Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a “Japanese-style Immigration Nation”

Lawrence Repeta with an introduction by Glenda S. Roberts

Introduction

Since the Democratic Party took power in Japan with the Hatoyama administration in September 2009, there has been little movement on immigration issues in Japanese politics. There has, however, been notable discussion by civil society commentators who are advocating the establishment of some form of regularized immigration policy as a partial solution to Japan’s demographic decline. Among them one could mention the policy proposals made by the Council on Population Education/Akashi Research Group (2010), “Seven Proposals for Japan to Reestablish its Place As a Respected Member of the International Community: Taking a Global Perspective on Japan’s Future.” One of the seven proposals is to enact an Immigration Law and establish an Immigration Agency. The Council notes, “Political will and leadership will be required to take the necessary action for the enactment of such a law” (Council on Population Education/Akashi Research Group, 2010:6). In the current economic doldrums, however, with the media reporting on the difficulties even college students are facing trying to secure jobs before spring graduation, this political will is quite unlikely to surface.

These ideas of creating a country open to immigration began to appear some years ago as Japanese grew alarmed at projections showing the nation’s aging and shrinking population. Among the more recent manifestations was the Project Team of 23 members of the Liberal Democratic Party, inside its Division of National Strategy, which issued a policy proposal in 2008 entitled “Opening the Country to Human Resources! The Road to a Japanese-style Immigration State: Towards Building a Country where the World’s Youth Yearn to Immigrate.” (Nihongata Imin Kokka he no Michi Purojekuto Chiimu, Jiyū Minshutō Kokkasenryakuhonbu Project Team for a Japanese-style Immigration Nation, LDP national strategy division), 12 June 2008.) This report did not by any means have unanimous backing of the LDP at the time, but it is interesting that it was published.

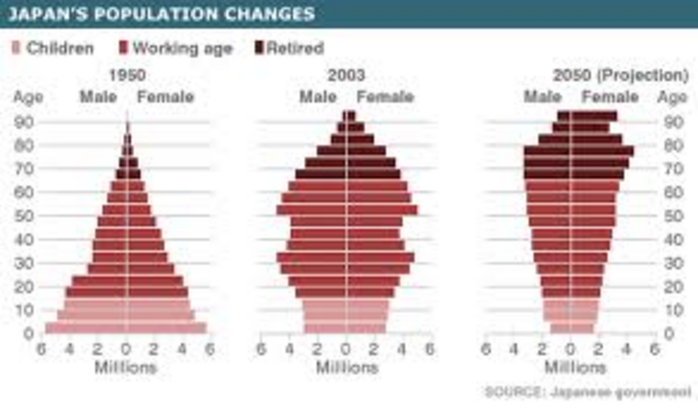

|

Projections of Japan’s population profile, 1950-2050 |

Lawrence Repeta’s report presents the proposal of another highly vocal proponent of immigration, Sakanaka Hidenori, the founder of the Japan Immigration Policy Institute. Mr. Sakanaka has also formed a study group on the immigration society, which has met in Tokyo three times since the summer of 2010 and is ongoing. He continues to be very vocal and active in promoting the notion of opening up Japan to immigration.

Mr. Sakanaka’s proposals to create an immigration nation are, as indicated below, in a broad brush-stroke stage. He has a great deal of enthusiasm for this program, but as yet, while he may not be singing solo, his voice has not carried far. To me, a main area that would strongly need to be addressed were Japan to follow this path toward a multi-ethnic society would be, in K-12 education, to develop an appreciation of and understanding for people from many different ethnic backgrounds, so as to be able to welcome them as equals at the national table.

