Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On

Han Kyung-Koo

This is the second of two paired articles which view the U.S.-Korean War through the lens not of great power conflict, or even of contending armies in a civil war, but from the perspective of its impact on Korean society in countryside and city, and the continuing traumas that remain unresolved sixty years late. The first article is

Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas

The Korean War, which began with North Korea’s surprise invasion of South Korea on Sunday, June 25, 1950, lasted for three years. The hostilities ended with the signing of an armistice agreement in July 1953. This war broke out only five years after the Korean Peninsula had been liberated from Japanese colonial rule, and only three years after the establishment of separate North and South governments, in a nation divided by foreign powers. The war’s devastation left much of South Korea in ruins, along with its people in social turmoil. Sixty years hence, South Korea now strives to play a central role in resolving the common problems of the global community, as evidenced by its hosting of the G-20 Summit in Seoul, in November 2010.

|

Korean War Monument in Seoul |

South Koreans developed a boundless vitality and resiliency, but also suffered from serious trauma. Various aspects of the Korean people and their culture, which have been perceived in a negative light, are rooted in the scars of this lengthy period of crises and their experiences with the atrocities of war.

The Korean War was a significant incident in terms of international politics, but it resulted in an even more profound impact on the socio-cultural characteristics of Korean society. Liberation from Japan’s colonial rule in 1945 was historically significant, and the establishment of the government of the Republic of Korea was a notable development as well, but the Korean War, which began in 1950 and saw an end of outright hostilities under an armistice agreement in 1953, was of such pervasive influence that it has shaped the behavioral patterns, way of thinking, and value systems of South Koreans, as well as the direction of South Korean society’s development, from the time of the war’s outbreak and long thereafter.

Overview of the Korean War

The Korean War got underway at 4:00 in the morning on Sunday, June 25, 1950, with a full-scale surprise invasion of the South by North Korean forces. At an overwhelming disadvantage in terms of equipment and training, South Korean troops were forced to repeatedly retreat southward. Even after the U.N.-sponsored troops arrived in the South, at one point, North Korea had come to occupy almost the entire Korean Peninsula, except for areas of the Gyeongsang-do provinces, making it seem that unification of the peninsula by force was only a matter of time. But the U.N. troops countered with a successful landing at Incheon, from where they were able to liberate Seoul and then continued northward to take Pyongyang, and eventually reach the Amnokgang (Yalu) River. Thereafter, upon China’s entry into the war, Seoul was again lost, followed by a counterattack that featured especially fierce fighting along the current armistice line, until a ceasefire was declared in July 1953.

Practically the entire Korean Peninsula experienced the ravages of war. With the front line being continuously pushed back and forth, tremendous toll in human life and widespread physical destruction left Korean society in serious turmoil. This resulted in large-scale movements across social and class lines, and the development of new social and physical infrastructure as the divided peninsula struggled to recover from the war. Following a virtual collapse of longstanding personal relationships and value systems, a process of modernization gained momentum and new value systems emerged. As such, the pace of urbanization and industrialization accelerated as well. Since everyone had suffered from this terrible loss of life and wartime devastation, followed by extreme poverty and hunger, as well as the separation of families and a clash of ideological views, they were compelled to join hands to promote economic development in order to overcome poverty and the threats of war and communism, which led to a thirst for peace, security, education, and culture.

Moreover, the arrival of U.N. troops resulted in a tremendous culture shock for South Koreans. As a result of their large-scale, active involvement, the United States, in particular, became an overwhelmingly important “other country” among South Korean society, during and after the war. American military and humanitarian aid, along with their advanced technology, material abundance, values of democracy, and the appeal of U.S. culture, all served to influence the way that Koreans perceived the United States.

Refugee Experience

In the early stages of the Korean War, the South’s porous defensive efforts and misguided measures of an inexperienced government resulted in North Korea’s occupation of numerous South Koreans, who were forced to comply with orders of the Northern troops. The chaotic situation was worsened by the South Korean government’s bold pronouncements early on, only to find itself hastily abandoning Seoul shortly thereafter. Many of the people who did not escape the sudden onslaught suffered from such atrocities as massacre, torture, imprisonment, and abduction, while those who survived were often branded “collaborators,” leaving them with a permanent black mark. The so-called background checks, which were rigorously enforced through the 1980s, served as a de facto guilt-by-association system that did not allow suspected individuals to assume public office.

|

Refugees Fleeing across the Han River, 1950 |

The South’s defense of Seoul was twice overrun by the North. With the intervention of China’s People’s Volunteer Army, South Korean and U.N. forces were again forced to retreat from Seoul, as part of a massive exodus of people fleeing southward, by land and sea. Consequently, the city of Busan, with a population of about 400,000, suddenly found itself home to more than one million people. The more fortunate families were able to cram themselves into small rooms; those less so made do with cardboard boxes, wood planks, and makeshift tarp coverings for shelter.

