Debt, Networks and Reciprocity: Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan1

Gracia Liu-Farrer

Abstract

Fujian, the coastal province in Southeast China, is where a large number of overseas Chinese called home. After widely publicized tragic events such as the Golden Venture and Dover incidents, the name Fujian has in recent decades become associated with clandestine border entry. This article examines the causes and contexts of undocumented migration from Fujian to Japan. It highlights the unique characteristics of undocumented migration into Japan: debt-driven migration and network- induced visa overstaying. It also explores the tradition- and reciprocity-oriented ethical frameworks within which Fujian undocumented migrants justify their behavior.

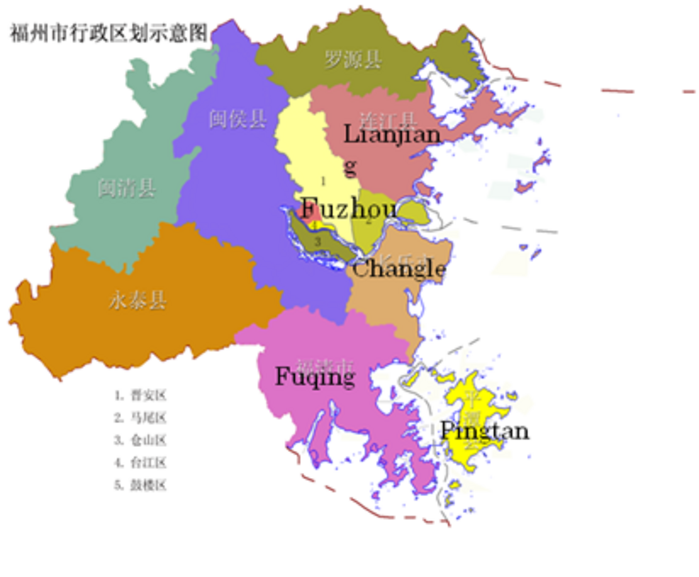

Fuzhou City and its surrounding cities and counties are reputed to have sent out large numbers of international migrants. The map is a modified version of its original map in Chinese. For more detailed information on the location of Fujian, please refer to Google Map.

Taiwan fears Pingtan,

Americafears Tingjiang,

Japan fears Fuqing,

Britainfears Changle,

and the whole world fears Fujian.2

Contemporary Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan

Fujian, the coastal province in Southeast China, is where a large number of overseas Chinese call home. After widely publicized tragic events such as Golden Venture and Dover incidents, in which dozens of Chinese immigrants died, the name Fujian has in recent decades been associated with clandestine border entry. As the popular saying above indicates, Japan is also considered a prominent destination for Fujian undocumented migrants, especially from the area around the town of Fuqing.

In 2009, over six hundred thousand Chinese nationals lived in Japan, making up nearly 30 percent of all foreign residents in this country. While being the largest legal foreign population, the Chinese are also possibly the largest undocumented migrant group. The official data lists the Chinese visa overstayers in 2009 to be 18,365, behind the 24,198 Koreans.3 However, the number does not tell us how many Chinese entered Japan clandestinely through human trafficking. Ministry of Justice (2009) data show that among people who were refused border entry in 2008, a third of them were from China.

Fujian migrants are likely to be the single largest group of undocumented Chinese migrants in Japan. First, among visa overstayers, a large number of Chinese immigrants who became undocumented were from areas around the capital city of Fujian Province, Fuzhou. There is no official statistics that show the regional breakdowns of Chinese visa overstayers. However, two observations point to Fujian as the major sending region for overstayers. One observation is that 40.2 percent of the Chinese who became undocumented in Japan came as students, including both university-bound (ryuugakusei) and pre-university language students (shuugakusei) (Ministry of Justice 2004). In fact, over 80 percent of total student visa overstayers were from China. And statistics from the survey show that the rate of Fujian students who became undocumented was much higher than students from other regions in China (Liu-Farrer 2008). The other observation is qualitative. In my fieldwork at both Chinese immigrant social dance halls and immigrant religious congregations I encountered many women from Fujian who were in Japan on a spouse visa, but the marriage was in fact just a piece of paper. Many of these women had already overstayed their visas when I met them.