|

Immigrant children in a suburban Tokyo school celebrate Peru’s independent day |

When my son was an elementary student in a Japanese urban public school, he came home one day all excited, telling me he knew what he would want to be when he grew up: a rice farmer in Japan, so that he could save Japanese agriculture from all the nasty American pressures. It’s interesting that my son may not have been so far from reality — Mr. Sakanaka is actually proposing, among other things, that foreigners could be saviors for Japanese agriculture. At the same time, however, in 2009 I had occasion to have a long conversation with a part-time weekend rice farmer in Aichi prefecture. This man, self-identified as one of the “working poor,” was renting a small plot from a local landlord and working for an agricultural NPO during the week. An economics major of a private university in Tokyo, he could not find a job when he graduated shortly after the Bubble burst in 1991, and he turned to the countryside for escape and solace. He had hoped to settle there, but he said wryly and with some bitterness, he would have to return to the city in retirement, because nobody in rural Aichi welcomes men like him for long-term settlement; they were too closed to outsiders. He was not married and had no prospects among the locals. When I reflect on this man’s narrative, I cannot help but wonder how local people in the countryside would deal with long-term foreign immigrants. From trainee farm and fishery hands and factory workers to brides in international marriages, the Japanese countryside is already getting a lot of help from thousands of foreign migrants, but it is still a question as to how foreign populations will be accepted for the long term.

Actually there has already been substantial long-term newcomer immigration to Japan, in the form of student migrants from China who have stayed on to become permanent residents and Japanese nationals, engaged in many varieties of professions and businesses, both in Japan and transnationally. But this positive example of migration and settlement has attracted little note in the public eye (see Helene LeBail, forthcoming and Gracia Liu-Farrer, forthcoming). This new immigration project, if it is to succeed, would have to be a really life-altering long engagement for all parties concerned. If the immigration nation does come to pass as a “front door” initiative, Japan may well learn from her neighbor Korea across the straits, who as Keiko Yamanaka (forthcoming) illustrates, has already embarked upon opening the nation to newcomers. But without further ado, I leave the readers to ponder the outlines of the ‘Immigration Nation’.

Glenda S. Roberts

References

Council on Population Education, Akashi Research Group, 2010: link (accessed on 298 November 2010).

Le Bail, Helene. “Integration of Chinese Students into Japan’s Society and Labour Market,” in Gabriele Vogt and Glenda S. Roberts, eds., Migration and Integration, Japan in Comparative Perspective. Forthcoming in 2011, Iudicium.

Liu-Farrer, Gracia. Labor Migration from China to Japan: International Students, Transnational Migrants. London and New York: Routledge, Forthcoming.

Nihongata Imin Kokka he no Michi Purojekuto Chiimu, Jiyū Minshutō Kokkasenryakuhonbu (Project Team for a Japanese-style Immigration Nation, LDP national strategy division), 12 June 2008. Available here.

Keiko Yamanaka, “Policy, Civil Society and Social Movements for Immigrant Rights in Japan and South Korea: Convergence and Divergence“ in Gabriele Vogt and Glenda S. Roberts, eds., Migration and Integration, Japan in Comparative Perspective. Forthcoming in 2011, Iudicium.

The international news media has recently drawn attention to some disturbing aspects of Japan’s immigration – or, perhaps non-immigration – policy. In coverage immediately prior to the July 11 House of Councillors election, a Reuters report stressed that Japan’s politicians would do anything to avoid discussing immigration, a topic “too hot to touch.” (Link) Two weeks later, the New York Times reported on the plight of foreign workers brought to Japan under job training programs who are often paid substandard wages, suffer through hellish work-days and nights and may even become victims of karoshi – death by overwork. Link.

Human rights activists have long decried this state of affairs and in 2008 succeeded in persuading the UN Human Rights Committee to issue a formal recommendation that these programs be eliminated and replaced with “a new scheme that adequately protects the rights of trainees and interns and focuses on capacity building rather than recruiting low-paid labour.” (See Item 24 of the Concluding Observations of the Human Rights Committee, December 18, 2008, here.1)

Like their counterparts around the world, Japan’s politicians focus on the short-term issues of greatest significance to the next election while avoiding the hard questions that may have the greatest impact on the longer-term interests of society. In Japan’s case, the big issue that dwarfs all the others is the looming demographic crisis. Population growth turned negative in 2005 and all projections suggest a decline in Japan’s population of at least 25 million by the middle of the 21st Century. Moreover, the combination of sharp decline in Japan’s total fertility rate together with the world’s longest average lifespan means that the population is rapidly aging. Pondering the thought that by mid-century the number of Japan’s octogenarians will exceed the number of its children, Professor Vaclav Smil has written “the expected continuation of Japan’s population decline and aging will take the country into an unprecedented, and truly extreme, demographic territory, making it an involuntary global pioneer of a new society.” (Smil’s chilling overview of these issues, “The Unprecedented Shift in Japan’s Population: Numbers, Age, and Prospects” is available here)

The obvious strategies for arresting such a decline are to increase the birth rate and to increase the number of immigrants. Since taking power last year, the Democratic Party of Japan has proposed and taken various measures to achieve the former, but has said little about the latter.

