Gavan McCormack

It is a commonplace of recent writing on Japan that the Abe Shinzo government is in trouble. Yet comment on Abe’s disastrous Upper House election of July and on his subsequent cabinet reorganization of August, with few exceptions, ignores Okinawa, the prefecture where the burden of the reorganized US-Japan alliance is heaviest, the veneer of Abe “reformism” thinnest, popular discontent deepest, and the consequences of failure potentially most serious.

This essay, following other recent comments on Okinawan political and social developments (both in Japan Focus and in my new book, Client State: Japan in the American Embrace), addresses the Okinawan experience of Abe politics as the embattled Prime Minister moves to revamp the alliance with the US and extend nation-wide the Okinawa template of US-Japan cooperation. Although Prime Minister Abe talks of his intention to “heed” and “humbly accept” the opinions of people in Japan’s regions, the Okinawan experience suggests otherwise. Room for negotiation shrinks as Tokyo moves from negotiation and compromise to coercion.

Okinawa” Client Prefecture in a Client State

Following his crushing electoral defeat in the Upper House elections of July 2007 (in which the Liberal-Democratic Party lost control of the House for the first time), Abe Shinzo in August reshuffled his cabinet. He interpreted the rejection at the polls as a chastisement for “inappropriate remarks made by some former Cabinet members and the problems surrounding political funding and pension records,” and insisted his policies would not change. He would deliver “a fresh start on the creation of a beautiful and new country,” and continue to insist on the need to “boldly reexamine” the structures established after World War II, including the constitution. But he promised, however, to listen to the people:

“We must heed the voices of the people in local regions, humbly accept their opinions and respond to them with policies. … The members of the new Cabinet will visit the regions and lend their ear to the people.” [1]

The electorate seemed unconvinced. Support for his new cabinet did not rise from the low 30s range. Nowhere was the electoral rebuff he suffered more severe than in Okinawa. Few there expected any change of heart and most braced themselves for confrontation rather than conciliation. Before, during, and after the election, trust in the Abe administration, even on the part of the supposedly conservative local government, was at historically low ebb.

Abe’s problems included not just a fractious and unhappy electorate but also a dissatisfied and critical Washington. Just one day after the Japanese electorate rebuffed him, on 30 July, the US House of Representatives rebuked him, adopting Resolution 121 that severely criticized his stance of denial on the so-called “Comfort Women” issue. A Japanese Prime Minister who antagonizes both his own electorate and the US government cannot survive long. As I have argued elsewhere, the Japanese government rests on a contradiction, and the attempt to paper over that contradiction has become steadily more difficult under Koizumi and Abe. [2]

To put my argument in its simplest terms, the steps taken to incorporate the Japanese state as a subordinate unit under US direction contrapuntally require stress on Japanese tradition, “beautiful” country, patriotism, and denial of war responsibility; client state subordination seems the antithesis of neo-nationalist assertion but is actually its structural complement. Since he replaced Koizumi in September 2006, Abe has been torn between his desire to serve and to please Washington on the one hand and his nationalist pretensions on the other. The greater his efforts to meet American demands, the more he stresses the beauty and integrity of Japanese history and tradition and calls for a break with the American-inspired postwar system, and the more in turn that that irritates the US. The contradictions of the postwar state are not new, but in the post-Cold War context they surface in plain view like a giant iceberg. The strands of client state policy are incompatible in logic, and only the theatrical genius of a Koizumi could make them appear coherent in practice. Abe is no Koizumi.

To the extent that the government of Japan sees its primary policy imperative as submission to Washington, it has to “deliver” Okinawa to the Pentagon, and to do that it must somehow ensure the submission of Okinawa’s restive local government and civil society. But if Okinawan civil society – in effect its citizen-rooted democracy – refuses to play its assigned role, then the best laid plans of the world’s two greatest powers will founder on Okinawa’s rocks.