Of note, the fact that areas in the Gyeongsang-do provinces, including Busan and Daegu, had managed to avoid the North’s occupation, served to influence the development of South Korea’s modern society. In particular, the residents in these areas escaped the worst of the war’s physical destruction, along with generally being free from accusations of being “collaborators,” thereby avoiding social obstacles after the war’s end. Since it was thought that these areas were relatively secure, and would likely remain so even in the event of another conflict, leading institutions and figures from across the country formed a close bond with these areas during the relocation period. As such, this circumstance enabled the southeast regions of Korea to develop more rapidly than the southwest regions immediately following the war.

Healing the Scars of War

Although the senseless loss of countless people and vast destruction that left much of the country in rubble, the war’s consequences were far more profound. The hearts of all South Koreans were deeply scarred. The war and its aftermath exerted a significant influence on the behavioral patterns and ways of thinking of South Koreans for quite some time. In Japan, the “Fifteen Year War” includes the period that began with the Manchurian Incident in 1931, followed by the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, and ending with Japan’s defeat in the Pacific War in 1945. Having suffered under Japanese colonial rule during this period, the tension and sense of crisis reached a peak in Korea as well. Furthermore, it was only a few years after Korea had finally freed itself from Japan’s militarism and wartime mobilization that it experienced national division and the horrors of such a cruel war. Even after the armistice, the state of confrontation between the South and the North has continued. In this way, South Koreans have endured decades of tension and struggle to survive.

Through this extreme hardship, South Koreans developed a boundless vitality and resiliency, but also suffered from serious trauma. Various aspects of the Korean people and their culture, which have been perceived in a negative light, are rooted in the scars of this lengthy period of crises and their experiences with the atrocities of war. When foreign troops and emissaries came to South Korea, they encountered a people in the midst of a horrific war, before wounds from the “Fifteen Year War” period had even healed. That Korea’s emergence on the world stage came about due mainly to the Korean War has had a truly unique influence on the formation of perceptions toward Korea and the Korean people.

For many in South Korea, the war led to their first real encounter of life outside their local community, whether through their military service or as refugees, who struggled for survival with complete strangers from across the country. Amidst this crisis situation and desperate struggle for survival, those who practiced forthrightness were thought to be ineffectual, while a notion took root that anyone who “followed the rules” would not survive. Under these circumstances, people came to believe that competing fairly and clinging to traditional values would only lead to failure. Poverty and an abject lack of material possessions encouraged such untoward behavior as cutting in line and resorting to expediency. There was also a tendency to justify breaking the rules by claiming that the competition was unfair or that others would ignore the rules as well.

Even as the ravaged cities were rebuilt and the people extricated themselves from the depths of poverty through Korea’s economic recovery, the trauma that people experienced due to the horrors of war would take much longer to heal. Even though the crisis situation had ended, after having endured such a tumultuous everyday life, it was no simple matter for the thoughts and behavior of people to return to a state of normalcy. Moreover, even the succeeding generation, who did not directly experience the war, could not be free from the influence and memories of their deeply traumatized parents.

Although a number of key issues still need to be resolved, as Koreans commemorate the 60th year of the start of the Korean War, the wartime trauma has loosened its grip with the passage of time. Even as the state of South-North division and confrontation continues, South Koreans have managed to attain democratization and the peaceful transition of government power. Freedom of the press has been expanded, along with a notable improvement in the respect for human rights. For most, there is still cause for concern, but the desperate sense of crisis that had existed for so long is fading away.

Vestiges of Nationalist Education

The wartime chaos and its aftermath greatly impacted the educational system in Korea. As in Japan, which had pursued imperialist aggression that resulted in its defeat, the democratization of its education was promoted by the U.S. occupation authorities. But in Korea, which had been victimized by Japan’s militarism and colonial rule, the vestiges of Japanese-style nationalist education remained in place for a considerable period of time due to such factors as national division, anticommunist measures, and national security concerns.

Prior to the Korean War, the Ministry of Education had required all students to memorize a credo known as “our oath,” which included the following pledges. First, “We are sons and daughters of the Republic of Korea, and we will defend our nation to the death.” Second, “Let us defeat the Communist aggressors, for we are bound together like steel.” Third, “Let us wave the Korean flag on the summit of Mt. Baekdusan and achieve the unification of South and North.” This oath was printed in all books, not only textbooks. When the war broke out, the participation and sacrifice of student soldiers were glorified, while Student National Defense Corps were formed on school campuses, and students participated in military training. It was not until the 1980s that regulations on student hair length and clothing were relaxed as part of a gradual elimination of the authoritarian-era aspects of education.

