Kate Barclay

Summary

This paper explores conflicting representations of Japanese fishing practices in a joint venture company in the Pacific. Western and Islander representations frequently included suspicions that Japanese management was cheating their local partner and engaging in illegal and ecologically destructive fishing practices. In contrast, Japanese self-identified as as socially and ecologically responsible in contrast to the callous disregard for employment security and destructive industrial fishing methods used by Americans. Analysis of these different perspectives shows underlying conflict about whose development assistance is best, with Islander perspectives demonstrating postcolonial reactions to their continued subordination in the world system. [1]

Introduction

Research on a joint venture tuna fishing and processing enterprise based in the Solomon Islands from 1971 to 2000, Solomon Taiyo Ltd., provides a means to investigate clashing conceptions of identity and modernity. The analysis is based on interviews, news media and government documents. Japanese self-representations are juxtaposed against representations by Westerners and Islanders. Both Western and Islander representation of the Japanese-owned firm Solomon Taiyo frequently included suspicions that management was cheating its local partner, the Solomon Islands government and that the company was engaged in illegal and ecologically destructive Japanese/Asian fishing practices. Representations of Solomon Taiyo to some extent varied according to whether the commentator was of Western descent or Solomon Islander, reflecting different relations with Japan, but in general depicted the Japanese as bringing a ‘bad’ kind of modernity to the Islands. By contrast, Japanese representations of business and fishing practices contrasted their own socially and ecologically responsible behavior with Westerners’ callous disregard for employment security and destructive industrial fishing methods. Japanese involvement in Solomon Taiyo was self-identified as a charitable mission for the economic and social development of the Solomon Islands. Japanese managers saw themselves as bringing a ‘good’ modernity to Solomon Islands.

Japanese and Western modernities are similar in that they are both capitalist, although there are also some culturally and historically contingent specificities, such as shorter/longer time frames and different attitudes towards relationships of obligation. This paper does not address the concrete nature of Japanese and Western modernities, or which might be best for Solomon Islands (probably neither, Solomon Islanders’ own modernity would likely be best). Neither does it assess how beneficial the company was for Solomon Islands in terms of material economic development, I have discussed that elsewhere (Barclay 2000; 2005; forthcoming). The central concern here is the subjective aspects of the social interactions of the company; specifically to reveal the politics informing narratives that view development projects as good or bad because of the ethnicity of the people involved. Narratives that portray Japanese fisheries as good or bad are influenced by the subjective positions of the narrators, a point that is useful to bear in mind when considering contemporary public debates about over-fishing and whaling.

The concepts of identity and modernity frame this discussion. Scholars such as Michael Billig have convincingly argued that nation is the most important communal identity in today’s world (Billig 1995) [2]. National identity is in turn greatly influenced by ideas about modernity. Marshall Berman has shown that the aesthetic and literary movements most usually associated with modernism may be grouped with more materialist movements such as Marxism and modernization theory as an overall worldview ordered by a teleological striving for modernity (Berman 1982). Marianne Torgovnick’s work on the appreciation of primitive art demonstrates that modernity requires as its flipside the creation of a primitive against which it can be defined (1990), in much the same way as Europe required the Orient in Edward Said’s seminal work Orientalism (1978). For their part critical development theorists have asserted that developmentalist discourses, visible in preoccupations with ‘progress’ and ‘development’—or their lack—in representations of peoples, have acted to denigrate peoples identified as underdeveloped (Manzo 1991; Sachs 1997; Escobar 1997; Hanlon 1998). Taken together these apparently disparate pieces of social theory build the argument that ideas about modernity have long been influencing communal identities, especially nations [3]. The conflicting perspectives on Japanese identity in relation to modernization and capitalist development in fisheries discussed in this paper serve to underline the contested nature of modernity, and of histories of modernization.

The identities discussed in this paper are sometimes about race, sometimes nation, and occasionally about class. Rather than pinning it down to only ‘race’ or ‘nation’ or ‘ethnicity’, I prefer to discuss using the umbrella term ‘identity’. The terms ‘Japanese’, ‘Asians’ ‘Solomon Islanders’ and ‘the West’ used in this paper are inherently problematic, but are the most expedient to enable coherent discussion. ‘European-descent English speaking people’ were usually referred to by Solomon Islanders as ‘European’ (although it included mostly Australians and New Zealanders), or local terms such as arai kwaio or tie vaka. In this paper ‘Westerner’ will be used, except where the people under discussion are more specifically identified with a particular place (such as the US). ‘Japanese’ in the context of Solomon Taiyo sits uncomfortably over a split between mainland Japanese managers and Okinawan fishermen, and uneasily under the umbrella term ‘Asian’. For the purposes of this paper, however, it is possible to speak of ‘the Japanese’ to the extent that they were spoken of as such by the participants in the research.

It is also the case that, in a world of cultural flows and diffusions, ideas are not discreet units belonging exclusively to any one group, so it is problematic to attribute ethnic provenance to representations, such as calling them Western or Japanese, as I do here. Japanese categorizations of peoples have been influenced by Western categorizations of peoples, especially in terms of ‘nation’ and modernist understandings of ‘civilization’ (Dikötter 1997). Likewise Solomon Islander categorizations of peoples have long been influenced by English language representations, both in the colonial period and after, when Australians and New Zealanders have occupied prominent positions in Solomon Islands society and where English is one of the important languages. Global English language representations of peoples are thus part of the worldviews of all the players in this research. It is not the case, however, that representations from all groups were the same; there were discernable differences between types of representations, and it is on this basis that (slippery) attributions of certain representations as belonging to particular ethnic groups are used in this paper.

Solomon Taiyo Ltd

Solomon Islands is a double chain of islands stretching into the western Pacific south east of Papua New Guinea and north east of Australia, with a current population of around 400,000. These islands were annexed by Britain in the late nineteenth century. Solomon Islands first became significant to Japan in World War II when it was a key battlefield in the Pacific War. Of the nearly 400,000 Japanese (and conscripted Taiwanese and Koreans) who went to Melanesia during World War II, over sixty per cent died there, mostly from starvation and sickness (Nelson 1982). Over 20,000 Japanese troops died on Guadalcanal.

Japanese occupation of Solomon Islands was not like the long-term colonial situation in other former German territories in the Pacific. Japanese forces only reached Solomon Islands in 1943, at the furthest stretch of Empire, managing to maintain military occupation in some parts of the islands before being turned back by US forces in 1944. Oral histories of the war years indicate that Solomon Islanders vacated the parts occupied by the Japanese, so there was very limited contact (White and Laracy 1988). Some Solomon Islander men were employed by US forces, but none seemed to have worked in this way for the Japanese. Most Solomon Islanders thus avoided being caught up in the fighting, although the war years must have been difficult for those displaced from areas where fighting was occurring.

Although the Japanese ousted the British colonizers, Solomon Islanders did not identify the Japanese as liberators, instead most saw US forces as their saviors and identified the Japanese as the enemy during the war and for some decades after. Hungry Japanese soldiers stole food from villagers. Apparently Japanese soldiers defecated on the desks of colonial District Officers, which may or may not have been seen as a bad thing by Solomon Islanders, but they also defecated on sacred places, which was certainly taken as an insult (Fifi’i 1989, 45-47). Although many saw the Japanese as the enemy, a collection of Pacific Islander oral histories of World War II showed that there were those who ‘approached both sides with wariness, pragmatism, and humanity’ (White and Laracy 1988, 3). Some Solomon Islanders felt the Japanese were less racist towards them than were the British colonizers (BSIP 1972a, 80). But on the whole it is fair to say that the war background was a negative starting point for interactions with the Japanese in Solomon Taiyo. According to former fisherman Hirara, when his fishing boat first ventured into Solomon Islands fishing grounds in the early 1970s, many villagers ran screaming into their houses, or threw rocks, because they associated Japanese ships with war [4].

By 1970 the British colonial administration was preparing Solomon Islands for Independence (1978). The administration deemed that there was not enough of a capitalist economic basis for independent statehood so decolonisation preparations included inviting foreign investors to establish locally based enterprises, to join the few forestry and plantation businesses (mostly owned by Westerners) and trading businesses (mostly owned by ethnic Chinese) [5].

