Sunset for Japanese Chip Makers? A new front in Japan-Korea and Japan-China Conflict

By Hisane MASAKI

[Japan has steadily lost its leading edge in computer memory chip production over the last decade. Its responses include its first attempts at tariff protection, bringing multiple cases before the WTO charging discrimination, and a series of new joint ventures seeking to regain the cutting edge.The consequences include rising tensions between Japan and other nations, including Korea, China and the US. In this comprehensive assessment, Masaki Hisane surveys recent trends and future prospects for Japan’s high tech industries. Japan Focus.]

TOKYO – Japan has decided to levy punitive import tariffs on computer memory chips made by South Korea’s Hynix Semiconductors Inc, providing the latest – and most symbolic – illustration of how life is getting difficult for once-dominant Japanese chips.

Acting on cries for help from domestic companies struggling with increasingly tough foreign competition, Japan has decided to slap countervailing tariffs of 27.2% on Hynix’s dynamic random access memory (DRAM) chips. The decision was formally endorsed at a regular meeting of Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s cabinet on January 24. The tariffs, which became effective on Jan.27, will remain in place for five years.

It marked the first time that Japan had applied punitive tariffs of that kind for any imports. It also became the first case of Japan slapping punitive import duties on high-technology products. Countervailing duties are punitive tariffs that an importing country imposes on an exporter that receives government subsidies.

In making a preliminary decision to levy punitive tariffs, the Japanese government said in October that it had notified South Korea that it might impose 27.2% countervailing tariffs on DRAM chips made by Hynix, one of the world’s leading memory-chip makers. The Japanese notification to South Korea came after more than a year of investigations into allegations from two domestic companies – Elpida Memory Inc and Micron Japan Ltd, a unit of US-based Micron Technology Inc – that Hynix exports are being subsidized by unfair loans from banks backed by the South Korean government.

The two companies claimed that imports of subsidized Hynix DRAM chips were being sold at unfairly low prices and were thereby hurting the Japanese chip industry. According to data from the South Korean Foreign Ministry, Hynix’s share of the Japanese DRAM market was 15.9% in 2004, trailing Samsung Electronics’ 38.3% and Elpida’s 18.6%. Before making the preliminary decision final, the Japanese government had allowed its South Korean counterpart and Hynix time to counter or disprove the Japanese allegations against the Korean chip maker in writing. But the preliminary decision was not reversed.

Hynix nearly collapsed under huge mountains of debt several years ago. It was saved twice – in 2001 and 2002 – by its creditor banks, which were majority-owned by the Korean government. The South Korean Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy has said in a statement, “The Japanese ruling is unreasonable and disappointing, as it is based on unilateral calls by Japanese semiconductor firms and has no legal basis.” Hynix has also said in a statement, “It is unfair for the Japanese government to regard the debt-restructuring plan as a government subsidy, because it is obvious that we raised funds to pay back the debt and gain creditor control.”

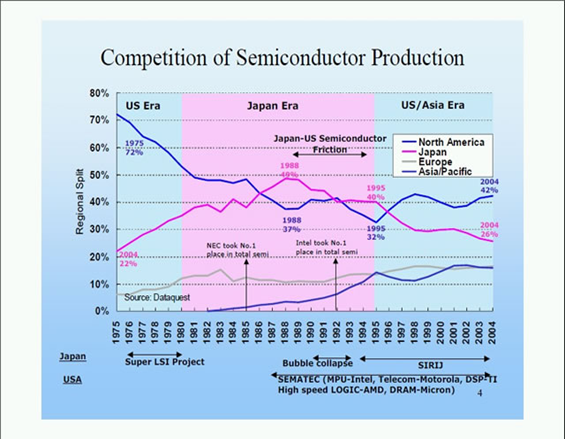

Japanese computer-chip makers now live in a totally different world from just a decade or so ago. Japanese semiconductors once dominated the world market, grabbing a combined global market share of more than 50% in the second half of the 1980s. Japanese products were proudly vaunted as Hinomaru chips (referring to Japan’s “rising sun” flag). But today, their global market share has plunged to about 20%. South Korean companies, including Samsung Electronics as well as Hynix, have emerged as key high-tech rivals to once-dominant Japanese companies, such as Toshiba in computer chips and Sony in consumer electronics.

Legal battles over chips

The Japanese decision to levy countervailing tariffs on Hynix products followed the imposition of such tariffs by the United States, in 2003, and the European Union, in 2004. The US tariff rates are 44% and the EU ones are 35%. South Korea has filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Geneva-based referee on trade disputes, against the US and EU measures, and is expected to take the case of Japan’s punitive tariffs to the WTO as well.

