Ampo’s Troubled 50th: Hatoyama’s Abortive Rebellion, Okinawa’s Mounting Resistance and the US-Japan Relationship

Gavan McCormack

This is the first of a three part comprehensive survey of the US-Japan relationship defined by the Ampo Treaty of 1960, and refined subsequently in ways that have deepened Japanese and Okinawan subordination to American global power and ambitions. The article focuses on questions pertaining to the legacy of Article Nine of the Constitution, and to Okinawa and base relations as a template for exploring the troubled Ampo relationship, including the powerful and sustained Okinawan resistance to US base expansion.

(Part 1)

“The natives on Okinawa are growing in number and are very anxious to repossess the lands they once owned.”

(President) Dwight Eisenhower, 19581

Ampo 50 – Ambiguous Celebration

On 19 January 2010, the Foreign and Defense Minsters of the US and Japan, in a statement to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the signing of the mutual treaty on cooperation and security, jointly declared that

“the U.S.-Japan Alliance plays an indispensable role in ensuring the security and prosperity of both the United States and Japan, as well as regional peace and stability. The Alliance is rooted in our shared values, democratic ideals, respect for human rights, rule of law and common interests. The Alliance has served as the foundation of our security and prosperity for the past half century and the Ministers are committed to ensuring that it continues to be effective in meeting the challenges of the twenty-first century.”2

The year of the “golden jubilee” anniversary of the US-Japan relationship in its current form should be an opportune time to reflect on it, continue it unchanged, straighten it out and revise it if necessary, or even end or replace it with something else. Instead, however, such reflection is blocked by a combination of shocking revelations of some and cover-up of other elements of the past record, pressure to revise in a certain way, and intense political hype. As the 50th anniversary loomed, the relationship headed towards a crisis potentially greater than any in the past that could threaten its future.

The 1960 “Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security” (commonly known, from the Japanese abbreviation, as Ampo), was adopted in 1960, replacing the 1951 San Francisco “Treaty of Peace with Japan,” which was the post-war settlement imposed by conqueror upon its defeated enemy in the wake of cataclysmic war and a six year occupation. Then “independence” had been restored only on condition of division of the country into “war state” (American-controlled Okinawa) and “peace state” (demilitarized and constitutionally pacifist mainland Japan), both under US military rule. The 1960 treaty upheld that division, confirming the US occupation of Okinawa and its use of bases elsewhere in the country.

The 1960 adoption of Ampo was tumultuous. The government at the time was that of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had been set up in part with CIA funds five years earlier and in character and inclination owed much to American patronage. It was headed from 1957 by Kishi Nobusuke, the US’s preferred agent, who had been installed as Prime Minister in 1957. Kishi rammed the bill through the House of Representatives in the pre-dawn hours on 20 May, in the absence of the Opposition, as protesters milled about in the streets outside.

|

Demonstrators surround the Diet in an attempt to bloc the Ampo Treaty |

After passage of the bill, President Eisenhower had to cancel his planned visit for fear of a hostile reception, and Kishi to resign. The then-US ambassador, Douglas MacArthur 2nd, reported to Washington on Japan as a country whose “latent neutralism is fed on anti-militarist sentiments, pacifism, fuzzy-mindedness, nuclear neuroses and Marxist bent of intellectuals and educators.”3 The memory of that 1960 crisis has deterred both governments from submitting the relationship to parliamentary or public review ever since.

Interventions and Secret Agreements

Prior to the renewal, during Kishi’s term in office, several agreements were struck that determined key aspects of the subsequent relationship. In 1959, the US government intervened to neutralize a Tokyo District Court judgement (the “Sunagawa Incident” case) in which Tokyo District Court Justice Date Akio held US forces in Japan to be “war potential” and therefore forbidden under the constitution’s Article 9 (the peace commitment clause). Had the Date judgement been allowed to stand, the history of the Cold War in East Asia would have had to take a different course. At 8 am on the morning immediately following it, however, and just one hour before the Cabinet was to meet, US ambassador Douglas MacArthur 2nd held an urgent meeting with Foreign Minister Fujiyama Aichiro.4 He is known to have spoken about the possible disturbance of public sentiment that the judgment might cause and the complications that might ensue. Following that meeting, the appeal process was cut short by having the matter referred directly to the Supreme Court, and MacArthur then met with the Chief Justice to ensure that he too understood what was at issue. In December 1959 the Supreme Court reversed the Tokyo Court judgement, ruling that the judiciary should not pass judgement on matters pertaining to the security treaty with the US because such matters were “highly political” and concerned Japan’s very existence.

