Pan-Korean Nationalism, Anti-Great Power-ism and U.S.-South Korean Relations Available in Korean Translation and French Translation

By Jiyul Kim

The overwhelming attention accorded the North Korean nuclear issue seems to have precluded a close examination of the U.S. – South Korean relationship as it enters a profound transitional period. [1] Current internal trends and dynamics in South Korean politics will require a fundamental reassessment of that relation. A major change in the character of the alliance, especially its military dimensions, is in the offing. However, such a change need not be seen as detrimental to the U.S.

New Ideologies of Korean Identity

Two major ideological trends gaining momentum in South Korea, pan-Korean nationalism and anti-Great Power-ism, will result in a significant shift in the locus of political interest and power. These are not new, but what makes them particularly powerful today is the impact of a generational shift and the phenomenon of what Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter term “Ruptured History” that arose as a result of the end of the Cold War and democratization, both of which occurred almost simultaneously for South Korea in the late 1980s.[2]

Pan-Korean nationalism and anti-Great Power-ism are closely associated with changing notions of identity and nationalism. These are ideological forces that are driven by cultural factors such as the symbolism of historical experience or, more precisely, memory of that history. What is happening in contemporary South Korean politics is a struggle that is as much over the past as it is about the future.

Pan Korean nationalism is the term I use to describe the sense of Korean nationalism in South Korea that embraces north and south. Anti-Great Power-ism refers to the desire of Koreans to escape from the sort of Great Power exploitation and victimization, actual and perceived, that the Korean peninsula has experienced since the latter half of the 19th century. These two ideas are closely linked, but how that linkage is conceptualized and given political expression, based on how history is remembered and should be rectified, has resulted in a deep division between the young and the old. The most important generational divide is between those who remember the Korean War and those who do not.

The young tend to imagine and invoke an understanding of the post Korean War situation on the peninsula that is a product of the post Cold War status quo in which North Korea is no longer the evil aggressor, but an equal victim of Great Power politics. This has led to a new terminology, “South-South Conflict” (nam-nam kaltung) that describes the deep division and disunity that now exists between the young, many of whom would embrace and help the North, and the old, who hew to the anti-Communist anti-North Korea line that took root during the Korean War. To be sure there are exceptions, for example, the recent appearance of the New Right that is comprised of young South Koreans who reject both the left as anti-democratic and anti-capitalist and the traditional right as corrupt. But such exceptions still remain politically small and relatively marginalized.[3]

South Korea is therefore in a transitional period. The post-Korean War generation has matured and is poised to assume political leadership. In many ways the election of Roh Mu-hyon as President in 2002 was the first step in this transition. Above all they reject the previous political paradigm that had functioned under the aegis of the Cold War and was based on intimate ties to the United States. They seek to realize the long held dream of achieving self-determination, a Korea that is master of its own fate and destiny, a destiny that promises greatness. In their eyes, such a destiny can only be predicated on peaceful reunification.

