Koh Sunhui and Kate Barclay

Summary

Despite centuries of subjugation by larger neighbours—Joseon Korea, Imperial Japan, and South Korea—Jeju island society has maintained a distinct identity and a measure of autonomy. Relations with both Korea and Japan have at times had devastating effects on the islanders, but also contributed to the dynamism of Jeju island society and opened up new routes for islanders to continue traveling as a vital part of their social life.

Introduction

The centering philosophy of Chinese political culture (Zito 1997), in which space was imagined in terms of a centre and its periphery, contributed to the fact that island societies in northeast Asia, such as Jeju, were either ignored or dismissed as backwaters in the records kept by land-based larger powers on the Chinese mainland, Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago. The actuality of lively intercultural contact in the maritime areas through fishing, trade and travel was thus elided from the historical record [2]. In the modern era the centre-periphery political model has been replaced by the nation-state ideal. Nation-state ideology, which came to dominate political spatial imaginaries globally in the twentieth century, also acted to obscure travelling practices of maritime peoples, because in the normative system of nation-states, transborder communal identities are anomalous, and translocal ways of life existing across territorial borders are often treated as illegal.

Recent historical work has addressed these biases by turning the focus away from ‘nations’ to more local and regional social, political and economic entities, especially in (what we now call) China, Korea, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands (Wigen 1999; Kang 1997; Smits 1999) [3]. This paper contributes to that body of work by adding a new historical perspective; that of Jeju Island. The paper highlights Jeju’s contact with its two most significant neighbours, Korea and Japan, and is organized chronologically into Joseon Korea, the Japanese Empire, Cold War South Korea and the contemporary era.

Socially and culturally Jeju Islanders have been open to the peoples with which they came in contact, while the island was politically subordinated by its larger land-based neighbours. This openness, in conjunction with political subordination, did not mean that Jeju Islanders assimilated. Rather, they managed their political and cultural relations so as to maintain a measure of autonomy and cultural distinctness. This history of Jeju Island contributes to the understanding of the nation-state from the perspective of minority ethnic groups, especially those living across territorial borders.

Background

Jeju, made up of one main island with several small outlying islands, lies in the East China Sea, to the west of the southern part of the Korean peninsula, and north of Japan’s Kyushu. Jeju was first populated before the Bronze Age. In Jeju Island’s founding myth three men — Yang-ulla, Ko-ulla and Pu-ulla — are said to have sprung forth from the Three Sacred Caves. One day a king in Japan (which they called Pyongnang) sent an emissary with the king’s three daughters and five koku of seeds. The three mythic ancestors of Jeju Island are said to have married these three Japanese princesses, and with the five koku of seeds they founded the country [4].

Jeju’s original population has been added to by immigrants from China and the Korean Peninsula over the last thousand years. The waters around the island are rich in marine life, so fishing has always been a mainstay of the economy. Jeju was also one of the main hubs of the East China Sea trade routes from early times. It fell within the spheres of activity of the Ryukyu Kingdom (present day Okinawa) and the state called Yan in China’s Warring States period (323-222 BC) (Chun 1987). Around the period 14 BC to AD 23 the currency used by Jeju Islanders for maritime trade also circulated as far away as the Kansai region in Japan and the northern part of the Korean Peninsula (Chun 1987, 11-45).

From as far back as there is evidence of human habitation on Jeju Island, fishing was an important part of the economy. Archeological excavations of the island have found that fishing techniques in the Bronze Age involved boats and nets as well as coastal shellfish gleaning (Kim 1969, 138). Fishing as an aspect of Jeju society shares many historical connections with Japan. Japan and Jeju are two of very few places in the world where women have made a major part of their living by diving. From at least the fifteenth century Jeju women divers fished grounds around Jeju and the Korean peninsula. Japan’s Engishiki records that the tribute commodities presented to the Japanese Emperor by the countries of Higo and Bungo included ‘Tamla abalone’, a Jeju specialty (Amino 1994) [5]. Jeju Islander kara-ama [6] travelled to the Japanese archipelago in around 900AD (Miyamoto Tsuneichi as paraphrased in Amino 1994, 95; Chun 1987, 37). Japanese writings on Jeju always discuss the women divers of Jeju Island, and Japanese researchers have explored Jeju for the origins of women divers as a regional social phenomenon (Tanabe 1990, 708-709). This has led Habara Yukichi to assert that it is likely Jeju Islanders and “at least one group of Japanese” share cultural origins. He feels that observing the women divers of Jeju “is like looking at ancient Japan or the customs of the Yamatai Kingdom or the Ryukyu Islands and the Wajinden” (Habara 1949, 309) [7]. Jeju Islanders have also been represented as racially linked to Japan; Kim Tae Neung identified the indigenous Jeju people as “the same as the small people (indigenous Japanese) who are thought to have inhabited the Kyushu region of Japan” (Kim 1969, 140).

With a population of probably 10,000 – 20,000, Jeju was an independent country called Tamla for several centuries, until in 1105 the island was incorporated into the Korean peninsula’s Goryeo (AD918-1392) administrative district system. Politically Jeju was in a vassal relationship to Goryeo, and late Goryeo administrations used the island as a place of exile for political prisoners. For about a century, from 1273, Jeju was a demesne of Mongolia. Jeju supplied warhorses to the mainland and was also a place of exile for Mongolian criminals and Yunnan nobility.

In being simultaneously politically connected to both a government on the Chinese mainland and one on the Korean peninsula, Jeju was similar to another island society in this maritime region, the Ryukyu Islands, which also juggled relations with polities on the Chinese mainland and Japanese archipelago [8]. For these small island societies allowing the large land-based powers to claim political domination protected them from annexation attempts by other larger powers, but formal subordination to the land-based powers did not substantially affect the day-to-day activities of the islanders who retained functional autonomy.

Jeju’s status as a repository for exiles reveals that Jeju and its maritime world was viewed by its larger land-based neighbours as a desolate place for people from the centre (Chun 1987, 11-45). Ironically many of these exiles were prominent intellectuals from factions that had been on the losing side in power struggles, so through them culture and ideas direct from centres on the Chinese mainland and peninsular Korea diffused into Jeju society. But the (Neo-)Confucian imaginary, in which political and cultural civilization radiated out from centres of civilization, and agriculture was ranked over fisheries, made it difficult for the maritime areas to be seen as anything other than peripheral from the land based centres.

Since the only early written records are those in Chinese by Confucian literati, these biases peripheralizing the maritime areas permeate the historical record [9]. Factual inaccuracies arising from these biases include representations of Jeju Islanders as hostile to outsiders, when Jeju Islanders’ travelling social life actually necessitated amicable contact with outsiders (Chun 1987). Record-keeping literati overlooked Jeju’s history as independent Tamla, representing it as always already a marginal part of the polity on the Korean peninsula (Chun 1987). The dynamic cosmopolitan nature of the maritime areas between the land-based powers was thus omitted from history.

Joseon Era

Despite having been annexed in 1105 Jeju remained quite independent of the peninsula throughout the Goryeo period. Parts of the Korean peninsula such as Silla, Baekje and Goguryeo had also been independent countries prior to unification under Goryeo, but their proximity to each other as neighbouring parts of the peninsula facilitated effective centralization into one polity. Jeju’s geographic distance from the peninsula enabled it to remain a somewhat separate entity. At the end of the Goryeo period in the late fourteenth century Jeju islanders instigated uprisings led by people of Mongolian descent against Goryeo government control of the island. Early rulers in the Joseon (or Yi) Dynasty (1392-1910) saw it as important to subjugate and Koreanize Jeju (Takahashi 1991, 41).

Sejong, the revered fourth Joseon king to whom the establishment of the Korean Hangeul language is attributed, set about integrating Jeju more closely with the peninsula through its system of governance. He established on Jeju a branch of the Hyang Gyo national Confucian school (Yang 1992, 191-193). This generated a class of Jeju Islander Confucian scholar elites, who formed a Confucian bureaucracy on Jeju, which was headed up by a bureaucrat sent out from the peninsula. Jeju bureaucrats were also recruited to a special Jeju Island department of the administration in the capital (the city now called Seoul). Other policies tying island elites to the peninsula included assembling the children of island elites in the capital several times (from 1394 to 1428) and involving them in the state apparatus in capacities such as court bodyguard (Takahashi 1987, 68).

