[Summary in Italian available here]

Yasukuni is first and foremost a site for the performance of ritual before the kami (gods), those men, women and some children who sacrificed their lives for the imperial cause. This article examines the organizing of space and ritual at Tokyo’s shrine to the war dead and the implications for memory.

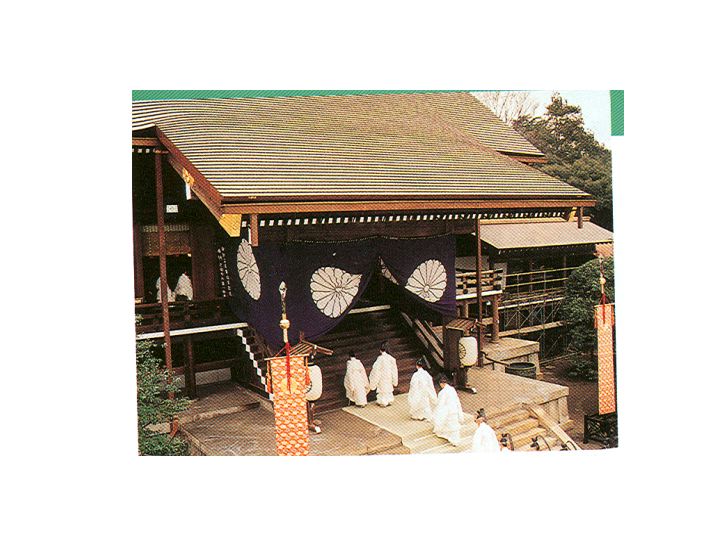

The most important of several ritual spaces is that within the Honden or Main sanctuary. This is the central, elevated building located along the east-west axis that runs up from the bottom of Kudan hill. It is within the deepest darkest recesses of the Honden that the kami reside; there that priests make them offerings every morning and evening every day of the year. The other buildings along the main axis are the Haiden or Worship hall and the Reijibo hoanden or Shrine archive. The pilgrim to Yasukuni passes under the first torii at the bottom of Kudan hill, through the wooden gate and under the second and third torii to confront the Worship hall. It is here that pilgrims bow their heads, clap their hands before the Yasukuni kami. On more formal occasions, the pilgrim enters the Worship hall and observes the ritual activity in the Main sanctuary across the garden that separates the two buildings. The Honden was built in 1872 and the Haiden in 1901. The Repository, constructed of earthquake proof reinforced concrete directly above the Yasukuni air raid shelter, is more recent. It was built in 1972 with a private donation from the Showa emperor, Hirohito.

The Main Sanctuary (Courtesy of Yasukuni Shrine)

On the north south axis are two other sites of significance: to the north of the Worship hall is the Yushukan war museum, an integral part of the shrine precinct, and to the south the Chinreisha or spirit pacifying shrine, a site of considerable controversy. In this and any discussion of Yasukuni, it is important to acknowledge that the shrine is first and foremost a ritual site and that it is also, for this very reason, a keeper of complex and conflicting memories. All of the sites are keepers of memory and in what follows, I explore the meaning of each in turn: the Main sanctuary, the Yushukan war museum and the Chinreisha. [1]

The Main sanctuary

Of the many rites that Yasukuni priests perform during the course of the year, the most important are the great Spring and Autumn rites. What distinguishes them above all is the presence of an emissary (chokushi) dispatched from the imperial court. The emissary, clad in Heian court garb, brings from the imperial palace the emperor’s offerings of silk in five colours to add to those which the shrine priests place before the kami at the start of the rites: beer, cigarettes, water and rice wine. The dynamic in this and all Yasukuni rites involves an exchange: here it is the propitiation of the kami by the emperor (in the person of his emissary) and by priests with offerings; in return, the kami bestow their blessings upon the emperor, Japan and all Japanese of the realm. The kami demand constant propitiation lest they be distracted for a moment from bestowing their blessings; lest also their benevolence might transform itself into a malevolent power. Rites at Yasukuni, therefore, share much in common with the genre of chinkon, or spirit pacifying, rites. Ancestral rites are the best-known examples of the genre; the cult of angry spirits that began in Heian Japan is another example. Shrine priests insist though that their kami are to be thought of as ancestors of the living and not as angry spirits.