Sakanaka Hidenori, an immigration official who served in the career Ministry of Justice for 35 years before retiring in 2005, has become well-known as an outspoken advocate for increased immigration. In 2005 he founded an NGO devoted to immigration issues. (See this link.) In a booklet published in 2007 and translated into English last year, he calls for an inflow of 10 million new immigrants by 2050. In his words, “immigrants can save Japan,” but in order to attract them, Japan must become a multiethnic society and “a country that gives dreams to foreigners.” (The entire English text (including the very helpful introduction by translator Kalu Obuka has been made available online by Debito Arudo here.) The importance of Sakanaka’s work lies not only in his long experience in government, but also in the fact that this is perhaps the most ambitious immigration program framed by any Japanese intellectual or public figure to date. Moreover, his target of 10 million new immigrants by 2050 has entered public discourse as a subject of debate.

|

Sakanaka Hidenori |

If Japan were to pursue Sakanaka’s goal, many questions follow. Where would the 10 million newcomers live? What jobs would they perform? What educational opportunities would be available for their children? What medical, pension and other social services would be made available? Would the Japanese people support such a policy? What would they think of their new neighbors? Would these people be happy in Japan? Sakanaka himself calls for creation of a “multiethnic Japan.” His booklet is a bit short on hard data or qualitative research, but it does present a series of proposals that taken together comprise a rough agenda and his major statement on the issues. The purpose of the following text is to summarize the specific elements of the Sakanaka Agenda, providing relevant quotes from the original text.

Japan as “Immigration Nation” — The Eight Key Elements of the Sakanaka Agenda

Sakanaka’s “Immigration Nation” proposes at least eight discrete policies or goals directed at creating the infrastructure to welcome 10 million new immigrants and transform Japan to become a multiethnic society.

1. Shift from Temporary Workers to Immigrants

2. Education as a Magnet

3. Reforms to Education and Employment

4. Corporate Social Responsibility

5. Revitalizing Agriculture

6. Multiethnic Japan

7. Ministry of Immigration

8. “Immigration Social Workers”

Each of these elements is summarized below with quotations of key passages from “Immigration Nation.”

1. Shift from Temporary Workers to Immigrants

Sakanaka places his greatest hope on the shoulders of foreign graduates of Japanese universities. This highly educated cohort would form the nucleus of the ten million. “In addition to taking up measures for receiving 300,000 foreign students, I believe my favoured plan for one million foreign students should be adopted. It would be the central pillar of my plan for ten million immigrants. The institutions of higher education where students of diverse nationalities and ethnic backgrounds would learn will be “treasuries of talent,” and a source for future immigrants. Should the plan for one million foreign students progress steadily, with 70% of them finding employment in Japan, and a system for facilitating permanent residence established, the plan for accepting ten million immigrants set forth in the Japanese-style immigration policy will easily become a reality.”

Sakanaka’s focus is on permanent residents who may be candidates for Japanese citizenship. He writes that he is “against bringing in temporary foreign workers, including trainees in technical skills. Temporary foreign workers were brought in to compensate for shortages in the manufacturing industry as low paid migrant workers to be sent back home once there was no longer any need for them.” He acknowledges that government policy has led to major disappointments, especially regarding Brazilians and other Latin Americans of Japanese ancestry. (See the “Corporate Social Responsibility” section below.) He stresses that temporary worker programs are a poor fit for Japan’s needs. “Countries undergoing population decline don’t need temporary foreign workers, they need people who will settle long-term, i.e. immigrants. We need to give immigrants incentives to live and work permanently in Japan and integrate them into our regional communities.”

What kind of immigrants would be accepted under the Sakanaka plan? He envisions five categories: “graduates of Japanese institutions of higher education, students receiving vocational training in specialist schools, the families of immigrants, humanitarian immigrants (asylum seekers and refugees), and those who’ve come to make investments (i.e. the very wealthy).”

