Aso Mining’s Indelible Past: Prime Minister Aso Should Seek Reconciliation With Former POWs

Fujita Yukihisa

Translated by William Underwood

Late August 1945 photo of 57 recently liberated Australian POWs who were forced to work at the Aso Yoshikuma coal mine. Arthur Gigger is seated in the second row, fifth from left, wearing a small cap with his head slightly turned. [Courtesy of Tony Griffith, son of Arthur Griffith (front row, far left), who died in 1988.]

The POW issue as a pillar of Japan’s postwar diplomacy

The prisoner of war (POW) issue is one of the major pillars of Japan’s postwar diplomacy. Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration, which stipulated in Annex II (b) (10) that “stern justice shall be meted out to all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners.” In addition, it was Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru, the grandfather of Prime Minister Aso Taro, who signed the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Article 16 of the treaty required Japan to join the Geneva Convention that codified the treatment of prisoners of war.

It is extremely regrettable that the POW issue, the cornerstone of postwar Japan’s reentry into the international community and an important diplomatic matter, has remained to this day like a thorn caught in the throat, as no meaningful reconciliation is being achieved with aging former POWs.

In January of this year, Prime Minister Aso acknowledged in the Diet for the first time that Aso Mining used 300 Allied POWs during World War Two. Prime Minister Aso is the concerned party to this issue in a dual way: he was once president of the Aso Group and is now prime minister representing the government of Japan, which provided the company with those POWs. It is very significant that Prime Minister Aso acknowledged the fact that he had refused to acknowledge in the previous 64 years. At the same time, because this concerned party is now prime minister, I call upon Prime Minister Aso to make a major policy change by abandoning the government’s long-held policy of “omission” and removing the “thorn” from Japanese diplomacy.

Prime Minister Aso denied the fact as CEO, foreign minister and prime minister

Although Prime Minister Aso denied the existence of Allied POWs (at Aso Mining) until the end of last year, there were many instances where specific information about this reality was presented.

For a description of Western media attention to wartime forced labor by Allied POWs and Korean workers at Aso Mining, beginning right after Mr. Aso became foreign minister, please see next month’s article by Mr. Fukubayashi (in the June 2009 issue of SEKAI).

In Australia, former POWs who worked at Aso Mining began to appear in major media outlets. Nine former POWs were interviewed in June and July 2006, with the testimonies of four of these men appearing in media such as the nationally run Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and The Australian newspaper.

The Foreign Ministry, in its February 27 written response to my written question, stated that the Japanese Embassy and Consulate General in Australia did inform the Ministry in Tokyo of these news stories by official cable. But Prime Minster Aso, who was foreign minister at that time, answered my question during the House of Councillors’ Budget Committee meeting on March 9 by saying, “I have absolutely no recollection of receiving such a report.”

Prime Minister Aso telling the Diet he knew nothing about POWs at an Aso family coal mine until December 2008 (Tokyo Broadcasting System, March 9, 2009)

In June 2006, moreover, British journalist Christopher Reed introduced in his article for Japan Focus a letter written by Ms. Marilyn Caruana, the daughter of former POW Mr. John Hall, appealing to Foreign Minister Aso’s “honor and decency.”

Regarding this letter, however, the Foreign Ministry stated in its February 19 written answer to my written question, “It has not been confirmed that then-Foreign Minister Aso received it.”

Furthermore, when reporter Norimitsu Onishi wrote in the International Herald Tribune on November 11, 2006, that “Aso Mining used Asian and Western forced laborers,” the Japanese Consulate General in New York posted a rebuttal on its website. “Our government has not received any information the company has used forced laborers,” stated the rebuttal, declaring the newspaper article “unreasonable.” It was Foreign Minister Aso himself who ordered, via official cable, the posting of the website rebuttal.