The imperial connection is absolutely fundamental to an understanding of Yasukuni and the meaning of its rites. The imperial emissary is the most striking symbol of that connection, but it is everywhere apparent. Imperial princes regularly attend shrine rites to this day, though the present emperor has not visited since his enthronement and his father, emperor Showa, visited for the last time back in 1975. He intended to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the war, but 1985 was the year in which Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro’s visit caused a major diplomatic incident with China. It was deemed undiplomatic for the emperor to visit, and he never returned.

The shrine is marked with imperial symbols: the 16-leaf chrysanthemum embossed on the wooden gate, the chrysanthemum patterned curtains that adorn the Worship hall and the Main sanctuary; the mirror that dominates the interior of the Sanctuary, a personal gift from the Meiji emperor. Yasukuni is, moreover, designated chokusaisha or ‘shrine for imperial offerings’. Indeed, the Yasukuni ritual cycle incorporates rites of the imperial court: so the shrine performs the Niiname and Kanname rites; it celebrates the anniversaries of Jinmu, Meiji, Taisho and Showa. Finally, the Shrine archive was built by the Showa emperor, and symbolizes the fact that the war dead are the emperor’s war dead. The imperial connection constitutes a most significant thread of continuity with pre-1945 when Yasukuni shrine rites, attended by the emperor in person, became the vibrant centre of the imperial cult.

The imperial presence, in the person of the emissary, gives to the Great spring and autumn rites an intriguing ambiguity. This was always the case from the moment when, in the 5th month of 1869, the Meiji emperor marked the shrine’s foundation with the dispatch of an emissary to honour the 3,588 dead in the civil war. Now, as then, the emperor propitiates the war dead bringing them solace with his presence and his offerings of silk. He is doing more than this of course: he is honouring the values of patriotism, bravery and self-sacrifice which all of the dead are assumed to have embodied in their deaths. These were values which were sustained and given meaning by the imperial institution: it was for the emperor that the dead made the ultimate sacrifice, and by the emperor they are now being recompensed. The ambiguity concerns the question of who venerates whom at Yasukuni. For there is a real sense in which even as the emperor makes his offerings to the war dead, so the war dead and the living gather at Yasukuni to venerate the imperial presence.

As a dynamic site of memory, then, Yasukuni recalls through its Great spring and autumn rites in the Main sanctuary — and it idealises — a time when the imperial institution and imperial values defined society; when all men were motivated by a sense of patriotism, of courage and selflessness. Yasukuni rites preserve the memory of a war in which all deaths were selfless acts of bravery on behalf of the imperial institution; of a war which was only ever noble and glorious.

The Absent enemy

All participants to the Great spring and autumn rites are actively encouraged to visit the Yushukan war museum, which sits to the north side of the Main sanctuary. Free tickets ensure that crowds gather in the museum after the performance of rites. Ever since the museum was first re-opened in post war Japan in 1985, it has always been regarded as inseparable from the shrine; its exhibits constitute a sort of illustrated commentary on the shrine’s ritual activity. This remains the case today with the greatly expanded and refurbished Yushukan that opened its doors to the public in 2003.

The Yushukan shares much in common with war museums of former imperialist powers everywhere: its exhibits tend towards the glorification of sacrifice and acts of astonishing bravery on the part of soldiers who fought for the empire; they deploy technology, too, to sanitise the horrors of war. The C56 steam engine that confronts the visitor in the reception hall is a case in point. The plaque attached says ‘This engine was built in 1936; it was used on the Burma railway, and for a decade after the war too it continued to ply the same route.’ ‘The building of the railway [it adds] was difficult in the extreme’. That this ‘difficulty’ entailed the deaths of some 90,000 prisoners of war and local laborers, as well as many Japanese, is not referred to.

