Air Power: The Creation of Armageddon (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1987), pp. 23-28, pp. 57-59. Ronald Schaffer, Wings of Judgment: American Bombing in World War II (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), pp. 20-30, I08-9; and Sahr Conway-Lanz, Collateral Damage, Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity After World War II (London: Routledge, 2006). p. 10. For a more detailed account of US bombing see Mark Selden, A Forgotten Holocaust: US Bombing Strategy, the Destruction of Japanese Cities and the American Way of War from the Pacific War to Iraq,” Japan Focus.

[17] Sherry, Air Power, p. 260. With much U.S. bombing already relying on radar, the distinction between tactical and strategic bombing had long been violated in practice. The top brass, from George Marshall to Air Force chief Henry Arnold to Dwight Eisenhower, had all earlier given tacit approval for area bombing, yet no orders from on high spelled out a new bombing strategy.

[18] The Committee for the Compilation of Materials on Damage Caused by the Atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Physical, Medical and Social Effects of the Atomic Bombing (New York: Basic Books, 1991), pp. 420-21; Cf. U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, Field Report Covering Air Raid Protection and Allied Subjects Tokyo (n.p. 1946), pp. 3, 79; The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey study of Effects of Air Attack on Urban Complex Tokyo-Kawasaki-Yokohama (n.p. 1947). In contrast to the vast survivor testimony on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in addition to poems, short stories, novels, manga, anime and film documenting the atomic bombing, the testimony for the firebombing of Tokyo and other cities is sparse. Max Hastings provides valuable first person accounts of the Tokyo bombing based on survivor recollection. Retribution. The Battle for Japan 1944-45 (New York: Knopf, 2008), pp. 297-306.

[19] All but five cities of any size were destroyed. Of these cities, four were designated atomic bomb targets, while Kyoto, was spared. John W. Dower, “Sensational Rumors, Seditious Graffiti, and the Nightmares of the Thought Police,” in Japan in War and Peace (New York: The New Press, 1993), p. 117. United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report, Vol I, pp. 16-20.

[20] Retribution, pp. 296-97. Hastings, p. 318, makes a compelling case that the Japanese surrender owed most to the naval blockade which isolated Japan and denied it access to the oil, steel and much more in severing the links to the empire.

[21] The horror felt round the world at the German bombing at Guernica, Japanese bombing of Shanghai and Chongqing, and the British bombing of Dresden would not be felt so intensely and universally ever again, regardless of the scale of bombing in Korea, Vietnam or Iraq . . . with the possible exception of the outpouring of sympathy for the 2,800 victims of the 9/11 terror bombing of the New York World Trade Center.

[22] “Postwar Narrative,” quoted in Hastings, Retribution, p. 317.

[23] Another important factor is the difference in the character of the two wars. Japan’s invasion of China involved very different dynamics from the US-Japan conflict between two expansionist powers. The present article does not explore this issue.

[24] In practice. Sahr Conway-Lanz provides the definitive study of the “collateral damage” argument that has been repeatedly used to deny deliberate killing of civilians in US bombing. Collateral Damage, Americans, Noncombatant Immunity, and Atrocity After World War II.

[25] Marilyn Young, “Total War,” forthcoming chapter in Bombing Civilians, Marilyn Young and Yuki Tanaka eds. (New York: The New Press).

[26] Elizabeth Becker, “Kissinger Tapes Describe Crises, War and Stark Photos of Abuse,” The New York Times, May 27, 2004.

[27] Seymour Hersh, Chemical and Biological Warfare (New York: Anchor Books,1969), pp. 131-33. Hersh notes that the $60 million worth of defoliants and herbicides in the 1967 Pentagon budget would have been sufficient to defoliate 3.6 million acres if all were used optimally.