|

Eisenhower with Kishi and Fujiyama (right) |

Following the Supreme Court ruling, the not-guilty verdicts in the initial hearings were reversed and the Sunagawa farmers were convicted of trespass in the course of their protest against compulsory acquisition of their land. The US intervention only became known more than 50 years later, from materials discovered in the US archives in April 2008. It was April 2010 before the Japanese Foreign Ministry released 34 pages of material to the surviving defendants of the 1959 action.5

The Supreme Court ruling, in effect elevating the Security Treaty above the constitution and immunizing it from any challenge at law, entrenched the US base presence and opened the path to the revision of the Security Treaty (and the accompanying secret understandings) a month later. It also helped remove wind from the sails of the then burgeoning anti-US Treaty movement. Denied recourse to the diet and the judiciary, the anti-war and anti-base struggle was forced into the streets.

Second were the series of agreements, later known in Japan as the “Secret Agreements” (Mitsuyaku), under which Japan (especially in 1958-1960 but also in 1969 and later) agreed to support US war preparations and nuclear strategy. With the memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still fresh in people’s minds, and that of the Daigo Fukuryu-maru (Lucky Dragon # 5) (1954) when Japanese tuna fishermen fell victim to radioactive ash from a US hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll, even fresher, no Japanese government could have survived if citizens had known how ready they were to embrace nuclear weapons. From time to time, however, there were revelations about these agreements. Documentary proof of them was found in the US archives, but successive Japanese governments persisted to 2009 in denying them. In 2008-9, however, four former Foreign Ministry vice-ministers gave evidence of the existence of the agreements and the deception surrounding them, so that it was impossible for the new Government to turn a blind eye to them any longer. Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya ordered a search of the archives for relevant materials on the mitsuyaku and his committee published its findings in March 2010.6 They confirmed three main understandings: first what they called a “tacit agreement” of the Government of Japan (January 1960) to turn a blind eye to US nuclear weapons, agreeing that “no prior consultation is required for US military vessels carrying nuclear weapons to enter Japanese ports or sail in Japanese territorial waters;”7 second, a “narrowly defined secret pact” to allow US forces in Japan a free use of the bases in the event of a “contingency” (i.e. war) on the Korean peninsula; and third, a “broadly defined secret pact” for Japan to shoulder costs for restoring some Okinawan base lands for return to their owners.8

|

Foreign Minister Okada (right) receives the secret report |

These findings were notable for what they excluded as well as for what they revealed. The 1960 nuclear agreement was first made public by US Admiral Gene Larocque in 1974 and confirmed by former Ambassador Edwin Reischauer in 1981, with the relevant documents found in the US archives in 1987.9 The Okada Committee did not accept the authenticity of the 21 November 1969 minute of an accord between Prime Minister Sato Eisaku and US President Richard Nixon to allow nuclear weapons into Okinawa in times of “great emergency,” even though it was recognized as “genuine” (for the reason that it turned up not in the archives but in the home of former Prime Minister Sato’s son).10 In a sense these agreements were therefore not intrinsically “secret” so much as kept secret, with the Government of Japan continuing up to 2009 to deny that they existed, presumably driven by fear of exposing to the Japanese people its complicity in nuclear war preparations that directly violated its proclaimed Three Non-Nuclear Principles.

The Committee chose to exclude from its “secret agreements” category other important agreements whose existence was known from US archival sources: notably the 1958 Japanese agreement to surrender jurisdiction over US servicemen accused of crimes in Japan,11 and (with one partial and limited exception) the 1969 secret agreements concerning the Okinawan “reversion” (discussed below).12

It is no mere matter of historical concern that the Government of Japan was secretly complicit in US nuclear war strategy by its consent to the US introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan, negating one of the country’s famous “Three Principles” (Non-Possession, Non- Production, Non-Introduction), and that the country’s nuclear policy has therefore long been based on deliberate deception at the highest level of government. In 2009, when President Obama made his Prague speech on the US’s “moral responsibility” to act to bring about a nuclear-free world, Japan responded by public support, and joined with Australia to sponsor a new global nuclear disarmament initiative, the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND). However, Japan’s national defense policy remained firmly nuclear, i.e., based on the “umbrella” of “extended nuclear deterrence” provided by the United States, and, behind the scenes, it pressed Washington to maintain it. One well-informed nuclear specialist refers to a “nuclear desiderata” document in which the Government of Japan (presumably in the late Aso Taro government period) urged Washington to maintain its nuclear arsenal, insisting that it be reliable (modernized), flexible (able to target multiple targets), responsive (able to respond speedily to emergencies), stealthy (including strategic and attack submarines), visible (with nuclear capable B-2s or B-52s kept at Guam), and adequate (brought to the attention of potential adversaries).13 The Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States (headed by William Perry and James Schlesinger), adopted very similar wording in advising Congress in May 2009 that “the United States requires a stockpile of nuclear weapons that are safe, secure, and reliable, and … credible.”14 One sentence in the report (p. 21) read, “One particularly important ally has argued to the Commission privately that the credibility of the U.S. extended deterrent depends on its specific capabilities to hold a wide variety of targets at risk, and to deploy forces in a way that is either visible or stealthy, as circumstances may demand (emphasis added). That “particularly important ally” is generally understood to refer to Japan.15 Schlesinger also told the Wall Street Journal that US nuclear weapons are needed “to provide reassurance to our allies, both in Asia and in Europe.”16

