Maaike Okano-Heijmans

Abstract

This paper analyzes Japan’s concerns, as well as its prioritization and leverage points, in multilateral negotiations on North Korea’s nuclear programme within the Six-Party Talks. It argues that Japan has deliberately taken an obstructionist stance in multilateral negotiations and that three issues are relevant to understanding Japan’s actions: Japan’s close relations with the US, its preference for economic rather than political diplomacy, and the dominance of single-issue politics influenced by domestic political considerations. In the Six-Party Talks, Japan has played a largely circumstantial role in the practical sense while being a powerful spoiler in broader, strategic terms. Tokyo wants a denuclearized Korean Peninsula and a stable neighbour, but a Six-Party Talks solution – which would enhance China’s standing – is in itself not a priority. Moreover, Pyongyang provides a welcome justification to the Japanese government for the enhancement of its security capabilities. Japanese interests are well served by retaining the status quo, which explains why Tokyo consciously adopted the role of spoiler. After the Bush administration removed North Korea from its list of terrorism sponsoring states, this position appears no longer sustainable.

Introduction

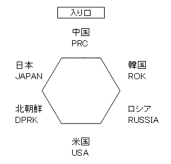

Since 2003 the Six-Party Talks have brought together North Korea, the United States, China, Japan, South Korea and Russia in comprehensive negotiations revolving around the issue of North Korea’s nuclear weapons programme. It was Japanese Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo who made the initial proposal for six-party negotiations in 1998, [1] when the Japanese government was driven by a fear of being left out of multilateral negotiations on an issue of great importance to its national security. Responses from other countries at the time were lukewarm at best, however. None of the then Four-Party Talks’ members saw immediate value in including Japan – or Russia. While supporting the four-way talks, the Japanese government used the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) as a channel to address its concerns. Only after the US claim in October 2002 that North Korea had disclosed a uranium-based nuclear programme, did the parties agree to a six-way multilateral dialogue, including Japan. [2] Japan’s participation and cooperation in the Six-Party Talks (SPT) was deemed of importance in order to reach a comprehensive deal with North Korea. [3]

Although the Japanese government has made it clear that North Korea poses the greatest threat to its national security, [4] it is not so much Pyongyang’s nuclear devices and missiles as the alleged abduction of some seventeen Japanese nationals from Japan by North Korea in the 1970s and 1980s that is the chief focus of Japanese politicians and policymakers. [5] This issue has framed the bilateral and multilateral relations with North Korea since 2002. It is also the reason for Pyongyang’s repeated calls to exclude Tokyo from the Six-Party negotiating table and other parties’ concern over a slowdown in negotiations.

The question must be asked why the Japanese government prioritizes a bilateral issue while its national and regional security at large is at stake. Japan’s successful test of its missile interceptor system in December 2007 and the deployment of anti-ballistic missile units in its capital city show that Japan – in cooperation with its closest ally, the United States – is stepping up its national defense. [6] Certainly, the North Korean threat facilitates the otherwise controversial military enhancement of Japan in a context of uncertainty about the US commitment and an increasingly stronger China. Could it be that a focus on the abductions serves to prolong the threat and justify Japan’s security policy?

Washington’s conciliatory approach in the wake of Pyongyang’s nuclear test of October 2006 left Tokyo in an awkward position. The credibility of the United States as an ally is a big concern. As Washington and Pyongyang slowly moved forward, Tokyo might in the end be forced to follow. This partly explains why the government appeared to move away from its hard-line stance, characterized by single-issue politics and sanctions. However, a majority of Japanese politicians and the public strongly opposes any softening of policy.

Economic diplomacy is an important factor in Japan’s diplomatic strategy. Focussing discussion on the political context, Tokyo’s diplomatic cards and policies of the Prime Ministers in office since the initiation of the Six-Party Talks, we argue that Japan has deliberately adopted the role of spoiler in multilateral negotiations. [7]

The Political Context and Japan’s Foreign Policy Agenda

As with any bilateral relationship, Japan’s relations with North Korea revolve around an array of international, regional, bilateral and domestic issues. More than in any other relationship, however, Japan’s options with regard to Pyongyang are limited. This is true for three important considerations: national and regional security – including the North’s nuclear and missile programme –, the abductees and the normalization of relations.

