Japan, Israeli Settlements, and the Future of a Palestinian State

John McGlynn

Japan has been speaking out recently on the matter of Israeli settlements in Jerusalem and the West Bank Palestinian territory. At almost the same time, a senior official of the Palestinian Authority was in Tokyo seeking support from the Japanese government for a possible change in Palestinians tactics in their struggle for self-determination and statehood.

Illegal Settlements and the Responsibility of the World Community

On November 19, 2009, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign of Affairs issued a statement “deploring” Israel’s approval of the construction of nine hundred housing units in the Palestinian neighborhood of Gilo in East Jerusalem. The statement also reiterated a call by Japan for Israel “to freeze settlement activities including ‘natural growth’ in the West Bank which includes East Jerusalem.”

The comment by Japan added to an international chorus of criticism of Israel’s latest plan to build on Palestinian land in Jerusalem. US President Barack Obama said the action by Israel “embitters the Palestinians in a way that could end up being very dangerous.” Britain’s Foreign Secretary David Miliband said that the “decision on Gilo is wrong and we oppose it.” A “credible deal involves Jerusalem as a shared capital,” he said, so “expanding settlements on occupied land in East Jerusalem makes that deal much harder.” United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon reacted to Gilo by affirming “his position that settlements are illegal, and calls on Israel to respect its commitments under the Road Map [a peace plan that foresees two Israel and Palestine states living side by side in peace and security] to cease all settlement activity, including natural growth.” The current Swedish president of the European Union stressed that the EU’s position is that “settlement activities, house demolitions and evictions in East Jerusalem are illegal under international law.” Importantly, the president also noted that “such activities… threaten the viability of a two-state solution” and that the EU “has never recognized the annexation of East Jerusalem in 1967 nor the subsequent 1980 basic law,” in which Israel claimed Jerusalem, including the occupied eastern half, as its “undivided” capital.

Israeli settlements in the West Bank designated for development funding in December 2009

However warranted the criticisms voiced by Japan and other countries, they evade the fundamental reason why Israel has long been able to continue its occupation and settlement of Palestinian territories with impunity, which is that the international law consisting of resolutions approved by the UN Security Council, the General Assembly, and other international organs that renders Israel’s occupation and settlement activities illegal goes unenforced.

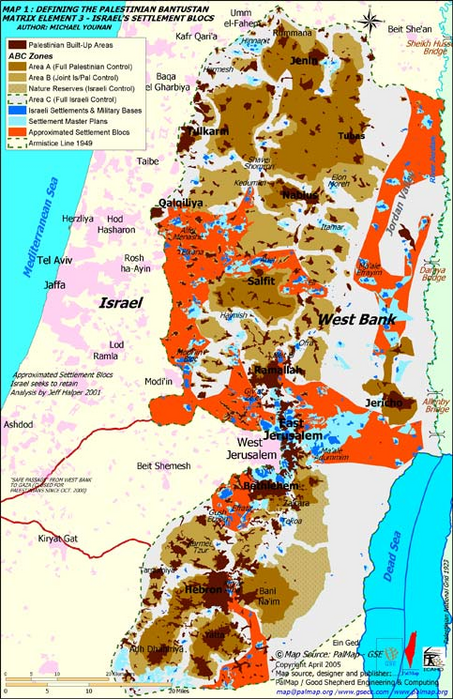

2005 map of Israel’s settlements in the West Bank

It’s no mystery why UN resolutions have gone unenforced. The basic reason was explained by Barbara Crossette, the former United Nations bureau chief for the New York Times. She wrote in January 2000 that

“with the exception of Iraq, actions taken on behalf of the UNSC on issues related to the Middle East have minimal importance. This is because Washington has tried—and largely succeeded—in keeping the Middle East out of the council’s deliberations. The Clinton administration has been especially vehement in keeping the Arab-Israeli peace process run out of the State Department and the White House and kept away from the UNSC.”

The same policy continued in the George W. Bush administration and, as US attempts to prevent any UN consideration of the Goldstone report condemning Israeli human rights violations in the 2009 Gaza War indicate, it now continues in the Obama administration. In support of this policy, the United States provides Israel with advanced weaponry (some of which is used against the Palestinians in violation of US law) and more than US$3 billion annually in financial support, along with including Israel in US geostrategic plans for maintaining control over the major political and economic developments (including the flow of oil) in the Middle East. All of these policies are downplayed by Washington and the US press but discussed openly in the Israeli press.