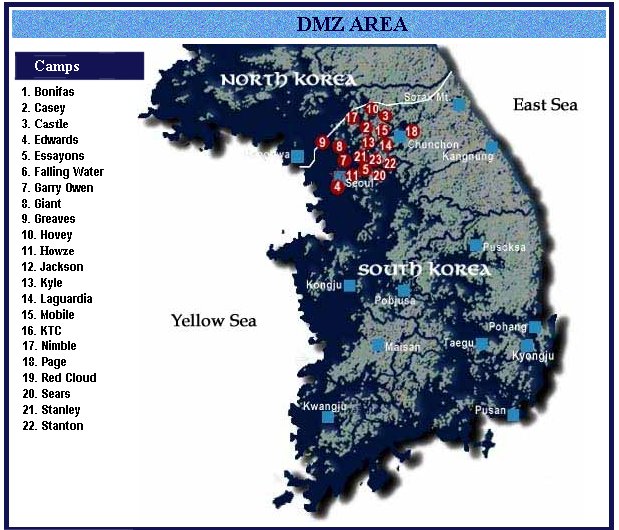

U.S. Bases in South Korea

Pan-Korean Nationalism

The end of the Cold War unleashed forces that have led to the rise of profoundly altered forms of nationalism throughout East Asia. Resurgent and rediscovered memories and interpretations of the past suppressed by Cold War politics in China, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and Taiwan, the key players of the Cold War in Asia, have resulted in defining a clearer and perhaps a more powerful image of themselves as a people and a nation. This new nationalism has also had a powerful effect not only on relationships among them, but especially with the United States, because of its dominant role in defeating Japan in World War II and throughout the Cold War. Few if any American decision-makers and scholars appreciate the depth and breadth of this transformation that will undoubtedly have profound impact on U.S. relations with East Asia. Just as 1945 ruptured the previous flow of history and ushered in a new world order, the end of the Cold War has produced a fundamental historical rupture that is now generating a new logic of national identity and new international relationships.[4] Certainly globalization is part of the new calculus, but perhaps just as important is this new form of East Asian nationalism. The paradox of the post Cold War world is that it has created a more interconnected world through globalization, but it has simultaneously energized particularistic and inward-oriented nationalisms based on ethnic, religious, and other cultural foundations.

What is remarkable for East Asia is that the struggle for resolution, the path toward framing the new world order is as much a struggle over history as it is a struggle over the future. Democratization in such places as South Korea and Taiwan has made it possible for history that had been repressed and suppressed during the Cold War to open to public discussion and debate. The emotional fervor with which public debate over the past has surfaced in South Korea today, notably but not exclusively over the period of Japanese colonialism and the role of the U.S. throughout modern Korean history during the Korean War and the period of authoritarian rule from the 1960s to the mid 1980s, is something that Americans would do well to appreciate. It is no accident that President Roh Mu-hyon focused on the theme of “cleansing history” in his Liberation Day speech in August 2004 and again in 2005.[5] To Roh and many of his colleagues, the history of Great Power rivalry and conflict over Korea is the primary source of Korea’s woes including colonization, division, war, distorted modernity and development, and, perhaps most of all, the power to determine its own course and destiny. The result, as popularly perceived, was immeasurable suffering of the Korean people as victims of colonization, wars, and crimes by occupation soldiers, and as proxy soldiers in Vietnam trading blood for material gains.

The primary agency of Korea’s past and contemporary predicaments are thus viewed as foreign not domestic, and external not internal. The Korean people’s century of oppression and subjugation first under the Great Power power-plays of the late 19th century followed by 40 years of Japanese colonization, and then trapped in the polemics and conflicts of the Cold War under authoritarian and dictatorial rulers, has created immense pressure to seek resolution to history’s exploitation, injustice and victimization. Comprehending the political consequences of this force is crucial to understanding South Korea‘s future, the future of the Korean peninsula, and of the U.S.-South Korean relationship.

On September 15th this year, the 55th anniversary of the Inch’on landing that turned the tide of the Korean War, a simmering dispute over a relatively innocuous statue of General MacArthur in Inch’on exploded in violent confrontation between 4,000 South Koreans who wanted the statue removed and 4,000 riot police supported by a thousand citizen supporters of the statue. The movement to remove MacArthur’s statue that began this spring as a small citizen’s campaign escalated into a symbolic battle between the new and the old generations. The anti-MacArthur movement is a branch of the larger anti-American movement that has identified the statue as embodying one of the greatest American betrayals of Korea. One leader of the movement explained the rationale this way: “it is time to reappraise MacArthur’s role in history. If it were not for him, our country would not have been colonized and divided as it was.” In effect some members of the anti-MacArthur group apparently would believe that unification under North Korea would have been a good thing and that it was tragically thwarted by U.S. interference.[6] Such a stance is also, of course, a fundamental challenge to the legitimacy of the South Korean state that these critics see as essentially a colony of the American Cold War empire. Although this view is still in the minority, the ambiguous standing of the ruling Uri party indicates a leaning toward supporting that revisionist view. This is but the latest public demonstration of growing anti-Americanism that the U.S. Congress has found so disturbing that it sent a letter of protest to President Roh with an offer to move the statue to a place of honor in Washington.[7]

