Politics in Command: The “International” Investigation into the Sinking of the Cheonan and the Risk of a New Korean War

John McGlynn

Introduction

On May 20, South Korea’s defense ministry made public a short statement on the “international” investigation into the sinking of the South Korean warship, the Cheonan, on March 26, which left 46 sailors dead. U.S. South Korean officials, along with major western news organizations, have been describing this statement as a “report,” but since a) the authors of the document describe it as a “statement,” b) the document’s contents consist of several pages of description of physical evidence (visual aid supplements relating to the evidence are not included in the document but have been made available separately by South Korea’s defense ministry) along with unverifiable assertions and conclusions, and c) only the 5-page document rather than a rumored 400-page version has been made public, “statement” seems a more accurate description than “report” and will be used in this article.

The Cheonan went down near the Northern Line Limit (NLL), the disputed western maritime extension of the Demilitarized Zone that divides North and South Korea. The statement on this incident, officially titled “Investigation Result on the Sinking of ROKS ‘Cheonan’,” was produced by an investigative team called “The Joint Civilian-Military Group” (Hereafter, “JIG” is used to describe the JIG statement, document, team and investigation). It presented the conclusion that the Cheonan was sunk by a torpedo fired by a North Korean submarine.

The English version of the JIG statement is five pages long (see the complete text below). Thus far, only the 5-page version has been made available to western media. A more detailed 400-page investigative document is said to exist (language[s] unknown). Outside the governments whose representatives participated in the investigation, this longer document has apparently been circulated to China and perhaps other governments, but seems unavailable not only to the general public and the press, but even to lawmakers in South Korea.

Though unremarked in the western media, the 5-page statement actually consists of two statements. The first statement reviews engineering and other physical evidence that allegedly explain how the Cheonan sank. The information in this review, which may be plausible, is not discussed in this paper. Five countries contributed to the work described in the first statement: the United States, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Australia and Sweden. How and how much they contributed is unknown. In any event, the full 5-page statement appears to be the exclusive property of the South Korean defense ministry, since the ministry controlled its release on May 20 and since then has handled official presentations.

|

Photo: A Crane lifts the stern of the Cheonan |

The second statement, one page in length, presents a conclusion that North Korea sank the Cheonan by torpedo. The authorship of this second statement is not made clear. The statement itself only says that the U.S, South Korea, the U.K, Canada and Australia, but not Sweden, contributed to the second-statement findings. Moreover, the second statement describes these five countries as members of a unit called the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force. How this Task Force relates to the JIG investigation is unclear (more on this point below).

What is certain, however, is that based on casualties suffered the five countries are among the six main belligerent nations (Turkey rounds out the six) that fought against North Korea in the 1950-1953 Korean War. South Korea, the country’s defense ministry reports, recently hosted a gathering of officers from the five countries to discuss “joint military capabilities to secure airspace on the Korean Peninsula.” More than 60 years after the 1953 armistice, the five countries continue to cooperate in assessing their own joint military capabilities and those of North Korea in the event of a new conflict on the Korean Peninsula.

A White House press release has described the JIG investigative document as the work of “a team of international investigators” who provided “an objective and scientific review of the evidence.” U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton added that it was “a thorough and comprehensive scientific examination, and the United States and other international observers were deeply engaged.” In making these statements, U.S. officials have so far failed to explain which document they have in mind, the publicly available 5-page version or the rumored 400-page version.

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, in a May 24 address to the South Korean nation, talked about an investigative document based on “a thorough and objective scientific investigation” by an “international joint investigation group. “With the release of the final report,” he said, “no responsible country in the international community will be able to deny the fact that the Cheonan was sunk by North Korea.”

|

Photo: South Korean President Lee Myung-bak |

Major western news organizations described “a report from international investigators” of an attack on the Cheonan (May 20 Financial Times), “an international investigation [that] has found overwhelming evidence” (Washington Post), and “an investigation by international experts” (May 30 BBC News). Some news accounts carried the comment by Yoon Duk-yong, South Korean co-leader of the investigative team, that “there is no other plausible explanation” (this is also the final line of the report): a North Korean submarine torpedoed and sunk the Cheonan.

Immediately after the 5-page statement’s release Hillary Clinton intoned “provocative actions have consequences” and “the international community” “cannot allow [North Korea’s] attack on South Korea to go unanswered.”

|

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton |

In contrast to these descriptions of the JIG document as a solid body of evidence produced by a respectable group of international experts, the analysis below will show that the 5-page statement, particularly the section that blames North Korea for attacking and sinking the Cheonan, which was produced by a group of states that were belligerents against North Korea during the Korean War and could be again if a new conflict erupts, contains inherent political bias. As a result, claims of an impartial and objective investigation should not be accepted at face value but subjected to scrutiny.

As for the claim that the 5-page statement represents the collective work of a team of international experts or at least includes expert foreign input, the most crucial aspect of that claim, North Korea’s responsibility for the Cheonan’s sinking, has been contradicted by a key U.S. representative on the JIG team, as is documented below.

This paper is more about a misleadingly described or reported and politically tainted investigative process than about the credibility of evidentiary findings. Nevertheless, one of those findings is examined because of its centrality to the JIG claims: the Hangul marking allegedly written by North Korea on one of several torpedo parts dredged up by a trawler five days before the 5-page statement was made public.

An “international,” “objective” and “scientific” investigation?

While the South Korean and US governments seek to cloak the JIG’s 5-page document with the legitimacy of an international investigation, this is an unsigned South Korean statement that draws on anonymous expert opinion from the US, UK, Australia, Canada and Sweden. There are five reasons why the 5-page statement cannot be considered scientific and objective, nor does it meet the test of being international in the sense that a single government has not controlled or strongly influenced the statement’s contents.

First, the second statement inside the 5-page document that attributes responsibility for the sinking is international only in this sense: it incorporates intelligence gathered by five of the countries that fought against North Korea during the Korean War (1950-1953): the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and South Korea. As such, it is patently a weapon in the ongoing US-Korean War for which there has been an armistice but no peace treaty.

The opening paragraphs of the 5-page statement reads:

The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (JIG) conducted its investigation with 25 experts from 10 top Korean expert agencies, 22 military experts, 3 experts recommended by the National Assembly, and 24 foreign experts constituting 4 support teams from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sweden. The JIG is composed of four teams–Scientific Investigation Team, Explosive Analysis Team, Ship Structure Management Team, and Intelligence Analysis Team.

In our statement today, we will provide the results attained by Korean and foreign experts through an investigation and validation process undertaken with a scientific and objective approach.

However, the section of the 5-page statement that blames North Korea for the Cheonan sinking suggests that Sweden did not endorse this conclusion, and in absenting itself, required that a new group be constituted.

