The Bataan Death March and the 66-Year Struggle for Justice

Kinue TOKUDOME

April 9, 2008 marks the 66th anniversary of the fall of Bataan which resulted in the largest surrender by the United States Army in its history. Over 77,000 American and Filipino troops were to become victims of one of the most brutal episodes in the Pacific War—the Bataan Death March.

The March: Beginning of the Ordeal

In 1941, the Filipino people were already promised independence from the United States, which had seized the islands nation from Spain during the Spanish-American War. But with the Japanese expansion to Southeast Asia beginning to pose a threat, Gen. Douglas MacArthur was recalled to active duty to prepare for a possible Japanese attack. When the attack did come, MacArthur’s initial plan to halt the Japanese invasion at the beaches failed. As a result, tens of thousands of US troops who retreated to Bataan, the peninsula in central Luzon, did not have enough food or medicine to sustain their fight. MacArthur, who moved his headquarters from Manila to the island of Corregidor across Bataan, continued to send orders: never surrender.

Then on March 12, 1942, he escaped to Australia. This left the men in Bataan to keep fighting until their ammunition, food, and medicine ran out, upsetting the Japanese timetable for victory and giving the United States precious time to recover from the Pearl Harbor attack. By the time more than 11,000 American and 66,000 Filipino soldiers surrendered on April 9, 1942, they were starving and most were stricken with malaria, beriberi or dysentery. “Thousands of troops and hundreds of planes” that MacArthur had assured them were on the way to rescue them never arrived.

Bataan Death March survivor Lester Tenney of the 192nd Tank Battalion wrote years later:

“In every battle there comes a time when one group of warriors must be sacrificed for the benefit of the whole…,” declared President Franklin D. Roosevelt during one of his fireside radio chats in March 1942. The battle he spoke of was the battle of the Philippines, and the warriors were those fighting American men and women on Bataan and Corregidor…. [1]

Then began the March. The Japanese military had no plan to systematically torture and murder the POWs. But it sought to move American and Filipino soldiers out of Bataan quickly so that it could immediately launch attacks on Corregidor. The Japanese soldiers also despised POWs who chose to surrender instead of fighting to death.

Bataan Death March survivor Glenn Frazier testified in the recently aired PBS documentary The War, “If we had known what was ahead of us at the beginning of the Bataan Death March, I would have taken death.” He described what happened next:

And they immediately started beating guys if they didn’t stand right or if they were sitting down. We didn’t know where we were going… And all our possessions were taken away from us. Some of them had rings that they just cut the fingers off, and take the rings. They poured the water out of my canteen to be sure that I didn’t have any, any water. I saw them buried alive. When a guy was bayoneted or shot, laying in the road and the convoys were coming along, I saw trucks that would just go out of their way to run over the guy in the middle of the road. And when by the time you have fifteen or twenty trucks run over you, look like a smashed tomato or something. And I saw people that had their throats cut because they would take their bayonets and stick it out through the corner of the truck at night and it would just be high enough to cut their throats. And beating with a rifle butt until there just was no more life in them.

Glenn Frazier’s testimony.

Glenn Frazier in PBS documentary “The War”

Glenn Frazier in PBS documentary “The War”

Harold Poole of Army Air Corps also remembered:

Some of the guys would just faint, they were that weak. This guy was no more than five feet away. He was lying facedown. The guard poked him and he didn’t move fast enough, so he got the bayonet right through his back….

I could hardly believe what I saw….

