The Ryukyus and Taiwan in the East Asian Seas: A Longue Durée Perspective

By Man-houng Lin

Traveling through East Asia, one can view historic imperial palaces in Beijing and Tokyo, and royal palaces reconstructed from the ruins left by fire and war in Seoul and Naha. Okinawa is the largest island in the Ryukyu archipelago. The Shuri palace in its capital, Naha, was constructed more than six hundred years ago by the rulers of the Ryukyu kingdom, which played a crucial role in maritime East Asia from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. Today, it takes barely an hour to fly from Taipei to Naha, and the Shuri castle, reconstructed three times in the last century, has been designated a World Heritage Site in an attempt to evoke its former grandeur.

The Ryukyu archipelago is composed primarily of coral reefs. The restored palace in Naha raises the question of how a large-scale political system emerged on these islands; on Taiwan, which is far larger and richer in natural resources, a political and economic order of comparable sophistication did not appear until later. Is there a connection between the decline of the Ryukyu kingdom and the rise of Taiwan? What can be learned from the Ryukyus’ transformation from a kingdom and a Chinese tributary state to a Japanese prefecture—and from Taiwan’s incorporation by China, then by Japan, and then by China again, as well as its subsequent rise as an economic force? In both the Ryukyus and Taiwan, the characteristics of kingdom and nationhood have been heavily conditioned by the location of these insular territories in relation to China and Japan. Drawing on the author’s research on related issues [1], this article will address these questions by examining the longue durée in East Asian maritime history, spanning the fourteenth to the twenty-first centuries.

The Ryukyu Kingdom as “Bridge to the Various Kingdoms”

The key to the rise and fall of the Ryukyu kingdom was its crucial role as an intermediary in maritime East Asia. During China’s Tang dynasty (618–906 CE), the Ryukyus paid tribute to Japan, but tributary relations with Japan were subsequently broken off. Thereafter, from the Song dynasty through the Ming dynasty (976–1644), the Ryukyus maintained commercial relations with Japan, Korea, and China, as well as with Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands. During the Yuan-Ming transition of the fourteenth century, as Japan entered a period of conflict between northern and southern dynasties (1336–1392), the so-called wako pirates emerged from Kyushu and became active in the coastal regions of China. Not long after the Ming succeeded the Yuan, these pirates united with anti-Ming forces and threatened the new regime. In order to control the resulting unrest, the Ming founder Zhu Yuanzhang not only forbade maritime trade but also established a tribute system, in an attempt to transform the smuggling trade (conducted by the pirates and anti-Ming forces) into a trade nexus controlled by the Ming government. The Ming invited Japan to take part in the tribute trade on condition that it pacify the pirates, but this invitation was refused. Since the pirates frequently moored in the Ryukyu archipelago en route to China, the Ming offered the Ryukyu kingdom favorable conditions for engaging in the tribute trade as a means to eliminate the pirates. Tribute trade was established with the Ryukyus beginning in 1372, as political forces within the Ryukyus gradually moved towards unification.

Within the Ming tribute system, the position of the Ryukyu kingdom as a tributary state of the Chinese empire was more important than that of others, and the Ming allowed the Ryukyu kingdom to engage in lucrative tribute missions more frequently than any other state. Today, in Naha, there is a replica of an ancient bronze bell that was cast in about 1458. Roughly as tall as a person, it is as wide as four people. On the outside is inscribed an essay, “The Bridge to the Various Kingdoms,” which frankly states that the Ryukyu kingdom was the intermediary for trade among Japan, Korea, Southeast Asia, and China. Such a claim was plausible given the fact that the Ryukyu kingdom was the most frequent tribute bearer to China, that bilateral trade accompanying tribute missions was extensive, and that many other nations transited the Ryukyus en route to China. As a result, the Ryukyus developed strong trade relations with numerous other countries. This role as “bridge to various kingdoms,” pivoting on the Ryukyu-China tributary relationship, enabled the Ryukyus to flourish.