This system of governance, however, failed to completely integrate Jeju into the Joseon political system. One cause of continued segregation was that Jeju Island was not included in the system of the higher civil service examinations to enter the mainstream Joseon bureaucracy. Occasionally the first round of the exam was held on the island to offset the inequality resulting from geographical isolation, but not regularly enough to mainstream Jeju bureaucrats (Yang 1991, 98-99). Jeju bureaucrats mostly only worked with other Jeju bureaucrats, both on Jeju Island and in the Jeju department in the capital; they did not circulate throughout the administration as did other Joseon bureaucrats.

Another way Sejong’s Koreanization strategy maintained a level of segregation was that Jeju bureaucrats for the department in the capital were selected on the politically expedient basis that they were already leaders in Jeju society (Takahashi 1991, 41, 44). Instead of replacing indigenous authority structures, Confucianism was thus laid over the top of, and drew part of its authority from, indigenous authority structures. Indeed non-Confucian power brokers remained influential in many important local matters. Jeju leaders felt strongly that Jeju was a distinct polity under the Joseon administrative umbrella, so Jeju bureaucrats acted as intermediaries between the Joseon government and leaders on Jeju Island in ways that were designed to protect Jeju’s autonomy within the Joseon system. Koreanization policies that allowed Jeju Confucian scholars to become bureaucrats but then only to work in Jeju or in the special department in the capital, therefore, failed in important ways to reinforce the islanders’ sense of being part of the political entity and culture based on the Korean peninsula. The Jeju Island ruling elite accepted the Confucian thought that comprised Joseon political ideology, but had limited concrete experience of belonging to the same polity as the peninsular Koreans, and had vested interests in maintaining some measure of political autonomy.

Joseon attempts to Koreanize Jeju were limited not only in the extent to which Jeju Islanders felt assimilated, but also in Joseon identifications of Jeju Islanders. Some Jeju bureaucrats in the capital were greatly trusted by the kings of the time and rose to high prominence, being appointed to important official positions (Takahashi 1991, 40). These bureaucrats were regarded as part of the Joseon kingdom, but simultaneously treated as “people from overseas”. Jeju Islanders were seen by the Joseon kings as being neither Japanese nor “Yeojin” (Jurchen [10]), but as constituting another group also somehow different from the people of the central and southern Korean peninsula, as bureaucrats from the country of Tamla, which was loyal to the Joseon Dynasty (Takahashi 1991, 55 – 57). If bureaucrats and intellectuals who were educated in Joseon thought and were nominally part of the Joseon government did not feel properly “Korean”, the general Jeju populace felt even less so. Jeju was politically subordinate to Joseon, but the islanders maintained an identity as people of Tamla. They were engaged with the Joseon administration as subordinate, but at the same time maintained a measure of autonomy.

The peripheralization of Jeju in peninsula Korean perceptions is visible in representations of Jeju’s Confucianism. Despite the fact that a Confucian education and political system was established on Jeju Island at the outset of the Joseon era, Joseon recorders represented Jeju as lacking Confucian yangban culture (Choi 1984, 12). The literati yangban class in Joseon society was the group privileged to hold high ranking military and civil posts in the government. Schools tended to be located in consanguineous villages that had the critical mass of yangban families to sustain a school. Consanguineous villages were thus seen as the basis of dynamic and sophisticated yangban society. In Joseon Korea yangban culture, Confucian education, and consanguineous villages were all synonymous with civilization. Joseon record keepers were predisposed to see Jeju as uncivilized, so it is not surprising that these record keepers failed to recognize yangban Confucianism on Jeju.

Jeju yangban

It is a matter of historical record that there were Jeju scholar bureaucrats throughout the Joseon era, but could Jeju society as a whole be characterized as yangban culture? Chinju county and Andong county on the peninsula were famous for having many yangban families and consanguineous villages. Statistics compiled by early Japanese researchers as part of the colonial administration indicate that by the late Joseon era Jeju had at least as many yangban as these districts, and the proportion of scholars in the population on Jeju was as high as anywhere on the peninsula (Zensho 1935, 511; Zensho 1927, 96; Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1927, 113-114; Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1928, 514-515) [11]. Although being a Confucian scholar did not mean upward social mobility within the Joseon bureaucracy for Jeju Islanders, learning through village schools was connected to local power structures and it brought prestige within the island society, so competition to acquire education functioned in Jeju as it did in other parts of Joseon Korea, as an important stimulus to internal development in consanguineous villages (Yang 1992, 203). As on peninsular Korea, Jeju’s consanguineous villages were associated with the governing elite yangban and with Confucian education (Zensho 1935, 666). Jeju Confucian scholars did not mix and compete with scholars from elsewhere in the Joseon bureaucracy, so we cannot assume their education was the same, but because Jeju hosted political exiles we can assume that Jeju scholars were exposed to learning from the heart of Joseon yangban culture.

In addition to peninsula predispositions to see Jeju as uncivilized and the fact that scholar bureaucrats were segregated from the mainstream Joseon bureaucracy, another reason Joseon recorders may have failed to recognize Confucian yangban culture on Jeju was that it looked different to that on the peninsula. On Jeju it was not unusual for non-yangban men to become scholars. On the peninsula it was theoretically possible for non-yangban men (warriors, farmers, artisans, or tradesmen) to become scholars (Zensho, 1927, 96), but wealth based on land ownership was consolidated amongst yangban families, so in practice non-yangban did not have the means to enable their sons to become scholars. On Jeju land holdings were not so concentrated among the elite yangban group but tended towards families owning the small piece of land they cultivated (Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1929, 83). Income was thus more evenly distributed and it was feasible for non-yangban men to study (Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1929, 148).

Family and gender relations were also vastly different on Jeju compared to the peninsula. Families on the peninsula were usually extended, whereas on Jeju they were usually nuclear, with each generation setting up house on their own. Jeju women divers, which to outsiders symbolized Jeju women as a whole, worked outside the house, earning money independently, and wearing minimal clothing while diving. Their husbands stayed home looking after the children when the women were out working. Jeju women could own property and often kept their income individually, using it as they chose. Before marriage Jeju women often travelled away from home to work and save money. Peninsula yangban women were segregated from men at an early age; men worked outside the house while women worked inside. Indeed, yangban women could not freely leave their houses, especially before they married, and were clothed with extreme modesty from head to toe. Peninsula yangban women did not own wealth independently from their families, and their husbands or male relatives undertook all economic activities external to the house on their behalf. From the perspective of the peninsula, Jeju society seemed wild and uncivilized; the women seemed to have no sexual morals and the families appeared to have no structure. It was impossible for peninsula Koreans to conceive of civilized educated families allowing their women to behave as Jeju women did, so they concluded that there must have been a lack of civilization and education.

On the peninsula yangban society was associated with strict patriarchy, rigid hierarchies and great wealth differentials between socioeconomic strata. Since on Jeju gender relations were less patriarchal, wealth differentials less marked, and boundaries between socioeconomic strata more flexible, Jeju yangban culture looked different to yangban culture on the peninsula. Societies that adopted Confucianism did all not assimilate into some kind of homogenous cultural entity; rather Confucianism varied according to the social and cultural context in which it was adopted. Confucianism was imposed on Jeju by the Joseon polity to which the island was subordinated. It was, however, then indigenised and adapted to local social conditions. Not all aspects of Confucianism were altered through adaptation on Jeju in the same way as the educational political systems. Confucianism as it pertained to weddings and funerals was preserved for hundreds of years in virtually the same form as it was first adopted, without being noticeably localized (Kaji 1993) [12]. One of the major features of Jeju culture affecting their indigenisation of Confucianism was the fact that Jeju was a maritime society. Confucianism in other places was a philosophy of sedentary, agricultural, land-based society, but on Jeju it became the philosophy of a travelling maritime society.

Kaijin: Maritime Confucians

One way to think of the network of societies across the seas of the northwestern Pacific Rim is to think of them as sharing an identity as kaijin, sea people. The Japanese term kaijin as used by Tanabe Satoru refers to divers, fishers, salt manufacturers, and people who lived and traveled on boats; in short all men and women whose lives involved the sea (Tanabe 1990) [13]. From the perspective of a maritime society the sea is not a boundary that separates societies, but a force that connects them [14].