Dietary Practices

The Korean War brought about dramatic change to the dietary practices of South Koreans. Food items such as coffee, gum, chocolate, candy, biscuits, and powdered milk were introduced to the general public by the U.S. military. Under a U.S. agricultural program, an abundance of surplus wheat flour was supplied to Korea, which led to the development of flour-based foods, including the Korean-style dish of noodles with black bean sauce.

In addition, North Korean dishes, such as cold noodles, gained a foothold in the South. Of course, a variety of North Korean foods, such as Pyongyang cold noodles, was already popular in Seoul and other large cities, but the massive inflow of North Korean refugees during the war helped to spread the Northern cuisine to every corner of the country. The Northerners who had fled to the South opened numerous restaurants in their new land. As a result, Northern-style dishes such as cold noodles, meat with noodles soup, beef soup with rice, mung bean pancakes, and fermented flatfish became favorites in the South. Until recently, you could easily notice former North Koreans at Northern-style restaurants in Seoul and other large cities, including those in Ojang-dong and Euljiro that specialized in cold noodles, and the ham hock establishments in Jangchung-dong.

Pyongyang cold noodles, which had long been a special treat in the South, found its way onto the regular menus of Korean restaurants across the country soon after the Korean War. Meanwhile, the dish known as mixed noodles or mixed hoe (raw fish) noodles in Hamgyeong-do Province, was renamed Hamheung cold noodles after the war. People say that the new name was an attempt to have this dish associated with Pyongyang cold noodles, which had already gained widespread popularity.

Religious Beliefs

The division of Korea and the Korean War played a central role in shaping the attitudes of Koreans toward religion. In the case of shamanism, South Korea maintained a tradition of hereditary shamans, under which the shaman title was passed down from one generation to another, while North Korea recognized spirit-possessed shamans, whereby it was necessary for a shaman to demonstrate spiritual powers. However, upon the establishment of the Democratic People’s Republic, the Northern regime harshly persecuted North Korean shamans, who were forced to seek refuge in the South during the war. Consequently, as spirit-possessed shamans from the North integrated themselves into the South, the traditional shamanist community emerged with a new face.

Mainstream religions and individual sects were affected by the war in varying ways. For example, because a large majority of Chondogyo (Religion of the Heavenly Way) followers were from the North, the number of its adherents plummeted. Confucianism and Buddhism also experienced considerable contraction, while Protestantism and Catholicism expanded quite noticeably. With more than two-thirds of Presbyterian Christians living in North Korea, when they became a target of persecution by the Northern regime, there was a large-scale exodus of believers and leaders to the South, where they visibly influenced the postwar development of Christianity in Korea. Of particular note, churches such as Youngnak Presbyterian Church and Choonghyun Church in Seoul, founded by “Northwestern Christians” from Pyongyang, played a prominent role in the anticommunist efforts of Korean society.

Belief in Christianity spread widely during the war through missionary outreach efforts among the military personnel and POW detainees as well. It has been noted that the Christian leaning administratin of President Syngman Rhee’s also served to promote its acceptance among the general populace. Christianity was seen as a means to obtain relief supplies, as well as a pathway to the United States and a way to taste a piece of the American lifestyle in Korea. With so many Koreans relying on the church for food aid, the United States came to be stamped indelibly into the minds of Koreans as a “land of grace.” There are scholars who trace a tendency among Christian circles, to believe that material blessings will naturally follow from a belief in Christ to people’s experiences of the war and its aftermath.

|

Myongdong Catholic Cathedral in Seoul |

Some believe that Christianity gained considerable popularity because, unlike other religions, it offered a sense of community and an explanation of sorts to help people understand the irrationality of war atrocities. The war resulted in the massive displacement of people, in terms of geography and social status, while the Christian church offered these newcomers emotional stability and social cohesion. In particular, the churches founded by refugees from North Korea provided a sense of community for those who had been so abruptly uprooted. In addition, some Christian leaders thought of the Korean War as “a trial imposed by God so that He might use the Korean people as a means to achieve world salvation,” while others interpreted it as a sign of a coming of the world’s final judgment. Although limited to a small group of people, this interpretation had the effect of making understandable an utterly cruel, incomprehensible reality.

Inflow of Refugees

Along with the Korean War’s massive scale and substantial loss of human life, another far-reaching consequence was its displacement of countless people who were forced to abandon their homes. In most cases, it was not possible for people to relocate in family units; many men left themselves to ensure that the family name would survive, or perhaps because other family members were incapable of making the journey, resulting in vast numbers of separated families. It has been estimated that some 1.5 million people fled southward during the eight-year period from 1945 (when Korea was liberated from Japanese colonial rule) to 1953, which marked the end of the Korean War. Moreover, the relocatees are said to have left behind some 4.5 to 6 million family members, equal to a 15-20 percent share of the 1950 population.