In addition to visa overstayers, the Fuzhou area also produced a large number of clandestine immigrants. It was estimated that as many as 50,000 Chinese were smuggled into the US every year (Chin 1999). Although it was not likely to count the number of clandestine entrants into Japan, since 1990, 80 percent of illegal entrants into Japan apprehended by Japan’s Coast Guard were Chinese, and almost all were from Fujian.4 Since the mid-1990s, the number of apprehended clandestine entrants from China has exceeded one thousand every year. A fifth of Fujian immigrants sampled in my survey entered without legal status, while no other region reported clandestine entrants (Liu-Farrer 2008).

However, Japan is no easy country for undocumented migrants. Although the Japanese government has been more welcoming toward skilled workers in recent years, its response to undocumented immigrants has always been one of strict prevention. Japan does not have a precedent of amnesty. Moreover, due to the common association of illegal stay with criminal activities, especially after human smuggling became rampant since the early 1990s, its police have been particularly adamant in clearing the streets of undocumented immigrants. In December 2003, in order to make Japan into “a strong society against crimes,” the Japanese government, targeting “illegal immigrants as the hotbed of foreigner’s criminal activities,” launched a campaign to reduce the number of illegal foreign residents by half in five years. Since then, under the slogan of “internationalize by abiding rules (ruru wo mamotte kokusaika),” a designated month has been set aside for and “anti-unlawful employment campaign”. The police regularly raid locations where illegal immigrants are likely to concentrate, such as entertainment districts, construction sites, and some residential areas. Plainclothes roam train stations and neighborhoods trying to identify suspects by appearance. Five years later, by the end of 2008, the number of unlawful stayers (fuhou zanryusha) was reduced by 48.5 percent from 220 thousands to 113 thousands.5 Among deported foreigners, Chinese consistently ranked number one.

Becoming undocumented therefore put immigrants into a precarious situation in Japan. The fear of deportation not only prevented illegal immigrants from seeking protection from Japanese labor regulations, it also forced them to organize their daily life to minimize the danger of encountering the police. Many undocumented immigrants do not ride a bicycle, and scarcely go to see a doctor. Some Fujian informants became tense when they walked in areas where they believed the plainclothes patrolled. There was a fatalistic sentiment among the undocumented immigrants. One interviewee ended our conversation saying, “Today I am here talking to you. Tomorrow I don’t know where I will be.” Moreover, undocumented immigrants heavily relied on their personal networks for resources and services and therefore were vulnerable to exploitations by co-ethnics. Within ethnic networks, services such as introduction to a job usually came with a price. Having a baby in Japan could easily cost an undocumented couple over a million yen after paying the hospital bills, the borrowed insurance card, and the fee for sending the baby back to China.6 In addition, undocumented immigrants were likely to be targets of criminal activities. The victims of crimes committed by Chinese were often other Chinese. Undocumented immigrants were too afraid to report threats and damages.

Given the harsh situations an undocumented immigrant faces, why have so many Fujian people come to Japan clandestinely or relinquished their legal status in Japan? This article explores the causes of undocumented migration from Fujian to Japan, presents the ethical frameworks within which Fujian undocumented migrants operate, and discusses different concepts of rights involved in the act of irregular migration.

This study is based primarily on 47 in-depth interviews with immigrants from Fujian Province between May 2004 and February 2005 in Kanto area, Japan and Fujian, China. I also use in this paper field notes from participant observation in various Chinese leisure and religious institutions in Tokyo Metropolitan area since early 2002. The statistical data in this paper came from a sample survey of 218 Chinese immigrants, which I designed and administered between May and December 2003, and statistical reports published by the Immigration Office of Japan Ministry of Justice and Japan Immigration Association on foreign residents and visa overstayers.