I wanted to jump that guard and grab his rifle and wrap it around his neck, and I could have in those days. I was still in pretty good shape and those guys were a lot smaller than us. I could have jumped up and wrapped that gun around his neck and he’d never have known what hit him. But you know, there was another guard behind him and he would have shot me and that would have been the end of me, see. [2]

Louis Read of the 31st Infantry Regiment witnessed a killing of his fellow POW:

One incident at Lubao shook me up. I spent all my time during the day standing in line for the one water hydrant to fill my canteen. I was almost up to the hydrant when a Japanese officer came up, looked us over, and selected a rather tall, good-looking soldier, who was just in front of me, out of the line. The officer, for no apparent reason, turned over this man to a group of soldiers who took him across the road, tied to a tree and used him for bayonet practice. From my place in line, I saw the whole thing. After he was dead they took his body and threw it into a large bamboo clump. Then, just as I got to the hydrant, the Japanese soldiers pushed me aside and washed the blood off of their bayonets. [3]

After trudging for four to seven days and reaching to the town of San Fernando, Filipino and American POWs were herded into boxcars. They were packed so tight that they could hardly move. Doors were shut and the temperature inside the boxcars quickly rose. Men gasped for air and some died while standing. Those who survived four-hour ride in the boxcar prison had to walk another few miles from Capas to reach their destination, Camp O’Donnell.

No one knows exactly how many died on the Bataan Death March, but even by the most conservative estimate approximately 6,000 Filipinos and 650 Americans lost their lives.

Carrying the dead to gravesites, April, 1942

The death toll rose even higher after they arrived at Camp O’Donnell. Captain John Olson was Adjutant of the American Group at Camp O’Donnell and kept records on the deaths that took place there. He later wrote:

Camp O’Donnell’s appearance in the endless stream of History was brief, but dramatic. During its less than nine months as a concentration area, it saw some 1,565 American and over 26,000 Filipino, all in the prime of life, perish ignominiously and needlessly. Because of the callousness and inefficiency of an enemy who relentlessly applied an atavistic code of conduct to dealing with helpless individuals, they were not treated according to the codes subscribed to by most of the nations of the Twentieth Century. Though what happened to the Americans was reprehensible, the studied extermination of the Filipinos, whom the Japanese had ostensibly come to free from the “Tyrannical Oppression” of the Imperial Americans, is utterly inexplicable. [4]

Hellships

The ordeal continued for American POWs who survived the Bataan Death March and Camp O’Donnell. Most of them, together with the POWs who were captured after the fall of Corregidor, were eventually sent to Japan to become forced laborers. The ships whose holds POWs were crammed into were aptly called “Hellships.”

The late Col. Melvin Rosen who survived the Bataan Death March described what it was like on a Hellship:

Over 600 men crowded in a metal hold with no ventilation other than one hatch. There were no sanitary facilities. We did use some empty food buckets, but they were soon overflowing…By nightfall the hold was pitch black, and men went mad from lack of water and food. They were completely crazed and were drinking urine. Although I did not personally see any, I believe there were murders and drinking of blood. The conditions in the hold and of the people were beyond belief….

The daily death rate on the Brazil Maru escalated from about 20 to 40. Now we were sailing in the East China Sea with snow coming in our open hatch. Men froze to death, died of starvation, died of thirst, and died of a myriad of diseases. Again there were no sanitary facilities, and so the hold was ankle deep in feces, urine, and vomit. [5]

Although many died from diseases during the voyages, the majority of deaths on Hellships occurred when American submarines and bombers attacked and sank these unmarked ships. Thousands of POWs perished. One Hellship, the Arisan Maru, lost all but eight of its entire human cargo of 1,800 American POWs when it was sunk by a US submarine.

Forced Labor in Japan

POWs who survived Hellship voyages were then forced to work in mines, factories and docks owned by Japanese companies such as Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Nippon Steel. Beating and other abuse continued while food and medicine were never adequate.

Bataan Death March survivor James Murphy of Army Air Corps described how 500 American POWs were brutally treated at Mitsubishi Osarizawa copper mine in northern Japan.

We were subjected to perilous working conditions and strenuous physical labor beyond belief. The guards and officials were trained to be barbarous and savage in their day-to-day exploitation and control of us. The egregious act against us by the Japanese included beatings with clubs, rifles, shovels, picks and other objects. We were struck with fists and kicked with booted feet causing gashes, contusions and ulcers.