Jeju Island’s geographical location between the Korean peninsula, Japan and the Chinese mainland made it a point of contact for peoples from all these places in medieval times. Jeju Islanders moved outwards from their island base, and people from various places came across the sea to Jeju (Takahashi 1992, 169). According to Takahashi in the early centuries of the Joseon era Jeju Islander kaijin were called Todung Yagi. Takahashi’s study of records places the Todung Yagi traveling through the East China Sea, the Yellow Sea, as far south as Hainan and as far north as the Sakhalin Islands from the fifteenth century (Takahashi 1992, 177-181) [15]. More than twenty Jeju families were recorded as living on Herang Island, which lies on an extension of the boundary between Pyongan Province and the Liaodong Peninsula and which was at the time Ming territory. The Jeju Islanders on Herang were engaged in (illicit) trade with kaijin from Ming territory (Takahashi 1992, 185-186). Several thousand Todung Yagi were documented as appearing in the coastal areas of the peninsula in the Jeolla and Gyeongsang provinces and Sachon, Kosong and Chinju during Sejong’s reign (1418-50) (Takahashi 1992). The population of Jeju Island (including Jeju-mok, Jeongui-hyeon and Daejeong-hyeon) around this time was recorded as 18,897 (Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1927, 40). Censuses were carried out on an irregular basis during the Joseon Dynasty and their accuracy is questionable, however, if “several thousand” were moving around Jeolla and Gyeongsang this suggests that a high proportion of the population was mobile.

The Todung Yagi’s clothing was described as being similar to that worn by Japanese, and their language was described as being neither Japanese nor Chinese. Their boats were described as fast-sailing and sturdier than Japanese boats and their recorded occupation was diving for abalone. They lived a mobile life from their boats, always in search of the best fishing grounds. Abalone was an important tribute commodity so the Jeju abalone divers were protected, but it was noted that if attempts were made to regiment or control the divers they simply moved on. The land based powers surrounding the maritime area of the northwest Pacific Rim had limited influence in the coastal and sea-going world the kaijin inhabited (Takahashi 1992, 171). Their very mobility made it difficult for administrative authorities to extend control over the kaijin.

Records of shipwrecks trace the movements of Jeju kaijin. Jeju islanders were recorded as being shipwrecked in the Goto Islands, the Tokara Islands, the Ryukyu Islands and Chinese coastal areas (Takahashi 1992, 188). Kaijin met up with each other and interacted in this coastal world through shared aspects of kaijin culture. They built up relations of trust not constrained by territorially bounded political entities. The identification with Japan visible in Jeju Island’s founding myth shows that Japan has long been envisaged as part of Jeju Island’s cultural sphere. Jeju Islander identification with Japan may be seen as a form of regional kaijin identity. According to Takahashi, Jeju islanders who had been shipwrecked in the Ryukyu Islands expressed their gratitude for the kindness of the Ryukyuans in ways that identified with the Ryukyuans as fellow kaijin, rather than as Koreans or people of Tamla relating to the Ryukyuans as foreigners (Takahashi 1992, 193).

Sixteen shipwrecks (ten Japanese and six Qing ships) were recorded on Jeju between 1848 and 1884 (Koh 1993). One Japanese ship departed from Hirado Island in what is now Saga Prefecture, four from the port of Kagoshima, two from Satsuma castle town (in what is now Kagoshima City), two from Tsushima and one from the Abu district in what is now Yamaguchi Prefecture. One Qing ship departed from Guangdong, three from Jiangnan, one from Shandong, and one from Zhejiang, that is from provinces ranging from north to south coastal China. Most of these boats had been engaged in trade, with the remainder engaged in fishing, piracy, searching for missing people, or the transport of tax monies. The Japanese ships carried Japanese and Ryukyuans, while the Qing ships carried peoples of coastal Chinese groups, as well as French and Russians trading in the area. The kaijin world of the northwest Pacific Rim in the later half of the nineteenth century was multicultural indeed.

Shipwrecks on Jeju were reported by the Jeju Island bureaucracy to the central Joseon bureaucracy. The Jeju policy was to provide shipwrecked people with provisions, clothing and fuel. On receiving word of a shipwreck, local bureaucrats set out with interpreters to investigate and provide assistance as needed. People from the nearest village prepared warm food, and provided survivors with clothing and shelter. Funerary rituals were performed for dead bodies washed ashore. In offering hospitality to shipwrecked people Jeju Islanders hoped the survivors would talk about Jeju favourably on their return home, to ensure Jeju Islanders would be similarly well treated when they were shipwrecked in their travels [16].

But the kaijin world was not all cosmopolitan harmony. Piracy was an ongoing problem. Kang (1997) cites numerous records of the Joseon government raising the wako piracy issue with Japan, which was seen by the Joseon administration as not being tough enough on the pirates operating along their coastline. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries trade and fishing treaties were signed between the Joseon administration and Japanese officials as part of Joseon attempts to suppress wako pirates. The policy was partly successful in that purely piratical activity declined, but enterprises that were a mixture of piracy, trade and fishing correspondingly increased (Yoshida 1954, 79-81). In addition, there was competition over fishery resources. From the late Goryeo period many Japanese lived in Busan, one of the major trading ports on the Korean peninsula (Yoshida 1954, 80). In 1418 permission was given by the Joseon King for Japanese people to reside in certain areas in waegwan (literally “Japan house”, meaning walled compounds for Japanese) in Gampo in Ulsan County and Karyangjin in T’ong Young County. In the same year the ports of Chaepo, Busan and Gampo were opened and waegwan established there, Japanese were given permission for fishing from these ports. Meanwhile, Japanese from Tsushima had established settlements in the Koje Island area, where they were involved in agriculture, fishing and the salt industry. They also traveled to other areas on the southern Korean peninsula.

Japanese fishers did not fish only within the approved area from the three port bases but traveled as far as the coasts of Jeolla and Chungcheong. Some Japanese fishing boats were armed and engaged in piracy as well as fishing (Yoshida 1954, 81). Tsushima fishers were given conditional fishing permission by the Joseon government in 1441, perhaps because the government realized that if they were not permitted to fish they would resort to the use of force (Yoshida 1954, 83). Most problematic of the Japanese fishing activities were those in the waters at the southwestern tip of Jeolla Province. This area was a treasure house of marine resources, and many fishers from the Korean peninsula also operated there (Takahashi 1992, 174). Japanese fishers repeatedly breached their agreements with Korea, both through illicit fishing outside the permitted area, and through piracy. Japanese fishers, especially abalone divers, were known for poaching around the southwest of the Korean peninsula, mainly Jeju (Yoshida 1954, 91-92). In 1608 a bilateral dispute arose from Japanese fishers involvement in violent incidents outside the area permitted under the treaty on the western side of the Korean peninsula (Yoshida 1954, 83). Problematic relations with some Japanese kaijin throughout the Joseon era presaged more serious competition over marine resources during Japan’s subsequent colonial expansion.

Japanese Empire

First Phase of Japanese Imperialism: Competition in Fisheries

Although Korea was not formally a Japanese colony until 1910, for the purposes of this paper imperial encroachments began much earlier, in the 1870s, when Japanese fishers started coming to Jeju Island in significant numbers (Yoshida 1954,159; Fisheries Bureau, Agriculture and Commerce Division, Office of the Governor-General of Korea 1910, 283). Since Japanese fishers from Tsushima in particular were unofficially operating off the Korean coastline since medieval times, we assume that Japanese fishers were visiting Jeju during the Joseon period. Jeju Island was a highly attractive fishing spot for Japanese fishers, being a major producer of abalone, turbin shells, bêches-de-mer, and abundant in species of fish Japanese consumers prized, such as bream (Kuba 1978, 169; Yoshida 1954, 207-208). Nakaya Tarokichi sailed with a group from Saganoseki in Oita Prefecture via Goto and Tsushima in 1870 (Yoshida 1954, 159). Takenouchi Genkichi from Nagasaki collected abalone from Jeju in 1874 and 1875 (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, p. 283). Kuba Gokuro’s oral history includes a Japanese fisher who remembers his older relatives going to Jeju to fish for bream in 1877 (Kuba 1978, 169). According to one Japanese fisherman “long before the end of the war about one quarter of all Japan was apparently making money from Jeju Island—a whole quarter of all Japan. That’s what I’ve heard. There’s probably nowhere in the world with such rich fishing grounds as Jeju Island” (Kuba 1978, 190).