The life size models of the Oka and the Kaiten that decorate the entrance hall make the same point. The Oka were flying contraptions packed with explosives. They were released from their ‘mother’ plane when the enemy fleet hove into view and the pilot, with only the most primitive steering gear, would endeavour to crash it into enemy warships. The Kaiten was a manned torpedo equipped with a small engine and steering device designed to be steered by its pilot into the hulls of enemy vessels. The plaques attached to these machines are full of fascinating technological detail, but there is no encouragement to recall the destruction they caused. But this is not unique to the Yushukan.

What is perhaps unique to the Yushukan war museum — it certainly offers a striking contrast to, say, the Imperial war museum in London — is the curious absence of the enemy. The visitor to the galleries on the Sino-Japanese war, the Russo-Japanese war, the Manchurian ‘incident’ and the Pacific war looks in vain for a sighting of the enemy. There are no representations of Chinese, Russian, Korean, American or British soldiers; no weaponry, uniforms, flags or other trophies of war. A Yasukuni priest explained this was because the Yushukan was not really a museum at all, but an ‘archive of relics’. The Yushukan does refer to itself in its own publications, however, as ‘the oldest war museum in Japan’ and, the point is that, like museums everywhere, the Yushukan exhibits construct a narrative about Japan’s modern wars; the absence of the enemy distorts the narrative. It disguises two deeply hurtful facts about the Pacific war: the first is the fact of perpetration; the second the fact of defeat. Relics of Chinese, Russian, Korean, American or British soldiers would recall the defeats suffered by the Japanese army, and might also bring to mind the wrongs that Japan perpetrated. By eliminating the enemy, the Yushukan remembers a war that was only ever glorious; it obliterates the possibility that not all the Japanese war dead died glorious deaths, that lives lost (Japanese or others) were lives wasted, and that war was brutal and squalid. The exhibits prompt reflection only on heroism, loyalty and self-sacrifice.

The visitor reaches the end of the Yushukan gallery on the Pacific war to discover that, though the enemy is entirely absent, there is a striking foreign presence. The gallery concludes with a photograph, magnified perhaps ten times, of Justice Radhabinod Pal. Justice Pal was the one Asian judge at the war crimes tribunal in Tokyo, and it was his considered view that the Japanese were innocent of all war crimes, and that the real aggressors in Asia were British and American imperialists. Justice Pal’s views are reproduced by the side of his portrait. They make for a striking and a dramatic end to the gallery.

The curious absence not only of the enemy but also of the peoples conquered by Japan’s armies enables the Yushukan to recall a glorious war of liberation: Japanese soldiers fighting heroically and successfully to liberate Asia.

Pacifying the myriad spirits

Visitors to the Great spring and autumn rites are not encouraged to visit the Chinreisha or Spirit pacifying shrine. In fact, the vast majority of them are entirely ignorant of its presence. This is because the Chinreisha sits to the southern side of the Main sanctuary enclosed by a steel fence. The shrine was built in 1965 and the steel fence was erected a decade later. The reason for the construction of the fence, as explained to this author, was that the chief priest at Yasukuni had received intelligence that unknown persons were planning to blow the Chinreisha up. It is clear, however, that the very existence of the Chinreisha is a matter of great controversy within the Yasukuni priesthood. Why would anyone want to blow it up; what makes it controversial?

The Spirit Pacifying Shrine (Courtesy of Yasukuni Shrine)

The Spirit Pacifying Shrine (Courtesy of Yasukuni Shrine)

The Chinreisha is a simple, inconspicuous wooden structure that contains two za or seats for the kami. One is dedicated to all of those Japanese who died in domestic wars or incidents since 1853 and who are not enshrined in the Main sanctuary. So the men who fought against the imperial army in the civil wars of 1868-9 are venerated there since the Main sanctuary only venerates the imperial dead. Enshrined in the Chinreisha too are men like Eto Shinpei and Saigo Takamori, erstwhile government leaders who subsequently rebelled against the imperial government and took their own lives before capture.