Japan’s leverage in both the bilateral and multilateral context is constrained by the fact that North Korea is above all interested in improving and developing relations with the United States, which it regards as the greatest threat to its national security. Pyongyang views Tokyo as a second tier: Washington’s little brother that needs to be seriously consulted only when deemed to its own benefit. Therefore, a key to solving the security threat that North Korea poses to Japan lies in the hands of its alliance partner.

From a US perspective, Japan’s participation in the Six-Party Talks constitutes a critical paradox, particularly after Washington adopted a more engaging stance towards Pyongyang. On the one hand, US officials admit that a deal with North Korea will need the full backing of Japan. The substantial Japanese economic aid that would become available with normalization is regarded as a key component of a comprehensive agreement. [8] At the same time, however, Washington has made it clear that it will move ahead even without an immediate solution to the abductees issue. [9] In an attempt to break the deadlock and avoid having to upset its ally when moving ahead, the United States in bilateral as well as multilateral meetings pressed North Korea to address the abductees issue with Japan.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that there is a crucial difference in the threat perception between the US and Japan. The two countries share concerns of nuclear and missile development and export of weapons of mass destruction. Nevertheless, the real threat perception in Japan is much bigger, as Tokyo seriously fears North Korean missiles, nuclear devices and flows of refugees because of its geographic proximity. Hence, anything less than a complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula is unacceptable to the Japanese government. This explains Japan’s rather lukewarm response to the February 2007 Six-Party Talks agreement, which includes a time-frame and monitoring mechanism for the declaration of nuclear programs and disablement of existing nuclear facilities, but addresses denuclearization only in vague terms. [10]

Japan’s leeway on another major issue of concern is also constrained – albeit more by its own choice. Following the negative response from the South Korean government to Japanese approaches to Pyongyang in 1990, Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki assured Seoul that Japan’s policy towards North Korea would move in line with the South-North dialogue. Japan has generally maintained this stance, especially with regard to the normalization of diplomatic relations. As in bilateral relations with other countries in the region, the burden of history looms large in talks on official relations. Reparations for wrongdoing during the colonial period and Pacific War play a vital role in discussion about the establishment of official relations between Japan and North Korea. [11]

The normalization of relations is of importance in bilateral and multilateral talks, giving Japan a diplomatic card in the Six-Party context. Financial compensation or, as the Japanese insist, ‘economic assistance’ would provide the North Korean regime with huge funds relative to the size of its economy. These billions of dollars are addressed in the multilateral context in two ways. First, normalization of Japan-North Korea relations is included as one of the goals in the SPT agreements of September 2005 and February 2007. Second, the financial stimulus constitutes a ‘carrot’ to any final comprehensive deal. During one of the SPT sessions, North Korea implied that economic aid by Japan (and South Korea) would be needed for the ultimate settlement of its nuclear programme. [12] In recent years Tokyo used this card to indirectly frustrate negotiations, thereby becoming a spoiler of the Six-Party Talks.

This obstructionist stance can be linked directly to developments in the mid-1990s, which made Japan more sensitive to threats in its security environment. The nuclear crisis of 1993-94, the launch of (test) missiles – especially, the Taepodong missile that flew over Japanese territory in 1998 – and intrusions into Japan’s territorial waters by North Korean spy boats, as well as Chinese nuclear tests induced the government to reconsider its regional and security strategy. [13] Security considerations received growing media attention and started to play a role in Japan-North Korea relations. Particularly since 2002-03 television and other forms of media directed the public into a relatively constricted range of views on North Korea through narrow, biased saturation coverage. [14] The focus of attention was the abductees issue, which became the human face of the abstract North Korean threat.

Ironically perhaps, North Korean nuclear and missile development is an opportunity in the security field, in the sense that it creates a favourable environment for stepping-up missile defense and increasing the role of the Self-Defense Forces in developments in areas surrounding Japan. From a regional perspective, the North Korean threat is thereby a welcome excuse to improve military capacities and Japan’s regional security, notably towards China.