The trade body’s highest court, the Appellate Body, overturned an earlier ruling by a WTO dispute-settlement panel and handed down a verdict in favor of the US last June, emboldening Japan. In the case of the EU tariffs, however, the WTO ruled soon afterward that the 25-nation grouping should reconsider its measures as it had incorrectly calculated the material injury caused to its own products by the subsidies.

Elpida was formed in 1999 as a joint venture between electronics giants NEC and Hitachi. On the same day the Koizumi cabinet formally approved the punitive tariffs on Hynix, Elpida announced that it posted a 95% fall in quarterly net profit, hit by a slide in memory-chip prices. The company also now anticipates a full-year loss. For the year to March, Elpida reversed its net forecast to a loss in the range of 2 billion to 6 billion yen (US$17.4 million to $52.1 million) from a previous forecast of a profit of 5 billion to 10 billion yen.

Elpida is Japan’s only exclusive maker of DRAM chips, which are widely used in personal computers, as major Japanese electronics makers have pulled the plug on the DRAM business in recent years in the face of falling prices and intensifying competition in the sector. Hynix has been in a neck-and-neck race with Micron Technology of the US for the No 2 slot in the global DRAM chip market. Another South Korean chip maker, Samsung Electronics, has kept the position of market leader since 1993.

Hynix is also locked in legal disputes with Toshiba over patents on NAND flash memory chips used in digital cameras and MP3 players. Toshiba filed a lawsuit against Hynix with the Tokyo District Court in November 2004, seeking unspecified damages for violations of NAND-related patents and an injunction against the sale of the “infringed products”. At the time Toshiba filed a similar suit with a US court against Hynix and its US subsidiaries over their alleged infringements on patents related to NAND chips as well as DRAM chips.

NAND chips: Another bone of contention

More recently, Toshiba filed a complaint with the US International Trade Commission (ITC) over alleged patent infringements by Hynix last September, seeking a ban on imports and sales of NAND chips made by the Korean firm. In a tit-for-tat move, Hynix lodged a similar complaint with the ITC in late October, claiming the Japanese company violated Hynix’s NAND-related patents and seeking a ban on imports and sales of Toshiba products. The ITC announced in early November a decision to investigate the allegations made by Toshiba against Hynix.

Unlike DRAM chips, NAND chips can retain data even when electric power is turned off. The NAND chip market is also being driven by booming demand for tiny portable music players such as Apple Computer’s iPod nano.

Market-research firm iSuppli said last year it expected the global NAND market to grow 42% in revenue terms in 2005 to reach $9.42 billion, compared with single-digit growth for the overall chip industry. Toshiba also expects global NAND chip sales to double in 2008 from the 2005 level. Thanks to robust demand and tight supply, prices of NAND chips have been stronger in recent months than previously expected.

Toshiba is the world’s second-largest maker of NAND chips, after Samsung. Hynix and other DRAM chip makers also have entered or are entering the fast-growing and lucrative market for NAND chips. Driven by robust sales of NAND chips and the products they power, Samsung is said to be closing the gap on Intel, the overall semiconductor-industry leader.

Separately, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. said on Jan.31 that it had filed a countersuit against Samsung Electronics in a U.S. court, claiming the South Korean company infringed patents related to technology for controlling DRAM chips. Matsushita said the suit was filed a day earlier in reaction to a suit brought by Samsung Electronics against it in a federal court in Texas late last year. Matsushita pulled out of the DRAM market in 1998.

Japan’s countervailing tariffs on Hynix’s DRAM chips are expected to have little, if any, negative impact on the Korean maker as it has taken steps to weather punitive tariffs in its major export markets, such as the US and the EU as well as Japan. When the WTO’s final ruling on the dispute with the US was announced, a Hynix official said the continued imposition of extra duties would not be a problem for the company once plants in Taiwan and China would go into operation late last year and early this year.

In response to the news of the Japanese decision against its products, Hynix said it expects “little substantial damage” to its business, adding that it will increase exports of chips not covered by the tariffs, such as NAND flash memory chips. It also plans to use overseas manufacturing bases. Hynix makes DRAM chips in the US, has a manufacturing relationship with a company in Taiwan and also plans production at a new plant in China this year.

The Japanese trade sanctions against Hynix come at an awkward time for relations between Tokyo and Seoul. Bilateral relations have plunged to their lowest point in decades because of Koizumi’s repeated visits to Yasukuni Shrine, the territorial dispute over islets called Takeshima in Japan and Tokdo in South Korea, and the fracas over Japanese textbooks authored by right-wing scholars for use at high schools.