The second statement opens with:

The findings of the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force, comprised of 5 states including the US, Australia, Canada and the UK and operating since May 4th, are as follows:

The MCITF presents five findings. The fourth is the most critical, as this is the only finding that puts forth a claim of direct evidence tying a North Korea torpedo to the sinking of the Cheonan. It states:

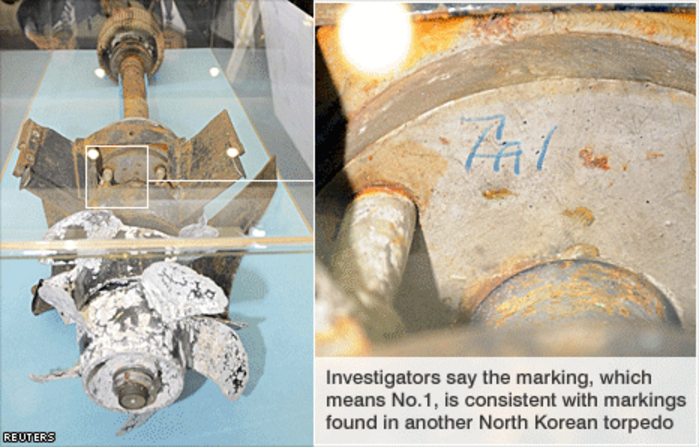

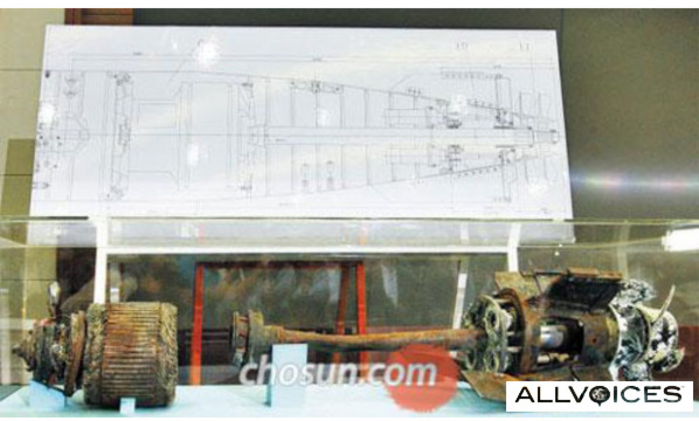

The torpedo parts recovered at the site of the explosion by a dredging ship on May 15th [five days before the 5-page statement was issued], which include the 5×5 bladed contra-rotating propellers, propulsion motor and a steering section, perfectly match the schematics of the CHT-02D torpedo included in introductory brochures provided to foreign countries by North Korea for export purposes. The markings in Hangul, which reads “1번(or No. 1 in English)”, found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo. Russian and Chinese torpedoes are marked in their respective languages.

The function of the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force (hereafter, the MCITF) and its relationship to the rest of the JIG team is unclear in the following critical respects:

1. Does the MCITF equate to the Intelligence Analysis Team, which would seem to make it part of the JIG, or was it formally or functionally separate from the JIG investigation even though its findings were included in the JIG statement? The MCITF and Intelligence Analysis Team are each only mentioned once. Whether they are the same, different or related cannot be determined from reading the JIG statement.

2. If formally part of the JIG, did Sweden, described in the media as the most neutral member of the JIG team, accept the MCITF’s fourth finding, or any of its findings? If the MCITF was not formally a part of JIG, did Sweden have any say over the inclusion of its findings in the JIG statement?

The separate mention and unknown workings of the MCITF make clear that the 5-page JIG statement is actually two statements in one. Moreover, the second statement indicates that the MCITF has been “operating since May 4th.” Thus a question arises: Why did the MCITF’s formation come so late, since the Cheonan investigation started in early April, and why did it come at all? Was it necessary to constitute the MCITF because of Sweden’s dissent from a crucial conclusion of JIG?

Interestingly, one day before the 5-page statement was released, CBS News reported that “only Sweden, which also sent investigators, is a reluctant partner in blaming the North Koreans.” While this report is suggestive, the western media appears not to have asked Sweden for clarification.

As noted, the U.S., South Korea, the U.K., Canada and Australia comprise the MCITF. Just as all five countries fought against North Korea during the Korean War, all participate at some joint level in assessments of North Korea’s military fighting power. As one example of their coordination, South Korea’s defense ministry news website reported on May 25 that intelligence and operations officers from the five countries “held their annual joint Korea Tactics Analysis Team meeting” as they have been doing since 1993 for four days starting on May 17. One officer in attendance provided this anonymous quote: “Through the meeting, we were able to check and reinforce joint military capabilities to secure airspace on the Korean Peninsula.” While hardly a difficult task (absent Chinese intervention), since North Korea’s air strength is practically non-existent and its pilots have trouble finding fuel for practice, the comment is indicative of the nature of the group’s ongoing activities.

There are strong reasons to doubt the MCITF’s finding of North Korean responsibility for the loss of the Cheonan. One of these reasons concerns the Hangul marking, a matter discussed in the box below.

In the meantime, new findings about the sinking may come in the near future. Russia currently has a 4-member team with expertise in torpedoes and submarines in South Korea to conduct its own investigation, results of which may be known later in June. China may follow with its own inquiry (South Korea has invited China to investigate, but as of June 1 Beijing had reportedly not replied).[1] Also, if presented with the Cheonan incident by the South Korean government, the United Nations Security Council may order the establishment of a fact-finding mission.

Even if no prima facie reason exists to reject the five-country finding, until new investigative results are produced the finding will remain tainted by a lack of objectivity and political bias. The same would be true in analogous circumstances. For example, the U.S. and its western allies would surely reject prima facie a finding of culpability by an investigative team created by Iran and, along with Iran, consisting of Pakistan, Syria, Libya and Lebanon (countries that have faced U.S. political and military pressure at various times over the last 30 years) that had looked into an alleged U.S. attack on an Iranian naval vessel.

|

Photo: South Korean navy personnel stand guard next to the wreckage of the naval vessel Cheonan |

Second, it is meaningless to call the JIG investigative team “international” when the JIG statement itself and media accounts make clear that the management of the statement’s production and its public release have been under the control of the South Korean military, with some coaching from the U.S. For the same reason, it is probably wrong to suggest, as Army Lt. Gen. Park Jung-yi, the South Korean military chief and co-chair of the JIG team, did, that it operated by “consensus.”

An apparently more accurate description of the JIG team did manage to slip into some newspaper accounts, such as this in the June 4 Wall Street Journal: “After the [Cheonan] was recovered, a South Korean-led international investigation team on May 20 announced it was destroyed by a torpedo of North Korean origin.”2

The first page of the statement explains that the JIG team included “24 foreign experts constituting 4 support teams from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sweden.” A supporting role suggests an absence of decision-making power. Perhaps that was not the case here, but in the absence of any indication of the JIG team’s methodology or any information about the authors’ identities and professional backgrounds, this is a plausible assumption.

As for the “consensus” asserted by JIG co-chair Lt. Gen. Park, did the foreign experts participate in shaping that consensus or merely support conclusions reached by the South Korean side? U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that “the United States and other international observers were deeply engaged,” a statement that is doubly revealing because it says nothing about participation by “foreign experts” in the writing or editorial approval of the statement. The word “observers”, moreover, suggests the experts were on the sidelines when investigative conclusions were reached.

The significant control exercised by the South Korean military over the JIG statement was made clear in the JoongAng Daily, which in a May 21 article on the statement’s release mentioned several South Korean military officials who had key oversight roles in the investigation.

Those officials were:

1. Army Lt. Gen. Park Jung-yi, the military co-chair of the JIG investigation

2. Air Force Brig. Gen. Hwang Won-dong, head of the Intelligence Analysis Team

3. Army Brig. Gen. Yun Jong-seong, head of the Scientific Investigation Team.

As noted earlier, the JIG team also included the Explosive Analysis Team and Ship Structure Management Team, team leaders unknown.