Japan’s diplomatic position on Israel and the Palestinians conforms to the international consensus of a two-state solution. In its fullest form, that position was outlined in May 2004 by then-Special Envoy for the Middle East Arima Tatsuo, who issued the following statement to coincide with a meeting of the Arab League Summit:

A comprehensive Middle East settlement is a key to the realization of the region’s peace and stability. As regards the conflict between the Israelis and the Palestinians, Japan supports its solution through the Road Map, which is the only path leading to a co-existence of two states, Israel and Palestine living side by side in peace and security. Japan believes that the so-called final status issues such as the border demarcation, the settlements and the return of the refugees should be resolved through negotiations between the two parties, the Israelis and the Palestinians, based on the relevant UN Resolutions, including UN Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, and on the principle of “land for peace.” Japan is of the position that, under international law, acquisition of land by force is not admissible and that measures undertaken under such acquisition do not constitute any basis for obtaining territorial title. Japan does not recognize, therefore, any changes to the pre-1967 borders other than those arrived at by agreement between the parties concerned.

There appears to be nothing in the diplomatic record that suggests Japan’s government has changed its position since 2004. As far as this author knows, the government has not issued any new statements on 242 since the DPJ came to power. On the other hand, in deference to Washington’s desire to keep the UN Security Council from enforcing its own resolutions relating to Israel and the Palestinians, Japan has no history (certainly not recently) of urging the Council to reexamine its failure to implement 242. Moreover, as discussed below, Japan distances itself from any responsibility to enforce international law by ending Israel’s occupation of Palestinian and its violation of human rights laws by regularly calling on the two sides, ignoring Israel’s lopsided power, to work harder to settle their differences.

Resolution 242, passed in 1967 in the aftermath of the Six Day War (supported by Resolution 338, passed in 1973 to bring the Yom Kippur War to a ceasefire), calls for the withdrawal of all Israeli forces from occupied Palestinian territories and forms the basis of any durable political settlement between the two sides. But the four-decade-long occupation and denial of Palestinian self-determination and human rights demonstrates that, without positive action by the international community, the implementation of the two resolutions to bring about a just and lasting peace will go nowhere.

European Union foreign affairs chief Javier Solana

This appears to be the rationale for a proposal made by EU foreign affairs chief Javier Solana, who in July 2009 called for the UN Security Council to assume responsibility for establishing a Palestinian state by a certain deadline if the two sides have not reached an agreement. The Security Council would then set border parameters for Israel and a new Palestinian state, and resolve the other permanent status issues on control of Jerusalem, refugees, and security.

But as Henry Siegman, the director of the US-Middle East Project and a former national director of the American Jewish Congress, has written, “this cannot happen without US assent and leadership, which is unlikely if such a proposal is incorrectly seen as punishment for non-performance, rather than understood as the original intent of resolutions 242 and 338, which called for Israel’s return to the 1967 borders.” In Siegman’s view, the Security Council has “responsibility for resolving the consequences of the Six-Day War if the parties were unable to do so,” a responsibility “implicit in the resolutions’ language, which stressed the inadmissibility of acquiring territory through war.”

Japan is silent on the Security Council’s implicit responsibility and avoids its own responsibility as a powerful and capable actor in the international community (and presently a member of the Security Council) to promote implementation of 242 and 338 as the basis for a two-state solution. Even worse, Japan renders itself counterproductive in the service of international law and justice by pretending that Israel and the Palestinians merely have to exercise sufficient goodwill to implement these resolutions. For example, a statement issued by Japan’s Foreign Ministry on November 26th on the “positive move” by Israel to suspend new settlement construction has this wording, commonly found in earlier government pronouncements: “It is incumbent on both Israel and the Palestinians to make more efforts to realize the two-state solution. Japan strongly hopes that the peace negotiations will be resumed under the agreement of both parties.” By making it a matter of a greater exercise of goodwill by a nuclear-armed regional superpower governed by a colonial expansionist ideology that has the political and material support of the world’s hegemon and an occupied defenseless people suffering from 60 years of military and economic oppression, except through homemade weapons and appeals to international law, such a call for evenhandedness only lets Israel off the hook.

