The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty (Japanese text available)

Gavan McCormack

“It is incredible how as soon as a people become subject, it promptly falls into such complete forgetfulness of its freedom that it can hardly be roused to the point of regaining it, obeying so easily and so willingly that one is led to say that this people has not so much lost its liberty as won its enslavement.”

Etienne de la Boétie (1530-1563). Discours de la servitude volontaire ou le Contr’un (Discourse on Voluntary Servitude, or the Anti-Dictator).[1]

For a country in which ultra-nationalism was for so long a problem, the weakness of nationalism in contemporary Japan is puzzling. Six and a half decades after the war ended, Japan still clings to the apron of its former conqueror. Government and opinion leaders want Japan to remain occupied, and are determined at all costs to avoid offence to the occupiers. US forces still occupy lands they then took by force, especially in Okinawa, while the Government of Japan insists they stay and pays them generously to do so. Furthermore, despite successive revelations of the deception and lies (the secret agreements) that have characterized the Ampo relationship, one does not hear any public voice calling for a public inquiry into it. [2] Instead, on all sides one hears only talk of “deepening” it. In particular, the US insists the Futenma Marine Air Station on Okinawa must be replaced by a new military complex at Henoko, and with few exceptions politicians and pundits throughout the country nod their heads.

Okinawa in the East China Sea. Why the Ryukyus are the “Keystone of the Pacific” for US strategic planners

Chosen dependence is what I describe as Client State-ism (Zokkoku-shugi). [3] It is not a phenomenon unique to Japan, nor is it necessarily irrational. To gain and keep the favor of the powerful, dependence can often seem to offer the best assurance of security for the less powerful. Dependence and subordination during the Cold War brought considerable benefits, especially economic, and the relationship was at that time subject to certain limits, mainly stemming from the peculiarities of the American-imposed constitution (notably the Article 9 expression of commitment to state pacifism).

But that era ended, and instead of gradually reducing the US military footprint in Japan and Okinawa as the “enemy” vanished, the US decided to ramp it up. It pressed Japan’s Self Defence Forces to cease being “boy scouts” (as Donald Rumsfeld once contemptuously called them) and to become a “normal” army, able to fight alongside and if necessary instead of, US forces and at US direction, in the “war on terror,” specifically in support of US wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan. It wanted Japanese forces to be integrated under US command, and it wanted greater access to Japan’s capital, markets and technology. “Client State” status required heavier burdens and much increased costs than during the Cold War, but it offered greatly reduced benefits.

Ever since the Hatoyama team first showed signs of being likely to assume government, and talked of “equality” and of renegotiating the relationship, Washington has maintained a ceaseless flow of advice, demand and intimidation to push it into the kind of subservience that had become the norm. The same “Japan experts” and “Japan-handlers” that in LDP times offered a steady stream of advice to “show the flag,” “put boots on the ground” in Iraq, and send the MSDF to the Indian Ocean, now send a steady drumbeat of: Obey! Obey! Obey! Implement the Guam Treaty! Build the new base at Henoko!

Yet, with the important exception of Okinawa, there is little sign of outrage in Japan. Instead, US demands are echoed by a chorus of Japanese voices agreeing that Hatoyama and his government be “realistic.” One well-placed Japanese observer recently wrote of the “foul odor” he felt in the air around Washington and Tokyo given off by the activities of the “Japan-expert” and the “pro-Japan” Americans on one side and “slavish” “US-expert” and “pro-American” Japanese on the other, both “living off” the unequal relationship which they had helped construct and support.[4]

Another recent Japanese critic, quoting the passage from de la Boétie that prefaces this article, writes:

“Struggling to be ‘best’ under the American umbrella, and taking it as matter for pride when cared for by the US, has become a structure in which ‘servitude’ is no longer just a necessary means but is happily embraced and borne. ‘Spontaneous freedom’ becomes indistinguishable from ‘spontaneous servitude’.” [5]

As the security treaty in its current form marks its 50th anniversary in 2010, it should be possible to reflect on the relationship, to continue it unchanged, straighten it out and revise it if necessary, or even to end it, but such reflection is blocked by a combination of cover-up of the past record, one-sided pressure to revise in a certain way, and political hype and rhetoric. As a result, in the year of the “golden Jubilee” anniversary, a more unequal, misrepresented and misunderstood bilateral relationship between two modern states would be difficult to imagine.