The other co-chair of the JIG team was Yoon Duk-yong, professor emeritus at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, who, according to one press account, has “a PhD in applied physics from Harvard University and was chosen as a top scientist by the Roh Moo-hyun administration” (the South Korean presidential administration before the current administration of Lee Myung-bak).

|

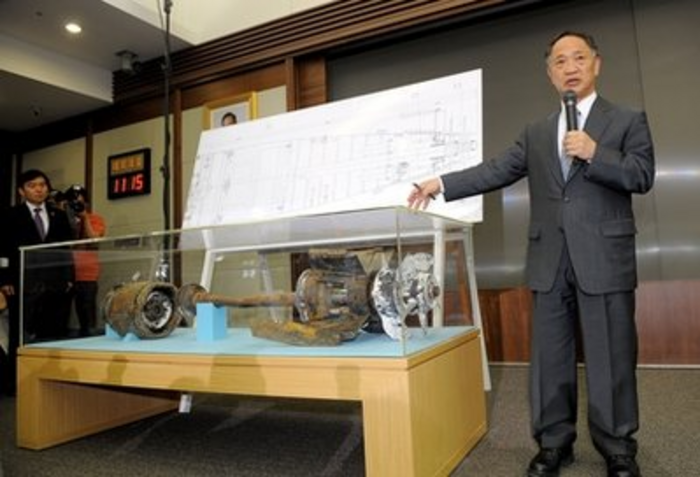

Yoon Duk-yong (right) presents the evidence |

Yoon was appointed JIG team co-chair on April 11 by South Korea’s defense ministry. As an eminent academic and as co-chair of the JIG team, Yoon’s participation obviously lends support to the claim that the JIG investigative team was partly civilian. For this reason, some attempt should be made to scrutinize his role in an investigation otherwise dominated by South Korean military officials.

In a June 2 interview with the Chosun Ilbo Yoon discussed the professional scientific approach he took toward the Cheonan investigation. “A scientist is aware of the fact that his research papers will be presented to the world and will be archived for generations to come,” he said. “That is how I felt as I pursued the investigation into the Cheonan.”

Apparently with his fellow South Koreans mainly in mind, a note of exasperation crept in when Yoon talked about critics of the JIG team’s investigative results. “In one sense, persistent denials of the evidence have nothing to do with science but are actually a matter of attitude toward the quest for truth. You need to be humble when searching for the truth,” he said. Though not directly quoted, the Chosun reports that Yoon believes “the country needs to foster a rational way of thinking among people through science education from an early age. Returning to direct quotes, “mad cow disease and even nuclear war are all issues that need a scientific way of thinking,” he said.

The interview provides interesting insight into Yoon’s professional outlook but it also reveals a degree of contempt for dissent and toward those without a scientific education (leaving them with an inability to grasp, for example, the scientific virtues of nuclear war).

Moreover, if “humble” is the watchword in the scientific quest, presumably this means things like patience, careful checking, transparency, a willingness to address valid criticism and so on. One has to wonder how much scientific humility was applied in the analysis of the torpedo parts that were found only five days before the JIG statement was scheduled for release, the only evidence made public by the JIG team to prove a direct link between the sinking of the Cheonan and North Korea. While the parts find itself was fortuitous, even more fortuitous was the handwritten “beon 1” (No.1) mark on one of the parts, said to resemble the Hangul script used in North Korea and written in ink that remained highly legible (even though corrosion and pitting surrounded the marking; see photos below) despite more than six weeks of submersion in seawater.

Several views of the Hangul marking on the torpedo part [See box discussion below]

Image A: Reuters photo in a May 21, 2010 BBC story.

Image B: May 20, 2010 Korea Times photo

Image C: May 21, 2010 JoongAng Daily photo.

Photo: South Korea’s Defense Ministry displays the motor and running gear of the torpedo alleged to have hit the Cheonan.

|

The Hangul marking on the torpedo propulsion section

There are many important issues raised in the JIG’s 5-page statement, a number of which have already been examined, judging by Internet writings, both by experts and by people posing reasonable questions. The second section of the 5-page JIG document is a 1-page statement that purports to demonstrate North Korean responsibility for the sinking of the Cheonan. As argued in this paper, this 1-page statement was probably produced by the South Korea government and then rubber stamped by five of the six countries represented on the JIG (the U.S., U.K, South Korea, Canada and Australia, but not Sweden). The remainder of this box discussion presents an examination of the evidence cited in the JIG statement as offering direct proof of North Korean responsibility. This is the Hangul marking on one of the torpedo parts recovered on the morning of May 15 from the Yellow Sea by a private South Korean trawler conducting dredging operations, five days before the JIG team’s investigative conclusions were made public. There are two ways the 5-page JIG statement discusses the Hangul marking. The first section of the statement comments as follows: “The marking in Hangul, which reads ‘1번(or No. 1 in English)’, found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo. The above evidence allowed the JIG to confirm that the recovered parts were made in North Korea” (underline added). The second section (1 page in length) of the JIG statement contains this comment: “The markings in Hangul, which reads “1번(or No. 1 in English)”, found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo. Russian and Chinese torpedoes are marked in their respective languages.” This section concludes with: Based on all such relevant facts and classified analysis, we have reached the clear conclusion that ROKS “Cheonan” was sunk as the result of an external underwater explosion caused by a torpedo made in North Korea. The evidence points overwhelmingly to the conclusion that the torpedo was fired by a North Korean submarine. There is no other plausible explanation. It is this second section that explicitly blames North Korea for the torpedoing and sinking of the Cheonan. Needless to say, the finding of a torpedo part with the Hangul marking five days before South Korea’s self-declared deadline to release the JIG statement was fortuitous for those South Korean government officials eager to finger North Korea. Without the marking, South Korea would have no visible direct evidence of North Korean culpability. Other visible evidence allegedly exists. The 1-page statement mentions that the recovered torpedo parts “perfectly match” schematics of a torpedo North Korea supposedly “included in introductory brochures provided to foreign countries by North Korea for export purposes,” but that claim is impossible to verify because no brochure copies have been made available for independent examination. And apparently won’t be, because according to a May 21 CNN report, “General Han Won-dong, director of South Korea’s Defense Intelligence Agency, declined to state [at the May 20 press conference hosted by South Korea’s defense ministry to release the 5-page JIG statement] how or where South Korea had obtained the brochure, citing security sensitivities.” As shown in the above views of the Hangul marking, the marking is handwritten, not inscribed or imprinted on the metal. It is perfectly legible, despite submersion in sea water for more than six weeks. Conveniently, the marking is in a place that can be easily photographed by the media and was written on a section of metal that appears to have undergone almost no pitting or corrosion. The photos show corrosion and pitting in all directions around the marking, but little on the metal surface that is marked. In Images A and C, the rusting at the base of the metal rod to the right (in Image C) of the marking appears to have two straight edges roughly at a right angle, as if someone cleaned the surface of rust. In fact, the approximately 1/3 of the round metal plate that can be seen in Image C seems to have a partially cleaned-up (perhaps metal brushed?) appearance. In Image B, the lower right corner of the square opening shows apparently broken metal. Whether it’s the corner of the opening itself or a piece of metal attached to the rod is unclear. Did natural underwater corrosion cause the break or was it the stress of the torpedo explosion or the jostling about in rough waters? If the former, it would seem that metallurgical testing could determine how long this torpedo debris was submerged. The 5-page statement contains no metallurgical information or data. Armscontrolwonk.org, a prominent US-based WMD and arms control website, publicized the availability of visual aids that accompany the 5-page statement. Apparently the visual aids were distributed at the May 20 press conference, but these too provide no metallurgical descriptions, nor, for that matter, any views of the Hangul marking. At a May 25 presentation to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Han Duk-soo, South Korea’s ambassador to the U.S., asserted [http://csis.org/event/senior-policy-group-discussion-rok-ambassador-han-duk-soo] that “the level of corrosion of the evidence was identical to that of the bow and stern of the Cheonan.” Again, no corroborating information or data was provided. At its KCNA website (English language), North Korea has repeatedly stated that the Hangul marking and other evidence is fraudulent.

|

According to the Chosun, during the interview Yoon “refuted rumors being posted on the Internet that the number handwritten on a piece of the torpedo retrieved from the bottom of the West Sea, which directly links North Korea to the sinking, could have been added by the South Korean military.” Though the JIG statement presents the marking as a critical piece of evidence and though some skeptics have presented grounds for arguing that it was faked, the Chosun did not provide Yoon’s refutation.