When this wave of Japanese fishing commenced, the coastal reefs around Jeju were said to have been covered in abalone, with some weighing over 800 momme (1 momme = 3.75 grams) apiece. Japanese fishing boats were equipped with air compressors and hoses for breathing under water, which meant they were devastatingly effective. Japanese divers had started using underwater breathing equipment around Nagasaki. They quickly over harvested, leading to resistance from local villagers, and it was against Japanese regulations in any case, so they moved on to new coastlines, including Jeju (Yoshida 1954, 207-208). Yoshimura Yozaburo from Hagi in Yamaguchi Prefecture, thought to have been the first Japanese fisher to use underwater breathing gear in Korean waters, commenced operations in the vicinity of Jeju in April 1879 (Yoshida 1954, 207-208). Jeju Islanders were no happier with the depletion of their resources than the Nagasaki villagers had been, so at first Japanese diving boats were refused landing rights in Jeju, and they had to base their operations in Tsushima.

Japanese fishers were armed on the pretext of defending themselves against pirates, but the distinction between pirates and fishers was far from clear. Japanese fishers frequently used arms against locals who resisted them. In the words of a Japanese fisher from this time: “I think it was after the Russo-Japanese war in the Meiji period … we used dynamite to catch fish [a practice prohibited in Japan at the time], and we argued with the Koreans. We were running wild like pirates” (Kuba 1978, 128). According to another: “Ku-Ryong-po was another world … It was a place where there were hundreds and thousands of ex-criminals. From all over Japan … Every morning there were three or five people lying dead on the road” (Kuba 1978, 172-173).

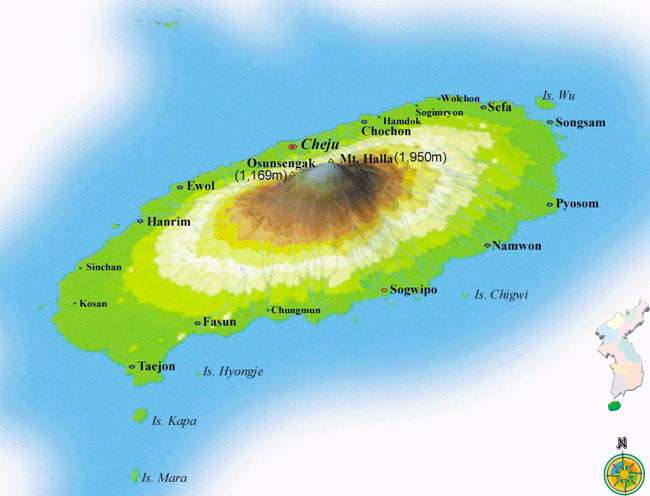

Map of Jeju (Cheju) Island

Japanese government records note disputes on Gapa Island off Jeju resulting in the death of one islander and injuries to several others (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 300). Japanese records note that Japanese fishers frequently went to Gapa Island for abalone fishing, but they also forcibly entered people’s houses, raped women, killed dogs, stole vegetables, took chickens, and threatened people with their swords. Some Japanese fishermen organized into armed bands of up to 200 to force islanders to obey them (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 304). Occasionally islanders were killed. More than 300 families were recorded as having left Gapa Island because of these incidents (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 304-9). The island was then used by the Japanese fishers as a base. Other islands off Jeju, such as U Island and Biyang Island, became Japanese fishing bases under similar circumstances.

A fishing access treaty between Japan and Joseon Korea was signed in 1883. After this the numbers of Japanese fishers in Korean waters rapidly increased. Diplomatic and trade relations between Japan and Joseon Korea in the Meiji era were formally established with the Korea-Japan Friendship Treaty concluded in March 1876, but this treaty contained no agreement on fishing. Japanese fishing in Korean waters was formalized after the implementation of Article 41 of the Japan-Korea trade regulations agreed on in July 1883 (Yoshida 1954, 160). By 1884 Jeju Islanders were suffering extreme economic hardship so they sought to have Japanese fishers banned from their waters. First they appealed to the Joseon Governor (Moksa) of Jeju, but he had no authority over Japanese fishers, so several tens of Jeju Islanders went to the capital to appeal directly to the Joseon government (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 17, 377-9). They managed to convince the Joseon government to take up their case with the Japanese government, arguing that Jeju Island should not be included the fishing treaty of 1883 that permitted Japanese fishing in four provinces—Jeolla, Gyeongsang, Gangwon, Hamgyõng. The Japan side contended that it was absurd to claim that Jeju was not part of Jeolla Province (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 17, 379), but eventually agreed to exempt Jeju from the treaty in exchange for mining patents on the peninsula (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 308-309).

Japanese fishers, however, ignored Jeju’s exemption from the fishing access treaty. They stopped using the bases they established on Jeju and based themselves at Tsushima, but continued to fish around Jeju. They also continued attacking Jeju Islanders. Islanders protested locally and lobbied in the capital (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 300). The Joseon government made repeated requests that Japanese fishers should respect the ban on fishing around Jeju but the Japanese government refused to acknowledge that their fishers were flouting the ban. Indeed, Japanese fishers took advantage of their government’s position by asking their government for compensation for lost fishing due to the ban. (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, 263). Furthermore, in 1891 the Japanese government proposed lifting the exemption, saying Jeju Islanders had enjoyed several years free of competition from Japanese fishermen and that Japanese fishermen had been warned against violence (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol 23, 263, 267). But then it became clear that another Jeju Islander, Yang Jong Shin, the port official at Pae-ryung-ri (present-day Kum-rung-ri), had been killed by a Japanese fisher in 1890 (Kim 1987, 161). So the Japanese government agreed to extend the exemption by a further five months, but the situation did not improve. In June 1891 Yim Soon Baek from Keonip-po was murdered, and in July Yi Tal Kyum from Kim Nyong Ni was killed and 17 other people were wounded.

According to the records of the Jeju Governor of the time, the violence and economic hardship brought about by the Japanese fishers had brought the islanders to a state of “indescribably extreme wretchedness” (Kim 1987, 161). After the murder of Yang from Pae-ryung-ri, more than a hundred Jeju Islanders went to the capital and petitioned the Joseon government to enforce the ban, arguing that Jeju could not support itself or continue to provide abalone for tribute if over-exploitation of their fisheries by Japanese fishers were to continue (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, 285) [17]. Considering transport methods and costs at that time, the expedition of more than a hundred people to the capital to lobby the government was an extreme measure. The Islanders were desperate.

Despite continuing violence, the Japanese government unilaterally lifted the nominal exemption of Jeju from the fishing access treaty in 1892, after which violence and forced occupation of small islands off Jeju by Japanese fishers escalated. In April 1892 Japanese fishers called Yamaguchi and Koyanagi led 144 fishermen to build a base at Seongsan on Jeju Island. As a result of this occupation many women were raped and a villager called Oh was shot (Kim 1987, 163). A group of islanders went to the capital and called on the administrative official to have the huts removed (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, 371). In this instance their demands were successful, and the huts were (temporarily) removed. Around the same time two men from Hwa Buk, Kim and Koh, were murdered, and in June two people from Tu Mo-ri by the name of Koh were killed. Armed Japanese fishermen attacked Jeju Islanders many times that year.

While all this was going on Japanese naval vessels patrolled the waters around Jeju Island. The main reason for the Japanese naval presence was concern for possible harm to Japanese fishers and traders, because of a belief that Jeju Islanders were a militant barbaric people (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 302). The Japanese government’s views on Jeju Island reflected those of the Joseon government towards Jeju, and were exacerbated by the Japanese government’s own bias regarding Koreans and the inhabitants of islands they saw as “remote”. Contrary to Japanese government beliefs, however, Jeju Islanders did not respond violently to the Japanese fishing incursions they were trying to prevent. When Japanese government officials investigating complaints against Japanese fishers suggested that the islanders used violence in an attempt to get rid of Japanese fishers, the Japanese fishers themselves rejected this suggestion, saying: “no such thing occurred” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, 393-394). Japanese fishers said after the murder at Seongsan in 1892 a Jeju Island official had given the Japanese fishers a verbal instruction to remove their huts by a certain time, as has happened earlier with the huts on Gapa Island (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, 390). Japanese fishers said that they did not usually comply with these instructions and then the Jeju bureaucrats’ course of action was simply to come and repeat the verbal instructions, about every two weeks (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, 393-394).

And where Japanese fishing activities were peaceful Jeju Islanders responded to the fishers as openly as they always had to travelers. Takenouchi Genkichi from Nagasaki, who started traveling to Jeju Island to gather abalone in the mid 1870s, said that between 1887 and the murder of Yang in 1890 there were very few incidents in the areas of Jeju he frequented, and that relations between Japanese fishers and Jeju villagers were amicable. Jeju bureaucrats prohibited any support of Japanese fishing activities because it was their position that the fishing was illegal, but Japanese government records contain several references by Japanese fishers saying that Jeju Islanders provided water and fuel to Japanese fishers (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, 284).