Although Hatoyama called for an “equal” relationship, the truth is that the US state does not admit the possibility of equality in its relations with any other state. The “closeness” and “reliability” of an ally is simply a measure of its servility. According to one senior member of the cabinet of Britain’s Tony Blair, looking back on her Government’s role in the war on Iraq, despite being the US’s supposedly closest of allies, “We ended up humiliating ourselves [with] unconditional, poodle-like adoration” because the “special relationship” meant “we just abjectly go wherever America goes.”[6] Her words deserve to be taken seriously by all America’s allies.

Only twice have Japanese governments made an effort to think of an alternative to the dependence rooted in the treaties of 1951 (San Francisco) and 1960 (Ampo) that have formed the legal frame for the post-Occupation relationship. In 1994 the Higuchi Commission recommended to Prime Minister Murayama Tomiichi that Japan revise its exclusively US-oriented, dependent diplomacy to become more multilateral, autonomous, and UN-oriented. [7] However, a US government commission headed by Joseph Nye then advised President Clinton almost precisely the opposite: since the peace and security of East Asia was in large part due to the “oxygen” of security provided by US forces based in the region, the existing defence and security arrangements should be maintained, the US military presence in East Asia (Japan and Korea) held at the level of 100,000 troops rather than wound down, and allies pressed to contribute more to maintaining them. Higuchi was forgotten and the Nye prescription applied. Not until 2009 was there any serious questioning of the wisdom of the Nye formula.

It was Nye and his associates (notably Richard Armitage) who from 1995 drew up the detailed sets of post-Cold War policy prescriptions for Japan. Paradoxically, but also reflecting the “Client State” phenomenon, they came to be respected, even revered, as “pro-Japanese” or “friends of Japan.” They and their colleagues drew the 2000 goal (in the “Armitage-Nye Report”) of turning the relationship into a “mature” alliance by reinforcing Japanese military subordination and integration under US command, removing barriers to the active service of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces on “collective security” missions, and taking the necessary steps towards revising the constitution, and in 2007 the further agenda of strengthening the Japanese state, revising the (still unrevised) constitution, passing a permanent law to authorize regular overseas dispatch of Japanese forces, and stepping up military spending.[8] The agreements on relocating US Forces in Japan (Beigun saihen, 2005-6) and Guam Treaty (2009) were the detailed policy instruments towards those goals. The “Futenma Replacement” (Henoko) project formed a central plank.

As Hatoyama’s team began to talk of equality and of an Asia-Pacific Community, it was Joseph Nye who issued a series of warnings, first spelling out (in December 2008) the acts that Congress would be inclined to see as “anti-American,” prominent among them being any attempt to revise the Beigun Saihen agreements (including the Futenma transfer).

The Treaty system whose anniversary is celebrated in 2010 has been unequal throughout its 50 years and is encrusted with deception and lies. The 1960 Treaty, rammed through the Diet in the pre-dawn hours and in the absence of the opposition, reconfirmed the (1951) division of the country into a demilitarized mainland “peace state” Japan and a directly American-controlled Okinawan “war state.” That division was maintained even when, in 1972, Okinawa was restored to nominal Japanese administration, in a deal that was also a model of deception. Firstly, the Okinawa “return” was in fact not a “giving back” but a “purchase,” Japan paying the US even more (for “return” of assets that in fact the US military retained) than it had paid seven years earlier to South Korea in compensation for forty years of colonial rule. And secondly, although the deal was declared to be one of reduction of Okinawan bases to mainland levels and without nuclear weapons, “kaku-nuki hondo-nami,” it was neither. The “war state” function remained central, bases remained intact and the US was assured (in the secret agreement, or mitsuyaku) that its nuclear privilege would remain intact. Despite the nominal inclusion of Okinawa under the Japanese constitution, then and since it has continued in fact to be subject to the over-riding principle of priority to the military, that is, the US military, and in that sense, ironically, matching North Korea as a “Songun” state.