Even though our conditions of malnutrition, starvation, disease, and illnesses were plainly evident, the Japanese did nothing to remedy these. We were not fed; our illnesses and diseases were not treated; but they continued to work us harder and harder to increase copper mine production. [6]

Lester Tenney, who was forced to work at Mitsui coalmine in Kyushu, remembered that brutality of Japanese guards increased as American bombings of Japanese cities intensified in the winter of 1944.

I was hit with the swinging chain three times, all within a month or two and always for the same reason: the Americans had bombed one of the Japanese cities and killed some of the residents. I had expected some form of retaliation. When I was hit with the chain the first time, it fell across my lower back. I felt as if my back had been broken in two. [7]

By the end of the war, 1,115 American POWs died in Japan from abuse, diseases, and even executions.

After the War

The US government and its military leaders first learned about the Bataan Death March and the atrocities inflicted on American soldiers in the summer of 1943 from one of the officers who had survived the Bataan Death March and later escaped from the prison camp in Mindanao. But the media were not allowed to publicize it until January of 1944. Once they learned about it, the American public was shocked and outraged by the Japanese brutality. The outrage was shown in President Truman’s address after the dropping of the Atomic bombs:

We have used it against those who attacked us without warning at Pearl Harbor, against those who have starved and beaten and executed American prisoners of war, against those who have abandoned all pretense of obeying international laws of warfare. [8]

General Masaharu Homma, the commanding general of the Japanese Army in the Philippines during the Bataan Death March, was tried and executed on April 3, 1946. Hundreds of prison guards who abused POWs would meet the same fate.

But in a mere six years, the outrage was to be replaced by geopolitics prevailing in the Far East. In 1951, the US government signed the Peace Treaty with Japan, which included a provision waiving claims of former POWs against Japan. The United States needed Japan within its camp against the Communist Soviet bloc and chose not to seek compensation from Japan. Former POWs of the Japanese felt that they were sacrificed by their own government again.

During those days, however, former POWs were busy rebuilding their lives while struggling to come to terms with their wartime sufferings.

Bataan Death March survivor Carlos Montoya of the 200th Coast Artillery described his post-war struggle:

For the first five years after the war, I drank heavily. I was still very angry. I drank to get my memory out of me. One time my wife was pregnant and I took her to our doctor whose office was on the third floor of a bank building. We were waiting for the elevator in the lobby on the first floor. The elevator door opened and out came a Japanese person. I jumped on him and got him by the throat. I put him on the floor and was kicking him and hitting him. People around us didn’t know what was happening and called the police. The police came and asked what was wrong. So my wife told him that I was a prisoner of war in Japan. I was going to kill that Japanese. When the police found out what the fight was about he said to the poor Japanese to get going. So I had to watch myself that I wouldn’t see Japanese….

In 1972, I even went back to Niigata with the full intention of killing the guard who had tortured me while I was a POW. I carried my pistol. Looking back now, I was still mentally sick at that time. I had a lot of anger. [9]

Each survivor had to find his own way to deal with the painful memory of being a POW of the Japanese. Not many people understood “post traumatic stress disorder” in those days.

Robert Brown of Army Air Corps was only 17 years old when he walked the Bataan Death March. He weighed 82 pounds when he was sent to a POW camp in Mukden, Manchuria. He was liberated by Soviet forces in August 1945. When he came home, he did not know how to readjust to normal life:

I came home, but I was still in jail… I couldn’t sleep… I couldn’t converse with anybody. I spoke some Japanese and knew some Chinese cuss words. But I couldn’t talk to anyone…There were no jobs. I was uneducated, for all purposes. I knew I could survive in a prisoner-of-war camp, but what else could I do? The only thing I could do was to drink.