The Base that Cannot Be Built

For all his many political and media skills, on Okinawa Abe’s predecessor as Prime Minister, Koizumi Junichiro (Prime Minister, 2001-2006) was a failure. In October 2005, almost ten years after the Government of Japan promised to build and deliver to the US a new military complex to replace the existing obsolescent and inconvenient base at Futenma, he canceled the project, admitting defeat in the face of “a lot of opposition.” Strictly speaking the fishing village of Henoko defeated the Japanese state, forcing major rethinking about the military reorganization plan on the part of the world’s No. 1 and No. 2 powers.[3]

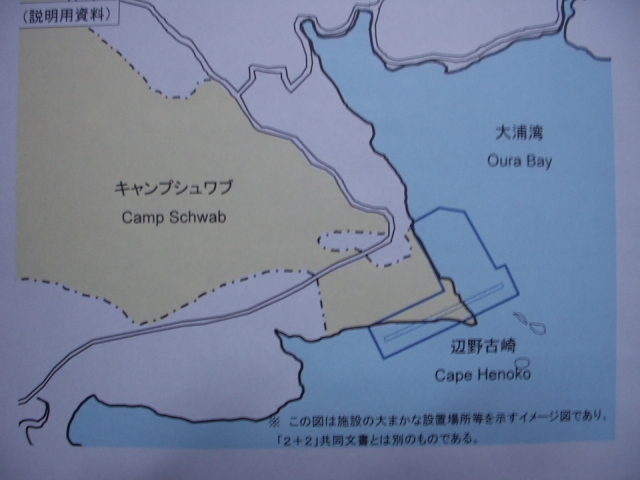

Although that plan was cancelled, a new one was quickly adopted. Instead of the originally planned “heliport” and of the later, offshore floating pontoon runway proposal, Japan promised to construct a much larger, comprehensive military complex combining land, sea, and air facilities, fulfilling a US design first formulated at the height of the Vietnam War. [4] It would expand on existing US structures at Camp Schwab on Cape Henoko (in northern Okinawa), building a “V”-shaped dual runway across the Cape, extending it at both ends by reclamation, and construct a deep-water naval port (theoretically one capable of accommodating nuclear submarines). Since construction would be undertaken based on the existing base facilities, protest access would be much more difficult. It was a plan that could only further inflame Okinawan protest.

Okinawa’s strategic location, and the concentration of marine, naval, and air force power and personnel there, have long made it a keystone of US military power in the Western Pacific. Only in Okinawa does the US military presence overwhelm local society and it is in Okinawa, therefore, that the political consequences, for Abe and for the US-Japan relationship, are potentially most serious. This new base would constitute a crucial component of the comprehensive agreement on reorganizing US forces in Japan, incorporating powerful Japanese forces under US command into the war on terror throughout the Arc of Instability. Nominally a replacement for Futenma, it would amount in fact to a significant military upgrade.

Although the Government of Japan promised in May 2006 that it would build and hand over these new facilities to the US by 2014, more than a year passed without the environmental survey of the site required by the 1997 law even commencing, since both the prefectural Governor, a conservative figure elected in 2006 with the support of the LDP and the national government, and the mayor of Nago City, resisted the deal, which had been negotiated over their heads. A decade of efforts by his predecessors to cajole, persuade, and bribe Okinawans to accept their role as host of one of the major military complexes of Asia, having failed, Abe seems to have opted for coercion. He appears ready to overwhelm any Okinawan opposition by invoking all available powers of the state. His message to Okinawa is simple: cooperate or else. Consequently, nowhere in Japan could people be more skeptical of Abe’s pledge to “heed the voices of the people in local regions, humbly accept their opinions and respond to them with policies.”

Caught between the conflicting pressures of the Pentagon and the people of Okinawa, it was hardly to be expected that Abe would pay serious attention to Okinawans. Throughout modern Japanese history Tokyo has looked down on Okinawa and sacrificed it to greater national ends. When (then) Foreign Minister Aso Taro in mid-2007 carelessly raised the possibility of Okinawa being attacked, and a counter-attack being launched from its American bases, i.e. of war returning to the islands, his words drew little attention elsewhere in Japan but were a bitter reminder to Okinawans that their “forward” role in the defense of Japan exposed them to threat today just as the presence of Imperial Japanese Army made them liable to attack and devastation in 1945. [5] What was surprising, however, was that Abe seemed to go out of his way to antagonize Okinawa. While resorting to enforcement on the base issue, he further angered Okinawans by his government’s insistence on imposing a revisionist understanding of war history. The combination raised popular anger and discontent to new heights.