Both governments prefer secret diplomacy to public scrutiny. By simple bureaucratic decision, Japan instituted a system of subsidy for US wars known as the “omoiyari” (sympathy) payments and expanded the scope of the security treaty from Japan and the “Far East” (according to Article 6) into a global agreement for the combat against terror. “Client State” Japan pays the US generously to continue, and not to reduce, its occupation.[9]

In mainland Japan, political and intellectual resistance to the Nye Client State agenda for Japan quickly crumbled nationally from 1995 with the return to power in Tokyo of the LDP, and the qualities of nationalism, democracy and constitutionalism were gradually relegated to second place to the “higher” cause of the alliance. In Okinawa, however, forced to bear the brunt of US military rule, civil democracy in the form of anti-base resistance grew steadily and the Client State agenda was never able to attain legitimacy. Consequently, for 14 years, through the terms of 8 Prime Ministers and 16 Defense Ministers, the 1996 bilateral agreement to substitute a Henoko base for the Futenma one made no progress. It was blocked by the fierce, uncompromising, popularly-supported Okinawan resistance.

In 2005 Okinawan civil society won an astonishing, against all odds, victory over the Koizumi government and its US backers, forcing the Government of Japan to abandon the “offshore” (on-reef, floating, pontoon structure) Henoko base project. It was a historic event in the history of democratic and non-violent civic activism. The government returned to the offensive in 2006, however, with its design for an enlarged, “on-shore” Henoko base to be built on reclaimed land that would jut out into Oura bay from within the existing Camp Schwab marine base. This dual runway, hi-tech, air, land and sea base able to project force throughout Asia and the Pacific was far grander and more multifunctional than either the obsolescent, inconvenient and dangerous Futenma or the earlier offshore, pontoon-based “heliport.”

Oura Bay

Though widely reported (with the subterfuge that is characteristic of the “Alliance”) as a US “withdrawal” designed to reduce the burden of post-World War II American military presence in Okinawa, the 2006 agreement would actually further the agenda of integration of Japanese with US forces and subjection to Pentagon priorities and increase the Japanese financial contribution to the alliance (with Japan paying $6.1 billion for US marine facilities on Guam and up to $10 billion for a new Marine Base at Henoko). “Consolidation” and “reinforcement” were the appropriate terms.

When Obama took office in early 2009, his Japan expert advisers seem to have advised him to move quickly to pre-empt any possible policy shift under a future DPJ government. They therefore exploited the interval when the LDP still enjoyed the two-thirds Lower House majority delivered by Koizumi’s “postal privatization” triumph of 2005 to press the 2006 agreement into a formal treaty and had Prime Minister Aso ram it through the Diet (in May 2009), so as to tie the hands of the Democratic Party forces about to be elected to government.

The Guam Treaty of 2009 was a defining moment in the US-Japan relationship, when both parties went too far, the US in demanding (hastily, well aware that time was running out to cut a deal with the LDP) and Japan in submitting to something not only unequal (imposing obligations on Japan but not on the US), but also unconstitutional, illegal, colonial and deceitful. [10] Yet few Japanese seemed able to detect the “foul odor” that arose from the deal.

In Okinawa, however, the Hatoyama DPJ election victory of August 2009, marked not only by the national party’s electoral pledge to relocate the Futenma base outside the prefecture but by the clean sweep within the prefecture of committed anti-base figures, was taken as signalling that a new and favourable tide to Okinawa was rising. Opposition to any “within Okinawa” Futenma relocation became almost total across the political spectrum. When a committed anti-base candidate was elected mayor of Nago City on 24 January 2010, the threat to Oura Bay (and its dugong, coral and turtles) seemed drastically diminished. Having witnessed the lies and deceptions by which over 13 years the temporary, pontoon-supported “heliport” gradually evolved into the giant, reclamation, dual-runway and military port project of 2006, and having experienced the emptiness of the promise of economic growth in return for base submission, Okinawans were in no mood to be tricked again.