A more troubling interpretation is that Yoon intends “humble” to mean no one should question the authority of scientists or the conclusions of Yoon and his military JIG co-chair and other senior South Korean JIG colleagues, who collectively came together to write at the end of the JIG statement, “there is no other plausible explanation.”

As for Yoon and the JIG 5-page statement itself, nothing in the statement describes his contribution to the investigation, to the writing, or to supervising the statement’s production. So while as “a scientist” Yoon “is aware of the fact that his research papers will be presented to the world and will be archived for generations to come,” it would be helpful if the JIG co-chair were to describe his own contributions and those of his colleagues in preparing the JIG statement for presentation to the world. Even more helpful would be providing access to the 400-page version and answering questions about the contents of that larger document, not to mention access to surviving crew members and captain of the Cheonan, who other than one or two controlled news conferences seem to have been placed off limits to the press and the public.

One additional question goes to the issue of scientific integrity and independence of judgment: given the dominant role of the South Korean military in the investigation, how much room did Yoon have to exercise free scientific inquiry and reach conclusions unhampered by military considerations or the political/foreign policy goals of the Lee administration? As reported by the JoongAng Daily on April 12, Yoon’s appointment as JIG co-chair was announced by South Korea’s defense ministry. Neither the ministry’s news release section of its English-language website nor the JIG statement provides any information about the scope of authority or freedom of scientific inquiry granted to Yoon.

Nor is anything known about the mandate handed to Yoon and his military co-chair, Army Lt. Gen. Park. As discussed below, it is instructive to compare this lack of a mandate with one that was given to the fact-finding mission that produced the Goldstone report, another international investigation of recent fame.

Finally, perhaps the most hard-hitting yet succinct criticism of the JIG investigative process and statement is this excerpt from a May 28, 2010 editorial in the Hankyoreh which offers another perpective on the findings:

The [South Korean] administration maintained exclusive control over information during the investigation process. Then, without completing necessary steps for the report, the administration announced its findings in time for the beginning of the formal regional election campaign. The fact that the investigation was led by the very military leadership who would be subject to reprimand created its own credibility issues. As of now, almost none of the related data has been disclosed.3

Third, a brief comment by a key U.S. member of the JIG team who was present at the May 20 South Korean defense ministry press conference held to release the 5-page statement provides strong proof that South Korea, not an international team, produced the finding of North Korean responsibility for the torpedo sinking of the Cheonan.

According to a partial transcript and video of the May 20 press conference available on Arirang, a South Korean news website, U.S. Navy Admiral Thomas Eccles, described by Arirang as the “US representative on the Cheonan Investigation Team” (Eccles, like other JIG team members, is not identified in the 5-page report), provided this reply when asked in English the following question: “I was wondering what the other nations’ representatives’ specific roles in terms of investigation, and how do you analyze the final assessment.”

|

Rear Admiral Thomas Eccles |

Eccles: “The international team in close cooperation with the Republic of Korea Joint investigative group worked both in a collaborative way, very closely together, and also employing our separate tools and methods so we were able, before the torpedo debris was found, to analyze the evidence with experts, eyewitness and calculated and analytical methods, in all of those, we found an agreement, both within the Republic of Korea and all of the international team.”

If this comment is accurate, Eccles is saying the international team, including the U.S. representatives, did not work with the torpedo evidence. Rather, they completed their investigation before the torpedo debris was found. The second section of the 5-page document describing North Korean responsibility for the Cheonan’s sinking rests heavily on the torpedo evidence. Since the international team did not have access to the torpedo debris, we can only conjecture on the basis for its findings. In the end, it seems the international team merely rubber stamped a South Korean conclusion of North Korean guilt. But since Sweden was not one of the rubber stamping countries, possibly because it dissented from the guilty finding, the MCITF may have been contrived to bypass Swedish objections and at the same time preserve an aura of international impartiality.

Eccles conveys the impression that South Korea was in charge of the final phase of the JIG investigation. That final phase includes the discovery of the torpedo parts, the analysis of those parts (which includes the alleged North Korean Hangul marking) and, presumably, the write-up of the second section of the 5-page statement that charges North Korea with responsibility for the Cheonan’s sinking.

That this comment by Eccles seems to have gone unnoticed by major western media is remarkable. In just a few words, Eccles, an admiral and a decorated naval officer highly experienced in submarine technology and design (as stated in a 2008 US Navy biography), upends the JIG’s central “international” finding that North Korea sank the Cheonan. The Arirang video shows representatives from western news agencies among a large number of reporters attending the May 20 press conference. But it seems that none of the western reporters tried to question members of the international team, who, along with Eccles, were present at the press conference. If they did try, those attempts were not noted in their news accounts.

An excerpt from a May 20 BBC report illustrates the non-reporting not only of Eccles’ important comments but also of the views of any international team members: “The investigation itself was given an added air of impartiality by the presence of 24 foreign experts from America, Australia, Britain and Sweden. They are all said to support the conclusions reached.”

Strangely, directly questioning the international members of the international team about their international findings did not occur or was generally off limits.

Eccles’ comments were not universally ignored by the western media. But if reported, the report was at best partial. The significance of the fact that there was no international participation in the finding that tied North Korea to the retrieved torpedo parts was ignored or overlooked. One representative account comes from CNN:

“We worked closely and collaboratively, using separate tools and methods,” said Adm. Thomas Eccles of the U.S. Navy, adding that all members of the international team were in agreement.

Fourth, South Korean military and police officials have begun to crack down on the civil liberties of those expressing skepticism and distrust of the JIG statement. This leaves the South Korean military virtually alone in presenting a continuous stream of comment on the JIG statement. In addition, the Lee administration began to punish North Korea before the results of the Cheonan investigation were made public. All three actions betray a lack of confidence in the ability of the findings in the JIG statement to withstand public scrutiny.

The troubling actions by South Korean officials to suppress critical commentary belie confidence in the “scientific,” “objective” and “no other plausible explanation” findings of the JIG team. The Financial Times wrote on May 31 that “South Korea is battling to stem public doubts that North Korea sank one of its warships in March through a mixture of police investigations, public education and Twitter.” As part of the battle, Seoul police plan to charge four people with “spreading ‘false information'” and have put 11 others under investigation. Moreover, the police are examining “text messages” that are critical of President Lee and Internet users are being tracked “for signs that North Korea is using agents to spread dissent and possibly arrange terrorist attacks.” In other words, questioning the findings in the statement is to risk charges of being a North Korean agent.

