Rejected by All Plaintiffs: Failure of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa “Settlement” with Chinese Forced Laborers in Wartime Japan

Kang Jian[1] with an Introduction by William Underwood

This is Part One of a two-part series. Part Two is available here.

A Chinese version of this article is also available.

Introduction

Japanese lawyers and activists supporting compensation lawsuits for Chinese forced labor in wartime Japan once called Chinese attorney Kang Jian the “window.” The term acknowledged Kang’s pivotal role in coordinating between plaintiffs typically located in the Chinese countryside and Japanese legal teams pressing claims on their behalf in a dozen courtrooms across Japan over the past decade.

However, the close cooperation between Kang and the Japanese Lawyers Group for Chinese War Victims’ Compensation Claims broke down in April 2010, at least temporarily, following the out-of-court compensation agreement by Nishimatsu Construction Co. with forced laborers from its Shinanogawa worksite in Niigata. Late in the process of hammering out the settlement fund worth 128 million yen (about $1.28 million), the five plaintiffs’ Japanese lawyers began negotiating with Nishimatsu on behalf of the larger group of Shinanogawa victims who had not participated in litigation. Flanked by Kang, these five plaintiffs rejected the Nishimatsu pact at a press conference in Beijing the day after it was finalized in Tokyo.

Attorney Kang in the article below severely criticizes the twin pillars of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa accord: the Japan Supreme Court’s ruling in 2007 that the 1972 treaty between Japan and China extinguished the right of Chinese citizens to seek war-related damages, and Nishimatsu’s insistence that it bears no legal liability for wartime forced labor. The article also suggests deeper questions about the justice of group settlements for historical wrongdoing that include symbolic compensation to victims who have not agreed with settlement terms in advance.

Kang raised similar objections in a previous Asia-Pacific Journal article about Nishimatsu’s first voluntary settlement last October with Chinese laborers from its Yasuno worksite in Hiroshima, following one of the few lawsuits in which neither Kang nor the main Japanese lawyers group was involved. (See Redress Crossroads in Japan: Decisive Phase in Campaigns to Compensate Korean and Chinese Wartime Forced Laborers for recent developments involving forced labor redress for Chinese, Koreans and Allied POWs.)

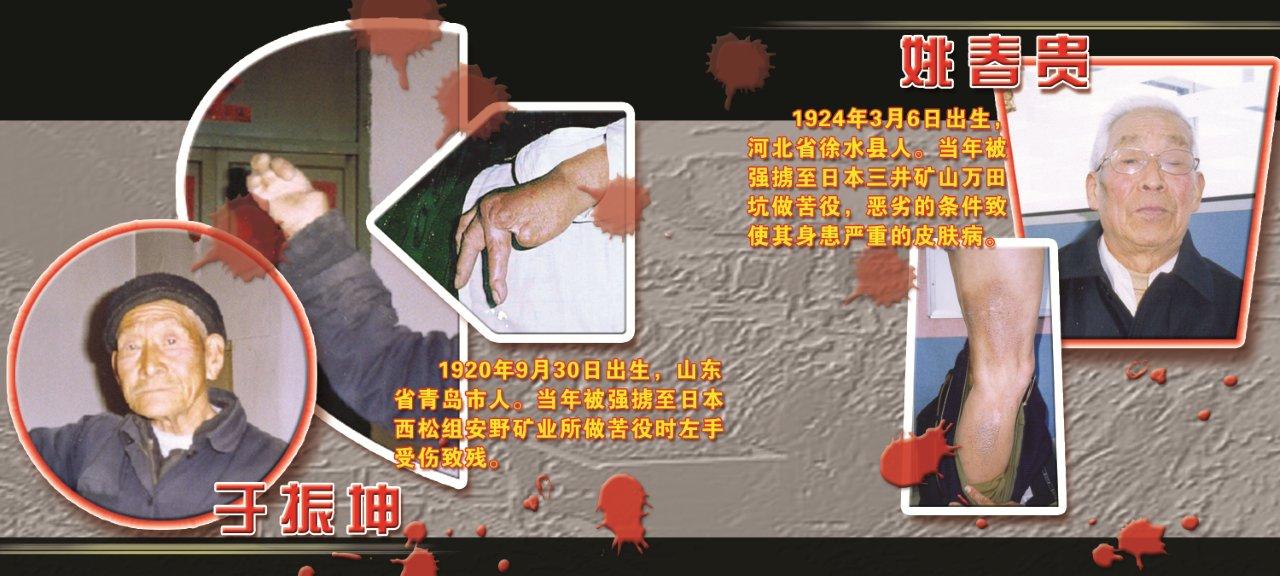

The reparations claim for Chinese forced laborers remains particularly compelling and potentially resolvable. Many victims were farmers abducted from their fields by Japanese soldiers in the final two years of the war, and then taken to Japan for harsh labor at corporate-owned worksites with fatality rates of up to 50 percent. There were 38,935 workers according to detailed records that were secretly produced by the Japanese government in 1946, and then suppressed or destroyed once the very real threat of widespread war crimes prosecutions had blown over. The 35 companies involved received postwar indemnification payments from the state for losses supposedly incurred, even though wages were almost never paid during the war. Less than 1,000 former workers are believed to be alive today and their identities (if not in all cases exact locations) are well known.

Most significantly, Japanese courts in recent years have established the forcible, illegal nature of the Chinese labor program beyond any doubt, and ruled that it was jointly carried out by the Japanese state and industrial sector. Prior to the “death-knell” decision by the Japan Supreme Court in 2007, lower courts usually let the government and corporations off the legal hook on the respective grounds of state immunity and time limits for filing claims. Yet even in rejecting lawsuits Japanese judges on multiple occasions recommended that non-judicial avenues of redress be explored, while four actual courtroom victories infused Chinese forced labor redress efforts with a rare sense of legal momentum.