At the same time it became clear that newly independent countries would be declaring two hundred nautical mile exclusive economic zones around their coastlines under the United Nations Law of the Sea, so Japanese fishing companies wanted to invest in local bases to secure their access to resources (Waugh 1994). Out of this confluence of interests Solomon Taiyo Ltd was established in 1973 as a joint venture between the Solomon Islands government and the fishing giant Taiyo Gyogyo (which changed its name to Maruha in 1993).

The most important market was the British tinned skipjack (a tuna-like species also called bonito) market. Solomon Taiyo was one of the few companies in the world that produced tinned skipjack according to the requirements of large British supermarket chains such as Sainsbury’s and Waitrose, which preferred high quality, socially and ecologically responsible products. Solomon Taiyo grew steadily over the years until by 1999 it had an annual turnover of around USD$100 million, employed close to 3,000 Solomon Islanders on its fleet of more than twenty fishing boats, and had a large shore base with a canning factory. At start up most employees had been Japanese nationals but over the years the proportion of Solomon Islander employees increased. In 1999 there were less than ten mainland Japanese managers, and around thirty Okinawan fishermen working for the company. Up to thirty technical positions were filled by short-term contractors from the Philippines and Fiji, but the rest of the workforce, including some senior management, most middle management and technical supervisory positions, were filled by Solomon Islanders. Since the mid 1980s the company had been 51 percent owned by the Solomon Islands government, with the Japanese partner company owning the remaining 49 percent of shares, and appointments to the Board of Directors were balanced between the two shareholders.

Solomon Taiyo’s main form of fishing was pole-and-line (called ‘poling’ in Australia and ipponzuri in Japanese) for skipjack. This is a low technology, high labor form of fishing with very low bycatch levels, and that can produce high quality meat. The skipjack fishery was in the open sea outside the reefs and lagoons. Solomon Taiyo’s pole-and-line fishery had an associated bait fishery to catch small shiny silver and Western fish that were ‘chummed’ (scattered) live across the surface above schooling skipjack to induce a feeding frenzy and encourage skipjack to snap at the shiny hooks on the lines. The baitfish were caught by bouke-ami nets at night in lagoons using lights to attract the fish. They were stored live in wells in the hold of fishing ships to be used the following day.

Solomon Taiyo’s mainland Japanese employees were mainly career managers seconded for periods of three to four years from Maruha. As a large company with a long history, Maruha has had the pick of the crop of young graduates from Japan’s fisheries-related universities. The importance of where young men went to school or university, generating a lifelong network of contacts [6], have been as important in gaining lifetime employment in Maruha as they have in any large prestigious Japanese company. In addition to the university graduates, some of Maruha’s managers were (high school graduate) fishermen who worked their way up the ranks to management positions. At least two managers involved with Solomon Taiyo over the life of the company were fishermen-managers. Maruha’s managers were organized into two streams, those who would spend their careers managing overseas operations around the world (fishermen-managers were in this group), and those who would rotate as managers overseas for five or ten years then return to Tokyo to act as central managers (Meltzhoff and LiPuma 1985). Solomon Taiyo’s managers had usually been of the first kind, but in the later years of the joint venture at least one manager with experience at Solomon Taiyo was promoted to a central management role in Tokyo [7].

Solomon Taiyo’s General Manager in 1999 had worked in Nigeria and Mozambique before being posted to Solomon Islands, with stints in the Tokyo office between each posting. The Operations Manager, the Fleet Manager and the Cannery Manager in 1999 were permanent Maruha employees, but were more or less permanently based at Solomon Taiyo. Two of these were married to Pacific Islander women. The Operations Manager had been working for Solomon Taiyo since the early 1970s and the Fleet Manager since the mid 1980s. The Cannery Manager had only been at Solomon Taiyo a couple of years, but before that had lived and worked in Fiji for many years. Other managers usually left their families in Japan while they worked overseas, for a variety of reasons including concerns about families being able to fit into the host society and about families being able to fit back into Japan when they returned, especially for children reaching middle school age, when school performance became vital for their future prospects.

Solomon Taiyo’s human resource management had always been affected by the intra Solomon Islands ethnic rivalries that had been exacerbated during the colonial era and left unresolved by successive independent governments. ‘Ethnic tension’ was the form in which a variety of dissatisfactions within contemporary Solomon Islands society (mostly about persistent failures and unevenness in economic development) came to be expressed. In late 1998 these dissatisfactions boiled over into widespread violence, particularly between the men of Guadalcanal and Malaita, and culminated in a coup in mid 2000. The government remained unstable until 2003 when the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands restored state control. The unstable business environment, however, coincided with a new purchasing strategy by main buyers in the UK, so the Japanese partner company withdrew from Solomon Taiyo in 2000. The then wholly Solomon Islands government owned company was renamed Soltai and reopened in 2001 [8].

Western and Islander representations of Japanese fisheries

Westerners who have worked closely with Japanese fisheries, such as government officials who work with Japanese government and company representatives on international fisheries issues, generally identify Japanese fisheries negotiators as ‘very tough’ but reliable in honoring agreements [9]. Such representations by well-informed commentators do not talk of a monolithic ‘Asian’ approach to fisheries, but distinguish Japan from countries such as Korea and Taiwan (and more recently China), seen as more prone to illegal fishing, breaking environmental laws and regulations, and mis-reporting catches (Schurman 1998).

General Western public opinion, however, has tended to categorize Japanese and Asian fisheries together as ‘bad’. Former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating accused both Japan and South Korea of illegal fishing, misreporting catches and under paying for catches (The Australian 1994), and Australian Senator Bob Brown has said of Japanese fisheries: ‘When it comes to marauding our oceans it seems the Japanese have no limits’ (Sforza 2006). English language representations of Japanese fisheries have often been negative, and often contrasted Japanese fisheries unfavourably with Western organizations.

[L]ocal fishing resources are flowing out of the countries concerned through the operations of the Japanese joint ventures. Also, the operation of the Japanese fishing companies never lead to the development of the local fishing industry and the development of local fishing technology… Do the Japanese firms feel responsible for the well-being of local employees and local economies? The obvious consequence will be that these Japanese firms will completely dominate the local markets and will control the prices of fish inside the countries… The Japanese government in January, 1979 gave Tonga and Western Samoa $750,000 worth of canned tuna in ‘grant aid.’ This ‘gift’ was made merely at the convenience of the Japanese fishing business and the Japanese government. The tuna skipjack industry, suffering from a slump, wanted the Japanese government to buy surplus canned tuna at the taxpayers’ cost, while the Japanese government suffering from surplus foreign exchange holdings wanted to abate its dollar reserve. This ‘gift’ also had the effect of imposing ‘canned food culture’ on the people of Western Samoa and Tonga. In sharp contrast with this selfish type of ‘aid’, we witnessed a really helpful kind of assistance provided by Denmark to Western Samoa… The Japanese fishing industry, unless it discards its arrogance and complacency, someday will certainly be carried out of the seas of the world (UNDP c.1983).

Solomon Taiyo was usually portrayed in English-language media as representative of these ‘bad’ Japanese/Asian companies. The kinds of practices of which Solomon Taiyo was often suspected included cheating the Solomon Islands government out of profits, treating Solomon Islander employees unfairly, colluding corruptly with government in development projects that bring no benefits to the general populace (Hviding 1996, 233), and fishing practices that were ecologically unsustainable, illegal and/or conducted without consultation with relevant village communities [10].

‘Here we go again. After the Asian plunder of Solomon Islands forests, its fishery is now under heavy attack… First they did it with forestry. Are they now doing it with fish?… Under pressure from aid donors disgusted by uncontrolled Asian plunder of the forests…’ (Islands Business 1996, 43).

