[Ed. Note: Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.]

During the Battle of Okinawa, thousands of civilians were caught in the crossfire as U.S. and Japanese troops waged one of the final – and bloodiest – fights of World War Two. The combat lasted for more than three months, devastated the south and centre of the island and forced starving refugees to flee to the relative safety of the north. There, they turned to the place which had always sustained them during difficult times – the sea.

One of the areas whose seaweed, fish and shellfish provided relief for traumatized survivors was Cape Henoko. Located on the northeast shore of Okinawa, Henoko is still held special by many elderly Okinawans who remember the way its bounty supported them – and today, it remains one of the environmentally-richest areas in Japan. Home to mangrove forests, sea turtles and a large colony of endangered blue coral. In 2009, researchers from the World Wildlife Fund discovered 36 new species of crustaceans. For many people, what makes the place so unique is its population of endangered dugong – a relative of the Florida manatee and once revered as a mythical animal by Okinawans – whose tell-tale grazing trenches have been spotted throughout the area (here).

For decades, this abundance of nature has existed uneasily alongside a sprawling U.S. marine base, Camp Schwab. During the 1960s, the installation housed nuclear warheads and U.S. veterans claim that Agent Orange was stored there in large quantities; run-off from the defoliant has been blamed for wiping out the area’s seaweed farms (here).

Now, Henoko faces a threat even more serious than these weapons of mass destruction – the construction of a new US military base. If built, the installation will bury beneath concrete between 120 and 160 hectares of the bay – wiping out the dugongs’ pastures, destroying swaths of coral and disrupting the very currents which make the bay and the surrounding seas so alive. Just as harmful is the extinction of local fishing crews’ trade, the constant roar of low-flying aircraft and the 24-7 threat of accidents.

Although the Pentagon first spelled out plans for a new base in Henoko in the 1960s at the height of the Cold War (here), its most recent incarnation dates to the mid-1990s. Following the gang rape of an Okinawan school girl by U.S. service members, Tokyo and Washington attempted to placate Okinawans’ rage with a promise to shut the marine corps base in Futenma – the widely-feared installation in the urban heart of the island. But this closure would come at a price – before Futenma was returned to civilian usage, Washington demanded that a replacement facility be found. The Pentagon saw this as their chance finally to get the Henoko base it had been wanting for 40 years – a particularly sweet deal given the fact that the cost of its construction – currently estimated at $2 billion – would be entirely financed by Japanese tax-payers.

In preparation for the destruction of Henoko, the Japanese government began a survey of the area in April 2004. The response of Okinawans and their supporters was immediate (here). Over the next 18 months, 60,000 people – many of them old enough to recall firsthand how the bay’s bounty had saved them during World War Two – embarked upon a three-front campaign of civil disobedience. On the land, they lay down in front of bulldozers. When the government attempted to bypass them by heading out to sea, demonstrators took to canoes. Beneath the waves, some protesters donned scuba tanks and confronted government divers. Faced with such overwhelming opposition, in September 2005, the Japanese government backed down.

But it hadn’t given up.

Over the next years, both Tokyo and Washington persisted with the plan – holding Okinawa residents to ransom with a refusal to close dangerous Futenma until the new base had been built. Meanwhile, the Japanese government poured sweeteners into the island amounting to $3 billion a year – which did very little to dent poverty in Japan’s poorest prefecture.

Having completed its seriously-flawed environmental assessments (which unsurprisingly claim the environmental impact of decimating Henoko is minimal), now all Tokyo needs is one final legal requirement – the approval of Okinawa’s governor, Nakaima Hirokazu.

The 73-year old politician is in a difficult position.

Nakaima is a member of the Prime Minister’s ruling Liberal Democrat Party, but, with an eye to Okinawan voter sentiment, he has staunchly refused to support the Henoko base plan – making him a renegade and outcast in his own party. Tokyo has a variety of underhand techniques with which they can pressure him to sign – they might threaten to withhold funds set aside for Okinawa or even sue him as they did Masahide Ota, the former governor who refused to renew land leases for U.S. bases in 1996.