The Tokyo District Court in July 2001 ordered the state to pay the family of Liu Lianren for the 13 years he spent in hiding after he escaped from a Hokkaido mine just before the war ended. The Fukuoka District Court in April 2002 described Mitsui & Co.’s conduct as “evil” and ordered the company to compensate plaintiffs. The Niigata District Court in March 2004 found both the state and the transport company Rinko Co. liable for damages. The Hiroshima High Court in July 2004 ordered Nishimatsu to compensate plaintiffs from the Yasuno site.

The last was the ruling overturned by the Supreme Court on treaty-based grounds, ensuring that neither the Japanese government nor the companies will ever be required by Japanese courts to pay damages to Chinese claimants. It was a highly orthodox and largely expected decision by the top court, even if the claims waiver language in Japan’s 1972 treaty with China was (for reasons related to Japan’s 1952 treaty with Taiwan) more ambiguous than that found in treaties with the Allied nations in 1951 or with South Korea in 1965.

Basically all of the myriad legal claims against Japan arising from war and colonialism have now been dismissed by the top courts in Japan and/or claimants’ own countries, reflecting the nation-centric interpretations of international law that currently prevail. This means that war redress demands have per force moved into the political, economic and moral arenas, with legislative action having emerged within an ongoing global trend as the most effective means of repairing past injustices.

In the case of Chinese forced labor, the best way forward might be for the generally ambivalent Chinese government to bring more pressure to bear on the Japanese government and the corporate users of forced labor that are becoming increasingly dependent on the Chinese market. If China were to permit compensation lawsuits to proceed in Chinese courts, for example, the public relations fallout would probably send major companies like Mitsubishi Materials to the negotiation table even if the suits were never actually adjudicated. Mitsubishi is today a prime target of attorneys and citizens groups in both China and Japan, as the firm has indicated its willingness to settle Chinese claims on the condition the Japanese government participates in the process.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, meanwhile, announced in July 2010 that it would open compensation talks with Korean women deceived as teenagers into working without pay at its wartime aircraft factory in Nagoya. That surprise move in the teishintai (or “volunteer corps”) case came only after many years of grassroots activism, first by Japanese and later by Koreans, as well as direct involvement by Seoul authorities in the form of the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization Under Japanese Imperialism. Mitsubishi’s resistance to addressing the teishintai matter was finally broken by a petition signed by more than 130,000 South Korean citizens and 100 members of the National Assembly – along with a credible threat of organized consumer boycotts.

Japanese attorney Takahashi Toru has told The Asia-Pacific Journal that the Lawyers Group for Chinese War Victims’ Compensation Claims plans to meet soon with the 20 or so still-extant companies that used Chinese forced labor, to encourage them to follow the Nishimatsu example. Two firms, Hazama Co. and Tekken Construction Co., were co-defendants with Nishimatsu (and the Japanese state) in the Shinanogawa lawsuit, but have taken no steps toward reconciliation. It is hoped that a critical mass of these Japanese companies will eventually recognize that resolution of the Chinese forced labor issue is in their corporate self-interest, and that they will in turn help persuade the Japanese government to set up a comprehensive state-industry compensation mechanism just as Germany did in 2000.

Prior to assuming the reins of power one year ago, the Democratic Party of Japan had established a party subcommittee for addressing the Chinese forced labor problem, along with subcommittees for issues involving Allied POWs and the repatriation of war-related remains. The DPJ also campaigned on proactively settling historical matters that had festered during a half-century of rule by the Liberal Democratic Party. But meaningful legislative or administrative action on forced labor by Japan will not occur unless the DPJ, which fared poorly in July’s national elections, can consolidate its political position, or in the absence of significant domestic and/or international pressure on the issue.

Given both the Japan Supreme Court ruling and the German precedent, future Japanese measures concerning Chinese forced labor, at the state or corporate level, will almost surely be couched in moral and humanitarian—not legal—terms. Upcoming agreements likely will be explicitly premised on the April 2007 ruling and a denial of legal liability by the Japanese side, and it is the inclusion of these premises in the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa deal that is Kang Jian’s central objection in the article that follows. The reparations road ahead may, however, involve both Japanese government creation of a framework for settlement and corporate payments to victims.

Kang’s voice is that of a ground-floor participant and major figure in a transnational movement and legal process now approaching a decisive stage. Her important role of many years in fighting for justice for Chinese forced laborers, and her influential position in Chinese legal circles, entitle her views to a respectful hearing. –William Underwood

**************************

On April 26, 2010, Japan’s Nishimatsu Construction Corporation (hereafter called Nishimatsu) and descendants of a number of Chinese victims of wartime forced labor at the Shinanogawa worksite in Japan signed an out-of-court settlement agreement. Some media phrased this action as “Nishimatsu arrived at a settlement with the Chinese forced laborer plaintiffs“, or “Nishimatsu will pay damages to 183 Chinese victims of forced labor“.

The truth is that all the plaintiffs of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa forced labor lawsuit in Japan, who were confirmed by both Nishimatsu and the plaintiffs’ Japanese attorneys in June 2009 as the representatives to negotiate with the company, did not sign any settlement agreement with Nishimatsu. The root cause for this are: (a) Nishimatsu insisted to state in the content of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement[2] that “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived”, but did not allow the plaintiffs to express side by side in the Settlement Agreement that they could not accept this wrong viewpoint; (b) In order to make clear its unyielding position of not taking any legal liability, Nishimatsu deliberately uses the term “atonement money (償い金)” to ambiguously name the damages that they should have paid to the Chinese victims; and (c) Moreover, Nishimatsu unreasonably requires those who accept the “settlement” to bear hereafter the obligation of ensuring that the corporation will be immune from any future liability from any other parties for this case. This article discusses these and other shortcomings of the unacceptable “settlement” in detail.