This article was about events occurring in the early 1990s during the administration of the late former Prime Minister Mamaloni. First a joint venture called Makirabelle was started between Makira Province (Mamaloni’s home province) and a Philippines based company, Frabelle. Makirabelle asked for 35,000 metric tons from the national total allowable catch (TAC), so the TAC was increased by Cabinet from 75,000 to 120,000 metric tons. This TAC increase was not a problem because South Pacific Community tagging research indicated that an increase in Solomon Islands TAC to this level would probably be sustainable, and in any case despite the increased TAC the actual catch still did not exceed 70,000 metric tons. But Makirabelle had set a precedent and by 1995 there were numerous ‘joint ventures’, with Ministers and their wives on the Boards, and the TAC jumped to 500,000 metric tons, most of which was fortunately never caught.

The article cited two companies as ‘the good’ and four as ‘the bad’ of the Solomon Islands fishing industry during this period. ‘The good’ were Solomon Taiyo itself and another company National Fisheries Development (NFD), which for the first decade or so had substantial Japanese input via Solomon Taiyo. In 1999 NFD was owned by Singapore-based multinationally-owned company Trimarine. Solomon Taiyo and NFD were defined as good because they complied with local conditions for catch reporting, local employment and licensing fees. ‘The bad’ were joint ventures with two companies based in the Philippines, one in Thailand and one in Singapore, who apparently did not comply. Both ‘the good’ and ‘the bad’ companies, therefore, had Asian input, so the opening premise of the article that ‘Asian’ fisheries were resource plunderers does not fit the observable evidence. Such counterfactual representations may indicate that identity politics is involved, in this case an anti-Asian discourse about resource capitalism. In building an image of ‘Asian’ fishing as bad the article erased the Asianness of ‘the good’.

The negative tropes of Japanese/Asian fisheries as socially and ecologically unconcerned resource plunderers constitute a kind of Orientalism. The flipside of the negative tropes of Asian fisheries in this Orientalism is the construction of Westerners as ‘green’ and development-minded influences in the Third World. In this sense the identity ‘aid donor’ is interesting in the Islands Business article. Japan has been a major aid donor in the Pacific for some decades but the ideal aid donor the journalist had in mind was clearly not Asian, but probably Western. The Islands Business article represented bad Asian fishing companies being brought to task by good Western aid donors.

[A]s this abundant fishery is ‘discovered’ by more and more Asian ships moving ever southward, locals are noticing the impact of large fishing ships on their catches. A fisher of Lengana village explains: ‘The Japanese fleet gets permission from the [Solomon Islands] Fisheries Department. The boats come right close to the reefs where our people usually do their fishing. They don’t ask permission in the village; they just go there. And villagers are asking: ‘Why are these people fishing in our sea?’ They do not know that the sea is open and that Fisheries can just let anyone fish anywhere.’ He also objects to the way the outsiders fish: ‘The Japanese take thousands of fish of all kinds. They do not worry that in their nets are sharks and dolphins. There is nothing left for village people to catch. And the Japanese fleets do not want to share anything with the villager people. Normally if you fish on that reef, you must share your catch with the villagers. The village elders spoke strongly to them and pointed out their mistakes. So the Japanese people just give a bit of fish, not much. Locals are still angry, though’ (Kalgovas 2000).

This kind of representation of Solomon Taiyo’s activities was common in my interviews (the article was describing activities conducted by Solomon Taiyo alone). Like the Islands Business article, evidence to the contrary was overlooked in this narrative. Because Solomon Taiyo’s most important market was ecologically concerned British supermarket chains including Sainsbury’s, Solomon Taiyo had a commercial imperative to be ‘green’ and was actually not far from environmental best practice for an industrial fishing company. In 1999 the company was working towards achieving accreditation by the Marine Stewardship Council [11]. Skipjack are a resilient species and the pole-and-line method employed by Solomon Taiyo was not as ecologically destructive as other methods of industrial fishing.

Solomon Taiyo’s baitfishery, conducted on reefs and in lagoons, could potentially have depleted food fish stocks as asserted in the Kalgovas article. The perception that the baitfishery depleted food stocks in lagoons has existed since the earliest days of Solomon Taiyo (BSIP 1972b, 3; Bennett 1987, 336). Most Solomon Islanders I interviewed believed Solomon Taiyo’s baitfishing was depleting fish stocks in lagoons, and often expressed this by saying that small fish attract big fish, so by taking out too many small fish for bait Solomon Taiyo reduced the numbers of larger food fish available in the lagoons, and that that local fishers now had to go further off shore and fish for longer periods to get the same catch compared to the years before Solomon Taiyo started fishing [12]. But according to the Solomon Islands Fisheries Division and bodies such as the Australian Council for International Agricultural Research, that had researched the effects of Solomon Taiyo’s baitfishery on food fish stocks, the baitfishery was sustainable (Blaber and Copland 1990; Blaber, Milton and Rawlinson 1993; Solomon Islands Government 1986, 11, 13). Records of baitfish catch and effort dating from the start of Solomon Taiyo showed that Solomon Taiyo’s ‘catch per unit of effort’ in the baitfishery had remained stable, even in the most heavily fished areas [13].

The other contestable assertion in the Kalgovas piece is that Solomon Taiyo gave nothing in return for their baitfish catches, and that they refused to share the catch. The reefs and lagoons where villagers fished were considered customary land, and from the outset there was a royalty payment system administered by the Fisheries Division, by which Solomon Taiyo negotiated access and paid reef-owning villagers for the use of baitgrounds. It took several years for a workable system to be established, it was arguable that the royalties were very low, and there were ongoing arguments about which villagers had rights to receive the payments, but most Solomon Islanders were aware that the company could only fish in baitgrounds where access had been negotiated with landowners, and that the company paid royalties for fishing there. Furthermore, most Solomon Islanders were also aware that Solomon Taiyo vessels commonly gave away bycatch (non target species which had no commercial value to the company) to villagers, or exchanged fish for fresh fruit and vegetables.

If Solomon Taiyo’s fishing was sustainable, its nearshore fishing activities were negotiated with villagers who were paid for this access, and the company did share some of the catch with villagers, why did the opposite narrative persist in representations such as that in the Kalgovas piece? Part of the reason was that the Solomon Islands government and Solomon Taiyo failed to counter negative rumors about the company, and failed to disseminate information about the environmental impacts of its fishing activities, so the fact that Solomon Taiyo’s fishing was sustainable was not common knowledge. The arrangements for baitfishing were, however. Why, then, did Solomon Islanders make such representations, and why did Westerners such as Kalgovas accept these representations readily without verification? I propose that identity politics against Japanese fishing companies, and wider Asian resource capitalism, predisposed Western and Islander players to perceive the company negatively. Representations of Solomon Taiyo slotted into existing global discourses of Asian resource plunderers.

This kind of negativity regarding Solomon Taiyo resembles an earlier set of anti-Asian identity politics engaged in by Westerners in Solomon Islands. The majority of trading businesses in Solomon Islands have long been run by the local Chinese community, who came to Solomon Islands in the early colonial period as tradespeople, then later became traders. Before the Chinese trade stores were established, stores had been run by large companies such as Burns Philp and Lever Bros, or individual Western traders and planters. Chinese traders were unwelcome competition because they bought produce from locals at higher prices and sold goods to locals at lower prices than the big companies. Chinese shopkeepers built a better rapport with locals, socialized with locals more, and provided eating houses that were more affordable and comfortable for Solomon Islanders than the Western colonial clubs. In response, the big companies persuaded the colonial administration to disadvantage the Chinese traders. According to Bennett, as part of their campaign against Chinese traders, Western companies portrayed the Chinese as a bad moral influence on Solomon Islanders (Bennett 1987, 206-210). This seems to have been partly a conscious strategy to influence the government to restrict Chinese traders’ activities, but was probably also less consciously motivated by a sense of rivalry about who should bring ‘civilization’—as it was called in those days—to Solomon Islands. Eventually the large Western companies pulled out of trading and left it to the Chinese but Western representations of the Chinese as avaricious and exploitative of Solomon Islanders persisted. A 1975 report into foreign businesses in Solomon Islands corroborated Bennett’s finding that this reputation had no basis in historical fact, in finding that Solomon Islanders were ‘well served’ by their Chinese traders. Their prices were judged to be fair and the margins low (United Nations Development Advisory Team 1975).