One time, I was sleeping and was having flashbacks. My mother came in to shake me and wake me up. I came out of the bed and held her by the throat. I woke up and said, “What in the hell am I doing!” I told her, “Mother, don’t ever come in and touch me when I am sleeping because I don’t know what I am going to do.” [10]

Bataan Death March survivor Abie Abraham of the 31st Infantry decided to stay in the Philippines after General McArthur personally ordered him to exhume bodies of American soldiers who died on the Bataan Death March. He discovered hundreds of remains along the route of the Bataan Death March, some of them belonged to his friends:

I went for the body of my old friend, Luther Everson, whom I had known well before the war. I recalled that as we were wavering and staggering out of Balanga, we crossed a bridge and I saw Luther fall. He tried to get up and fell again. I saw a Japanese soldier club him to death.

From under a bamboo thicket we disinterred his grave. The diggers handed me a skull. I shuddered and showed them the deep crack left by the Japanese club. All eyes stared as though awe-stricken.

“Sergeant Everson and I used to drink at the NCO Club before the war,” I told them. “Now I’m holding his skull! A good and kind human being killed because he was sick, hungry, and thirsty, and tired….” [11]

Very few were lucky to find a medium with which to express their POW experience. Ben Steele of Army Air Corps is a survivor of the Bataan Death March and nearly a year of forced labor in a Japanese coalmine. But he is most famous for his drawings and paintings depicting his experiences as a POW of the Japanese. He began to draw while in a prison camp in the Philippines, but all but two original drawings were lost. He would recreate many of those drawings after he came back home. Eventually, his artwork became one of the most comprehensive and expressively powerful visual records of the prisoner-of-war experience under the Japanese.

Ben Steele “The Water Line” [12]

Ben Steele “The Water Line” [12]

Seeking an Honorable Closure

It was not until 54 years after their liberation that survivors of the Bataan Death March and other former POWs of the Japanese filed lawsuits against the Japanese companies that enslaved them. Such lawsuits became possible under a California law enacted in 1999. The applicable portion of the law reads:

Any Second World War slave labor victim…may bring an action to recover compensation for labor performed as a Second World War slave labor victim or Second World War forced labor victim from any entity or successor in interest thereof, for whom that labor was performed, either directly or through a subsidiary or affiliate. [13]

Lester Tenney was the first plaintiff to file a lawsuit against Mitsui. Soon, more than thirty lawsuits were filed against almost sixty Japanese companies. The governments of both the United States and Japan sided with the Japanese defendant companies and strongly urged the court to dismiss the cases based on the Peace Treaty.

On September 25, 2001, three former Ambassadors to Japan, Walter Mondale, Thomas Foley, and Michael Armacost, wrote an opinion piece for the Washington Post. Arguing against bills pending in Congress to support POW lawsuits, they wrote that such measures, “would undermine our relations with Japan, a key ally. It would have serious, and negative, effects on our national security….Why would Congress consider passing a law that could abrogate a treaty [the San Francisco Peace Treaty] so fundamental to our security at a time the president and his administration are trying so hard to forge a coalition to combat terrorism?”

After more than four years of pre-trial maneuverings, POW forced labor lawsuits were all dismissed. The court found the California law to be unconstitutional because it would interfere with the federal law (treaty). But one could not blame the POWs for filling these lawsuits. They simply tried to exercise the right they had under the California law. The author of this law, former California Senator Tom Hayden, wrote to this author when she asked him if he was aware that his law might be in conflict with the Peace Treaty:

We consulted lawyers and looked at the Treaty. There is nothing about the Treaty that can abrogate the right of an individual to seek redress for slavery or forced labor, nor anything barring a state from protecting its citizens in such case. [14]

Yet his law was found unconstitutional and placed aging former POWs on an emotional rollercoaster for four years.