Protecting the MacArthur statue from demonstrators

Anti-Great Power-ism

South Korea’s anti-American consciousness is growing. Although it had existed in the Cold War years, this sentiment, especially among the younger post-Korean War generation, became very public with the revelations over charges of deliberate killing of civilians by U.S. forces at Nogun-ri and many other places during the Korean War. The death of two young girls who were run over and killed by an American tracked vehicle during an exercise in 2002 led to massive demonstrations in which American flags were burned. In the wake of such graphic demonstrations of what was perceived in the U.S. Congress as ingratitude by the Korean people, Congress ignored a resolution to mark the 50th anniversary of the US-South Korea Mutual Security Treaty in 2003 while passing resolutions to recognize the 150th anniversary of US-Japan diplomatic ties since 1853 and the 25th anniversary of the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979. This Congressional rebuff received scant attention in South Korea.[8]

Anti-Americanism is but a part of a larger cultural force that might be called anti-Great Power-ism whose roots can be traced to the mid 19th century if not earlier. Soon after the Opium Wars, Korea was drawn into the Great Power game over East Asia. This is the origin in Korean historiography and in popular memory of over a century of Korean victimization by the Great Powers. Japan’s place in this narrative looms large not only because she was the first to force Korea open in 1876, opening two new treaty ports and claiming extraterritoriality by means of gunboat diplomacy, but more vividly because of the legacies of the four decades of colonialism. Anti-Japanism, which had been largely suppressed during the Cold War, blossomed with the historical rupture marking the end of the Cold War as issues concerning the oppression of the military comfort women and Korean slave labor erupted into public confrontation and successive court cases.

When the Japanese ambassador stated in February 2005 that Tokdo/Takeshima island in the East Sea/Sea of Japan was sovereign Japanese territory, he unleashed a massive and pervasive wave of citizen level anti-Japan activism that made a mockery of the official bilateral declaration of 2005 as the year of Japanese-Korean Friendship.[9] A recent poll taken in late August and early September by the Chung’ang ilbo national daily showed that an astonishing 62% of Koreans hated Japan. North Korea received 9% while the U.S. received 14%. A poll by the Han’guk ilbo national daily and the Yomiuri Japanese daily in May showed that 57.2% of Koreans saw Japan as a military threat while only 6.2% of the Japanese felt that way about South Korea. Yomiuri’s reporting on the same poll highlighted even more disturbing figures. A record 90% of South Koreans said they distrusted Japan and 89% thought bilateral ties were negative. In contrast 59% of Japanese said they trusted South Korea and 60% thought bilateral ties were positive. When asked about the factors that contributed to a negative relationship, 94% of the South Koreans and 65% of the Japanese cited the Tokdo/Takeshima issue.[10] One perhaps tragic irony of this is that the enormous surge of South Korean popular culture in Japan, especially movies, dramas and singers, have made Japanese the largest tourist group in South Korea. Thus the streets of Seoul and other key tourist destinations specialize in catering to Japanese visitors at a time of rising Korean antagonisms toward Japan. Fortunately anti-Japanism has not translated into violent action, but the sentiments are deep and strong and animated by long standing issues over colonial compensation especially over forced labor, comfort women and atom bomb victims,[11] the protection, privileged positions and aggrandizement by collaborators, the never ending dispute over Japanese history text books, the controversy over the Japanese Prime Minister’s visits to Yasukuni Shrine, and most recently, over the Tokdo/Takeshima island sovereignty issue.