Western representations of Chinese traders as preying on Solomon Islanders may be seen as part of a set of global English language anti-Asian discourses to which representations of Solomon Taiyo as a ‘bad’ company also belong. One manifestation of this discourse in Western representations of Solomon Taiyo was to contrast exploitative Asian/Japanese capitalism with benevolent Western capitalism. The main way this was done was through comparisons of Solomon Taiyo with the other large businesses in Solomon Islands, which were Western rather than Asian; Solomon Islands Plantations Limited (SIPL, a joint venture with the British Commonwealth Development Corporation, CDC); Kolumbangara Forestry Plantations Limited (KFPL, also with CDC); and Solomon Telekom (with a British telecommunications company). For example, a Western church leader who had lived in Solomon Islands for more than ten years, told me that Solomon Taiyo’s working conditions and housing were much worse than those of the other large joint ventures, that Solomon Taiyo gave nothing to the community compared to the other companies, and that Japanese managers did not care about their workers, because Japanese companies had little sense of social responsibility [14].

Interviews for this research and documentary sources from the Solomon Islands National Union of Workers (SINUW) showed that working conditions and remuneration of all of the large joint ventures including Solomon Taiyo were similar, around the national standard. Solomon Taiyo also donated money to various community sports facilities in Noro, and had a small project fund local villagers could apply to for community projects. According to a school teacher in Noro, Solomon Taiyo gave plenty of assistance to Noro school in comparison to the school KFPL workers used at Ringgi Cove [15]. Solomon Taiyo’s employee housing in the base town of Noro was abysmal; overcrowded, unsanitary and not maintained properly. This, however, was not solely the fault of the company but was also the responsibility of the Western Province government, which had reserved the right to develop Solomon Taiyo’s housing as its own business venture, yet never developed the housing properly. Unfavourable comparisons with the Western joint ventures on the grounds of social responsibility were thus like representations of ecological unsustainability. They contradicted the available evidence, leading to the conclusion that identity politics were involved.

Differences between Western and Islander representations

The examples of negative representations of Japanese fishing presented thus far may equally have come from Islanders or Westerners; interviewees from both groups said these kinds of things about Solomon Taiyo. Other representations, however, were more likely to come from one group or the other.

Many Westerners encountered during fieldwork refused to acknowledge any benefits from Solomon Taiyo to Solomon Islands. They downplayed benefits from employment by claiming that the pay and conditions were bad, that social benefits were counteracted by social breakdown caused by the company’s operations, and in any case came at the expense of the environment, or were only what was left after the Japanese partner siphoned off the profits. Many Islander interviewees, on the other hand, were more balanced in their assessments; at first portraying the company as bad, then qualifying this with positive comments, for example, that the company provided a lot of employment and training and that they liked the company’s products. Japanese manager Okubo suggested Solomon Islanders were more balanced in their assessments of Solomon Taiyo because most Solomon Islanders had either worked for the company themselves at some stage or a close relative had, so they had direct experience on which to base their opinions, whereas most Western people had no direct experience [16].

One of the Australian accountants who had worked for Solomon Taiyo, however, had a different explanation [17]. He felt that Western expatriates in Solomon Islands were so negative in their representations of Solomon Taiyo because they resented an Asian company bringing development to Solomon Islands. He thought Westerners saw themselves as having a special role as teachers of modernization to Solomon Islanders, and so were predisposed to disparage Solomon Taiyo.

In a broad sense, Japanese modernization has posed a challenge to Western identity as modern since at least the 1904 Russo-Japanese war. A sense of rivalry on the part of Westerners in relation to the Japanese capitalism is visible in a range of late twentieth century English language books about Japan, such as Ezra Vogel’s (1979) Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, Bill Emmot’s (1989) The Sun Also Sets: Why Japan Will Not Be Number One and William Nester’s (1990) Japan’s Growing Power Over East Asia and the World Economy. During and after the 1997 Asian Crisis, some Westerners triumphantly decried Japanese ‘crony capitalism’ (Milner 2000). Rivalry is also visible in some Western representations of Japanese modernity as having gone too far; a scary dystopia of overworked automatons and/or Blade Runner-esque cityscapes (Ueno n.d.), or of Japanese modern culture as ‘kooky’. The rivalry noted by the Australian accountant in Western representations of Solomon Taiyo as bad modernization could be seen as part of this broader rivalry with Japanese modernity.

Solomon Islanders did not share this sense of rivalry between modern peoples and have been subordinated by both Westerners and Japanese. The subordination of Solomon Islanders had its roots in British colonialism but also continued after Independence through dependence on aid and foreign investment. As Asian companies and governments became wealthier and more internationally powerful in the late twentieth century, the tendency of Solomon Islanders to identify as subordinate to Asians, including Solomon Taiyo’s Japanese managers, was strengthened (Tara Kabutaulaka c.1996).

As well as being less determinedly negative about Solomon Taiyo than Westerners, Solomon Islanders’ different subjective relationship to Japanese modernity was manifest in representations of Solomon Taiyo that attributed negative factors not to the company’s Japaneseness/Asianness (as implicitly or explicitly distinct from Western companies) but with its foreignness, which cast it into the same category as Western companies [18].

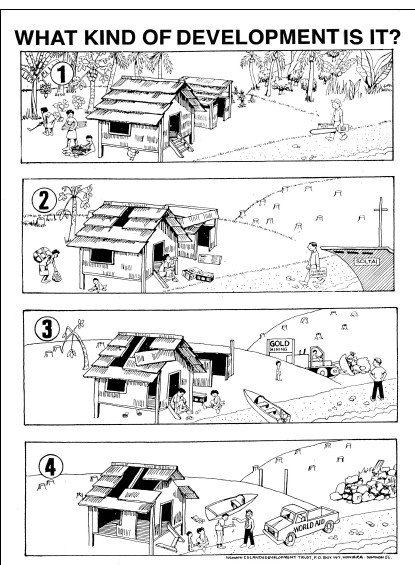

Previous researchers Metzhoff and LiPuma found in the 1970s that Solomon Islanders perceived the working conditions at Solomon Taiyo as being as bad as (not worse than) those at any other expatriate-run company (Meltzhoff and LiPuma 1983, 31), and many Solomon Islander interviewees in my research expressed similar sentiments. One local church leader who had worked for several years in Bougainville before working in Noro drew parallels between Solomon Taiyo and the Australian mining company in Bougainville [19]. Two Solomon Islander interviewees said they saw the behavior of Solomon Taiyo as following the pattern of any large multi- or transnational corporation, for example, through using overseas subsidiaries to control prices [20]. Other interviewees who worked for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) spoke of Solomon Taiyo as one of the overseas companies that gave money or ‘big fat promises’ to local people to make them forget the potential impact on their lives of environmental degradation [21]. Figure 1 is a poster produced by the local NGO Solomon Islands Development Trust (SIDT). It portrays Solomon Taiyo (frame 2) as one of the big companies of no specified nationality that has given villagers money for their resources—trees, fish, and gold—and then left villagers unable to feed or house themselves, resulting in aid dependency.

While some Solomon Islander representations of Solomon Taiyo thus portrayed Solomon Taiyo as a negative influence because it was foreign rather than because it was Asian or Japanese (as opposed to Western), some Solomon Islander representations were the same as Western representations in contrasting Solomon Taiyo negatively with Western-sponsored development projects. For example, Solomon Islander interviewees who worked for the Ministry of Finance and the Investment Corporation of Solomon Islands contrasted Solomon Taiyo unfavourably with the level of local management achieved in the British joint ventures [22]. Some of the passages presented earlier in this paper illustrate the point, with Islanders deploring the activities of Asian/Japanese resource plunderers compared to the activities of ‘good’ Western aid donors.

It is possible the trope of the Japanese/Asian resource plunderer has simply diffused into Solomon Islands understandings of peoples because it is so widespread in the English-speaking world, even though the subjectivity that generated the trope of bad Japanese modernity is one Solomon Islanders share. As noted earlier, Western-sponsored images of immoral exploitative Chinese traders took hold in Solomon Islander imaginaries throughout the colonial era and beyond, so it would not have been difficult for the slightly different image of the Asian resource plunderer to take root.