People from North Korea most often settled in the cities, which contributed to the South’s urbanization and modernization efforts in the 1950s, although this did result in the emergence of low-income slum areas. At that time, South Korea’s urban residents accounted for about 24.5 percent of the overall population. Former North Koreans resettled in large numbers in border regions, such as Sokcho, which drastically altered the local community makeup.

Before liberation, the residents of northwestern Korea were known for being open-minded and progressive, along with being well educated and successful in business, and many of them were Christians. Since those who fled from the North did so for their survival or to pursue a better life, it was natural for these refugees to bring a strong sense of survival and resiliency to South Korean society.

Many refugees emphasized their anticommunist beliefs and even actively participated in the conservative anticommunism movement in South Korea. But they also suffered from extreme emotional distress over the family members they left behind, and many were watched carefully by the authorities. It was only in 1985, 32 years after the war’s end, that the first meeting was held to bring together separated family members from South Korea and North Korea. This was followed by a second reunion in 2000. There were also those who made their way to the United States for a more secure environment and to pursue the American dream.

Benefits of Education, Military Service

For Koreans, who had acquired a keen appreciation for the importance of education through the painful experience of colonial rule, the war taught them that modern education could well mean the difference in your very survival. Mandatory military service was postponed for university students during the war and the post-war reconstruction period as well, while English-language competence and modern education were essential to open the doors to employment opportunity and social advancement. Indeed, material wealth could be destroyed or looted during war, but education was a “secure” asset, as well as a pathway to social status and economic prosperity. Education has thus determined the fate of entire families. It could be said that the passion for education among modern-day Koreans may well be attributed to the lessons learned from the Korean War.

|

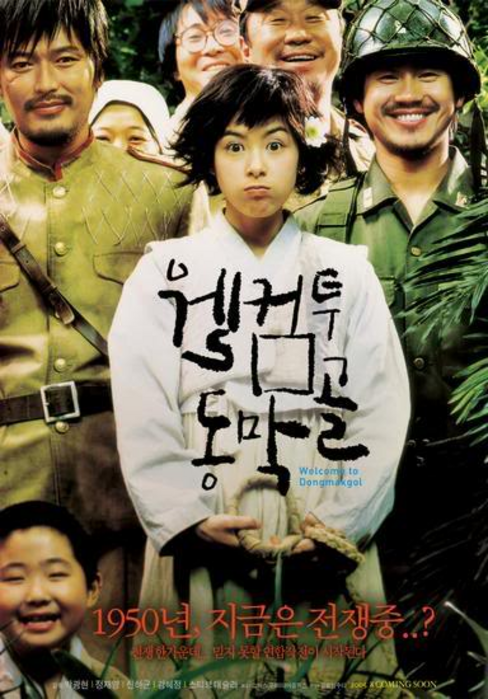

The Korean War in Cinema, Dongmakgol (2005) |

Even after the signing of the armistice agreement brought an end to the battlefield hostilities, peace was not established and the state of South-North confrontation continued. For its security, South Korea was forced to maintain a 600,000-member military, a massive commitment when compared to the nation’s population, and as a result, all Korean men were required to serve in the military. Due to the war, the ongoing confrontation between South and North, and U.S. military aid, military service provided valuable opportunities for education and training, while the government’s generous support of the military enabled it to secure advanced know-how and organization practices. Although anticommunist ideology played a notable role, this military-centered environment set the stage for Korea’s military coup d’etat and authoritarian regimes.

For Korean men, military service provided an entrance into society, as the lessons learned about the military’s teamwork, cooperation and organizational principles proved to be of significant value in the civilian sector as well. Critics claim that military service contributes to an excess of macho tendencies in Korean society and a reinforcement of the patriarchal and authoritarian systems, along with creating obstacles to true democratization. But the pre-war generation in Japan was known to admire Korean men for their strength of character and fighting spirit, as well as a strong sense of camaraderie, as a result of their military service. Moreover, they seem to lament an absence of these characteristics in Japan’s post-war generation.

Han Kyung-Koo is a cultural anthropologist and professor in the College of Liberal Studies, Seoul National University. He wrote this article for the special issue of Koreana, vol 24, No 2, Summer 2010 on “60 Years after the Korean War.”

It is reproduced here with the permission of both the author and the editors of Koreana, which The Asia-Pacific Journal acknowledges with thanks.

Recommended citation: Han Kyung-Koo, “Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 38-3-10, September 20, 2010.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War. • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Heonik Kwon, Korean War Traumas.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Kim Dong-choon, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War • Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War. • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Wada Haruki, From • Nan Kim |