The Prospect of Ending the 20th Century in East Asia

(Available in Korean here)

Gavan McCormack

On 13 February 2007, a historic deal was struck in Beijing commencing the process of the denuclearization of Korea, comprehensive regional reconciliation, ending the Korean War, and normalizing relations between North Korea and its two historic enemies, Japan and the United States. The agreement is complex, and its implications are enormous, not just for the peninsula. The following paper offers a preliminary analysis.

The “North Korea Problem”

The tectonic plates under East Asia have begun to shift. In a world where gloom predominates and resort to force to settle disputes is common, and more often than not indiscriminate, the prospect of war recedes, and a new order of peace and cooperation begins to seem possible, radiating out from the very peninsula that was throughout the 20th century one of the most violently contested and militarized spots on earth. Japanese colonialism, the division of Korea and its consequent civil and international war, the long isolation and rejection of North Korea and its confrontation with the United States and with South Korea, and the bitter hostility between it and Japan: all these things suddenly seem to be negotiable.

With the end of the Cold War, in Europe accommodation replaced confrontation and the iron curtain was raised, but in Asia, especially on the Korean peninsula, things were more difficult. A US-North Korea accommodation was negotiated under Clinton in 1994, which successfully froze North Korea’s plutonium projects in exchange for US economic aid and brought bilateral relations to the brink of normalization in 2000, only to be returned to square one with the advent of George W. Bush. His administration’s hostility, near to absolute, precipitated the collapse of the Geneva Agreed Framework, North Korea’s withdrawal from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and led, in October 2006, to its nuclear test.

From August 2003, the United States and North Korea, flanked by the regional countries – Japan, China, Russia and South Korea – have been sitting around a table in Beijing from time to time to try to solve what is commonly called the “North Korea problem.” There was, however, a fundamental difference of opinion over the nature of that problem: for the US, it was a matter of curbing North Korean nuclear weapons and ambitions. Pyongyang had to be brought to heel because, as Dick Cheney once famously said, “you do not negotiate with evil, you defeat it.” For regional countries (North Korea included) however, the nuclear issue was itself primarily symptomatic: it could not be addressed independently of the matrix of unresolved historical contradictions in which it was set. De-nuclearization and regional security were only likely to be accomplished as part of diplomatic, political and economic normalization designed to address the tragic legacies of the 20th century.

During those Beijing negotiations, the US long refused to talk to North Korea at all, or consider any form of security guarantee, or any form of phased, step-by-step, reciprocal mode of settlement. Any reference to the principles of the Clinton government’s “Agreed framework” of 1994, in particular any revisiting the question of the provision of light-water reactors to North Korea, was anathema. All it was prepared to discuss was North Korea’s unilateral submission, or CVID (complete, verifiable, irreversible dismantling of its nuclear weapons and materials). Eventually, however, after prolonged and intense pressure from the majority (China, Russia, and South Korea), the US slowly yielded, retreating from position after position as it found itself unable to impose its will and unable to rely on the support of any of its partner countries save Japan.

September 2005 – The Agreement that Failed

In Beijing on 19 September 2005 at last an agreement was reached. The US accepted the principle of a graduated, step-by-step approach to achieve full nuclear disarmament and political, diplomatic and economic normalization, and it agreed that North Korea’s entitlement to light water reactors would be considered once it rejoined the Non-Proliferation Treaty. In other words, the US abandoned all of its previous positions and came to accept the position of the Beijing majority, which in turn was actually very close to the North Korean position.

Six-party representatives, September 14, 2005

It was the United States that then had to be dragged, protesting, to the signing ceremony, only after it had exhausted all possibilities of delay and was fearful of becoming what Jack Pritchard, formerly the State Department’s top North Korea expert, described as “a minority of one … isolated from the mainstream of its four other allies and friends,” [1] and when it faced an ultimatum from the Chinese chair of the conference to sign or bear responsibility for their breakdown.[2]

Immediately after pledging “respect,” however, at the closing ceremony in Beijing the US representative, Christopher Hill, made a statement denouncing North Korean illegal activities, declaring the intention to pursue it over human rights, chemical and biological weapons and missiles, and insisting that nothing in the Agreement should be considered as an endorsement of North Korea’s “system.”[3] It was as clear a statement as one could ask for of continuing American hostility and refusal of respect. The following day, the US launched financial sanctions designed to bring the Pyongyang regime down.

