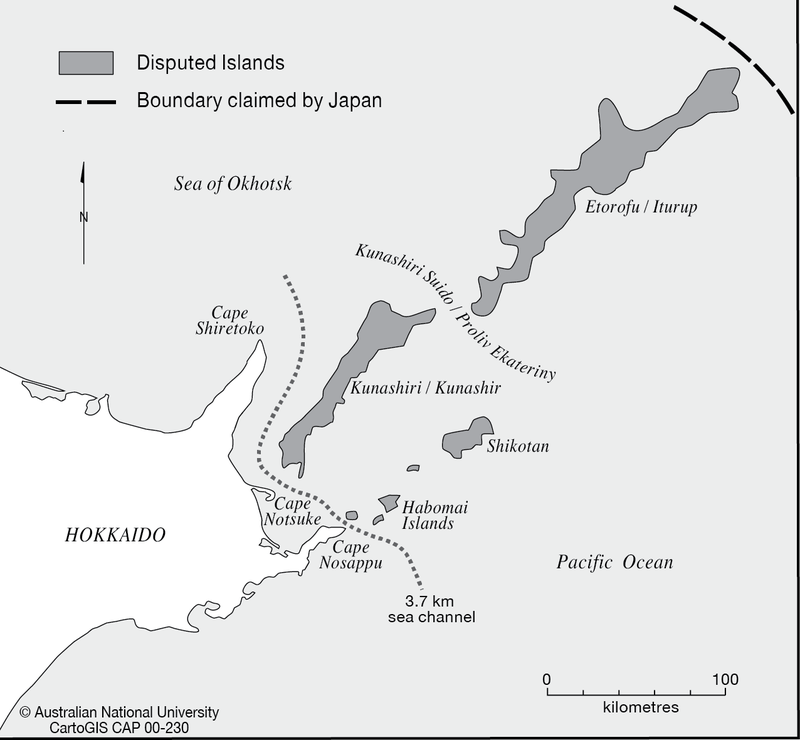

The territorial dispute between Russia and Japan over the Southern Kurils/Northern Territories has long been in a state of impasse. In simple terms, while Russia has conceded to transfer the islands of Shikotan and Habomai after the conclusion of a peace treaty, Japan insists that its sovereignty over all four of the disputed islands be recognised. Despite lengthy bilateral negotiations over seven decades and numerous imaginative proposals by academics and diplomats, the two sides have been unable to break this deadlock.

Seemingly unperturbed by the lack of meaningful progress achieved by his predecessors, Prime Minister Abe has been proactive in pursuing a territorial deal with Russia. In particular, it has become something of a mantra of his to state that “During my time in office, I will do everything possible to resolve the territorial problem.”[Kimura, 2015]. His specific plan is to offer that, if Russia acknowledges Japan’s sovereignty over the territory, he will respond with maximum flexibility with regard to the timing and manner of the islands’ actual return. In return for accepting this deal, Russia would be provided with generous assistance in the economic development of Siberia and the Russian Far East. The Japanese leader’s strategy for achieving this goal has been straightforward. Viewing President Putin as a politician with the power and willingness to settle the dispute, Prime Minister Abe has set about trying to meet with him as frequently as possible. This he succeeded in doing five times within little more than a year after his return to government in December 2012. Most striking in this regard was Abe’s official visit to Moscow in April 2013, the first by a Japanese leader in over a decade, as well as his appearance at the opening ceremony of the Sochi Olympics in February 2014, an event shunned by most Western leaders.

After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the rapprochement stalled as Japan felt obliged to follow the United States in introducing sanctions (albeit toothless ones). Nonetheless, Abe continued to hold meetings with Putin on the margins of international conferences, such as at ASEM in Milan (October 2014), APEC in Beijing (November 2014), and (as seems likely) the UN General Assembly in New York (September 2015). The Japanese prime minister also refused to abandon his intention of hosting the Russian president on an official visit to Tokyo, telling G7 counterparts in June 2015 of his need to continue high-level contacts with President Putin in order to achieve a territorial breakthrough [Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 2015].