The position of rejecting the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement by all plaintiffs is supported by many concerned individuals and organizations including Canada ALPHA (Association for Learning and Preserving the History of WWII in Asia).[3]

1. Initiation of the settlement for Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa forced laborer lawsuit

Han Yinglin (deceased on June 7, 2010), Hou Zhenhai (deceased), Guo Zhen (deceased), Li Shu (deceased), and Li Xiang (deceased)[4] are five of the victims of wartime forced labor who were abducted to Nishimatsu’s Shinanogawa worksite in Niigata Prefecture of Japan for hard labor in 1944. At the Tokyo District Court on September 18, 1997, they sued the Japanese government, Nishimatsu, Hazama Co. and Tekken Construction Co. for abduction and enslavement, demanding that the defendants openly apologize to the Chinese victims in both Chinese and Japanese media and pay each plaintiff damages of 20 million yen.

On March 11, 2003, the Tokyo District Court made the judgment of the first trial. The Court did not verify the facts of perpetration and dismissed the claim of the plaintiffs on the ground of statutory time limit.

The plaintiffs appealed immediately. On June 16, 2006, the Tokyo High Court made the judgment of the second trial. The court verified in detail the facts of victimization presented by each of the plaintiffs and the tortuous acts jointly committed by the State of Japan and the Japanese corporations, in which they abducted and enslaved the Chinese victims of forced labor. The plaintiffs’ claim, however, was dismissed again on the ground of statutory time limit.

The plaintiffs then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan. On June 15, 2007, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court summarily dismissed the appeal of the plaintiffs without citing any legal grounds.

In 2009, senior officials of Nishimatsu were investigated by Japanese authorities for illegal political contributions and the senior management was then reorganized. In consideration of the corporation’s business strategy and other factors such as improvement of its public image, Nishimatsu expressed in May 2009 its wish to resolve the historical issue by settling out of court with the Chinese victims of forced labor at its Shinanogawa worksite (as well as victims from the separate Yasuno worksite). The Chinese victims responded positively to this. In June 2009, the author went to Tokyo in the capacity of agent for the Chinese plaintiffs from Shinanogawa and, together with the Japanese lawyers who represented the Chinese plaintiffs, negotiated with Nishimatsu.

At that time, the Nishimatsu representatives indicated that they would handle this case following the Hanaoka “settlement” model. The author unambiguously expressed that the Hanaoka “settlement” model should not be used because the Hanaoka “settlement” was characterized by the following features: the Kajima Corporation that enslaved the Chinese forced labor victims at its Hanaoka worksite evaded the facts of perpetration, evaded its responsibility, gave charitable “relief” to the Chinese forced labor victims to terminate its legal liability, and crowned the charitable relief fund with the laurel of “Friendship Fund”. In addition, the Hanaoka Settlement Agreement contains a provision that inappropriately restricts the rights of any third party, including those who refuse to accept this “settlement”, to claim damages from Kajima, the perpetrating corporation.

As the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa settlement negotiation stemmed from the lawsuit claims for damages by the plaintiffs, both parties established the principle at the initial stage of negotiation that the plaintiffs in the litigation be the representatives of the victims’ side throughout the negotiation.

A few months later, when proposing the settlement provisions, Nishimatsu insisted on including in the settlement agreement the wrong judgment made on April 27, 2007, by the Supreme Court of Japan. In that landmark ruling, the court held that the Chinese people’s right to claim for damages had been waived in 1972, yet it also stated there is an expectation that the Chinese plaintiffs be given appropriate relief. Nishimatsu has taken this ruling as the premise for making a settlement with the Chinese victims of forced labor.

As representatives of the Chinese forced labor victims of the Shinanogawa worksite at the negotiation, all the plaintiffs made clear that the wrong conclusion derived from the unilateral interpretation of the China-Japan Joint Communique of 1972 by the Supreme Court of Japan should not be written into the Settlement Agreement. In compromise and to allow the opposite positions of the two sides on this issue to be expressed, the plaintiffs proposed that the Chinese victims’ position of not accepting that “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived” should also be written into the same provision of the Settlement Agreement. Another proposed option was moving this controversial content from the Settlement Agreement to the Confirmation Items document. Nishimatsu rejected the plaintiffs’ proposals categorically.

2. Nishimatsu’s intention to insist that “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived” as the premise for settlement

The Chinese victims of Japan’s war of aggression against China brought over 20 legal claims for damages, one after the other, to Japanese courts against the Japanese government and corporations. The Japanese courts that undertook the trial of these cases had made many rulings already before April 27, 2007, but none of these judgments ruled that the Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived.

On April 27, 2007, the Supreme Court of Japan made a ruling (hereafter called the 4/27 ruling) on the Nishimatsu-Yasuno forced labor case, deciding that the government of China, on signing the China-Japan Joint Communique, had waived fully the right to claim, including that of the Chinese nationals.

On the same day that the Supreme Court of Japan made the ruling, the spokesperson of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a firmly worded statement expressing explicitly that “the interpretation of the China-Japan Joint Communique made by the Supreme Court of Japan is illegal and invalid.”