Anti-Japanese demonstration in South Korea

Even the memory of Park Chung Hee, the ironhanded President for most of the 1960s and 70s who is widely credited as the man most responsible for South Korea’s economic transformation, is tainted by his service to imperial Japan as a schoolteacher and an Army officer. The anti-Park movement has reached some absurd but highly symbolic actions such as the decision earlier this year to remove his calligraphy on the sign board of Kwanghwamun, the political-cultural heart of Seoul and replace it with a mosaic of characters written by a Choso�n dynasty king whose nationalist credentials are presumably less contested.[12]

Examples of anger directed toward the U.S. extend across the long twentieth century, but it is only in the post-Cold War era that the issues have come to the fore. Here, too, there is a long history of grievances. One of the results of Theodore Roosevelt’s mediation of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 was the secret Taft-Katsura agreement whereby the U.S. and Japan mutually recognized each other’s primacy of interest in Korea and the Philippines respectively. This made possible the Protectorate Treaty that made Korea a Japanese colony in 1905. The liberation that came with the defeat of Japan in 1945 is now remembered by many for the U.S. suppression of left nationalist movements in the American zone and the sealing of a de facto permanent division of the peninsula.

It should be noted that after decades of denying leftist nationalists recognition as independence fighters, South Korea this year decided to recognize and honor them, although a proposal to include Kim Il Sung in that group was voted down.[13] The Korean War, the greatest tragedy in modern Korean history, is now widely interpreted as a proxy war between the U.S. on the one hand, and the Soviet Union and China on the other. In this view, the Korean people, north and south, were merely the pawns and victims of a disastrous war. Even before the Korean War, American involvement is read into the bloody suppression of the Cheju uprising in the spring of 1948. The perceived betrayals of the Cold War continued with the U.S. tolerance, acceptance and support for successive authoritarian and dictatorial regimes. Park Chung Hee’s coup of 1961 that overturned a democratic regime less than a year old, whatever initial American anxiety, was quickly supported.

South Korea’s large-scale support for the Vietnam War, maintaining a force of 50,000, by far the largest non-U.S. force in the war, is now seen by many as a devil’s deal to trade blood for money and materiel. The normalization treaty with Japan in 1965, a measure increasingly seen as a humiliating compact that signed away the people’s right to seek just redress and compensation for colonial suffering, was concluded under American pressure on the Japanese and the Koreans. When President Nixon visited mainland China in 1972, the shock and sense of betrayal in South Korea (as well as Japan), was nearly overwhelming. Almost overnight, a staunch Cold War ally of the United States and the free world, Taiwan, was left out in the cold while Japan and Korea were notified of the grand strategic shift only after the fact. The sense of America’s betrayal of its allies in Asia was further reinforced by the perceived betrayal of South Vietnam which was forced to accept, in late 1972, the Paris Peace Accords and the decision by Nixon, under the newly declared Guam Doctrine, to withdraw nearly half of American ground forces in South Korea around the same time. President Chun Doo Hwan’s visit as the first head of state to visit the new Reagan White House in 1981, less than a year after his bloody suppression of the Kwangju people’s democratic uprising in May 1980, a searing incident that some connect with U.S. complicity and support, and Chun’s coup in December 1980, is seen by many as a cynical U.S. policy that belied the rhetoric of promoting freedom and democracy.

The latest in this series of perceived American betrayals of the Korean people, and the start of the current wave of anti-American activism, began with the abrupt change in policy toward North Korea when George Bush entered the White House in 2001. The year 2000 had been a banner year in fulfilling hopes of unification. President Kim Dae-jung, propelled by his popular Sunshine Policy, made a triumphal visit to Pyongyang in June. Secretary of State Albright followed in the fall and there were credible rumors of a North Korea visit by President Clinton.