Author being briefed at the site of the Helipad Sit-In, Higashi village, Yambaru, Okinawa, 6 December 2009.

If the two elections gave great heart to Okinawans, however, they also shook the “alliance” relationship. Washington insisted on fulfilment of the Guam Treaty but the Henoko base could only now be built if Hatoyama was prepared to adopt anti-democratic measures of something akin to martial law to defy the will of Okinawan voters and protesters. That would be a peculiar way to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the “Alliance.”

At Honolulu in January 2010, Hillary Clinton insisted that the Ampo base system was indispensable for East Asian, especially Japan’s, security and prosperity. It was essentially Joseph Nye’s 1995 point. But is it true? The idea that the peace and security of East Asia depends on the presence of the Marines in Okinawa (the “deterrence” function) is tendentious. There is today almost zero possibility of an attack on Japan by some armed force such as was imagined during the Cold War, and in any case the Marines are an expeditionary “attack” force, held in readiness to be launched as a ground force into enemy territory, not a force for the defense of Okinawa or Japan as stipulated under Article 4 of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security. Since 1990, they have flown repeatedly from bases in Japan for participation in the Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Wars.

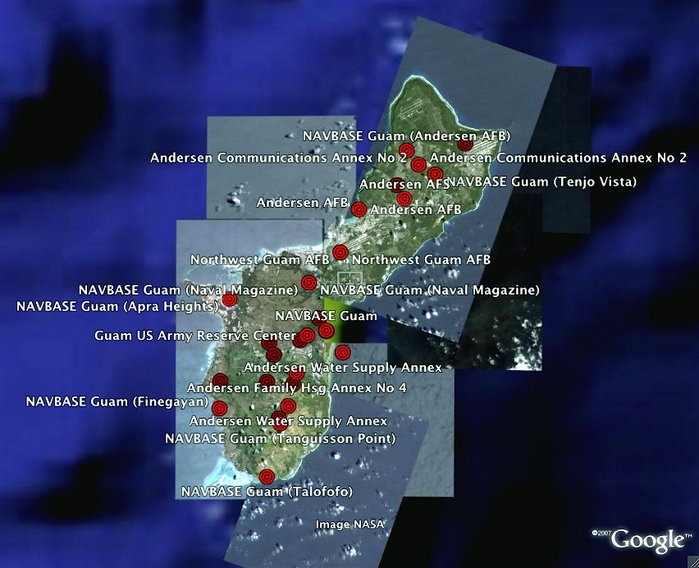

Furthermore, the hullabaloo in Japan surrounding the Henoko project rests on a serious misunderstanding. As Ginowan City mayor, Iha Yoichi, has repeatedly shown from his analysis of US military planning documents, the Pentagon from 2006 has been committed to transfer main force Futenma marine units to Guam, upgrading it into the military fortress and strategic staging post covering the whole of East Asia and the Western Pacific (and thus undercutting the strategic importance of any new Okinawan base). [11] Iha’s analysis was at least partially confirmed by a senior official of Japan’s defense bureaucracy who described the 3rd Marine Division as a “force for deployment at any time to particular regions beyond Japan …. not for the defense of particular regions.” [12] In short, the Guam Treaty is concerned not with a Futenma substitute, or even with the defense of Japan, but with construction of a new, upgraded, multi-service facility that U.S. Marines will receive for free and will use as a forward base capable of attacking foreign territories.

US military footprint on Guam

Virtually without exception, American officials, pundits and commentators support the Guam treaty formula and show neither sympathy nor understanding for Japanese democracy or Okinawan civil society, and by and large the Japanese pundits and commentators respond to this in “slave-faced” manner (do-gan in Terashima’s term). The Okinawa Times (19 January 2010) notes that the 50th anniversary offered a “chance to reconsider the Japan-US Security treaty that from Okinawa can only be seen as a relationship of dependence.” To seriously “re-consider” would require wiping the “slave faces” off Japan’s politicians and bureaucrats.