After the 4/27 ruling was made, some Chinese and Japanese scholars of law and history studied and discussed the court ruling. They arrived at a common understanding that it is an obvious violation of the basic principle of international laws for the Supreme Court of Japan to use the San Francisco Peace Treaty, to which China was not a party, as its framework to unilaterally interpret the China-Japan Joint Communique and to rule that “Chinese people’s right to claim for damages from Japan had been waived”. Thus, the court’s conclusion that “Chinese people’s right to claim for damages had been waived” cannot be established. How to correct this wrong ruling will become a major issue from now on for both China and Japan in relation to finding ways to truly resolve the wartime legacy.

In June 2007, when the Supreme Court of Japan dismissed the appeal of the plaintiffs of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa forced labor case, it did not give any reason and only simply stated in a few lines that the appeal was dismissed. The verdict did not mention anything at all about “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived”. Hence, the ruling of the second trial at the Tokyo High Court on the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa forced labor case came into effect. In its verdict, the Tokyo High Court affirmed in detail the facts about the sufferings of Han Yinglin and the other four plaintiffs, affirmed also the illegal acts committed against the Chinese forced labor victims by the Japanese government, Nishimatsu and other perpetrating corporations. This court dismissed the victims’ claim on the ground of exceeding the time limitations and the repose period for filing suit, but it did not rule that the Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived. The Japanese lawyers who represent the plaintiffs also agree with the above analysis of the course of events.

If Nishimatsu really has the sincerity to make a settlement with the Chinese victims of forced labor, and if the company must cite a Japanese court ruling as a preamble of the Settlement Agreement, then the logical choice should be the verdict of the second trial made by the Tokyo High Court. Nishimatsu, however, insisted on quoting the 4/27 ruling, which was not specifically made for the Shinanogawa case. The reason for this choice is self-explanatory. It is precisely because this 4/27 ruling decided that the “Chinese people’s right to claim damages from Japan had been waived”.

The Yasuno Settlement Agreement signed on October 23, 2009, between Nishimatsu and some Chinese forced labor victims and their descendants of the Yasuno worksite also included similar content asserting that “Chinese people’s right to claim damages had been waived”.

Nishimatsu insisted to insert also in the Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement the 4/27 ruling. Its intention is to forcibly establish a “settlement” model on the premise that “Chinese people’s right to claim damages had been waived”. This “settlement” model is to help the Japanese side to evade legal liabilities regarding their serious violations of human rights and international laws.

This “settlement” model will also produce another effect: Although various spokespersons of the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs repeatedly denounced the wrong rulings made by the different levels of Japanese courts on or after April 27, 2007, the fact that there are Chinese victims who accept settlement agreements based on this model implies that they accept the wrong rulings regarding “Chinese people’s right to claim damages had been waived”. The construction of this reality will inevitably have adverse impacts on the resolution of war legacy issues.

3. Plaintiffs being involuntarily and forcibly included as part of the “Settlement” defined by Nishimatsu

Ignoring the principle of reciprocity, Nishimatsu insisted on writing into the Settlement Agreement that “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived” and objected to the inclusion of the plaintiffs’ position of not accepting the 4/27 ruling in the same provision. In the spirit of compromise, the plaintiffs then proposed moving all such contents to the Confirmation Items document, but even this rightful demand was rejected by Nishimatsu. According to the Japanese lawyers of the plaintiffs, the President of Nishimatsu had explicitly stated that not a single word of the Settlement Agreement (the version finalized in December 2009) would be changed, and that the lawyers could write whatever they liked in the Confirmation Items because after all the President would not sign on the Confirmation Items document. This confession of the President indicates that Nishimatsu has no intention to truly reflect on the facts of perpetration or to sincerely apologize. It also shows that Nishimatsu knows the difference in terms of legal status between the Settlement Agreement and the Confirmation Items document.[5]