Replica of the Bankoku Shinryo

(“bridge to various kingdoms”) bell

Taiwan Gradually Eclipses the Ryukyus

From around 1540 to 1700, trade in Japanese silver and Chinese silk was the most important economic activity in maritime East Asia. In this period, under the “single whip” fiscal reform, taxes formerly paid in kind, in corvée labor, or in copper cash, were consolidated and paid in silver. The use of silver among the people was also greatly expanded. About three quarters of China’s silver at this time came from Japan, with western Honshu (near Kyushu) as the mining center. The expanding trade in Japanese silver and Chinese silk was not direct trade; in this respect it closely resembled the growing commercial ties that have developed between Taiwan and mainland China since the 1980s. Even now, Taiwan does not allow direct trade with China, so the trade relies upon transit via Hong Kong, Cheju Island (off the southern coast of Korea), and other ports. Similarly, before the eighteenth century, Korea, Hanoi, Macao, the Ryukyus, and Taiwan were all transshipment points for the Sino-Japanese silver-silk trade. At that time, Taiwan displayed no traces of nationhood in the modern sense. The island was not, however, isolated. Many Fujianese traders such as Koxinga’s father came to the island, and the Dutch and Koxinga subsequently established trading outposts for the transit trade in Chinese silk and Japanese silver.

Besides silk, Japan also exchanged silver for China’s more advanced technology; as a result, Japan’s domestic economy expanded while its silver production decreased. From about 1700 the Sino-Japanese silver-silk trade began to dry up, and it appears that it completely vanished by around 1775. For its part, with the rise to prominence of numerous transshipment ports in maritime East Asia, the Ryukyu kingdom lost its monopoly status as “the bridge to the various kingdoms.” Moreover, during the eighteenth century the Satsuma (present-day Kagoshima) daimyo from Kyushu gradually asserted control over the Ryukyus and imposed a new tributary order, featuring a growing number of tribute missions from Naha to the Edo bakufu. Far from forcing the Ryukyu kingdom to terminate its tribute missions to China, Satsuma encouraged expansion of the missions and utilized them to conduct subterranean and lucrative Japan-China trade.

Although the Ryukyus sought to incorporate more Chinese cultural elements as a means of asserting autonomy from, and superiority to, Japan, strict control through Satsuma increased steadily. In 1872, the Japanese government established the Ryukyu han, placing the Ryukyus under the jurisdiction of the Foreign Ministry. Subsequently, in 1874, after the Botan tribe incident in Taiwan, Japan ordered the Ryukyus to terminate tribute relations with China. The following year, Japan transferred jurisdiction over the Ryukyus from the Foreign Ministry to the Home Ministry, and in 1879 it formally brought the Ryukyus under Japanese sovereignty, establishing it as Okinawa Prefecture and forcing the Ryukyu king to move to Tokyo. Although China had long opposed Japan’s control of the Ryukyus, it signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki after its 1895 defeat in the China-Japan War, thereby ceding Taiwan to Japan and abandoning its claims to the Ryukyus.

While the Ryukyu kingdom’s role as an intermediary thus diminished, trade in Japanese silver and Chinese silk would continue to drive Chinese maritime economic activities. By contrast, Taiwan would expand its role as an intermediary in East Asian maritime trade, including trade with China.

Trading Centers of East Asia, Old and New

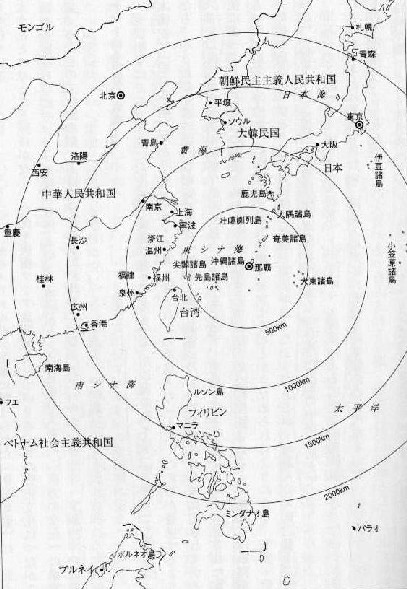

Recent histories of the Ryukyus usually include a map with Ryukyu at the center of East Asia, which was created by Ryukyu scholars after 1945, but which roughly illustrates the international trade status of the Ryukyus during the period when it was “the bridge to various kingdoms.” (scroll down)