Hatoyama’s government has enunciated idealistic sentiments – including statements such as from Party Secretary-General Ozawa Ichiro saying that “Okinawa beautiful blue seas must not be despoiled” [13], and the postponing of a decision on the Futenma issue to May opened the issue to a measure of public scrutiny and discussion. However, neither the Prime Minister nor any of his senior ministers offered leadership or did anything to encourage discussion on the nature of the alliance or Okinawa’s burdens. Instead, the Hatoyama government backed itself into a corner by assuming the legitimacy of the Guam Treaty, from which it followed that Futenma could not be returned unless or until it was replaced. Furthermore, prominent ministers, in “Client State” spirit, publicly identified with the position of the US government. Thus Foreign Minister Okada in Nago on 5 December 2009 pleaded with Okinawans to understand the “crisis of the alliance” and the “difficulty” of the negotiations. He suggested that Okinawans should have sympathy for President Obama “who might not be able to escape criticism for weakness in his dealings with Japan at a time of falling popularity” if the Guam Treaty deal was not implemented. [14]

When Hatoyama announced the postponement of decision till May 2010, a Pentagon Press Secretary declared that the US “did not accept” the Japanese decision, [15] and Joseph Nye referred to the DPJ as “inexperienced, divided and still in the thrall of campaign promises,” plainly meaning that attempts to renegotiate the Guam Agreement would not be tolerated. [16]

Yet, the mood in Okinawa unquestionably strengthened following the Hatoyama victory and the sweeping aside of the representatives of the “old regime” in Okinawa in August 2009. Opinion polls had long shown levels of around 70 per cent against the Guam formula (for Henoko construction), [17] but that figure rose steadily, so that one May 2009 survey found a paltry 18 per cent in favour of the Henoko option on which Washington was adamant, and by November that figure had fallen to 5 per cent; hardly anyone. [18] Both Okinawan newspapers, and the most prominent figures in Okinawan civil society, were strongly opposed. [19] The signals of anger and discontent rose to their peak in February 2010 with the adoption by the Okinawan parliament (the Prefectural Assembly) of an extraordinary resolution, unanimously demanding that Futenma be closed (moved “overseas or elsewhere in Japan”), [20] and Okinawa’s 41 local district mayors also unanimously declared themselves of the same view. [21]

It meant that, while Tokyo struggled desperately to find a way to implement the Guam Treaty, Okinawa unanimously rejected it. There is no longer a “progressive-conservative” divide in Okinawan politics on this question. The Mayor of Okinawa’s capital, Naha, who in the past served as President of the Liberal Democratic Party of Okinawa, recently made clear that, as a prominent Okinawan conservative, he was disappointed by the Hatoyama government’s reluctance to redeem its electoral pledge on Futenma and hoped the Okinawan people would remain united “like a rugby scrum” to accomplish its closure and return (i.e., not replacement). [22] No local government or Japanese prefecture in modern history had ever been at such odds with the national government.

Early in March, Defense Vice-Minister Nagishima Akihisa bluntly declared that the US demands would be met, even if it meant alienating Okinawans (who would be offered “compensation.”) [23] With Hatoyama likewise insisting that he would honour alliance obligations, and the likelihood high that other formulas would prove unworkable or impossible to clear in such a tight timetable, Okinawans braced themselves. By May, 2010 Hatoyama would have to either reject the US demands, risking a major diplomatic crisis, or submit to them, announcing with regret that there is no “realistic alternative” to the “V-shaped” base at Henoko, thus provoking a domestic political crisis.