Seoul prosecutors told the Financial Times that “the highest-profile figure under investigation, facing charges of defamation from the navy, is Shin Sang-chul, who was appointed to the investigative committee on the sinking by the opposition but was removed before its conclusion.”

|

Photo: Shin Sang-cheol |

Shin seems to have professional experience that qualifies him to participate in the JIG investigation. According to the JoongAng Daily, Shin “studied oceanography at Korea Maritime University and was commissioned as a Navy second lieutenant. He was discharged from active duty as a first lieutenant after serving on a patrol boat in the Yellow Sea. Following his military service, he worked seven years for shipbuilders.” Shin himself states in influent English that he has “built 3 bulk carriers of 136,000 tons and 10 container ships of 2,000-4,000 teu[*] in charge of hull structure, shipping machinery and outfittings, paint and nautical equipments including navigation system.” [TEU= Twenty-foot equivalent unit, a measure used for capacity in container transportation.]

In 2004 Shin’s professional life took a new turn. He began working for a “progressive Internet political magazine” called Seoprise. The JoongAng reports that the South Korean navy, angered by his writings on the Cheonan, “filed a petition on May 18 asking prosecutors to launch a probe, claiming that Shin had defamed the Navy by spreading false information.”

Instead of the sinking-by-torpedo conclusion in the JIG statement, Shin believes the Cheonan ran aground and then sustained some kind of blow (not caused by an explosion) before sinking. Evidence in support of that belief was put into a 27-page letter.

Shin sent to Hillary Clinton. In short, the JIG dealt with dissent within its own ranks by purging the offender one week prior to issuing its statement.

The JoongAng also reports that a prosecutor’s office has begun “a probe into Park Sun-won, former President Roh Moo-hyun’s secretary for national security, on charges that he spread false information about the sinking. Park, a Northeast Asia energy and security visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, who served as an adviser for a Democratic Party committee on the Cheonan investigation, said in an MBC radio interview in April that the Lee Myung-bak administration was concealing information about the sinking.”

Based on other news accounts in the South Korean press, Bloomberg reported on May 29 that South Korean Prime Minister Chung Un Chan “ordered the government to find a way to stop groundless rumors spreading on the Cheonan’s sinking, the JoongAng Daily said yesterday. Prosecutors questioned a former member of the panel that probed the incident over his critical comments, the paper said. The Joint Chiefs of Staff sued a lawmaker for defamation after she said video footage of the ship splitting apart existed, a claim the military denies, Yonhap News reported.”

Along with attempts to suppress discussion and crush dissent, South Korea’s defense ministry continues to have top military officials make public statements about the Cheonan investigation, rather than invite civilian officials or any of the anonymous “foreign experts” who were part of the Cheonan message to speak.

On June 1 two military members of the JIG team, Army Lt. Gen. Park Jung-yi and Army Brig. Gen. Yun Jong-seong, were presented by the defense ministry to the public. The ministry website explains that the purpose of their appearance was to rebut “suspicions that have been spread online” that come into conflict with “the conclusion of the probe into the sinking of the South Korean warship Cheonan.” In an apparent attempt to invest his remarks with military gravitas, the website noted that Brig. Gen. Yun appeared “in battle dress uniform.”

At one point during the Park and Yun presentations the Hangul No. 1 marking on one of the torpedo parts was raised (by which of the two military officials is not made clear). On this point the defense ministry website states the following:

“In regards to a speculation that North Korea does not mark “1 beon” using an Arabic numeral and a Korean letter that means “number,” the investigation team said that North Korean defectors testified the North uses “beon” mostly in signifying an order in a sequence.”

Park and Yun made their statements on the same day the interview with Professor Yoon appeared in the Chosun Ilbo. Given Yoon’s stated concern with the “quest for truth” and the ability of the South Korean people to engage in rational analysis, one has to wonder what he thinks about the use of unnamed defectors, some of whom no doubt depend on financial assistance from the South Korean government for survival, to provide the supposedly clinching evidence of North Korean culpability.

Fifth, no matter how much scientific and professional integrity Yoon or anyone else on the JIG team has, there are indications that the results of the investigation into the Cheonan sinking were either pre-determined or at least subjected to blatant political pressure.

The conclusion of the JIG investigation that has triggered a dangerous sequence of escalating rhetoric and military threats between North Korea and South Korea (fully backed by announcements flowing from the U.S. State Department and the Pentagon) was probably fixed on May 4, 16 days prior to the release of the JIG statement and 11 days before the only alleged piece of direct evidence of North Korean culpability was dredged up from the Yellow Sea, when during a national address South Korean President Lee said:

What is clear as of now is the fact that the sinking of the Cheonan was not simply an accident. As soon as I received the first report, I knew by intuition that it would escalate into a grave international issue involving inter-Korean relations. I instructed the Government to determine the cause of the sinking with international cooperation. Comprising top specialists, the international joint investigation team will be able to shed light on the cause before long. As soon as the cause is identified, the Korean Government will announce the findings to all countries of the world. After that, I will take clear and stern measures to hold anyone responsible accountable.

In short, presidential intuition found North Korea guilty of the Cheonan sinking. From there it was the job of the JIG team, perhaps under the full control of the South Korean military, to produce a finding that buttressed that intuition. And to make sure the finding could be characterized as “international” and supposedly free of South Korean bias, the U.S., U.K., Canada and Australia, all Korean War belligerents of North Korea and all participants in joint military conferences on future war-fighting scenarios, were brought in to endorse that part of the JIG statement (in the process pushing Sweden aside) that asserted North Korean culpability.

Comparison of the JIG Cheonan Statement with the Goldstone Report

A comparison of the 5-page JIG document with another investigative document of international renown, the Goldstone report, is instructive. Such a comparison illustrates how much the work of the JIG investigative team, including information about team members, their contributions to the investigation and investigative methodology, has been hidden from public view. To be sure, the unknown information may be contained in the 400-page JIG report supposedly in limited international circulation.4

The Goldstone report was produced by the UN Fact-Finding Mission, which was led by Justice Richard Goldstone, a prominent international jurist appointed by the president of the UN Human Rights Council. There were three other appointed members: a professor of International Law at the London School of Economics and a member of the 2008 fact-finding mission to Beit Hanoun; an advocate of the Supreme Court of Pakistan and former Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on the situation of human rights defenders, who was a member of the 2004 International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur; and a former Officer in Ireland’s Defence Forces and member of the Board of Directors of the Institute for International Criminal Investigations.

The report presented conclusions of an investigation into the December 2008/January 2009 Gaza conflict, in which more than 1,300 Palestinians and 10 Israelis were killed during the course of the Israeli invasion. The report contained evidence indicating serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by Israel during the Gaza conflict. It concluded that Israel’s actions probably amounted to war crimes, and possibly crimes against humanity. The report also found evidence of war crimes and possibly crimes against humanity by the Palestinians, but on a much smaller scale.

The findings of the Goldstone report were accepted by the United Nations General Assembly. However, the report has been condemned by Hillary Clinton and the U.S. Congress, along with the government of Israel.