Tokyo’s Diplomatic Cards

The funds that will become available to North Korea with the establishment of official relations with Japan are clearly a tool of Tokyo’s economic diplomacy and security strategy at large. [15] Financial and economic relations are also of significance. Here, it is clear that Japan’s leverage over Pyongyang declined with the sharp downturn in economic relations with North Korea throughout the past decade. [16] Financial flows decreased as the Japanese government in recent years hardened its policy towards the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chosen Soren in Japanese) and pachinko (gambling parlours), which are widely believed to have provided Pyongyang with significant sums of cash. By 2006 the total bilateral trade volume had declined to only one third of its 2002 level, from roughly 370 to 120 million US dollars. A mere 9 million US dollars in exports was left in 2007. [17] Although even at its peak bilateral imports and exports never comprised more than 0.1 percent of Japan’s total trade, this trade had been substantial for North Korea. If actual trade and finance gave Japan any leverage before, this influencing power is now lost due to the measures and sanctions that the Japanese government progressively imposed since 2004. The Japanese government attempted to exert pressure on North Korea through negative sanctions and the prospect of economic assistance that would follow the normalization of relations. It is doubtful, however, that the importance which North Korea attaches to Japanese trade and assistance is as large as this policy assumes, especially when the United States takes a more engaging approach.

In the multilateral context, Japan continuously refuses to cooperate in energy and humanitarian assistance to which the parties committed in February 2007. [18] Even as Pyongyang delivered the belated declaration of its nuclear programme in June 2008 and other parties supplied the remaining shares of assistance, Japan upheld that it would not provide assistance as long as no substantial progress was made on the abductees issue. Moreover, bilateral sanctions on North Korea that were imposed following the missile and nuclear tests in late 2006 remain in place. Only in the run-up to the extension of sanctions in April 2008 did the government show a desire to change to a slightly different course.

The apparent decline in Japan’s leverage is all the more important when put into regional perspective, as it stands in sharp contrast with growing South Korean and Chinese willingness to do business with North Korea. North Korea’s trade with China more than doubled between 2002 and 2006. [19] Although normalization would give the Japanese easier access to North Korea’s raw materials (coal, minerals) and improve their relative economic position towards South Korea and China, the immediate economic gains are obviously much greater for Pyongyang than for Tokyo. Hence, negotiations on normalization and the prospect of stronger economic ties are still a diplomatic card in Tokyo’s relations with Pyongyang.

Not only the state of bilateral economic relations but also the economic and political situation in North Korea itself plays a role in Japan-North Korea relations. [20] Pyongyang feels more confident of leverage over Japan when its economy is in relative good shape. At times of domestic economic crisis and natural disasters (famine, flooding), however, Pyongyang tends to adopt a more welcoming approach towards Tokyo. Indeed, breakthroughs in bilateral consular issues stand in an inverse relationship with the state of the economy of North Korea. Pyongyang does not concede on these issues when its economy is (relatively) stable. Conversely, it adopts a more conciliatory stance when economic crisis is imminent. [21]

Changes in the broader, strategic context inform and reinforce this link between the state of North Korea’s economy and its stance towards Japan. Geo-strategic changes in 1991 prompted North Korea to be more open to communication with Japan. Pyongyang saw the need to engage Tokyo, as its traditional allies Russia and China from the late 1980s increasingly interacted with their old foes. When North Korea’s relationship with the United States was at a low early in the new millennium, Kim Jong-il also saw benefits in improved ties with Tokyo.

Prime Ministers in control: Koizumi, Abe and Fukuda

The prime ministers who ruled Japan since the initiation of the Six-Party Talks in 2003 have taken very distinct policies with regard to North Korea. [22] Unsurprisingly, changes in bilateral policy did not fail to leave their impact in the multilateral setting. Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro revamped bilateral talks in 2000 through the resumption of formal normalization talks, which had been stalled since 1992. He left an important legacy with the first bilateral summits in history, in September 2002 and May 2004. This engaging approach went against the course of President Bush, who early in 2002 famously included North Korea in an ‘Axis of Evil.’ During the first summit Koizumi and North Korean leader Kim Jong-il adopted the Pyongyang Declaration, which formally stated that both sides would ‘make every possible effort’ for an early normalization of relations. [23] The Japanese government moved away from Koizumi’s conciliatory approach, however, when it stalled official talks in 2002 due to its dissatisfaction with Pyongyang’s handling of the abduction issue. [24]