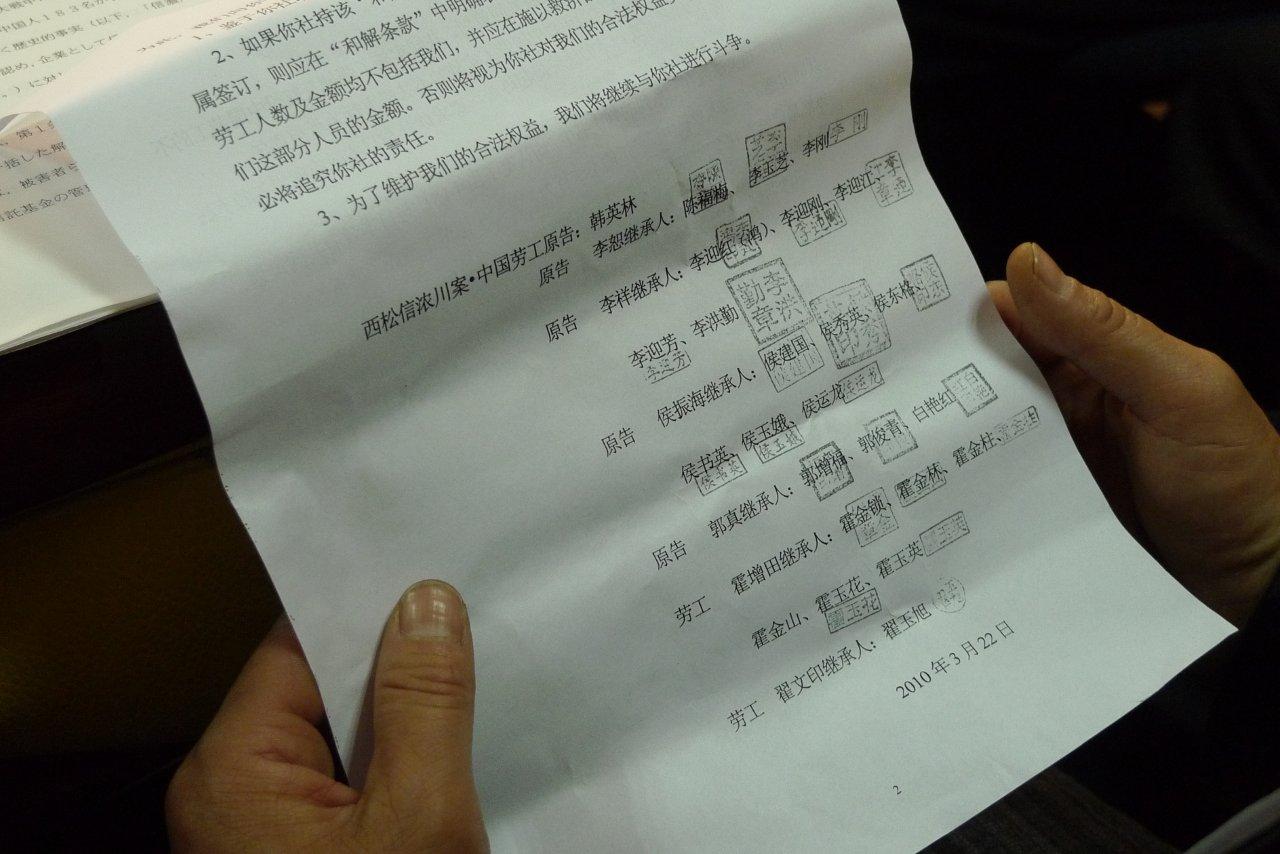

On March 22, 2010, all the plaintiffs who had been confirmed as the representative body at the beginning of the negotiation with Nishimatsu, issued a statement rejecting the insincere Settlement Agreement offered by Nishimatsu. At the same time, the plaintiffs’ statement expressed explicitly,

“If your corporation signs this Settlement Agreement with other Chinese forced labor victims or their descendants of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa worksite, then it should state clearly in the Settlement Agreement that the proposed “solution” for the forced laborers at the Shinanogawa worksite does not include us in terms of the number of victims to be paid and the amount of money involved, and also deduct the sum meant for us from the total amount of the so-called ‘atonement money’; otherwise we shall take it as a new violation of our legal rights and interests, and will hold your corporation accountable for such deed.“

Nevertheless, when Nishimatsu disclosed information about the “settlement” to the Japanese media on April 17, 2010, it continued to include the plaintiffs as part of its “settlement” arrangements.

As the agent of the Chinese plaintiffs, the author therefore issued a protest letter to Nishimatsu on April 19, 2010, but the corporation has not made any response. In the Settlement Agreement signed on April 26, 2010, Nishimatsu continued to include the plaintiffs who had already openly stated their rejection of this Settlement Agreement in its “settlement” arrangements. While Nishimatsu has yet to resolve its wartime forced labor issue, it violates de facto the human rights of the Chinese forced labor victims once again.

Chinese news coverage of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa settlement and its rejection by plaintiffs involved in the lengthy litigation. (CCTV video available) |

Nishimatsu has pushed aggressively this problematic “settlement” model, deliberately creating a false impression that the legacy issue of abducting and enslaving Chinese forced labor victims has achieved a “complete resolution”. The purpose is to buy out its legal liability for severe human rights violation with a small sum of money. Once some Chinese victims accept and sign on to such a “settlement”, despite the fact that these signatories do not have authorization from all other victims, Nishimatsu will regard “Chinese people’s right to claim had been waived” to be an established fact and a “complete resolution” of the issue to be achieved. This is the effect of such a “settlement” model. From a legal point of view, unless one is authorized, one has no authority to sign on behalf of others. However, this principle is violated in the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa “settlement” as the victims who have explicitly rejected the Settlement Agreement and those who have not yet been located are all involuntarily included in the binding provisions of this Settlement Agreement. Their claim issues are also unilaterally regarded as resolved within the “complete resolution”. Such a deed is in obvious violation of law and blatantly disrespects the human rights of these victims.

Nishimatsu dodges with ease its legal liability and historical responsibility of severe human rights violation by paying a petty sum of less than 50,000 Chinese Yuan Renminbi to each victim of the Shinanogawa worksite or their heirs. The Chinese victims’ side, on the other hand, pays a heavy price of losing the right to legal recourse henceforth as stipulated in Clause 6-1 of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement, that “… the victims’ side gives up all the rights to claim from the appellant (i.e. Nishimatsu) in Japan as well as in other countries and regions“.

4. The “relief (救濟)” in the Settlement Agreement is not relief under legal rights

The preamble of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement cites the 4/27 ruling of the Supreme Court of Japan. The Court ruled that Chinese people’s legal right to claim had been waived. The Court, at the same time, opined, “It is expected that the concerned parties, including the appellant (i.e. Nishimatsu), will make an effort to provide relief for the losses suffered by the victims in this case“.

According to the original text of the 4/27 ruling, the term “relief” mentioned in the verdict is obviously NOT implying relief in the judicial sense. In the legal domain, “judicial relief” refers to relief as the right of the litigant. For the term “relief (救濟)” outside the judicial domain, it refers to “helping people in want or living in a disaster area with money or materials“, according to the Modern Chinese Dictionary.

The 4/27 ruling of the Supreme Court of Japan already concluded clearly that legally the Chinese people had lost their right to claim, implying that they had thus also lost the right to judicial relief in court. Hence, the type of “relief”, as opined by the Court, from Nishimatsu and other concerned parties for the Chinese forced labor victims certainly does not refer to judicial relief. Thus, the meaning of the term “relief (救濟)” used in the Settlement Agreement can only be relief of a charitable nature.