That their own government tried to block their day in court at every step of the way hurt former POWs more than anything else. They could imagine that the Bush administration would not want to see anything that upset the valuable ally, Japan, in its war against terror and later its war in Iraq. Still, knowing that the US government could have facilitated a settlement, as it did for the German slave labor victims, they again felt that they were sacrificed. The poem they used to recite in Bataan evoked renewed emotion among the Death March survivors:

The Battling Bastards of Bataan

No mamas, no papas, no Uncle Sam,

No aunts, No uncles, no cousins, no nieces

No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces,

And nobody gives a damn.

Because the goal for the lawsuits was to bring an honorable closure to their wartime sufferings, former POWs did not consider the dismissal of their lawsuits to be the end of their fight. They hoped that the legally exonerated Japanese companies and the Japanese government would come forward, acknowledge the POW abuse during WWII, and offer a sincere apology without concerns about compensation. That never happened.

In April of 2007, about 70 members of American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor (ADBC), the national organization of former POWs of the Japanese, gathered in the nation’s capital to attend their annual convention. Most of them were in their late 80s and 90s and knew that this would be the last time that such a large number of former POWs of the Japanese would be in Washington DC together.

They passed a resolution that sought an official apology from the Japanese government. Lester Tenney, the Vice Commander of ADBC, had drafted the resolution and planned to personally deliver it to the Japanese Embassy. Although he had asked the Embassy weeks in advance for a brief meeting with Ambassador Kato Ryozo or anyone who would receive the resolution, his request was ignored. On the day Tenney and the longtime leader of ADBC, Edward Jackfert, intended to visit the Embassy, they called the Embassy asking if they could deliver their resolution. They were told that no one would be available to meet them.

A few weeks later, President Bush accepted Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s apology for the “Comfort Women” issue when they met in Washington DC.

Children’s Effort to Honor POW Fathers

Although there has been very little governmental effort in the United States or Japan to remember and honor those who walked the Bataan Death March, some Americans are finally realizing that these special veterans deserve much better than they have been treated so far. The most dedicated among them are children of POWs.

In January of 2006, the “Hellships Memorial” was dedicated in Subic Bay in the Philippines. The late Navy Captain Duane Heisinger, whose father died on a Hellship, spearheaded the effort to build this memorial. The inscription he wrote ends with the following sentences:

This memorial will offer a place of quiet reflection to future generations who must discover the extraordinary sacrifice of these heroes, not only that they may draw inspiration from their example but also to reaffirm the enduring hope of a world set free from war.

The Hellships Memorial will forever speak of this hope, serving as an anchor holding fast against the slow currents of complacency and forgotten loss.

This memorial was established and is supported by former prisoners of war of the Japanese, family and friends of those who died, and those who survived the endless nightmare of being a POW.

Hellships Memorial (Subic Bay) Inscription

Hellships Memorial (Subic Bay) Inscription

Federico Baldassarre, whose father survived the Bataan Death March, has been working with members of the Filipino Bataan veteran’s organization and descendants of marchers to preserve one of the boxcars that carried POWs in the last part of the Death March. Their tireless efforts came to fruition in October of 2007 when they successfully placed the boxcar in the Capas National Shrine, which houses both the American and Filipino Memorials for those died in Camp O’Donnell.

Boxcar in which Bataan Death Marchers were carried to Camp O’Donnell

Boxcar in which Bataan Death Marchers were carried to Camp O’Donnell

Baldassarre, who has been helping “Battling Bastards of Bataan” for many years, wrote to this author:

For those of us whose father, grandfather, uncle or great uncle rode the rail from San Fernando to Capas in April, 1942, the boxcar is a priceless relic, a physical manifestation of their horrific journey from Bataan to Camp O’Donnell.

We can only imagine how it must have felt after marching for four to five days on Bataan’s East Road, while being purposely dehydrated, starved, beaten, watching those around you being shot, bayoneted, decapitated, buried alive at the rest stops, having the intense tropical sun and it’s relentless heat anesthetize their senses, and experiencing the macabre, and taunting, cruelty of their guards, to be suddenly thrust into the boxcars, jammed so tightly together that those who died had no room to fall.