As Chief Cabinet Secretary under Koizumi, Abe Shinzo of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) successfully used the abductees issue, his long-time pet-project, to quickly rise to power. As Koizumi’s successor from September 2006, Abe took a tough stance against North Korea by continuously demanding a solution to the issue. [25] Japan made great domestic and international diplomatic efforts to increase awareness of the abductions and to gain broad support for the abductees as a human rights issue. This proved quite successful in the sense that Washington declared its support, and messages and written statements were adopted at the G8, the United Nations and the Six-Party Talks. Increasingly, however, the Japanese government was also criticized for ‘hijacking’ the Six-Party Talks by overemphasizing the abductee issue. [26]

Formal negotiation on the normalization of bilateral relations restarted reluctantly in early 2006, with settlement of the abductees issue as a Japanese pre-condition for the establishment of diplomatic ties. Although the domestic environment was far from conducive to an improvement in relations, Japan was drawn to the negotiating table because of commitments in the September 2005 six-party agreement. Reopening of negotiations provided an opportunity to confine tension and appeal the abductees issue bilaterally. [27] In certain ways, the Six-Party Talks thus served as a welcome context to talk with North Korea while not seeming weak. [28] However, Abe had mobilized so much public support at home for his policy that there was little room for manoeuvre and policy change had become nearly impossible.

Clearly, the single-issue politics served Abe well. By making normalization conditional to progress in the abductees issue, Japan simultaneously secured greater international interest and maintained a powerful tool to punish North Korea for lack of progress. Some may conclude that narrow domestic political interests simply prevailed over broader strategic purposes. At a deeper level, however, Abe’s policy may be thought of as a conscious attempt to set the bilateral and multilateral political agenda in a context that is framed by a North Korean regime first and foremost interested in negotiating with Washington. Tokyo is generally relegated to the sidelines, expected to provide economic assistance when time is ripe. With little to lose bilaterally and lots to gain domestically and strategically, Abe insisted on this one issue. An obstructing stance furthermore assures that multilateral engagement does not move too fast without real concessions from Pyongyang.

A major flaw in Tokyo’s policy, however, was its failure to anticipate that the United States might change to a more conciliatory approach towards North Korea. [29] A ‘Bush shock’ thus engulfed Japan when the United States in early 2007 receded from its policy of making substantial progress or settlement of the abductees issue a precondition for removing North Korea from its list of state sponsors of terrorism.

By the time of Abe’s resignation in September 2007, the abductee issue had acquired such a high profile that the more conciliatory approach desired by Prime Minister Fukuda needed to be carefully presented. The more accommodating Fukuda strongly hinted that he regarded the nuclear and missile threat from Pyongyang as a more important issue. [30] He had to be extremely careful, however, to avoid the risk of upsetting the Japanese public, which – considering his soft image – would certainly not give him the benefit of the doubt and oppose any policy change without substantial concessions from Pyongyang.

Fukuda aimed for a face-saving way to break the impasse. This approach was in a sense facilitated by the lack of progress in the Six-Party framework in early 2008, which alleviated the need to press on with the abduction issue. [31] Fukuda regarded the Six-Party Talks as a meaningful forum to address larger issues of concern. Also, the multilateral meetings provided a context for bilateral negotiations. A breakthrough seemed apparent in June 2008. Following intense quiet diplomacy on Washington’s side, Pyongyang then agreed to reopen investigation into the abductees and Japan pledged to lift some sanctions. [32] Promises were not followed-up, however, and the stalemate continued.