And yet, despite these committed efforts by the Japanese leader and his resolute belief that Japan can still achieve a favourable outcome, there is a growing body of evidence that the Russian side is becoming ever more uncompromising. In particular, there are strong grounds to believe that Russia is now moving inexorably towards the point at which it will no longer even consider relinquishing the two smaller islands.

Map of the disputed islands (Source: CartoGIS, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University) |

The offer of two

As those familiar with this dispute will be aware, the proposal to return two islands originates from the 1956 Soviet-Japanese Joint Declaration. In the absence of a peace treaty, this was the document that officially ended the state of war between the countries and restored diplomatic relations. Although there was a failure to settle the territorial dispute at that time, not least because of US opposition, the Soviet Union offered “to transfer to Japan the Habomai Islands and the island of Shikotan, the actual transfer of these islands to Japan to take place after the conclusion of a Peace Treaty” [University of Tokyo, 1956

Although officially agreed upon in 1956, Moscow has not considered this proposal to be in effect for the majority of the time since. In fact, as early as 1960, General Secretary Khrushchev rescinded the offer in retaliation for the renewal of the US-Japan Security Treaty. This was how things stayed for the remainder of the Cold War with the Soviet Union adopting the position that there was no territorial dispute with Japan and that claims to the contrary were mere inventions by Japanese rightists.

In 1991, President Gorbachev finally acknowledged the existence of a territorial dispute. He refused, however, to recognise the validity of the 1956 Joint Declaration, saying that it had been “removed by history” [Sarkisov, 2009]. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, President Yeltsin went somewhat further but he was only willing to acknowledge the Joint Declaration indirectly. This was done via the 1993 Tokyo Declaration, which states that territorial negotiations will be “based on the documents produced with the two countries’ agreement”[MOFA, 1993]. President Putin is therefore the only Soviet/Russian leader since Khrushchev to have formally recognised the validity of the 1956 Joint Declaration, and thereby committed himself to transfer Habomai and Shikotan after the conclusion of a peace treaty. This he did in 2001 by signing the Irkutsk Statement. He has since reaffirmed this position on several subsequent occasions. There are strong signs, however, that this commitment may now once again be abandoned and that Russia may return to its pre-Putin, if not its pre-Gorbachev, policy.

Not even two?

The most obvious indication of the hardening of Russia’s position is the increased profile and frequency of official visits to the disputed territory. In particular, Prime Minister Medvedev made his third trip to the islands in August 2015, calling upon his fellow ministers to do likewise every three months. This they have dutifully done, with the agriculture and transport ministers following him to the islands in September. Perhaps the most striking ministerial visit of recent months, however, was that by Veronika Skvortsova in July. This is not because of the profile of the politician (she is health minister), but rather because she did not travel to Kunashir/i or Iturup/Etorofu like the others but instead visited Shikotan. It is also notable that the purpose of her visit was to open a new hospital. This is just one of a series of recently completed infrastructure projects on the islands and a further 70 billion roubles has been allocated for 2016-2025. The central authorities have also just unveiled a policy under which unused land in the Far East will be distributed to Russian citizens. The aim is to encourage economic development and the scheme will apply to the disputed islands. Lastly, in July 2015 Russia’s Minister for Far Eastern Development announced plans to increase the number of people living on all of the inhabited Kuril Islands to as high as 24,000 [Kuz’min, 2015]. Evidently, the fact that all of these new schemes extend, not only to Kunashir/i and Iturup/Etorofu, but also to Shikotan does not give encouragement to the idea that Russia is willing to uphold its 1956 commitment.