5. “Atonement Money (償い金)” is not “Damages (賠償金)”

“Atonement money” (償い金) is not a legal term. In Japanese, the term is of daily usage with a broad connotation, having emotional hues and the meaning of repaying indebtedness.

“Damages” (賠償金) is a legal term with clear connotation, meaning to assume liability by making payment to the victim. This term in both Japanese kanji (賠償金) and traditional Chinese characters (賠償金) is identical and has essentially the same meaning.

In 1995, under pressure from different quarters, the government of Japan set up the Asian Women’s Fund to handle the issue of “comfort women” forced into sexual servitude by the Japanese military.

Based on the Japanese government’s position that the issue of “comfort women” was already resolved in the peace treaties made by Japan with the victims’ countries, the money paid to the victims should not be termed as damages or compensation. Hence, the term “consolation money (慰問金)” was used in the tentative plan released to the public through the media in August 1994. This term was repudiated by various stakeholders. In order to uphold its position of not assuming the liability, the Japanese government sought out another term, “atonement money (償い金)”, and used it to replace “consolation money”. Thereafter, the term “atonement money” appeared many times in the planning and promotion documents of the Asian Women’s Fund issued by the then-Chief Cabinet Secretary and other top politicians.

In the Asian Women’s Fund, the Japanese government ambiguously shifted its liability from paying damages to giving out “humanitarian” aid, including medical assistance, to the victims. Such a shift reflected the charitable relief hue of the Fund. The term “atonement money”, according to the goals of the Asian Women’s Fund, became the substitute term for “aid”, and was used frequently in the official documents of the Fund. It was exactly due to the insincerity of the Japanese government and its unwillingness to undertake liability that the Asian Women’s Fund was boycotted and criticized by the overwhelming majority of the victims and concerned organizations in Asia. At present, the Fund has concluded its payouts and related activities.

If Nishimatsu officials had the sincerity to make settlement, to offer apology and pay damages to the Chinese forced labor victims, why do they not use the term “damages (賠償金)” that has the same written characters in both Chinese and Japanese, and has the same and unambiguous connotation in the two languages?

The term “atonement money” in the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement echoes the purpose of citing the 4/27 ruling in the preamble of this Agreement. The purpose of insisting that the “Chinese people’s right to claim damages had been waived” is to shirk the legal liability. Hence, in provisions regarding payment to the Chinese victims, the Agreement vigorously avoided using the term “damages”, a proper legal term that implies undertaking liability.

Therefore, the term “atonement money (償い金)” viewed in the context of its intentional usage in the Asian Women’s Fund and in the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement is, without doubt, not “damages” as claimed by some supporters of this Settlement Agreement.

It is also worth mentioning that the legally valid version of the Settlement Agreement confirmed in the Tokyo Summary Court is the Japanese version, not the translated Chinese one. Therefore, in the Chinese version as provided by the Japanese lawyers, the term “atonement money (償い金)” being translated as “damages (賠償金)” is misleading to Chinese readers.

6. Subsequent obligations for those who have accepted the “settlement” and also for their agents

Clause 6-2 of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement stipulated that “the other party (i.e. the Chinese forced labor victims and their descendants) and their agents…., from now on have the responsibility, regardless of whether they have submitted the required document as mentioned in Clause 5-7, to ensure that the appellant (i.e. Nishimatsu) would not have any burden whenever anyone outside the other party makes a damage claim against the appellant.“

The implication of Clause 6-2 of the Settlement Agreement is that from now on, whenever anybody makes a damage claim against Nishimatsu regarding its enslavement of Chinese forced laborers (even though the person who makes the claim has not accepted this “settlement”), those who have accepted this “settlement” and their agents will have the responsibility to come forward to resolve this claim issue, making sure that Nishimatsu will not have any further burden. In plain language, Nishimatsu has paid out a small sum of money to enlist some helping hands.

In this provision (i.e. Clause 6-2), reference is made to Clause 5-7 which stipulates that the China Human Rights Development Foundation has the obligation to explain the purpose of this “settlement” to those who request payment of the “atonement money”. Clause 5-7 also states that the Chinese victims who accept the “atonement money” have to sign two copies of the document acknowledging the purpose of the “settlement”, and that one of the copies will be submitted to Nishimatsu by the China Human Development Foundation.

7. Different Legal Status of the Settlement Agreement and the Confirmation Items Document

Two documents arose from the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa “settlement”, the Settlement Agreement signed by both parties (i.e. the President of Nishimatsu and some non-plaintiff victims’ heirs) and the Confirmation Items document signed only by the lawyers of Nishimatsu and the Japanese lawyers, who were authorized to sign by the non-plaintiff victims and descendants – even as the five actual plaintiffs whom the Japanese lawyers had been representing refused to take part in the agreements. Similar arrangement was made in the case of the Nishimatsu-Yasuno “settlement” on October 23, 2009.

Why are there two documents arising from one “settlement”? An analysis of the status and the legal efficacy of the two documents is necessary.

Firstly, in terms of process and format, the Settlement Agreement was signed by Nishimatsu and some descendants of some victim laborers, and was also verified by the Tokyo Summary Court. The Confirmation Items, on the other hand, was signed only by the Japanese lawyers commissioned by the respective parties, but was not verified by the Tokyo Summary Court.

Hence, the Settlement Agreement is a judicial document and the Confirmation Items document is not.

Secondly, in terms of contents, the Confirmation Items list out the two parties’ opposite positions and their different understandings concerning some critical contents of the Settlement Agreement.