Public opposition to the Henoko Base is adamant – a 2012 newspaper poll found that 90% of Okinawa residents oppose the plan and the leaders of all 41 of the island’s municipalities are also against it (here).

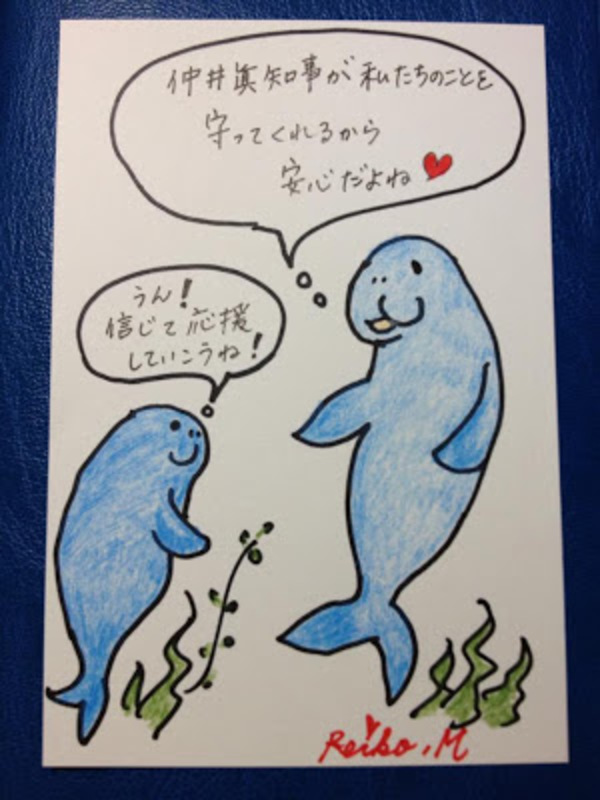

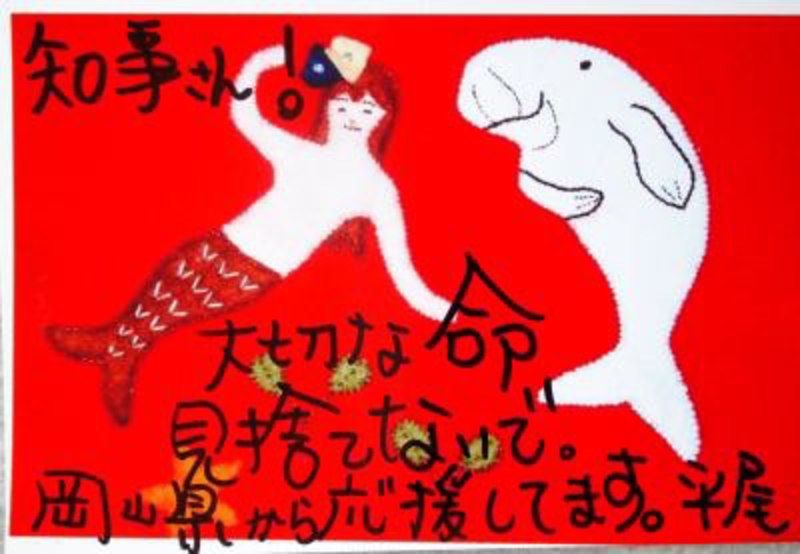

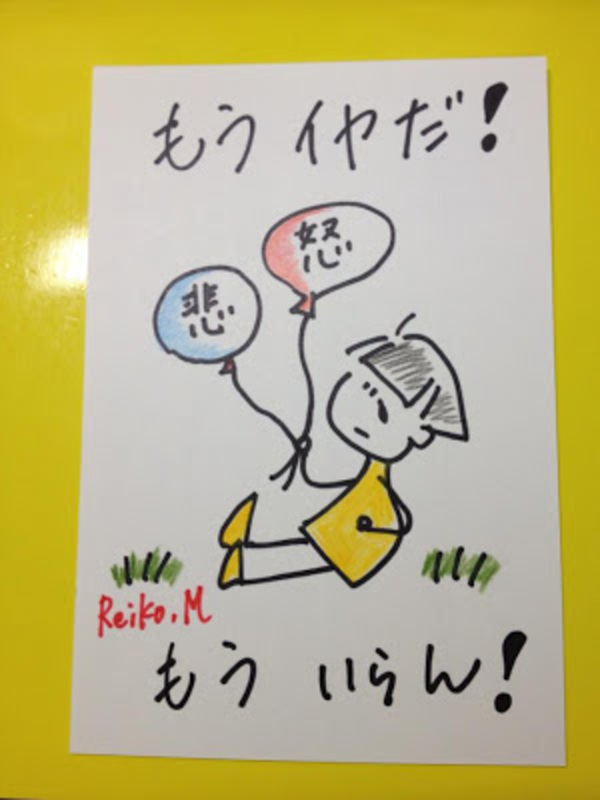

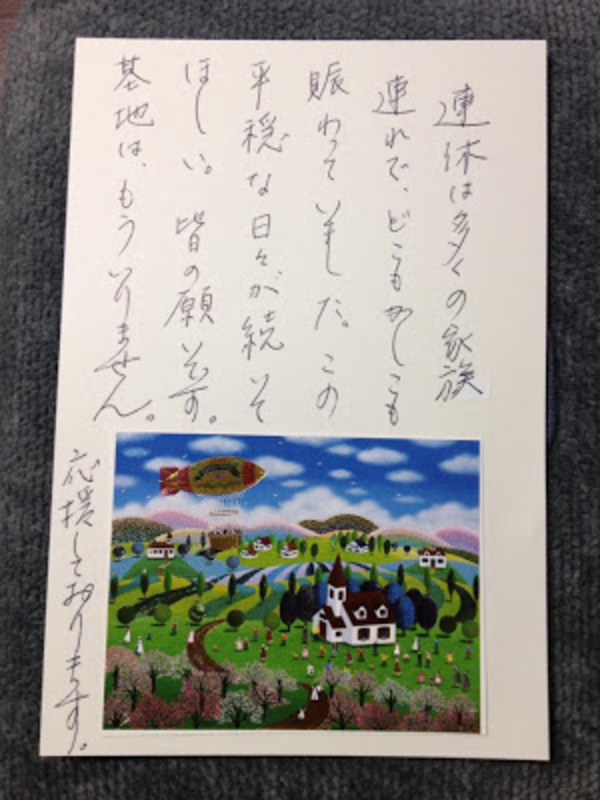

Out of this determination, a citizens’ movement has sprung up to fortify the will of the governor. Called the “Postcard campaign to save Henoko and Oura Bay,” hundreds of people from all over Japan and overseas have begun inundating the governor’s office with messages of solidarity.

Dr Masami Kawamura, the organizer of the campaign, says that its goal is simple. “We need to show the governor our support. We want him to stand firm and protect Oura Bay for future generations.”

School children have sent hand-drawn cards decorated with manga-cute dugong. Parents have sent pictures of their own children urging the governor to think about his legacy. Postcards have poured in from overseas.

The designs might be diverse but the message is united: Henoko is one of the world’s treasures and it needs to be protected – not buried beneath millions of tons of concrete.

Okinawa has already been destroyed by one war – and its residents know only too well that bases never protect civilians, they only make them more of a target.

These are dangerous days for the island. The governor – and the people of Okinawa – need all the support they can get.

Governor Nakaima Hirokazu

If you would like your postcard to be included on Dr Kawamura’s wall of support (here) please take a snapshot before posting and email it to: okinawaor[at]gmail.com.

Asia-Pacific Journal articles on related subjects include:

Gavan McCormack, Japan’s Client State (Zokkoku) Problem

Christopher T. Nelson, Dances of Memory, Dances of Oblivion: The Politics of Performance in Contemporary Okinawa

Gavan McCormack and Sakurai Kunitoshi, Okinawans Facing a Year of Trial: the Okinawa-Japan-US Relationship and the East China Sea