In other words, at the very moment when agreement was being painfully reached in Beijing, American policy on North Korea came under the sway of those whose loathing for the regime led them to be more concerned with achieving regime change than with solving the nuclear question. Walking away from the Beijing process, the US refused all North Korean overtures for discussion, and launched a series of steps designed to “strangle North Korea financially.” [4] They were intent on literally closing it down, by delivery of a “catastrophic blow” to the very fundaments of the North Korean system.[5] Banks around the world were pressured to refuse any dealings with North Korea because of allegations that one small Macao bank, Banco Delta Asia (BDA), had been dealing in counterfeit, North Korean-made, hundred dollar notes. At issue were deposits amounting to twenty-odd million dollars, roughly the amount of money that the CEO of a US multinational would earn in a year. No evidence whatever was offered to support the US claims. South Korea’s ambassador to the Six Party Talks, Chun Youngwoo, referred to North Korea being “besieged, squeezed, strangled and cornered by hostile powers,” and noted that the talks had suffered from the “visceral aversion” and “condescension, self-righteousness or a vindictive approach” on the part of parties unnamed (by which he plainly meant the United States).[6]

US actions during this period from late 2005 would seem to have been based on a combination of something called the “Illicit Activities Initiative,” the brainchild of Vice-President Cheney (recently detailed by Japanese journalist Funabashi Yoichi),[7] and a design from Donald Rumsfeld’s Pentagon under what was known as “Operation Plan 5030” to subvert North Korea by means short of actual war, including “disrupting financial networks and sowing disinformation.”[8]

The basic details of the negotiation of the Beijing September 2005 agreement as outlined here are well known: the “North Korea problem,” differently stated, was the “US problem.” Yet so generally isolated and reviled is North Korea that one could get little sense of this from the global media. Instead, Pyongyang was almost universally blamed, both for its initial reluctance about the deal and then for refusing to honor it (when Pyongyang, facing clear US plans for its subversion, decided to demand that the light water reactors be provided as a pre-condition before it would fulfill its obligations). The International Crisis Group described the Bush administration as “[a]ttempting to squeeze North Korea into capitulation or collapse by wielding economic sanctions at the moment when negotiations were beginning to bear fruit, refusing to meet with the North outside the multilateral talks and pressing human rights concerns.”[9]

C. Kenneth Quinones, a former State Department official with considerable experience in negotiation with North Korea, said that he had been able on no less than three occasions in 2005 to find a basis for agreement between the North Korean and US governments only to have his efforts sabotaged by the Bush/Cheney/Rumsfeld leadership. He referred to North Korea as being “very precise and consistent in their positions” while by contrast the track record of the Bush administration was “not one of diplomacy but rather one of vacillation, inconsistency and, ultimately, undercutting the position and the efforts of its own diplomats.”[10] Tom Lantos, from January 2007 Chair of the House International Relations Committee, called on the administration to “resolve the feuds within its own ranks which have hobbled North Korean policy.”[11] In short, the Bush administration was torn between the advocates of regime change and of negotiated settlement, leaving its diplomacy “dysfunctional.”[12]

After its pleas for direct talks on the US allegations, and its offer to open an alternative account in a designated US bank, under appropriate surveillance,[13] were rejected, and after due warning, North Korea then carried out missile and nuclear tests in June and October 2006. Those tests are not to be defended, but their context should be understood.

North Korea’s Test and the US Elections

Some time later, and after United Nations Security Council resolutions condemning North Korea and imposing limited sanctions, the US position changed and the Bush administration agreed, for the first time, to direct talks with North Korea. These talks were held over three days in Berlin in January 2007, and a Memorandum of Agreement was signed under which North Korea would freeze its nuclear programs, stop its reactor, re-affiliate with the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and open its plants to IAEA inspectors, as the first step towards full nuclear disarmament. In return the US would, as a first step in reconciliation, provide energy and humanitarian aid and pledge to unfreeze the North Korean accounts in Macao. The US is also said to have “responded positively” to North Korea’s request for the conversion of the 1953 armistice into a peace treaty. Shortly afterwards, US Treasury officials met with officials from Pyongyang to discuss the Macao bank matter, after which it was widely reported that some proportion at least (most likely around 11 million dollars) of the frozen North Korean funds would soon be unfrozen.[14]