However, the Foreign Ministry deleted the posting from the website last December 17, immediately after Aso Mining’s use of POW labor became clear with the discovery of relevant information in the basement of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, which resulted from my Diet questioning. During the House of Councillors’ Budget Committee meeting on March 9, I said that the Foreign Ministry must have had some grounds for the foreign minister himself to have challenged the article as not being backed by any evidence. Prime Minister Aso responded to me by admitting:

I think it was decided after confirming the relevant facts among the Ministry’s divisions and bureaus and which division should respond. At that time it was not known to us that the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare kept this kind of information. The response at that time was not necessarily adequate as a response by the government as a whole.

|

In June 2007, Professor Masaki Yoshiyuki of Daiichi Hoiku University handed a secretary at Foreign Minister Aso’s Iizuka district office a copy of the “Aso Mining Company Report,” which was submitted by Aso Mining’s Yoshikuma coalmine to the Japanese government’s Prisoner of War Information Bureau on January 24, 1946. A week later, Mr. William Underwood, a lecturer at Kurume Kogyo University, sent a letter and the same “Aso Mining Company Report” to Foreign Minister Aso’s office in the Diet building in Tokyo. This mailing also included “Report 174” about Allied POW Fukuoka Camp 26 at the Aso Yoshikuma mine, which was compiled by the GHQ Legal Investigation Section on February 1, 1946. Mr. Underwood spoke with a secretary at the Aso office in the Diet building twice by telephone, but has never received any reply about the authenticity of those records.

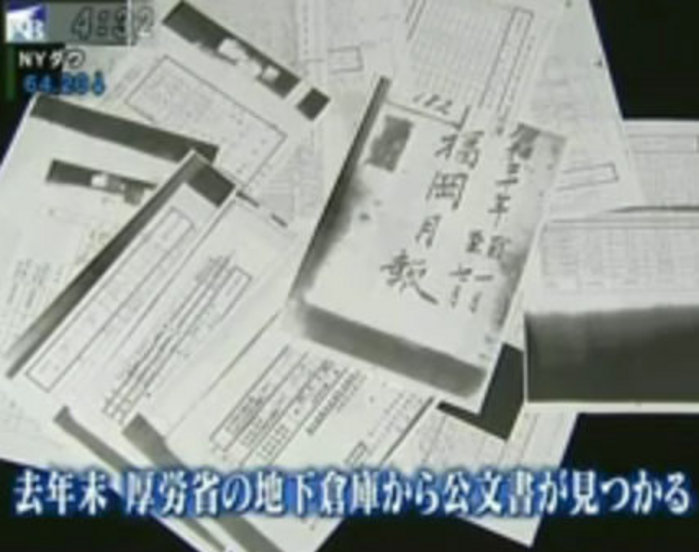

Wartime records discovered in the basement of Japan’s Health Ministry late last year (TBS)

During the Budget Committee meeting on March 9, Prime Minister Aso insisted that “I have absolutely no recollection of receiving these records,” but he finally acknowledged the less-than-adequate handling of this matter. He stated, “Our office made inquiries among those who used to work for the old Aso Mining, but could not find related information. This was the matter reported by American media the previous year and it should have been reported to me also.”

Until the end of last year, Prime Minister Aso completely denied the existence of the POWs themselves by employing rhetoric such as, “I was five years old when the war ended and have no recollection of those times.” He said at a press conference right before assuming the office of prime minister last September and in his answer to my question during the House of Councillors’ Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee meeting on November 13, “I was four or five years old at that time and had absolutely no knowledge about that fact.”

POWs missing from The 100-Year History of Aso published by Mr. Aso

The 100-Year History of Aso was published in 1975 by Aso Taro, who was president and CEO of Aso Cement Co. (presently Aso Co.) and the book’s publisher and editor-in-chief. The 1,500-page book contains detailed accounts of the glorious story of the Aso family and its business empire. Among its editors were men with wartime connections to the Aso Yoshikuma coalmine. Inexplicably, however, there is no mention at all of the POWs or the POW camp at Aso Mining, even though there is a passage stating, “POW camps were set up one after another at mines such as Furukawa Omine, Nittetsu Futase, Mitsui Yamano and Kaizuka Onoura,” as well as references to Korean workers.

