The Nuclear Family of Man

John O’Brian

The surprise film success in the United States in the summer of 2005 was March of the Penguins, a French-made nature documentary on the heroic mating habits of the emperor penguin in Antarctica. The American religious right endorsed the film with particular enthusiasm, celebrating the traditional family values demonstrated by the birds in their long, slow march from the sea to their breeding grounds and back again. Churches booked movie houses and organized visits for their congregations. Rich Lowry, editor of National Review, announced that the “Penguins are really an ideal example of monogamy,” and other neo-conservative commentators reflected on the penguins’ devoted child-rearing practices and penchant for familial sacrifice.[1] March of the Penguins became the second-highest grossing documentary ever made, eclipsed only by Fahrenheit 9/1l, a film that also has something to say about family values and sacrifice. For American audiences that cared to make the connection, the pro-nature fable and the anti-war exposé came together around conceptions of globalism and isolation, as well as of family and hardship.

Front cover, exhibition catalogue of The Family of Man, 1955

The intersecting politics of March of the Penguins and Fahrenheit 9/11 serve as a preface, in the form of a truncated morality tale, to the concerns of this essay. I want to revisit an exhibition of photographs, The Family of Man, under the themes of humanism – a matter of fierce critique by Roland Barthes in the mid-1950s – and nuclear violence. The overriding proposition of the exhibition, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955, was that people are the same the world over, regardless of differences in geography and culture. At its crudest, the exhibition proposed that indigenous peoples living in Hokkaido are no different than Upper East Side millionaires living in New York. Embedded within this theme of putative commonality was an anti-nuclear sub-theme. A quotation from Bertrand Russell was used as a wall text: “The best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with hydrogen bombs is quite likely to put an end to the human race.”[2]

As the curator of the exhibition, J. Edward Steichen stated that he wished to offer a strong statement of revulsion on nuclear war and violence. During World War II, he had been in charge of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit of the U.S. Navy in the Pacific.

Edward Steichen aboard the USS Lexington, 1943 (Photo by Victor Jorgensen)

He had also organized two patriotic exhibitions, Road to Victory (1942) and Power in the Pacific (1945), for the Museum of Modern Art, New York. On the face of it, he was an unlikely figure to raise the torch against war and nuclear violence.

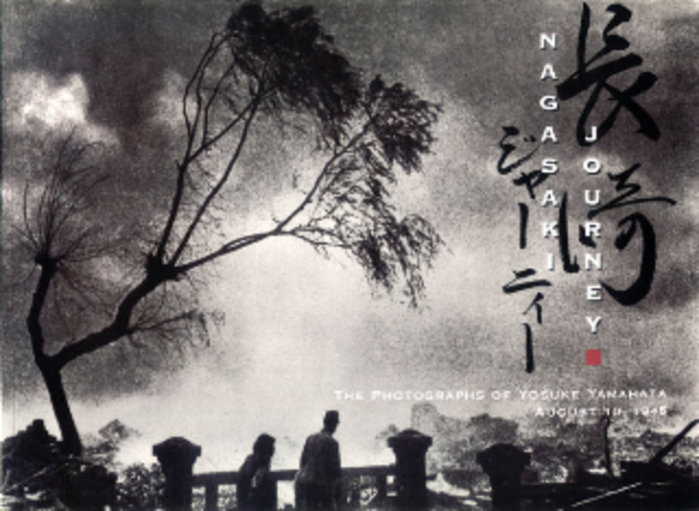

In 1952, Steichen visited Japan. A photograph shows him holding a book of photographs by Yamahata Yosuke, Atomized Nagasaki, in the presence of the photographer’s father.[3]

Yamahata Shogyoku, father of Yamahata Yosuke, with Edward Steichen in Tokyo, 1952

The strikingly unequal heights of the two men seem to point to the unequal power relations between the United States and Japan at the time. The photograph also raises questions about the intentions and outcome of the exhibition. Did The Family of Man make its audiences concentrate on the bomb, as Steichen hoped, thus recharging the global symbol of the mushroom cloud as something to be feared and combated? Or was the representation of nuclear threat subsumed in the exhibition by a rhetoric of global universality in a time of Cold War, thus allowing a photographic spectacle of love-making, birthing, child-rearing, food-gathering, playing, learning, aging and death to dominate? Was the threat of extermination a pivotal part of the narrative, so to speak, or did a phantasmagoria of marching penguins steal the show?