Causes of Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan

Researchers in US, Europe and China have documented the motives and methods of migrants leaving Fujian Province, especially the several towns and villages around the capital city Fuzhou (Chin 1999, Kwang 1997, Pieke et al. 2004, Liang 2001, Liang et al. 2008, Liu-Farrer 2008). Economic motivations, psychological reasons and network effects are all suggested as causes for undocumented migration out of this region. These mechanisms are saliently present in the undocumented migration from Fujian to Japan. However, in the phenomenon of undocumented migration in Japan, unique patterns of economic causes and network effects are observed: these are debt-driven illicit border entry and network-induced student visa overstaying. In this section, I elaborate on the causes for migration from Fujian to Japan, introducing both the mechanisms that are considered common to all clandestine migration out of this region and phenomena that are particular to migration into Japan.

Economic motivation: capital and debts

Economically, there is not sufficient arable land in Fujian for each productive person. Costal people used to fish, but in recent years diesel fuel became increasingly expensive making fishing unprofitable. In some areas, the coastal area was leased for commercial fish farming after economic reforms, and local people no longer have access to it. Entrepreneurship and out migration have been two traditional economic practices in this region. Lacking alternative sources for business loans, Fujian people obtained initial capital by pooling family resources, borrowing high interest loans, and joining rotating credit associations. International migration provided an alternative means for accumulating capital, and becomes a household strategy, typical of many rural migrant-sending regions (Massey et. al 1993, 1994). Many Fujian immigrants reported shouldering the responsibility for bringing money to invest in family businesses as well as the household’s general well being. Ajin had an elder brother who was running a factory. He provided the capital they needed, and had a share in their business investments. “It is called division of labor,” he said. Since these immigrants’ remittances were frequently lost in unsuccessful business investments or entrepreneurial efforts (due largely to lack of business experience), they were forced to remain in Japan to accumulate more cash. There were also informants who came to Japan for the second or even third time because the money they previously made in Japan was lost in failed business attempts.

However, one additional reason for undocumented Fujian migrants coming to Japan was debts. Debt drove clandestine migration in many instances. Interviewees specifically pointed out that Japan was not an ideal destination for international migration because it was not an immigrant country and provided neither amnesty nor opportunities to legalize status. The US, Canada, and Australia were more attractive places for long term settlement. However, they came to Japan because of debts from failed entrepreneurial activities. Japan was nearby and was believed to have many temporary jobs. Older male migrants were especially likely to come to Japan because of debt.

Nian’s case is typical. A 46-year-old immigrant from Changle County, Nian landed in Japan with debts amounting to more than 500,000 RMB (7 million yen). He operated a pearl farm in the early and mid 1990s. In 1995, the area experienced the biggest hurricane in over a century. In just seconds, he lost everything. “A wave swept everything away. I owed people 200,000 RMB (2.8 million yen).” Without insurance against disaster, he could not possibly stay home and repay the debt. He fled. Borrowing an additional 200,000, he came to Japan by boat in 1996.The journey was not an easy one. In Zhejiang province, their boat was detained. And each of them paid the police a penalty of 30,000 RMB (400,000 yen). He waited for several months, not wanting to go home, fearful of attempts to collect his debts. Months later he was put on a boat again but had to abort the plan several times in two months. When the voyage eventually happened, it took ten days at sea to reach Japan.

Psychological reasons: relative deprivation and personal worth

Economic reasons aside, Liang and Ye (1999) point out that relative deprivation was a factor prompting international migration out of the Fuzhou area. In Fuqing City and Changle County, tall new buildings built by migrant families stand like monuments displaying the wealth of households. Asked about their plans, many immigrants mention building a new house. One interviewee told me that he had worked seven days a week and 16 hours a day for the past three years in a lunchbox (bento) company before the boss had to let him go because the police was coming to inspect his employees’ documents. Not only did he pay off the fees for the clandestine boat trip within a year, he had already built a new house in his home village. Given a little more time, he would have had enough money to furnish the place. Immigrants from the Fuzhou area, whatever their status in foreign countries, were called overseas Chinese (huaqiao) by their fellow villagers. They were expected to demonstrate their success by throwing banquets upon returning, giving expensive gifts to relatives and friends, and contributing at least twice as much as non-overseas Chinese to the construction and renovation of ancestral shrines and other local public projects. These practices of conspicuous consumption not only placed an extra burden on migrants, but also produced more aspiring international migrants.