Another related explanation for anti-Asian/Japanese (rather than simply anti-foreign) representations of Solomon Taiyo by Solomon Islanders, is that Solomon Islanders may have been tapping into the Orientalist aspect of discourse of the Japanese/Asian resource plunderer specifically for a Western audience. This probably happened in interviews with me. Some Solomon Islander interviewees—knowing that Western people enjoy (or at least are predisposed to expect) the discourse of the Japanese/Asian resource plunderer—may have tailored their story to me as a Westerner. Some interviewees may have been telling me the story they thought I wanted to hear about Solomon Taiyo, a story that by implication painted Western development enterprises in a positive light.

This may have been behind the very negative (and inaccurate) picture of the company painted by the ‘fisher from Lengana’ in the Kalgovas (2000) piece quoted earlier. It could be that the fisher from Lengana’s representation that Solomon Taiyo fished without consultation with or recompense to villagers constituted a deployment of ‘weapons of the weak’ (Scott 1985). Creative manipulation of dominant groups’ discourses is one way for subordinated peoples to achieve their ends, and the playing off of dominant groups against each other is another useful strategy. For example, Acida Rita Ramos found that Indigenous Brazilians utilized divisions between groups of non-Indigenous Brazilians in order to gain media and political attention so as to create space to get a point across and to attract material support (Ramos 1998, 16, 98-101). During the Cold War some Pacific Island governments gained benefits from rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States, by resolving a standoff with the USA over fishing access fees in the late 1980s by granting access to Soviet fishing fleets, which made the support of Pacific Islands countries relatively more important to the US government than their domestic tuna lobby. Some Pacific Island countries, including Solomon Islands, continue to benefit from the rivalry between the People’s Republic of China and Taiwan. Perhaps the fisher from Lengana saw Western NGOs like the World Wildlife Fund (Kalgovas’ employer) as potential allies to gain leverage with Solomon Taiyo. The fisher from Lengana may have been engaging in pragmatic politics by appealing to internationally circulating negative images of Japanese fisheries in a story designed to spark Western NGO concern.

Japanese fisheries-related self-presentations

Solomon Taiyo’s Japanese managers were aware of their unflattering image in the minds of many Westerners and Solomon Islanders. The General Manager explained it by saying that Japanese people were not good at senden (public relations). Japanese managers’ self image in relation to Solomon Taiyo and Solomon Islanders was quite different to the image in Western and Islander representations. Japanese managers saw their role in Solomon Islands society through Solomon Taiyo in terms of the company being a development and modernization success story. As General Manager Komito left Solomon Taiyo to return to Tokyo in 1991, a newspaper report of his farewell speech listed some of the achievements of the company (Nius 1991, 9). The popular canned product Solomon Blue was being sold regionally and Solomon Taiyo had fulfilled its social obligations regarding employment, taxes and foreign earning. Indeed it excelled in terms of employment, being the only substantial employer of village women in the country. Komito was reported as saying Solomon Taiyo was the most successful tuna joint venture in the region, even the world.

When the former Mayor of Irabu (the town in Okinawa from which most of the fishermen employed by Solomon Taiyo came) visited other countries in the Pacific, all the government officials he spoke to said they wanted to start a company like Solomon Taiyo because it employed local people and the shore base was a permanent investment in the country [23]. The former Mayor had toured places in the Pacific where Irabu fishermen were employed, such as Papua New Guinea, and Mindanao in the Philippines. He described Solomon Taiyo as a model other countries wanted to follow. The Okinawan fishermen’s attitude to modernization was interesting in that Okinawa itself suffered internal colonialism within Japan, has remained economically disadvantaged and been denigrated by mainland Japanese in part for being ‘primitive’. The islands of Miyako, where Solomon Taiyo’s fishermen came from, were even more disadvantaged and were considered backward also by other Okinawans. Elsewhere I have discussed the Okinawan fishermen’s complicated perspectives on Solomon Taiyo as a modernization project (Barclay 2006).

As part of general public relations and corporate citizenship, Solomon Taiyo and its managers made donations to local charities (Nius 1988, 3; News Drum 1976, 2). Japanese managers also tended to view the company itself as a kind of charity. A Maruha employee in the Overseas Operations Section working closely with Solomon Taiyo described it as a ‘charity company’ [24]. In relating the history of Solomon Taiyo the General Manager said Maruha had not wanted to become a ‘charity company,’ Maruha would prefer that Solomon Taiyo was profitable. He said it was impossible to turn a good profit because the Solomon Islands government as co-owner had insisted on a shore base when the costs of doing business in Solomon Islands were high compared to major competitor country Thailand, and because the Solomon Islands government had no capital to invest in the company or utilities to support the shore base [25].

The Operations Manager’s version of the history of the company provided a different take on Maruha’s charitable motivations in Solomon. He said that the President of then Taiyo Gyogyo in the 1970s, Nakabe Kennichi, had visited Solomon Taiyo and told employees that Solomon Taiyo’s purpose was to ‘feed the people of the Solomons’. He told the managers to look after the Solomon Islanders, it did not matter whether Solomon Taiyo was profitable; the important thing was to keep the company going so that it could be of benefit for Solomon Islanders. In those days, according to the Operations Manager, the word of the President of the company was law, so this order from Nakabe was taken very seriously. When he died his son Nakabe Tojiro took over as President, and Tojiro felt Solomon Taiyo should continue to be managed according to his father’s wishes. The Operations Manager said that in the 1990s Maruha moved in the direction of requiring their overseas joint ventures to be profitable, but he believed there genuinely was a charitable motivation behind Taiyo Gyogyo’s involvement in Solomon Taiyo in the 1970s and 1980s [26]. Okinawan fisherman Ikema corroborated the Operations Manager’s story that the President of Taiyo Gyogyo had ordered Solomon Taiyo to feed the people of Solomon Islands, and this fisherman felt that through baitfishing fees and other benefits to Solomon Islands that Solomon Taiyo had fulfilled this promise to provide [27].

This identification on the part of the Japanese as charitable benefactors in relation to Solomon Islands is interesting. On one level it is a generous stance to take. But at the same time it is a profoundly dominant stance, one that is patronizing of Solomon Islanders. This identification is not of an equal partnership but involves self-identifying as having something the other lacks. Solomon Islanders had been feeding themselves perfectly adequately for thousands of years by the time Solomon Taiyo was established, what they lacked was the cultural capital and particular skills for building and maintaining a successful capitalist enterprise. Part of the dominance Japanese assumed in relation to Solomon Islanders through Solomon Taiyo was of moderns in relation to a ‘backward’ society.

None of the managers interviewed in 1999 labeled Solomon Islanders ‘backward’ or ‘primitive’, but in the 1970s and early 1980s Solomon Taiyo managers, like Western expatriates living in Solomon Islands, imagined Solomon Islanders, especially those living in villages, to be ‘primitive’. This (mis)understanding was then used to justify the crowded housing and monotonous food provided by the company, because managers felt that village life was no better (Meltzhoff and LiPuma 1983, 23).

By the later 1990s Solomon Islands’ lack of modernity was understood by Japanese managers in terms of an inhospitable environment for capitalism. This was often explained as a result of Solomon Islanders’ ‘traditional’ work ethic and the quality of government policies, but also in terms of other factors such as the distance from major trade routes making freight costs uncompetitive and necessitating the importation of many inputs. Japanese managers felt Solomon Islands’ difficult business environment was the reason Solomon Taiyo was unprofitable. One Maruha manager wrote that Solomon Taiyo could not ‘be competitive with merely her own power and capacity’, so the Japanese government must help with grant aid and low cost finance, and the Solomon Islands government must subsidize the company, for example, by requesting aid loans to pay for capital investment in the fleet (Tarte 1998, 124-126) [28]. This was in contrast to Solomon Islander and Western explanations for the lack of profitability, which often involved suspicions that Japanese managers were cheating Solomon Islanders of profit, for example, by transfer pricing through Maruha subsidiaries in order to avoid paying dividends or taxes in Solomon Islands.