Front cover of Nagasaki Journey: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata, August 10, 1945

The answers are more complicated than they might initially seem. I will begin with some facts, which commentators on the show have often got wrong. (This is not because documentation on the exhibition is missing, but because it is so extensive and inconsistent.) The Family of Man opened at the Museum of Modern Art on January 24. I mention the precise date, as most do not, because it coincided with the first day of the Chinese New Year in 1955, which in turn coincided with mounting tension between the United States and China over the island of Formosa. With memories still fresh from the murderous nationalisms of World War II and the Korean War, the exhibition’s message of human commonality was attractive to audiences. The Family of Man quickly became so popular that “visitors came in crowds,” according to a reporter for the New York Times. “They lined up outside the museum, as at movie theaters, waiting for the doors to open.”[4] By the time the exhibition and its traveling offspring closed seven years later in 1962, it had been seen by more than nine million people in 61 countries around the globe.

Visitors to The Family of Man looking at a black and white image of an atomic explosion, Paris, 1956

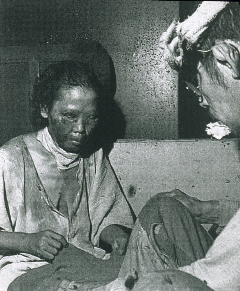

Under the auspices of the United States Information Agency the exhibition traveled the world, beginning its European tour in West Berlin and a second tour in Guatemala City. The logic of these two cities as the initial points of departure was dictated by Cold War diplomacy. Berlin was divided into competing Communist and Western sectors, and in Guatemala CIA-backed forces had recently overthrown the democratically elected pro-Communist government of Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán. Four different versions of the exhibition were produced for Japan alone. By the end of 1956 almost a million people in Japan had seen it, roughly 10% of the audience for the exhibition worldwide.[5] In deference to the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, a large black-and-white photographic image of a mushroom cloud included in other traveling versions of the exhibition was omitted. Instead, photographs taken by Yamahata in Nagasaki on the day following the explosion were substituted. These images showed, as the photographs in The Family of Man did not, the human toll and devastation caused by the bomb. Soon, however, they were censored as well. When the emperor visited The Family of Man in Tokyo, Yamahata’s photographs were curtained off and then removed altogether from the exhibition.

Yamahata Yosuke, untitled photograph taken in Nagasaki, 10 August 1945

The Family of Man was a benign cultural demonstration of American political values. From the point of view of cultural diplomacy it was a spectacular success, even traveling to Moscow in 1959. The exhibition formed part of the American National Exhibition in Sokol’niki Park, the site of the infamous Krushchev-Nixon kitchen debate, occupying its own building adjacent to pavilions housing displays of automobiles, refrigerators, model homes, stereo equipment, vacuum cleaners, color televisions, air conditioners, Pepsi-Cola and other commodities of capitalist prosperity provided by American corporations for the occasion.

Richard Nixon and Nikita Krushchev, who is holding a souvenir plastic bowl, American National Exhibition, 1959

As part of the bureaucracy charged with advancing American foreign policy, the role of the United States Information Agency was to help to undermine Communism, promote capitalism and spread democracy – and to do so quietly. “[W]here USIA output resembles the lurid style of communist propaganda,” a directive warned, “it must be unattributed.”[6] The United States had to appear to be going about its business softly. The Official Training Book for Guides at Sokol’niki Park makes no mention of Communism, capitalism or democracy and says only that the United States hopes to demonstrate “how America lives, works, learns, produces, consumes, and plays.”[7] This anodyne string of verbs parallels those used to describe, in press releases and news reports, the intentions of The Family of Man. The exhibition’s message of commonality meshed seamlessly with the global ambitions of American liberalism and multinational capital. People are everywhere the same, so the slogans of universality and corporate desire go, and every house must have a refrigerator. The photographer Tomatsu Shomei, a critic of both the Occupation and the accompanying rush towards Americanization, later commented: “The message is that everyone is happy – but is everyone really that happy?”[8]