It seems clear that with Israel-Palestinian negotiations long stalled, while Israel continues its inexorable building and consolidation of illegal settlements, that the Japanese diplomatic position, if it is a serious one, requires a focus on the positive steps the world community can take (such as the Javier Solana proposal) to finally implement 242.

Richard Goldstone (in short-sleeve shirt), Head of the UN Fact Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict, which produced the September 25, 2009 “Goldstone Report”

Japan’s current two-year membership on the Security Council provides it with a short-term opportunity to directly insert its views into top-level discussions about global security issues. However, Japan has done nothing to remind the Security Council of its responsibility to enforce its own resolutions ending the Israeli occupation, and has for the most part adopted a passive position in other UN deliberations critical to the Middle East. For example, Japan sits on the UN Human Rights Council, but recently abstained on a resolution passed by the Council by a vote of 25 to 6 (11 abstentions) in support of the Goldstone commission report, which recommends a judicial examination of the human rights violations and war crimes reported by the commission that were committed by Israel and the Palestinians during Israel’s “Cast Lead” invasion of Palestinian Gaza from December 27, 2008 to January 18, 2009, in which more than 1,300 Palestinians and 14 Israelis (including 10 soldiers) were killed.

As for Israel’s recent “positive move,” it’s not really so positive, for the reason that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in announcing the construction moratorium, said that it would only last ten months, not affect construction in progress, and not include “the schools, the kindergartens, the synagogues, and public buildings necessary for the continuation of normal life over the period of the suspension.” Netanyahu added that the moratorium would not apply to Jerusalem (Israel claims sovereignty over the entire city, while the Palestinians want the eastern section as the capitol of a future state).

Bernard Avishai, an adjunct professor at Hebrew University and the author of three books on Israel, adds that the moratorium “does not take into account that the actual drivers of new settlement are not in the government, but fanatic settlement organizations that have been acting more or less independent of government decisions for years, and which the state does not have the manpower (or the army, the stomach) to confront with military force.”

Japan and a Possible Palestinian Declaration of Statehood

On November 17th, shortly before the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s two statements, a senior official of the Palestinian Authority visited Japan to urge Tokyo to support the authority’s efforts to secure statehood. As reported in Japan Today, Hasan Abu-Libdeh, national economy minister, told a news conference in Tokyo that he planned to discuss obtaining Japanese government support for the outline of a Palestinian state. “I believe the Japanese government can exercise some of its weight not only directly but also with other… friends who have relationships with Israel,” he said, which one media source described as a reference to Japan’s influence made possible by its alliance with the United States.

Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) headquarters in Tokyo

The visit probably has several underlying reasons. One is that the Palestinians want to ascertain the position of the Japanese government now that the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) is in power. While Japan failed to support Palestinian calls for justice by declining to support the Goldstone report, its new strategy for Afghanistan and Pakistan, which calls for spending US$5 billion on police training and civilian assistance projects in Afghanistan and economic aid to Pakistan rather than committing Japanese troops to US-NATO military operations, is one sign that Tokyo may be rethinking the extent of its cooperation with Washington’s foreign policy initiatives. It’s noteworthy that Japan announced its strategy before Obama’s recent visit to Tokyo, even though White House advisors had made it clear in advance that Obama would be discussing how Japan could support the US-NATO military mission in Afghanistan.

There are other signs of pushback and an end to the days of automatic capitulation to Washington as was the practice under the Liberal Democratic Party, Japan’s governing political party for some 50 years. Under the DPJ, the central government is now investigating and has announced plans to publicly report on a secret US-Japan pact on the transport of nuclear weapons through Japanese territorial waters, appears serious about reducing the burdensome concentration of US troops in Okinawa and seems to want to keep the US at arms length as it pursues an independent policy of more tightly integrating Japan into the Asian community of nations. All these initiatives at least suggest the possibility that the new DPJ government might be open to new thinking on Israel and the Palestinians. If the DPJ is amenable to a new approach, that could be useful to the Palestinian strategy of seeking UN support for statehood, which connects to the likely second reason for the Tokyo visit by the Palestinian economy minister.