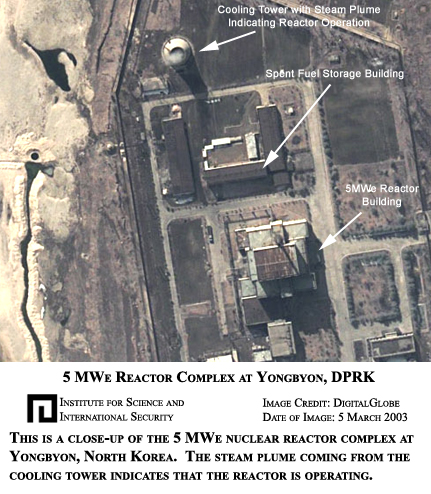

The Berlin agreement was then confirmed and fleshed out at a 6-Party meeting in Beijing on 8 to 13 February 2007. North Korea would within sixty days shut down and seal its Yongbyon reactor as a first step towards its permanent “disablement,” and bring back the IAEA inspectors. The other parties would grant it an immediate aid shipment of 50,000 tons of heavy oil and an additional 950,000 tons of oil (or cash equivalent) when at the end of the sixty days the North Koreans presented their detailed inventory of nuclear weapons and facilities to be dismantled. Talks would begin with the US and Japan aimed at normalizing their relations. The US would “begin the process” of removing the designation of North Korea as a state sponsor of terrorism and “advance the process” of terminating the application to it of the Trading with the Enemy Act. Five working groups were to be set up to address the questions of peninsula denuclearization, normalization of DPRK-US relations, normalization of DPRK-Japan relations, economy and energy cooperation, and Northeast Asian peace and security.[15] The parties pledged to “take positive steps to increase mutual trust” and the directly related parties to “negotiate a permanent peace regime on the Korean peninsula.”

The process of steering the Beijing agreement towards full nuclear disarmament and diplomatic, political, and economic normalization on the Korean peninsula will at best be prolonged and fraught with difficulty, but Washington’s readiness to start normalizing relations with North Korea, removing the terrorist label from it and easing economic and financial restrictions on doing business with it, even before completion of nuclear disarmament, were major and unexpected concessions.[16] An end to that half-century long embargo, and diplomatic and economic normalization, would certainly meet North Korea’s “precise and consistent” aims and render nuclear defenses unnecessary. However, while the general principles are clear, much remains vague about how to achieve the wider goals.

Some accounts suggest that North Korea suddenly became amenable to reason because of Security Council Resolution No 1718 and its accompanying sanctions (following North Korea’s nuclear test), or because of Chinese pressure, or severe economic conditions. But that argument seems disingenuous. North Korea had scarcely changed its position since the Beijing talks began – or indeed since it entered the Geneva Agreements with Clinton. It had always been ready for a freeze, leading to step-by-step de-nuclearization, but only as part of a process leading to security and normalization.

It was the US position that had moved 180 degrees. Not only did it abandon its hard line early stance of refusal to meet or talk to the North Koreans, but it seems to have dropped, at least temporarily, three major matters that had been the subject of bitter contention:

(1) HEU: the supposed secret North Korean highly enriched uranium-based weapons program – so important in 2002 as to have led to the collapse of the Clinton Agreed Framework and the present phase of crisis;

(2) BDA: the Macao bank counterfeit charges – so important in 2005-6 as to have been the principal cause of a twelve month-long crisis. Christopher Hill, the chief US delegate in Beijing, announced as the delegates were about to disperse that this dispute would be settled “within 30 days,” which could only mean that it had already been settled.[17]

(3) LWR: North Korea’s demand for light water reactors, a key component of the 1994 Clinton agreement always fiercely opposed by the Bush administration but of the utmost importance for North Korea, canceled by Washington at the end of 2002, when works were about 40 per cent complete, and bitterly disputed in 2005.[18].

Whether these matters had all, like the Macao Bank matter, been amicably resolved behind the scenes remained to be seen.

Christopher Hill announcing tentative agreement, Feb. 12

Bush Shocks?

How is such an apparent Washington change of heart to be understood? The fundamental factors would seem to have been the US Republican debacle in the Congressional elections of November 2006 and the continuing catastrophe of Iraq, together with the increasingly sharp focus of the Bush administration’s attention on Iran, and the likelihood that the Middle East war would be greatly expanded. It was the more important for the administration to have something to show for the long Beijing process at a time when US diplomacy elsewhere was in tatters and the Middle East erupting. It may be that the degeneration of the Middle East might also be inclining the US towards an accommodation with China over boundaries of influence in East Asia. North Korea’s October 2006 nuclear test also undoubtedly caught Washington’s attention in a way nothing else could.

