Taniguchi Shoko

Translated and introduced by John Breen

Introduction

On Saturday 25 August 2007, NHK broadcast a programme called Seishonen no jisatsu o kangaeyo [Let’s reflect on youth suicide]. The programme was prompted by the National police agency’s publication of new statistics on the problem of youth suicide. In 2006, 886 Japanese youths took their own lives, invariably in response to bullying. ‘Youth’ as defined by the NPA refers to primary, middle, secondary school as well as university students. The 2006 figure was the highest since records began. It comes hard on the heels of other statistics demonstrating that Japan’s annual suicide figures have hit 30,000 for the 9th year in succession.

What made the NHK programme gripping was not the format, a very conventional round-table discussion, albeit one ably and compassionately chaired by Machinaga Toshio. Rather, it was the calibre of the guests invited. There were a couple of ‘professionals’, but more captivating were the contributions of Shinohara Eiji, a Buddhist priest who has devoted his life to counselling would-be suicides. As a young boy he survived his mother’s attempt to kill him as she tried to kill herself. He has opened his temple in Narita, Chiba prefecture as a counselling centre to young would-be suicides. There was also Okouchi Yoshiharu, father of Kiyoteru, a thirteen year old middle school student from Nishio city near Nagoya prefecture, who took his own life in 2004 after enduring bullying at school whose cruelty defies belief. His father now works for Nishio city as a counsellor, and with his wife they provide sanctuary to victims of bullying who are contemplating suicide. Both men spoke movingly about their work with young people.

Also participating were three young women, who had all contemplated suicide in response to bullying of one sort or another. One girl, an anexoric aged 26, whose problems began in middle school when class mates instructed her to lose weight, spoke of the redeeming touch of her father. Her father greeted her home from hospital after she had cut her wrists in an attempted suicide, and for the first in his life embraced her. She said how awkward it had felt at first to be embraced by him, but this silent act made her realise her life was worth living. All three girls concurred with Shinohara that what they all needed was ai o kometa osekkai. Ai o kometa means ‘accompanied by’ or perhaps here ‘inspired by’ love, and osekkai ‘meddling’ or ‘interference’. Shinohara meant by this that parents, school and society should all interfere, demand to know what is going on, but they should do so motivated by love.

The participants in the round table discussion reached the conclusion that suicide was not just the problem of the individual taking his or her young life, but a social problem demanding a social response. This may sound bland in the extreme, but it seemed anything but bland in the context of the programme’s varied testimonies from the likes of Okouchi and Shinohara, as well as the three young girls. Indeed, it is Japanese society’s failure thus far to tackle suicide with any real effect that make this conclusion entirely apposite. The article by Taniguchi Shoko, which I have translated here, reaches precisely the same conclusion: that suicide has been for too long in Japan an ‘unspeakable death’ (katarenai shi), a problem for the individual and not one which need concern society as a whole. Taniguchi offers a cool appraisal of the present situation in Japan, locates it in a comparative perspective and sketches in some recent, if belated, initiatives sponsored by the state, as well as private groups, to tackle suicides by the most vulnerable group, middle aged men.

Readers who wish to explore further the issue of youth suicide and, indeed, how young people are affected by the suicides of their parents, are referred, initially at least, to the blog written by Machinaga Toshio in the aftermath of the NHK programme. Addressed specifically to teenagers, Machinaga calls his blog simply Jisatsu ni tsuite katatte miyo [Let’s talk about suicide]. He begins by reminding his readers that Japanese suicides over the last ten years have eliminated the equivalent to the population of a small town. 10 times as many people attempted suicides in each of those years as succeeded, and Machinaga asks us to assume that that each one of these has, say, five relatives. We should all ponder how many millions of Japanese over the last decade have been directly affected by suicide. Machinaga’s blog can be accessed here:

JB

Suicide is a social not an individual problem

Visualising the truth of the unspeakable death

Japanese suicides exceeded 30,000 in 1998 for the first time

For nine years in succession now, Japan has maintained the same 30,000 level; the leading cause of death for 20-39 year olds is suicide.

Real suicide prevention measures must begin now, but how to ensure they are effective?