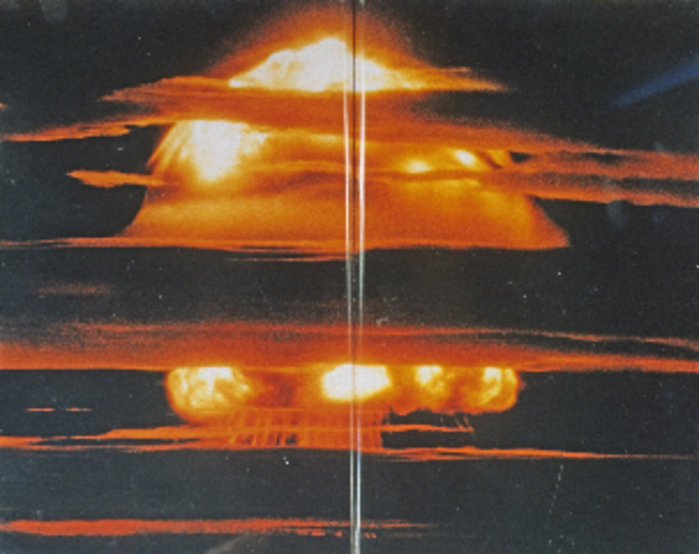

In one of the last rooms in the New York version of the show, viewers were presented with a six-by-eight foot color transparency of test Mike, a thermonuclear explosion from Operation Ivy at Enewetak Atoll, an image first published in Life magazine on May 3, 1954. The representation of the mushrooming orange and red fireball, partially obscured by dark clouds streaking horizontally across the glow of the blast and of the depicted plane, was the only color image in the show.

Detonation of test Mike, Operation Ivy, Enewetak Atoll, 31 October 1952

Visitors to The Family of Man standing in front of a color transparency of test Mike, New York, 1955

Minimal information was provided on the image in the exhibition or the catalogue, just its source and title, in keeping with the labels attached to the other photographs displayed in The Family of Man. Life magazine had not been much more forthcoming about the image. Beside an alliterative caption, “Fireball Boils Brightly,” the magazine had reported only that the photograph was taken with a dark filter fitted over the lens of the camera, and that the Federal Civil Defense Administration had just released it for circulation. What concerned the magazine was the “atomicity” of the bomb, by which I mean the structural force and the visual effects produced by processes of nuclear fission and fusion. As I define the word, atomicity places a premium on scientific nuclear discourse as opposed to discussion of the bomb’s realpolitik instrumentality as a weapon, its power to obliterate whole populations, to contaminate the natural world and to awe enemies. Life did not mention the Cold War build up in the arms race, for example, let alone the potential dangers of radioactive fallout over a radius extending beyond ground zero. This was more than two months after the Japanese tuna fishing boat, Lucky Dragon 5, sailing outside the officially demarcated danger zone, was sprayed with radioactive ash from thermonuclear test Bravo, detonated on Bikini Atoll on March 1, 1954. The entire crew suffered from radiation sickness, and the chief radio operator died eight months later.[9]

Daigo Fukuryū Maru (Lucky Dragon 5), the Japanese tuna fishing boat exposed to nuclear fallout from an American thermonuclear test

Instead, Life informed readers that, “As the [fireball] rises over the shock cloud, expanding gases from the fireball cool and freeze water vapor in the air, covering the mushroom with an icy shroud.” The description is elegant, even chilling – the concluding phrase, “covering the mushroom with an icy shroud,” is almost elegiac, an eschatological figuration of last rites – but it makes no direct reference to war, least of all to the human consequences of nuclear weapons. Fifteen years later Hannah Arendt published her book On Violence, in part because she perceived there had been a dissipation of the revulsion for violence that had followed World War II, as well as a dissipation of the non-violent philosophies that had arisen around the early Civil Rights movement. In 1954, Life reflected little of the revulsion ascribed to the period by Arendt.

A publicity notice released by the Museum of Modern Art shortly after the opening of The Family of Man stated that its purpose was to celebrate the sameness of human existence by means of the democratic language of photography. “Sameness” is what the following two images emphasize. In Eugene Smith’s photograph of two small children, a boy leads a girl out of darkness and into light, affirming the truism that children represent the hope for the future – and equally, of course, the prejudice that boys will naturally lead the way. In Carl Mydans’s photograph, three generations of a Japanese farming family pose in a field with their tools. In the exhibition, Mydans’s image was accompanied by several other photographs of families, taken in Italy, the United States and Bechuanaland. The series provided a reassuring representation of “the universal family of man.”