The Goldstone report, 574 pages in length, contains the following elements, all fully explained and publicly available:

— methodology of the investigation

— context for the investigation

— the mandate handed down by the President of the United Nations Human Rights Council (“to investigate all violations of international human rights law and international humanitarian law that might have been committed at any time in the context of the military operations that were conducted in Gaza during the period from 27 December 2008 and 18 January 2009, whether before, during or after.”)

— the names of the fact-finding mission members and brief biographies

— how the fact-finding mission interpreted its mandate

— the dates and locations of meetings of the fact-finding mission and public meetings

— calls for submission of information

— attempts to cooperate with Israel (which ended in failure)

— the cooperation received from the Palestinian Authority and the Permanent Observer Mission of Palestine to the United Nations

— various difficulties encountered during the course of fact-finding mission’s investigation

By comparison, nothing remotely similar to these elements can be found in the 5-page JIG statement.

In regard to a mandate, this is especially important, because it establishes the contours of the investigation and influences what will and will not be investigated.

For all the reasons discussed above, it can only be assumed that the JIG team’s mandate was decided by the South Korean government or military, possibly with input from the U.S. The strongest support for this assumption from the JIG statement itself is the limited description in the opening statement of the JIG team structure,”24 foreign experts constituting 4 support teams from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sweden,” in which “support” is the key word.

Unilateral Reunification, Pre-emption, Cheonan and China and the Risk of War

South Korea, according to its defense minister, is now seeking the “strongest resolution” at the UN Security Council to punish North Korea for the Cheonan sinking. US and South Korean officials repeatedly stress that the two countries will work closely at the UN on this endeavor.

Before South Korea approached the UN Security Council, the U.S. had already proclaimed that it was leading a “united front” that includes South Korea and Japan. The three countries have been campaigning to internationalize the Cheonan incident. The goal is to force acceptance of the conclusion that the world needs to punish North Korea, whether through action by the UN Security Council or by handing the assignment to an Asian coalition of the willing, with US participation.

Before holding a June 5 trilateral meeting with Japanese defense minister Kitazawa Toshimi and South Korean defense minister Kim Tae-young on the sidelines of the “Shangri-La Dialogue” Asia security in Singapore, U.S. defense secretary Robert Gates made this statement:

“Attacks like that on the Cheonan undermine the peace and stability of not just the Korean peninsula, but the region as a whole,” he said. “To do nothing would set the wrong precedent. The international community can and must hold North Korea accountable. The United States will continue to work with the Republic of Korea, Japan and our other partners to figure out the best way to do just that.”

In his own statement, Kitazawa said that he wanted the summit to “serve as a strong message to the international community as well as to North Korea” and expressed the “hope that the three countries will be able to show our strong determination.”

China, which has Security Council veto power and is North Korea’s main benefactor, is key to winning UN approval for punishment. Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao has talked about judging the Cheonan incident in an “objective and fair manner” and based on the facts. The US and South Korea have dropped strong hints that the 5-page JIG statement is compelling and China does not need to wait. Both want China to act “responsibly.”

|

Photo: Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, left, met with South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, right, and Japan’s Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama, unseen, on Jeju Island on May 29 & 30. At a joint press briefing Wen said: “What is most urgent for now is to reduce the tensions from the Cheonan incident and especially avoid a clash.” |

On its own, South Korea has several times delivered the message of responsibility to China, most recently at the Singapore security summit. Interviewed by Yonhap, South Korean defense minister Kim described a meeting he had with Ma Xiaotian, deputy chief of staff of China’s People’s Liberation Army, during the summit: “I explained to him fully for over 30 minutes what caused the Cheonan incident, what surfaced in the process of the investigation,” he said. “China remains cautious, but we hope that it will reach a responsible conclusion.”

On June 1, Yu Myung-hwan, South Korea’s foreign minister, reportedly talked with the BBC about ways of choking off North Korea’s economic life . The minister’s actual words were “If cash inflow into North Korea is restricted, I think it will lower the possibility of nuclear weapons development and deter belligerent behavior,” but talk of sanctions or increased economic isolation rarely considers the damaging implications for the people of North Korea.

If cut off from the global cash system, North Korea and its population of 23 million could experience enormous economic suffering (unless rescued by China). Without cash (North Korea’s access to credit is virtually non-existent), importing and exporting would become almost impossible, resulting in total economic isolation. The effect of such a situation on the life of the nation is imaginable by referring to the 10-year oil embargo on Iraq during the 1990s, which had devastating consequences (as measured by various UN and NGO surveys) for the health and everyday survival capabilities of Iraqi society, with children found to be particularly vulnerable.

A cash cut-off would come atop a dense legal thicket of international restrictions on trade and commerce, well summarized by Michael Yo in the Asia-Pacific Journal, that already makes North Korea perhaps the most economically blockaded country in the world. This matrix consists of residual Cold War-era unilateral U.S. anti-economic and business development policies, U.S. extraterritorial law that forces companies in Europe, Asia and elsewhere to choose between doing business in North Korea or in the far more profitable U.S. market, and U.S. pressure on international lending institutions to deny financial and economic development aid to North Korea.

Regime change in Pyongyang is also open to discussion. In his May 24 special address on the Cheonan incident to the South Korean nation, President Lee Myung-bak called North Korea the “most belligerent regime in the world” and spoke of the need for that “regime to change” for the good of “the regime itself and its people.” Echoes of the justifications for the March 2003 US/UK-led invasion of Iraq are unmistakable.

Lee continues to promote a “Grand Bargain,” in which North Korea would surrender its nuclear weapons program in exchange for economic assistance and security assurances. North Korea has so far rejected the offer, probably because U.S. policies of economic punishment and military/nuclear threats are not factored in.5

To apply even more pressure on North Korea, South Korea’s military has raised the possibility of pre-emptive attack. Using rough English, South Korea’s defense ministry website reported that on May 18, Lee Sang-woo, the head of a national security review commission established on May 9 to review South Korea’s defense capabilities in light of the Cheonan sinking, discussed with commission members South Korea’s “need to shift its defense policy from defense disposition to deterrence posture.” Lee “added that it is important to be equipped with defensive capabilities that could completely neutralize the enemy’s intention to attack, but if Seoul takes action in advance, Pyongyang would not have made provocations in the first place.” In Lee’s view, two considerations compel a pre-emptive (“deterrence” is the term Lee uses) posture. “First is that the South’s military must develop and maintain military capabilities to make necessary decisive blow toward the enemy in peacetime. Another one is that Seoul needs to have firm will to use such capabilities if necessary.” Under a switch to a pre-emption posture, the best method for destroying key targets in North Korea, Lee said, is “aviation and naval power.”

In North Korea, the threat of pre-emptive aerial attack is likely to be regarded as a provocative and cruel reminder of the “unknown war,” Korean historian Bruce Cumings’ term for the Korean War, one largely forgotten in the West but certainly not in Korea. As Cumings wrote in 2004, “What was indelible about it was the extraordinary destructiveness of the United States’ air campaigns against North Korea, from the widespread and continuous use of firebombing (mainly with napalm), to threats to use nuclear and chemical weapons, and the destruction of huge North Korean dams in the final stages of the war. Yet this episode is mostly unknown even to historians, let alone to the average citizen, and it has never been mentioned during the past decade of media analysis of the North Korean nuclear problem.”

A few days after the remarks by Lee Sang-woo, the defense ministry website made the threat of pre-emptive destruction from the air more pointed by reporting on a meeting of officers from the U.S, South Korea, U.K., Canada and Australia (Korean War belligerents and members of the Task Force that found North Korean responsible for the Cheonan sinking) to, in the words of an unidentified participant, “check and reinforce joint military capabilities to secure airspace on the Korean Peninsula.”