2. Education as a Magnet

At the heart of Sakanaka’s proposal lies “the utilisation of Japanese higher education and vocational training institutions to equip foreign nationals with skills, support with employment, and recognition of long-term settlement.” Capacity is available. “Due to the decline in the number of young people, educational institutions such as universities and agricultural high schools have plenty of excess capacity.”

Regarding the availability of vocational training he writes “Due to population decline we have plenty of room in high schools specialising in agriculture, manufacturing, and fisheries, and in vocational training institutions. Three-year training curricula will be established that will, beginning with Japanese language instruction, teach trainees specialist skills. There will be another year of on-the-job training for those who complete their course of study.”

Individuals who complete this curriculum would incur an obligation. “The framework of my plan to encourage work and settlement would have two conditions. 1) That trainees complete the course and seek work in Japan, and 2) that they are employed as regular full-time employees by businesses that practice vocational training.”

“We would nurture talent through the Japanese education system, provide vocational support for those who want it, and then encourage them to settle in Japan. At the same time, those who decide to return to their home countries are also important; as they will put the skills and knowledge they gained in Japan to use contributing to their country’s economic development.” Throughout the book, Sakanaka repeatedly emphasizes that Japan should avoid creating a “brain drain” from developing countries. Here he seems to propose that Japan’s educational system be offered as a resource for the world. He does not mention the American or other systems as models to be emulated, but the parallel with the existing population of inbound students seeking opportunity through universities in the United States and elsewhere is obvious.2

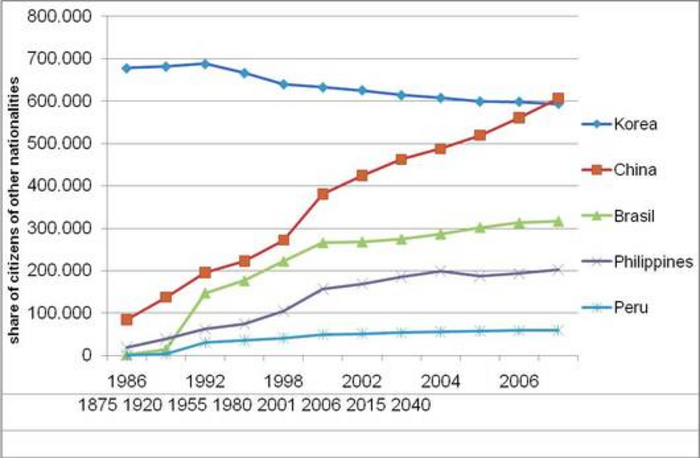

Immigrants to Japan 1986-2006 by nationality

3. Reforms in Education and Employment

Sakanaka does admit there are issues to be addressed. He recognizes that Japan faces competition in its efforts to attract talented students. Success for his model “depends on whether or not we can draw young people from around the world to our higher education institutions and nurture high quality graduates.” These people must decide that Japan is a preferred alternative in their pursuit of paths toward successful careers.

He also expresses the concern that Japan’s educational system and managerial practices may not be quite ready for the burden he would place on them. “Providing a suitable environment for research and education for foreign nationals is a pressing issue. We should reform the university system in order to raise the level of education for foreign students. Moreover a substantial scholarship system and the construction of student lodging are imperative. Japanese universities are struggling financially due to population decline and the shrinking tuition it entails. In an effort to raise funds they fill their places by recruiting foreign and domestic students, with less priority given to academic standards. If these practices continue our most talented Japanese students will go to higher quality universities overseas, thus the deterioration of the Japanese higher education system would continue.”

“There also needs to be a reform of the awareness of companies that employ foreign students, and the establishment of a culture of management that gives status and salary based on ability, regardless of ethnicity or nationality. There should be a multiethnic setting that draws out the artistic talent and creative expression of foreign students who have a global view, and puts them to practical use. If foreign students do not feel drawn to Japanese companies we will lose their talents to other countries. Foreign students have a strong desire to improve their social standing, and want to be evaluated in a just manner by Japanese companies. If the level of discrimination against foreign nationals in Japanese companies does not change, even after making the effort to bring in 300,000 students we cannot expect to significantly raise the number of foreign nationals who will seek employment.”