Some young people also consider going abroad to work as a way to prove their personal worth. 30-year-old Li had just returned to China to marry his girlfriend of ten years. Five years ago, over her family’s objection, Li came to Japan in order to make money to establish his own family. In China, he had not gone to high school, but went into business. By 25, however, his losses amounted to several tens of thousands RMB. All the money was borrowed from his mother.

In fact, my family did not need my money. I have a brother in the US making money. He has naturalized. But I wanted to have my own career, and make my own money. I had tried opening retail stores, and I also worked as a sub-contractor (gong tou). But I did not make any money. I felt like a loser. I was in a relationship with somebody, and I wanted to give my partner a comfortable life. …… My brothers gave me advice on how to do business, this and that. I was born in the year of tiger. I did not like to be commanded by others. I wanted to be independent. So I decided to come out [to Japan].

Kinship networks: resources and constraints

Besides economic and psychological reasons, network closure is an important mechanism that not only produces but also perpetuates undocumented migration out of Fujian (Liu-Farrer 2008). According to network theory, each act of migration creates the social structure necessary to sustain additional movement. Migrants are linked to non-migrants through social ties that carry reciprocal obligations for assistance based on shared understandings of kinship, friendship, and common community origin(Massey et al. 1993). Fujian Province, with its long coast line and geographic location, has a long history of emigration to Southeast Asian countries, North America, South America and Japan. Since the 15th Century, Fujian merchants had been active in the Kyushu area. Even during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries when both Japan and China closed their borders, smuggling continued between Fujian and Japan’s coastal areas. Until the 1980s, thousands of Fujian Chinese lived in Nagasaki and Yokohama’s Chinatown. Most were labors and craftsmen such as tailors and barbers. A minority were merchants (Vasishth 1997). In 1969, Fujian immigrants numbered 6193, and were the largest mainland Chinese immigrant group in Japan (Tajima 2003).

Aside from Fujian Chinese, there were also many Taiwanese in Japan who had Fujian origins and connections. Taiwanese, then Japan’s colonial subjects for half a century, migrated to settle in Japan before the end of World War II. Until the 1980s Taiwanese accounted for over half of all Chinese immigrants in Japan. The old Fujian and Taiwan overseas connections were important in channeling Fujian immigrants into Japan. According to several informants, overseas Taiwanese set up language schools in Japan and went to their hometowns to recruit students. Fujian students often found themselves in classes where the majority of students were from Fujian.

The old overseas Chinese community in Japan formed the base for transnational migration networks. What sustained and accelerated clandestine migration from Fujian to Japan, however, was Fujian immigrants’ kinship based migration networks characterized by a high degree of closure. Fujian immigrants were mostly from areas around the capital city Fuzhou (Liang and Ye 2001, Liang and Morooka 2004). With slight variations in accent, people from this region shared a common dialect that was almost incomprehensible to other Chinese. With these characteristics, Fujian immigrant networks appeared to be closed to outsiders.

Through these closed kinship networks, human smuggling became rampant in this region. International human smuggling out of Fujian is operated through an elaborate system involving underground societies and corrupt officials from different countries. Still, not only do the people in the smuggling ring often belong to a family or extended family or are good friends, but local recruitment is invariably done through kinship and friendship networks (Liang and Ye 2001; Chin 1999). I once asked an informant whether Fujian people were afraid of “snakeheads” — a term that equals criminals in mass media and for non-Fujian people. He was surprised. “Why? They are often relatives and people living in the same villages. Otherwise, why had so many young women been willing to come abroad? Those women probably had never even left the village.” Later I realized that “snakehead” was just a name for people whose business was sending immigrants abroad, legally or illegally. Some people called them “brokers (zhongjie).” In my fieldwork, I often heard remarks such as “my uncle was a snakehead,” “a relative of mine was a friend of a snakehead,” or “I used to hang out with snakeheads.” One woman interviewee said, “Being a snakehead was a hard job. They are in the same boat as you are. They are risking their lives together with you.” Most Fujian students also obtained their visas to Japan through a snakehead.