One Japanese commentator offered the following perspective: Bush was returning, essentially, to the Clinton formula of 1994, with the great change that Pyongyang had become nuclear on his watch – although the word “freeze” was an anathema, and instead “dismantling” was used at every opportunity. The Bush CVID formula had morphed into something like its opposite: partial, prolonged, unverifiable (any agreement would have to rely, fundamentally, on trust, since North Korea plainly possessed substantial stocks of plutonium and might be expected to try to “salt” some away hidden from inspections against the possibility of negotiations over normalization stalling), and reversible (since the experience of producing and testing nuclear weapons could not be expunged), and the Bush solution for Northeast Asia involved greater reliance on China (restoring a kind of “tribute system”). For the first time, there was a real prospect of peace treaties (US-North Korea, Japan-North Korea) and normalization on all sides. US Forces would serve no further function in South Korea and Japan under such an order and might in due course be withdrawn (or sent to the Middle East). Parliamentarians in Seoul were said to be talking of a South-North Korea summit in August 2006, possibly to be followed by a grand 4-sided (Two Koreas, China and the US) conference to establish a new peninsula order.[19]

The Nixon Shocks of 1970 would pale by comparison with such “Bush Shocks.” South Korea and Japan face especially large consequences. For Japan, dependence on the US has been the almost unquestioned foundation of national policy for over half a century. A new level of subjection to US regional and global purpose, presupposing an ongoing North Korean threat, has just been negotiated.[20] The prospect of anything like the above shift in US Asian policy would be devastating to Tokyo. It can hardly have been coincidental that previously unimaginable rumbles of criticism of the Bush administration began to be heard from Tokyo, from the Minister of Defense and Minister of Foreign Affairs no less, over Iraq, a “mistaken” war whose justification had not existed and which had been pursued in “childish” manner, and over Okinawa, where the US was too “high-handed”. Neither earned more than the mildest of rebukes from the Prime Minister.[21] When the Beijing deal was struck, Japan was notably the odd-man out. Both Abe and his chief negotiator in Beijing, Sasae Kenichiro, protested that Japan could not be party to any aid to North Korea until the abduction issue was settled, so the financial tabs would be picked up by the US, China, and South Korea (Russia was assisting North Korea independently by agreeing to cancel 90 per cent of its debt, estimated to be in the range of 8 billion dollars).[22]

Prime Minister Abe Shinzo owed his rise to political power in Japan in large part to his ability to concentrate national anti-North Korea sentiment over the issue of abductions of Japanese citizens in the late 1970s and early 1980s. If the North Korean nuclear issue is now to be resolved, Japan faces the possibility of a reversal in US policy as relations are normalized with North Korea and China assumes significantly greater weight in American thinking. Japan found itself isolated at Beijing precisely because it had allowed domestic political considerations to prevail over international ones in framing the North Korean abductions of 1977 to 1982 as a unique North Korean crime against Japan rather than as a universal one of human rights (since in such a frame Japan itself would become the greatest 20th century perpetrator, and Koreans, north and south, among the greatest victims).[23]

In Seoul too, specialists on South-North relations and major think tanks expressed alarm that, after so long determinedly standing in the way of any solution to the underlying peninsula problems, the US now might be moving too fast. In the longer term, a united, de-nuclearized and substantially demilitarized Korea, rich in resources and high levels of education, at the center of the world’s most dynamic economic region, could be expected to play an ever more prominent role, perhaps the core role in the construction of the Northeast Asian Community that might, in due course, grow out of the Beijing-Six grouping, but in the short term the risk of suddenly destabilizing the historic logjam of North Korea could be considerable, especially if, for example, the UN command were to be dissolved and US forces drastically or totally withdrawn in the process of normalizing relations with North Korea before the process of de-nuclearization was complete.[24]

As for North Korea, having stood firm in the face of denunciation, abuse and threat, having pressed ahead with missile and nuclear tests and ignored the UN Security Council’s two unanimous resolutions of condemnation and its ensuing sanctions, in other words having stuck to its guns, both metaphorically and literally, it seemed to be on the brink of accomplishing its long term “precise and consistent” objectives — security, an end to sanctions, and normalization of relations with both the US and Japan. It was something for its leader, Kim Jong Il, to relish on the eve of his 65th birthday (16 February). It would certainly not be easy for North Korea to give up the nuclear card, which it had already celebrated publicly as a historic event and guarantee of security, but the point of the Berlin and Beijing agreements was to construct a framework of trust and cooperation in which other “assurances” of security would became unnecessary. That would be a long-term process, but it was beginning.