Japanese managers knew that Maruha’s continued involvement in an unprofitable company aroused suspicions in Westerners [29]. In Western (particularly Anglo and North American) versions of capitalism profit is paramount. But in Japanese capitalism, at least until the 1990s recession, profit has been relatively downplayed and other factors, such as market share, have assumed relative importance. When I asked Maruha manager Shibuya about Solomon Taiyo’s lack of profitability, he answered that Solomon Taiyo had not made a profit because Japanese companies look after their employees properly, not like Western companies, which were quick to sack their employees rather than forfeit dividends for shareholders [30]. Technical reports on the management and financial structure of Solomon Taiyo (Hughes and Thaanum 1995; SPPF 1999) found that Maruha was acting in a characteristically Japanese way with cross shareholdings with an investment bank reducing the pressure for profitability, and factors other than profit motivating continued involvement, such as maintaining a supply of skipjack to facilitate important trading relationships. These reports found no evidence of unethical practices on the part of Maruha, and acknowledged the difficulties inherent in Solomon Islands’ business environment, but did not share the view of Japanese managers that it was impossible that Solomon Taiyo could be profitable, asserting that Japanese management had given up on the idea of profitability too easily, and not exhausted all avenues for improving profits.

Japanese management perspectives on Solomon Islands as being in need of charity were not nakedly racist, and were based in the frustrating reality of business life in Solomon Islands. At the same time, the representations also bolstered Japanese positions of authority and wealth in Solomon Taiyo by portraying (backward) Solomon Islanders as incapable of supporting a functioning business without (modern) Japanese assistance. The discourse of the charity company was closely related to developmentalist discourses revealed by critical development studies theorists in the 1990s as subordinating peoples identified as ‘underdeveloped’ to those who are seen to have achieved modernization and are thus identified as ‘developed’ (see for example, Sachs 1997; Manzo 1991; Hanlon 1998).

Japanese self-identification in the discourse of the charity company was a ‘good’ identity, in contrast to prevalent English language images of the ‘bad’ Japanese of Solomon Taiyo. Competitive identification as ‘good’ was also in evidence in narratives about the social and environmental practices of Japanese fisheries in contrast to American fisheries. Several Japanese interviewees compared Japanese tuna fisheries—employing the pole-and-line and longline methods, with a relatively small purse seine fleet made up of smaller capacity vessels—favorably against the mainly purse seine US fleet, which included vessels of very large capacity (and therefore potentially ecologically destructive efficiency) [31]. It was not just the environmental effects of purse seining that caused contention. The Japanese-favored pole-and-line method is very labor intensive, and so over a certain level of catch it is cheaper to use the very large purse seine ships with labor saving technologies. Since the 1990s purse seine caught tuna has therefore all but killed international markets for the more expensive pole-and-line caught skipjack, of which Japanese companies were the major producers.

Competitive self-identification as ‘good’ fishers compared to the US fleet had a history in the long running rivalry between Japanese tuna fishing companies and the American Tunaboat Association (ATA). Until the 1970s the Japanese fleet dominated the Western Pacific Ocean. Then towards the end of the 1970s the US tuna fishing fleet started to move west across the Pacific because of declining catches, disputes over dolphins, and deteriorating relations with Latin American governments in the East Pacific.

At this time newly independent island states were declaring 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) under the in-progress United Nations Law of the Sea, and demanding access fees from distant water fishing fleets. The US tuna lobby did not want to pay access fees and the US government supported them in this through a piece of domestic legislation called the Magnuson Act. Any country that impeded US tuna boats from fishing for highly migratory species (on the grounds that such species do not belong to any country) in their EEZ could have their trade to the US embargoed. Until the late 1980s US tuna boats fished illegally in the West Pacific, with US government support.

Japanese managers’ self identification in opposition to US tuna interests came to the fore in representations of a 1980s dispute about illegal fishing by a US purse seine vessel, the Jeanette Diana. In 1984 several Pacific Island countries became angry at illegal fishing by US purse seiners in their EEZs. The Jeanette Diana was a very large, high tech purse seiner with its own small helicopter to ‘spot’ schools of fish. The ship had been noticed in several places within Solomon Islands waters over a period of days, so the authorities sent out a patrol boat to request the Jeanette Diana to stop so they could board and check whether or not the ship had been fishing. When the Captain of the tuna boat refused to stop, the patrol boat fired shots across the bow of the tuna boat. The boat had been fishing, so it was impounded and the Captain was prosecuted. Under pressure from the American Tunaboat Association the Magnuson Act was activated and all trade from Solomon Islands to the US was embargoed. The only substantial trade from Solomon Islands to the US at that time was frozen fish sales from Solomon Taiyo to canneries in American Samoa and Puerto Rico. Suddenly Solomon Taiyo had to open new markets for their frozen fish in Thailand, which ruined the financial year for Solomon Taiyo [32]. The US government refused to acknowledge the findings of the Solomon Islands High Court that the Jeanette Diana had been fishing illegally. The Los Angeles Times quoted the Captain of the Jeanette Diana as saying ‘we realized we weren’t dealing with a rational government… the laws don’t mean anything to those people’ (Kengalu 1998, 170-171). Eventually the Jeanette Diana was sold back to the original owners (who were reimbursed by US taxpayers) in 1985 and the embargo was lifted.

Japanese fisheries people took the moral high ground over the unquestionably bad behavior of the US regarding EEZs in the Western Pacific. A Japanese media source described the US position on EEZs as contradictory because, although the government supported US boats fishing in the EEZs of other countries, the US coastguard prevented foreign boats from fishing in the US EEZ. This source said the US was ‘arrogantly subverting the rights and laws of another nation’ (Kengalu 1998, 171). Fuji Hiroshi, a manager in the Overseas Operations section in the Tokyo office of Taiyo Gyogyo, was reported by the Pacific Islands Monthly as having said ‘we are very unhappy about the manner in which these huge ships fish’ (Pacific Islands Monthly 1985, 41, 45). He estimated there were about 35 500 ton purse seiners based in Japan but in the USA there were many more even larger vessels, such as the 1,500 ton Jeanette Diana, which he thought were very environmentally destructive. Fuji hoped that the high operating costs of the very large vessels might drive them out of business. ‘The American policy about following migratory fish, regardless of exclusive economic zones, causes problems. It has led to disorder.’ Fuji said he was sure fish stocks would be depleted as a result. File material showed that Maruha and Solomon Taiyo managers repeatedly registered concern with the Solomon Islands government over protecting Solomon Islands’ skipjack stocks from purse seiners [33].

Solomon Taiyo’s Okinawan fishermen also expressed ill feeling towards Westerners about purse seining. Fisherman Toriike thought it hypocritical of Western organizations, such as Greenpeace, to oppose whaling and longlining but not purse seining, and thought the reason Greenpeace did not campaign for a ban on purse seining was because the American tuna industry was heavily involved and Greenpeace found it easier to target Japanese industries than American ones. He questioned American retailers’ marketing of purse seine tuna as dolphin-friendly when he felt the pole-and-line method (which he specialized in) was much more environmentally friendly than purse seining [34].

Conclusion

Western and Islander representations of Solomon Taiyo’s fishing practices often included suspicions of illegality and accusations of ecological unsustainability. These representations were quite inaccurate, in fact, Solomon Taiyo’s fishing practices were on the socially and ecologically responsible end of the spectrum of industrial fishery practices. This discrepancy between actuality and representation may be partly explained by a predisposition on the part of Westerners to view Japanese fishing practices negatively. Such representations of Solomon Taiyo drew on wider global discourses of predatory Japanese/Asian resource capitalism, which have as their flip-side the discourse of good Western capitalism. These English-language discourses filtered into Islander worldviews.