Taniguchi Shoko

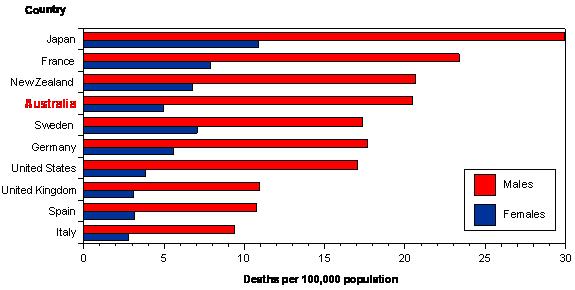

Japanese suicides, according to statistics of the National Police Agency, exceeded 30,000 in 2006 for the ninth year in succession. Japan is one of a very small number of the world’s ‘suicide giants’. Comparing rates with those of other major nations, Japan’s level is conspicuously high: it ranks second after Russia; it has twice as many suicides as the US, and three times as many as the UK. Last year the Japanese government enacted the ‘Basic Suicide Prevention Law’ (Jisatsu taisaku kihon ho), and on 8 June this year, the cabinet approved the Framework (Ozuna), which comprises a number of concrete measures. The Framework sets out the responsibilities of the national and regional authorities that are to debate suicide prevention measures before they put them into practice. The Framework is, in brief, an outline for the state’s strategy to reduce the suicide numbers.

One of the major concerns of the Framework is to enhance research and so expose the truth about suicide in Japan. The fact is that while Japan has entered the era of 30,000 suicides per annum, the government has till now failed to expose the true face of suicide in Japan; that is to say it has thus far shed no light on the social background to suicide.

In 1998, suicides increased by 8,500 over the previous year to reach the 30,000 mark, and a major reason for the surge can be found in the financial uncertainties and the deterioration of economic fortunes after the bubble burst. Since 2004, the Finance Ministry has been reporting a quiet economic recovery, and yet there has been no reduction in suicides. Why is this?

Suicides by managers of medium to small enterprises and economic recovery: the link

In the discourse of market fundamentalism, which holds sway in the new liberal economy of Japan, the economy recovers and social bifurcation is corrected. The major banks are making big profits, the public debt is being paid off, and still the government adopts measures to alleviate the corporation tax burden of listed companies, as major businesses transform their employment practises, sacking employers in the name of restructuring. At the same time, small and medium businesses are struggling, and going under as banks are reluctant to lend. The shuttered shops to be seen along any street in urban Japan tell their own story.

Professor Otomo Nobukatsu of Ryukoku University’s Social sciences department comments: In fiscal year 2005 alone, consumer finance companies, having had borrowers insure their lives with the finance companies as the beneficiaries, struck it rich. The five major consumer finance companies along had 39,880 cases of payment of death benefits, of which 3649, approximately 10 percent, were by suicides. Consumer finance companies collected harshly using “life” of their clients as security.

Mr. Sato Hisao used to run a medium-sized real estate business in Akita. In 2000, he was forced to declare his business bankrupt. Prompted by the suicide of an acquaintance, in 2002 Sato founded a non-profit organisation he called Kumo no su or the Spider’s web. Its founding purpose was to prevent suicide by managers. At present he is engaged in a never-ending struggle, day and night, as he counsels managers of medium and small enterprises. Sato says: ‘Managers burdened with heavy debt typically commit suicide prior to bankruptcy. But there are three ways in which they might choose to shoulder responsibility: they take flight; they take their own lives or they simply get on and take care of unfinished business. Bankruptcy is the collapse of economic activity, and there is no need for anyone to rely on life insurance and make amends with one’s life. What I do is spend a great deal of time discussing with managers the ways available for them to settle their affairs, and I listen attentively too to their psychological difficulties.’

Akita prefecture leads the way in suicide prevention

The suicide rate in Akita prefecture has been the highest in Japan since 1995. A glance at the rates for different prefectures of Japan in 2006 reveals that those topping the list are in the Tohoku region: Akita 42.7 %, Iwate 34.2%, Yamagata 31.7%.

These prefectures are, moreover, those which have pioneered suicide prevention. Professor Motohashi Toyo of the Akita University medical school (Department of Public health), who has been actively engaged in suicide prevention, explains as follows: ‘After the rapid economic growth of the late 50s and 60s, high suicide rates spread out from the urban periphery to under-populated regions like Tohoku. It is now understood that socio-economic factors have a major impact on the regional variations apparent in suicide rates. I refer to such things as the depopulation and aging of the agricultural prefectures, as well as changes within the communities and family relationships.’

Comparing urban with rural areas, there can be no denying that suicide rates in the latter are high, but a different picture emerges when we contrast absolute numbers of suicides. The absolute number in urban areas is overwhelmingly greater. So while the rate of Akita suicides is the highest in all Japan, the total number of suicides is a mere 482. By contrast, the municipalities of Tokyo and Osaka scored 2,502 and 1,965 respectively. Moreover, the figure for the whole of the metropolitan area, which is taken to include Kanagawa, Saitama and Chiba as well as Tokyo, is 6,925. (Vital statistics (Jinko dotai tokei) 2006). Professor Motohashi insists: ‘It is imperative that suicide prevention measures are fully functioning in the urban areas, given the total numbers of suicides. In order to reduce the total number of suicides, which stand in excess of 30,000 per year, we must pay heed not only to the rates but to the absolute numbers. It is incumbent on both central government and local authorities to implement suitable counter measures.’