In fact, Fujian immigrants’ kin and friendship networks not only facilitate transnational migration, but were also important resources in immigrants’ adaptation process in Japan. The resources available through self-enclosed social networks, such as housing and job information, eased Fujian immigrants’ transition into a life in a new environment, and provided practical services that immigrants, particularly undocumented immigrants, depended on. However, as I have pointed out elsewhere (Liu-Farrer 2008), while useful for undocumented migrants to obtain resources, Fujian immigrants’ network closure also caused a high percentage of student visa overstaying among Fujian students. The networks became constraints that hindered obtaining alternative resources and blocked upward mobility. First, embedded in social networks within which the majority of people were undocumented, losing legal status was considered normal and even expected. Upon being asked how he made the decision not to go to the language school in Okinawa but came to Tokyo to work directly, a young man from Fuzhou said: “It is the influence of the environment. People from our region are all like this.”

Second, the resources that facilitated clandestine migration and provided livelihood for undocumented migrants in Japan were not helpful for keeping legal migrants, especially Fujian students in school. On the contrary, such social networks imposed on them both an extra financial burden and a social cost. From rural areas with few information channels about the regular procedures, Fujian immigrants mostly relied on “middle agencies” or “snakeheads” to process their visa applications. As a consequence, immigrants from Fujian paid a hefty fee for each successful visa application. And the more isolated the village was the more fees were demanded. One man from Fuzhou paid 1.2 million Japanese yen for his student visa including tuition. In comparison, a person from Changle who was the first person in his village to come to Japan paid 3 million yen within which 500 thousand yen was the middleman’s fee and another 500 thousand yen was deposit. His visa was obtained through his cousin who lived in the county seat and had a friend who was a snakehead. Prices commonly ranged from RMB 100,000 yuan (1.4 million yen) to 200,000 yuan (2.8million yen) from the mid-1990s to the early 2000s.7

Accompanying payment for the visa, there were also extra costs was associated with pooling money. Only a few families already had members working abroad and therefore could afford the initial costs. Most immigrant families borrowed at high interest (usually 1 percent every month) or obtained loans through rotating credit associations. Many Fujian students had to quit school and become visa-overstayers because of the financial burden.

|

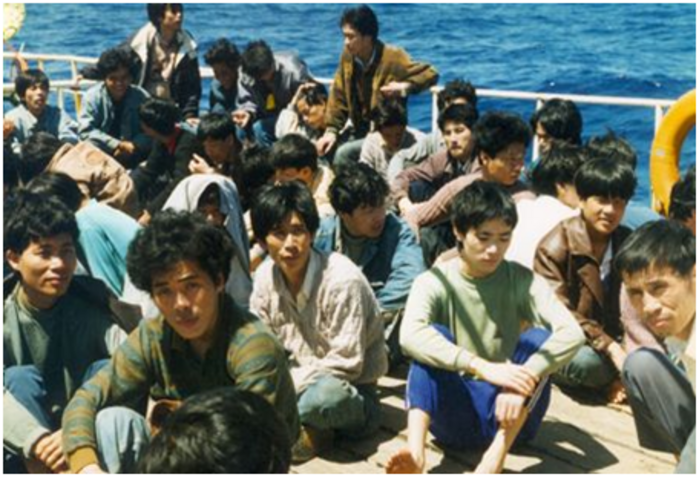

Fujian undocumented migrants on the deck of a fishing boat.

|

In summary, Fujian migration is frequently driven by economic motivation, especially the desire to accumulate capital and the pressure to pay off debts. The sense of relative deprivation also plays an important part in causing emigration. Moreover, the strong kinship-based social networks in Fujian not only facilitate migration but also sanction clandestine migration. In the following section, I explore Fujian undocumented migrants’ moral and ethical frameworks.

The Ethical Frameworks of Undocumented Fujian Migrants

In the summer of 2003, I spent several weeks in Fuqing City and Changle County, visiting repatriated informants and hoping to learn more about the communities. I was impressed by how normal clandestine migration was a part of economic and social life. Upon knowing that I would return to Japan, a Fuqing or Changle person would typically comment, “Oh, you have papers. My brother is there, but he has no papers.” Fujian Chinese immigrants are aware that human smuggling is a crime. However, it was not something people considered shameful to talk about. Having papers or not signals the degree of freedom instead of criminality. Even documented Fujian immigrants in Japan, while complaining about their reputations being tarnished by the clandestine migrants, show sympathy for their behavior. The justifications for undocumented migration out of Fujian typically fall into two categories—tradition and reciprocity.