Some Solomon Islander representations of Solomon Taiyo’s fishing practices were more balanced than Western representations in presenting positive as well as negative images of the company. Some of the positive representations of the company by Islanders were in the vein of taking pride in having a large modern industrial enterprise in Solomon Islands. But most of the positive representations of Solomon Taiyo were buried in the detail of narratives that started off with unfavourable representations; despite containing positive representations the main discourse shaping those narratives was of bad Japanese capitalism. In contrast to Western representations that compared Solomon Taiyo unfavorably with Western companies, many Solomon Islander representations categorized Solomon Taiyo together with Western companies, both as big bad foreign businesses that dominated Solomon Islanders. These representations make sense in terms of Solomon Islanders’ history as a colonized people and contemporary status as ‘underdeveloped’, and which involves quite different experiences than Westerners in relation to the Japanese and modernity.

Some Solomon Islanders representations of Solomon Taiyo, however, were almost identical to Western representations. Some of this similarity in representations may be put down to simple diffusion of Western representations through the English language. Another explanation is that Solomon Islanders may have bought into the discourse of the Japanese/Asian resource plunderer in framing their representations for a Western audience. In some of these cases Solomon Islanders may have been representing Solomon Taiyo as a ‘bad’ company, in implicit contrast to ‘good’ Western companies, in order to leverage assistance from Westerners.

Japanese self-representations by contrast were of law-abiding, ecologically sound fisheries that involved the Japanese bringing modernization in the form of economic development to Solomon Islands. The identification as charitable benefactor towards Solomon Islanders was a dominant stance, just as Western identifications as teachers of development to the Third World have been. Self-presentations by Japanese fisheries people were often created in opposition to particular perspectives on US tuna fisheries as being ecologically irresponsible.

The contradictions between representations of Japanese fishing practices between Westerners, Islanders and Japanese may be seen as part of a wider rivalry between Japan and the West over competing modernity strategies, with Islanders having a third view based on experiences of pursuing their interests among powerful and wealthy foreigners.

Kate Barclay is a Senior Lecturer, Institute for International Studies, University of Technology Sydney. [email protected]. She wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on August 29, 2007.

References

AFP (2006) ‘Japan’s tuna quota slashed as punishment’, World News, Fish Information & Services, 17 October. Online. (accessed 19 April 2007).

Barclay, K. and Wakabayashi Y. (2000) ‘Solomon Taiyo Ltd: tuna dreams realized?’, Pacific Economic Bulletin, 15(10): 34-47.

Barclay, K. (2004) ‘Mixing up: social contact and modernization in a Japanese joint venture in Solomon Islands’, Critical Asian Studies, 36(4): 507-540.

—— (2006) ‘Between modernity and primitivity: Okinawan identity in relation to Japan and the South Pacific’, Nations and Nationalism, 12(1): 117-137.

—— (forthcoming) A Japanese Joint Venture in the Pacific: Foreign Bodies in Tinned Tuna, Oxford UK: Routledge.

Bennett, J. (1987) Wealth of the Solomons: A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978, Pacific Islands Monograph Series no. 3, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Berman, Marshall. (1982) All that is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Billig, Michael. (1995) Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

Blaber, S.M.J. & Copland, J.W. (1990) Tuna Baitfish in the Indo-Pacific Region, proceedings of a workshop, Honiara, Solomon Islands, 11-13 Dec. 1989. Canberra: Australian Council for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Proceedings no. 30.

Blaber, S.M.J., Milton, D.A. & Rawlinson, N.J.F. (1993) Tuna Baitfish in Fiji and Solomon Islands, proceedings of a workshop, Suva, Fiji, 17-18 Aug. 1993. Canberra: Australian Council for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Proceedings no. 52.

BSIP (British Solomon Islands Protectorate) 1972a, Governing Council Debates Official Report, 8th meeting, 6-27 November, Honiara: Government Printing Office.

BSIP (British Solomon Islands Protectorate) 1972b, Newssheet August, 17-31.

CCSBT (Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna) (n.d). Online. (accessed 19 April 2007).

Dikötter, F. (ed) (1997), The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Emmot, Bill (1989) The Sun Also Sets: Why Japan Will Not Be Number One, Simon & Schuster, London.

Escobar, A. (1997) ‘Planning’ in W. Sachs (ed), The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. London: Zed Books.

Fifi’i, J. (1989) From Pig Theft to Parliament. My Life Between Two Worlds, Honiara: Solomon Islands College of Higher Education and the University of the South Pacific.

Hanlon, D. (1998) Remaking Micronesia: Discourses over Development in a Pacific Territory, 1944-1982, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

Hughes, A.V. and Thaanum, O. (1995) ‘Costly connections: a performance appraisal of Solomon Taiyo Limited’, Forum Fisheries Agency, Honiara, Solomon Islands, Report No. 95/54.

Hviding, E. (1996), Guardians of Marovo Lagoon: Practice, Place, and Politics in Maritime Melanesia, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

Islands Business (1996) ‘Natural resources, here we go again’, December 22(12): 43.

Kalgovas, V. (2000) ‘The Shark’s Children’, New Internationalist, 325: 23-24.

Kengalu, A.M. (1988) Embargo: The Jeanette Diana Affair, Robert Brown and Associates, Bathurst, Australia.

Manzo, K. (1991) ‘Modernist Discourse and the Crisis of Development Theory’, Studies in Comparative International Development, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 3-36.

Meltzhoff, S.K. and LiPuma, E. (1983) A Japanese Fishing Joint Venture: Worker Experience and National Development in the Solomon Islands, International Centre for Living Aquatic Resources Management (ICLARM, now called WorldFish), Manila, Philippines, Technical Report 12.

Meltzhoff, S.K. and LiPuma, E. (1985) ‘Social organisation of a Solomons-Japanese joint venture’, Oceania, 56(2): 89-95.

Milner, A. (2000) ‘What happened to ‘Asian Values’?’, in Towards Recovery in Pacific Asia, G. Segal and D.S.G. Goodman (eds) Routledge, London, 56-68.

Nelson, H. (1982) ‘The Japanese 1942-1945: a note on the scale of the dying’, in R. J. May & H. Nelson (eds) Melanesia: Beyond Diversity, vol. I & II, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra, pp. 175-178.

Nelson, J.K. (2002) ‘Tempest in a textbook: a report on the new middle-school history textbook in Japan’, Critical Asian Studies, 34(1): 129-48.

Nester, William(199) Japan’s Growing Power Over East Asia and the World Economy, St Martin’s Press, New York.

News Drum (1976) ‘Farewell bicycle gift to Red Cross,’ Honiara, Solomon Islands, 11 June, 2.

Nius (1988) ‘Solomon Taiyo donates echo sounder to School of Marine and Fishing Studies’, Honiara, Solomon Islands, 3 October, 3.

Nius (1991), ‘Solomon Taiyo General Manager returns to Tokyo’, Honiara, Solomon Islands, 8 November, 9.

Pacific Islands Monthly (1985) July, 41, 45.

Ramos, A.R. (1998) Indigenism: Ethnic Politics in Brazil, University of Wisconsin Press, Wisconsin.

Sachs, W. (ed.) (1997) The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power, Witwatersrand University Press & Zed Books, Johannesburg & London.

Said, E. (1978) Orientalism, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Schurman, R.A. (1998) ‘Tuna Dreams: Resource Nationalism and the Pacific Islands’ Tuna Industry’, Development and Change, 29: 114-115.

Scott, J.C. (1985) Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sforza, Daniella (2006) ‘Japan caught up in a they-said-he-said battle over southern bluefin tuna’, World News, FIS Fish Information and Services, Thursday 17 August. (accessed 19 April 2007).

Shimizu Hiroshi (1997) ‘The Japanese fisheries based in Singapore, 1892-1945’, Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 28(2), 324-345.

Solomon Islands Government (1986) Annual Report 1985, Fisheries Division, Honiara.

SPPF (1999) Report on the Valuation of the Solomon Government Investment in Solomon Taiyo Limited. Sydney: South Pacific Project Facility (SPPF), International Finance Corporation, World Bank.

Tara Kabutaulaka, T. (c. 1996) ‘I am not a stupid native! Decolonising images and imagination in Solomon Islands’, unpublished paper, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University.

Tarte, S. (1998) Japan’s Aid Diplomacy and the Pacific Islands, Canberra, Australia: Asia Pacific Press.

The Australian (1994) Tuesday 2 August, 12.

