Japan’s Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Stumbles on ‘Baby Machines’

By Mark Schreiber

On January 27, at a gathering of Liberal Democratic Party supporters in Matsue City, Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare Yanagisawa Hakuo made his now-famous remark that “women are child-bearing machines,” and immediate plunged himself into water considerably hotter than any of the local onsen.

“I was just trying to make the subject easier to understand,” Yanagisawa was said to have muttered afterward.

Harrumph! Easy for whom? Most likely for himself.

Serving as a “judge,” trying this case for Aera (Feb. 12), female literary critic Saito Minako observed that insensitive remarks by politicians seem to pop up somewhere almost once a week. It’s like cockroaches in the kitchen: encounter one, and you can assume 100 others are lurking under the sink.

The issue is a hot potato, and Ms. Saito opines that politicians would best be advised to say nothing at all. Or, if obliged to say something, at least describe the issue in more civil terms, like “These days, women don’t feel inclined to give birth.”

Mr. Yanagisawa spent most of his career as a bureaucrat before turning to politics, and his constituents view him as something of a bumbler at the podium, spouting numbers or logic that often fail to connect.

“More than intending to show contempt for women, I think his remark reveals the true feelings of a Ministry of Finance bureaucrat,” political commentator Suzuki Toichi tells Sunday Mainichi (Feb. 18). “He sees increasing the population only in terms of expanding the tax base.”

Shukan Asahi (Feb. 16) features none other than Yanagisawa Noriko, a woodblock print artist and professor at

“Why did you make that stupid remark?” she admonished her husband.

“Sorry, sorry!” came his reply.

Yanagisawa was the sixth of eight children in a poor family. From middle through high school he delivered newspapers and performed other chores to help make ends meet.

“If his mother were alive today, she might tell him, ‘I don’t remember bringing you up to be the kind of person who would say something like that,'” she remarks.

“This November we’ll have been married for 42 years,” Noriko continues. “There are times when I feel more like his mother than his wife. A machine might have a memory, but it doesn’t have a heart. Women give birth with their hearts — now more than ever. I’m going to remind him of this.”

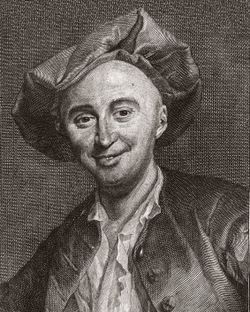

Writing in Shukan Gendai (Feb. 17), novelist and academic Takahashi Genichiro points out that Yanagisawa’s observation was neither original nor contemporary. To support this contention, he cites 18th century French philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-1751) who authored the controversial work “L’Homme machine (Man a Machine).”

La Mettrie had contended against the existence of the human soul, a view that got him expelled from one European country after another.

Takahashi’s mother once told him, that on the day after her wedding, her mother-in-law (Takahashi’s paternal grandmother) coldly informed her, “You were brought into the Takahashi household to bear children. We are merely leasing your womb.”

What an absolutely terrible thing to say to a bride of one day! But perhaps, Takahashi reflects, not really so different in substance from Mr. Yanagisawa’s remarks — except perhaps more close up and personal. Half a century ago that was the way many mothers-in-law viewed the matter.

But, Takahashi, points out, consider the soldiers

Children attending a cram school in Japan.

When these children come of age, they are “installed” as “new model” machines in companies, where they’ll be spending the next 40 years, until the time comes for them to be automatically discarded. Even though still usable, they will have become obsolete and therefore useless, at which time they’ll be placed beside the window and ignored.

As a youth, Takahashi used to revel in the “Astro Boy” comics by cartoonist Tezuka Osamu. How, Takahashi would marvel, did Astro Boy, being a machine, come to possess such a valiant spirit? But now he understands: the humans depicted in Astro Boy’s proximity were actually all machines as well.

Mark Schreiber is the “

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The