Repercussions

American neo-conservatives were furious at their government’s apparent reversal. Dan Blumenthal and Aaron Friedberg wrote that the talks were “a step in the wrong direction,” rewarding “the world’s worst regime” for its bad behavior. They argued that the pressure should be stepped up, North Korean ships and aircraft subject to “aggressive interdiction,” and pressure applied to China to compel its cooperation.[25] For Nicholas Eberstadt, “the Bush Administration’s North Korean climb-down has been almost dizzying to watch … [it] was proffering a zero-penalty return to the previous nuclear deals Pyongyang had flagrantly broken – but with additional new goodies, and a provisional free pass for any nukes produced since 2002, as sweeteners.”[26] When the deal was done, former UN ambassador, John Bolton, denounced it as “a very bad deal,” making the Bush administration “look very weak.”[27]

It is true that in the short-term Kim Jong Il stood to be “rewarded” by the kind of settlement underway, but the fact is that the greatest beneficiaries are likely to be the long-suffering people of North Korea. War, periodically considered by the US, would have brought unimaginable disaster, not only to the people of North Korea but to the entire region. “Pressure and sanctions,” as South Korea’s former Unification Minister recently commented, “tend to reinforce the regime rather than weaken it.”[28] Normalization, on the other hand, will require the leaders of North Korea’s “guerrilla state,”[29] whose legitimacy has long been rooted in their ability to hold powerful and threatening enemies at bay, to respond to the demands of their people for improved living conditions and greater freedoms. Songun (primacy to the military) policies have thrived on confrontation and tension. As the diplomatic and security environment is normalized they will have to give way to sonmin (primacy to the civilian) policies. A completely different kind of legitimation will be necessary.

If there is a North Korean “lesson” in this, however, it might be the somewhat paradoxical one that it pays to have nuclear weapons and negotiate from a position of strength (unlike Saddam Hussein, or the present leadership of Iran), and that it helps to have no oil (at least no significant and verified deposits), no quarrel with Israel, few Arabs or Muslims, and no involvement (despite the rhetorical excesses of the Bush administration) in any “axis of evil.” Undoubtedly it pays too to have neighbors like North Korea’s, who have recognized the regional costs of war and ruled out any resort to force against it.

The test for both North Korea and the US comes in the months ahead: can they begin quickly enough to build trust in sufficient measure to outweigh the accumulated half-century of hostility? Pyongyang’s next step has to be to prepare and submit the inventory of its nuclear weapons, materials, and facilities. Kim Jong Il will have to deploy all his power and prestige to enforce such a commitment – if that is indeed his intention. Conservatives will undoubtedly resist and seek to avoid meeting such obligation. For the US, the test will be no less: the neoconservative base of the Bush regime will resist meeting US obligations, lifting the terrorist label, ending sanctions, winding up the Macao bank inquiries, “trusting” and relating normally to a regime it has hated passionately.

The Beijing parties have opened the way towards a new, multi-polar and post-US hegemonic order in Northeast Asia. The 6-Party conference format might in due course become institutionalized as a body for addressing common problems of security, environment, food and energy, etc, the precursor of a future regional community. It is hard to imagine any event with greater capacity to transform the regional and global system than the peaceful settlement of the many problems rooted in and around North Korea. The Beijing February 2007 agreement may only be a first step, but its implications are huge.

[1] Charles L. (Jack) Pritchard, “Six Party Talks Update: False Start or a Case for Optimism,” Conference on “The Changing Korean Peninsula and the Future of East Asia,” sponsored by the Brookings Institution and Joongang Ilbo, 1 December 2005.

[2] Funabashi Yoichi, Za peninshura kueschon, Asahi shimbunsha, 2006, pp. 610. See also Joseph Kahn and David E. Sanger, “U.S.-Korean deal on arms leaves key points open,” New York Times, 20 September 2005.

[3] Funabashi, p. 616.