Eugene Smith, photograph included in The Family of Man exhibition, 1955

Carl Mydans, photograph included in The Family of Man exhibition, 1955

The aim of the 503 photographs selected for display by Steichen, who was head of photography at the museum, was to provide a positive message. “It is essential to keep in mind,” Steichen wrote, “the universal elements and aspects of human relations and experiences common to all mankind rather than situations that represented conditions exclusively related or peculiar to a race, an event, a time or place” (emphasis added).[10] One assumes that the list of excluded uncommon conditions extended to class relations. According to Wayne Miller, Steichen’s close associate in the navy’s photography unit during the war and principal assistant in organizing the show, six million photographs were reviewed for possible inclusion, some of which were solicited and others of which were drawn from published sources. The search was for photographs that conveyed collective emotions, representing humanity in the abstract; photographs of “situations,” to use Steichen’s word for historically contingent images, lacked the desired quality of transcendence and were rejected. As a photographer working in the Pacific at the conclusion of the war, Miller had visited Hiroshima in October 1945 and taken photographs of surviving victims. None of these photographs was included in The Family of Man. Instead, Miller exhibited a series of photographs of his wife and children.

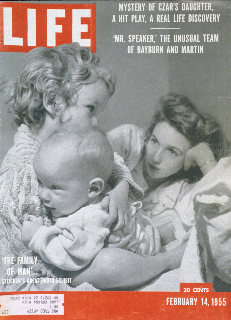

Wayne Miller, Cover of Life Magazine, 14 February 1955

Also excluded from the exhibition was the work of another American military photographer, Joe O’Donnell, a marine sergeant who photographed Hiroshima and Nagasaki as well as other bombed cities in Japan in 1945-46.[11]

Front cover of Japan 1945 by Joe O’Donnell

The Family of Man exhibition was greeted with wide critical approbation, both for the story it told as well as for how it told it. Although a few American commentators offered dissenting views – the photographer Walker Evans, for instance, whose work was not included in the show, wrote disdainfully of its “human familyhood [and] bogus heartfeeling”[12] – the vast majority agreed with Carl Sandburg, brother-in-law of Steichen and author of the prologue to the catalogue, that here was “A camera testament, a drama of the grand canyon of humanity, an epic.”

It was these same qualities in the exhibition that drew the attention of Roland Barthes, The Family of Man’s most frequently cited early commentator. After seeing the exhibition in Paris in 1956, he declared it to be a product of “classic humanism,” a collection of photographs in which everyone lives and “dies everywhere in the same way.” “[T]o reproduce death or birth tells us, literally, nothing,” he wrote acerbically. The show suppressed “the determining weight of History” (Barthes’s capitalization), and thereby succumbed to sentimentality.[13] Barthes dismissed what he considered to be the exhibition’s repetitive banalities and its moralizing representation of world cultures, a view he correctly observed to have been drawn from American picture magazines. In fact, a sizeable part of the exhibition was chosen from back issues of Life and Look at a time when Europe, to say nothing of Japan, was being heavily subjected to the forces of Americanization.

Six months after the opening of The Family of Man, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy, was lynched in Mississippi for whistling at a white woman. The photographs of Till’s open coffin and mutilated face after he was pulled from the Tallahatchie River received international media coverage and was an early impetus for the American Civil Rights movement. In his article for Paris Match, Barthes referred specifically to the lynching. “[W]hy not ask the parents of Emmett Till, the young Negro assassinated by Whites what they think about The Great Family of Man?” There was no place in the exhibition, Barthes implied, for historically specific photographs like those taken of Till at his open-coffin funeral.