However, some parts of the statements made in the Confirmation Items, in fact, exceed the stipulated meaning of the concerned provisions in the Settlement Agreement. Moreover, in the Settlement Agreement that was verified by the Tokyo Summary Court, there is no mention about the status of the Confirmation Items document in this “settlement” nor even about its existence. Therefore, the legal efficacy of the Confirmation Items is highly questionable. Even if both parties may ratify afterwards what their Japanese lawyers have done regarding the Confirmation Items, since the Confirmation Items document was not verified in the court, its legal status is not comparable to the Settlement Agreement.

Obviously, in terms of format, the Settlement Agreement is in a superior position and the Confirmation Items document, which is in an inferior position, does not have the legal efficacy that supersedes the Settlement Agreement.

8. Conclusion

As agent of the Chinese plaintiffs, the author participated in many compensation lawsuits brought to the courts of Japan by victims of forced labor and “comfort women”. In the course of these litigations of more than ten years, having been in contact with hundreds of victims and learned from their painful stories, I feel strongly the evils of the war that caused extremely serious pain and suffering to the Chinese. Until now, the government of Japan and the concerned Japanese corporations have not yet undertaken their liability towards the victims. As an attorney, I feel obliged to help the victims to realize their fundamental desires for defending their dignity and human rights.

In the process of negotiation with Nishimatsu for almost a whole year, the Shinanogawa lawsuit plaintiffs made huge efforts in attempting to reach a sincere settlement while upholding their rightful position. Together with the author, they gave frank opinions, via their Japanese lawyers, on the proposed settlement terms to Nishimatsu. For example, in the draft of the Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement, Nishimatsu used similar wordings as in the Yasuno Settlement Agreement to acknowledge its “historical responsibility”. However, without putting this in the context of Nishimatsu’s acts of enslaving the victimized Chinese laborers, such acknowledgment becomes vague and empty.

With input from the plaintiffs and the author, Nishimatsu agreed to specify in Clause 1 of the Settlement Agreement the time when the violations occurred, i.e. “during World War II”, and to replace the term “labor” with “forced labor”. For another example, the plaintiffs and the author believed the name of the fund for settlement should reflect, to a certain extent, the gravity and liability of the serious human rights violations committed by Nishimatsu. However, Nishimatsu at first proposed to name it as “Peace and Friendship Fund”, the same name used in the Yasuno “settlement”. We did not agree to follow the Yasuno “settlement” in having the term “friendship” in the name of the fund. Instead, we proposed two options: (1) “Historical Responsibility Fund” or (2) “Peace Fund”. Eventually Nishimatsu accepted naming the fund as “Peace Fund”.

In the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement, there are words like “apology” and “deep and profound retrospection”. As Guan Jianqiang, Professor of International Law at East China University of Political Science and Law, pointed out in his March 2010 article, “Suggestions Made Before the Finalization of the Shinanogawa Settlement”:

“Although the apology of the Japanese corporation is stated in the Agreement, it lacks an explanation of why the Japanese corporation apologizes. In other words, without adding in the apology provision statements like: ‘the corporation enslaved the victims and obtained benefits from doing so…’, any apology made to the victims is really confusing in logic.”[6]

Around the time of the Nishimatsu Yasuno and Nishimatsu Shinanogawa Settlements, the supporters of those “settlements” pointed out that the surviving Chinese victims were getting senior in age and it would be of comfort to surviving victims if they could receive some monetary “compensation” while still alive.

However, the author feels these supporters are confused about a principle: that the violations perpetrated by the concerned Japanese corporations have caused serious and permanent harm to the bodies and minds of the victims. So unquestionably the perpetrators owe the responsibility to pay damages to the victims. Yet if their reasoning becomes that of only providing some monetary assistance for the victims, they can realize this simply by fund-raising from the public. So it is wrong to use such reasoning to give up the rightful demand for damages from the perpetrating corporations. Monetary assistance and fulfilling responsibility to pay damages are two approaches with two distinct and different implications. These two approaches should not be confused, otherwise the perpetrators can easily evade their liability.

Upon learning that the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa plaintiffs rejected publicly the insincere “settlement” agreement, concerned Chinese people, including overseas Chinese, are deeply touched. Despite their own not-so-well-off financial situations, these surviving victims or their heirs have stood their ground to defend human rights, their own dignity, and China’s national dignity. To show support and respect for these plaintiffs, some concerned Chinese individuals and groups came forward to offer financial assistance. Such act is a realization of the universal desire to uphold human rights, to offer mutual respect and support in a united struggle against injustice. This generous act of supporting struggle against injustice is by nature totally different from Nishimatsu’s offer of charitable relief, cloaked under the name of “atonement money”. Such generosity from the broader community also proves that it is not impossible to solicit public donations to financially assist the victims in their struggle to demand damages from the perpetrators.

There are those who feel the amount granted to each Nazi slave laborer under the German Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” is somewhat lower than what was offered by Nishimatsu’s settlement funds, so the fact that the former fund was praised while the latter was criticized appears to be unfair to the Japanese side.

The author would like to point out that the above opinion holders might have overlooked the legislations and the series of actions postwar Germany has been undertaking, which reflect Germany’s resolve to face history and to deal with its war responsibilities squarely. In these aspects, Germany is far ahead of Japan, as agreed by the international community. The primary concern in this Nishimatsu “settlement” is its premise-that Nishimatsu evades its liability and offers “atonement money” that is tinted with hues of charity. Thus the Nishimatsu “settlement” fund cannot be compared to the Remembrance, Responsibility and Future Foundation of Germany.