It now sits amongst the spirits of its former passengers. There it sits for all of us to visit.

Retired Army Colonel Gerald Schurtz’s father survived the Bataan Death March, but died on a Hellship. Today, Col. Schurtz is one of the organizers of the Bataan Memorial Death March held annually at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

The event that was started by the Army ROTC Department at New Mexico State University in 1989 with just 100 participants has grown into an enormously popular event. On March 30, 2008, more than 4,400 participated in the 19th annual Bataan Memorial Death March. They ran or walked either the full 26.2 miles or the honorary course of15.2 miles to honor those brave heroes who fought in the defense of the Philippines during WWII.

Each year, survivors of the Bataan Death March are invited as special guests. One of the participants described his feeling upon meeting them:

Meeting the original March’s survivors was a very humbling experience. They truly are awe-inspiring men. Standing before them, I really did not know how to thank them for their sacrifices, and for their courage in facing a merciless enemy. While I was shaking the hands of the survivors at the start/finish line, one of them looked at me and simply said “Thank You for being here”. I have no words to express the emotion I felt at that moment. I will remember that for the rest of my life. [15]

Death March survivor Robert Brown shakes hands with participants

Death March survivor Robert Brown shakes hands with participants

Among the marchers in recent years were “wounded warriors” who lost their limbs in the war in Afghanistan or Iraq and parents of the soldiers who died fighting there. They paid tribute to the original

Bataan Marchers by walking with their artificial legs or wearing a shirt with a picture of their fallen son printed on it.

Col. Schurtz hopes to have participants from Japan in the future.

Bataan Death March on TV and Screen

In the fall of 2007, PBS aired a documentary on World War II, “The War,” produced by Ken Burns. It was reported that 37.8 million people watched it during the initial broadcast premiere. [16]

The episodes of American military POWs and civilian POWs of the Japanese were prominently featured in this documentary. Bataan Death March survivor Glenn Frazier said that he was at the right place at the right moment to be selected to appear in the documentary. When he spoke about his POW experience and his post war struggle with hatred towards the Japanese, Ken Burns said that was what he wanted him to say on the camera. In the last episode of this 15-hour documentary, Frazier recounted his struggle with the hatred that had consumed him nearly 30 years after the war.

When I left Japan I had all kinds of hatred for these people. And it was so imbedded into me, I felt like I was justified to have hate… But I had to get rid of that hate, and it took me 29 years to realize that that’s why my health was going bad. That’s why my whole life was miserable, because of the hate…

And they, and my preacher ask, the preacher I was going to asked me to, I had to give, forgive myself and had to forgive them. I said, ‘Forgive the Japanese? You’re kidding. How in the world can I do that?’ I said, ‘They’ve never apologized to me. Or anybody else. They never made any effort to, to smooth over what they did to us. So why shouldn’t I hate ’em. I hafta.’ He said, ‘Well, you not gonna make it that way.’ …

(Frazier testimony here.)

Encouraged by the general population’s renewed interest in the Bataan Death March and the success of a movie like “Letters from Iwo Jima,” Hollywood is now making a film on the Bataan Death March. The story will focus on the trial of General Homma. The promotional website shows a synopsis of the film:

1945 Tokyo/Philippines. Four young military lawyers receive the least desirable assignment in the entire postwar occupation of Japan from Supreme Commander Douglas MacArthur – they are to represent a Japanese General who has been accused of being responsible for the notorious Bataan Death March.

At first they do their best to evade their new career-destroying assignment. Then they begin to discover that General Homma, known as the “Beast of Bataan,” is a good and honorable man who was not, in fact, involved with the crimes for which he was accused. But MacArthur bears a secret grudge against Homma, who was the only Japanese officer to ever defeat him in battle.The young American military lawyers endeavor to save Homma from his obvious fate, fighting not only their own commanding officers but also Homma himself, who knows he is destined to die.