Emmett Till in his Coffin, Chicago, 1 September 1955

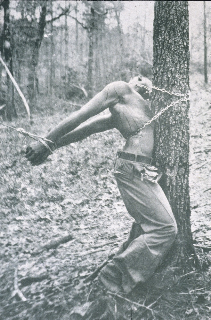

Barthes was more right than he knew about this, for a photograph of an earlier lynching had initially been included in the exhibition only to be removed after the New York opening. Taken by an anonymous photographer in Mississippi in 1937, it represented the death slump of a black man chained to a tree, his bound arms pulled taut behind him.[14]

Death Slump at Mississippi Lynching (1937), photograph removed from The Family of Man exhibition shortly after its opening in New York, 1955

In preparing the exhibition, there seems to have been a compelling rationale for Steichen to incorporate the photograph of the lynching. Along with the artist and photographer Ben Shahn, one of whose Farm Security Administration images was included, Steichen had been a member of a UNESCO committee established “to study the problem of how the Visual Arts can contribute to the dissemination of information on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” One of the recommendations of the committee was to mount an exhibition on civil rights, and it is likely that Steichen wished to reflect in his own exhibition something of the visual reach of that socially conscious aim. The plan backfired, at least from Steichen’s point of view. By including and then withdrawing the controversial image, he became responsible for raising a socially contentious issue only to suppress it. “There are dead men, but no murderers” in the exhibition, the critic Phoebe Lou Adams caustically observed, and with the removal of the 1937 lynching photograph there was also one corpse less.[15] Wayne Miller downplayed the excision. Steichen, he said, “felt that this violent picture might become a focal point [in the reception of The Family of Man] . . . [It] provided a form of dissonance to the theme, so we removed it for that purpose.”[16] In other words, the photograph was extirpated so that the overriding harmonies of the exhibition, constructed to appear seamless, would not fall apart.

But the harmonies of the exhibition may still have fallen apart, if not for a majority of viewers then for some. Notwithstanding the removal of the lynching image, its presence (or, rather, its absence) must have stayed in the memory of some of those who had seen it. But exactly how this photograph of atrocity would have remained in the minds of those who had seen the exhibition, or of those who had read press accounts of its removal, is not straightforward. It cannot be assumed, for example, that all spectators saw it as a provocation for social change and justice. Susan Sontag observes in her book Regarding the Pain of Others that viewers of photographs of suffering – she is speaking generally here and not specifically about the victims of lynching or of nuclear holocaust, as seen in Domon Ken’s extraordinary photograph in which laughter trumps suffering – are no more likely to occupy the same subject positions than are viewers of any other kind of image.

Domon Ken, Mr. and Mrs. Kotani, from the Hiroshima series, 1957

Some may have experienced the violence depicted, others may be opposed to the violence but have not experienced it, and yet others may themselves have been responsible for inflicting the type of pain represented in the image. Audience responses to representations of suffering are not uniform, and the same images can be read variously as memorializations of loss, as denunciations of perpetrators, as exhortations to inflict more pain, as calls for peace, as cries for revenge.

The photograph of the lynching in The Family of Man is no exception. Spectators are differentiated by time, place and social background in responding to an image of a black man who was chained to a tree and killed. Whether they might also agree that those responsible for the lynching should be brought to justice, or that such events should never occur, or that human life is nasty-short-and-brutish, or that the photograph should be banned and its reproduction prohibited, inevitably depends on the sensibilities and background of the viewers as well as on their responses to the dominant narrative of the exhibition. A photograph, and specifically the excised lynching photograph, is capable of supporting any of the short declarations just offered.

The photograph of the lynching did not appear in the exhibition catalogue. Nor did the color image of the nuclear explosion. Even the black-and-white photograph of an atomic blast that was substituted for the original color photograph in traveling versions of the show that followed the New York venue (with the exception of those versions sent to Japan, as mentioned earlier), which was first published in Life magazine, was excluded from the catalogue. The reasons for the substitution and for the shift from color to black-and-white are unclear to me. Steichen seems not to have discussed them publicly, and private correspondence and documents in various archives provide no leads. He did, however, talk about his conception of the exhibition’s anti-nuclear message. In a film on the exhibition produced by the United States Information Agency for international circulation in 1955, Steichen emphasized that he wished viewers to read the photograph of the atomic blast and nine nearby photographs of distressed human faces in tandem.