New hospital on Shikotan (Source) |

Confirmation of this trend can be found in Russian rhetoric. In particular, at the start of September Deputy Foreign Minister Morgulov told the press, “We are not engaging in any form of dialogue with Japan on the ‘Kuril problem’. This question was solved 70 years ago” [Interfax, 2015]. It is significant that this statement came from Morgulov since it was he who was engaged in peace treaty consultations with Japan in 2013-14. He is, however, far from being the only prominent figure to make such claims of late. For example, when asked last year about the prospects of resolving the territorial problem with Japan, Foreign Minister Lavrov replied bluntly that “Russia does not consider this situation to be a territorial dispute” [MID, 2014]. Prominent Russian Japan specialists, who would once have taken a more sympathetic view, have also become dismissive of Japan’s claims. For instance, Viktor Pavlyatenko of the Russian Academy of Sciences states: “My fundamental view is that we have no territorial dispute with Japan.” Rather, Moscow’s acknowledgement of the existence of a territorial dispute was an error committed when the country was weak and undergoing political turmoil. “At that time some ‘clumsy’ steps were taken on behalf of Russia with regard to Japanese demands. This began under Gorbachev and continued into the 1990s. There was a failure in our diplomacy in relation to Japan’s claims. It is now time to finish ‘cleaning up’.” [RIA Novosti, 2015].

This mode of thinking has been on the rise since before the Crimea crisis but it has since accelerated. Above all, while government ministers have generally been measured in their response to the introduction of Japanese sanctions, this has not been the case for other Russian politicians. Nowhere is this better illustrated that in the remarks of Leonid Kalashnikov, first deputy chairman of the Duma foreign affairs committee. Leaving no doubts as to his opposition to any territorial concessions, he stated:

“Japan’s chances have been restricted by themselves to the lowest possible level in connection with the fact that, having joined Western sanctions, they have now openly become an adversary or even an enemy of Russia. If prior to the sanctions there was some logic in holding negotiations, there is not now.” [Lenta, 2015

Prospects?

Giventhese significant developments , it appears likely that relatively soon Russia will formally revoke its offer to transfer even the two smaller islands. This would surely further damage the prospects of signing a peace treaty, yet there are indications that the Kremlin is increasingly indifferent on this point. In particular, Presidential Chief of Staff Sergei Ivanov has said that he does not regard a peace treaty as especially necessary [IISS, 2011]. In fact, there are signs that considerable thought has already gone into calculating how this abrogation could best be achieved. One option is to blame Khrushchev. This argument has been rehearsed in Rossiiskaya Gazeta, the government newspaper, where it has been stated that his offer of two islands was “short-sighted and personal” and counter to “the international legal basis of the Yalta and Potsdam Agreements” [Sabov, 2005]. This criticism also coincides neatly with the popular denunciation of his decision to transfer Crimea to Ukraine in 1954. Rejection of the 1956 Joint Declaration could therefore be presented as correcting another of Khrushchev’s reckless decisions. An alternative proposal has been to claim that the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea represents a “fundamental change of circumstances” since it introduced the principle of the 200-mile exclusive economic zone. This is seen as a plausible excuse by some since the Vienna Convention cites a “fundamental change in circumstances” as potentially legitimate grounds for terminating a treaty.

Whatever the fig leaf used, it seems only a matter of time before the renunciation comes. This is likely to be accompanied by the discontinuation of the visa-free visits that enable Japanese former residents and their relatives to travel to the islands. Indeed, it seems that this programme is already in danger since Russia has recently cancelled several of these planned trips [Yomiuri Shinbun, 2015]. These changes may well occur during the remaining years of Putin’s leadership, but, if not, it is highly likely that the next Russian president will not commit himself/herself to the transfer of Shikotan and Habomai. This successor is almost certain to be weaker than Putin and therefore prone to eschew unpopular foreign-policy positions. There is also every chance that Putin’s replacement will be more stridently nationalist. An indication of what such a figure’s attitude to the territorial dispute might be was given in August by Dmitrii Rogozin, Russia’s deputy prime minister. In response to Japanese complaints about Medvedev’s visit to Iturup/Etorofu, Rogozin took to Twitter to say of the Japanese, “If they were real men, they would follow tradition, commit hara-kiri and at last quiet down. All they’re doing is making noise” [Vedomosti, 2015].