The Japanese lawyers representing the Chinese forced labor plaintiffs in nearly all the damage claim lawsuits suggested setting up a foundation for comprehensively settling all compensation issues regarding Chinese forced labor. As the Chinese lawyer involved in the Shinanogawa lawsuit and numerous other compensation lawsuits brought to the courts of Japan by victims of forced labor, the author and various plaintiffs supported this suggestion. So on November 5, 2008, 103 plaintiffs of Chinese forced labor lawsuits officially sent to the Japanese Government and concerned corporations the “Proposal on the Complete Resolution for the Issue of Abduction of Chinese People to Japan for Forced Labor during Wartime”.[7] The thrust of this proposal is to seek an out-of-court settlement and to set up a foundation to settle once and for all the issues around the severe human rights violations involved in the abduction of Chinese people to Japan for forced labor.

The author does not deny that out-of-court settlement is one of the means to resolve issues of wartime legacy. While this proposed settlement implies certain compromise, it does not sacrifice basic principle. Being the liable parties, the Japanese Government and the concerned corporations should face the historical facts squarely, undertake the liability, apologize to the Chinese victims, and pay compensation-this is the uncompromisable principle within a settlement.

Undoubtedly both the Japanese government and the concerned corporations should sincerely apologize and compensate the forced labor victims for the brutal mistreatment during their captivity. However, Nishimatsu only offered some money of charitable relief hue to the victims. This perfunctory and casual approach adopted by Nishimatsu to end its liabilities for such grave human rights violations is not acceptable because it totally contradicts the plaintiffs’ original objective in the damages claim.

Since the Nishimatsu “settlements” have so many problems, the Chinese forced labor victim plaintiffs in 13 compensation lawsuits in Japan assume the core member roles and have united with other non-plaintiff forced labor victims and their descendents to form the Federation of WWII Chinese Forced Laborers. The objective of the Federation is to defend the legal rights of the nearly 40,000 Chinese abducted to Japan for forced labor, and to steadfastly demand that Japan and the concerned corporations make sincere apology and compensations.

In addition, the International Labor Organization of the United Nations has repeatedly issued statements urging the Japanese government to offer apology and compensation to victims of its forced labor and military sexual slavery (“comfort women”) during wartime.

Since 2007, the United States of America, the Netherlands, Canada, the European Union, and some two dozen municipalities in Japan have passed resolutions urging Japan to apologize to and compensate the “comfort women” victims. Recently I learned that the State of California, while calling for tenders for its High Speed Railway construction, plans to include a provision that the companies tendering will be checked for its activities during WWII.

The above series of events prove that the international community has never given up its concern about the atrocities committed by Japan during WWII and Japan’s war crime responsibilities. Such atrocities and responsibilities will not be forgotten nor disappear with time: the only option for Japan is to sincerely apologize and compensate its victims.

Kang Jian is an attorney and Director of Beijing Fang Yuan Law Firm, member of the Constitutional Human Rights Committee of the All Chinese Lawyers Association (ACLA), member of the Disciplinary Committee of Beijing Lawyers Association, Deputy Director of the ACLA Steering Committee of Compensation Litigations Against Japan for WWII Chinese Victims, and Executive Director of the Investigation Committee on Atrocities Committed Against Former Chinese “Comfort Women”. As agent for former Chinese “comfort women” and forced laborers, Kang Jian participated in a total of 13 damage claim lawsuits against the Japanese government and Japanese corporations in the courts of Tokyo, Fukuoka, Niigata, Gunma, Kyoto, Sapporo, Yamagata and elsewhere since 1995. She can be contacted at [email protected].

William Underwood researches ongoing reparations movements for forced labor in wartime Japan. The author of numerous articles on the subject in The Asia-Pacific Journal, he wrote this introduction for The Journal. He is a coordinator for The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus and can be reached at [email protected]

This is the English translation of an updated version of Kang’s article originally written in Chinese. The updated article was prepared for The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. The English translation was provided by Thekla Lit, Co-chair of Canada ALPHA (Association for Learning and Preserving the History of WWII in Asia). She can be contacted at [email protected].

Recommended citation: Kang Jian, “Rejected by All Plaintiffs: Failure of the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa ‘Settlement’ with Chinese Forced Laborers in Wartime Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 32-5-10, August 9, 2010.

ENDNOTES

[1] This article is a revised version of my previous article entitled A “Settlement” Based on the Premise of the Right to Claim Being Waived – Comment on the Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa “Settlement” published in China Legal Daily and People’s Daily OnlinePeopl on May 18, 2010.

[2] For the Nishimatsu-Shinanagawa Settlement Agreement refer to Appendix A for the Japanese version and Appendix B for the translated Chinese version as provided by the Japanese lawyers representing the Chinese victims.

[3] Refer to Appendix E – Statement issued by Canada ALPHA on March 25, 2010.

[4] Besides Han Yinglin, the other 4 forced labor plaintiffs all passed away during the course of the litigation. Their descendants who inherited their legal status as plaintiffs were formally recognized by the Japan courts.

[5] For Confirmation Items refer to Appendix C for the Japanese version and Appendix D for the translated Chinese version as provided by the Japanese lawyers representing the Chinese victims.

[6] For Prof. Guan Jianqiang’s article refer to Appendix F.

[7] For the “Proposal on the Complete Resolution of the Issue of Abduction of the Chinese People to Japan for Forced Labor during Wartime” refer to Appendix G.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Nishimatsu-Shinanogawa Settlement Agreement

Appendix C: Confirmation Items document

Appendix D (Chinese): Confirmation Items document (translation as provided by Japanese legal team)

Appendix E: Statement issued by Canada ALPHA on March 25, 2010