Tokyo’s Persistent Denialism

On 30 March 2007, the Ministry of Education revealed that in the textbook screening process of the previous year it had ordered deletion from high school texts of all reference to Okinawans having been ordered in 1945 by the Imperial Japanese Army to kill themselves (“compulsory suicide”) rather than surrender. Abe’s “beautiful country” agenda, which required denial of responsibility for the “Comfort Women,” prompting anger and consternation from Beijing and Pyongyang to Washington and Ottawa, likewise required denial of the compulsory suicides, antagonizing Okinawans. Abe’s government seemed to be bound by some inner logic to give priority to ideological questions of denialism over practical policy considerations.

As Secretary-General of the Dietmembers Association for Reflection on the Future of Japan and History Education” from its inception in 1997, Abe had built his political career around issues of denial of war responsibility in the cases of the atrocities of Nanjing, the Comfort Women, the forced labor of Chinese and Koreans, and the Okinawan “compulsory suicides.” Okinawa lost more than one-quarter of its population and its islands were devastated in the catastrophe that swept over them in 1945, but no memory is more bitter to Okinawans than that of their forbears being ordered to kill themselves so as not to inconvenience the Imperial Japanese Army’s war.

The order from the Ministry of Education was an outrageous assault on Okinawa’s collective memory. Anger quickly spread, resolutions of protest were passed in municipal assemblies throughout the prefecture, and on 22 June the Okinawan Prefectural Assembly adopted a unanimous resolution demanding the texts be restored. On this issue, party divisions fell away, there was no opposition. The speaker of the House, himself an LDP member, spoke movingly of his own personal experience as an 8 year-old sheltering in a cave during the Battle of Okinawa, when he witnessed Japanese soldiers giving parents a poisoned rice-ball to kill a crying child.

When Okinawan delegations went to Tokyo to demand that the Ministry restore the passages deleted from the texts, no senior official would meet them. [6] They were told, in a tone that was widely reported in Okinawa to have been contemptuous, that nothing could be done. Further angry resolutions were adopted, one jointly by all 41 mayoralties and then confirmed by the prefectural assembly. With the Abe government still refusing to budge, an “All-Okinawa Mass Meeting” of citizens, from the Governor on down, including all political parties, major office holders, and civil society organizations, was scheduled for 29 September. Paid little attention outside Japan (or even elsewhere in Japan), this prefecture-wide rising was no less significant a challenge to the Japanese body politic than the Congressional reprimand.

Only once before had there been such a meeting, in October 1995, when prefecture-wide anger at the incident of rape of an Okinawan child by American servicemen threatened the fabric of Okinawa as a joint US-Japan “base island.” That meeting brought more Okinawans together than ever before or since, and it stirred the two governments to agree between themselves that the bases had to be reduced and Futenma returned. Eleven years on, that promise is nowhere in implementation. The emptiness of the 1996 promise is itself cause for Okinawan distrust.

October 22, 1995 protest march and rally

October 22, 1995 protest march and rally

From “Pre-Survey” to Survey

The Henoko base construction plan was in place before Abe took office (in September 2006), but it fell to him to implement it. Since all of Koizumi’s efforts at persuasion had failed, Abe appears to have decided that his government would get tough. [7] No Okinawan had been consulted about the agreement, which ignored the three principles on which Governor Inamine had been insisting – the base airport to be for joint military-civilian use, its military use restricted to 15 years, and assurance of no environmental damage – and likewise ignored the prefecture’s insistence on stipulation of a closure date for Futenma within three years. When the Governor and the Nago Mayor called for the plan to be revised they were given short shrift. The plan would not and could not be amended. Tokyo had no “ears” to listen to such protests.