Although the term “umbrella” is innocuous, even comforting, it means that nuclear victim Japan is also nuclear dependent Japan, resting its defense on nuclear weapon capable B-2 and B-52 bombers stationed at Guam and on Cruise missile-carrying submarines, both ready to inflict nuclear devastation on an enemy just as the US did to it 65 years ago. And unless US nuclear submarines somehow are scrupulous in unloading their missiles before heading for Japanese ports, the likelihood is that the governments of the two countries continue today to connive, as through the past 50 years, to flout the “Three Non-Nuclear Principles,” while holding the Japanese people in contempt for their incorrigible “nuclear neuroses.”

Furthermore, the Diet Foreign Affairs Committee in March 2010 heard evidence from Togo Kazuhiko, a former Foreign Ministry official, to the effect that during his term as head of the Treaties Bureau in 1998-9 he had drawn up and handed to senior Ministry officials a set of 58 documents (16 of them of high level significance) on “secret agreements” in five red file boxes. Foreign Minister Okada’s Commission had discovered evidence relating to only eight (of which it confirmed only three). The obvious question is: where are the others now? Togo told the Diet that he “had heard” of a process of deliberate destruction that preceded the introduction of Freedom of Information legislation in 2001.17

In April 2010 a Tokyo District Court ordered the Foreign Ministry to locate and disclose documents concerning Okinawan “secret agreements,” even though the Ministry denied that it possessed any such documents. The court explicitly criticized the Ministry’s “insincerity” in “neglecting the public’s right to know,” and noted its suspicion that the Ministry might have deliberately destroyed sensitive documents in order to cover up the record.18 It was clear that there was much still to be done to clarify responsibility for Japan’s half century of lying to its people. Credibility and consistency in Japan’s contemporary nuclear disarmament policies also call for the record to be clarified.19

Half a century after Judge Date, Judge Sugihara Norihiko had taken a courageous stand in the same spirit. In 2010, the government waited just ten days before deciding to appeal. It means that public attention will continue through ongoing court proceedings to focus on the question of Foreign Ministry responsibility for the disappearance, if not the destruction, of official records of top-level negotiations.

Treaty? Alliance?

Two decades passed before the treaty relationship was described for the first time as an “alliance.” The use of the term in the Communiqué issued after the return of Prime Minister Suzuki Zenko from a visit to the White House in 1981 caused a furore. When Suzuki explained that he had not meant to suggest any military implications in the relationship, one Foreign Minister resigned and his successor issued the lame explanation that Communiqués were “not binding.” Suzuki was followed, however, by Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro, who defined the relationship in his memorable phrase describing Japan as the US’s “unsinkable aircraft carrier.” Gradually the terms “alliance” and “alliance relationship” became more common, although the actual term “Nichibei domei” (Japan-US Alliance” was only used in an official document for the first time in 1995.20 So the Treaty is fifty years old, but understanding of it as an “Alliance” is much younger.

The reservations over thinking of the treaty relationship as an “alliance” stem from its limitations. Strictly speaking, it is a narrow agreement for the defense of Japan (in the “Far East” according to Article 6). Although its terms have never been revised, its content and interpretation have been revised repeatedly. Late 20th century Japanese governments continually adjusted it by expanding its scope in practice, and early 21st century governments went further, setting aside legal and constitutional inhibitions in the struggle to meet American prescriptions for making it “mature,” which meant extending it into a global agreement for the combat against terror.21

From 2008, as the mandate of the LDP order shrank rapidly and DPJ support grew till in due course it formed a government the following year, details of the interventions and secret deals began to surface, casting a shadow over the anniversary celebrations. The anodyne and celebratory statements issued by official and semi-official sources on the occasion of the anniversary passed over the humiliating circumstances and near catastrophe of the “alliance’s” origin, the web of lies, deception and surrendered sovereignty that grew around and became inseparable from it. Instead, they celebrated the “alliance” as an unqualified good, to be deepened and strengthened.