The strategies employed by Jeju Islanders to resist incursions by Japanese fishers demonstrate that Jeju Islanders still felt themselves to be an autonomous polity within the Joseon administrative system. After the escalation of Japanese fishing activities on Jeju following the fishing access treaty of 1883, locals realized their local Governor had no power over the Japanese fishers and went to the capital to lobby the Joseon government. They approached the important pro-modernization figure Kim Ok Kyoon, who had close ties to the Japanese government, and persuaded him to take up their case (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 17, 378-379). Islanders who had never been to the capital before were unlikely to have chosen such a canny target for lobbying, so it is likely they were advised by Jeju Islander bureaucrats in the Jeju Island department in the capital. Other coastal areas of the peninsula were suffering similarly from the onslaught by Japanese fishers, but none of them were granted a fishing treaty exemption. Jeju Islanders agitated so effectively they not only had the Joseon government demanding that Japan put an end to fishing in Jeju Island waters in August 1884, but that the whole fishing access treaty be reviewed because the benefits and costs of the treaty were unequal (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 17, 381; Kim 1987, 159).

Kim Ok Kyoon’s actions show that within late Joseon Korea Jeju was still considered somewhat autonomous. He accepted the lobbying Islanders’ position that they were not part of Jeolla Province but were a separate polity under the Joseon administration. Kim negotiated with Japan on this basis. Other government representations also show that Jeju was not seen as fully Koreanized or fully under the control of the Joseon administration. Joseon officials declared to Japanese officials that “compared with home [the Korean Peninsula], the people of Jeju are obstinate and difficult to reprimand” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 22, 376). A document from the Joseon government to Japanese fishers intending to fish around Jeju read: “Greetings. Fishing at Jeju Island in our country is not permitted—they are not yet civilized people, so will not obey orders from the our government.” The statement locates Jeju inside “our country” but also refers to Jeju islanders as distinct from Joseon Koreans in that they are “not yet civilized” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 23, 267). The Meiji Japanese government held a similar view that “the customs of Jeju differ from those in [peninsular] Korea, the people are obstinate and do not obey government orders” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Vol. 20, 301).

During this first phase of Japanese imperialism Japanese fishing incursions had the greatest impact on Jeju. Jeju Islanders’ strategies to cope with this onslaught included non violent and persistent official protests against Japanese fishers on Jeju, while unofficially trading with some Japanese fishers. They engaged with the Joseon administration as an autonomous polity loyal to the Joseon Dynasty, and were recognized as such, but ultimately were unable to protect their fishing grounds from Japanese fishers. As they lost this struggle their engagement with Japan moved into a new phase.

Second Phase of Japanese Imperialism: Wage Labor Migration

As Japan moved closer to annexation in 1910 Japanese fishing operations came to thoroughly dominate fishing all around the Korean peninsula. In 1899 there were 25,000 people working on approximately 1,000 Japanese fishing vessels along the coast of Gyeongsang and Jeolla provinces alone (Mountains and Forests Bureau, Agriculture and Commerce Ministry of Japan 1905, 28). The fishing was very good around the Korean peninsula; in 1908 the annual fish catch in Japanese waters was on average worth no more than 40 yen per person, whereas around the peninsula the average for Japanese fishers was over 195 yen, and Joseon Koreans averaged more than 45 yen (Yamaguchi 1911, 182). The fish catch from the colony of Korea grew ten-fold in the twenty-seven years following Japan’s annexation, and the catch of sardines in Korea multiplied eleven-fold in the six years between 1932 and 1937 (Aono 1984, 238). Japanese divers, mostly from western Japan, put in a great amount of effort, with 120 boats setting out in 1893, increasing to 400 by 1907 (Yoshida 1954, 207-208). As a result fishing grounds such as Jeju Island and So An Island were exhausted. Jeju Islander fishers and divers were pushed further afield to make ends meet.

At the same time, Japanese traders were buying marine products from Jeju fishers and divers, and selling them Japanese products. This meant that Jeju Islanders, who had previously been largely self sufficient, became ever more deeply enmeshed in the cash economy. This marked a new epoch. In their new weakened economic position Jeju fishers went from being self employed to being the employees of Japanese companies, with lower wages than Japanese nationals. The empire thus subjugated Jeju Islanders, but also opened new opportunities for wage labor migration in Japan.

Jeju women divers joined male and female diving groups from various parts of Japan working the along the Korean peninsular coast (Kuba 1978, 205). When the colonial Korean fishing ordinance was enacted in 1915 the Jeju women divers’ union acquired fishing rights along the entire coast of the peninsula (Masuda 1986, 67, 83). The Jeju women divers received lower wages than the Japanese divers and were very productive, so by the early Showa period no Japanese divers were working the Korean coast. Japanese divers from Ise had been working the Korean coast at Pang Oe Jin in Gyeongsang Province and Pohang (Jeong Ja-ri) in Ulsan County since the mid 1800s, but after the Jeju divers went there in significant numbers in 1895 the Ise divers disappeared (Masuda 1986, 82).

Stories from Japanese people show the extent of the personal contacts being made across the region through Japanese colonialism. One Japanese fisherwoman had her first baby at her head family’s house, her second at an inn in Korea, and her third was born in Dairen (Kuba 1978, 183). Despite the colonial structure within which these personal relationships took place, they were often characterized by openness and mutual respect. A young Korean man jumped in to save a Japanese fisherwoman working in Korea who fell from a boat with her infant tied to her back (Kuba 1978, 198). When a Japanese fishing boat ran into pirates in Korean waters and most of the crew were killed, the only survivors were “a kind-hearted Korean mother [who] took a [Japanese] child on her back and ran away… We saw that child ourselves. And the Koreans were so good as to arrange funerals in their village” (Kuba 1978, 130-131). By 1911 fishing ventures were employing Koreans regularly and often took Korean people back to Japan (Kuba 1978, 185). These Korean workers included children, some of whom were reportedly abducted, others had been sold as domestic servants or fishing laborers by poverty-stricken parents (Kuba 1978, 131).

Jeju Islanders were part of this flux of people throughout the Empire. The earliest record of seasonal cash work in Japan by Jeju women divers is from 1903, when several went to Miyakejima. The earliest record of Jeju fishermen engaging in wage labor migration is 1910, when over 100 fishers arrived in Japan as crew on Japanese boats (Masuda 1986, 83, 108). Jeju Islanders were hired for the season’s fishing by Japanese fishing boats and went with the boat wherever the fishing took them; the Korean peninsula, Dairen, or Qingdao. When the boat was ready to return to Japan it stopped off at Jeju, setting down the islanders who wished to return home. Islanders who wished to go on to Japan simply stayed on the boat for the final night’s trip (Kuba 1978, 185-7).

Under the Japanese Empire Jeju Islanders’ travel and work settled into a pattern of seasonal work for cash away from the island, interspersed with time on Jeju doing other things. By 1915 women divers were spending six months or so out of every year away doing cash work (Eguchi 1915, 168). Jeju Islanders also spent periods of several years engaged in manufacturing and trading away from Jeju before returning home, while others remained on the island working in agriculture, fisheries or commerce (Fisheries Bureau 1910, 441). Given their long history of migratory kaijin lifestyles, it was not difficult for Jeju Islanders to adjust to this pattern of seasonal work away from home, and soon they branched out into new kinds of work available in the Japanese Empire.

Modern Japanese cities were an alluring prospect for young Jeju Islanders curious to learn about the world. Japanese recruitment of industrial laborers from Jeju Island started in 1914. They went particularly to Osaka but also to the Hanshin industrial belt and Kita-Kyushu. There was a shortage of labor in these areas and the practice of hiring Jeju Islanders was already established in the fisheries sector. Industrial labor migration was behind the establishment in 1922 of a regular ferry service between Osaka and Jeju called the Hansai ferry. There had been regular ferry services between Korea and Japan prior to that, but these were mainly a means of travel for Japanese. By contrast, the Osaka-Jeju service clearly functioned as a means of bringing Jeju islanders to and from Japan. Prior to the establishment of this route Jeju islanders moving to Japan had used the Kampu ferry between Shimonoseki and Busan, or fishing boats. The opening of the regular Osaka-Jeju service made it easy for islanders to move to Japan to work. By 1934 twenty-five percent of Jeju Island’s population resided in Japan (Masuda 1986, 111).