At the end of April 2007, it initiated a “pre-survey survey” of the base site in the sea around Henoko. As Okinawa University president, Sakurai Kunitoshi, put it: “The Environmental Assessment Law requires developers to draw up a plan that lists survey methods, show it to residents and local governments and conduct the survey in a way that reflects their opinions. Conducting a survey before such steps are taken violates the law.” [8] Questioned as to legality, the Defense Facilities Agency spokesman could only say that “in principle” things should be conducted in accordance with the law, but the government had been unable to obtain the necessary consents and since time was urgent, preliminary data were being collected anyway. [9] In other words, the government had decided to sweep aside the inconvenient legal requirements.

Between 18 and 20 May, a minesweeper of the Maritime Self-Defense Forces was ordered to Henoko to assist in the operation. It amounted to a double illegality, in breach of both the Environmental Assessment Law (for the reasons given by Sakurai) and of the Self Defense Law (which had no provision authorizing dispatch of the SDF in such a domestic situation, in an essentially intimidatory role). Thus one of the very first acts of the upgraded Ministry of Defense was the deployment of “defense” forces against Japan’s own civil society.

The SDF involvement significantly raised the level of tension at the planned construction site between contractors acting under the orders of the Defense Facilities Agency (part of the Ministry of Defense) and protesters. On 21 July, three government contractors, clad in diving suits, went down some three to four meters to the seabed about one kilometer off Henoko fishing harbor, either to install or adjust passive seabed sonars (possibly to record the passage of protected dugong).[10] Four members of the opposition movement (three in diving suits, one a skin diver) quickly followed them down, and a bizarre sea-bed struggle took place. The protesters claimed later they had been kicked and beaten, efforts made to wrench their gas tanks from their backs, and eventually, the gas valve on the tank of the leading protester had been twisted shut. Fortunately, the diver, Taira Natsume, a Christian pastor long active in the protest, was able to get to the surface without blacking out.

Film later released by the protesters seemed to show the sequence of actions of which the protesters complained, but it was hard to be sure.[11] Taira himself, in his own subsequent “Emergency Statement” issued on 26 July, maintained that primary responsibility attached to the Defence Facilities Agency, which had initiated the illegal activities and placed the contractors under heavy pressure to perform, rather than on the individual contractors in the sea-bed confrontation. If it can indeed be established beyond doubt that government agents deliberately cut off Taira’s oxygen supply, that would constitute attempted murder. Suffice it to say that many in Okinawa saw it that way and anticipated more violence from the state as the confrontation continues.

In August, the Ministry of Defense served final notice on the Okinawan prefectural and municipal authorities of intention to move from this illegal preliminary survey to the survey actually required by law. Both Governor and mayor persisted in their opposition, but Tokyo simply overrode their objections, determined that the environmental impact survey would be undertaken regardless. [12] However, without Okinawan cooperation, the proclamation could not be posted in the normal, government places. Instead, in an astonishing display of Tokyo disregard for Okinawan sensibilities, it appeared only in the offices of the Defence Facilities Agency and in a few other, obscure rented spaces – a room off the lobby of a hotel, a rented apartment room. [13] A legal procedure designed to maximize public consultation was being manipulated to evade it and to compel public compliance.

By setting aside legal obstacles and constitutional principle in order to deliver the base Japan had promised to the Pentagon, Abe was showing his chosen pose of unflinching, Churchillian determination, [14] simultaneously provoking, threatening, intimidating and issuing uncompromising and unacceptable demands. In theory, a negative determination by the environmental impact survey could still frustrate him, since the militarization of northern Okinawa could scarcely be accomplished without large negative consequences for the dugong, turtle, Okinawan rail (kuina) and other denizens of those still relatively pristine waters and woodlands. But nobody expects a serious, impartial, or internationally credible, survey. With the two top governments in the world already signed off on the project, the outcome was a foregone conclusion, although an international legal contest over the rights of the dugong commenced in a San Francisco court in 2003 and was scheduled to resume on 19 September 2007.[15]