On this point, Prime Minister Aso answered during the March 9 Budget Committee meeting that, because he became company president the year the book was published, he was not involved in the editorial process and has no idea about the situation at that time. But Mr. Aso became president of the company in May 1973 and The 100-Year History of Aso was published in April 1975. He had been president for nearly two years when he oversaw this company project. If his excuse were to be accepted, he may as well say, “Since I have just become prime minister I have no idea about this year’s budget or the content of bills.” Furthermore, since he says (in reference to the Aso POWs), “I was five years old at that time so I don’t know the facts,” he might as well say, “Prewar events that took place before I was born or things in foreign countries that I cannot see for myself do not concern me as prime minister.” Such behavior by a leader who represents a country is obviously unacceptable.

Villagers knew the existence of the POWs

In early March, I visited Keisen-machi in Fukuoka Prefecture, where the Aso Yoshikuma coalmine was located. I was able to meet five local residents who either had met or had some exchange with the POWs during or after the war. These local residents were children at the time and are now in their late 70s. They gave detailed accounts while taking me to the former POW camp site and showing me a map of the POW camp.

I was told about experiences such as the following: “A group of POWs passed by my house on their way to cultivation work, sandwiched between soldiers in front and back.” “Several POWs carrying big containers came to fetch water.” “After the war, they came with their relief goods such as chocolate and chewing gum that were dropped from Allied cargo planes, to barter for things like our chickens and eggs.” “They were all gaunt and wearing shorts.” Naturally, the villagers knew the prisoners were there.

Joe Coombs pointing to himself in the group photo of newly liberated Aso POWs (TBS)

The more I listened to such stories told at the actual location, the more I realized that it was impossible for Prime Minister Aso, the Foreign Ministry, and people connected with the Aso Group not to have known about the existence of the POWs. Were they forced into their continuous denials because they already knew about the POWs due to the previously mentioned media reports, records presented by researchers, and testimonies of the prisoners themselves?

Indeed, the survivors among the “300 POWs who were erased by Aso Mining for 64 years” were appearing before us like phantoms.

Segment on POWs at Aso Mining from Tokyo Broadcasting System’s News Bird television program, March 9, 2009 (source of images used in this article)

As the president who compiled the 100-year history of the company that used POWs, as the foreign minister when the existence of the surviving POWs became clear in 2006, and as the prime minister representing the Japanese Government that sent the POWs to the coal mine – Should not Prime Minister Aso, at each of these junctures, have admitted the reality of the POWs and responded appropriately?

The Japanese government finally was cornered into having to officially investigate the fact of POW labor that Aso Mining had kept sealed last November 13, when I submitted the “Aso Mining Company Report” to the Diet during a meeting of the House of Councillors’ Committee on Defense and Foreign Affairs. Forty-three pages of records were presented to me by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) on December 16, 2008. I was told that these documents from the POW Information Bureau were taken over by the First Demobilization Ministry and transferred to the custody of the Welfare Ministry (currently the MHLW) in 1956, and then never taken out until last year. I asked how this could have happened and received the following answer: “It was because matters requiring investigation were never brought up.”

This means that POW issues have never been properly discussed in a political context during the 53 years since the MHLW took charge of the materials. I trembled when I saw the records that were revealed and thought, “God has not abandoned those 300 POWs.” This was because among the source records that survived document burning, for some reason only the 1945 issues of the “Fukuoka Monthly Reports” were found. It was from May to August 1945 that the Allied POWs were used by Aso Mining. Had the records for those months not been discovered, it is highly possible that the 300 POWs would have been consigned to oblivion by Prime Minister Aso and the Japanese government.