While official 50th anniversary commemorations celebrate the US military as the source of the “oxygen” that guaranteed peace and security to Japan, it is surely time for Japanese civil society to point out that the same oxygen is elsewhere a poison, responsible for visiting catastrophe in country after country in East Asia and beyond, notably Korea (1950s and since), Iran (1953), Guatemala (1954), Vietnam (1960s to 70s), Chile (1973), the Persian Gulf (1991), Afghanistan (2001-), and Iraq (2003-), and that now threatens Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen, and (again) Iran. Millions die or are driven into exile, and countries are devastated as the US military spreads its “oxygen” by unjust, illegal and ruthless interventions and permanent occupations. The degree to which allied countries share criminal responsibility has been the subject of major public review in Holland (which found that the Iraq War was indeed illegal and aggressive) and in the UK (where the Chilcot Inquiry continues). It is time for similar questions to be asked in Japan of the Iraq and Afghan wars, and Japan’s direct and indirect involvement in them.

The 50th anniversary should be a time for the Japan whose constitution outlaws “the threat or use of force in international affairs” to reflect on how it has come to rest its destiny on alliance with the country above all others for whom war and the threat of war are key instruments of policy, and whether it should continue to offer unqualified support and generous subsidy, and whether it should continue to “honour” the Guam treaty, at all costs maintaining the marine presence in Okinawa. As a first step, it is time to debate openly the unequal treaties, secret diplomacy, lies, deception and manipulation of the last 50 years and time to reflect upon, apologize, and offer redress for the wrongs that have for so long been visited upon the people of Okinawa as a result.

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator of The Asia-Pacific Journal – Japan Focus, and author of many previous texts on Okinawa-related matters. His Client State: Japan in the American Embrace was published in English (New York: Verso) in 2007 and in expanded and revised Japanese, Korean, and Chinese versions in 2008. He is an emeritus professor of Australian National University. The present paper is an expanded version of his article published in Japanese in Shukan kinyobi on 5 March 2010.

Recommended citation: Gavan McCormack, “The Travails of a Client State: An Okinawan Angle on the 50th Anniversary of the US-Japan Security Treaty,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 10-3-10, March 8, 2010.

See the following articles on related themes:

Kikuno Yumiko and Norimatsu Satoko, Henoko, Okinawa: Inside the Sit-In

Urashiima Etsuko and Gavan McCormack, Electing a Town Mayor in Okinawa: Report from the Nago Trenches

Tanaka Sakai, Japanese Bureaucrats Hide Decision to Move All US Marines out of Okinawa to Guam

Gavan McCormack, The Battle of Okinawa 2009: Obama vs Hatoyama

Hayashi Kiminori, Oshima Ken’ichi and Yokemoto Masafumi, Overcoming American Military Base Pollution in Asia: Japan, Okinawa, Philippines

See also, the Peace Philosophy Center, particularly the two articles posted on March 16, 2010 entry on recent plans for a new offshore base and plans for a naval base and casino. The blog is an important and regularly updated source of information in Japanese and English on Okinawan and US-Japan developments and issues of war and peace in the Asia-Pacific. It is available here: http://peacephilosophy.com

Notes

[1] In English as The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude, translated by Harry Kurz and with an introduction by Murray Rothbard, Montrèal/New York/London: Black Rose Books, 1997. Web version here. I am indebted to Nishitani Osamu (see note 5) for drawing my attention to de la Boétie.

[2] Foreign Minister Okada Katsuya did set up an “Experts” committee to investigate the so-called “Secret Agreements” between US and Japanese governments on nuclear and other matters and report back during 2010, but it was of limited focus, precipitated by the common knowledge that such documents existed in the US archives and a series of public statements by former senior officials testifying to their existence. Early reports from Tokyo suggest that no such documents had been found, which raised the possibility they had been deliberately destroyed.

[3] Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, New York, Verso, 2007. Expanded Japanese edition as Zokkoku – Amerika no hoyo to Ajia de no koritsu, Tokyo, Gaifusha, 2008.

[4] Terashima Jitsuro, “Zuno no ressun, Tokubetsu hen, (94), Joshiki ni kaeru ishi to koso – Nichibei domei no saikochiku ni mukete,” Sekai, February 2010, 118-125. Terashima refers to Japanese intellectuals by the term, “do-gan” (literally “slave face”, a term he invents based on his reading of a savagely satirical early 20th century Chinese story by Lu Hsun).