Under the long, almost unbroken, era of LDP governments or LDP-centred coalitions, 1955-2009, there was only one occasion on which serious consideration was given to the possibility of a basic change in the US-Japan relationship. When conservative one party (LDP) government was briefly interrupted in 1993, Prime Minister Hosokawa appointed a Commission to advise on Japan’s post-Cold War diplomatic posture. Under the chairmanship of the head of Asahi Beer, Higuchi Kotaro, that Commission predicted the slow decline of US global hegemonic power and recommended Japan revise its exclusively US-oriented and essentially dependent diplomacy to become more multilateral, autonomous, and UN-oriented.22 In Washington, the “Higuchi Report” stirred anxiety. A US government commission headed by Joseph Nye (then Assistant Defense Secretary for International Security Affairs) shortly afterwards came to a diametrically opposite conclusion, advising President Clinton that since the peace and security of East Asia was in large part due to the “oxygen” of security provided by US forces based in the region, the existing defense and security arrangements should be maintained, the US military presence in East Asia (Japan and Korea) held at the level of 100,000 troops rather than wound down, and allies pressed to contribute more to maintaining them.23 Higuchi was thereafter forgotten, and the Nye prescription applied.

Although Nye’s frame of thinking was essentially paternalistic, arguing that East Asian peace, security and prosperity depended, and would continue to depend, on the “oxygen” provided by the US, LDP governments from then to 2009 did their best to accommodate to it, and to the subsequent detailed policy agendas drawn up by Nye in association with Richard Armitage and others in 2000 and 2007. Not until 2009 was there any serious questioning of the Nye formula.

Ampo and Okinawa

The 50th anniversary celebrations of the US-Japan “alliance” have a peculiar poignancy for Okinawa. Fifty years ago the Ampo treaty settlement simply confirmed its exclusion from “Japan,” its status under direct US military rule unchanged. With “Mainland Japan” a constitutional “peace state,” Okinawa served as the indispensable base for the prosecution of war in Korea, Vietnam (from the early 1960s), and in preparation for world war. The problem of how to reconcile the contradictory roles of mainland Japan and Okinawa confounds both governments to this day.

Okinawa’s post-war position as a kind of joint US-Japan condominium was peculiar from the outset, since the American occupation was at the express invitation and encouragement of no less a figure than the Showa emperor, Hirohito. It was his suggestion, in a September 1947 letter to General MacArthur, that Okinawa be leased to the US on a “twenty-five, or fifty-year, or even longer basis” to facilitate US opposition to communism, that helped crystallize the US decision to opt for a separate peace with Japan and to retain Okinawa as its military colony.24 Hirohito must have been at least in part moved by gratitude to General MacArthur for the assurance that he would be excused from trial as a war criminal and, indeed, continue as emperor. Thereafter, under direct US military jurisdiction until 1972, Okinawa’s raison d’être, for both Washington and Tokyo, was as centre for the cultivation of “war potential” and for the “threat or use of force” – both forbidden under Article 9 of the Japanese constitution.

When Okinawa was eventually “returned” to Japan in 1972, the process of “return” (henkan, or giving back) was one of a triple negation. Firstly, instead of a “giving back,” it was actually a “purchase.” Japan bought the islands from the US for a huge sum (most likely around $685 million),25 while allowing the US to retain virtually all its military assets and paying large ongoing fees since then to ensure that they not think of leaving. The payments included the sum of $70 million supposedly to remove nuclear weapons from Okinawa, but the chief negotiator on the Japanese side revealed nearly 40 years later that it was a groundless figure. “We decided on the cost to be able to say, ‘Since Japan paid so much, the nuclear weapons were removed.’ We did it to cope with opposition parties in the Diet.”26 A detailed accounting of the Okinawa “buy-back” remains to be done.