Although Jeju Islanders’ early efforts at resisting Japanese incursions into their fishing areas failed and they moved on to adapting to the new political situation, more bursts of resistance against Japanese rule followed in the 1930s (Yang 1996). Jeju’s women divers played a key role in some of these movements (Fujinaga 1989). By then they had fishing rights to the whole Korean peninsula and were used to organizing themselves economically, so although they had no formal schooling, it was a small step for them to form groups to actively agitate for change in areas where their rights were abused.

Contemporary Jeju women divers

During the second phase of Japanese Imperialism over the first half of the twentieth century Japan had become an important place in Jeju Islanders’ translocal regional way of life. This posed significant problems for Jeju Islanders during the next historical phase examined in this paper, following the defeat of Japan, when South Korea was established as a postcolonial independent state and the Cold War started.

The Cold War

The Cold War brought about severe repression of Jeju Island within the Republic of Korea established in the south. Because of the historical nature of their engagement within the Japanese empire, which varied in important ways from other Korean experiences of being colonized, Jeju Islanders had complicated and shifting allegiances in the first few years after World War II, as the two Korean states came into being in a divided Korea. Jeju Islanders living in Japan were concentrated around the Kansai area and worked mostly in factories, whereas peninsula Koreans tended to work in construction. The Kansai factories were a hotbed of trade union activism in the decades leading up to World War II, in which Jeju Islanders participated. Some Jeju Islanders were active members of the Japanese Communist Party. Because the levels of education on Jeju were high and because many Jeju Islanders had the opportunity for schooling in the colonial system, the Jeju people in Japan were able to read newspapers and adapt to Japanese society quite easily. The peninsula Koreans in Japan tended to have less schooling and lived in communities that were more segregated from wider Japanese society. Before the war most of Jeju intelligentsia spent periods of time in Japan experiencing life in the big city and soaking up the newest ideas about social organization to take home to Jeju, including left wing ideas (Koh 1996b, life history volumes). At the same time, while Jeju Islanders had long fought for autonomy under the umbrella of the Joseon administration, Jeju Islanders felt allegiance to the peninsula as a polity, and were excited by the possibilities of an independent modern Korean state. Many Jeju Islanders felt strongly that the new Korean state should be unified, not divided by foreign powers, and the influence of left wing ideas in prominent families meant that many Jeju Islanders also strongly identified with the communist regime in the North [18]. Again, Jeju Islanders did not simply accept an unsatisfactory state of affairs but agitated against south-only elections. Some left wing groups took up arms left behind by Japanese military forces that had been based on Jeju.

US military advisors, in the context of the unfolding Cold War, supported the South Korean military and police in brutal retaliation against the islanders’ opposition to the elections. This occurred on 3 April 1948, and is often referred to as the 4/3 Incident (forth month, third day). It is difficult to know exactly how many people were killed, because the population of Jeju in the post war years is unclear. Many people had returned from Japan, and many of these then moved on again, but it is likely the population was around 300,000. Local records show 14,028 people were registered as killed or missing that day, and since many more deaths would not have been registered it has been estimated that 20-30,000 people were killed (Jeju 4/3 Research Institute 2005). A Korean security officer is reported to have said of Jeju at the time “if it’s for the good of the Republic of Korea, sprinkle gasoline over the whole island and wipe out all 300,000 in one go” (Jeong 1988, 61).

The South Korean military dictatorship was not only rigidly anti-communist, anti-Japanese anti-colonial sentiment was an important part of nation building in postwar Korea. In the immediate post war it was not easy to be clearly anti-Japanese because most of the Korean ruling class had been educated in Japanese language, many in Japan. Nevertheless overt continuing connections to Japan were frowned upon. This had an effect on Jeju Islanders. As mentioned earlier, Jeju Islanders identified with Japanese as fellow kaijin. In addition, during the colonial era Jeju Islanders had established more connections to Japan through work, study and travel in the colonial period than other peninsula Koreans. Many of the islanders who settled in Japan before the war remained afterwards; proportionally Jeju Islanders made up a significant part of the ethnic Korean population who chose to continue to live in Japan after the war. Families with members living in Japan were seen as potentially traitorous by other Koreans, and many Jeju families fell into this category. Because of these close connections to Japan, as well as their suspected communist sympathies, Jeju Islanders were subject to surveillance by the South Korean government until the 1980s.

One of the life histories researched by Koh Sunhui (1996b, life history volumes) demonstrates the complex interaction of connections to Japan and communist sympathies that meant Jeju Islanders were viewed with suspicion by the South Korean regime. This Jeju man was an activist in the labor movement in Japan in 1928, becoming a member of the Japanese Communist Party in 1948, and continuing with left wing activism until the 1980s. He visited North Korea three times via ‘illegal’ routes. He assisted his younger brother to go from Jeju to Osaka (without a visa) and from there to North Korea to live. Arrested three times by the Japanese government for his activities, he spent time in prison, then was repatriated to South Korea. After his last visit to North Korea in 1980 he switched allegiance from the North to the South. Still, a committed socialist, he began supporting South Korean policies regarding zainichi Koreans in Japan and strengthening connections to his home village on Jeju, eventually taking South Korean citizenship.

Contemporary Jeju Islander Identities

Anti-communist nationalism and modernization in the later half of the twentieth century brought about a greater degree of Koreanization of Jeju Island society than had been achieved by the Joseon administration. The authoritarian South Korean government imposed an official version of anti-communist Korean national identity on the islanders. Many aspects of culture that differed from those of peninsular Korea, such as local language, were suppressed and were not transmitted to younger generations. Mass education, mass media, economic development, the military draft system, and increased visits to and from the Korean Peninsula as a result of improved transport, all contributed to Koreanization. Bureaucratic centralization was strengthened under the military regime and rapid modernization was effected. More recently the South Korean government has moved towards decentralization, and there has been heightened interest in Jeju culture amongst Jeju Island public officials, the media and researchers. The strong devaluation of Jeju identity and culture during the post war military regime, which was internalized by Jeju islanders, has to some extent been recouped since the early 1990s.

The forceful Koreanization of Jeju during the Cold War pushed islanders beyond their historical cultural predisposition of openness to other societies, closer to assimilation. In the post war era Jeju culture came to be less distinct from culture on the peninsula. This is evident in a comparison of post war Jeju Islander identities. Contemporary Jeju Islanders see themselves as belonging both to Jeju Island—their country—and to peninsular Korea—their state. Which identity is foremost depends on the situation. In relations amongst themselves Jeju islanders identify as belonging to the same country. In relations with Koreans from the peninsula, Jeju Islanders identify as belonging to the same state, while recognizing that there are cultural differences between themselves and other Koreans, and while recognizing that their status within Korea is stigmatized (Koh 1998a and 1998b). In some senses this dual identity is similar to the identity we have traced since annexation just before the beginning of the Joseon era. But when we compare Jeju Islanders who have lived on Jeju in the post war era with Jeju Islanders who left before the war and have since lived in Japan, the effects of political changes in Korea during the post war era on Jeju identities are revealed.

Jeju Islanders who went to Japan before World War II and stayed there, and their Japan-residing descendants, exhibit a vague and abstract sense of Koreanness. They have some sense of belonging to Korea due to having been regarded since the end of World War II as “Korean residents of Japan” by Chongryon (General Association of Korean Residents in Japan representing communist North Korea) and Mindan (Korean Residents Association in Japan representing South Korea), as well as by the governments and people of Japan, North Korea and South Korea. So if you ask these Jeju Islanders what their ethnicity is they usually answer “Korean”. But in interviews nearly every time they referred to “Korea” they were actually referring to Jeju Island. When asked about Jeju Island and what it means to be from there, their answers are detailed and acute, but when asked about peninsular Korea and what it means to be a Korean citizen their responses are vague [19]. Islanders who have spent significant spans of time on Jeju in the post war era, however, have a much more concrete sense of identity with peninsular South Koreans, because of shared experiences in the education system, in military service, via the mass media, and so on.

Despite a certain amount of Koreanization, however, Jeju Islanders continue to exhibit an autonomous communal identity in their traveling practices. Contemporary Jeju migrants do not simply merge into local immigrant Korean communities but recreate their version of Jeju society wherever they are, by socializing together, and through establishing Jeju Island homeland societies. The homeland societies are not a strategic form of identity politics to distinguish Jeju Islanders from Koreans, since most Jeju Islanders consciously identify as Korean. Nevertheless, Jeju migration practices, including the homeland societies, sustain them as distinct from both mainstream Korean migrant groups and their host society (Koh 1998b).