In Japan it was always the practice to regard suicide as an individual problem, but given the rise of suicides triggered by the stresses of overwork, there is now at last a growing awareness that such suicide is a social problem. As long as suicide is regarded simply as the problem of the individual who has taken his or her life, there can be no progress in suicide prevention. It is essential to shed light on the factors in the social background to suicide.

Finland’s acclaimed suicide strategies

Finland is renowned as the first country in the world to have launched, and scored success with, a state-led suicide strategy. The Finnish project was carried out between 1986 and 1998. During this period, epidemiological research was conducted with a psychiatric method involving the ‘psychological dissection’ of the suicide before his or her death. The research revealed yet again the connectivity between depression and suicide, and this prompted in Finland a widespread awareness of the need for preventive measures. The Finnish project clarified the multi-layered nature of suicide causes. From 1992, the Finnish Health and Welfare Research Institute (STAKES) responded by activating a range of social networks, and deploying a number of mutually-influencing suicide prevention measures in as many as 40 different projects. These included ‘Suicide prevention and mass media’, ‘The depression project’, ‘Care for failed suicides’ and ‘Crisis intervention in schools’.

As a consequence, the suicide rate dropped about 9% compared with pre-1996 levels. This amounted to a 30% reduction compared to the worst period. Finland faced economic crisis with the historic collapse of the Soviet Union, and suffered a soaring unemployment rate too but, despite this, it managed to reduce its suicide rates. This achievement earned the Finnish universal acclaim. Finland is also known for having the best-educated children in the world. Like other northern European countries, women have entered the labour market in large numbers, and the social welfare system is thoroughgoing. All these social factors need to be borne in mind.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) broadcast the following message to the world ahead of Suicide Prevention Day: ‘Suicide is a major, but for the most part preventable, public health issue. Suicide accounts for nearly half of deaths by violence, and it is the cause of death for nearly a million people annually. Suicide inflicts on the globe billions of dollars of loss in economic terms.’

This is Professor Motohashi on the need for suicide prevention strategies: ‘Thanks to the WHO message, there is a growing understanding across the world that suicide is a form of death which, through the efforts of society, is perfectly avoidable. If we consider the numbers of Japanese suicides since 1998, we can surmise that in excess of 80,000 more people have died than needed to. It is not the case that most suicides take their lives with a clear wish to do so. The emotional state of suicides just prior to death reveals they suffer from emotional sicknesses such as depression or alcohol dependency. In this sick state, they plan suicide, they feel guilty, they attempt suicide and often fail before succeeding. Surely it is time for us to understand that suicide is a social problem and that improvements in the social system, to help those suffering from massive debt, for example, will link directly to suicide prevention.’

New public-private projects are launched

The NPO ‘Suicide Prevention and Support Centre: Life link’ (Jisatsu taisaku shien senta-, raifu rinku [Director Shimizu Yasunori]) contributed hugely to the establishment of the afore-mentioned ‘Basic Suicide Prevention Law’. [1] ‘Life link’ has now taken advantage of that law, and of the Cabinet’s approval of the Framework, to make of 2007 ‘Year 1 in the global prevention of suicide’. Life link is also now launching a new project, ‘The country wide caravan offering support to the bereaved of those who take their own lives (Jishi izoku shien zenkoku kyaraban)’.[2] Life link’s assistant director Nishida Masahiro explains: ‘The families and the children bereaved by suicides go through anxieties and suffering which they cannot speak of, even to closest friends. Lifelink offers support by creating spaces the length and breadth of Japan for sharing (or grief work) with people experiencing the same dilemma.’ Lifelink serves as the administrative headquarters for ‘The country wide caravan’, and its executive committee is co-hosting, along with the Cabinet office, a major conference in Tokyo on July 1. The event is styled ‘Talking of suicide: a public-private forum for a new era of suicide prevention’ (Jisatsu o kataru koto no dekiru shi e: jisatsu taisaku shinjidai, kanmin godo shinpojiumu [Inquiries: 03 3261 4934] ). The Country-wide caravan begins its 20-stop tour in Akita prefecture on 15 July.

The social pathology of the major economic power which Japan has become is profound, what with ‘the unspeakable death’ that is suicide, and ‘invisible poverty’. The first priority must be to render these problems visible.

Translator’s Notes

[1] See the Life link website

www.lifelink.or.jp/hp/tsudoi.html

[2] More information on the caravan is available here www.lifelink.or.jp/hp/caravan.html

This article was published in the June 22, 2007 issue of Shukan Kinyobi (Weekly Friday). Taniguchi Shoko is a journalist.

John Breen teaches Japanese and Japanese history at SOAS, University of London. He is the editor of Yasukuni, the war dead and the struggle for Japan’s past, forthcoming from Hurst/Columbia University Press. He translated and introduced this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on August 28, 2007.