On June 1, Yonhap reported that “President Lee Myung-bak instructed his Cabinet Tuesday to come up with a long-term strategy for the reunification of the Korean Peninsula, despite heightened military tensions following the sinking” of the Cheonan. Based on this alone, Lee’s real intentions are unclear. He is reported, however, to have said “national security has emerged as an important task since the Cheonan incident,” which now requires South Korea to “draw up a strategy on security bearing reunification in mind.”

The basic premise of Lee’s reunification strategy seems clear: north and south are to be reunited on South Korean (or US-South Korean) terms. A joining together of equals based on dialogue, mutual decisions and jointly implemented reunification policies can hardly be what Lee has in mind as his government ends inter-Korean trade and other bilateral cooperation, moves Lee told the South Korean nation on May 24 were necessary in response to Cheonan and other alleged North Korean provocations.

At a more extreme level, open speculation by senior South Korean government officials about pre-emptive attack and measures to bring North Korea’s economy to its knees conveys a willingness to, if need be, achieve reunification through turning North Korea into a wasteland.

Lee’s grand bargain is another sign of reunification on unilateral terms. The bargain seems to be a take it or leave it proposition. No room exists for arriving at reunification through mutual respect and negotiations between equals. In his recent appearance at the Asian security summit, Lee proposed putting his grand bargain at the center at any resumption of Six Party (South and North Korea, the U.S., China, Russia and Japan) talks, a proposal that seems to push aside the “action for action” negotiating principle all parties initially agreed would be at the heart of the talks, a principle that led to several important Six Party diplomatic achievements between 2005 and 2008.

While Lee contemplates a one-sided vision of reunification that may include military and economic coercion, the US has been helping to push the threat level even higher. On June 5 U.S. defense secretary Robert Gates warned of unspecified “additional options” under review for dealing with North Korea. The implication is a U.S. willingness to act outside the UN, using such unilateral measures as banking sanctions to punish any global financial institution active in the US market that tries to do business with North Korea.

Four days after South Korea released the statement on the Cheonan sinking, Hillary Clinton described the situation on the Korean Peninsula as “highly precarious.” Nevertheless, South Korea’s government is moving ahead with psychological warfare operations.6 Joint naval exercises with the US in the Yellow Sea (possibly including participation by the US aircraft carrier George Washington), planned and then suspended while the UN Security Council considers South Korea’s letter of protest over the Cheonan sinking, may still happen in the near future.

Responding to the possibility of a display of US-South Korean military might near Chinese territorial waters, the Global Times Chinese news website printed these June 8 editorial remarks in English:

“Though intended to send a threatening message to North Korea, having a US aircraft carrier participating in joint military drills off of China’s coast would certainly be a provocative action toward China,” “as a key player in the North Korea issue, South Korea should try hard to reduce the anxiety on the peninsula. Seeking gains by intensifying the tension is the wrong move. Escalation of the conflict will not be conducive to solving the issue” and “South Korea’s intentions are clear. That means it is up to the US alone to decide whether or not to deploy an aircraft carrier to the Yellow Sea. The US should be aware of the severe consequences such a move would bring.”

One other major power, and a participant in the Six-Party Talks that has been largely ignored in the discussion over the Cheonan, is Russia. The Russian news organization RIA Novosti reported on June 8 that “a group of Russian Navy experts left Seoul on Monday after assessing an international investigation that found North Korea responsible for the sinking of the warship [Cheonan] in March. The Russian experts did not draw their own conclusions on the issue.” An earlier RIA report stated that the group will report its findings to the Russian Defense Ministry sometime in the week ending June 12. How the defense ministry intends to handle the findings, which could include issuing a public report, is unclear.

While politics are in command of the Cheonan investigation, geopolitics and military events on the Korean Peninsula and in surrounding waters threaten to spin out of control, bringing the risk of a new Korean war.

Investigation result on the sinking of ROKS “Cheonan”

Posted May 20, 2010

Source: Ministry of National Defense, Republic of Korea

Opening Statement

The Joint Civilian-Military Investigation Group (JIG) conducted its investigation with 25 experts from 10 top Korean expert agencies, 22 military experts, 3 experts recommended by the National Assembly, and 24 foreign experts constituting 4 support teams from the United States, Australia, the United Kingdom and the Kingdom of Sweden. The JIG is composed of four teams–Scientific Investigation Team, Explosive Analysis Team, Ship Structure Management Team, and Intelligence Analysis Team.

In our statement today, we will provide the results attained by Korean and foreign experts through an investigation and validation process undertaken with a scientific and objective approach.

The results obtained through an investigation and analysis of the deformation of the hull recovered from the seabed and evidence collected from the site of the incident are as follows:

The JIG assesses that a strong underwater explosion generated by the detonation of a homing torpedo below and to the left of the gas turbine room caused Republic of Korea Ship (ROKS) “Cheonan” to split apart and sink.

The basis of our assessment that the sinking was caused by a torpedo attack is as follows:

- Precise measurement and analysis of the damaged part of the hull indicates that

— a shockwave and bubble effect caused significant upward bending of the CVK (Center Vertical Keel), compared to its original state, and shell plate was steeply bent, with some parts of the ship fragmented.

— On the main deck, fracture occurred around the large openings used for maintenance of equipment in the gas turbine room and significant upward deformation is present on the port side. Also, the bulkhead of the gas turbine room was significantly damaged and deformed.

— The bottoms of the stern and bow sections at the failure point were bent upward. This also proves that an underwater explosion took place.

- Through a thorough investigation of the inside and outside of the ship, we have found evidence of extreme pressure on the fin stabilizer, a mechanism to reduce significant rolling of the ship; water pressure and bubble effects on the bottom of the hull; and wires cut with no traces of heat. All these point to a strong shockwave and bubble effect causing the splitting and the sinking of the ship.

- We have analyzed statements by survivors from the incident and a sentry on Baekryong-do.

— The survivors made a statement that they heard a near-simultaneous explosion once or twice, and that water splashed on the face of a port-side lookout who fell from the impact; furthermore,

— sentry on the shore of Baekryong-do stated that he witnessed an approximately 100-meter-high “pillar of white flash” for 2~3 seconds. The aforementioned phenomenon is consistent with damage resulting from a shockwave and bubble effect.

- Regarding the medical examination on the deceased service members

— no trace of fragmentation or burn injury were found, but fractures and lacerations were observed. All of these are consistent with damage resulting from a shockwave and bubble effect.

- The seismic and infrasound wave analysis result conducted by the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources (KIGAM) is as follows:

— Seismic wave intensity of 1.5 degrees was detected by 4 stations.

— 2 infrasound waves with a 1.1-second interval were detected by 11 stations.

— The seismic and infrasound waves originated from an identical site of explosion.

— This phenomenon corresponds to a shock wave and bubble effect generated by an underwater explosion.

- Numerous simulations of an underwater explosion show that a detonation with a net explosive weight of 200~300kg occurred at a depth of about 6~9m, approximately 3m left of the center of the gas turbine room.

- Based on the analysis of tidal currents off Baekryong-do, the JIG determined that the currents would not prohibit a torpedo attack.

- As for conclusive evidence that can corroborate the use of a torpedo, we have collected propulsion parts, including propulsion motor with propellers and a steering section from the site of the sinking.