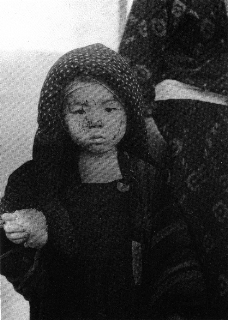

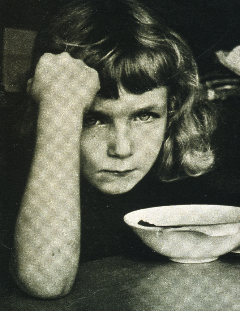

Yamahata, Nagasaki Japan, 10 August 1945

Joan Miller, one of the group of nine faces exhibited in The Family of Man, 1955

In the center of the group of nine faces was a photograph taken by Yamahata on August 10, 1945, representing an injured child holding a rice ball and identified in the catalogue simply as Nagasaki Japan. Steichen had probably first seen the photograph, along with others by Yamahata, during his 1952 visit to Japan; Yamahata’s 1952 book, Atomized Nagasaki, used the photograph for the cover. Joan Miller’s image of a sullen girl leaning on her elbow was installed immediately to the left of Yamahata’s injured child. Steichen imagined, so he said in the film, that the nine faces were “thinking of the horrible, multiplying factor, the incredible multiplying factor of the atomic weapon. Will this be? Must this be?”[17] It is not entirely clear what Steichen meant by this brief reference to “the horrible, multiplying factor” of the bomb. He may have been thinking of the multiplying production of nuclear weapons as well as of the dangers posed by the accelerating arms race. Less plausibly, he could have been referring to the effects of radiation and the genetic damage passed down from generation to generation.

There is no direct way of ascertaining how visitors to the exhibition responded to Steichen’s intended anti-nuclear message, or whether they empathized with the distressed faces in terms of the threat, any more than there is a way of determining how visitors responded to the lynching photograph or to knowledge of its removal. But there are persuasive historical reasons to think that the concussive impact Steichen wished to impart was not realized. How could a piece of minor theater, argued one of the dissenters at the time, a bomb room containing an explosion that “looks like any other splash of orange fire,” do the job?[18] In the single photograph of a thermonuclear explosion, it seems, Steichen hoped to represent the insanity of technological hubris and to decry the U.S.-Soviet arms race that was producing ever-deadlier nuclear armaments. He was looking for the trick card that was so high and wild he would not have to deal another, to paraphrase some lines from Leonard Cohen’s The Stranger.

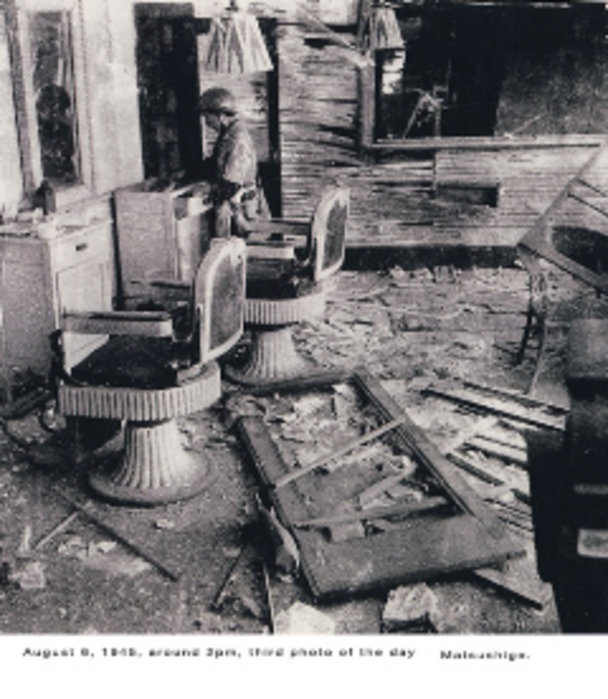

Matsushige Yoshito, Hiroshima (Third Photograph), 6 August 1945

In my judgment, Steichen did not find the card: the overwhelmingly affirmative thrust of the exhibition smothered whatever potential may have existed for the representation of nuclear tragedy. His decision to represent the destructive power of the bomb in the form of a mushroom cloud and a single photograph by Yamahata, while rejecting other images of the destruction of human life and cities that occurred beneath the mushroom cloud, such as those of Hiroshima by Matsushige Yoshito, corresponded to the propaganda policies of the United States following August 6, 1945. The effects of radiation were consistently denied by official US sources. When a Tokyo news service reported that, “Many of those who received burns cannot survive the wounds because of the uncanny effects which the atom bomb produces on the body,” and that, “Even those who received minor burns, and looked quite healthy at first, weakened after a few days,” the Pentagon was quick to respond.[19] It accused Tokyo itself of promulgating propaganda. The Japanese wished “to capitalize on the horror of the atomic bombing in an effort to win sympathy from their conquerors,” a spokesperson stated. Given that the overriding theme of the exhibition was the glory of mankind, and that photographs “peculiar to a race, an event, a time or place,” including those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the aftermath of the bombings, were programmatically banished, Steichen could never have transcended the ahistorical humanism he was offering to near universal applause. He was still a military man, after all, as well as a curator and photographer. In deference to his rank during World War II, Steichen liked to be addressed at the Museum of Modern Art as “Captain.”