My conversations with the surviving POWs in Australia

I had the pleasure of speaking with three surviving Australian POWs by telephone on January 18, 2009. Some family members gladly assisted my dialogue with their fathers, who are around 90 years old and not in good health. The three men recalled their experiences for me.

Mr. John Hall (born in 1919):

“At the POW camp, we were given 1.5 cups of rice and uncooked green vegetables per day, and forced to work for twelve hours. In the Yoshikuma coalmine, we had to go down very deep, where we dug coal. We worked at the third level. The air was very filthy and full of coal dust. The posts of the mine were very old and fragile, so we had falls all the time and it was very dangerous. When we had to push heavy trolleys full of coal, we were hit whenever the trolley got off the rail.”

Mr. Arthur Gigger (born in 1920):

“Treatment was not bad, but we didn’t have enough food and clothing. We were working in rags. It seemed it was a newly built accommodation, and very good. I don’t want anything from the Japanese government, but I want them to acknowledge we were slave laborers.”

Mr. Joe Coombs (born in 1920):

“We had several falls at the coal mine. Some of them were quite big, but fortunately no one was seriously injured. The camp itself consisted of new buildings. But the situation in the mine was terrible. It took us half an hour to walk down for around one mile from the entrance to the coal face. We worked in two shifts for twelve hours a day. I was around 80 kilograms but towards the end of the war my weight was down to around 48 kilograms. I’m ready to receive any kind of compensation from the Japanese government.”

Published by Aso Taro in 1975, The 100-Year History of Aso does not mention the company’s POW workforce (TBS)

Three requests from former POWs to Prime Minister Aso

These three former POWs, who at around 90 years old are facing the final phase of their lives, wrote letters to Prime Minister Aso in early February. They requested that the prime minister do three things:

1) Apologize for the inhumane treatment I suffered and the forced labor I performed;

2) Apologize for neglecting the historical truth about us POWs for the past 64 years until now;

3) Pay monetary compensation in line with global norms for redressing historical injustices.

That these men are not asking for direct individual compensation for their forced labor or so-called work makes me appreciate their deep consideration, and therefore the importance of their request. I have come to know the current circumstances of these elderly survivors. It reminds me of the cases where the lost pension records of elderly Japanese were recovered and their pension amounts were finally determined, but only after the retirees had died without receiving the belated payments. There is not much time left. There is information that nine former POWs were still living as of 2006, but only four or five are alive today. My intention has never been to blame Prime Minister Aso for the old misdeeds of Aso Mining. Negligence and concealment, however, could not be permitted. It is possible to verify and make amends.

This is the United Nations “Year of International Reconciliation.” As I pleaded during a meeting of the Budget Committee, “By all means, I would like the prime minister to invite to Japan the three or four of these men who are able to travel. Please communicate with them for reconciliation. It is the UN Year of Reconciliation. I strongly request that decisive actions be taken.” Prime Minister Aso replied, “It is possible that I could have the Foreign Ministry consider this as part of its work. Naturally, though, I could not do that arbitrarily just because I was at Aso Mining.”

I am not calling for arbitrary action. Because Prime Minister Aso is the person involved, such specific actions would produce symbolic impact. What the former POWs desire most, moreso than money, is Mr. Aso’s words. To begin with, I would like him to respond with sincere words to their first and second requests. Proactive efforts concerning hughn right issues, including the POW issue, can greatly enhance the international community’s trust in Japan. This is clear from the vigorous reporting by leading Western media even of the acknowledgment of Aso Mining’s use of POWs that Prime Minister Aso has already made.

Other remaining issues involving Aso-related companies should be resolved. Japanese and Korean media reported that, during the Japan-South Korea regular conference on the human remains issue held in Seoul in November 2005, South Korean officials requested information about the remains of the Korean laborers who worked at Aso Mining. A children’s park that I visited in Keisen-machi in March was once part of Aso Mining’s property, and many Korean remains were unearthed there during the course of redevelopment work by the company. Records of Diet proceedings show that then-Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro gave instructions for cooperation regarding the excavation of these remains and the holding of memorial services. Records of the Special Higher Police of the former Home Ministry indicate there were 7,996 Korean-born laborers at Aso Mining. I definitely want the prime minister to pursue “reconciliation of the heart” with these workers and their families.