4. Corporate Social Responsibility

Sakanaka recognizes that corporate employers must play a central role if his plan is to have any chance of success. To gain their cooperation, he would insist that principles of “corporate social responsibility” be applied to the employment of the immigrants. He describes the case of Japan’s Brazilian workers as a fine example of how not to go about it.

“Of the over 300,000 Brazilians in Japan, many of them live in the Tōkai region between Toyota city in Aichi Prefecture and Hamamatsu city in Shizuoka Prefecture. Famous Japanese automakers such as Toyota, Honda, Suzuki and Yamaha are concentrated throughout the Tōkai region. In order to maintain price competitiveness they’ve been systematically employing cheap labour.

“Most Brazilians who work for subcontractors and sub-subcontractors are employed as factory workers with fixed term contracts, or are employed indirectly through dispatch companies, which place them in assembly lines. The current global recession has placed us in a position to seriously question what kind of social responsibility corporations have to these kinds of irregular workers.” Of course, “fixed term” means that employers are free to eliminate their workers when the term expires.

At this point, Sakanaka makes a useful connection to a relevant international standard. “At the international level the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is grappling with issues of corporate social responsibility. If we look at the proposed standard concerning foreign nationals they are looking to have come into effect in 2010, it lists immigrants, foreign workers, and their families as a category of socially vulnerable people to whom particular attention must be paid. It goes on to say organisations must respect their rights, and make every endeavour to create an environment where these rights are respected. These rights are the freedom from discriminatory labour practices – including hiring, selection, access to training, promotion and dismissal – on the basis of race, skin colour, sex, age, ethnicity, nationality, and society or country of origin.” See this link.

“Car manufacturers appeared to ignore this trend towards increased attention to the rights of foreign workers, for when the effects of the world recession were felt in Japan the first to be laid off were large numbers of Brazilians of Japanese descent. These companies claimed that they were simply not renewing contracts with dispatch workers and subcontractors once the end of their contract period had been reached. However in actuality they were simply using the weak position of irregular workers to their advantage.”

5. Revitalizing Agriculture

Sakanaka identifies “the revitalisation of Japanese agriculture” as a national policy objective and makes it the subject of much discussion. He states that “the root cause of the weakening of our agricultural industry is the drop in the number of workers.” His solution is obvious: “in order to rescue Japanese agriculture from this hopeless state of affairs I propose bringing in 50,000 agricultural immigrants, and recovering about 400,000 hectares of abandoned farmland as a special “immigrant agricultural zone”. Firstly upon request from local government bodies, focusing on the abandoned farmland in each administrative division, the cabinet will designate a fixed area as a ‘special immigrant agricultural zone.’ At the same time, agricultural production firms (hereafter I will refer to them as ‘Special Producers in Agriculture’ [SPAs]) in these zones that will employ agricultural immigrants will be designated.

In this way the core investments, and management will be designated as the responsibility of the Special Producers in Agriculture. We will put forth financial and tax-based incentives in order to concentrate SPAs in the small-scale rural farms, mountain forest areas, and arable lands poorly managed by absentee landlords.”

Again, the author identifies excess capacity in Japan’s schools as a valuable asset. “We will recruit young people from around the world who wish to pursue careers in this field into agricultural ministry-affiliated institutions for higher education, and agricultural high schools. These educational institutions (two year system, 43 throughout the country, with a combined total capacity of about 4000 places) and agricultural high schools (three year system, 400 schools, 8000 places) are already in place, however the number of prospective students continues to fall. So that these specialist institutions do not go to waste, my plan is to use them to educate the foreign nationals we will bring in to work in the agricultural industry….”

“In order to provide the necessary funds for the education of agricultural immigrants the government and the SPAs will create a special fund. The Special Producers in Agriculture will employ graduates of these agricultural schools as regular full-time workers with the same duties and salaries as Japanese. After their employment is confirmed, their status will be changed from student to permanent resident.