That promise and dream were, in the Korean people’s minds, dashed by the Bush administration that immediately placed North Korea policy on hold for 6 months and later made it clear that it would treat North Korea with suspicion, distrust and even hostility, proclaiming it a member of the “Axis of Evil”, thus in effect targeting the regime for overthrow. The end of the Cold War and Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy had implanted in the South Korean people’s hearts the possibility of imagining and even living in the post Korean War epoch. The Post Korean War can be seen as emblematic of the view that the North should no longer be seen as an enemy, the perpetrator of the Korean War, but as a brother to be embraced and helped. The end of the Cold War, a confidence born of South Korea’s rise as a regional power that contrasted dramatically with North Korea’s demise as well as the improving political situation during the Kim Dae-jung and Clinton administrations, made the concept of a unified Korea and the notion of pan Korean nationalism something achievable and tangible.

Anti-Bush demonstration in South Korea

The reason why the year 2005 has assumed such symbolic significance is that it marks the convergence of the anniversaries of three key events: the 100th of the Japanese Protectorate Treaty, the 60th of the Liberation and division of Korea, and the 40th of the normalization treaty with Japan.

These events highlight the dominant historical memory and forces that animate the new political trends and fault lines, anti-Japanism, anti-Americanism, and pan Korean nationalism. It is a credit to the maturity of South Korean democracy, perhaps the most vibrant democracy in East Asia, that the debate and discourse over these contentious issues is being conducted in the public arena, indeed, sometimes resulting in physical confrontation.

Following up on President Roh Mu-hyon’s call for “cleansing history” in his August 2004 speech, the National Assembly in December passed a series of bills that formed a number of Truth Committees that would examine a number of key historical issues from the colonial period as well as the era of military rule that lasted from 1961 to the late 1980s.[14] It is striking that the most contentious issues in the debate have thus far focused not on the U.S. but on Japan, specifically the issues of forced laborers and comfort women.

Domestically the focus is to be on colonial era collaborators and the human rights record of the military regimes. The two are intimately linked especially through Park Chung Hee, who provides a direct conceptual bridge between collaboration and human rights abuses of the military regimes. This has political ramifications since Park’s daughter, Assemblywomen Park Kun-hye, is the leader of the conservative Grand National Party and a leading presidential candidate for the 2007 elections. Park Kun-hye’s struggle is thus not only over her vision for South Korea’s future, but also over the historical memory of her father, symbol for some of subordination to a conquering Japan and others as the father of Korean development.

Some have likened the Truth Committees, which have reopened old raw wounds in the Korean psyche, with the truth and reconciliation process in South Africa. Perhaps it will result in finally burying the past, but such an outcome is doubtful. The private Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities (minjok munje yonguso) has vowed to publish a comprehensive list of collaborators by the end of 2007.[15]

Their goal is not only to discredit collaborators, many of whom played prominent roles in South Korea’s development especially as politicians, businessmen and military leaders, but also to deny their descendents the opportunity to enjoy what are seen as ill-gotten material gains from that collaboration such as the residual wealth and land accumulated from business and colonial government positions. The place in history and society of many of these people is so wide ranging that it threatens to cause a major earthquake along political fault lines. Many South Koreans are aware of North Korea’s early purging of “collaborators” in the years before the Korean War. From this perspective, South Korea is thus seen by proponents of the cleansing as being nearly 60 years behind in this vital task to reclaim a pure Korean identity.

Transformation of U.S.-South Korean Relations

What are the implications of this tumultuous period for the future of U.S.-South Korean relations and the alliance? The post World War II U.S. entry into Korea, the decision to divide the peninsula, U.S. intervention in the Korean War, and the continued presence of U.S. forces six decades after “independence” are products of the Cold War. The question is: what is the U.S. role in a post Cold War Korea.