Out-migration as a Tradition

In Fujian, the history of migration predates the emergence of nation-states. One informant offers the following explanation for the rampant undocumented migration out of that region.

… … if you wanted to know why there are so many people smuggled out of Fujian, you have to know the history of Fujian out-migration. Fujian had the most overseas Chinese. Along the coast, there was no good soil. Nothing grew there but yams. People were dirt poor. And many very poor people from Fujian, such as Lin Shaoliang, became rich overseas. Even now, it is still poor in many places there. Some islands don’t even have electric power. These rich overseas Chinese came back in the 1980s, investing in local industry and building things. The local people saw that, and believed that if they could go out they would a make fortune abroad. So going abroad is deeply rooted in Fujian people’s mentality.

The Fujian people I encountered loved to talk about the rags-to-riches story of the richest ethnic Chinese business person in the world, Lin Shaoliang, who left China for Indonesia in 1938, clandestinely. Fuqing city celebrates prominent overseas Chinese (huaqiao) like Lin, and plans to build a museum to document the migration history of this region. For the people living there, emigration is not only legitimate, but also glorious if you succeed.

Fuqing City, one of the main sending regions of migrants to Japan, boasts a population of 1.2 million, and 800,000 of them live overseas. Most local people have grandfathers or grand uncles living abroad. Out-migration in this region has a much longer history than the immigration control acts in all countries receiving Fujian immigrants.

Exchange and reciprocity as a moral principle

Aside from seeing migration, clandestine or not, as a traditional and historical means for achieving prosperity, Fujian undocumented migrants in Japan generally feel it is a fair exchange between them and Japanese society—they are selling their hard labor to make a better living. Fair exchange and reciprocity seem to be the leading ethical principles in the Fujian Chinese community. They take pride in being hard working and willing to eat bitterness, and feel their undocumented existence totally justified by their labor contribution to Japan. They frequently talk about how no Japanese young people are unwilling to do the jobs they are doing, to the degree that employers tried to protect them from being deported. At least in their immediate environment, their existence is considered legitimate and necessary. They resent the fact that they have become the object of apprehension. The most common narrative is “I am just working to earn a living here. I am not committing any crime.”One informant specifically interpreted the Japanese government’s crackdown on illegal foreign residents as a result of violent crimes committed by some Chinese migrants. He stated,

Many Fujian people like me work for Japanese restaurants, working very hard, working very properly in order to gain trust. There are bad people coming to Japan, joining the gangs……There are good and bad people, but the problem is that Japanese people swat all the Chinese with the same stick (yi bang da si). A friend of mine who was working in Ginza, not doing anything bad, was caught and sent back. He was just working conscientiously, but got sent back. It is like what the Guomindang used to say, “(I) would rather kill one innocent than let a guilty one escape (ningyuan cuosha yige, buyuan fangguo yige).”

Through reciprocity, Fujian migrants established trust and emotional bonds with employers and their family members. Shohei, who worked for a small Tsukiji company, lived next door to his boss, was given their family name, and was practically a member of the family. Yuki, who worked for a bakery owned by an old couple, was given gifts and “otoshi dama” and taken on trips to Hokkaido. Every week, she also helped the Okasan bathe the grandmother. Reports on employment of undocumented migrants tend to focus on the labor shortage and exploitation. However, given the social stigma attached to Fujian migrants, labor shortage and exploitation are necessary but not sufficient reasons to gain access to employment. Employers who have hired Fujian migrants are likely to hire more. Not only do the Fujian networks channel more fellow Fujian migrants into these jobs, but the phenomenon also creates bonds of trust.

Fujian migrants’ sense of exchange and reciprocity also shapes their attitudes toward many illicit activities in the underground world. Outside Fujian migrant society, the public talks about snakeheads or underground banks with horror. Snakeheads are consistently portrayed as exploiters, bullies and violent criminals. What surprised me most when I was in the Fujian migrant community was how naturally people talked about them. As mentioned before, the snakeheads the migrants have actual contacts with are often their kin. They are not necessarily loved. But Fujian people believe they offer an important service.