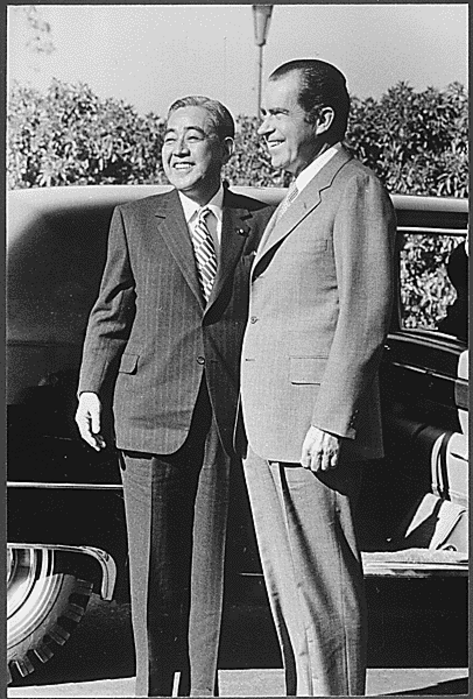

|

Sato and Nixon, 1972 |

Following the reversion, Japan from 1978 began to pay regular and continuing sums to subsidize the Pentagon, a peculiar form of “reverse rental” (by landlord to tenant) that came to be known as “omoiyari” (sympathy) payment in Japanese and “Host Nation Support” in English. The annual sum grew steadily, from 6 billion yen in 1978 to around 200 billion yen (more than $2 billion) today, with “indirect” items included, Japan’s subsidy in total amounted (according to the US Department of Defense in 2001) to an annual $4.4 billion.27 Over slightly longer than three decades, it amounts to approximately three trillion yen, roughly 35 billion dollars.28 That is about three times as much as NATO and about one half of the entire world’s subsidies to maintain the US military presence. Where other countries tend to “permit” US bases, often extracting substantial sums for so doing, Japan pays handsomely to persuade the US to continue, and not to reduce, its occupation.

Secondly, the real terms of the “return” (not just the fact of the payments) were carefully concealed. Though celebrated at the time as a diplomatic triumph for Prime Minister Sato Eisaku in securing return on terms of “kaku-nuki hondo-nami” (no nuclear weapons, exactly as mainland Japan) it was neither. Not only were the bases left intact but just two years after announcing the “Three Non-Nuclear Policies” Sato assured the US that it could continue introducing nuclear weapons into Okinawa, confiding to US ambassador Alexis Johnson that he thought the policy was “nonsense.”29 Five years later, he accepted the 1974 Nobel Peace Prize for having declared those very principles, despite his having covertly agreed to vitiate the principle of non-introduction. All Japanese governments from that time to 2009 persisted in lying to parliament and people by denying the existence of such an agreement. In 1999, the Japanese government even prevailed upon Washington to withdraw documents released under Freedom of Information in the US that exposed the secret nuclear deals and therefore also exposed the denial on which the government insisted as a lie.30 Obligingly, the US government withdrew the “open” classification.

Thirdly, despite the nominal inclusion of Okinawa from 1972 under the Constitution of Japan, with its guarantees of peace, democracy, and human rights, bitter experience has taught the Okinawans that in practice the principles of the security Treaty (including its secret elements), have always outweighed the constitution. The constitution in Okinawa from 1972 has been subject to the over-riding principle of priority to the military. Like North Korea, Okinawa is a “Songun” (priority to the military) state. LDP governments and foreign affairs and defense bureaucracies cultivated the belief that submission to the US (rather than the nominally supreme charter of the Constitution) was, and had to be, the first principle of the Japanese polity. The burden of that commitment fell especially on Okinawa.

There were many other heads under which Japan offered (and offers) financial backing for the US in its global military activities: from the $13 billion subsidy towards the costs of the Gulf War through subventions for subsequent wars down to the most recent Hatoyama pledge of 500 billion yen (ca $5.5 billion) over 5 years for civilian reconstruction works in Afghanistan. The Guam Treaty of February 2009 committed Japan to pay $6 billion “relocation costs” for housing, leisure and other facilities for the Marines on Guam, while the Henoko base construction, if it went ahead, was expected to cost at least 300 billion yen ($3.5 billion), and in unofficial but credible estimates more like one trillion yen ($11 billion). With Japan’s public debt (180 per cent in 2010) highest in the OECD, it is uncertain how much longer these sums can be shielded from budget cuts.

For Okinawa, reluctant host to major US Marine and Air Force facilities, one-fifth of the land surface of its main island still occupied by US forces nearly four decades after its “return” (or five decades since adoption of the Ampo treaty), the return of LDP governments from 1995, and the adoption of the Nye rather than the Higuchi vision, was therefore fateful. But where political and intellectual resistance to the Nye agenda crumbled nationally following the return to power in Tokyo of the LDP, it welled in Okinawa, especially after the shocking rape attack on a 12-year old girl by three GIs in 1995. As the LDP stumbled again in the late years of the first decade of the century, and an alternative government moved to assume power, it was the Okinawan periphery that set the agenda for the national debate on the country’s and the region’s future.