Nearly a century ago President Wilson exhilarated the subjugated people of the world with his idealistic vision of freedom and self-determination for all people. An increasing number of South Koreans now believe that they can achieve that self-determination and eventually create a unified Korea that can chart its own path. There is an increasingly powerful view that the time has come for South Korea to transcend its colonial and Cold War past and enter the post-Korean War epoch by realizing the long cherished dream of a unified Korea free from victimization of the Great Powers. The overarching ideology is the notion of a National Restoration (minjok chunghung) a concept and term that has its roots in the colonial period and in particular with Park Chung Hee in the early 1960s.[16]

The current U.S. national security strategy is rooted in three principal national interests: homeland defense, economic prosperity and promotion of democracy. None of the three interests requires a bilateral U.S.-Korea mutual security treaty and a military alliance rooted in an American military presence in South Korea. The American strategic requirement to establish expeditionary bases ready to respond flexibly to contingencies around the world will not be jeopardized if U.S. military forces are not stationed in South Korea since the U.S. military will surely remain anchored in Japan, Guam and throughout the Pacific. Indeed, President Roh Mu-hyon’s statement earlier this year suggesting that South Korea would not support the deployment of U.S. forces in Korea to engage in regional conflicts indicates that it may be disadvantageous to seek to maintain a large military presence in South Korea. While the possibility of a U.S. military withdrawal from South Korea is nearly unthinkable to many analysts, such an action need not be equated with the ending of the alliance or the very important economic relationship. The most recent polls indicate that over the last few years the number of South Koreans favoring the withdrawal of U.S. forces has steadily increased to the point where it seems to constitute the majority.[17] Under the circumstances, arguably, removing this irritant in U.S.-Korea relations could provide a firmer basis for their economic and strategic relationship.

If South Korea desires the reduction or even the elimination of a U.S. military presence, then it behooves us to oversee the repositioning of those forces under our terms and our control. The recent U.S. initiated agreements to draw down U.S. Forces Korea from 37,000 to 25,000 and consolidate U.S. forces to bases south of the Han River could be a promising initiative toward redefining the security relationship, even if some South Koreans interpret the move as a U.S. ruse to launch a pre-emptive attack on the North.[18] We should not be apprehensive about completing the process if that is what the South Korean people want. It is even possible to imagine a U.S. pullout as facilitating the unification of the Koreas that can contribute toward overcoming the North Korean conundrum as the perennial security challenge of the region. This can come about through a change in China’s perception that a unified Korea without U.S. military presence, a unified Korea that is fiercely independent, could actually provide a better buffer state than North Korea. China holds the trump card on unification by the sheer fact that it alone insures the existence of North Korea. It also enjoys good relations with South Korea. The possibility of a more stable northeast Asia based on a balance between a continental bloc consisting of China and a China-leaning unified Korea on the one hand, and a maritime bloc anchored on the U.S.-Japan alliance on the other, is perhaps an outcome to be welcomed.[19]

In conclusion, South Korean politics is in a profound period of transition as the result of a generational shift, the end of the Cold War, democratization, and growing self-confidence. Among the emerging political forces, those that are creating the most important political fault lines are the ideologies of pan-Korean nationalism and anti-Great Power-ism. These trends could well mark the end of the U.S. – South Korean alliance as we know it. Most importantly, such an outcome, which could eventually lead to a complete U.S. military pull out, need not mean the end of a close relationship between the two nations. Indeed, it could very well resolve some of the thorniest security issues in the region. Above all, we can take comfort in knowing that such maturation of South Korea and of the Korean peninsula could fulfill not only the long held Wilsonian ideal of a world organized on principles of self-determination, but also encourage the spread of democratization and freedom in step with realization of the principle of self-determination. It is an outcome to be welcomed not feared.

Colonel Jiyul Kim is the Director of Asian Studies at the U.S. Army War College. This article does not represent the views and policies of the U.S. Government, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Army. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted December 13, 2005.

NOTES

1. I am indebted to Sheila Miyoshi Jager of Oberlin College, who has been my principal intellectual partner and sounding board for more than a decade especially on issues dealing with Korea. Many of the points I raise in this article derive directly from our joint effort and as such are as much hers as they are mine. See the following Japan Focus articles on related issues: “Korean Collaborators: South Korea’s Truth Committees and the Forging of a New Pan-Korean Nationalism”;“Rewriting the Past/ Re-Claiming the Future: Nationalism and the Politics of Anti-Americanism in South Korea.”