Within contemporary imaginaries historical perceptions of Jeju Island as peripheral and uncivilized remain salient. One manifestation of this is that contemporary peninsular Koreans still tend to view Jeju Islanders as uneducated. Misinterpretation of different social educational practices have continued through the modern era. In Joseon peninsula Korea, as mentioned earlier, academic achievement was the only path to wealth and power. Education was thus unambiguously linked to material gain, and the cultural values surrounding education reflected the importance to strive for the highest formal qualification possible. In contemporary Korean culture this is played out in credentialism; a competitive drive to achieve formal academic qualifications. For Jeju islanders, however, academic achievement has historically not been the only criteria for social status, and in any case socioeconomic hierarchies were not so pronounced on Jeju. For these reasons Jeju Islanders have had a more expansive and less competitive view of education. In the context of Jeju being a maritime society, education became entwined with travel across the sea. Travel itself came to be seen as a form of education. Forty-eight per cent of Jeju islanders residing around Tokyo in the early 1990s responded in questionnaires and in life history interviews that they came to Japan “to study”, although most of them were not enrolled in schools or university; they were working. They felt that traveling outside Jeju and living in another society for a while was a form of education in itself (Koh 1996a, 50). This informal style of education, however, is not easily recognizable as education to peninsula Koreans.

During the twentieth century, especially with decolonization in the post World War II era, the nation-state model came to dominate imaginaries of political and cultural space. The structures and ideology of the nation-state system constrained Jeju Islanders’ regional practices. While transport developments meant travel was technically easier in the post war era, the imposition of territorial borders between the states of the region meant that Jeju Islanders’ travel was actually more restricted than it had been in either the Joseon or Japanese Imperial eras. China and North Korea became effectively off limits. Officially Japan had become a separate state for which a passport was required, and the South Korean government restricted overseas travel until the 1980s.

Patterns of living translocally in Japan as well as Jeju were so entrenched by the end of the colonial era, however, that Jeju Islanders continued sojourning to Japan, despite this being considered illegal by the governments of South Korea and Japan. Jeju Islanders owned properties and businesses in Japan and had family members there. The economic situation in Korea was dire until several years after the Korean War and the political situation on Jeju was unbearable for many, especially around the 4/3 Incident. In continuing to sojourn to Japan, Jeju Islanders were travelling as a way of life, as they had been doing for centuries. Now, however, these practices were criminalized and pushed underground. In the words of Tessa Morris-Suzuki, state responses to unsanctioned travel to Japan in the post war era rendered that travel “invisible” (Morris-Suzuki 2004).

Conclusion

Contemporary Jeju Islander travels to and from Japan contain vestiges of Todung Yagi travels in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries along the Korean, Shandong and Liaodong Peninsulas. Jeju society has for centuries existed in a spatial network across the maritime region of northeast Asia. This network has expanded and contracted in various directions as political situations in the region changed through the rise and fall of Joseon Korea, the Japanese Empire, and the Cold War. The modes of travel and types of work have changed, as has Jeju culture, especially during the twentieth century; still Jeju identities persist and Jeju culture flourishes distinct from other cultures.

Jeju in relation to Korea, China, Russia, Japan and Okinawa

In Confucian philosophies maritime regions were peripheral to the land-based centres of civilization, and were thus ignored and/or misunderstood. The modern era’s territorial system of nation-states made transborder ethnic identities such as kaijin are anomalous, and translocal practices of living across borders were criminalized and pushed out of sight. The significance of our failure to recognize these transborder identities and translocal practices is that we miss out on important historical lessons. The history of Jeju Island highlights some possibilities and dangers for small and marginalized ethnic groups. It demonstrates that contact with other peoples and cultures does not inevitably lead to homogenization, even for small politically subordinate societies. Jeju Islanders managed to retain much cultural autonomy. That autonomy was most threatened by state assimilation policies during the Cold War, and contemporary systems of education and media, but international norms have moved away from hard line anti-diversity nationalism for some decades, and the effects of this are being felt in the recent regeneration of local interest and pride in Jeju culture.

Being part of the Joseon administration, then the Japanese Empire and now the South Korean state has enabled Jeju to avoid invasion and domination by other powers. Administrative subordination has thus been in some senses expedient, and Jeju Islanders maintained some autonomy under that subordination. One way they did this was simply to carry on as they were without regard to the dominant administration wherever possible. Another way was through persistent and strategic lobbying through the dominant system. At times their activism was unable to protect them, such as during the early Meiji Japanese fishing incursions, and during the worst excesses of the South Korean military dictatorship. And these strategies were unable to protect Jeju Islanders from the material inequities associated with their subordinate status. But on the whole, the strategy of accepting formal subordination to a larger power, while actively maintaining some measure of autonomy, has met Jeju Islanders’ basic material needs, provided outlets for personal growth and cultural expression, and enabled Jeju society to thrive as a distinct system.

KOH Sunhui is a Research Associate, Institute for International Studies, University of Technology Sydney

[email protected]

Kate BARCLAY (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer, Institute for International Studies, University of Technology Sydney

[email protected]

This article was written for Japan Focus. Posted May 30, 2007.

Notes

[1] Some of the historical material in this paper was first published in Japanese (Koh 1998a; and 1998b). Judith Wakabayashi worked on initial translation into English. Koh Sunhui and Kate Barclay updated and reworked the material for an English language audience. Translations from Korean to Japanese are by Koh Sunhui. Translations from Japanese to English are by Judith Wakabayashi and Kate Barclay. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at a joint University of Technology Sydney and University of Guadalajara workshop on Globalization and Regionalization in January 2004 and the annual Centre for Research on Provincial China workshop held in the Hunter Valley, New South Wales, Australia in June 2004. Thanks to John McPhillips, David S.G. Goodman, Guo Yingjie, Peter Shapinsky and Jennifer Gaynor who provided helpful comments on earlier versions of the paper.

[2] For a brief discussion of histories focussing on this maritime region and references to longer treatments see Batten (2003, 39-40, 184-185). For discussion of Japanese adoptions of centre/periphery ideology see Part 2 ‘Centre and Periphery’ in Denoon (et. al. 1996), also Batten (2003, especially 28-48) and Kang (1997, 42). In addition to ideological influences, political developments on the mainland also affected perspectives on the maritime region. Ming Dynasty rulers had been politically engaged with the seafaring trade with other Asian countries, but from 1644 the Qing Dynasty rulers were more concerned with their territorial boundaries to the northeast and west, so they oriented government activities inland and left control of the sea trade to the merchants (Yanemoto 1999).

[3] Over the period covered by this paper there were various polities on the Korean peninsula so it is problematic to speak of ‘Korea’ as if the current idea of a Korean nation was salient in those times. Where appropriate specific terms such as Joseon Korea, the Korean peninsula and Cold War South Korea are used. For want of a better term ‘Koreanization’ is used in discussion about both Joseon Korea and South Korea; we hope the reader will gather from the context what we mean by ‘Korea’ in these cases.

[4] This myth of origin was recorded by Korean scholars in the early twentieth century. The fact that the scholars were from the peninsula, where inaccurate conceptions of the island abounded, and the fact that they had Japanese colonial education, could be expected to have influenced their representations of this myth. There have, however, been no significant refutations of the myth by Jeju Islanders, so we assume Jeju Islanders recognize the myth as theirs.

[5] Abalone was a symbolically important tribute commodity in Japan. It has been the most prestigious of offerings for Shinto deities, and even today is presented at the Ise Shrine. Abalone from Jeju (Tamla) was considered especially precious.

[6] Ama means women divers, kara means from the Korean peninsula.

[7] Representations by Japanese academics of cultural identity between the Japanese and neighbouring peoples served strategic colonial purposes in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In Taiwan and Okinawa these kinds of representations were explicitly used to justify colonial invasion and domination by Japan.

[8] The Ryukyu Kingdom also juggled relations with larger powers. It had informal trade relations with polities in what we now call China from at least the twelfth century, which were formalized into a vassal relationship under the Ming Dynasty, while concurrently the Japanese Satsuma domain extended political control over the Ryukyus from the late sixteenth century (Pearson 1996; Smits 1999).