This is a story in which villains turn out to be heroes, heroes turn out to be villains, and a group of young soldiers, along with an imprisoned alleged war criminal, provide a lesson in courage. [17]

The producer of this film, Jonathan Sanger, wrote to this author:

There is no attempt, in the film, to underplay the atrocities committed on the Bataan Death March, nor to dishonor, in any way, the memories of Bataan survivors. The movie clearly establishes events that occurred as told by participants in the trial of General Masaharu Homma. Issues of command responsibility are treated in what I hope will be an evenhanded way.

This is a story of war at its worst and we hope it will be viewed by both Americans and Japanese in that light. [18]

Sixty-Six Years Later

“American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor” has been holding an annual convention since 1946. Young ex-POWs in the immediate post war years are now in their late 80s and 90s and their numbers are dwindling. They have decided that they will disband their organization in the spring of 2009. Lester Tenney will be sworn in as their last National Commander in May, 2008. He is determined to obtaining an apology from Japan before the 63-year-old organization of former POWs of the Japanese ceases to exist.

Tenney has been invited by the Chief of Operations of the USS Arizona Memorial to sit on a panel on Memorial Day to discuss and review events of the war in the South Pacific. He decided to extend his trip to Japan to make one more, and likely his final, effort to obtain an apology from the Japanese government and those companies that enslaved American POWs. In his letter to Prime Minister Fukuda Yasuo he wrote:

Mr. Prime Minister, it is our desire to resolve the POW issue. Doing so will no doubt be in the best interest of we former POWs and your honorable country, and will at last bring closure to we old soldiers of this long-ago tragic event. We survivors are entering our twilight years, and our organization will soon be forced to disband due to the demise of its remaining members. When that time comes, there will be no survivors left to accept an apology.

Col. Melvin Rosen passed away on August 1, 2007, at the age of 89 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Other Bataan survivors are busy.

Tenney (88) recently received an offer from a well known Chinese reporter and major Chinese publisher to have his story of WWII and his life as a POW of the Japanese translated and published in China. His book, “My Hitch in Hell” would be retitled to “My Time in Hell.” It would be the first first-person account, to be published in China of the horror of the Bataan Death March and the three and a half years spent as a POW of the Japanese.