Japan and South Korea launched negotiations on concluding a free-trade agreement (FTA) at the end of 2003. But the negotiations have been stalled in the past year amid strained relations. They failed to meet the original goal of striking an FTA by the end of last year. South Korea demanded that Japan agree to eliminate its import quotas on 17 categories of marine products, including laver (an edible seaweed), mackerel, horse mackerel and squid. Japan is the only industrialized country to impose import quotas on marine products.

Separately, Seoul lodged a complaint with the WTO against Tokyo in December 2004 demanding abolition of a Japanese import quota on laver. The two countries reached a settlement on the laver trade spat in mid-January, with Tokyo pledging to quintuple its import quota on Korean laver by 2015 and Seoul agreeing to withdraw its WTO complaint in return.

Further industry consolidation ahead?

Japanese makers were once in the driver’s seat in the overall semiconductor market in terms of sales and became the target for fiery protectionism in the United States. Excessive dependence on Japanese computer chips even raised national-security concerns in the US; but their position has significantly weakened in recent years.

According to research firm Dataquest, three Japanese makers – NEC, Toshiba and Hitachi – topped the list of semiconductor makers by sales in 1988, when Japanese makers were in their heyday. But Japanese makers began to be displaced by US, European and Korean rivals soon afterward. In 2004, Intel, Samsung and Texas Instruments were ranked the world’s No 1, No 2 and No 3, respectively. Among the top 10 semiconductor makers that year were three Japanese companies: Renesas Technology, a joint venture between Hitachi and Mitsubishi Electric; Toshiba; and NEC Electronics, which was spun off from NEC in 2003.

Last year Japanese chip makers further declined in the ranking. According to a preliminary report released in December by US market-research firm iSuppli, Intel, Samsung and Texas Instruments retained their No 1, 2, and 3 positions by semiconductor sales in 2005. The three companies all outpaced the growth in sales in the world semiconductor market, which increased 4.4% from 2004 to $237.3 billion. Among other Japanese companies, Renesas Technology slipped from the No 5 to the No 7 position, and NEC Electronics fell from No 8 to No 10.

Although Toshiba moved up to the No 4 position from the previous year’s No 7, backed by booming sales of NAND chips, the Japanese maker is also expected to face tougher competition this year and beyond. In late November, Intel and Micron Technology announced plans to form a company to make NAND chips, jointly pledging up to $5.2 billion to create a rival to the Asian companies that now dominate the market. The joint venture gets significant support from Apple Computer Inc. The computer maker, which needs huge numbers of NAND chips for its music players, will pay $250 million each to Intel and Micron for a share of the new venture’s output.

While fiercely competing in the global marketplace, Samsung and Sony also work together, as in a state-of-the art plant in South Korea that makes the liquid crystal displays (LCDs) used in hot-selling flat-panel televisions. The unlikely alliance shows just how tangled the connections have become among consumer-electronics companies as competition in the industry intensifies. The same trend can be seen among Japanese electronics makers themselves, which have traditionally prided themselves on doing as much themselves as possible, from the design of their gadgets to the technology used for them.

In January, Hitachi, Toshiba and Renesas Technology announced they will decide in six months whether to build Japan’s first factory to make customized chips to compete against foreign rivals. The three Tokyo-based companies said they will create a holding company to plan the venture. The factory would make system LSI (large-scale integration) chips with a circuitry width of 65 nanometers (billionths of a meter) or less, the smallest commercially produced. A former vice president at NEC Electronics will direct the venture. NEC Electronics is not involved. Most advanced semiconductor plants use 90-nanometer circuitry. Intel recently announced plans for a $3.5 billion, 45-nanometer semiconductor factory in Israel.

Hitachi has said it will ask NEC Electronics, Matsushita Electric Industrial and others to join the new company in a bid to build a joint chip-production plant. These companies are prepared to invest massively in computer-chip production equipment to revive the domestic semiconductor industry.

Independently, Toshiba, Sony and NEC Electronics announced on Feb.1 that they will jointly develop manufacturing technology for a next-generation system LSI chip. Toshiba and Sony have been engaged in joint development of manufacturing technology for system LSI chips with a circuitry width of 45 nanometers since early 2004. Toshiba and NEC Electronics said last November that they had started discussing a comprehensive alliance in their semiconductor operations. NEC Electronics had warned in late October that it would fall deep into the red this fiscal year after falling sales and prices for a range of its chip products. Matsushita Electric Industrial has formed a manufacturing technology-development alliance with Renesas Technology while Toshiba and Sony have forged a similar alliance.