“SPAs will run an intensive, flexible agricultural industry by renting fallow land, abandoned farmland, and mountain forest areas with absentee landlords. Furthermore, multi-faceted management, including that of food and timber industries, and animal husbandry will be developed. SPAs will manage both agriculture and forestry, making sure that there is work for agricultural immigrants throughout the year. Agricultural immigrants will, as a rule work from spring to autumn in agriculture, and forestry in winter. Immigrants will live in the towns, where they will have access to schools, hospitals and other basic amenities, and commute to their places of work in more remote areas. In the cities where these agricultural immigrants are concentrated, we will build industrial zones for secondary industries such as bio-fuel, food processing, meatpacking, dairy, and timber processing plants.

Sakanaka’s ambitions for Japanese agriculture do not stop with the home market. “As well as tackling the improvement of the Japanese brand through agricultural skills, I want Japan to become a leading exporter of high quality nutritious rice, fruit, and meats.”

6. Multiethnic Japan

In order for his plan to succeed, Sakanaka says there must be a “social revolution,” featuring a fundamental shift of the national self-image from that of a homogeneous society to one that is multiethnic.

“The very fundamentals of our way of life, the ethnic composition of our country, and our socio-economic system will have to be reconsidered and a new country constructed. In terms of policies towards foreign nationals; if we are to solve our demographic malaise by becoming an immigrant country we must transform Japan into a ‘country that gives dreams to foreigners’; a place where young people from around the world would aspire to migrate to. We must make ‘a fair society, open to the world’ that guarantees everyone a fair chance, regardless of ethnicity or nationality, and judges people by their achievements. It is an essential requirement that this society comes to value diversity more than uniformity.”

He declares that Japan must abandon its exclusionary social practices and even that “Japanese people must also abandon their privileges.” What privileges does he have in mind? For example, “in order to bring immigrants into agricultural fields, corporations and other business would have to form agricultural companies (PLCs), lease land from farmers, hire foreign graduates of agricultural specialist schools as regular full time workers, and develop large scale food production; Requiring the implementation of a whole new structure of agricultural management, which is likely to be painful, as the new system would fly in the face of many vested interests. Even so, the immigration policy I’m proposing will provide skilled people, and as a result enlarge our agricultural workforce, and raise our degree of self-sufficiency in food.”

7. Ministry of Immigration

At the same time he would persuade Japanese people to abandon their privileges, he would “encourage immigrants to adapt to Japanese society.” To achieve this, he would “provide Japanese language instruction and support with finding work, make it easier for them to obtain Japanese citizenship, and open the way for the second generation to obtain citizenship from birth. In order to tackle the above issues we would need the enactment of an immigration law, which would establish the idea of a Japanese-style immigration nation, and the enactment of a ‘basic law on social integration’, as well as an ‘anti-ethnic discrimination law’, which would encourage social integration and multiethnic coexistence.” (It appears that the Hatoyama Administration adopted the LDP position that Japan does not need an anti-discrimination law. Link.)

By adopting such laws, Japan’s national parliament would declare the move toward an “immigration nation” to be a solemn national goal. In order to oversee the implementation of such laws, Sakanaka would not rely on existing government agencies – he would create an independent “Immigration Ministry.”

“The Immigration Ministry would be a national administrative organisation with sole responsibility for all policies concerning the legal status of foreign nationals. It will be composed of the following three departments:

1) The immigrant and nationality policy department (deciding standards for accepting immigrants and standards for granting Japanese citizenship, executing consistent immigration and nationality policies)

2) The immigration control department (carrying out duties related to the immigration control of foreign nationals and the recognition of refugees)

3) The social integration department (implementing measures for encouraging the adjustment of foreign nationals resident in Japan to society, and conducting multiethnic education).”

A central image that continually reappears throughout Sakanaka’s book is that of “desirable” immigrants, people willing to work and study hard and even commit themselves to permanent residence in Japan and perhaps even citizenship. But what about the inevitable appearance of “undesirables?” With the firm assurance of a career immigration official, Sakanaka knows what to do: “we must thoroughly crack down on immigrants who try to enter the country illegally. We must take a stance of zero tolerance towards those who try to slip in through the back door. To do this we need to lay down a flawless immigration management system. If it does not function properly we cannot expect the public’s support for the immigration policy. Should the image of foreigners in Japan become linked with crime, terrorism and other undesirable qualities, the plan would be dealt a terrible blow. Also we would not be able to make a society of coexistence a reality. In order to avoid this it is important that we do not permit illegal entry and stay.”