A second za is still more controversial since it is dedicated to all the war dead regardless of nationality: British, US, Chinese, Korean, South East Asian. In the Main sanctuary there are also foreign war dead enshrined: Koreans, Chinese and Taiwanese. But these men died fighting for the imperial army. The Chinreisha dead by contrast were the enemies of imperial Japan. Although the Chinreisha is now secluded from view, and its existence unknown even to most of the war veterans who patronize Yasukuni, it is a key ritual site. It has an annual festival held on July 13th. It is accommodated within the Great Spring and Autumn rites to the extent that offerings are placed before the Chinreisha kami on these occasions — though not by the imperial emissary. Indeed, the native and foreign kami enshrined in the Chinreisha are propitiated with rice offerings in the morning and evening every day of the year.

What is interesting about the Chinreisha in the present context is that it has the capacity to recall a more nuanced past, a past of perpetrators and of victims, of winners and losers, of horror as well as heroism. It is precisely this past that the shrine authorities seem anxious to bury. The last Chief priest, Yuzawa Tadashi, was known to be vigorously opposed to removing the fence and exposing the Chinreisha to the public. He was replaced at the end of 2004 by a man called Nanbu Toshiaki. Like most Yasukuni chief priests, Nanbu never trained as a Shinto priest; like most, he is an aristocrat. Nanbu’s pedigree is particularly interesting though. He is descended from the Nanbu family who ruled Morioka domain in the Tokugawa period. Morioka, of course, was one of the domains in the great northern coalition that fought against the Meiji government in 1868. His ancestors are enshrined in the Chinreisha. It is early yet to know whether Nanbu will adopt a more open attitude toward the Chinreisha, which might make it possible for Yasukuni to generate a more complex memory of Japan’s imperial past.

Conclusion

I have here addressed the question of memory through a cursory exploration of the multiple sites within the Yasukuni precinct. It is perhaps worth finally making reference to two other categories of memory which Yasukuni entertains. The first relates to the shrine repository (reiji bo hoanden). It is not widely acknowledged, but the repository contains unquestionably the most accurate records of those who died in Japanese uniform during the Pacific war.

For every one of the kami venerated in the main sanctuary at Yasukuni, there are files, presently being digitalized, containing personal details. The latest shrine figures for the dead are as follows: the Manchurian ‘incident’ 17,176, the China war 191,250, and the Pacific war 2,133,915. I say ‘the latest figures’ because those for the Pacific war change. Last year, the shrine enshrined 12 new kami. Families of the war dead inquired of the shrine whether their fathers, brothers or uncles were venerated at Yasukuni; the shrine carried out checks and discovered that these names were not in the archive. The dead were duly transformed into kami through a rite of apotheosis. [2]

The Repository (courtesy of Yasukuni Shrine)

A second point to make is that Yasukuni is a place of intimate personal memory. Many of the war veterans interviewed by this author related that they went to Yasukuni every year on the anniversary of a comrade — again perhaps at the spring or autumn festival — to keep alive personal memories, to keep the promise they made to meet again at Yasukuni — and to pray for peace. [3]

Notes

[1] The best discussion of the political dimension to the Yasukuni problem, with which this article does not engage, is to be found in John Nelson ( 2003), “Social Memory as Ritual Practice: Commemorating Spirits of the Military Dead at Yasukuni Shinto Shrine,” Journal of Asian Studies 62, 2.

[2] For a fuller discussion of the rites of apotheosis, and of propitiation, see John Breen (2004), ‘The dead and the living in the land of peace: a sociology of Yasukuni shrine’ in John Breen ed., Death in Japan (Mortality [special issue]) 9, 1, pp. 77-82.

[3] For veterans and their views on Yasukuni, see Breen (2004), ‘The dead and the living’, pp. 88-90.