Torgovnick, Marianne (1990) Gone Primitive: Savage Intellects, Modern Lives. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

White, G. and Laracy, H. (eds) (1988) ‘Taem blong faet: World War II in Melanesia’, special issue of O’O Journal of Solomon Island Studies, 4.

Wilkin, S. (2001) ‘Unsticking Japan: companies must be pushed to stop wasting capital’, Asiaweek, 30 March – 6 April, 19.

Ueno T. (n.d.) ‘Japanimation and Techno-Orientalism: Japan and the Sub-Empire of Signs’.

United Nations Development Advisory Team (1975) ‘Foreign Firms in the Solomon Islands Economy,’ Suva, Fiji.

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (c.1983) ‘Japanese Joint Ventures in the Pacific’, in unpublished report Fisheries in Asia: People, Problems and Recommendations, Forum Fisheries Agency (Honiara): EL/3.10, Solomon Taiyo correspondence.

Vogel, Ezra (1979) Japan as Number One: Lessons for America, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass.

Waugh, G. (1994) ‘Economics and Politics of Tuna Fisheries in the South Pacific’, in H. F. Campbell & A. D. Owen (eds) Economics of Papua New Guinea’s Tuna Fisheries, Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, 12-21.

Notes

[1] This research was part of doctoral work undertaken through the Institute for International Studies at the University of Technology Sydney. An earlier version of this chapter was presented at the 2003 IIS annual research workshop, where Elaine Jeffreys, Bronwen Dalton, Ilaria Vanni and Guo Yingjie provided helpful comments. The ideas were further refined during a postdoctoral fellowship at the Crawford (formerly Asia Pacific) School of Economics and Government at the Australian National University, and presented again at the 2005 biennial conference of the Japanese Studies Association of Australia in Adelaide, South Australia. Thanks also to Mark Selden, Hirokazu Miyazaki and Chris Nelson for suggestions for improvements to the paper.

[2] The conceptualization of identity and modernity in this paragraph borrows from an earlier paper (Barclay 2006).

[3] Elsewhere I give an expanded explanation of connections between the various ideas tied together here as modernism and their relation to the study of identity (Barclay forthcoming).

[4] Interview with Hirara in his office, 4 November 1998, Miyako Island, Okinawa. The Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Technology Sydney required that participants in this research remain anonymous. For that reason in this paper interviewees are referred to, not by their real names, but by place names. Okinawan interviewees have been given names of places in the Miyako Islands, Japanese mainlander interviewees are referred to by place names from the mainland, Solomon Islander interviewees are referred to by place names from the Solomons, and Westerners have place names from Australia. Interviews with Sarahaman fishers and Japanese managers were conducted in Japanese. Interviews with Solomon Islanders were conducted in English or Pijin. Translations into English are my own unless otherwise specified.

[5] Solomon Islands was (and largely remains) a non-capitalist society with up to 90 per cent of the economy existing in the non-cash sphere. For a thorough discussion of the economic history of Solomon Islands since Western contact see Bennett (1987).

[6] For an example of how important such university contacts were in Japanese fisheries businesses in Southeast Asia in the early twentieth century see Shimizu (1997).

[7] Japanese manager Shibuya had worked in Solomon Taiyo twice, once as Financial Manager, then as General Manager in the 1990s, and also been posted more than once to the Overseas Operations section in the Tokyo office that dealt with Solomon Taiyo, among other joint ventures. Later he was promoted to Department Chief (bucho) of a central planning and finance department.

[8] Although wholly nationally (government) owned, Soltai has remained dependent on international capital, expertise and trade networks (Barclay 2005).

[9] This reputation has been damaged by the 2006 exposure of Japan’s long-running underreporting of southern bluefin tuna catch while being a dominant player calling for ecological responsibility within the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna. See CCSBT (n.d.) and AFP (2006).

[10] Interview with Ndunde at his home, 13 June 1999, Munda, Solomon Islands.

[11] The Marine Stewardship Council

[12] For example, Interview with Ilangana at Agnes Lodge, 3 June 1999, Munda, Solomon Islands; Interview with Kazukuru at her home, 12 June 1999, Munda, Solomon Islands. Factors that could have contributed to the perceived drops in food fish stocks include pollution and overfishing from rapidly growing coastal communities. Interview with Vangunu at the Fisheries Division offices, 11 August 1999, Honiara, Solomon Islands; National Fisheries Workshop held at the King Solomon Hotel in Honiara in July/August 2005.

[13] For further details on the baitfishery and its sustainability see Barclay (forthcoming). Interviewees often asserted that Solomon Taiyo falsified baitfishing records so as to pay lower royalties, but from 1981 the system of monitoring baitfish catches for the purposes of stock assessments and payment of royalties to baitground owners had been designed to remove incentives to underreport by de-linking calculations of catch from calculations for payment, and enabling villagers to monitor activities for which they should be paid. Fisheries Division interviews and records contained no indications that Solomon Taiyo had falsified baitfishing records (Fisheries Division [Honiara]: RF 8/2, correspondence; Fisheries Division [Honiara]: F 8/6, correspondence; Blaber and Copland 1990; Blaber, Milton and Rawlinson 1993).

[14] Interview with Brisbane at the Noro Town Council, 23 June 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[15] Interview with Baru at Noro Primary School, 16 July 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[16] Interviews with Okubo in Solomon Taiyo offices several times April-July 1999, Honiara and Noro, Solomon Islands.

[17] Interview with Sydney at his home office, September 1999, Sydney, Australia.

[18] I have elsewhere discussed Solomon Islanders’ aversion to domination by foreigners as an aspect of the identity relations of Solomon Taiyo (Barclay 2004).

[19] Interview with Bougainville at Noro Town Council, 22 June 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[20] Interview with Choiseul at his home 20 May 1999, Honiara, Solomon Islands; interview with Roviana at Noro Town Council several times June-July 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[21] Interview with Panatina at the office of the Young Women’s Christian Association, 23 April 1999, Honiara, Solomon Islands; interview with Bellona at the office of the Development Services Exchange, 29 April 1999, Honiara, Solomon Islands.

[22] Interview with Borukua and Maramasike at office of the Investment Corporation of Solomon Islands, 10 August 1999, Honiara, Solomon Islands.

[23] Interview with Nakachi in the Fisheries Promotion Section office at Sarahama, 10 November 1998, Irabu Island, Okinawa.

[24] Interview with Shibuya in Maruha Head Office in Otemachi January 1999, Tokyo, Japan.

[25] For further details on the cost structure and profitability of Solomon Taiyo see Barclay and Wakabayashi (2000).

[26] Interview with Osaka on the Solomon Taiyo Base several times June-July 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[27] Interview with Ikema in his home, 5 November 1998, Irabu Island, Okinawa.

[28] Fisheries Division (Honiara): RF 8/2, correspondence, letter dated 3 Feb. 1997; Forum Fisheries Agency (Honiara): EL/3.2, Solomon Taiyo correspondence, letter dated 1 Aug. 1994.

[29] Interview with Osaka on the Solomon Taiyo Base several times June-July 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.

[30] Interview with Shibuya in Maruha Head Office in Otemachi January 1999, Tokyo, Japan.

[31] Pole-and-line fishing involves poles with fixed lines and barbless hooks. The hooks are dipped into the water amongst schools of fish, from the side of the boat, and snagged fish are flicked up over the head of the fisher to land behind on the deck. The longline method uses a long line dropped out in the ocean dragging behind a fishing vessel. Short lengths of line with hooks dangle from the long line. The long line is reeled back into the vessel and snagged fish pulled aboard. Purse seine vessels have a large net they drop behind into the water, then run in a circle to make a tube of net vertical in the water, then pull the bottom shut like a purse, and the surrounded fish are pulled aboard with the net.

[32] Interview with Shibuya in Maruha Head Office in Otemachi January 1999, Tokyo, Japan.

[33] Forum Fisheries Agency (Honiara): EL/3.10, Solomon Taiyo correspondence.

[34] Interview with Toriike, at the Okinawa Rest House, 26 July 1999, Noro, Solomon Islands.