Fiscal Pressure

Accompanying the physical coercion, financial pressures also were stepped up. The attempt to soften opposition by generous budgetary allocations in the name of “development” was not confined to Okinawa but it was refined and carried to perhaps greater limits there than elsewhere. The 1999 appropriation of 100 billion yen for “Northern District Development” to be disbursed over 10 years was a thinly disguised bribe designed to secure compliance from Nago City and surrounding districts in the base construction plan, but it proved ineffective: that plan had to be scrapped in 2006. Tokyo seems to have decided that it had no alternative but to cut back on the rights of local governments to consultation, in effect to whittle back their constitutional rights (under Articles 92 to 95) to self-government itself, even though this was directly contrary to its rhetoric of decentralization and “reform.”

In due course, the Abe government passed a bill explicitly tying further disbursements to local governments to their cooperation on the bases. Under the May 2007 “Law for the Promotion of Reorganization of US Bases in Japan,” the cooperative would be rewarded, and the uncooperative punished. The power to authorize, or withhold, funds for Okinawan development thus passed into the hands of the Department of Defense. Local Okinawan officials were notified by Defense bureaucrats in Tokyo that they would be subjected to punitive budget cuts if they persisted in refusing consent to the base development plans. Then Defense Minister Koike said that she was reserving judgment on whether the necessary conditions for disbursement of the funds had been fulfilled.[16] Despite the language of consultation, Okinawans interpreted the intent as an ultimatum. The Japanese government was overruling democratic and constitutional principles in order to impose “priority to the military” (songun) policies on Okinawa.

Okinawa’s Response

Whether by the extraordinary measures of resort to force majeure over Henoko (including the dispatch of the mine-sweeper), or by the freezing of “Northern Development” funds, or by denying core elements of Okinawa’s identity and memory Abe’s government was “pouring oil” onto Okinawan resentments (as the Okinawa Times put it in an editorial).

Seizing the opportunity provided by the House of Councilors election in July to deliver their response, Okinawans massively rejected the government candidates (thus marking a significant reverse in the trend of the past decade recently analyzed by Miyagi Yasuhiro for elections to have been swayed primarily by economic considerations).[17] For the Okinawa seat, the candidate most closely identified with the anti-base and anti-militarization movement, Itokazu Keiko, defeated the governing party’s (LDP and New Komeito) Nishime Junshiro by a huge margin, 376,460 to 249,136.

In the proportional representation bloc, Yamauchi Tokushin, a much-respected figure representing the same anti-base and anti-militarization movement, was elected on the Social Democratic Party’s list. As mayor of Yomitan in the 1970s and 1980s, Yamauchi had devoted himself, successfully, to securing the return from the US military of land it occupied within the village and then turning Yomitan into a model of locally generated development, free of the military connection. Yamauchi’s first act after being elected was to proceed to Henoko to meet with the sea-front protest movement representatives and pledge his solidarity with them:

“I did not stand for election just for the purpose of being elected. That was not my goal. I stood in order to join the Henoko sit-down protest wearing my Dietman’s badge, and to struggle against the construction of a new, peace-defying base. From now on, I intend to make all necessary preparations and plunge again into the Henoko struggle.”

Abe’s rule by ultimatum thus served to revive Okinawan unity, deepen its determination, and cause the two figures most closely associated with its resistance to be elected to represent it in Tokyo. He could not have hoped more fervently for the defeat of any two candidates than Yamauchi and Itokazu, outright opponents of his government’s Okinawan policies, as well as defenders of the constitution and of Okinawan memory of war.[18] They will surely be present, their Dietmember badges prominently displayed, on the platform of the All-Okinawa protest meeting. Despite the honeyed words of humility and readiness to heed the wishes of the people quoted at the opening of this article, Abe’s newly appointed Minister of Defense, Takamura Masahiko, lost no time in saying “No” to Okinawan Governor Nakaima, telling him there could be no change to the base construction plan.[19]. Since Nakaima represented the most moderate, conservative forces of Okinawa, and was the LDP’s nominee at the time of his election, the gap between Tokyo and Okinawan society as a whole may be imagined. It seemed to be a case of “full speed ahead” on collision course.