2. Sheila Miyoshi Jager and Rana Mitter, Ruptured Histories: War, Memory and the Post-Cold War in Asia, forthcoming, Harvard University Press.

3. The New Right seems to be a growing political movement although it has the potential to change the South Korean political landscape by creating a third alternative through the creation of a new political current consisting of an alliance between moderate conservatives from the left and moderate reformers from the right. For background see Kim So Young, “Korea: New Conservative Groups Band Against Roh, Uri Party,” The Korea Herald, November 30, 2004.

4. The discussion here is based largely on the previously mentioned Jager-Mitter volume Ruptured Histories.

5. The official English transcript of the 2004 speech is available at the official web site of the Office of the President: a version of the 2005 speech with a short summary is available.

6. Donald Kirk, “Korea’s Generational Clash: A statue of Gen. MacArthur has drawn fire from leftists and support from war vets,” The Christian Science Monitor, August 8, 2005. Barbara Demick, “MacArthur Is Back in the Heat of Battle,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 2005. “What Is the Ruling Party’s Position on the Incheon Landing?” Digital Chosun, September 12, 2005.

7. Letter, from the Committee on International Relations, House of Representatives, to Roh Moo Hyun, September 15, 2005. Facsimile of the letter.

8. The resolution to mark the 150th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the United States and Japan is H.CON.RES.418 which passed the House on July 22, 2004 (text). The resolution marking the 25th anniversary of the Taiwan Relations Act is H.CON.RES.462 which passed the House on July 15, 2004. The resolutions for marking the 50th anniversary of the U.S.-ROK Mutual Defense Treaty is H.RES 385 ), introduced on October 1, 2003, and S.RES 256 (text), introduced on October 31, 2003 in the 108th Congress. See the one Korean story on this issue at “U.S. Congress Killed Korea Resolution,” Digital Chosun, March 25, 2005.

9. Kim Hyun, “Seoul Frowns at Tokyo Approach over Occupied Islets,” Yonhap NewsYonhap News, February 24, 2005. See also the following postings on Japan Focus that provide both South Korean and Japanese views on the Tokdo/Takeshima issue for insights into the historical and technical factors that have turned this into a symbolic issue corroding and distorting Japanese and South Korean views of each other: “Takeshima/Tokdo and the Roots of Japan-Korea Conflict,”, March 28, 2005; Kosuke Takahashi, “Japan-South Korea Ties on the Rocks,” March 28, 2005; Wada Haruki “A Plea to Resolve a Worsening Dispute,” , March 28, 2005; Lee Sang-tae, “Dokdo is Korean Territory,” July 28, 2005.

10. The Chung’ang ilbo poll was part of a national poll on wide ranging issues to mark the 40th anniversary of the newspaper and was conducted between August 24 and September 10, 2005. The results were published on September 22, 2005. Analysis and data in Korean of the political section of the poll is available.

An English summary of the major poll findings is available as “Majority Opposes U.S. Troop Presence,” September 22, 2005. The Han’guk ilbo – Yomiuri poll, to mark the 51st anniversary of the Han’guk ilbo, was conducted simultaneously in Korea and Japan to gauge each country’s perceptions and views of the other as well as on a number of key regional political issues. The Korean analyses of the results were published by the Han’guk ilbo on June 11, 2005. The Yomiuri discussion of the poll can be found at Japan Focus, “South Korean Mistrust of Japan: Poll,” June 10, 2005.