Some might be inclined to think that all of this matters little since the Japanese government in 2015 has no intention of accepting the offer of only two islands. In fact, however, these recent developments are important because they demonstrate just how forlorn Japanese hopes are. While Prime Minister Abe is dreaming of using his strong personal ties with Putin to persuade the Russian leader to acknowledge Japanese sovereignty over all four islands, the Russian side is steadily progressing towards rejecting all compromise whatsoever.

Recommended citation: James D.J. Brown, “Not Even Two? New developments in the territorial dispute between Russia and Japan”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 13, Issue 38, No. 2, September 21, 2015.

Related articles

• John W. Dower, The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in U.S.-Japan-China Relations

• Kimie Hara, Untying the Kurillian Knot: Toward an Åland-Inspired Solution for the Russo-Japanese Territorial Dispute

• Tanaka Sakai, The Northern Territories Impasse, Russia and Japanese Dependence on the U.S.

Works Cited

IISS. (2011). The Shangri-La Dialogue Report. London: International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Interfax. (2015, September 2). V MID RF otkazalis’ vesti peregovory s Yaponiei po povodu Kuril [Russian Foreign Ministry refuses to hold negotiations with Japan regarding the Kurils].

Kimura, H. (2015, August 25). Hoppōryōdo henkan no ‘amenori’ o mate [Wait for ‘an opportunity from heaven’ for the return of the Northern Territories]. Sankei Shinbun.

Kuz’min, V. (2015, July 23). Vernut’ zhizn’ na ostrova [Return life to the islands]. Rossiiskaya Gazeta.

Lenta. (2015, February 7). V Gosdume posovetovali Tokio zabyt’ o nadezhdakh na ustupki po voprosu Kuril [In the State Duma they tell Tokyo to forget about hopes for concessions on the Kuril question].

MID. (2014, February 18). Ministerstvo Inostrannykh Del. Retrieved from Otvet S.V. Lavrova na vopros o rossiysko-yaponskom territorial’nom spore [Answer by S.V. Lavrov to a question about the Russian-Japanese territorial dispute].

MOFA. (1993, October 13). Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved from Tokyo Declaration on Japan-Russia Relations

RIA Novosti. (2015, August 12). Vostokoved: predlozheniye yaponskogo politika – obmen Kuril na ‘nichto’ [Orientalist: Offer of Japanese politician is to exchange the Kurils for ‘nothing’].

Rossiiskaya Gazeta. (2015, June 8). Sindzo Abe: Yaponii neobkhodim dialog s Rossiei na urovne liderov [Shinzo Abe: Japan needs dialogue with Russia at the leaders’ level]. Rossiiskaya Gazeta.

Sabov, A. (2005, October 28). Za Kurily. Istoriya ostrovov preduprezhdaet: Peregovory o ‘severnykh territoriyakh’ opasny dlya zdorov’ya natsii [For the Kurils. The history of the islands is a warning: Negotiations on the ‘Northern Territories’ is a danger to the health of the nation]. Rossiiskaya Gazeta.

Sarkisov, K. (2009). The territorial dispute between Japan and Russia: The ‘two island solution’ and Putin’s last years as President. In K. (. Sarkisov, Northern Territories, Asia-Pacific Regional Conflicts and the Åland Experience. Oxon: Routledge.

University of Tokyo. (1956). The World and Japan Database Project. Retrieved from Joint Declaration by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and Japan

Vedomosti. (2015, August 24). Rogozin predlozhil yapontsam sdelat’ kharakiri iz-za poseshcheniya Medvedevym Kuril [Rogozin suggests the Japanese commit hara-kiri following Medvedev’s visit to the Kurils].

Yomiuri Shinbun. (2015, September 2). Hoppōryōdo bosan chūshi, ‘teishutsu shorui, kon’nan’na shūsei yōkyū’ [Northern Territories grave visit cancelled, ‘difficult revisions to submitted documents requested’].