As the US and North Korea moved towards an agreement in spring 2008 and President Bush announced his intention to remove North Korea from the list of states sponsoring terrorism, Japan was left in an awkward position. Prime Minister Fukuda showed willingness to take a more engaging approach, but needed a positive sign from Pyongyang in order to sell such a policy change to the public. [33] Even as Japan feels the pressure of the more engaging US, policy changes can hardly be justified to the public without progress on the abductees issue. Considering the dire outlook for the North Korean economy in 2008-09 and with Pyongyang likely wanting to seize the opportunity to improve relations with Washington, progress seemed imminent. A breakthrough did indeed come in October 2008 – but it was far from what Japan had hoped for. Forced to choose between moving ahead and upsetting its ally or allowing the deadlock to continue, the Bush administration chose the former. Following almost a week of intense negotiation by the US nuclear envoy and mounting pressure from Pyongyang through the firing of missiles and reported preparation for another nuclear test, Washington removed North Korea from its list of terrorism sponsoring states on 11 October. [34] Japan’s immobilism and North Korea’s decision to await real progress on the side of Japan or the US before proceeding with a reinvestigation of the abductee issue left the Japanese government with empty hands.

Conclusion: Leverage in the Multilateral Effort

Japan’s constrained role in the Six-Party Talks is no surprise. Its policy is two-sided: Tokyo plays a largely circumstantial role in the practical sense and is a powerful spoiler in broader, strategic terms. Its role is circumstantial because its leeway is framed by US initiatives, South Korean consent and Chinese brokering. Japan’s bilateral relationship with North Korea is caught in a multiple relations context and complicated by the fact that Japanese and North Korean willingness to proceed is often at odds. Predictably, Japan’s actual contributions to the multilateral process have thus been minimal. This is true in proposals and suggestions for progress, actions to restart negotiations when talks were deadlocked, and outlining a vision for the SPT process in the context of future relations in and around the Korean Peninsula. [35] Moreover, in refusing to provide energy assistance, Japan’s commitment to the SPT agreements has been half-hearted at best.

The Six-Party Talks negotiating table (entrance behind PRC seat).

From a security perspective, Japan’s concerns over North Korea’s nuclear and missile programmes appear to be at odds with its (in)action in negotiations addressing these issues. When taking a closer look, however, it becomes apparent that while Tokyo recognizes Pyongyang as the greatest threat to Japan’s national security, Pyongyang provides also a welcome justification to the Japanese government for the enhancement of Japan’s security capabilities. The North Korean threat creates leeway to pursue a more proactive military policy and create more offensive capabilities for broader (collective) defense purposes. The abductee issue serves to give the North Korean threat a human face domestically.

Tokyo wants a denuclearized Korean Peninsula and a stable neighbour, but a Six-Party Talks solution – which would enhance China’s standing – is in itself not a priority. Japanese interests are well served by retaining the status quo, which explains why Tokyo has been consciously adopting the role of spoiler.

Three issues are relevant to understanding Japan’s actions. These are Japan’s close relations with the US, its preference for economic rather than political diplomacy, and the dominance of single-issue politics influenced by domestic political considerations. Stable and constructive relations of Japan with the US and neighbouring countries are a general concern. However, the abductees issue shows that Tokyo does not just blindly follow Washington. The Japanese government stuck to its hard-line policy even as the US since early 2007 moved to a more engaging stance. As the US and North Korea made progress in multilateral and bilateral negotiations, the Japanese government started moulding public opinion to allow a softer approach. Nevertheless, real policy changes can only be expected following substantial progress in the abductees issue or in US-North Korea relations. Certainly, the decision by the United States to remove North Korea from the list of terrorism sponsoring states is crucial in this regard.

Economic diplomacy is used by Japanese policy makers in attempts to exercise power in the bilateral and multilateral context. The promise of economic assistance and (humanitarian) aid are substantial ‘carrots’ in negotiations. Furthermore, the prospect of economic assistance that will become available with normalization is thought to give Japan significant leverage. Japanese aid is required for a comprehensive, multilateral solution to the North Korean crisis. Recognizing furthermore that the North Korean nuclear and missile threat justifies the steady build-up of military capabilities, Japan under Abe adopted a hard-line stance towards North Korea. Bilateral sanctions were imposed, trade relations restricted, and financial flows tightened.