Notes

[1] Rich Lowry quoted by David Smith, “Film about the family life of penguins inspires America’s religious right,” Guardian Weekly, 23-29 September 2005.

[2] Bertrand Russell, quoted in The Family of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art and Maco Magazine Corporation, 1955), 179.

[3] For a publication on Yamahata’s Nagasaki photographs in English that also includes a translation of the photographer’s original introduction, see Nagasaki Journey: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata, August 10, 1945, edited by Rupert Jenkins (San Francisco: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995).

[4] Jacob Dischin, “Family’s Last Day: 270,000 Have Visited Steichen Exhibition,” New York Times, 8 May 1955.

[5] Edward J. Steichen Archives: Family of Man, Museum of Modern Art, New York, VII 145.1. The most thorough account of the exhibition is by Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995). Another useful book is The Family of Man: 1955-2001, edited by Jean Back and Viktoria Schmidt-Linsenhoff (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 2004).

[6] Quoted from the archival records of the United States Information Agency by Walter L. Hixson, Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture and the Cold War, 1945-1961 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 194.

[7] Official Training Book for Guides at the American National Exposition in Moscow, edited by Dorothy E.L. Tuttle (Washington, D.C.: United States Information Agency, 1959), 12.

[8] Tomatsu Shomei quoted by Sandra S. Phillips, “Currents in Photography in Postwar Japan,” in Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of the Nation, edited by Leo Rubenfien, Sandra S. Phillips, and John W. Dower (San Francisco Museum of Art, 2004), 51.

[9] The incident sparked a national campaign in Japan to ban nuclear weapons. Twenty million signatures were collected in support of the national and international anti-nuclear movement. See Nakagawa Masami, Honda Masakazu, Hirako Yoshinori and Sadamatsu Shinjiro, “Bikini: 50 Years of Nuclear Exposure,” Asahi Shimbun, January 26, 27, 28, 2004, translated for Japan Focus by Kyoko Selden.

[10] Publicity notice, “Museum of Modern Art Plans International Photography Exhibition,” 31 January 1955, Steichen Archives, Museum of Modern Art.

[11] Joe O’Donnell, Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine’s Photographs from Ground Zero (Nashville: University of Vanderbilt Press, 2005).

[12] Walker Evans, “Robert Frank,” US Camera 1958 (New York: US Camera Publishing Corporation, 1957), 90.

[13] Roland Barthes, “The Great Family of Man,” Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers (St Albans, Hertfordshire: Picador, 1976), 100-102.

[14] The source of the photograph was not identified in The Family of Man exhibition or catalogue.

[15] Phoebe Lou Adams, “Through a Lens Darkly,” Atlantic 195, April 1955, 69.

[16] Wayne Miller interviewed by Sandeen, cited in Picturing an Exhibition, 50.

[17] Steichen speaking in The Family of Man, a 26 minute-film produced by the United States Information Agency in 1955. The agency made more than 300 prints of the film, and circulated them in both 16 mm and 35 mm.

[18] Adams, “Through a Lens Darkly,” 72.

[19] Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell, Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial (New York: G.P. Putnam’s, 1995), 41.

This essay is a revised and expanded version of an invited lecture at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, Hiroshima City University, delivered on December 6, 2007. I wish to thank Robert A. Jacobs, Steven L. Leeper, Kazumi Mizumoto, Hiroko Takahashi for their comments on the presentation. At the time of the lecture, I was a visiting professor at Ritsumeikan University, Kyoto, investigating nuclear photography.

John O’Brian is Professor of Art History and Brenda & David McLean Chair at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver. His books include: Beyond Wilderness; Ruthless Hedonism; and Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism. His current research is on the engagement of photography with the atomic era. Posted at Japan Focus on July 11, 2008.