The evidence matched in size and shape with the specifications on the drawing presented in introductory materials provided to foreign countries by North Korea for export purposes. The marking in Hangul, which reads “1번(or No. 1 in English)”, found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo. The above evidence allowed the JIG to confirm that the recovered parts were made in North Korea.

Also, the aforementioned result confirmed that other possible causes for sinking raised, including grounding, fatigue failure, mines, collision and internal explosion, played no part in the incident.

In conclusion,

- The following sums up the opinions of Korean and foreign experts on the conclusive evidence collected from the incident site; hull deformation; statements of relevant personnel; medical examination of the deceased service members; analysis on seismic and infrasound waves; simulation of underwater explosion; and analysis on currents off Baekryong-do and collected torpedo parts.

- ROKS “Cheonan” was split apart and sunk due to a shockwave and bubble effect produced by an underwater torpedo explosion.

- The explosion occurred approximately 3m left of the center of the gas turbine room, at a depth of about 6~9m.

- The weapon system used is confirmed to be a high explosive torpedo with a net explosive weight of about 250kg, manufactured by North Korea.

In addition, the findings of the Multinational Combined Intelligence Task Force, comprised of 5 states including the US, Australia, Canada and the UK and operating since May 4th, are as follows:

- The North Korean military is in possession of a fleet of about 70 submarines, comprised of approximately 20 Romeo class submarines (1,800 tons), 40 Sango class submarines (300 tons) and 10 midget submarines including the Yeono class (130 tons).

It also possesses torpedoes of various capabilities including straight running, acoustic and wake homing torpedoes with a net explosive weight of about 200 to 300kg, which can deliver the same level of damage that was delivered to the ROKS “Cheonan.”

- Given the aforementioned findings combined with the operational environment in the vicinity of the site of the incident, we assess that a small submarine is an underwater weapon system that operates in these operational environment conditions. We confirmed that a few small submarines and a mother ship supporting them left a North Korean naval base in the West Sea 2-3 days prior to the attack and returned to port 2-3 days after the attack.

- Furthermore, we confirmed that all submarines from neighboring countries were either in or near their respective home bases at the time of the incident.

- The torpedo parts recovered at the site of the explosion by a dredging ship on May 15th, which include the 5×5 bladed contra-rotating propellers, propulsion motor and a steering section, perfectly match the schematics of the CHT-02D torpedo included in introductory brochures provided to foreign countries by North Korea for export purposes. The markings in Hangul, which reads “1번(or No. 1 in English)”, found inside the end of the propulsion section, is consistent with the marking of a previously obtained North Korean torpedo. Russian and Chinese torpedoes are marked in their respective languages.

- The CHT-02D torpedo manufactured by North Korea utilizes acoustic/wake homing and passive acoustic tracking methods. It is a heavyweight torpedo with a diameter of 21 inches, a weight of 1.7 tons and a net explosive weight of up to 250kg. [21 inches = 533mm]

- Based on all such relevant facts and classified analysis, we have reached the clear conclusion that ROKS “Cheonan” was sunk as the result of an external underwater explosion caused by a torpedo made in North Korea. The evidence points overwhelmingly to the conclusion that the torpedo was fired by a North Korean submarine. There is no other plausible explanation.

THU. 20 MAY, 2010

The Joint Civilian-Military

Investigation Group

* Government press release (May 20)

John McGlynn is a Tokyo-based independent foreign policy and financial analyst and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. He wrote this article for the Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: John McGlynn, “Politics in Command: The ‘International’ Investigation into the Sinking of the Cheonan and the Risk of a New Korean War,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 24-1-10, June 14, 2010.

Articles on related subjects:

The Hankyoreh, Russia’s Cheonan investigatin suspects that the sinking Cheonan ship was caused by a mine in water.

Seunghun Lee and J.J. Suh, “Rush to Judgment: Inconsistencies in South Korea’s Cheonan Report,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 28, 1, July 12, 2010

Tanaka Sakai, Who Sank the South Korean Warship Cheonan? A New Stage in the US-Korean War and US-China Relations. The original Japanese text is available here.

Michael Yo, Sleight of Law and U.S.-North Korea Relations: Re-nuclearization and Re-sanctioning.

Website from Korea with articles in English and Korean on the Cheonan incident.

Notes

1 The Hankyoreh reported on May 29 a Chinese proposal to activate the UN Armistice Commission, formed in accordance with the 1953 Korean War armistice, to investigate the Cheonan incident. If the proposal is accepted, an investigative team comprised of North Korea, South Korea, the US and China would be formed. The Hankyoreh‘s report has apparently been unconfirmed. However, the North Korean KCNA news service reported [http://www.kcna.co.jp/index-e.htm] on May 22 that North Korea issued a similar proposal for an armistice commission inquiry after South Korea turned down Pyongyang’s request to accept the dispatch of a North Korean investigative team. In the end, South Korea rejected both North Korean proposals.

2 An even more accurate description might be that the 5-page JIG statement is the product of an investigative process jointly directed by South Korea and the United States.

Yonhap reported on May 15 that Lee Yong-joon, South Korea’s deputy foreign minister, was in Washington D.C. for meetings with U.S. officials. Lee, in Yonhap’s description, “said South Korea and the United States are in sync over ways to deal with the Cheonan incident, although he added, ‘Details will be released after the outcome of the probe (into the sinking) is announced.'”

A later paragraph in the same Yonhap story is more suggestive of high-level government coordination: “Emerging from a meeting here with Kurt Campbell, assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, and Wallace Gregson, assistant secretary of defense for Asian and Pacific security affairs, Lee said, ‘There were no different opinions on the issue of the Cheonan, and we’ve agreed on all issues.'”

Important to note is that these meetings took place in Washington five or six days before the JIG investigative findings were released.

3 South Korea held regional elections on June 2. South Korea’s media generally portrayed the results as a surprising loss for Lee Myung-bak’s Grand National Party.

4 However, more than two weeks since the 5-page statement was issued, the 400-page report has not been released. Nor has there been any indication of whether, or when, the full report will be released.

5 In fact, the Obama administration’s April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review can readily be interpreted to mean that even if North Korea surrendered its nuclear weapons and fully accepted the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, it could still be targeted for U.S. nuclear attack (i.e., denied a “negative security assurance” or NSA from the U.S.) if it failed to meet “nuclear non-proliferation obligations” that remain unexplained in the NPR. One White House official, Gary Samore, coordinator for arms control and WMD, proliferation and terrorism, has stated those obligations could be expansive, ad hoc and unilateral. Speaking before the Carnegie Endowment on April 22, 2010, Samore said: “The point I’m making is that there are the clause in the NSA that says incompliance with their nuclear nonproliferation obligations is intended to be a broad clause and we’ll interpret that – when the time comes, we’ll interpret that in accordance with what we judge to be a meaningful standard.” Even if North Korea complies with the NPT, the model for what can still happen is Iran, the target of a relentless US-led international campaign to weaken the country through sanctions, using as pretext unproven allegations of a growing nuclear weapons potential hidden somewhere inside Iran’s NPT-compliant and UN-monitored civilian nuclear program.

6 For example, Yonhap reported on June 9 that South Korea’s military has completed installation of propaganda loudspeakers in “11 frontline areas” along the border with North Korea. The move is “part of the government’s punitive measures against North Korea for sinking” the Cheonan.