The Client’s Dilemma

I have referred elsewhere to the peculiar Japanese psychology of the “Client state”.31 In that state of chosen dependence the “client” embraces occupation, and is determined at all costs to avoid offence to the occupiers and ready to pay a huge price to be sure that it remains. It is a stratagem deeply entrenched in the Japanese state, followed by government after government and by national and opinion leaders. It is not a phenomenon unique to Japan, nor is it necessarily irrational. To gain and keep the favour of the powerful can often seem to offer the best assurance of security for the less powerful. Dependence and subordination during the Cold War brought considerable benefits, especially economic, and (with the important exception of Okinawa) the relationship was at that time subject to certain limits mainly stemming from the peculiarities of the American-imposed constitution (notably the Article 9 expression of commitment to state pacifism).

But as that era ended, instead of gradually reducing its military footprint in Japan and Okinawa as the “enemy” vanished, the US ramped it up, demanding a greater “defense” contribution from Japan and pressing for its Self Defense Forces to cease being “boy scouts” (as Donald Rumsfeld once contemptuously called them) and to become a “normal” army, able to fight alongside, and if necessary instead of, US forces and at US direction, in the “war on terror,” specifically in support of US wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It wanted Japanese forces to be integrated under US command, and it wanted greater access to Japan’s capital, markets and technology. While “Client State” status came to require heavier burdens and much increased costs in contrast to those borne during the Cold War, it offered greatly reduced benefits.

Even on the part of the LDP governments to 2009, discontent with the Nye prescription was slowly rising. Kyuma Fumio, a core LDP figure who rose to become Director-General of the Defense Agency and then Minister of Defense in the Abe government from September 2006, referred in 2003 to Japan as being just “like an American state.”32 Of the Iraq war, he later (2007) remarked that he might have expressed “understanding” of it, but never “support,”33 and of US base rights in Okinawa, that “we’re in the process of telling the United States not to be so bossy and let us do what we should do.”34 Even Aso Taro, when Foreign Minister in early 2007, referred to Donald Rumsfeld’s prosecution of the Iraq war as “extremely childish.”35

These, however, were occasional blips in the US-Japan relationship, dismissed as annoying gaffes,36 not affecting Tokyo’s continuing commitment to serve. The Democratic Party’s ascent to power was an altogether more serious matter, especially after its 2005 Manifesto declared a commitment to: “…do away with the dependent relationship in which Japan ultimately has no alternative but to act in accordance with US wishes, replacing it with a mature alliance based on independence and equality.”

That commitment was somewhat watered down as the party came closer to office, but with Hatoyama and his team still talking of “equality” and of renegotiating the relationship, Washington subjected them to a ceaseless flow of advice, demand and intimidation, pressing them to revert to the subservience that had become customary with the LDP.

As the credibility of the LDP faded and the star of the opposition Democratic Party of Japan rose in 2008-9, Joseph Nye emerged again at the heart of the Washington mobilization of pressure to neutralize the opposition before, and then again after, it took power. Nye issued two unmistakable warnings. In a Tokyo conference in December 2008, he spelled out the three acts that Congress would be inclined to see as “anti-American”: cancellation of the Maritime Self-Defense Agency’s Indian Ocean mission, and any attempt to revise the Status of Forces Agreement or the agreements on relocating US Forces in Japan [i.e. including the Futenma transfer].37 He repeated the same basic message when the Democratic Party’s Maehara Seiji visited Washington in the early days of the Obama administration to convey his party’s wishes to renegotiate these agreements, again warning that to do so would be seen as “anti-American.”38

The truth is that the US does not admit of “equality” in its relations with any other state. The role of Japanese Prime Minister is to manage a Washington “Client State.” The “closeness” and “reliability” of allies is measured by their servility. The words of Clare Short, looking back ruefully on her part in the Blair cabinet’s role in the war on Iraq, apply equally to Koizumi’s Japan: “We ended up humiliating ourselves [with] unconditional, poodle-like adoration” because the “special relationship” meant “we just abjectly go wherever America goes.”39

The Nye frame of thinking was essentially paternalistic, predicated on US military occupation continuing and based on distrust of Japan. Ota Masahide, who as Governor of Okinawa between 1990 and 1998 had occasion to deal with Nye from time to time, notes that Nye spoke of Okinawa as “like American territory” so that he (Ota) felt “inclined to ask him was it not part of the sovereign country, Japan.”40 Despite their overweening attitude, Nye and other “handlers” of the relationship were commonly respected, even revered, as “pro-Japanese.” Occasionally, however, a very different view was expressed. One well-placed Japanese observer recently wrote of the “foul odor” he felt in the air around Washington and Tokyo given off by the activities of the “Japan-expert” and the “pro-Japan” Americans on one side and “slavish” “US-expert” and “pro-American” Japanese on the other, both “living off” the unequal relationship which they had helped construct and support.41 Yet LDP governments, back in power from 1995, did their best to accommodate to the Nye prescription and its detailed extrapolation in the policy agendas of 2000 and 2007 drawn up in association with Richard Armitage and others.