[5]. Nishitani Osamu, “’Jihatsuteki reiju’ o koeyo – jiritsuteki seiji e no ippo,” Sekai, February 2010: pp. 134-140, at p. 136.

[6] Clare Short, formerly International Development Secretary, “Clare Short: Blair misled us and took UK into an illegal war,” The Guardian, 2 February 2010.

[7] Boei mondai kondankai, “Nihon no anzen hosho to boeiryoku no arikata – 21 seiki e mukete no tenbo,” (commonly known as the “Higuchi Report” after its chair, Higuchi Kotaro), presented to Prime Minister Murayama in August 1994.

[8] Richard L. Armitage and Joseph S. Nye, “The U.S.-Japan Alliance: Getting Asia right through 2020,” Washington, CSIS, February 2007.

[9] For details, see my Client State, passim.

[10] “The Battle of Okinawa 2009: Obama vs Hatoyama,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 16 November 2009.

[11] “Why Build a New Base on Okinawa When the Marines are Relocating to Guam?: Okinawa Mayor Challenges Japan and the US.” See also Iha Yoichi, interviewed in “Futenma isetsu to Henoko shin kichi wa kankei nai,” Shukan kinyobi, 15 January 2010, pp. 28-9.

[12] Yanagisawa Kyoji (special researcher and former Director of National Institute for Defense Studies), “Futenma no kakushin –kaiheitai no yokushiryoku o kensho seyo,” Asahi shimbun, 28 January 2010.

[13] “Santo raigetsu isetsusaki oteishi,” Okinawa Times, 29 December 2009.

[14] Quoted in “Kiki aoru dake de wa nasakenai,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 7 December 2009. For a fascinating transcript of the meeting, see Medoruma Shun’s blog, “Uminari no hitobito,” “Okada gaisho to ‘shimin to no daiwa shukai’, zenmen kokai,” in 7 parts, beginning here.

[15] “Pentagon prods Japan on Futenma deadline,” Japan Times, 8 January 2010.

[16] Joseph S. Nye Jr, “An Alliance larger than One Issue,” New York Times, 6 January 2010.

[17] “Futenma hikojo daitai, kennai isetsu hantai 68%,” Okinawa Times, 14 May 2009. In the Northern Districts (including Nago Ciy) opposition was even higher, at 76 per cent.

[18]“Futenma iten: Genko keikaku ni ‘hantai” 67%, Okinawa yoron chosa,” Mainichi shimbun, 2 November 2009; for a partial English account, “Poll: 70 percent of Okinawans want Futenma moved out of prefecture, Japan,” Mainichi Daily News, 3 November 2009.

[19] Open Letter to Secretary of State Clinton, by Miyazato Seigen and 13 other representative figures of Okinawa’s civil society, 14 February 2009, (Japanese) text at “Nagonago zakki,” Miyagi Yasuhiro blog, 22 March 2009; English text courtesy Sato Manabu. They demanded cancellation of the Henoko plan, immediate and unconditional return of Futenma, and further reductions in the US military presence.

[20] “Kengikai, Futenma ‘kokugai kengai isetsu motomeru’ ikensho kaketsu,” Okinawa Times, 24 February 2010. A resolution to the same effect had been passed by a majority in July 2008.

[21] “Zen shucho kennai kyohi, Futenma kengai tekkyo no shiodoki,” editorial, Ryukyu shimpo, 1 March 2010. The rising tide of Okinawan sentiment on this issue is plain from the fact that the figure had been 80 per cent, or 31 out of the 41 mayors, in October “Futenma ‘kengai’ ‘kokugai’ 34 nin,” Okinawa Times, 30 October 2009).

[22] Onaga Takeshi, “Okinawa wa ‘yuai’ no soto na no ka,” Sekai, February 2010, pp. 149-154.

[23] John Brinsley and Sachiko Sakamaki, “US base to stay on Okinawa, Japanese official says,” Bloomberg, 2 March 2010.