Most Fujian undocumented migrants also rely on underground banks to remit money. For undocumented migrants, the “underground bank” was what the Japanese government called it. It was simply a bank for the Fujian people. When asked about his opinion of underground banks, Atong commented that people who were running the bank were brave and were doing the Fujian people a service, because the Japanese government has tried to crack down on these illicit institutions. If the money was lost, he said, the bank operators would have to compensate the remitters for the loss.

Conclusion

Undocumented migration from Fujian has been considered both a puzzle and a threat to the rest of the world. When the tragedies in Dover and the Caribbean happened, and when organized crimes are attributed to gangs from Fujian, people and governments respond: “Why do they want to risk it all? How can we eliminate this?”

Using the case of undocumented migration from Fujian to Japan, this essay does not try to argue whether their practices are right or wrong. It merely provides some insights into the causes for their migration and the ethnical frameworks for their practices. Unfortunately, their ethics clash with the legal institution in the host society, which operates on a different set of principles. Questions remain. Do they have the right to pursue a historical means of survival? Although their presence is unauthorized, they are making fair exchanges with the host society and more often than not, reciprocate the benefits and gifts they receive. Some are involved in criminal activities. However, some of the crimes are by-products of the legal system itself, committed to make migration possible. Others, as in delinquencies by native citizens, are a manifestation of social marginalization.

This said, since I started fieldwork in 2002, I also sensed a change of norms in the Fujian immigrant community. This change was brought by the increasingly stringent immigration control by the Japanese government and the growing economic resources in immigrant sending areas. The Japanese government in recent years has stepped up deportation efforts, and increased inspection of illegal employment. This has made the life of undocumented immigrants in Japan much harder. Being undocumented was therefore increasingly considered an undesirable choice. Some interviewees coming in the mid-1990s turned undocumented without any regret, but those who lost status in the early 2000s wished they had had a second chance. While the majority of Fujian students who went to language school in the mid-1990s left school, one informant estimated that at least half of his classmates of 1998 class remained legal. Many younger Fujian immigrants were children of former migrants, therefore they had more financial resources than the earlier generation of immigrants.

However, several structural conditions of Japanese society as well as Fujian immigrants’ network characteristics might still contribute to visa overstaying. There remains a market niche for undocumented immigrants such as in construction and in restaurants. Secondly, although Japanese schools were recruiting more and more Chinese students, the Ministry of Justice had tightened inspection on schools and student visas. I started hearing about Fujian students who, although in school, were unable to renew their student visas. Given the tendency for Fujian students to choose obscure and expensive private schools with high acceptance rates (in some cases 100 percent) but lesser quality, some of them were bound to become undocumented in the new round of immigration control. Thirdly, the higher deportation rate resulting from recent campaigns against illegal immigration reinforced Fujian immigrants’ negative image both in Japan and among other Chinese, and aggravated their social isolation. Finally, the migration networks were still active and more and more people were coming in from Fujian. As in many Mexican villages, international migration has become a lifestyle. In particular, making money abroad has become a quick way to capital accumulation, especially when one faced debts from failed businesses. Although as an immigration destination, Japan might be less desirable than the US, coming to Japan remains significantly cheaper and the immigrant networks here are established.

Gracia Liu-Farrer is Associate Professor of Sociology at the Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies, Waseda University. She can be reached at [email protected]. She is the author of “Educationally Channeled International Labor Migration: Post-1978 Student Mobility from China to Japan,” International Migration Review, 43 (1),2009.1. 178-204, “Creating a Transnational Community: the Chinese Newcomers in Japan,” in Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity, (ed. Michael Weiner), and a forthcoming book titled Labor Migration from China to Japan.

Gracia Liu-Farrer wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Gracia Liu-Farrer, “Debt, Networks and Reciprocity: Undocumented Migration from Fujian to Japan,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 26-1-10, June 28, 2010.

