Victims of Colonialism? Japanese Agrarian Settlers in Manchukuo and Their Repatriation

Mariko Asano TAMANOI

Manchukuo is the state that Japan created in Northeast China (Manchuria) in 1932 to serve its interests. To populate this vast overseas empire with Japanese, the government sent approximately 380,000 farmers and their families as “agrarian immigrants (nogyo imin).” Many of them were victims of the depression at home. By participating in the construction of Manchukuo, they joined the circle of “colonizers”: they received large tracts of land which the Japanese military had confiscated from Chinese farmers. Their life as settlers, however, was by no means easy. Many did not know what to plant or how to till the land. When they hired Chinese agricultural laborers,” many tensions arose. The settlers’ relations with more than six hundred thousand Korean rice-cultivating farmers, who also settled in Manchuria in the 1930s, were also fraught.

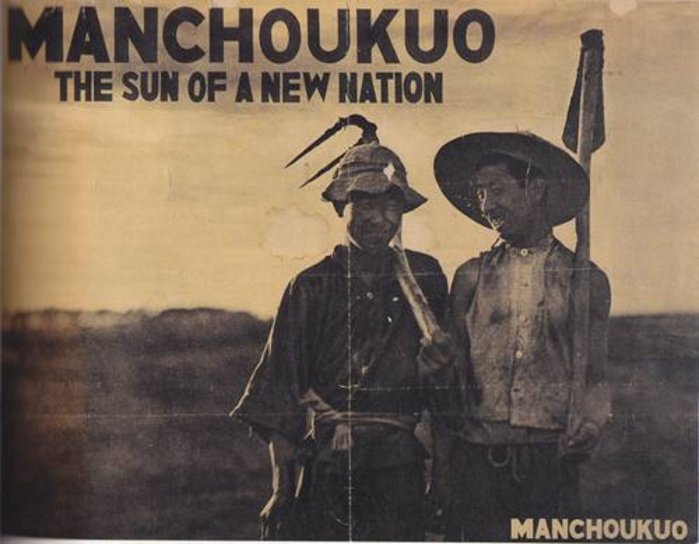

Poster of Manchukuo created by the Manchukuo Government for the Western audience, featuring a couple of Japanese agrarian immigrants.

After the onset of the Japan-China War (1937-1945) and the Pacific War (1941-1945), male agrarian settlers were inducted into the military and sent to fight further south in China or Southeast Asia, leaving behind women, children, and the elderly in northern Manchuria near the Soviet border.

Postcard published by the South Manchurian Railway Company, featuring a Japanese agrarian immigrant.

When the Soviets invaded Manchuria on August 9, 1945, these unprotected civilians were abandoned by fleeing Japanese forces and became easy targets for attack. Many of those who eluded the fighting died of disease, malnutrition, and “compulsory group suicides” while seeking to return to Japan. In order to save the lives of their children as well as their own lives, thousands of mothers faced the agonizing decision, in their words, to “leave,” “give up,” “abandon,” “sell,” or “entrust” their loved ones to Chinese families.

Immigrant children at play.

These children were raised by Chinese adoptive parents, married Chinese citizens, and raised their own families in China. These Japanese-born children grew up as Chinese. They did not, or could not, return to Japan until the mid-1970s for a variety of reasons, including not only the absence of normal diplomatic relations between Japan and the People’s Republic of China prior to 1972, but also the loss of all contact with their natal families. The number of these children is said to be about 30,000.

Memory Maps: The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan is based on fieldwork conducted by the author in Nagano in central Japan, which sent some 38,000 agrarian immigrants to Manchuria, and in Tokyo where many returnees presently reside. The book presents the memories of the following groups of Japanese, Japanese-Chinese and Chinese people who participated in the Japan’s imperial project in Manchuria, and examines how those memories crisscrossed in the postwar era from 1945 to 2006:

1) Japanese men and women who immigrated to Manchuria as agrarian settlers and returned to Nagano prefecture after Japan’s defeat between 1946 and 1949 (memory map 1).

2) The children of agrarian settlers who were left behind in China after 1945. Most of them were raised by Chinese adoptive parents, married Chinese citizens, and raised families in China. Significant numbers began returning to Japan permanently in the mid-1970s. While they were expected to return to the homes of their biological parents in rural Nagano, most ended up residing in large cities as Tokyo where jobs were available (memory map 2).

3) The (Japanese-Chinese) children of the offspring of Japanese settlers in Manchuria who joined their parents in Japan in the 1980s and 90s (memory map 3).

4) Chinese who adopted children of Japanese agrarian settlers in Manchuria soon after the war’s end (memory map 4).

Maps in this book thus serve to organize, in terms of time and space, the memories of all these people. Memory map 1 is presented here. These agrarian settlers-turned-repatriates to postwar Japan were both accomplices in and victims of Japanese colonialism in Manchuria.

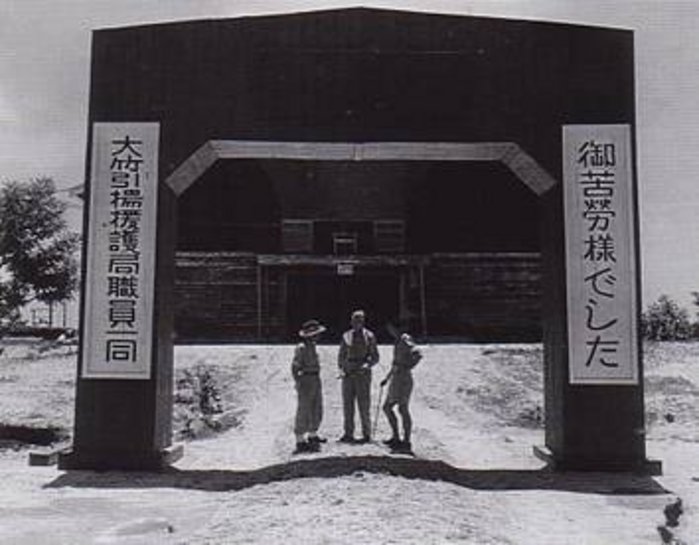

Receiving center for repatriates from Manchuria and other parts of the Empire. The poster on the right side reads: “Thank you very much for your hardship.”

Their narratives illuminate the complex and painful history of Japanese in Manchuria, illustrating the fact that no black and white picture can capture the full dimensions of the colonial experience.

Mariko Asano Tamanoi is Professor of Anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles and a Japan Focus associate. She is the author of Under the Shadow of Nationalism: Politics and Poetics of Rural Japanese Women (1998) and Memory Maps: The State and Manchuria in Postwar Japan (2008) as well as editor of Crossed Histories: Manchuria in the Age of Empire. She wrote this introduction for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Posted on February 2, 2009.

Recommended citation: Mariko Asano Tamanoi, “Victims of Colonialism? Japanese Agrarian Settlers and Their Repatriation to Japan” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 6-1-09, February 2, 2009.