Diet member Fujita Yukihisa, who is pressing Prime Minister Aso and the Japanese government to reconcile with wartime forced laborers (TBS)

Since 2005, Chief Cabinet Secretaries Fukuda and Hosoda have replied at the Diet that the cabinet secretariat would carry out general policy adjustments for issues of postwar settlement. Regarding the current POW issue, however, it is now clear that no governmental adjustment function exists and the Foreign Ministry, which is charged with attending to international affairs, has no constant main bureau. The lack of appropriate maintenance of diplomatic documents for the period lasting from wartime until the San Francisco Peace Treaty also has become evident. Prompt improvement on the part of the Japanese government is required.

DPJ Secretary General Hatoyama Yukio questioning Prime Minister Aso in the Diet on January 6, 2009 (English transcript available at end of Michael Bazyler article referenced below)

A moving wartime episode was recently reported, wherein a Japanese Navy captain rescued more than 400 British soldiers whose ship had been sunk by the Japanese Navy and who were floating in the sea off Indonesia. But it was also confirmed that at least one of those British soldiers became a prisoner used for labor at Aso Mining. I was able to verify this matter at the Diet due to the gift of cooperation from academics and citizens, both in Japan and abroad, who have patiently researched Allied POW issues for many years. I want to accelerate activities aimed at changing the policies of the Japanese government, in order to restore the “life and dignity of the POWs who were erased” and increase trust toward Japan within international society.

The above article, part one of two-part series, appeared in the May 2009 issue of SEKAI. Fujita Yukihisa, a member of the Japan House of Councillors, is shadow vice-minister of defense for the Democratic Party of Japan. Arimitsu Ken is executive director of the Network for Redress of WWII Victims by Japan (Sengo Hosho Nettowaku).

This article was translated by William Underwood, a Japan Focus coordinator and researcher on wartime forced labor.

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal on April 19, 2009.

Recommended citation: Fujita Yukihisa, “Aso Mining’s Indelible Past: Prime Minister Aso Should Seek Reconciliation With Former POWs,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 16-4-09, April 19, 2009.

Related Asia-Pacific Journal articles:

Michael Bazyler, Japan Should Follow the International Trend and Face Its History of World War II Forced Labor

Lawrence Repeta, Aso Revelations on Wartime POW Labor Highlight the Need for a Real National Archive in Japan

David Palmer, Korean Hibakusha, Japan’s Supreme Court and the International Community: Can the U.S. and Japan Confront Forced Labor and Atomic Bombing?

Lukasz Zablonski and Philip Seaton, The Hokkaido Summit as a Springboard for Grassroots Initiatives: The “Peace, Reconciliation and Civil Society” Symposium

Christopher Reed, Family Skeletons: Japan’s Foreign Minister and Forced Labor by Koreans and Allied POWs

Kinue Tokudome, The Bataan Death March and the 66-Year Struggle for Justice

Kinue Tokudome, Troubling Legacy: World War II Forced Labor by American POWs of the Japanese

Norimitsu Onishi, An Unyielding Demand for Justice: Wartime Chinese Laborers Sue Japan for Compensation

Matsubara Hiroshi and William Underwood, Japan Foreign Minister’s Visit to POW Remembrance Service Backfires

William Underwood, The Aso Mining Company in World War II: History and Japan’s Would-Be Premier

William Underwood, NHK’s Finest Hour: Japan’s Official Record of Chinese Forced Labor

William Underwood, New Era for Japan-Korea History Issues: Forced Labor Redress Efforts Begin to Bear Fruit

William Underwood, Proof of POW Forced Labor for Japan’s Foreign Minister: The Aso Mines

Other YouTube clips concerning Aso Mining