[4] Philippe Pons, “Les Etats-Unis tentent d’asphyxier financierement le regime de Pyongyang,” Le Monde, 26 April 2006.

[5] David Asher, senior adviser on North Korea matters to the Bush administration, interviewed in Takase Hitoshi, “Kin Shojitsu o furueagareseta otoko,” Bungei shunju, October 2006, pp. 214-221, at p. 216.

[6] “The North Korean nuclear issue,” Speech delivered to Hankyoreh Foundation conference, Pusan, 25 November 2006.

[7] Funabashi Yoichi, “Chosen hanto dai niji kiki no butaiura,” Asahi shimbun, 21 October 2006; Za peninshura kueschon, pp. 545, 648.

[8] Bruce B. Auster and Kevin Whitelaw, “Upping the Ante for Kim Jong Il: Pentagon Plan 5030, a New Blueprint for Facing Down North Korea,” U.S. News and World Report, 21 July 2003.

[9] International Crisis Group, Policy Briefing, Asia Briefing No. 52, 9 August 2006.

[10] C. Kenneth Quinones, “The United States and North Korea: Observations of an Intermediary,” lecture to US-Korea Institute at SAIS, Johns Hopkins University, 2 November 2006, audio link here.

[11] Quoted in Selig Harrison, “A humbled administration rethinks North Korea and Iraq,” The Hankyoreh, 28 November 2006.

[12] Selig Harrison’s word: “Pyongyang’s nuclear future and the choice of Washington and Seoul,” The Hankyoreh, 5 February 2007.

[13] “Yukizumaru 6-sha kyogi,” Sekai, May 2006, pp. 258-265, at p. 259.

[14] “Kita Chosen koza ‘sen hyaku man en toketsu kaijo mo,’ Bei ga Nikkan ni,” Asahi shimbun, 12 February 2007.

[15] “Initial Actions for the Implementation of the Joint Statement,” Joint Statement from the Third Session of the Fifth Round of the Six-Party Talks, 13 February 2007. Nautilus Institute, Special Report, 13 February 2007.

[16] Demetri Sevastopulo, “US signals flexibility on N. Korea,” Financial Times, 6 February 2007.

[17] Edward Cody, “N. Korea agrees to nuclear disarmament,” The Washington Post, 13 February 2007.

[18] Nobuyoshi Sakajiri, “N. Korea seeks massive aid for nuclear deal,” Asahi shimbun, 5 February 2007.

[19] Tanaka Sakai, “Chosen hanto o hi-Beika suru Amerika,” Tanakanews, 6 February 2007.

[20] This matter is addressed in detail in my forthcoming Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, London, Verso, 2007.

[21] For a brief account, “Criticism of Iraq war,” editorial, Asahi shimbun, 8 February 2007.

[22] “Rokkakoku kyogi: Kankoku no futan wa saidai de 935 oku en,” Chosun ilbo, 13 February 2007.

[23] For detailed analysis: Gavan McCormack and Wada Haruki, “Forever stepping back: the strange record of 15 years of negotiation between Japan and North Korea,” in John Feffer, ed, The Future of US-Korean Relations: The imbalance of power, London and New York, Routledge, 2006, pp. 81-100.

[24] Tanaka Sakai, op. cit.

[25] Dan Blumenthal and Aaron Friedberg, “Not too Late to Curb Dear Leader – The road to Pyongyang runs through Beijing,” The Weekly Standard, 12 February 2007,

[26] Nicholas Eberstadt, “Kim Jong Il’s nuclear ambitions,” Nautilus Institute, Policy Forum Online 07-010A, 7 February 2007, .

[27] Jim Yardley and David E. Sanger, “In shift, accord on North Korea seems to be set,” New York Times, 13 February 2007.

[28] “Kim Jong Il and the prospects for Korean unification,” US-Korea Institute, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University, 28 November 2006.

[29] Japanese historian Wada Haruki’s term, in his various writings on the modern history of North Korea.

Gavan McCormack is a coordinator at Japan Focus and author of various articles there, as well as a text – Target North Korea: Pushing North Korea to the Brink of Nuclear Catastrophe, (New York, 2004, translated into Japanese in 2004 and Korean in 2006). His new book, Client State: Japan in the American Embrace, will be published shortly from Verso Books. He is an emeritus professor at Australian National University.

Find other recent McCormack assessments of Korea-related issues here, here.

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted February 14, 2007.