[28] In contrast to the Vietnam War in particular, in which critical journalism in major media eventually played a powerful role in fueling and reinforcing the antiwar movement, the major print and broadcasting media in the Iraq War have dutifully averted their eyes from the air war in deference to the Bush administration’s wishes. On the air war, see, for example, Seymour Hersh, “Up in the Air. Where is the Iraq war headed next?” The New Yorker, Dec 5, 2005; Dahr Jamail, “Living Under the Bombs,” TomDispatch, February 2, 2005; Michael Schwartz, “A Formula for Slaughter. The American Rules of Engagement from the Air,” TomDispatch, January 14, 2005; Nick Turse, America’s Secret Air War in Iraq, TomDispatch, February 7, 2007; Tom Engelhardt, “9 Propositions on the U.S. Air War for Terror,” TomDispatch, April 8, 2008. The invisibility of the air war is nicely revealed in conducting a Google search for “Iraq War” and “Air War in Iraq”. The former produces numerous references to the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, Wikipedia and a wide range of powerful media. The latter produces references almost exclusively to blogs and critical sources such as those cited in this note.

[29] Sabrina Tavernese, “For Iraqis, Exodus to Syria, Jordan Continues,” New York Times, June 14, 2006. Michael Schwartz, “Iraq’s Tidal Wave of Misery. The First History of the Planet’s Worst Refugee Crisis”, TomDispatch, February 10, 2008. The UN estimates that there are 1.25 million Iraqi refugees in Syria and 500,000 in Jordan, 200,000 throughout the Gulf states, 100,000 more in Europe. The United States accepted 463 refugees between the start of the war in 2003 and mid-2007. The International Organization for Migration estimated the displacement rate throughout 2006-07 at 60,000 per month, with the American “surge” accelerating displacement, already more than one in seven Iraqis a nation of 28 million people have been displaced.

[30] Anthony Arnove, “Four Years Later… And Counting. Billboarding the Iraqi Disaster”, TomDispatch, March 18, 2007. Seymour Hersh, “The Redirection. Is the Administration’s new policy benefiting our enemies in the war on terrorism?” The New Yorker March 3, 2007. Michael Schwartz, “Baghdad Surges into Hell. First Results from the President’s Offensive”, TomDispatch, February 12, 2007.

[31] Mark Selden, “Nationalism, Historical Memory and Contemporary Conflicts in the Asia Pacific: the Yasukuni Phenomenon, Japan, and the United States” Japan Focus; Yoshiko Nozaki and Mark Selden, “Historical Memory, International Conflict and Japanese Textbook Controversies in Three Epochs,” forthcoming Contexts: The Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society, Vol I, Number 1; Takashi Yoshida, “Revising the Past, Complicating the Future: The Yushukan War Museum in Modern Japanese History,” Japan Focus; Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka, “Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States,” Japan Focus; Aniya Masaaki, “Compulsory Mass Suicide, the Battle of Okinawa, and Japan’s Textbook Controversy,” Japan Focus.

[32] Thanks to Laura Hein for suggesting the framing of this issue. On the Reagan decision, reparations and the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, see

Mitchell T Maki, Harry H Kitano, and S Megan Berthold, Achieving the Impossible Dream: How Japanese Americans Obtained Redress (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1999); see also the following and Clinton’s apology to Hawaiians took the form of Public Law 103-150. The formal apology recognized the devastating effects of subsequent social changes on the Hawaiian people and looked to reconciliation. But offered no reparations or other specific measures to alleviate the sufferings caused by US actions.

[33] Emily Rosenberg drew my attention to the Guatemala quasi-apology. Clinton’s remarks were prompted by the February 1999 publication of the findings of the independent Historical Clarification Commission which concluded that the US was responsible for most of the human rights abuses committed during the 36-year war in which 200,000 died. Martin Kettle and Jeremy Lennard, “Clinton Apology to Guatemala,” The Guardian, March 12, 1999. Mark Weisbrot, “Clinton’s Apology to Guatemala is a Necessary First Step,” March 15, 1999, Knight-Ridder/Tribune Media Services.

[34] How are we to define power? If no nation remotely rivals American military power, particularly in the wake of the demise of the Soviet Union, if the United States military budget in 2008 is larger than that of all other nations combined — before counting the special appropriations for wars in Iraq and Afghanistan — the striking fact is that the US has fought to stalemate or defeat in each of the major wars it has entered since World War II.

[35] Kerry’s testimony, ignored by the mass media but made available through film and other media, is available here.

[36] See the testimony and the historical record here and here .

[38] We have underlined the deleterious effects of Japanese nationalism in preventing recognition and apology for atrocities. Reconciliation is made more difficult by exaggerated claims with respect to the Nanjing Massacre by nationalists in China and the Chinese diaspora.