As for the US-Japan relationship, Abe’s intent to prove himself to Washington, delivering what previous governments had tried but failed to deliver, can scarcely be doubted, but by antagonizing Okinawa beyond the level of his predecessors he may instead achieve the opposite: weakening the alliance. Having alienated Washington by his denial that the wartime so-called “comfort women” were subject to “coercion in the strict sense,” irritated it by his determination to give priority to North Korean abductions of Japanese citizens three and a half decades ago over present nuclear issues in the Beijing negotiations, and appalled it by his ineptness in attempting to push through an electoral agenda of constitutional revision in the face of public apathy, thereby making it unlikely if not impossible for at least a decade, a major failure on Okinawa would make him an utterly disastrous Prime Minister in American eyes.

Gavan McCormack is an emeritus professor of Australian National University, a coordinator of Japan Focus, and author of the recently published Client State: Japan in the American Embrace. He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on September 3, 2007.

Notes

[1] Abe Cabinet E-mail Magazine No.44 (August 30, 2007).

[2] Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, London and New York, Verso, 2007.

[3] Client State, p. 165.

[4] See Makishi Yoshikazu, “US dream come true? The new Henoko sea base and Okinawan resistance,” Japan Focus, 12 February 2007.

[5] “Aso, Kyuma-shi fuyoi hatsugen,” Okinawa Times, 6 June 2007.

[6] “Okinawa shudan jiketsu – ‘gun kanyo’ de zenkai itchi,” Asahi shimbun, 23 June 2007.

[7] See my previous paper for brief discussion, “”Fitting Okinawa into Japan the ‘beautiful country’.” Japan Focus, 30 May 2007.

[8] Kunitoshi Sakurai, “Kichi izon ga kankyo o kowasu,” Asahi shimbun, 31 May 2007, translated as “U.S. Bases bad for environment in Okinawa,” Asahi shimbun, 9 June 2007.

[9] Quoted in Makishi Yoshikazu, “Kankyo no asesuho – fuminijiru seifu no kyokosaku,” Shukan kinyobi, 15 June 2007, pp. 12-13.

[10] For a brief account, “Henoko oki chosa, sagyo chu kaichu no momiai,” Ryukyu shimpo, 22 July 2007.

[11] For a detailed account, with photographs, see “Kikko no ura nikki” .

[12] “Boeisho asesu hohosho teishutsu– chiji iken kyohi no hoshin,” Ryukyu shimpo, 8 August 2007; “Kenmin no ikari mushi suru ka,” Okinawa Times, 8 August 2007.

[13] “Kyo kara kokoku juran,” Okinawa Times, 14 August 2007.

[14] On his admiration for Churchill: Abe Shinzo, Utsukushii kuni e, Bungei shunju shinsho No. 524, 2006, p.41.

[15] The suit was launched in 2003 by six Japanese and US environmental groups arguing that the construction would damage the habitat of the internationally protected dugong. (Se David Allen and Jon R. Anderson, “Dugong take first round in suit opposing Okinawa base location,” Stars and Stripes, 6 March 2005.

[16] “Boeisho, toketsu o shisa – Hokubu shinko jigyo,” Okinawa Times, 31 July 2007; “Jimoto no hampatsu dake da,” Okinawa Times, editorial, 1 August 2007.

[17] See Miyagi Yasuhiro, “Okinawa and the paradox of public opinion: base politics and protest in Nago City, 1997-2007,” Japan Focus, 3 August 2007.

[18] A third figure, 31-year old Kawata Ryuhei, an independent, non-party representative elected for Tokyo, also identified himself with the Henoko cause and promised to visit the site as soon as possible. Kawata is known as a campaigner for human rights causes, including his own – as a victim of HIV-tainted blood transfusion when he was a ten-year old. (Tatsuya Ando, “Kawata vows to be a thorn in side of the health ministry,” Asahi shimbun, 2 August 2007.)

[19] “Futenma daitai, Takamura boeisho shusei ojizu,” Ryukyu shimpo, 1 September 2007.