In line with such thinking, the Obama administration could not tolerate the Hatoyama desire to re-negotiate the relationship with the United States so as to make it equal instead of dependent. For the Obama administration, as for that of George W. Bush, the model and high-point of the alliance would seem to be the golden era of “Sergeant-Major Koizumi” (as George W. Bush reportedly referred to the Japanese Prime Minister) when compliance was assured, annual US policy prescriptions (“yobosho”) were received in Tokyo as holy writ, and “slave-faced” expressions were fixed on the faces of Japanese bureaucrats, intellectuals, and media.

This is part one of a three part series written for the Asia-Pacific Journal on Ampo’s Troubled 50th Anniversary.

See part two here and part three here.

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, and author of many previous texts on Okinawa-related matters. His Client State: Japan in the American Embrace was published in English (New York: Verso) in 2007 and in expanded and revised Japanese, Korean, and Chinese versions in 2008. He is an emeritus professor of Australian National University.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, “Ampo’s Troubled 50th: Hatoyama’s Abortive Rebellion, Okinawa’s Mounting Resistance and the US-Japan Relationship (Part 1),” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 22-3-10, May 31, 2010.

Notes

1 DDE, “Memorandum for the Record,” 9 April 1958, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-60, vol. 18, p. 16

2 “Joint Statement of The U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Signing of The U.S.-Japan Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security,” January 19, 2010, by Minister for Foreign Affairs Okada, Minister of Defense Kitazawa, Secretary of State Clinton, Secretary of Defense Gates. Link.

3 Ambassador MacArthur to Department of State, Cable No 4393, 24 June 1960, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958-60, vol 18, pp. 377-384, at p. 380.

4 Odanaka Toshiki, “Shihoken dokuritsu e no oson kodo,” Sekai, August 2008, pp. 113-121. See also “Judicial independence infringed,” Japan Times, 3 May 2008.

5 “Sunagawa jiken no ‘Bei kosaku’ o itten kaiji, chunichi taishi to gaisho kaidanroku,” Tokyo shimbun, 3 April 2010.

6 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “Iwayuru ‘mitsuyaku’ mondai ni kansuru chosa kekka,” 9 March 2010.

7 “Record of discussion, 6 January 1960,” US National Archives, quoted in Akahata editorial, “Lay bare all secrets related to Japan-US Security Treaty,” Japan Press Weekly, 5 July 2009.

8 Togo Kazuhiko and Sato Masaru, “Gaimu kanryo ni damasareru Okada gaisho,” Shukan kinyobi, 26 March 2010, pp. 14-17.

9 Richard Halloran, “Sign of Secret U.S.-Japan Pact Found, New York Times, 7 April 1987; and on the 2008-9 confirmation from four former administrative vice foreign ministers , see national media for summer of 2009, especially Akahata, 22 June and 7 July 2009 (where some of the documents are reproduced). Also Honda Masaru, “Kensho: Kore ga mitsuyaku da,” Sekai, November 2009, pp. 164-175.

10 “Top Secret. Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato issued on November 21, 1969,” as discovered in 2009 by Sato’s son in his father’s papers, reproduced in Shunichi Kawabata and Nanae Kurashige, “Secret Japan-U.S. nuke deal uncovered,” Asahi shimbun, 24 December 2009 (link).

11 Kishi-MacArthur Agreement of 4 October 1958. (“Japan ‘ceded right to try US forces’ – secret accord ‘covers off-duty offenses’,” Yomiuri shimbun, 10 April 2010). The Okada Commission did not disclose this document, but it “surfaced” and was disclosed several weeks later. Professor Sakamoto Kazuya of Osaka University, is here cited as authority for the view that, fifty years on, this agreement still holds force.

12 Niihara Shoji, :Ampo joyaku ka no ‘mitsuyaku’,” Shukan kinyobi, 19 June 2009, pp. 20-21

13 Hans M. Kristensen, “Nihon no kaku no himitsu,” Sekai, December 2009, pp. 177-183, at p. 180.

14 US Institute of Peace, “Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States Issues Final report,” May 2009, pp. XV11-XV111.

15 A Kyodo report dated 30 July explicitly referred to Japanese pressure. See Narusawa Muneo, “Beigun no kaku haibi to Nihon,” Shukan kinyobi, 26 March 2010, pp. 18-19.