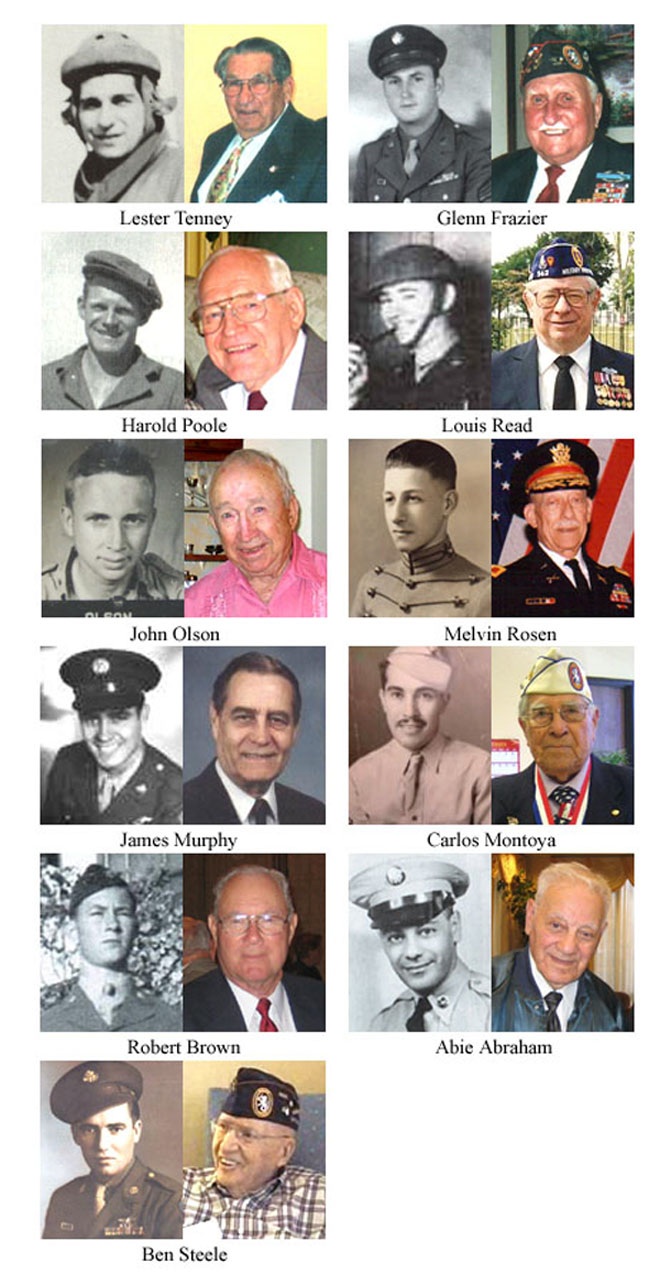

Glenn Frazier (84) has just published a book, “Hell’s Guest,” and is giving speeches across the country. Harold Poole (88) will be featured in a documentary now being made by James Parkinson whose book, “Soldier Slaves,” chronicled Poole’s POW experience and his lawsuit. Louis Read (87) is active in the American EX-Prisoners of War organization and in the local Purple Heart Chapter. John Olson (90) is a historian for the Philippine Scouts Heritage Society. James Murphy (87) recently finished writing his POW memoir with his wife Nancy. Carlos Montoya (92)’s biography, “Carlos,” was published by his nephew J. L. Kunkle last year. Robert Brown (83) recently went back to Mukden (now Shenyang), China where the Chinese government restored the Japanese POW camp and turned it into a museum. He was also awarded a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star just recently. Abie Abraham (94) still volunteers at VA hospital. Ben Steele (90) just made a presentation on his POW artwork during the Bataan Memorial Death March in New Mexico.

Acknowledgements

The Bataan Death March survivors and the children of Bataan marchers, whose stories I have introduced in this essay, have been helping me understand the history of American POWs of the Japanese for many years. I thank them all for sharing their stories, their feelings and their hope for a lasting friendship.

Bataan Death March survivors then and now

Kinue Tokudome is a Japanese writer. She has contributed articles to Japan Focus on the Japanese military comfort women and on US POWs.

She maintains the bilingual website, “US-Japan Dialogue on POWs.”

She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on April 8, 2006.

Notes

[1] Lester Tenney, My Hitch in Hell: The Bataan Death March (Washington, 1995) XV.

[2] James W. Parkinson and Lee Benson, Soldier Slaves: Abandoned by the White House, Courts, and Congress (Annapolis, MD, 2006), p. 68.

[3] Interview by the author, 2004.

[4] John E. Olson, O’Donnell: Andersonville of the Pacific (1985), p. 177.

[5] Interview by the author, 2002.

[6] Interview by the author, 2004.

[7] Tenney, p. 163.

[8] President Truman’s radio address on August 9, 1945.

[9] Interview by the author, 2005.

[10] Donald Knox, Death March: The Survivors of Bataan (New York, 1981), p. 463, and interview by the author.

[11] Abie Abraham, Ghost of Bataan Speaks (PA, 1971), p. 163.

[12] Ben Steele, Prisoners of War (Billings, MT, 1986), Cover Illustration.

[13] California Code of Civil Procedure Section 354.6

[14] Email from Tom Hayden to the author, Nov. 27, 2003

[15] From the official website of BMDM.

[16] From PBS website.

[17] See website.

[18] Email from Jonathan Sanger to the author, March 14,2008.