Map 2: The Ryukyus at the center of maritime East Asia

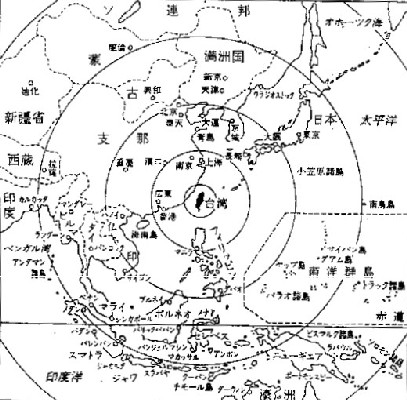

In 1944, the Asahi Shimbun published a map that showed Taiwan at the center of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Map 3: Taiwan as the center of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

The two maps closely resemble one another. However, the periods in which the Ryukyus and Taiwan gained central positions in regional trade differed by about five hundred years. Taiwan did begin to emerge as a trading center as early as the expansion of the Japan-China silver-silk trade of the seventeenth century; in addition to supporting trade in silver and silk, Taiwan served as a transit site for trade between China and Southeast Asia, and even Europe. This changed, however, after Taiwan became part of the Qing in the eighteenth century, leading to its disappearance from international trade routes even as Taiwan-China trade continued to grow. During the decades prior to Japan’s 1895 occupation of the island, Taiwan’s trade partners expanded to include the United States, England, Germany, Japan, and other countries; nevertheless, its status as a transshipment port in international trade remained weak. Indeed, its trade with Europe, the United States, and Japan had to be transshipped via Hong Kong, Xiamen, and other Chinese coastal harbors.

When Japan occupied Taiwan in 1895, it sought to imbue the island with the same status that Hong Kong enjoyed as the main transshipment port for the British Empire. Taiwan’s role in the transit trade expanded rapidly as a result. As Japan replaced China as Taiwan’s primary trading partner, significant quantities of Japanese goods began to pass through Taiwan en route to both China and Southeast Asia. Taiwan’s tea and camphor, which had previously gone through the Atlantic for sale in Europe and then the United States, now crossed the Pacific Ocean for sale to the US.

In the 1910s, Hong Kong became the largest port in East Asia, and by the 1930s its trade volume was the seventh largest in the world. Kobe and Osaka vaulted respectively into the positions of third and fifth largest, with New York first, London second, and Rotterdam fourth. Taiwan shared in this rise to prominence of the Asia-Pacific as a world maritime region. When Japan launched the East Asian War in 1941, Taiwan’s position at the center of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere grew in importance. After Japan was defeated in 1945, Taiwan came under the control of the Republic of China, and for the next four years, China replaced Japan as its primary trade partner.

After the Republic of China moved to Taiwan in 1949, and particularly after the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, Taiwan became a US stronghold on the front lines in the Cold War in Asia, and the US sought to strengthen Taiwan’s economic integration with Japan and Southeast Asia while cutting ties with the mainland. In 1952 the Republic of China and Japan signed a Peace Treaty at the Taipei Guest House (the former residence of Japan’s colonial Governor-General in Taiwan), in which Japan formally renounced sovereignty over Taiwan and the Pescadores, which it had obtained in the Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895. Following the treaty, Taiwan quickly regained the importance it had enjoyed as a trade center at the heart of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere by strengthening ties with the United States and Japan and linking with Southeast Asia, even while denied access to mainland China. The Republic of China on Taiwan became a major trading nation, with the US and Japan as its leading partners.

As for the Ryukyus, in 1945, after a battle that took the lives of more than one quarter of the population and devastated the main island, the US seized the Ryukyus as a military colony and the center of its ring of bases in East Asia. The 1951 San Francisco Treaty ending the US occupation of Japan left Okinawa’s colonial status intact, but it affirmed that Japan held residual sovereignty over the Ryukyus. Japan extended preferential treatment to the Ryukyus through low tariffs and other privileges in a bid to woo Ryukyuan support for eventual reincorporation into the domain of its former colonizer. In 1972, the US restored Japanese administrative authority over the Ryukyus while retaining its vast network of military bases, and the islands were again renamed Okinawa Prefecture.

Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato

(left) negotiated with Richard Nixon

for the return of Okinawa to Japan

Taiwan’s Future

In the final decades of the twentieth century, trade patterns in East Asia were transformed. According to the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), Japan’s imports from nine East Asian nations (led by China, South Korea, and Taiwan) have outstripped the combined total of its imports from the US and Europe in every single year since 2001; the same has been true of its exports since 2002. [2] While the US has remained Japan’s single leading export market, the growing dominance of East Asia among the trade partners of Japan and other East Asian nations is the dominant pattern emerging throughout the region. It is tempting to note similarities to the intra-Asian trade during the silk-silver period of 1540–1700.

South Korea is among the nations that benefit from rapidly growing trade and investment with China today. At the same time, it re-emphasizes the fact that the name of its capital city was Seoul rather than Hancheng, which literally means a “Chinese castle.” And while Japan’s exports to South Korea advanced at solid double-digit rates in the years 2001 through 2004 (before slowing in 2005), Korea has not hesitated to criticize Japan sharply over the Dokdo/Takeshima island conflict and historical memory issues, including textbooks and reparations for Korean forced laborers. By contrast, many Taiwanese, long indoctrinated with the view that Taiwan was part of “China,” are not clearly aware that the “China” of which it has been part is the Republic of China (ROC) consisting of Taiwan, the Pescadores, Quemoy, and Mazu, the territories specified in the 1952 treaty signed by Chiang Kai-shek in Taipei. In 1993, when the ROC had its last quasi-official encounter with People’s Republic of China (PRC) representatives at Singapore, both sides cited the Cairo Declaration as basis for their claim to Taiwan; the only difference is that the PRC reduced “the Republic of China” in this Declaration to “China,” while the ROC underlined “the Republic of China” exactly as written in the Declaration. The 1952 treaty was not mentioned by the KMT regime at this point. Since the DPP came to power in 2000, they have deemed “the Republic of China” a designation used by the KMT and have not accepted the 1952 treaty as a basis for Taiwan’s legal status.

Since June 4, 2006, the Taipei Guest House has been opened to the public once every two months following a US$13 million renovation. There has been no mention of the fact that this is the site where the 1952 treaty was signed. In four of five high school history textbooks issued in September 2006, the DPP government does not mention the 1952 treaty; the sole exception states that the treaty has not settled Taiwan’s legal status but that Taiwan has de facto sovereignty. In short, the DDP continues to teach the coming generation that Taiwan’s status is not settled. Without using the longue durée interaction between China and Japan to determine Taiwan’s historical alignment, as presented in this essay, the significance of the 1952 treaty for defining Taiwan’s legal status cannot be fully comprehended.

As indicated in the 1952 treaty, the Republic of China today, like the historical Ryukyu kingdom, is a small nation between great powers in East Asia. The Ryukyu kingdom imported Confucianism, the Chinese classical language, and Chinese folk religion from China, and it imported Buddhism from Japan. In the Ryukyu kingdom, Chinese officials held positions of influence and power, while Japanese monks were deemed national mentors. As China-Japan rivalry intensified in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Chinese calendar was used when Chinese envoys came, and the Japanese calendar was applied when Japanese envoys visited. Ryukyuans conducted tributary missions to both the Chinese and Japanese capitals.

Adroit diplomatic and cultural strategy as bases for sustaining the economy, and achieving a sense of dignity, are lessons of the Ryukyu kingdom legacy for Taiwan.

By Man-houng Lin, Research Fellow, Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica. This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in the Academia Sinica Weekly, No. 1084 (2006.8.24). It was translated with the assistance of Evan Dawley. Lin’s most recent book is China Upside Down: Currency, Society, and Ideologies, 1808–1856.

Posted at Japan Focus on October 27, 2006.

Notes

[1] China Upside Down: Currency, Society, and Ideologies, 1808-1856, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006, Chapter 1; Historical contemplations on relations between Taiwan and Chinese Mainland (in Chinese). Taipei: Maitian Press, 2002; “Elite Survival in Regime Transition: Government-Merchant Cooperation in Taiwan’s Trade with Japan, 1950-1961,” in The International Order of Asia in the 1930s and 1950s, edited by Shigeru Akita and Nick White (London and New York: Ashgate, 2006); Review of Akamine Mamoru, “Ryukyu Kingdom” (in Chinese), Modern History Bulletin, Academia Sinica, Taipei, September 2006.

[2] See www.jetro.go.jp/jpn/stats/data/pdf/trade2005.pdf.