16 Melanie Kirkpatrick, “Why we don’t want a nuclear-free world,” Wall Street Journal, 13 July 2009.

17 “Mitsuyaku bunsho, doko e kieta,” Asahi shimbun, 20 March 2010.

18 “State told to come clean on Okinawa,” Asahi shimbun, 10 April 2010; Masami Ito, “Court: Disclose Okinawa papers,” Japan Times, 10 April 2010.

19 Togo Kazuhiko, testifying to the Diet Committee in 2010 on his role as head of the Treaty Bureau in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1998-99, “Mitsuyaku bunsho haki – kokumin to rekishi e no hainin da,” Tokyo shimbun, 20 March 2010. See also Togo’s discussion with Sato Masaru in “Gaimu kanryo ni damasareru Okada gaisho,” cit.

20 Maeda Tetsuo, “Juzoku” kara “jiritsu” e – Nichibei ampo o kaeru, Kobunken, 2009, p. 32.

21 See my Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, passim.

22 Boei mondai kondankai, “Nihon no anzen hosho to boeiryoku no arikata – 21 seiki e mukete no tenbo,” (commonly known as the “Higuchi Report” after its chair, Higuchi Kotaro), presented to Prime Minister Murayama in August 1994.

23 United States, Department of Defense, Office of International Security Affairs, “United States Security Strategy in the East Asia-Pacific Region” (commonly: “The Nye Report”), 27 February 1995.

24 The letter was penned by Hirohito’s aide, Terasaki Hidenari, but emanated from the emperor. (Shindo Eiichi, “Bunkatsu sareta ryodo,” Sekai, April 1979, pp. 31-51, at pp. 45-50.)

25 Client State, p. 158.

26 “Ex-negotiator: Cost to remove U.S. nukes from Okinawa exaggerated to dupe public,” Asahi shimbun, 13 November 2009.

27 Department of Defense, “US Stationed Military Personnel and Bilateral Cost Sharing 2001 Dollars in Millions – 2001 Exchange Rates,” Yoshida Kensei, “Ampo kichi no shima, Okinawa,” Oruta (Meru magajin), No 72, 20 December 2009, p. 10.

28 See the entry for “Omoiyari yosan” in Wikipedia (9 January 2009).

29 “Peace Prize winner Sato called nonnuclear policy ‘nonsense’,” Japan Times, 11 June 2000.

30 “99 nen Bei kokai no ‘kaku mitsuyaku’ bunsho Nihon saikimitsuka o yosei,” Asahi shimbun, 26 August 2009.

31 In the revised Japanese, Korean and Chinese editions of my 2007 book, Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, I offer the following definition: “a state that enjoys the formal trappings of Westphalian sovereignty and independence, and is therefore neither a colony nor a puppet state, but which has internalised the requirement to give preference to ‘other’ interests over its own.”

32 Asahi shimbun, 19 February 2003.

33 “Kyuma: U.S. invasion of Iraq a mistake,” Japan Times, 25 January 2007.

34 “Kyuma calls for Futenma review ‘Don’t be so bossy’, defense minister tells US over base relocation,” Yomiuri shimbun, 29 January 2007.

35 “Aso gaisho no Bei seiken hihan,” Asahi shimbun, evening edition, 5 February, 2007.

36 One former senior US government official commented: “staunch US allies such as Britain and Australia would never make such public criticisms.” (“Aso gaisho no Bei seiken hihan,” Asahi shimbun, evening edition, 5 February, 2007).

37 Quoted in Narusawa Muneo, “Shin seiken no gaiko seisaku ga towareru Okinawa kichi mondai,” Shukan Kinyobi, 25 September 2009, pp. 13-15.

38 Asahi shimbun, 25 February 2009. See also Maeda Tetsuo, “Juzoku” kara “jiritsu” e – Nichibei Ampo o kaeru, Kobunken, 2009, pp. 17, 25.

39 Clare Short, formerly International Development Secretary, “Clare Short: Blair misled us and took UK into an illegal war,” The Guardian, 2 February 2010.

40 Ota Masahide, interview, Videonews, 11 March 2010. Transcript at “Peace Philosophy,” 12 April 2010.

41 Terashima Jitsuro, “Zuno no ressun, Tokubetsu hen, (94), Joshiki ni kaeru ishi to koso – Nichibei domei no saikochiku ni mukete,” Sekai, February 2010, 118-125. Terashima refers to Japanese intellectuals by the term, “do-gan” (literally “slave face”, a term he invents based on his reading of a savagely satirical early 20th century Chinese story by Lu Hsun). For English translation of this Terashima text, see “The Will and Imagination to Return to Common Sense: Toward a Restructuring of the US-Japan Alliance,” The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, 15 March 2010.