8. “Immigration Social Workers”

Sakanaka recognizes that immigrants need help in adjusting to their new world. “Should we accept immigrants on the scale we require, the development of ‘immigration social workers’ to provide guidance and support for immigrants’ adaptation to Japanese society will become a pressing issue. We will require institutions for Japanese language education, facilitation of settlement, and providing assistance to victims of discrimination. The difficulty here lies in securing enough staff who are qualified instructors of Japanese as a second language, have proficiency in foreign languages, deep knowledge of both Japanese and non-Japanese cultures, and can operate in a variety of institutions.

“Across the country, there are about 20,000 people in Japanese language education field alone, and the staff of many non-profit organisations and volunteers already providing support to foreign nationals living in Japan. These non-profits work under diverse mandates, such as support for refugees, championing foreigners’ rights, the eradication of ethnic discrimination, and multiculturalism. The volunteers I have met have all been members of minority groups, people who work passionately to support foreign residents, social development, and bring about institutional reform. I have nothing but admiration for their endeavours. It is imperative that we, government and citizens alike, consider these people an indispensable resource for the age of immigration and nurture and support them accordingly.

“As for the question of how we are to supply these social workers. It is my belief that we must seek to obtain and develop individuals who work in the non-profit and volunteer fields. I suggest the government implements an ‘immigration social worker’ development programme. People who complete the programme will be officially recognised as social workers for immigrants and placed in a special register.”

Here it would appear that the author has struck pure gold. How to provide worthwhile employment to liberal arts and social science university graduates and others who have drifted into a tough fight for survival in the “freeter” world? Train them to become the social workers and language teachers needed to implement and facilitate a rational and humane immigration policy. Their country needs them to do much of the hard work of building Sakanaka’s multiethnic society.

Final Comment

There is wide recognition of Japan’s demographic dilemma and of the need for foreign labor. Sakanaka parts company with the consensus when he calls for permanent, not temporary, workers. In “Immigration Nation” he enumerates a list of policies and goals to be considered in assisting a move toward a multiethnic society. Does the Sakanaka program have a chance?

The irresponsible attitude displayed by Japanese authorities in their handling of South Americans of Japanese descent invited to Japan in the 1990s (See David McNeill, et al, “Lowering the Drawbridge of Fortress Japan: Citizenship, Nationality and the Rights of Children”) shows that a sea change in official and public attitudes toward immigrants must occur before Japan will be viewed as an attractive destination for most talented immigrants, “a country that gives dreams to foreigners.”

Glenda S. Roberts teaches in the Waseda University Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies. She is the co-editor with Gabriele Vogt of Migration and Integration, Japan in Comparative Perspective, forthcoming in 2011, Iudicium.

Lawrence Repeta is Professor of Law, Meiji University, a director of Information Clearinghouse Japan and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

Recommended citation: Lawrence Repeta and Glenda Roberts, “Immigrants or Temporary Workers? A Visionary Call for a ‘Japanese-style Immigration Nation,'” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 48-3-10, November 29, 2010.

Notes

1 The full text of the UN Human Rights Committee’s comment follows.

24. The Committee is concerned about reports that non-citizens who come to the State party under the Industrial Training and Technical Internship Programmes are excluded from the protection of domestic labour legislation and social security and that they are often exploited in unskilled labour without paid leave, receive training allowances below the legal minimum wage, are forced to work overtime without compensation and are often deprived of their passports by their employers. (arts. 8 and 26)

The State party should extend the protection of domestic legislation on minimum labour standards, including the legal minimum wage, and social security to foreign industrial trainees and technical interns, impose appropriate sanctions on employers who exploit such trainees and interns, and consider replacing the current programmes with a new scheme that adequately protects the rights of trainees and interns and focuses on capacity building rather than recruiting low-paid labour.

2 Numerous relevant issues are addressed in the contrasting essays by American and Japanese authors in Soft Power Superpowers – Cultural and National Assets of Japan and the United States (Watanabe and McConnell (eds.), M.E. Sharpe, 2008.) See Chapters 3 “Higher Education as a Projection of America’s Soft Power” and 4 “Facing Crisis: Soft Power and Japanese Education in Global Context.”