The visit came several days after the Palestinian leadership announced a medium-term plan to go to the United Nations to ask for a declaration of a Palestinian state within 1967 borders (i.e. in the West Bank and Gaza). The move comes because the Obama administration’s attempts to restart the peace process have failed. The Palestinian leadership had made an Israeli settlement freeze a prerequisite for new talks, and so refused to sit down with the Israeli government as long as the latter continued to build on Palestinian land (Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas has dismissed Israel’s moratorium on new settlement construction because it did not apply to several thousand housing units and public buildings in the West Bank and to eastern Jerusalem.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, right, consults with Chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat, left

As reported in Haaretz on November 15th, Chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat said that the Palestinians had decided to go before the UN Security Council after eighteen years of fruitless negotiations with Israel: “Now is our defining moment. We went into this peace process in order to achieve a two-state solution. The endgame is to tell the Israelis that now the international community has recognized the two-state solution on the ‘67 borders.”

The likely Palestinian strategy behind a unilateral declaration is explained [link]by Jeff Helper, co-founder and Coordinator of the Israeli Committee Against House Demolitions (ICAHD):

Rather than a general declaration of independence, the Palestinian Authority would declare a Palestinian state within specified borders, those of 1967 (the 1949 armistice line), which have already been recognized de facto over the years, from UN resolution 242 to the Road Map. Specifying the borders is what would differentiate this initiative from previous declarations based on principle of independence but without territorial claims, the latter supported even by Israel since it relieves it of pressures to end the Occupation by giving the Palestinians symbolic sovereignty.

The reasoning behind such an initiative is clear: to reverse both the balance of power and the dynamics of the negotiations. Because it occupies Palestinian territory, Israel is able to negotiate from a position of strength, while the Palestinians, with no leverage whatsoever, have no way to pressure Israel to meaningfully withdraw. Appeals to international law, which would have leveled the playing field, were nullified after the US, de facto supporting Israel’s claim that there is no occupation, classified the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza as disputed territories [a classification made during the George W. Bush administration: JM]. Instead of requiring Israel to relinquish its illegal settlements and other forms of control, this policy forces the Palestinians to negotiate every settlement, road and centimeter of land, unable in the end to compel Israel to make any concessions it does not want to make. By seeking international recognition of the Palestinian state within recognized borders, including membership in the UN, the Palestinians seek, finally, to end the Occupation while transforming Israel’s presence from that of an occupying power to one of an invader whose unilateral military and settlement activities, as well as its extension of its legal and planning systems into Palestine, constitute nothing less than an intolerable violation of Palestinian national sovereignty.

For a unilateral declaration of statehood to be accepted by the international community, the Palestinians first need to shore up support from major countries like Japan for the concept of a Palestinian state situated inside pre-1967 borders (though not yet for statehood itself). An endorsement from Japan together with that of several other big countries could become a way to maneuver past de facto non-recognition of, or active opposition to, pre-1967 borders by the United States (see the final paragraph for the apparent current US position on recognition) and generate momentum for a UN General Assembly resolution in support of Palestinian statehood, which in turn puts pressure on the Security Council, including the United States, to finally implement a solution along the lines of 242. The task will not be easy. In 1988 the Palestinian Liberation Organization declared Palestinian independence but without reference to borders. The declaration was recognized by dozens of states but not any major western state and not Japan.

If international acceptance of a unilateral declaration of statehood is the Palestinian strategy, it has already met with success—but with the United States, not Japan (at least not yet with the latter). In the hope of getting the Palestinians to return to the negotiating table and avoiding a media and popular judgment that the Obama administration’s efforts at diplomacy in the Middle East have completely failed, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton declared on November 25th that the United States believes that “through good-faith negotiations the parties can mutually agree on an outcome which ends the conflict and reconciles the Palestinian goal of an independent and viable state based on the 1967 lines, with agreed swaps, and the Israeli goal of a Jewish state with secure and recognized borders that reflect subsequent developments and meet Israeli security requirements.” Instead of the “disputed territories” formulation that was designed by the Bush administration to sever US policy from a 242 solution, Clinton’s words re-establish 242 and pre-1967 borders as the main geographic outline of a Palestinian state.

This is a slightly modified and updated version of an essay prepared for the Shingetsu Institute (www.shingetsuinstitute.com) on November 30, 2009.

John McGlynn is a Tokyo-based independent foreign policy and financial analyst and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

Recommended citation: John McGlynn, “Japan, Israeli Settlements, and the Future of a Palestinian State,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 52-1-09, December 28, 2009.