Joint production is seen as one way that chip makers can pool resources and cut costs. The goal is to produce smaller, faster chips that consume less power. This would allow electronics makers to make smaller products. The Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) has apparently played a leading role behind the scenes in promoting industry consolidation. Despite the recent moves toward consolidating the semiconductor industry, however, many industry experts agree that further realignments are inevitable if Japanese makers are to weather increasing competition from US and Korean rivals. Whatever happens, there is little prospect that Japan’s chip makers will experience a return to the “good old days”.

‘Aggressive legalism’

The latest Japanese decision against Hynix products has raised questions in some quarters: Does it represent a significant shift in trade policy portending a rise in protectionism in the world’s second-largest economy?

Japan has pursued “aggressive legalism” in the past decade, after its grueling auto trade war with the United States in the mid-1990s. The tenacious US demand that Tokyo to set numerical targets for imports of US auto parts – and Japan’s rejection – brought the two countries to the brink of an unprecedented trade war. The US slapped a prohibitively high tariff of 100% on imported Japanese luxury vehicles under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, and Japan filed a complaint with the WTO against the US measure. It was the first time Japan had taken a trade dispute with the US to the WTO. Unilateral trade measures like the ones under the Section 301 were declared illegal by the WTO later.

In the mid-1990s, Japan began clearly to say no to what it deemed unjust US demands that contravened international trade rules, and also began to refer the US to the WTO over WTO-incompatible laws and trade measures. This marked a significant departure from postwar Japanese trade policy. Previously, Japan had typically conceded in the face of the threat of US sanctions.

Japan has since filed complaints with the WTO against the US over such trade measures and laws as the anti-dumping duties on hot-rolled steel imports, the failure of the US to repeal the Antidumping Act of 1916, and the so-called Byrd Amendment, and has won in all cases. Last September, Japan joined the EU and Canada in taking the WTO-sanctioned step of imposing extra import tariffs on US steel and other products in retaliation for the US failure to rescind the Byrd Amendment, which was declared in violation of international rules by the WTO. It was the first time that Japan had taken such a WTO-sanctioned retaliatory trade measure against any trading partner. (The Byrd Amendment directed the US government to distribute collected anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties to the US companies that had brought the cases.)

Another pending case at the WTO involves Japan suit over the controversial US “zeroing” practice of calculating anti-dumping duties. In the current Doha Round of global trade talks under the auspices of the WTO, Japan is a key member of a group dubbed “AD [anti-dumping] friends” calling for stricter rules against abuse of anti-dumping duties by WTO members, especially the US. Japan’s aggressive legalism on trade was facilitated by the fact that the WTO succeeded the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in January 1995 as a more powerful global watchdog on commerce with stronger dispute-settlement functions

In stark contrast with Japan’s much touted “aggressive legalism” on the export front, however, Japan has been highly cautious about resorting to import measures under the so-called trade-remedy laws, such as “safeguard” import restrictions, anti-dumping duties and countervailing tariffs. That is because it fears being criticized by targeted trading partners as protectionist, or at least as ungenerous, in light of its colossal trade surplus with the rest of the world. Japan also has a trade surplus of about $20 billion annually with South Korea.

Still, the relative decline of Japan’s economic power since the “bubble economy” bust of the late 1980s not only generated protectionist pressure from weak domestic industries, but also has relieved the country of some of the moral shackles that had made aggressive legalism difficult to pursue.

“Safeguard” import restrictions have been imposed only once. Japan imposed such restrictions for the first time in early 2001, albeit on a temporary basis, on three Chinese agricultural products – stone leeks, shiitake mushrooms and igusa rushes, the straw used for tatami mats. This invited an angry retaliation from China, which slapped punitive 100% import duties on three Japanese industrial products – automobiles, air conditioners and mobile phones. Japan lifted the import restrictions after the two countries agreed on an “orderly trade” in the three farm products in question.

Japan imposed anti-dumping duties only three times, on ferrosilicon manganese from China in 1993, cotton yarns from Pakistan in 1995 and discontinuous polyester fibers from China and Taiwan in 2002. Countervailing tariffs had never been levied before the Hynix case. Domestic cotton-yarn makers applied for government protection from Pakistani imports in 1982 through countervailing tariffs, but withdrew the application. Domestic ferrosilicon producers filed an application for countervailing tariffs against Brazilian imports in 1984, but also withdrew the request. Japan is expected to face more trade rows with South Korea – and with China –not only in agriculture but also in high-tech sectors.

Hisane Masaki is a Tokyo-based journalist, commentator and scholar on international politics and economics. Masaki’s e-mail address is [email protected].

This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in Asia Times, January 27, 2006. Posted at Japan Focus on February 3, 2006.