11. According to some estimates 20-30,000 of those killed or 10-20% of all immediate deaths from the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima were Koreans. There were about 50,000 Koreans in Hiroshima. Lisa Yoneyama, “Memory Matters: Hiroshima’s Korean Atom Bomb Memorial and the Politics of Ethnicity,” Public Culture 7.3, Spring 1995, p. 502. The memorial to Korean victims at Hiroshima cites 20,000 of the 200,000 killed were Koreans. In Nagasaki an estimated 10,000 of the population was Korean when the bomb was dropped. I have not been able to locate an accurate estimate of Korean dead, but one recent article infers “thousands.” Kathleen E. McLaughlin, “Foreign A-Bomb Victims are all but Forgotten,” San Francisco Chronicles, Aug 10, 2005. The relevant issue though is not so much those killed as Japanese government compensation of the survivors. See Andreas Hippin, “The end of silence: Korea’s Hiroshima, Korean A-bomb victims seek redress,” The Japan Times, August 2, 2005. This article (also available at Japan Focus) cites a Korean estimate of 50,000 killed and 80-120,000 second generation “victims” who should receive compensation.

12. The Kwanghwamun signboard story was first reported by the Han’gyore national daily newspaper on January 24, 2005 under the title “A Stain of Military Dictatorship, Kwanghwamun sign board to be changed” (kunsa tokje ui olluk, Kwanghwamun hyon’pan pakkwinda). The new signboard calligraphy is to be based on rubbings of characters written by King Chongjo (1776-1800).

13. Good overviews of the initiative to recognize leftist nationalists and actions taken to recognize 214 leftists at the 60th anniversary of liberation on August 15, 2005 are provided by Seo Dong-shin’s two articles in The Korea Times: “Independence Activists to Get Posthumous Honors,” The Korea Times, February 1, 2005, and “Leftist Independence Activists to Get Honors,” The Korea Times, August 3, 2005. The counterpart action to recognizing leftist nationalists is the civil movement to remove the tombs of “collaborators” from national cemeteries where they are honored as patriots. See for example Yang Hui-sun, “Who are History’s Independence Fighters?” (Nuga yoksa ui toknip t’usainga?), OhmyNews.com, March 2, 2005. The “Kim Il Sung as independence fighter” controversy erupted when the preeminent historian and chairman of the national committee to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Korea’s liberation, Kang Man-gil, told reporters that he saw Kim Il Sung’s anti-Japanese guerilla activities as part of the independence movement. Prof. Han Hong-gu of Sungkonghoe University and a member of the government mandated history Truth Committee (see note 13) had written in 2004 that Kim Il Sung was a “20th century nationalist.” See “Kim Il-sung a Freedom Fighter, Committee Chair Says,” Digital Chosun, April 11, 2005, and Seo Dong-shin, “Kim Il-sung Legacy Controversial in S. Korea,” The Korea Times, July 8, 2005.

14. Norimitsu Onishi, “Korea’s Tricky Task: Digging Up Past Treachery,” The New York Times, January 5, 2005. “S. Korea’s Spy Agency Picks 7 Cases for Reinvestigation,” Yonhap, February 3, 2005.

15. The Institute’s web site provides a comprehensive look at the movement and the efforts to unearth collaborators in South Korea (http://www.banmin.or.kr/). The collaborator list that began in 2001 is due for completion and publication in December 2007. Details of the project such as background, purpose, timeline, and committee members can be found under the “Directory of Collaborators” (ch’inil inmyong sajon) tab.

16. I am indebted to Bruce Cumings for pointing out the colonial origins of this term.

17. The most recent results are from the August-September 2005 Chung’ang ilbo poll referenced in note 11. It showed that 54% of the respondents wanted U.S. forces to depart while 30% wanted them to stay “for a considerable period of time” and only 16% favored a permanent presence.

18. This is of course absurd.

19. The conception here of a regional bipolar balance was first suggested by Robert Ross (“The Geography of the Peace: East Asia in the Twenty-first Century,” International Security, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Spring 1999), 81-118). I developed this notion further in my study of the long range security implications of certain key factors and trends in Northeast Asia (“Continuity and Transformation in Northeast Asia and the End of American Exceptionalism: A Long-Range Outlook and US Policy Implications,” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, Vol. 13, No. 1 (Autumn 2001), 229-261.