References

Chin, Ko-Lin. 1999. Smuggled Chinese: Clandestine Immigration to the United States. Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

—-. 2001. “The Social Organization of Chinese Human Smuggling,” in D. Kyle and R. Espenshade, T. J. and D. Acevedo. 1995. “Migrant cohort size, enforcement effort, and the apprehension of undocumented aliens,” Population Research and Policy Review, 14: 145-172.

Cranford, Cynthia. 2005. “Networks of Exploitation: Immigrant Labor and the Restructuring of the Los Angeles Janitorial Industry.” Social Problems 52(3): 379-397.

Immigration Bureau, Ministry of Justice. 2007. Immigration Control. Tokyo.

Japan Immigration Association. 2004. Statistics on the Foreigners Registered in Japan.

Kwong, Peter. 1997. Forbidden Workers: Illegal Chinese Immigrants and American Labor. New York: New Press.

Liang, Zai and Wenzhen Ye. 2001. “From Fujian to New York: understanding the new Chinese immigration,” in D. Kyle and R. Koslowski (eds), Global Human Smuggling: Comparative Perspectives, Hohns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore: 187-215.

Liang, Zai and Hideki Morooka. 2004. “Recent Trends of Emigration from China: 1982-2000.” International Migration 43(3): 145-164.

—–, Miao David Chunyu, Guotu Zhuang and Wenzhen Ye. 2008. “Cumulative Causation, Market Transition,and Emigration from China,” American Journal of Sociology, Volume 114 Number 3 (November 2008): 706–37

Liu-Farrer, Gracia. 2008. “The Burden of Social Capital: Fujian Chinese Immigrants’ Experiences of Network Closure in Japan.” Social Science Japan Journal. Vol. 11 No. 22. 241-257

Massey, Douglas and J Arango, G. Hugo, A. Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino and J. Taylor. 1993. “Theories of international migration: a review and appraisal,” Population and Development Review 19(3). 431-466.

Ministry of Justice. Ministry of Justice Press Release, February 17, 2009, accessed on November 12, 2009.

Pieke, Frank N., Pal Nyiri, Mette Thuno, and Antonella Ceccagno. 2004. Transnational Chinese: Fujianese Migrants in Europe. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Tajima, Junko. 2003. “Chinese Newcomers in the Global City Tokyo: Social Networks and Settlement Tendencies.” International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 12: 68-78.

Vasishth, Andrea. 1997. “A model minority: the Chinese community in Japan,” pp. 108-139, in Japan’s Minorities: The Illusion of Homogeneity, ed. Michael Weiner. London: Routledge.

Notes

1 A shorter version of this paper titled “Ethics of Undocumented Migration” was published by Policy Innovations, and is based on a presentation of the same title at the Right to Move Conference held at Sophia University in January 2010.

2 This saying is cited by many articles on clandestine migration phenomenon in Fujian Province. Its Chinese version is: “台湾怕平潭,美国怕亭江,日本怕福清,英国怕长乐,全世界怕福建.” An example is the article “Luxurious Residences with No Men; Women’s Villages in Fujian ( 遍地豪宅不见男丁的福建”女人村” ) , http://www.huaxia.com/zk/sq/00095826.html, accessed on March 24, 2010.

3 Ministry of Justice Press Release, February 17, 2009, accessed on November 12, 2009.

4 URL, accessed on June 15, 2010.

5 Ministry of Justice Press Release, February 2009, URL, accessed on November 9, 2009.

6 In Japan, parents pay the hospital 300,000 to 600,000 yen for delivering a baby. Depending on the type of insurance, they usually receive about 300,000 yen from the government or an organization of which they are members. Because Japanese medical insurance cards do not have pictures attached to them, borrowing insurance cards at a fee was a common practice in the Fujian community. When delivering babies, they usually borrowed an insurance card and paid the hospital bill in cash. The insurance card holder could pocket the 300,000 yen from the government. Most undocumented Fujian immigrants also paid somebody, usually the card holder, 500,000 or more to take the baby back to China to their families.

7 In a region where average annual per capita income in 2003 was 3734 yuan (USD 466 or 50,000 yen) in rural areas and 10,000 (USD 1,250 or 140,000 yen) in cities and towns (National Bureauof Statistics of China 2004) 100 to 200 thousand yuan was a heavy burden.