[9] A Concise History of Jeju Island (Kim 1969) and The Early Years of Tamla (Kim 1918) are canons of Jeju Island history, but both scholars were Confucian-educated and were unable to critically uncover the Confucian ideology in the records to extrapolate from them a Jeju-centred version of history; rather they transmitted the biases embedded in the original records, including factual inaccuracies. According to Chun (1987) these biases in the historical record were transmitted in histories of Jeju published as late as the 1980s. These biases in histories of Jeju were not only ethnic, but also gendered and class based. Confucian-educated writers of records were men, usually of higher socioeconomic status, although schooling was not as restricted by social strata on Jeju as it was on the peninsula. Women and lower status men were mostly illiterate and had their own forms of historical traditions through story-telling and folk songs, which continue today to be vital forms of historical transmission for illiterate Jeju Islanders. More Jeju-focussed versions of history have emerged from studies of the language(s), folksongs and oral traditions of Jeju. See for example the annual Tamla Munhwa (Tamla Culture), produced by the Tamla Culture Research Institute of Jeju National University.

[10] The Jurchen people from the northern part of the Korean peninsula had seen Goryeo as their suzerain but came under the influence of the Wan-yen tribe of northern Manchuria who wanted to unify all Jurchen people, so from the late 10th to early 12th centuries the Jurchen fought with Goryeo along its northern border (Lee 1984, 126-128).

[11] For a compilation of all these figures see Koh (1998b).

[12] Funerary culture developed from a form of Buddhism, and as such was not strictly ‘Confucian’ but, in that there was a heavy emphasis on ancestor worship that bolstered Confucian visions of sociopolitical order based in the structure of the family, these religious practices may be seen as part of the cluster of practices that constituted Joseon Confucianism. Shamanism and Confucianism co-existed at funerals before being syncretised in Joseon Confucianism.

[13] A similar term kaimin has been used by Amino Yoshihiko (1994) to describe as aspect of Japanese society over history, which he feels has been as influential in shaping Japanese culture as wet-rice agriculture. The word min carries the connotation of ‘common people’, which in our view implies that maritime people were all of lower socioeconomic strata. Because this was not the case we use the broader term kaijin.

[14] Amino Yoshihiko (see 1994) has made this understanding widespread in Japanese history. Epeli Hau’ofa (1994) has proposed that the idea of oceans as connecting phenomena is appropriate for conceptualising Oceania.

[15] The records analysed by Takahashi contradict Masuda Ichiji who has stated that seasonal work on the Korean peninsula by the Jeju ama started only in 1895 (Masuda 1986, 79).

[16] The hospitality extended to survivors may also have been rooted in less directly pragmatic cultural values. According to Koh’s informants in the early twentieth century Jeju Islanders did not take food with them when they travelled around the island, because it was expected that when they needed food they simply asked for it from the nearest house, and Jeju houses always had extra food on hand for this. “Compassion” was cited amongst the “good things about Jeju Island” in a questionnaire conducted amongst Jeju islanders living in Japan in the twentieth century by Koh (1998) in the 1990s.

[17] The murdered Yang was a descendant of one of the founding families of Jeju Island and also a village official, and Pae-ryung-ri was a consanguineous village consisting of the Yang, Koh and Yi families. This was part of the reason his death galvanized such a strong reaction.

[18] Jeju Islanders made up a significant proportion of the Koreans “repatriated” to North Korea in the 1950s from Japan, having made the choice that socialist North Korea was the right place for them to live (Morris-Suzuki 2006).

[19] In fact, some of these long term Japanese residents and their descendants have not chosen Republic of Korea citizenship, for complicated reasons to do with the management of repatriation of ‘non-Japanese’ at the end of World War II, having lived outside Korea since the establishment of the Republic of Korea, as well as objections to a divided Korea and sympathies for the North through Chongryon, an organization that provided many practical and cultural supports for Jeju Islanders living in Japan (Morris-Suzuki 2004).

References

Amino Yoshihiko. 1994. Nihon Shakai Saiko: Kaimin to Retto Bunka (A Reconsideration of Japanese Society: Sea Folk and Archipelago Culture). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Aono Hisao. 1984. Aono Hisao Chosaku-shu (The Collected Writings of Aono Hisao). Tokyo: Kokon Shoin.

Batten, Bruce. 2003. To the Ends of Japan: Premodern Frontiers Boundaries and Interactions. United States of America: University of Hawai’i Press.

Choi Jae-sug. 1984. Jeju-do i Chinjok Chojik (Kinship Structures on Jeju Island). Seoul: Il Jisa.

Chun Kyung Soo. 1987. Sang Go Tamla Sa Hwe i Gi Bongu Fo Wa Un Dong Bang Huang (The Fundamental Structure and Orientation of Ancient Tamla Society). In Jeju Do Yongu (Studies on Jeju Island), Vol. 4. Jeju: Jeju Do Yongu Hwe.

Denoon, D. et al (eds). 1996. Multicultural Japan: Paleolithic to Postmodern, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eguchi Yasutaka. 1915 (May). Saishu-to Dekasegi Ama (Seasonal Women Divers from Jeju Island). In Chosen Gakuho (Research Publications on Korea). Seoul: Office of the Governor-General of Korea.

Fisheries Bureau, Agriculture and Commerce Division, Office of the Governor-General of Korea. 1910. Kankoku Suisan-shi (Korean Fisheries Journal), Vol. 1. Seoul: Printing Bureau of the Office of the Governor-General of Korea.

Fujinaga Takeshi. 1989. 1932 Nen Saish-to Ama no Tatakai (Jeju Women Divers Fight Against Japanese Colonial Occupation in 1932). In Chosen Minzoku Unodshi Kenkyu (Research into the History of Korean Ethnic Activism), Vol. 6.

Habara Yukichi. 1949. Nihon Kodai Gyogyo Keizai-shi (An Economic History of Ancient Japanese Fisheries). Tokyo: Kaizosha.

Hau’ofa, Epeli. 1994. Our Sea of Islands. Contemporary Pacific 61, 150-161.

Jeju 4/3 Research Institute. 2005. Outline. www.jeju43.org/outline/outline-3.asp (viewed 21 May 2007).

Jeong Ga Woon. 1988. Kaerimiru Yon-san Jiken no Kako to Genzai (Looking Back on the Past and Present of the 4/3 Incident). In Saishuto Yon-San Jiken to wa Nanika (What Was The 4/3 Incident on Jeju Island) edited by Saishu-to Yon-San Jiken 40 Shunen Tsuito Kinen Koenshu Kanko Iinkai (Publishing Committee for the 40th Anniversary Commemorative Collection of Papers on the Jeju Island 4/3 Incident), Tokyo: Shinkansha.

Kaji Nobuyuki. 1993. Jukyo to wa Nanika (What is Confucianism?). Tokyo: Chuko shinsho and Chuo Koronsha.

Kim Ok Hee. 1987. Jeju do Cheonjuu Kyoi Suyong Cheong ke Kwa Cheong (The Acceptance of Roman Catholicism on Jeju Island). Tamla Munhwa (Tamla Culture) No. 6. Jeju: Tamla Munhwa Yongu So (Tamla Culture Research Institute), Jeju National University.

Kim Tae Neung. 1969. Jeju-do Yaksa (A Concise History of Jeju Island). Jeju Island.

Kim Seok Ik. 1918. Tamla Kinyon (The Early Years of Tamla). Jeju Island.

Koh Chang Sug. 1993. Jeju do Keerok ge Natanan Jeju Pyoto ka in i Shilte (Survey of Shipwrecks on Jeju as Recorded in the Jeju Annals). Tamla Munhwa (Tamla Culture) No. 13. Jeju: Tamla Munhwa Yongu So (Tamla Culture Research Institute), Jeju National University.

Koh Sunhui. 1996a Zainichi Saishuto Shusshinsha no Seikatsu Katei: Kanto Chiho wo Chushin ni (The Lives of Jeju Islanders Residing in Japan: Focus on the Kanto Region). Tokyo: Shinkansha.

—- 1996b Jeju Islanders Living in Japan during the Twentieth Century: Life Histories and Consciousness. Doctoral Thesis, Department of Sociology, Chuo University, Tokyo. Includes volumes: Records of Life Histories Vol.1-3; Records about Illegal Immigration; Records of Interviews with Jeju Islanders Living on “Skid Row” (yoseba); Records of Jeju Islander’s Village Society Association.

—- 1998a. Saishutojin no Kokka/Kokumin Ishiki wo Megutte (On Jeju Islanders’ Consciousness of State and Nationality). In Horumon Bunka, Vol. 8. Tokyo: Shinkansha.