Ad hoc single-issue politics is consciously applied by the Japanese government. At times of confrontation, a hard-line posture on (essentially consular) issues makes a powerful distancing impact, while in periods of engagement these issues facilitate improvement in relations. The Japanese government in recent years slowed multilateral negotiations through a focus on the abductees issue and deliberately avoided positive actions in its economic diplomacy to reinforce this policy. Japan assumed that sooner or later it will get what it wants because Japanese money is required for a comprehensive agreement and successful conclusion of negotiations with North Korea in the Six-Party Talks. [36]

Developments since the first half of 2008 show that Japan’s (economic) weight does not impede short-term progress on nuclear issues, however. Fukuda realized that Japan would have little choice but to follow if and when Washington sticks to its engaging approach towards North Korea. This motivated his attempts to soften the government’s hard-line stance in order not to lose face internationally when that would happen. Fukuda’s resignation as Prime Minister on 1 September 2008 and the appointment of Aso Taro as his successor later that month profoundly altered the situation. [37] The announcement on 30 September that Japan would extend sanctions for another six months from October was indicative of a return to the tough stance, that Aso had also taken as a Foreign Minister under Abe.

Aso’s hard-line approach could even have resulted in Japan walking away from the Six-Party Talks after the United States removed North Korea from the list of terrorism sponsoring states. After all, the Japanese Prime Minister had rejected Washington’s compromise plan for verification only days before the announcement. Japan’s withdrawal from the negotiating table is unlikely, however. Aso was quick to downplay Finance Minister Nakagawa’s comment that the American decision to remove North Korea from the terrorism list was ‘extremely regrettable.’ [38] This step by Washington will no doubt revive discussion in Japan about the trustworthiness of the US as an ally, but the fundamental importance of the strategic alignment and the need for Japan to be part of negotiations will take precedence for the foreseeable future. After all, Japan needs to be present at the negotiating table to secure its interests. This includes discussion on the nuclear status of North Korea, another issue on which Washington and Tokyo may be at odds in the future. It should be noted here, that if Aso decides to gradually move towards the softer policy that Fukuda propagated, his hard-line, nationalistic credentials render public resistance less likely than under his predecessor. Japan would then shift away from its obstructionist stance and more actively engage in debates on a (institutionalized) regional security framework, discussion on which has already started. Future developments will largely depend, however, on the outcome of upcoming elections in both Japan and the United States, and the strategic realignments in the US-Japan-China relationship that are slowly unfolding.

Maaike Okano-Heijmans is Research Fellow for Asia Studies with the Clingendael Diplomatic Studies Programme at Institute Clingendael in The Hague and Visiting Fellow at the Asia-Pacific College of Diplomacy of the Australian National University in Canberra.

This is a revised version of a chapter that appeared in The North Korean Nuclear Crisis: Perspectives From Six Powers, edited by Koen de Ceuster and Jan Melissen, Clingendael Diplomacy Paper No. 18, The Hague: Clingendael Institute. Post at Japan Focus on October 21, 2008.

Notes

[1] Kuniko Ashizawa, ‘Tokyo’s Quandary, Beijing’s Moment in the Six-Party Talks: A Regional Multilateral Approach to Resolve the DPRK’s Nuclear Problem’, Pacific Affairs, vol. 19, no. 3, 2006, pp. 411-432.

[2] Many commentators accepted Washington’s claim about the North’s alleged highly enriched uranium programme, while Northeast Asian countries remained unconvinced. Gavan McCormack, ‘North Korea and the Birth Pangs of a New Northeast Asian Order’, Arena, Special Issue No. 29/30, 2008.

[3] Looking back on this period Shigemura harshly criticizes the Japanese government for being weak and having been too eager to enter the SPT, arguing that the success of a Six-Party agreement depends on willingness of the Japanese to provide funds. Shigemura Toshimitsu, Chosen Hanto ‘Kaku’ Gaiko – Kitachosen no Senjutsu to Keizairyoku [Korean Peninsula ‘Nuclear’ Diplomacy’ – North Korea’s Strategy and Economic Power] (Tokyo: Kodansha, 2006), pp. 63-64.

[4] Various issues of the annual Diplomatic Bluebook, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Defense of Japan, Ministry of Defense (before 2007, Defense Agency).

[5] The Japanese government currently identifies seventeen Japanese citizens as having been abducted by North Korea and continues investigations into other cases in which abduction is not ruled out. Five abductees returned to Japan in 2004. North Korea long asserted that eight abductees died and that it has no knowledge of the four others. In June 2008, however, Pyongyang agreed to reopen investigation into the issue. For the Japanese viewpoint, see: